Key Takeaways

Reflecting ongoing residential segregation patterns rooted in contemporary and historic policies, Hispanic, Black, Asian, and AIAN adults feel less safe in their homes and neighborhoods and experience higher rates of police mistreatment compared to White adults. Hispanic, Black, Asian, and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) adults are significantly less likely than White adults to say they feel “very safe” in their neighborhoods and in their homes, and about one in ten in each of these groups say they or a family member was a victim of violence in the past year, about twice the share of White adults who say so. About one in six AIAN adults and one in ten Black and Hispanic adults say they or a family member living with them have been threatened or mistreated by the police in the past year compared with 4% of White adults. Black and Hispanic adults who have self-reported darker skin tones report even higher rates of police mistreatment. Hispanic, Black, and AIAN adults also report disproportionate challenges with finances and employment due to underlying structural inequities, which are reflected in their daily worries and concerns. Among adults overall and across most racial and ethnic groups, having a strong network of local support is associated with increased feelings of safety in their homes and neighborhoods and reduced frequency of worries and concerns about meeting their family’s basic needs and health.

At least half of AIAN, Black, and Hispanic adults and about four in ten Asian adults say they have experienced at least one type of discrimination in daily life at least a few times in the past year, and they are more likely to say these experiences were due to their race or ethnicity compared to their White counterparts. These experiences include receiving poorer service than others at restaurants or stores, people acting as if they are afraid of them, people acting as if they are not smart, being threatened or harassed, or being criticized for speaking a language other than English. Overall, four in ten Black adults and about three in ten Hispanic, Asian, and AIAN adults say they have experienced at least one of these acts of discrimination in the past year and that their race or ethnicity was a reason for these experiences compared with just 6% of White adults.

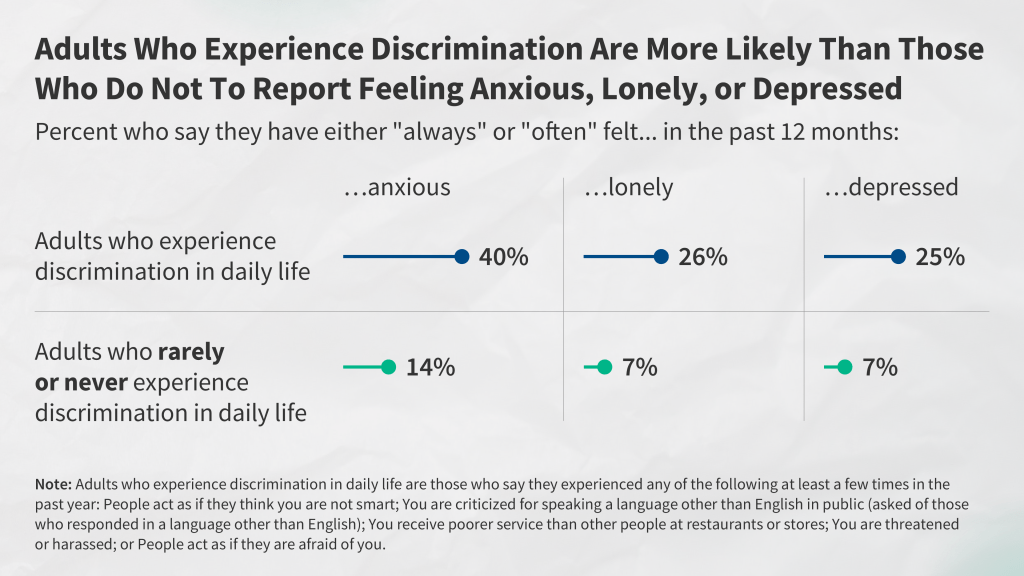

Highlighting the impacts of racism and discrimination on well-being and health, people who report experiences with discrimination in daily life are more likely than those who rarely or never experience discrimination to report adverse effects from worry or stress as well as regular feelings of loneliness, anxiety and depression. For example, those who experienced discrimination in their everyday lives are at least twice as likely as those who report rarely or never experiencing discrimination to say that in the past 30 days worry or stress has led to sleep problems (65% vs. 35%); poor appetite or overeating (52% vs. 20%) frequent headaches or stomachaches (41% vs. 15%); difficulty controlling their temper (34% vs. 11%); worsening of chronic conditions (19% vs. 9%); or an increase in their alcohol or drug use (19% vs. 6%). Similarly, those who have experienced discrimination are more likely than those who haven’t had these experiences to say they always or often felt anxious, lonely, or depressed in the past year. These patterns are similar across racial and ethnic groups and persist even when controlling for other factors like age, income, gender, and LGBT identity.

Black and AIAN adults report facing particularly high rates of discrimination, and among Black adults, those with self-reported darker skin tones are more likely to report discrimination experiences than those with lighter skin tones. AIAN and Black adults are the most likely to report an experience with discrimination in daily life asked about in the survey, with over half of both groups saying they experienced at least one of these types of discrimination at least a few times a year and about three in ten reporting experiencing two or more of these types of discrimination at least a few times a year. Among Black adults, those who say their skin color is “very dark,” “dark,” (62%) or “medium” (55%) are more likely to report an experience with discrimination compared with 42% of Black adults who say their skin color is “very light” or “light.”

