Communities of Color at Higher Risk for Health and Economic Challenges due to COVID-19

Issue Brief

Summary

The COVID-19 outbreak presents potential health and financial challenges for families, which may disproportionately affect communities of color and compound underlying health and economic disparities. This brief analyzes data on underlying health conditions, health coverage and health care access, and social and economic factors by race and ethnicity to provide insight into how the health and financial impacts of COVID-19 may vary across racial/ethnic groups. It finds:

- Communities of color are at increased risk for experiencing serious illness if they become infected with coronavirus due to higher rates of certain underlying health conditions compared to Whites;

- Communities of color will likely face increased challenges accessing COVID-19-related testing and treatment since they are more likely to be uninsured and to face barriers to accessing care than Whites; and

- Communities of color face increased financial and health risks associated with COVID-19 due to economic and social circumstances.

Early data suggest COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting groups of color. For example, in the District of Columbia, Blacks make up 45% of the total population, but accounted for 29% of confirmed coronavirus cases and 59% of deaths as of April 6, 2020. In Louisiana, Blacks make up 32% of the total state population, but accounted for over 70% of COVID-19 deaths as of April 6, 2020. Data from Illinois show that groups of color accounted for 48% of confirmed cases and 56% of deaths as of April 6, 2020, while only making up 39% of the total state population. In North Carolina, Blacks make up 21% total state population, but accounted for 37% confirmed cases as of April 6, 2020. In Michigan, where Blacks make up 14% of the total state population, they accounted for 33% of confirmed cases and 41% of deaths as of April 6, 2020. Moreover, survey data find that Latinos are more likely than Americans overall to see COVID-19 as a major threat to health and finances.

Comprehensive data by race and ethnicity will be key for understanding the impacts of COVID-19 across communities and on health and economic disparities going forward. Data by race and ethnicity will also be important for understanding the extent to which there are disparities in access to and receipt of health and economic relief. Together these data can help shape and target response and relief efforts. Although some states and localities are reporting data by race and ethnicity, as of early April, CDC was not reporting data by race and ethnicity and these data were not available widely across states. CDC requests racial and ethnic data on its case reporting form for coronavirus, but had not indicated plans to expand reporting of these data as of early April.

Introduction

Communities of color face longstanding disparities in health and health care. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) helped narrow some disparities in health coverage, access, and utilization, but groups of color continue to fare worse compared to Whites across many of these measures as well as across measures of health status. The COVID-19 outbreak presents potential health and financial challenges for families that may disproportionately affect communities of color and compound their existing disparities in health and health care. This brief analyzes data on underlying health conditions, health coverage and health care access, and social and economic factors by race and ethnicity to provide insight into how the health and financial impacts of COVID-19 may vary across racial/ethnic groups.

