Prior Authorization Process Policies in Medicaid Managed Care: Findings from a Survey of State Medicaid Programs

Note: This brief was updated on Aug. 21, 2025, to include Kentucky in the count of states that require Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) to make standard prior authorization decisions within a timeframe shorter than 7 calendar days.

Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) deliver care to three-quarters of all Medicaid enrollees nationally. MCOs often require patients to obtain approval of certain health care services or medications before the care is provided—an insurance practice commonly referred to as “prior authorization”. This allows the MCO to evaluate whether care is covered, medically necessary, and being delivered in the most appropriate setting. If the MCO determines the requested service (or medication) is not appropriate or medically necessary, the MCO may deny the request (fully or partially). Providers and patients have raised concerns that MCO prior authorization processes have the potential to delay or limit access to care. A 2023 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that Medicaid MCOs had an overall prior authorization denial rate (12.5%) that was more than double the Medicare Advantage rate (5.7%). OIG found most Medicaid enrollees (89%) do not appeal to the MCO for reconsideration. Of those who do appeal, only about one-third get the initial denial overturned—far less than for Medicare Advantage appeals (82% overturn rate). They also found limited state Medicaid agency oversight. The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) has highlighted similar concerns, making recommendations to improve state monitoring and oversight, transparency, and the enrollee experience.

To help reduce prior authorization-related burden, the Biden Administration issued the Interoperability and Prior Authorization final rule in 2024 aimed at streamlining and automating the prior authorization process and improving transparency for Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace health plans. A growing number of states have also introduced limits on prior authorization requirements through state legislation. In June 2025, under the Trump Administration, HHS announced a voluntary initiative where dozens of health insurers pledged to reduce the burden of prior authorizations across insurance markets. The pledge included commitments to require prior authorization less often, speed up the timeframe to review prior authorization requests, and use clearer language when communicating with patients. A recent KFF poll found that about three-quarters (73%) of adults say that health insurance related delays and denials are “a major problem,” and few people think it is likely that health insurance companies will follow through on the new pledge in a meaningful way.

To improve understanding of state Medicaid managed care prior authorization processes and oversight, the 24th annual Medicaid budget survey, conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) in the summer of 2024, asked about specific prior authorization process-related policies in place as of July 1, 2024. Key findings include:

- Prior Authorization Decision Timeframes. Half of responding MCO states (18 of 36) required MCOs to make “standard” prior authorization decisions within 7 calendar days or a shorter timeframe. New federal rules that take effect in January 2026 require standard prior authorization decisions to be made within 7 calendar days.

- Offering of Electronic Denial Notices. Only about one-third of responding MCO states (12 of 38) required MCOs to offer prior authorization denial notices electronically. Delayed receipt of denial notices can leave enrollees without enough time to request an appeal.

- Access to External Medical Review. At least one-third of responding MCO states (15 of 39) provided enrollees with access to an independent external medical review process to review an MCO’s decision to uphold a denial.

Prior Authorization Process Overview

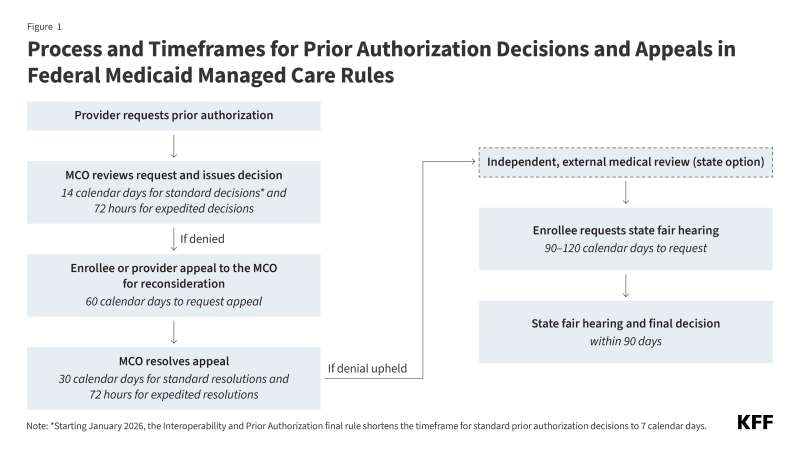

Prior authorization is a multi-step process where payers require medical providers to receive approval before providing a specific service, item, or medication. Federal regulations allow Medicaid MCOs to limit services based on medical necessity (must be no more restrictive than fee-for-service (FFS)) and for the purpose of utilization control if certain conditions are met.1 Federal rules also establish timeframes and processes MCOs must follow when making prior authorization and appeals decisions (Figure 1). State Medicaid agencies may impose stricter requirements on MCOs than set forth in federal regulations for prior authorization processes and timelines.