Specific discrimination experiences also vary by gender, with Black men being the most likely to say people act as if they are afraid of them and Hispanic women most likely to say they are treated as if they are not smart. About a quarter (27%) of Black men say people acted afraid of them in the past year, as do 17% of Hispanic men and 17% of Black women, compared with about one in ten among Hispanic women and White and Asian adults of either gender. Conversely, the share who say they were treated as if they are not smart is higher among Hispanic women (37%) than Hispanic men (27%). Hispanic women are also more likely than Hispanic men to say they received poorer service than others in stores or restaurants at least a few times in the past year (29% vs. 21%). Discrimination experiences also vary by LGBT identity and age. About two-thirds (65%) of LGBT adults say they experienced at least one form of discrimination measured in the survey in the past year compared to four in ten (40%) non-LGBT adults, although there are no significant differences by race and ethnicity among LGBT adults. Similarly, over half (54%) of adults ages 18-49 report these experiences compared to three in ten (29%) of those ages 50 and over.

Experiences with unfair treatment extend into health care, with Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and Asian adults reporting higher levels of unfair treatment when seeking health care than their White counterparts, and Black women report even higher rates of unfair treatment. About one in five Black adults (18%) and about one in ten Hispanic (11%), Asian (10%) and AIAN (12%) adults say they have been treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health care provider in the past three years because of their race or ethnic background compared with 3% of White adults. Among Black adults, women are more likely than men to say they were treated unfairly by a health care provider because of their racial or ethnic background (21% vs. 13%).

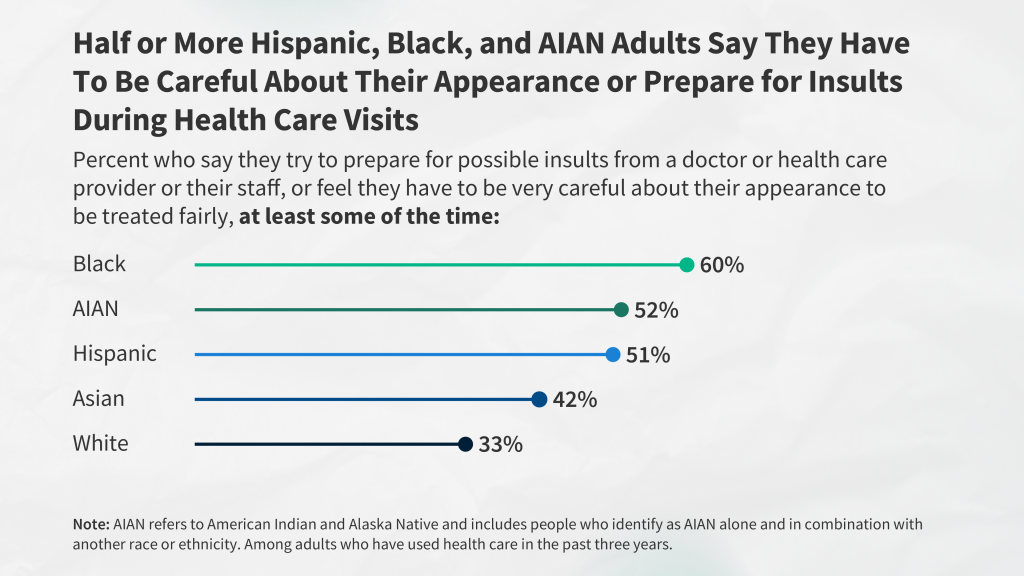

Reflecting experiences with unfair treatment, large shares of Black, AIAN, Hispanic, and Asian adults say they prepare for possible insults or feel they must be very careful about their appearance to be treated fairly during health care visits. Six in ten (60%) Black adults, about half of AIAN (52%) and Hispanic (51%) adults, and four in ten (42%) Asian adults say they prepare for possible insults from providers or staff and/or feel they must be very careful about their appearance to be treated fairly during health care visits at least some of the time compared with one in three (33%) White adults.

Having providers with a shared background matters, as Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults who have more health care visits with providers who share their racial and ethnic background report more frequent positive and respectful interactions. Reflecting limited racial and ethnic diversity of the health care workforce, most Hispanic, Black, Asian, and AIAN adults say that fewer than half of their health care visits in the past three years were with a provider who shared their racial or ethnic background. However, the survey shows how provider racial and ethnic concordance can make a difference in patient interactions. For example, Black adults who had at least half of recent visits with a provider who shares their background are more likely than those who have fewer of these visits to say that their doctor explained things in a way they could understand (90% vs. 85%), involved them in decision-making about their care (84% vs. 73%), understood and respected their cultural values or beliefs (84% vs. 76%), or asked them about social and economic factors (39% vs. 24%) during recent visits.

A third of adults overall report at least one of several negative experiences with a health care provider in the past three years, and many Black, Hispanic, Asian, and AIAN adults say they were treated this way because of their race or ethnicity. These negative experiences include a provider assuming something about them without asking, suggesting they were personally to blame for a health problem, ignoring a direct request or question, or refusing to prescribe pain medication they thought they needed. About a quarter (24%) of Black adults and one in five (19%) AIAN adults say they experienced at least one of these negative experiences and that their race or ethnicity was a reason why they were treated this way, as do 15% of Hispanic and 11% of Asian adults, compared with just 4% of White adults. Notably, 22% of Black adults who were pregnant or gave birth in the past ten years say they were refused pain medication they thought they needed, roughly twice the share of White adults with a pregnancy or birth experience (10%).