Health Risks

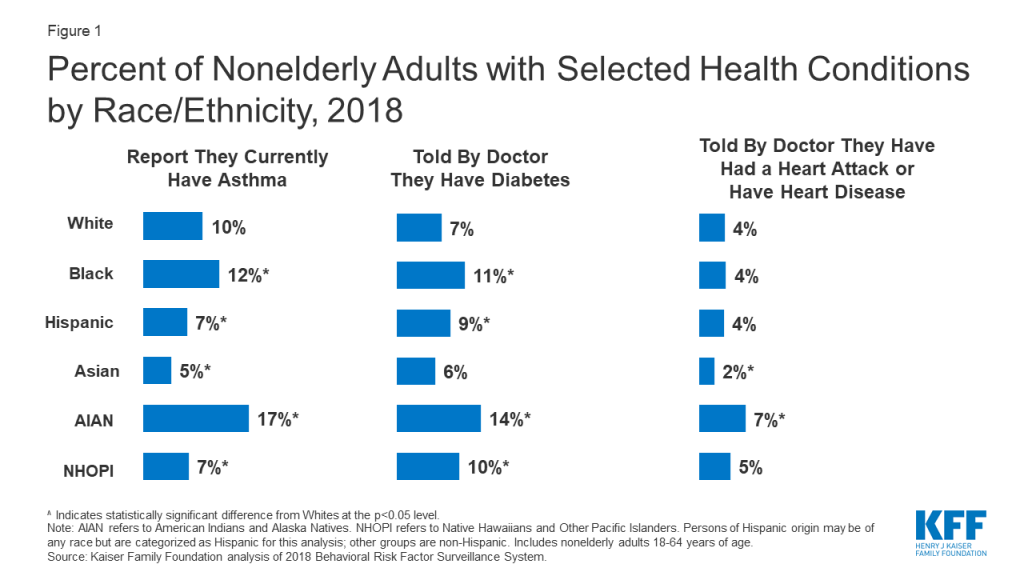

Communities of color are at increased risk for experiencing serious illness if they become infected with coronavirus due to higher rates of certain underlying health conditions compared to Whites. Older individuals; individuals with underlying health conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease, and asthma and lung disease; and immunocompromised people (e.g., those with poorly controlled HIV/AIDS or undergoing cancer treatment) have a greater risk of becoming severely ill if infected with coronavirus.1 Though groups of color generally are younger relative to Whites, they are more likely to have certain underlying health conditions. Blacks and American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) fare worse than Whites across many health status indicators; findings for Hispanics are mixed, but they face large disparities for certain measures. Overall, nonelderly Black, Hispanic, and AIAN adults are more likely than Whites are to report fair or poor health.2 Among nonelderly adults, Blacks and AIANs have higher rates of asthma and diabetes compared to Whites (Figure 1). Asthma rates also are higher for Black and Hispanic children compared to White children. Further, nonelderly adult AIANs are nearly twice as likely as Whites are to report having had a heart attack or heart disease. Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHOPI nonelderly adults and Black and Hispanic children also are more likely to be obese compared to Whites.3 Moreover, there are stark disparities in HIV/AIDS diagnosis and rates among teens and adults. Compared to Whites, Blacks have an over eight times higher HIV diagnosis rate and a nearly ten times higher AIDS diagnosis rate, and the HIV and AIDS diagnosis rates for Hispanics are more than three times the rates for Whites (Figure 2).

