10 Reasons to Pay Attention to ACA Open Enrollment in 2020

The coronavirus pandemic has dominated the nation’s attention for about nine months, recently rivaled only by the Presidential election. But, there’s another thing many people may want to pay attention to right now, especially with historic job losses: How to maintain health insurance coverage at a time they may need it most.

The combination of extraordinary job losses and a historic pandemic are likely to test the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health insurance safety nets in a way not yet seen since the law’s passage. On one hand, people losing job-based coverage now may be more motivated than before to access ACA insurance programs like expanded Medicaid and Marketplace subsidies because of the pandemic. On the other hand, awareness of these key ACA programs has fallen over time, and people losing job-based coverage now may never have had a need to learn about the ACA’s programs since the 2014 implementation.

Whether new to the market or reenrolling, everyone who wants 2021 coverage through the ACA Marketplace must sign up during Open Enrollment, which takes place November 1 – December 15 in most states. In ten state-run marketplaces, the Open Enrollment period will be longer.

Here, we detail ten ways in which the 2021 ACA open enrollment period differs from enrollment periods in past years. We also provide links to a number of KFF resources for more information.

1. More people than ever before may need to know about coverage options through the Marketplace or Medicaid Expansion. Ten years ago, the ACA passed in the wake of the last financial crisis to hit the United States, when job losses left millions without access to insurance coverage. While most people in the U.S. still rely on employer coverage, the ACA creates and expands programs (specifically, the Marketplaces and Medicaid Expansion), through which people without job-based benefits can access health coverage with financial help. Since these programs went into effect in 2014, though, the economy has been relatively strong until early 2020. As such, this year’s Open Enrollment period could be the first real test of how well the ACA works to maintain coverage when large numbers lose their job-based health insurance.

Heading into 2021, continued widespread economic dislocation during this COVID-19 emergency could mean millions of people may need Medicaid or private health insurance through the Marketplace who haven’t needed that before. There are few, if any, reliable real-time data sources that would allow us to know exactly how many of the people losing employment have also lost health insurance. In an analysis of insurer-reported enrollment through June, we found employer group enrollment had dropped by 1.3%, indicating that many employers had kept furloughed workers on coverage at least temporarily. However, as more job losses become permanent, more coverage loss is possible, even likely. KFF has estimated that as many as 85% of people who are at risk of becoming uninsured due to loss of job-based coverage could be eligible for Medicaid or subsidized marketplace coverage.

2. Consumer awareness of ACA coverage options is limited. Although the vast majority of people at risk of losing coverage may be eligible for help, KFF polling finds that public awareness about ACA coverage options has fallen somewhat since the law passed a decade ago. For example, 59% of the public knows the ACA offers subsidies for marketplace health plans, compared to 75% ten years ago. Among uninsured consumers today, understanding of ACA options and enrollment rules is more limited. Less than half (43%) know Open Enrollment is the time to sign up for Marketplace plans; and 14% of uninsured individuals living in states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility under the ACA know about this expansion. KFF also finds many consumers are unsure about the current status of the ACA; as of this spring, just 22% of the uninsured know the law remains in effect. Uncertainty may result in part due to public debate and news coverage about a pending Supreme Court case to overturn the law.

The Trump Administration has reduced funding for Open Enrollment marketing and outreach by 90 percent. In this environment, news coverage of Open Enrollment and the availability of financial assistance could have an even more significant impact on public education.