Negative experiences with health care providers as well as language access challenges have consequences for health and health care use. Among adults who used health care in the past three years, one in four (25%) say they had a negative experience (including being treated unfairly or with disrespect, a negative provider interaction, or difficulty with language access), and it led to worse health, being less likely to seek care, and/or switching providers. AIAN and Black adults are more likely than White adults to say they had a negative experience and it contributed to at least one of these consequences.

Implications

The survey reveals that, in wake of the initial COVID-19 pandemic and amid ongoing economic challenges and political division within the U.S., people’s experiences in their everyday lives and in health care settings often vary starkly by race and ethnicity, highlighting the ongoing impacts of racism and discrimination within the health care system and more broadly. The survey shows that many challenges are shared across all adults, including White adults, but that Hispanic, Black, Asian, and AIAN adults face disproportionate challenges and higher rates of unfair treatment due to their race and ethnicity, which have implications for health and well-being. The survey data identify areas for increased attention, resources, and initiatives to address these challenges and disparities, such as mechanisms to improve social and economic circumstances and provide safer communities as well as to address ongoing bias and discrimination, particularly in health care. The survey results also highlight factors that mitigate some of these challenges, including having strong local support networks and more health care visits with providers who have a shared racial and ethnic background. They also illustrate opportunities to increase respectful and positive provider interactions that can support high-quality and culturally competent care. Addressing the challenges identified in the survey is important not only from an equity standpoint but also for improving the nation’s overall health and economic prosperity.

Notes on Racial and Ethnic Groups Included in This Report

Many surveys and data analyses classify individuals into non-overlapping racial and ethnic categories using single-race and Hispanic ethnicity categories and grouping those who identify as more than one race into a “multiracial” or “other” category. To allow for better representation of experiences of the growing shares of people who identify as multiracial, this report uses an “alone or in combination” approach for classifying individuals so that they are represented within each racial and ethnic group with which they identify, resulting in overlapping racial and ethnic categories. For example, responses from someone who identifies as both Black and Asian are included in the results for both Black adults and Asian adults, and responses from someone who identifies as American Indian and Hispanic are included in the results for both AIAN adults and Hispanic adults. The exception is reporting on White adults, who in this report are defined as those who identify as non-Hispanic and select White as their only race. See Appendix 1 for more details.

The sample sizes for Hispanic adults and Black adults (more than 1,750 each) allow for detailed subgroup reporting, including by age, gender, income, LGBT identity, and urbanicity. The sample of Asian adults (693) allows for a narrower set of demographic breaks within this group. Because of the smaller sample of AIAN adults (267), results are shown for this population as a whole and demographic breaks are not provided.

In addition, the sample of AIAN adults has some limitations and caution should be exercised when interpreting these results (see Appendix 2 for a description of these limitations, adjustments made to make the sample more representative, and considerations for data interpretation). Given ongoing concerns about data erasure and invisibility of smaller populations, including Indigenous people, KFF has decided to include results for the AIAN population in this report despite these limitations.

Section 1: Racial and Ethnic Differences in Social and Economic Factors, Safety, and Police Interactions

Historic and contemporary policies contribute to ongoing structural inequities in access to opportunities and resources, shaping where people live, their education and employment, and other factors that influence their daily lives, experiences, and interactions with systems and institutions. For example, historic housing policies, including discriminatory practices such as redlining, have ongoing impacts today, including residential segregation of Black people into urban areas with fewer resources and educational opportunities and higher rates of poverty, violence and crime. The survey shows racial and ethnic differences in finances and employment, feelings of safety and exposure to violence, and interactions with the police that reflect these types of underlying inequities.

Finances and Employment

Black, AIAN, Hispanic, and Asian adults face increased challenges across an array of social and economic factors relative to White adults, which reflect underlying structural inequities, including access to employment and educational opportunities. About three in ten AIAN (29%) and Black (28%) adults, one quarter (24%) of Hispanic adults, and one in five (20%) Asian adults say they or a family member experienced problems getting or keeping a job in the past year compared with 15% of White adults (Figure 1). Just under half of AIAN (48%) and Black (45%) adults say they or a family member had a problem paying for food, housing, transportation, or other necessities in the past year, nearly twice the share of White adults (27%) who report these issues. Similarly, about one in five Black (22%) and AIAN (22%) adults and one in seven Hispanic adults (15%) say they have difficulty affording their bills each month, larger than the share of White adults who say this (11%). In contrast, paying for health care is a common challenge across racial and ethnic groups. At least one in five adults across racial and ethnic groups say they or a family member living with them had a problem paying for health care in the past 12 months. Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to report problems affording health care in the past year (27% vs. 23%), reflecting that they have a higher rate of being uninsured.

Differences in finances and employment may also reflect bias and discrimination, with Black and AIAN adults more likely than White adults to report unfair treatment in the workplace and in housing. About four in ten Black (42%) and AIAN (42%) adults say they have ever been paid less than other people doing the same job compared with a third (33%) of White adults (Figure 2). Black adults are also more likely than White adults to say they have ever been fired, denied a job, or denied a promotion for unfair reasons (27% vs. 20%), and Black and AIAN adults are more likely than White adults to say they have ever been evicted or denied housing (14% and 13% vs. 5%).