Access to Care

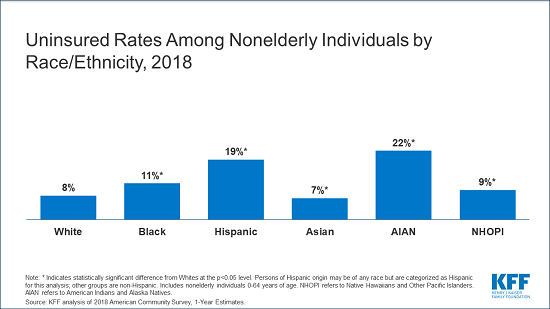

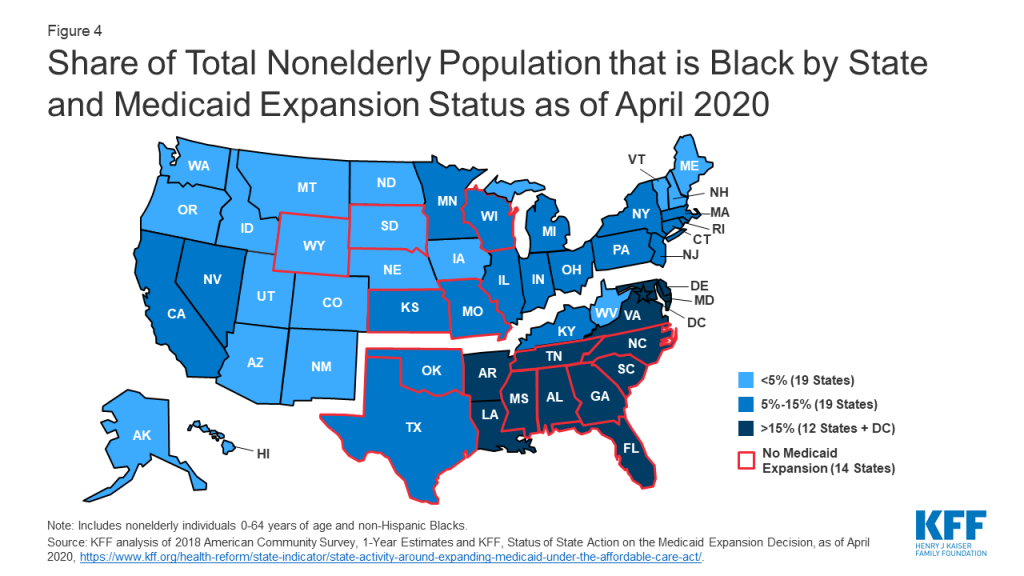

Communities of color will likely face increased challenges accessing COVID-19-related testing and treatment services since they are more likely to be uninsured compared to Whites. Congress has passed legislation to provide free testing for uninsured individuals, and the President has proposed coverage for hospital treatment costs for uninsured individuals.4 However, uninsured people may lack a usual source of care and not know where to go to obtain testing. They also may still forego testing or treatment out of fear of costs if they are not aware of the resources provided to help cover costs for uninsured individuals. Additionally, some may still face large out of pocket costs for care that these provisions might not cover, such as care received outside the hospital inpatient setting. While all racial and ethnic groups had large gains in health coverage under the ACA, Blacks, Hispanics, AIANs, and Native Hawaiians Other Pacific Islanders (NHOPIs) remain more likely to be uninsured compared to Whites. AIANs and Hispanics are at the highest risk of being uninsured, with 22% of AIANs and nearly one in five (19%) Hispanics lacking coverage compared to 8% of Whites (Figure 3). Higher uninsured rates among groups of color, in part, reflect their more limited access to affordable coverage options. Uninsured Blacks are more likely than Whites to fall in a coverage gap (15% vs. 9%) because a greater share live in states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion (Figure 4). Moreover, uninsured nonelderly Hispanics and Asians are less likely than Whites to be eligible for coverage, because they include larger shares of noncitizen immigrants who are subject to eligibility restrictions for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage.

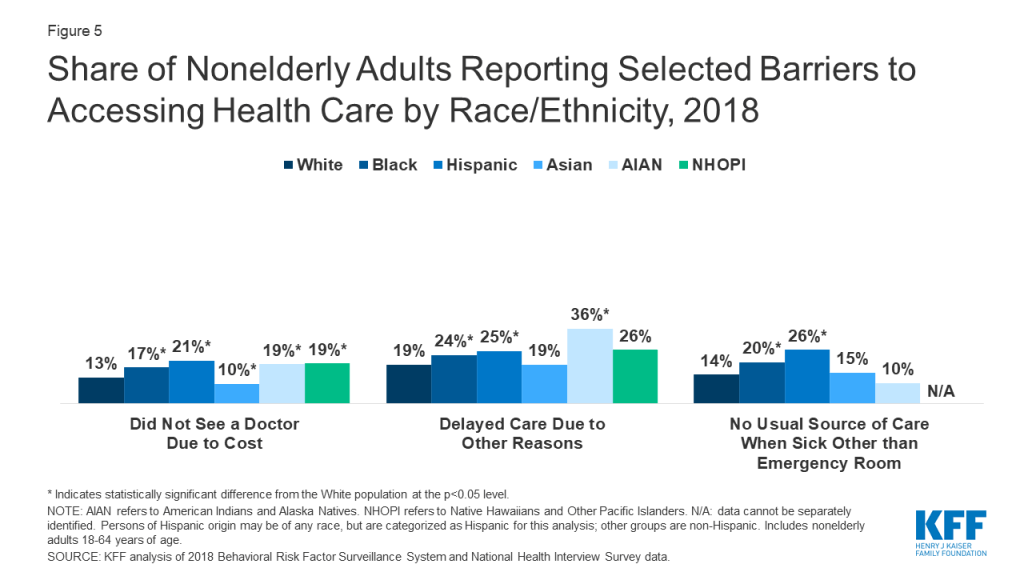

Groups of color also are more likely than Whites to report other health care access barriers. For example, among nonelderly adults, Blacks, Hispanics, AIANs, and NHOPIs are more likely than Whites to report going without needed care due to cost, and Blacks, Hispanics, and AIANs are more likely than Whites to report delaying care for reasons other than cost (Figure 5). Moreover, nonelderly Blacks and Hispanics are more likely than Whites to report no usual source of care when sick other than the emergency room (Figure 5). Although the Indian Health Services (IHS) is responsible for providing health services to AIANs and is conducting testing for coronavirus, it has historically been underfunded to meet their health care needs, leaving them facing disproportionate access barriers. Thus, Medicaid and other health coverage remains important to facilitating AIAN access to services as well as providing revenues to support IHS and Tribal facilities.