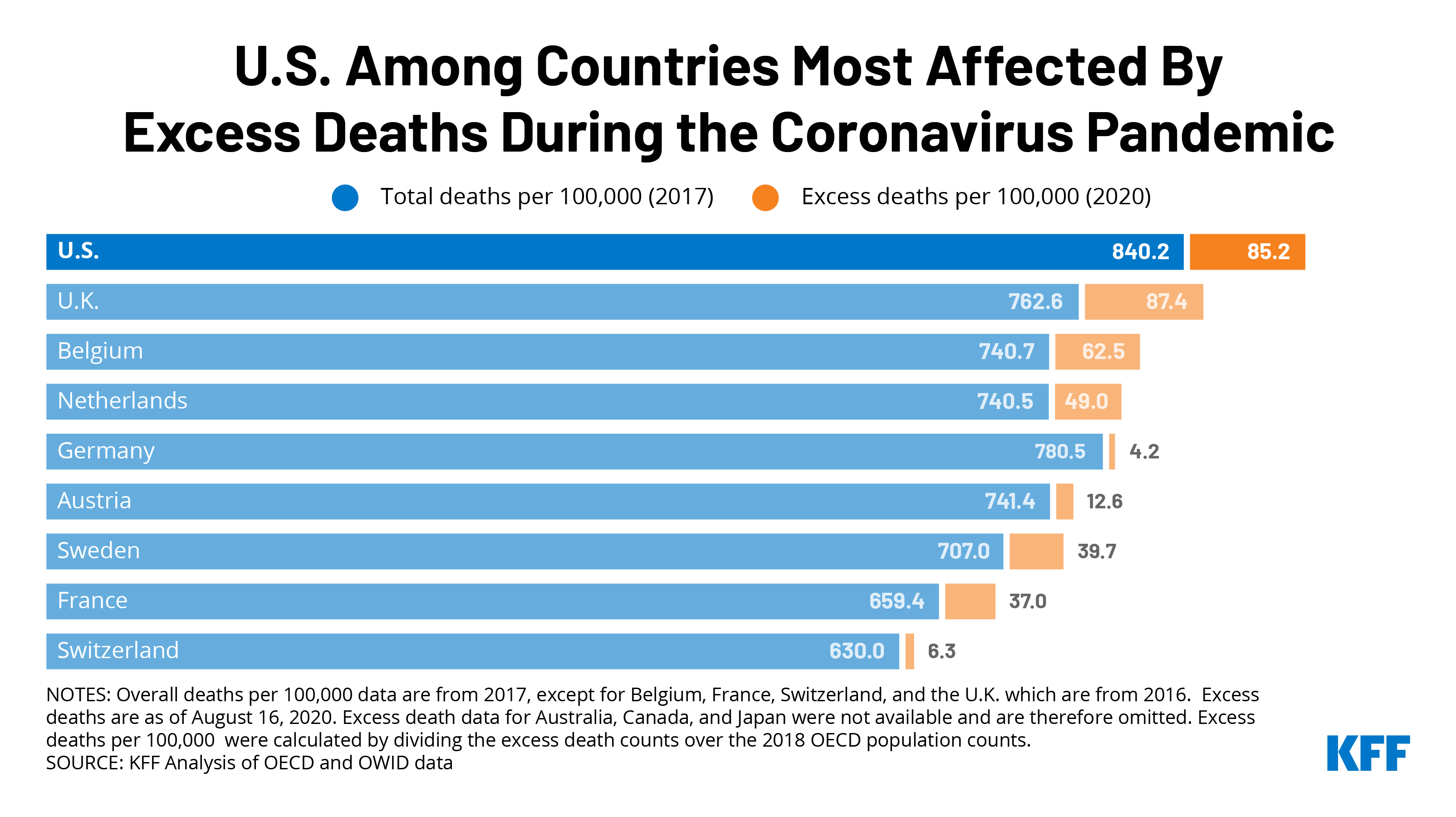

3. The importance of health coverage is even greater as coronavirus cases are surging. In recent days, the number of new coronavirus infections reached record highs in the U.S., and the pandemic is worsening rapidly in parts of the country that had previously been spared. A KFF analysis earlier this year showed that the cost of COVID-19 treatment for those requiring hospitalization could easily top ten thousand dollars, with more severe cases costing tens of thousands of dollars. Many private insurers have waived out-of-pocket costs for people needing COVID-19 treatment. At the very least, people with ACA-compliant private insurance are protected by out-of-pocket maximums, limiting how much enrollees must pay for a hospitalization. There is currently no guarantee that hospitals waive COVID-19 treatment costs for uninsured patients, meaning those without coverage could be on the hook for large medical bills.

4. Changes are taking place for 2021: premiums are dropping in many areas, as new insurers enter the Marketplaces. On average, marketplace benchmark premiums are declining by more than 2% in 2021 across the country (Table 1). In addition, new insurers are entering the Marketplace or expanding their service area in many states next year. These changes can increase plan choices and improve affordability for people who don’t qualify for Marketplace subsidies. People already enrolled in Marketplace plans with subsidies who want to renew coverage for 2021 are strongly advised to actively renew coverage, and not rely on Marketplace automatic renewal procedures. Changes in 2021 premiums and plan participation can affect the amount of a person’s tax credit from year to year. Actively renewing coverage lets people update their income information and review new plan choices, ensuring they receive the most accurate subsidy for 2021.