Safety, Exposure to Violence, and Police Interactions

Reflecting ongoing residential segregation patterns rooted in historic and contemporary policies, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and AIAN adults say they feel less safe in their homes and neighborhoods compared to White adults. Large majorities of adults across racial and ethnic groups report feeling at least somewhat safe in their neighborhoods. However, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and AIAN adults are less likely than White adults to say they feel “very safe.” Roughly half of each group say they feel very safe in their neighborhood compared to about two-thirds of White adults (Figure 3). Similarly, vast majorities of adults across racial and ethnic groups say they feel at least somewhat safe in their homes, but the shares of Black, Hispanic, and AIAN adults (61% each) and Asian adults (55%) who report feeling very safe in their home are lower than the share of White adults who say this (73%).

Having a strong network of local support is associated with increased feelings of safety. Specifically, adults who say they have “a lot” or a “fair amount” of family members or friends living near them who they can ask for help or support are more likely to say they feel “very safe” in their home or neighborhood than those who have “just a few” or no family members or friends nearby that they can ask for support. For example, among Asian adults, about six in ten (62%) of those with “a lot” or a “fair amount” of family and friends nearby say they feel very safe in their home compared with about half (47%) of those with “just a few” or no close by family and friends available for support (Figure 4). Among adults overall and across most racial and ethnic groups, this relationship between having a local support network and feelings of safety remains significant even after controlling for other demographic characteristics including education, income, gender, LGBT identity, and age.1

While few adults overall say they or a family member have been a victim of violence, the shares are higher among Hispanic, AIAN, Black, and Asian adults as well as those living in urban areas. About one in ten Hispanic (12%), AIAN (11%), Black (9%), and Asian adults (9%) say they or a family member in their household was a victim of an act of violence such as a robbery, carjacking, or shooting in the past year, about twice the share of White adults (5%) who report the same (Figure 5). Among all adults, those living in urban areas are more likely than those who live in suburban and rural communities to say they or a family member have been a victim of violence in the past year, with about one in ten Hispanic (13%), Black (12%), and White (9%) adults living in urban areas reporting this. Among those living in rural communities, however, Black adults are significantly more likely than White adults to say they or someone in their family have been a victim of violence in the past year (9% vs. 2%).

Beyond differences in safety and experiences with violence, Black, AIAN, and Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to say they or a family member experienced recent mistreatment by the police, particularly Black and Hispanic adults with self-reported darker skin tones. About one in six AIAN adults (17%) and about one in ten Black (11%) and Hispanic (8%) adults say they or a family member living with them have been threatened or mistreated by the police in the past year compared with 4% of White adults (Figure 6). For Black and Hispanic adults, the shares reporting recent police mistreatment are larger among those with self-described darker skin tones compared to those with lighter skin tones. For example, 12% of Black adults with self-described “very dark,” “dark,” or “medium” skin tones say they or a family member living with them have been threatened or mistreated by police compared to 7% of those with lighter skin tones. Similar differences occur among Hispanic adults between those with darker vs. lighter skin tones (10% vs. 5%).

Daily Worries and Concerns

People’s frequent daily worries and concerns reflect these racial and ethnic differences in finances and employment, safety, and police interactions. About one in five AIAN (23%), Black (21%), and Hispanic (18%) adults say that in the past 30 days they experienced worry or stress related to providing for their family’s basic needs either “every day” or “almost every day” compared to fewer White adults (13%) (Figure 7). Similarly, larger shares of AIAN, Black, and Hispanic adults compared to White adults say they experienced daily or near-daily worry about experiences with racism and discrimination and the possibility of someone in their family being a victim of gun or police violence. AIAN, Black, and Hispanic adults are also more likely to say they frequently experienced worry or stress related to their health in the past 30 days compared to their White counterparts. Having a strong local support network, as measured by having at least a “fair amount” of friends and family living nearby who you can ask for help or support, mitigates the frequency of worries and concerns about providing for basic needs and health among adults overall and across most racial and ethnic groups.2

Section 2: Experiences with Discrimination in Daily Life and Their Impacts on Wellbeing and Stress

Black, AIAN, Hispanic, and Asian adults are more likely to report certain experiences with discrimination in daily life compared with their White counterparts, with the greatest frequency reported among Black and AIAN adults. For example, about one-third of Black adults (35%) and about a quarter of AIAN (28%), Hispanic (25%), and Asian adults (25%) say that they received poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores at least a few times in the past year, all higher than the share of White adults who say the same (16%) (Figure 8). Similarly, about four in ten AIAN adults (42%) and one-third (33%) of both Black and Hispanic adults say that people have acted as if they think they are not smart at least a few times in the past year, higher than the one-quarter (26%) of White adults who say so. In addition, Asian (17%) and Black adults (16%) are somewhat more likely than White adults (13%) to say they were threatened or harassed at least a few times in the past year. Further, about one in five Black (21%) and AIAN adults (19%) as well as 13% of Hispanic adults say people acted as if they were afraid of them at least a few times in the past year, compared to 9% of White adults. Among those who completed the survey in a language other than English, one-quarter (24%) say they were criticized for speaking another language in public in the past year, including 28% of Hispanic adults who responded in Spanish. Cumulatively, at least half of AIAN (58%), Black (54%), and Hispanic adults (50%) say they have experienced one of these forms of discrimination at least a few times in the past year, as do four in ten Asian adults (42%). About four in ten (38%) White adults also say they have experienced at least one of these types of discrimination in the past year.3

Black, AIAN, Hispanic, and Asian adults are more likely than White adults to report experiencing more than one of these types of discrimination. Three in ten Black (31%) and AIAN adults (28%) and about one in four Hispanic (26%) and Asian adults (25%) say they experienced at least two of these types of discrimination at least a few times in the past year, all higher than the share of White adults who say so (18%) (Figure 9).