Economic and Social Challenges

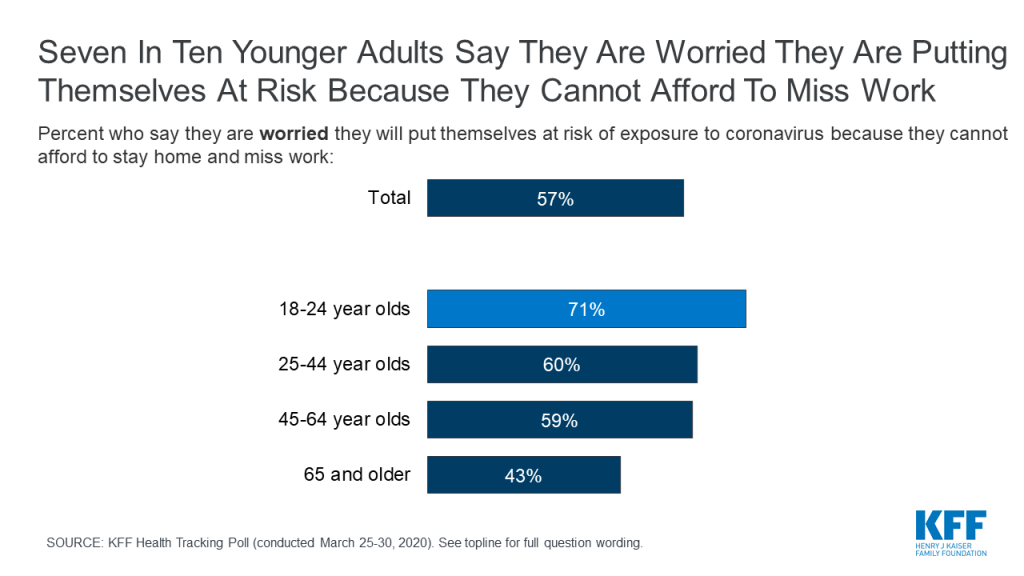

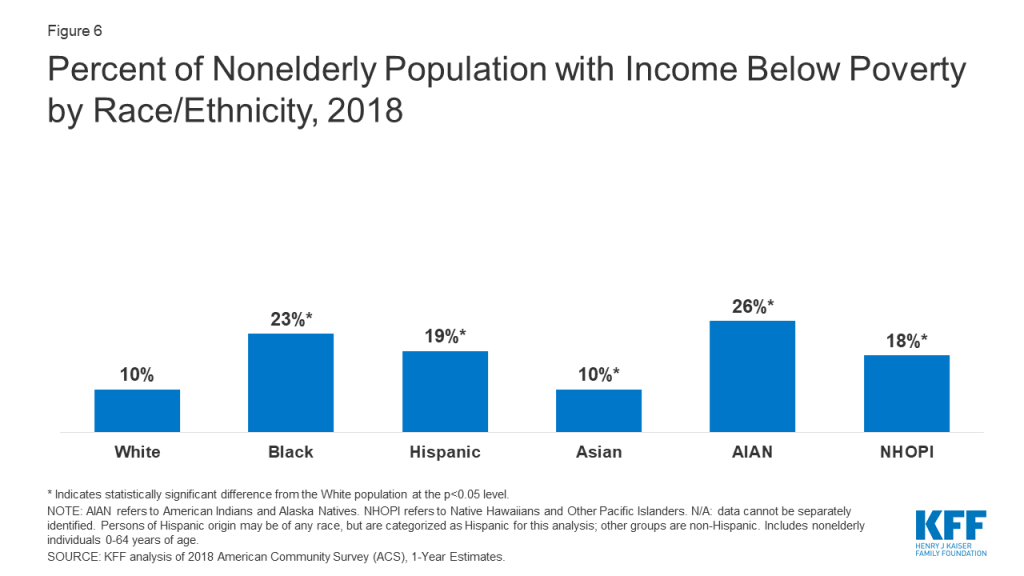

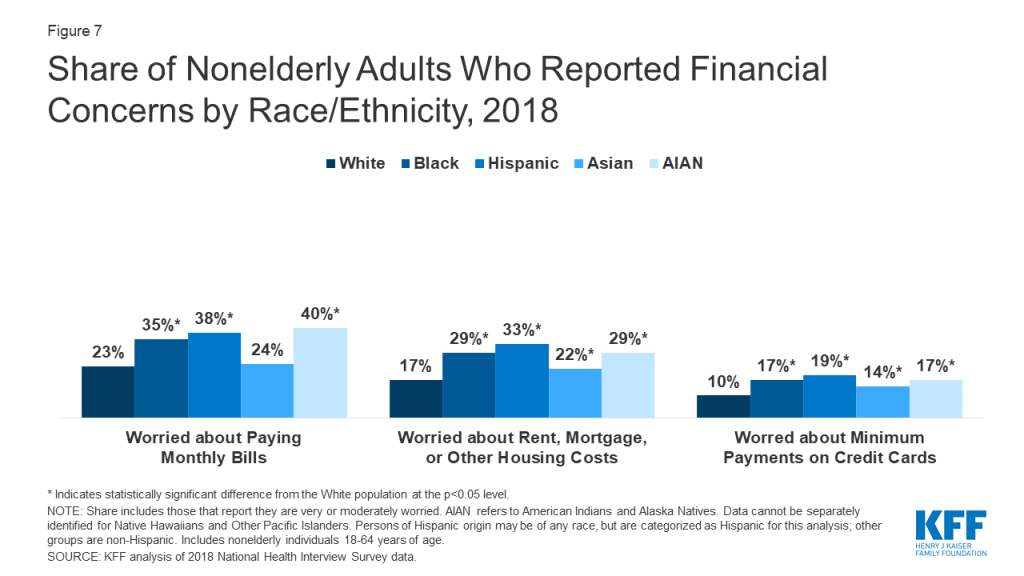

Communities of color face increased financial and health risks associated with COVID-19 due to economic and social circumstances. Social distancing policies required to address COVID-19 have led many businesses to cut hours, cease operations, or close altogether. People who work in certain industries, such as restaurant, hospitality, retail, and other service industries, are particularly at risk for loss of income. Those who maintain jobs amid the COVID-19 outbreak, such as grocery store workers and delivery drivers, are at increased risk of contracting coronavirus since they remain exposed to other individuals. Nearly a quarter of Blacks and Hispanics (24%) are employed in service industries compared to 16% of Whites, putting them at increased risk for job loss or loss of income or for exposure if they maintain their jobs.5 Groups of color also may have more limited ability to absorb income declines due to more limited incomes. Over a quarter of Blacks, Hispanics, and AIANs are low-wage workers, compared to less than 17% of Whites,6 and groups of color are more likely to have income below poverty compared to Whites (Figure 6). Reflecting their more limited incomes, prior to COVID-19, groups of color were