| Table 1: Change in the Average Lowest-Cost Premium by Metal Level Before Tax Credit, 2020-2021 for a 40-year-old | |||

| 2020 | 2021 | % Change | |

| Lowest Cost Bronze Premium | $331 | $328 | -0.9% |

| Lowest Cost Silver Premium | $442 | $436 | -1.4% |

| Lowest Cost Gold Premium | $501 | $481 | -4.0% |

| Benchmark Premium | $462 | $452 | -2.2% |

| SOURCE: KFF analysis of premium data from Healthcare.gov and review of state rate filings. | |||

5. For many people, incomes are particularly volatile this year, which can affect program eligibility and financial assistance. During the pandemic, many people have or will experience changes in income that could complicate their application for subsidies. Those who have previously been told they were ineligible for Marketplace financial assistance or Medicaid may now find out they are eligible if their income or other household circumstances have changed. An earlier KFF brief explored the various ways changes in wage income and unemployment benefits affect eligibility for Medicaid and Marketplace subsidies. Our newly released 2021 FAQs also review rules for income changes mid-year including potential tax consequences for those who mis-estimate their 2021 income. People who received Marketplace subsidies this year, will also have to report on income and sources when they file their 2020 tax return next year; FAQs provide information about how to count the $1,200 Recovery Rebate and federal supplements to weekly unemployment benefits that many received this year.

6. New State Actions: State Based Exchanges, Medicaid Expansions, and Public Options. Other new developments this year include new state-run insurance marketplaces and the first public option program. Residents of two states that have been using HealthCare.gov – Pennsylvania and New Jersey – will need to sign up through new state-run Marketplaces for 2021 and will have a longer Open Enrollment period than they’ve been used to. Currently, 37 states have adopted and implemented Medicaid expansion and both Oklahoma and Missouri plan to implement expansion by mid-2021. Additionally, the Washington state exchange has implemented a new quasi-public option, called Cascade Care, which will be offered in half of the state’s counties this year. KFF’s FAQs also provide updated information on four states that supplement marketplace subsidies with state funding.

7. Recent Trump Administration policy changes and court rulings may affect eligibility and covered benefits for some people. The KFF FAQs also include updated information related to recent Trump Administration actions and court rulings that may affect eligibility or covered benefits for some consumers. These include expanded exemptions for employers who refuse to cover contraceptive services based on religious or moral objections, and changes to the “public charge” test for certain individuals applying for green card status who use certain government services. The FAQs also provide information about private websites offering alternative enrollment pathways for people seeking marketplace plans and subsidies, and about short-term policies.

8. Enrollment help is available, though may be in short supply. Consumers in most states can get help from trained experts (Navigators) who won’t try to sell them anything. However, federal government funding for Navigators remains limited, with no funding for Navigators in South Carolina or Utah. In several other states, including Texas, Ohio, Illinois, Kansas, and Michigan, many counties will not be served by federal navigator programs. KFF finds nearly 5 million consumers tried to find enrollment help during the last Open Enrollment but could not. Among those who found help, about one in five heard about it through an advertisement or news coverage.

9. People affected by natural disasters or the COVID-19 disaster can apply for extended time to sign up for 2021 coverage. As in past years, people who live in FEMA-designated areas affected by hurricanes, wild fires, or other disasters – can get more time to sign up for 2021 coverage if you are unable to enroll by the end of Open Enrollment. This extension may also be available to residents throughout the US who are unable to sign up on time due to the COVID-19 disaster. The time extension is not automatic, and must be requested from the Marketplace call center.

10. There is still time to sign up for 2020 coverage. Even as this year winds down, people who lost coverage earlier this year due to the pandemic can still sign up for 2020 coverage because of a time extension for special enrollment periods (SEP). Normally, people have just 60 days to apply for a special enrollment period after they lose other coverage, but during the pandemic, those who lost coverage at any time during 2020 can still apply for an SEP to get coverage for the remainder of this year. In 3 states (Maryland, New York, and the District of Columbia), all residents who are uninsured, no matter the reason, can still sign up for 2020 coverage.

With so much changing this year, there is no shortage of reasons why the public needs to know about ACA open enrollment. KFF features more than 300 Frequently Asked Questions about the Health Insurance Marketplace and the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Spanish-language translations are also available. KFF Open Enrollment information materials also include an ACA Marketplace Subsidy Calculator, a subsidy explainer, and state-level data on premium changes. FAQs also focus on information of particular interest to young adults, women, immigrants, early retirees, non-traditional households, and people with employer-based health benefits.