When discrimination in daily life occurs, Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and Asian adults are far more likely than White adults to say their race or ethnicity was a factor in these experiences. Among those who say they experienced at least one form of discrimination measured in the survey, most Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and Asian adults say their race or ethnicity was a major or minor reason they were treated this way, compared to a much smaller share of White adults. Overall, four in ten Black adults (40%) and about three in ten Hispanic (30%), AIAN (30%), and Asian adults (28%) say they experienced at least one of these acts of discrimination in the past year and say their race or ethnicity was at least a minor reason for these experiences. By contrast, only 6% of White adults report this (Figure 10).

Across racial and ethnic groups, reports of experiences with discrimination in daily life are particularly high among younger adults and LGBT adults. There is a strong relationship between age and reports of discrimination in daily life, with a majority of adults ages 18-29 (62%) and about half of 30-49 year-olds (49%) reporting such experiences compared to smaller shares of those ages 50-64 (36%) and 65 and over (22%) (Figure 11). This pattern is consistent across racial and ethnic groups. Similarly, about two-thirds (65%) of LGBT adults say they experienced at least one form of discrimination measured in the survey at least a few times in the past year compared to four in ten non-LGBT adults (40%). Among LGBT adults, there are no differences by race and ethnicity, with about two-thirds of Hispanic (69%), Black (64%), and White (64%) LGBT adults reporting discrimination experiences in the past year.

A somewhat larger share of women compared to men report at least one of these discrimination experiences, but this overall pattern masks some differences in individual measures. For example, a larger share of women compared to men say they were treated as if they were not smart in the past year (33% vs. 23%), while men are more likely than women to say people acted as if they were afraid of them (14% vs. 9%).

The combination of race, ethnicity, and gender also highlights disproportionate discrimination for certain groups. For example, 27% of Black men say people acted afraid of them in the past year, as do 17% of Hispanic men and 17% of Black women. For Hispanic women and White and Asian adults of either gender, these shares are about one in ten. Conversely, the share who say they were treated as if they are not smart is higher among Hispanic women (37%) than Hispanic men (27%). Hispanic women are also more likely than Hispanic men to say they received poorer services than others in stores or restaurants at least a few times in the past year (29% vs. 21%) (Figure 12).

Black adults who self-describe as having darker skin color report more experiences of discrimination in their everyday lives compared to those with lighter skin color. Most Black adults who say their skin color is “very dark” or “dark” (62%) or “medium” (55%) report at least one of these experiences of discrimination, compared with 42% of Black adults who say their skin color is “very light” or “light.” For example, four in ten Black adults who say their skin color is “very dark” or “dark” (42%) say they have received poorer service at restaurants or stores in the past year, compared with about a quarter of those who say their skin color is “very light” or “light” (27%). Black adults with self-reported darker skin color are also more likely to say people acted as if they were afraid of them in the past year compared with those with lighter skin color (25% vs. 18%) (Figure 13).

Among Black adults, those with higher educational attainment report more experiences with discrimination compared to their counterparts with lower educational attainment. Black adults with a four-year college degree are more likely to report experiences of discrimination in their everyday lives compared to those without college education (59% vs. 52% respectively) (Figure 14). Specifically, about four in ten Black adults with a college degree (42%) say they received poorer service at restaurants or stores at least a few times in the past year compared with one-third of Black adults without a college degree (33%). Black adults with a college degree are also more likely to report people acting as if they are afraid of them compared to those without a four-year degree (28% vs. 19%). These findings are consistent with previous research, and may reflect increased exposure to perceived discrimination among those with higher incomes and education levels as well as having greater awareness of racism and therefore greater ability to identify it in different aspects of life.

Relationship Between Discrimination Experiences and Well-being

Racism is an underlying driver of health disparities and repeated and ongoing exposure to perceived experiences of racism and discrimination can increase risks for poor health outcomes. Research has shown that the exposure to racism and discrimination can lead to negative mental health outcomes and certain negative impacts on physical health, including depression, anxiety, and hypertension. Studies also show that perceived discrimination can negatively impact healthy behaviors by increasing smoking and alcohol use and lowering adherence to medical guidance and preventative screenings.