Survey Findings

Prior Authorization Decision Timeframes

Federal rules currently require MCOs to make “standard” prior authorization decisions within 14 calendar days and “expedited” decisions within 72 hours of prior authorization requests; however, states may establish shorter timeframes. Starting January 2026, the Interoperability and Prior Authorization final rule shortens the timeframe for standard prior authorization decisions to 7 calendar days. (The timeframe for expedited prior authorization decisions in Medicaid managed care is unchanged by the final rule.) The 2024 KFF/HMA state survey asked states how their current MCO requirements compare to the final prior authorization rule’s timeframe standards.

Half of responding MCO states (18 of 36) reported requiring standard prior authorization decisions within 7 calendar days (8 states) or a shorter timeframe (10 states) (Table 1). Eighteen states reported requiring a timeframe longer than 7 calendar days for standard prior authorization decisions. For expedited prior authorization requests, about one-third of responding MCO states (13 states) reported having a standard shorter than 72 hours, while 23 states reported having a 72-hour standard.

Denial Notices and Enrollee Support

About one-third of responding MCO states (12 of 38) require MCOs to offer electronic denial notices (Figure 2). MACPAC’s examination of denials and appeals in Medicaid managed care found that mailed denial notices often arrived late or not at all. Enrollees have 60 calendar days from the date on the denial notice to file a request for an appeal to the MCO. Delayed receipt of denial notices can leave enrollees without enough time to request an appeal. Offering an option to receive electronic notices may help enrollees receive denial notices faster and more reliably.

More than half of responding MCO states (21 of 38 states) reported using standardized prior authorization denial notice templates or language. Both MACPAC and OIG found denial notices can be lengthy and challenging to understand, often using clinical and/or legal jargon. Denial notices may be missing key information such as why the original request failed to meet medical necessity standards/requirements and what documentation the MCO may need to approve the request, which can contribute to challenges with the appeals process and result in lower appeal rates. Standardized denial notice language may improve enrollees’ ability to understand the prior authorization process and next steps. However, in a review, OIG found even template language can lack key information in some instances (e.g., one state’s template failed to inform enrollees of their right to request a state fair hearing after appealing to the MCO).

While federal rules require MCOs to provide enrollees assistance with the appeals process upon request, MACPAC found some enrollees may not have confidence in information provided by MCOs or enrollees may hesitate to seek support (in navigating the appeals process) from the entity that denied their service request. External entities like ombudsperson offices can help enrollees navigate the appeals process. Although the survey asked whether states provide Medicaid funding to external entities (e.g., state ombudsperson offices, legal aid societies) that could assist enrollees through the MCO appeals process, it’s not clear how many states provide such external funding (as it appears the question was not interpreted consistently across states).

Independent External Medical Review

Enrollees who disagree with an MCO’s prior authorization decision have the right to appeal to the MCO for reconsideration. If the managed care plan upholds the original denial, states have the option to offer an external medical review but are not required to do so. An external medical review is a clinical review of an MCO’s decision to uphold a denial by an independent, third party (not affiliated with the state or MCO). If offered, it must be at no cost to the enrollee, cannot disrupt an enrollee’s “continuation of benefits,” or be used as a deterrent to a state fair hearing (the next step in the appeals process which involves an administrative law judge). In Medicare Advantage, if the managed care plan upholds the original denial, the case is automatically sent to an independent review entity. OIG suggests that this automatic independent review process might explain why Medicare Advantage’s appeal overturn rate is 82%–far higher than Medicaid MCOs 36% overturn rate. The 2024 KFF/HMA state survey asked states whether they provide access to an external medical review process to review an MCO’s decision to uphold a denial.

As of July 1, 2024, at least one-third of responding MCO states (15 of 39) provided enrollees access to an independent external medical review process to review an MCO’s decision to uphold a denial (Figure 3).2 These findings represent a slight increase in the number of states that report providing access to external medical reviews compared to OIG’s 2019 findings.

- MCOs must ensure that the services they provide are sufficient in amount, duration, or scope to achieve the purpose for which they are furnished. Also, MCOs may not arbitrarily deny or reduce a required service based solely on an enrollee’s illness or condition. ↩︎

- States were counted as having an external review process if, in addition to their survey response, the state’s publicly available MCO contracts and/or Managed Care Program Annual Reports supported the availability or use of an external review process. ↩︎