more likely than Whites to report a range of financial concerns including being very or moderately worried about paying monthly bills; rent, mortgage, or other housing costs; and minimum payments on credit cards (Figure 7). They also are more likely to experience food insecurity.7

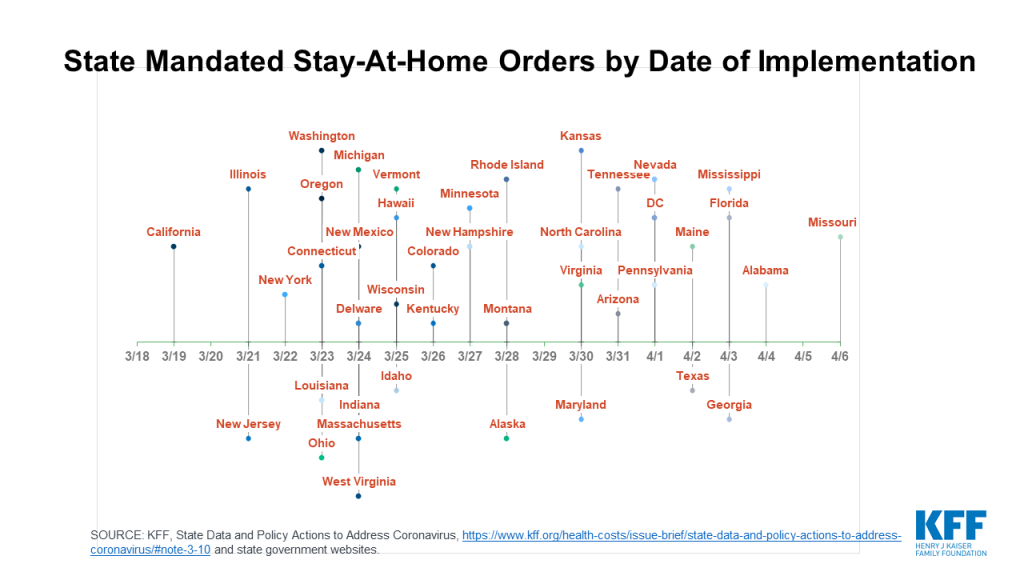

People of color are more likely to live in locations and housing situations that put them at increased risk of infection from coronavirus. The virus can spread quickly in densely populated urban areas, as evidenced by the rapid outbreak in New York City. Individuals in crowded living arrangements and/or multi-family dwellings also are likely at higher risk for exposure to the disease. Data also show that people of color make up over half (56%) of the population in urban counties, while Whites account for the majority in suburban (68%) and rural (79%) counties.8 Roughly four in ten Blacks (41%), Hispanics (38%), and Asians (38%) indicate that the area surrounding their residence includes multiunit residential buildings compared to 23% of Whites.9 Although much of the initial outbreak has been concentrated in more urban areas, it is anticipated that the disease will affect all areas of the country. Variation in timing of implementation of social distancing policies such as stay-at home-orders may also impact risk of infection across areas.