Among all U.S. adults and across racial and ethnic groups, those who report experiences with discrimination in daily life are more likely than others to report adverse effects from worry or stress such as appetite and sleep issues, increased substance use, and worsening of chronic health conditions. Adults who report experiences with at least one type of discrimination in daily life as measured in the survey are more likely than adults who “rarely” or “never” experienced such discrimination to report certain adverse effects of worry or stress. For example, those who experienced discrimination in their everyday lives are more likely than others to say that in the past 30 days worry or stress has led to sleep problems (65% vs. 35%); poor appetite or overeating (52% vs. 20%) frequent headaches or stomachaches (41% vs. 15%); difficulty controlling their temper (34% vs. 11%); worsening of chronic conditions (19% vs. 9%); or an increase in their alcohol or drug use (19% vs. 6%) (Figure 15). Overall, eight in ten (79%) adults who experienced discrimination in the past year say they have had at least one of these adverse effects of worry and stress, compared to about half (47%) of adults who say they rarely or never had these experiences in the past year. These patterns are similar across racial and ethnic groups. While other underlying factors beyond discrimination may contribute to these differences, the relationship between adverse effects of stress and experiences with discrimination remains significant even after controlling for other demographic characteristics including education, income, gender, LGBT identity, and age.4

Adults who report discrimination experiences in daily life are more likely than those who say they rarely or never experience discrimination to report always or often feeling lonely, depressed, or anxious in the past 12 months. Among those with discrimination experiences, four in ten (40%) say they “always” or “often” felt anxious in the past year, compared to 14% of adults who rarely or never experience such discrimination. Those with discrimination experiences in their daily life are more than three times as likely as others to say they always or often felt lonely (26% vs. 7%) or depressed (25% vs. 7%) in the past year (Figure 16). These patterns are similar across racial and ethnic groups and persist even after controlling for other demographic characteristics including education, income, gender and age.5

Section 3: Experiences in Health Care Settings

Reflecting underlying structural inequities in the U.S., there are ongoing racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. AIAN, Hispanic, and Black people have higher uninsured rates compared to their White counterparts and face other increased barriers to accessing care. Among adults in the survey, Hispanic (20%), AIAN (14%), and Black (10%) adults are more likely to report being uninsured compared to White (6%) adults. However, beyond differences in the ability to access care, the survey highlights differences in experiences within the health care system, including interactions with providers, experiences with unfair treatment, and the consequences of these experiences.

Provider Interactions

Among those who used health care within the past three years, most adults across racial and ethnic groups report having positive and respectful interactions with their health care providers most of the time. Health care that is respectful and responsive to individual preferences, needs, and values is an important component of health care quality and equitable health care. Among those who used health care in the past three years, large shares say that their health care providers explained things in a way they could understand (89%), respected their cultural values and beliefs (84%), involved them in decision-making about their care (81%), and spent enough time with them (76%) most of the time or every time during visits. Across racial and ethnic groups, at least two-thirds say their provider did each of these things at least most of the time.

However, Hispanic, Black, Asian, and AIAN adults report having these positive and respectful interactions with health care providers less often than White adults. For example, AIAN (18%), Asian (18%), and Hispanic (16%) adults are about twice as likely as White adults (8%) to say their health care providers explained things in a way they could understand just some of the time, rarely, or never in the past three years (Figure 17). Similarly, about one in four AIAN adults (24%) and about one in five Black (21%), Asian (21%) and Hispanic (19%) adults say their health care providers understood and respected their cultural beliefs just some of the time, rarely, or never compared with about one in ten White adults (12%). These groups also are more likely than their White counterparts to say their providers did not frequently involve them in decision-making about their care during their visits in the past three years. Many of these racial and ethnic differences persist among adults with higher incomes and those with health coverage. Among Hispanic adults there also are some differences by English proficiency. For example, Hispanic adults who have limited English proficiency are about twice as likely as those who are English proficient to say they their providers rarely or never involved them in decision-making about their care in the past three years (16% vs. 9%).

Few adults across racial and ethnic groups say a health care provider frequently asked them about their work, housing situation, or access to food or transportation in the last three years. While health coverage and access to health care shape health, social and economic factors, such as employment, housing, food access, and transportation also play a major role. Research indicates that screening for social and economic risks can positively impact health, and there are growing efforts among some providers focused on serving low-income populations to screen for social risks and needs. However, just over one in four (27%) adults who used health care in the last three years say a health care provider asked about their work, housing situation, or access to food or transportation at least most of the time during visits (Figure 18). Overall, and among Hispanic and Asian adults, lower income adults are more likely than higher income adults to say a provider asked about these factors most of the time or every time, but majorities of lower income adults still say this happens just some of the time, rarely, or never.

Reflecting limited racial and ethnic diversity of the health care workforce, Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and Asian adults are less likely than White adults to say most of their recent health care visits were with a provider who shares their racial and ethnic background. At least half of Black (62%), Hispanic (56%), AIAN (56%) and Asian (53%) adults who used health care in the past three years say that fewer than half of their visits were with a provider who shared their racial and ethnic background (Figure 19). In contrast, about three-quarters (73%) of White adults say that half or more of their visits were with a provider who shares their racial and ethnic background.

Black, Hispanic and Asian adults who have at least half of their visits with providers who share their racial or ethnic background report having more frequent positive and respectful interactions with providers. For example, among those who used health care in the past three years, Black adults who had at least half of recent visits with a provider who shares their background are more likely than those who have fewer of these visits to say that their doctor explained things in a way they could understand (90% vs. 85%), involved them in decision making about their care (84% vs. 73%), understood or respected their cultural values or beliefs (84% vs. 76%), or asked them about social and economic factors (39% vs. 24%) at least most the time (Figure 20). Patterns are similar for Hispanic adults. Asian adults who had half or more visits with a provider who shared their racial or ethnic background are more likely than those who had fewer such visits to say their provider understood and respected their cultural values and beliefs every time or most of the time.

Despite these differences, few Black, Hispanic, Asian, and AIAN adults say they think they either would or do receive better care from health care providers who share their racial and ethnic background. About a quarter of Black (27%), Hispanic (26%), and Asian adults (24%) and about one in five AIAN adults (19%) say they think they would receive better care from doctors who share their racial or ethnic background, while majorities in each of these groups say they don’t think the race or ethnicity of their provider makes much difference in the quality of care they receive. Other research has shown an association between patients and providers having shared racial and ethnic backgrounds and improved communication but mixed impacts of this patient-provider concordance on patient experiences and health outcomes. However, other recent research suggests racial concordance may contribute to improved health care use and health outcomes including lower emergency department use, reductions in racial disparities in mortality for Black infants, and increased visits for preventative care and treatment.

Experiences with Unfair Treatment by Health Care Providers

About one in five (18%) Black adults and roughly one in ten AIAN (12%), Hispanic (11%), and Asian (10%) adults who received health care in the past three years report being treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health care provider because of their racial or ethnic background. These shares are higher than the 3% of White adults who report this. Among Black adults, women are more likely than men to say they were treated unfairly by a health care provider because of their racial or ethnic background (21% vs. 13%). AIAN (26%) and Black (18%) adults also are more likely than White adults (13%) to say they have been treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health care provider in the past three years due to some other factor, such as their gender, health insurance status, or ability to pay for care (Figure 21). Overall, roughly three in ten (29%) AIAN adults and one in four (24%) Black adults say they were treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health care provider in the past three years for any reason compared with 14% of White adults. Additionally, LGBT adults are about twice as likely as non-LGBT adults to say they experienced unfair treatment by health care provider for any reason in the past three years (33% vs. 15%). Among LGBT adults, similar shares of Black (33%), White (33%), and Hispanic adults (26%) report these experiences.

Reports of unfair treatment by health care providers due to race and ethnicity persist among Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults with higher incomes, who have health coverage, or who have a usual source of care. Overall and among Hispanic adults, those with lower incomes are more likely than those with higher incomes to report unfair or disrespectful treatment by a provider in the past three years. However, even among those with higher incomes (annual household incomes of $90,000 or more), 15% of Black adults report being treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health care provider because of their race or ethnic background, as do higher shares of Asian (8%) and Hispanic (5%) adults compared with White adults (1%) (Figure 22). Among adults with health coverage, 18% of Black adults and one in ten Asian (11%) and Hispanic (10%) adults say they have been treated unfairly by a health care provider in the past three years because of their race or ethnicity compared with 3% of White adults. Similarly, among adults with a usual source of care, one in five Black adults (18%) and about one in ten Hispanic (9%), and Asian (9%) adults report being treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health care provider due to their race or ethnic background compared with just 3% of White adults.

In Their Own Words: Descriptions of Being Treated Unfairly or Disrespectfully by Health Care Providers

In open-ended responses describing instances of unfair treatment, individuals describe experiences such as not being taken seriously or not being believed about pain, rude or harassing behavior, assumptions being made about them, and being blamed for health conditions or problems they were experiencing:

“I went to the hospital with a 104 temperature and a UTI. While I understand the nurses and doctors wanted to run all tests possible, I was given more than three tests to check for STDs. I have had UTIs before and expressed that STDs were not a concern (due to sexual inactivity), and each nurse told me that ‘typically, people from my background have unprotected sex, so it is the hospitals policy to check us multiple times (even if the test results come back negative)’” – 30-year-old multiracial (Black and White) woman from Tennessee

“I am overweight and Latino with a doctorate degree. Most times when the nurse staff does intake, they often assume I work an hourly job and are surprised I am a professor. I often have to dress up for appointments or wear my university’s logo to signal where I work. I often notice I am listened to more and involved in care decisions when I do this change.” – 30-year-old Hispanic man from Illinois

“After having surgeries within a year of each other, I had questions about aftercare and issues that I was experiencing but the doctors did not take my concerns seriously and shunned me off. Unfortunately, both times there were serious complications that resulted in further health issues and irreparable health conditions.” – 63-year-old Black woman from Mississippi

“White male doctors tend to give me the worst care. I once saw a doctor about breathing issues, and he told me I was probably just thinking too hard about breathing which was probably causing the issues. Turns out I have asthma.” – 44-year-old Asian woman from California

“After having a c-section nurse would not listen to my complaints about the pain that I was experiencing. My White husband had to explain that I was worried it might have to do with the preeclampsia that I had.” – 35-year-old Black woman from Florida

“The doctor scolded me for not maintaining healthy lifestyle just by looking at my diabetes counts and not trying to understand my situation where I was between jobs and insurance, so wasn’t not able to take medications on time which caused the fluctuations that caused the counts in my blood sugar levels.” – 41-year-old Asian man from California