Looking Ahead

Early data suggest COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting groups of color. For example, in the District of Columbia, Blacks make up 45% of the total population, but accounted for 29% of confirmed cases and 59% of deaths as of April 6, 2020. In Louisiana, Blacks make up 32% of the total state population, but accounted for over 70% of COVID-19 deaths as of April 6, 2020. Data from Illinois show that groups of color accounted for 48% of confirmed cases and 56% of deaths as of April 6, 2020, while only making up 39% of the total state population. In North Carolina, Blacks make up 21% total state population, but accounted for 37% confirmed cases as of April 6, 2020. In Michigan, where Blacks make up 14% of the total state population, they accounted for 33% of confirmed cases and 41% of deaths as of April 6, 2020. Moreover, survey data find that Latinos are more likely than Americans overall to see COVID-19 as a major threat to health and finances.

The federal government and states have taken steps to mitigate the health and financial challenges stemming from the COVID-19 outbreak, but access to relief varies and some individuals will continue to face health and financial difficulties. Congress has passed a series of legislation to respond to COVID-19 that provides new resources to support access to health care and economic relief. States also are taking action to enhance access to health coverage and services through Medicaid and more broadly. However, individuals may not have equal access to relief and some individuals may continue to face health and economic challenges. For example, uninsured individuals may continue to face challenges accessing care or paying costs associated with treatment services. Moreover, some individuals, including some immigrant and mixed immigration status families and lower-income individuals who do not file tax returns, may not qualify for or may face challenges accessing economic relief. Further, recent experiences suggest that immigrants may be fearful of accessing health coverage and other assistance programs and/or health care due amid the current immigration policy environment and due to recent changes to public charge policy.

Comprehensive data by race and ethnicity will be key for understanding the impacts of COVID-19 across communities and on health and economic disparities going forward. Data by race and ethnicity will also be important for understanding the extent to which there are disparities in access to and receipt of health and economic relief. Together these data can help shape and target response and relief efforts. Although some states and localities are reporting data by race and ethnicity, as of early April, CDC was not reporting data by race and ethnicity and these data were not available widely across states. There are challenges to collecting and reporting these data, including determining standardized reporting categories and having to rely on self-reported and/or observational responses to collect these data. Self-reported data can provide for greater data accuracy, but may be subject to high non-response rates, while observational data may be prone to errors.10 CDC requests racial and ethnic data on its case reporting form for coronavirus, but had not indicated plans to expand reporting of these data as of early April.

Endnotes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “People Who Are at Higher Risk for Severe Illness,” April 2, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html. ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga and Kendal Orgera, Key Facts on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity, (Washington, DC, KFF, November 2019), https://modern.kff.org/report-section/key-facts-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity-health-status/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Remarks by President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Members of the Coronavirus Task Force in Press Briefing,” The White House, April 3, 2020, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-vice-president-pence-members-coronavirus-task-force-press-briefing-18/. ↩︎

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Report 1082, Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2018, October 2019, https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2018/home.htm. ↩︎

- Pending KFF analysis. ↩︎

- US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Key Statistics & Graphic: Food Insecurity by Household Characteristics, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx. ↩︎

- Kim Parker, et al., “What Unites and Divides Urban, Suburban and Rural Communities: 1. Demographic and economic trends in urban, suburban and rural communities,” Pew Research Center, May 2018, https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/05/22/demographic-and-economic-trends-in-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities/. ↩︎

- KFF analysis of 2017 American Housing Survey data, https://www.census.gov/data/data-tools/ahs-table-creator.html. ↩︎

- Eliminating Health Disparities: Measurement and Data Needs: Chapter 4: DHHS Collection of Data on Race, Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Position, and Acculturation and Language Use, p.67, https://www.nap.edu/read/10979/chapter/6#67. ↩︎