Reflecting these experiences with unfair treatment, large shares of Black, AIAN, Hispanic and Asian adults say that they prepare for possible insults from a provider or staff or feel they need to be very careful about their appearance to be treated fairly during health care visits. Vigilant behaviors, such as preparing for insults or considering one’s appearance, are sometimes adopted by people who experience discrimination as a means of protection from the threat of possible discrimination and to reduce exposure. Research has shown that heightened vigilance is associated with poor physical and mental health outcomes, including hypertension, sleep difficulties, and depression. Over half (55%) of Black adults, about half of AIAN (49%) and Hispanic (47%) adults, and about four in ten (39%) Asian adults say they feel they must be very careful about their appearance at least some of the time to be treated fairly when receiving health care (Figure 23), including one in five (21%) Black adults who say they feel they have to be careful “every time.” Each of these groups is more likely than White adults to report being vigilant about their appearance during health care visits at least some of the time, although notably about three in ten (29%) White adults say they take these actions. About three in ten (29%) Black adults and roughly a quarter of AIAN (26%) and Hispanic (23%) adults say they try to prepare for possible insults during health care visits, all higher than the share of White adults who say this (16%). About one in five Asian adults (19%) also report preparing for insults. Together, six in ten (60%) Black adults, about half of AIAN (52%) and Hispanic (51%) adults, and about four in ten (42%) Asian adults say they engage in at least one of these practices at least some of the time during health care visits compared with one in three (33%) White adults. These shares are also particularly high among LGBT adults across racial and ethnic groups, with at least six in ten Black (63%), Hispanic (61%), and White (60%), LGBT adults saying they take either of these steps.

Among higher income adults and those with health coverage, Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults remain more likely than White adults to say they prepare for insults during health care visits or feel they need to be very careful about their appearance to be treated fairly at least some of the time. While higher income adults generally are less likely than those with lower incomes to say they take these steps, among those with higher incomes ($90,000 or more annually), about half of Black adults (51%) and about four in ten Hispanic (41%) and Asian (38%) adults say they take either of these steps at least some of the time during health care visits, higher than the share of White adults (22%) who say this. Similarly, among adults with coverage, Black (59%), Hispanic (51%), and Asian (42%) adults are more likely than their White (34%) counterparts to say they take either of these steps at least some of the time, including 47% of insured Black adults who say they feel they have to be very careful about their appearance (Figure 24).

Negative Experiences When Receiving Health Care

A third of adults who received health care in the past three years report at least one of several negative experiences with a health care provider, including a provider assuming something about them without asking, suggesting they were personally to blame for a health problem, ignoring a direct request or question, or refusing to prescribe pain medication they thought they needed. While many of these negative experiences are shared across racial and ethnic groups, including White adults, AIAN adults are more likely than their White counterparts to say a provider assumed something without asking (29% vs. 19%), ignored a direct request or question (29% vs. 15%), and refused to prescribe pain medication they thought they needed (19% vs. 9%) (Figure 25). In addition, Black adults are more likely than White adults to say a provider ignored a direct request or question (19% vs. 15%) or refused them pain medication they thought they needed (15% vs. 9%). These differences persist among Black adults with health coverage but are not significant after controlling for income.

AIAN, Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults are more likely than White adults to say they had at least one of these negative experiences with a health care provider due to their race and ethnicity. Among adults who received health care in the past three years, about a quarter (24%) of Black adults and one in five (19%) AIAN adults say they experienced at least one of these negative experiences and that their race or ethnicity was a major or minor reason why they were treated this way, as do 15% of Hispanic and 11% of Asian adults. Just 4% of White adults who received care report a negative experience due to their race or ethnicity.

White and Asian women are more likely than their male counterparts to report at least one of these negative experiences with health care providers, but there are no significant differences between Hispanic and Black women and men. Among adults overall, the largest differences by gender include women being more likely than men to say a provider assumed something without asking and a provider ignoring a direct request or question (Figure 26). Additionally, 22% of Black adults who were pregnant or gave birth in the past ten years say they were refused pain medication they thought they needed, roughly twice the share of White adults with a pregnancy or birth experience (10%).

Among adults with limited English proficiency, about half (48%) say that difficulty speaking or reading English made it difficult to complete at least one of several activities related to using health care in the past three years. These activities include filling out forms at a doctor’s office (34%), communicating with staff at a doctor’s office (33%), understanding instructions from a health care provider (30%), filling a prescription or knowing how to use it (27%), or scheduling a medical appointment (25%).

One in four adults who used health care in the past three years report that they had one or more of these negative experiences with a health care provider and/or a language access challenge and that it resulted in worse health, them being less likely to seek care, and/or them switching providers. About four in ten (39%) AIAN adults and three in ten (30%) Black adults say they had a negative experience with one of these consequences compared with about one in four (24%) White adults (Figure 27). The shares of Hispanic and Asian adults reporting a negative experience with at least one of these consequences are similar to that of White adults.

Implications

The survey reveals that, in wake of the initial COVID-19 pandemic and amid ongoing economic challenges and political division within the U.S., people’s experiences in their everyday lives and in health care settings often vary starkly by race and ethnicity, highlighting the ongoing impacts of racism and discrimination within the health care system and more broadly. The survey shows that many challenges are shared across all adults, including White adults, but that Hispanic, Black, Asian, and AIAN adults face disproportionate challenges and higher rates of unfair treatment due to their race and ethnicity, which have implications for health and well-being. The survey data identify areas for increased attention, resources, and initiatives to address these challenges and disparities, such as mechanisms to improve social and economic circumstances and provide safer communities as well as to address ongoing bias and discrimination, particularly in health care. The survey results also highlight factors that mitigate some of these challenges, including having strong local support networks and more health care visits with providers who have a shared racial and ethnic background. They also illustrate opportunities to increase respectful and positive provider interactions that can support high-quality and culturally competent care. Addressing the challenges identified in the survey is important not only from an equity standpoint but also for improving the nation’s overall health and economic prosperity.