Several COVID-19 vaccines are now in phase 3 trials, and $10 billion in government money has been invested in the research, development, manufacturing, and distribution of vaccines. As part of this effort, the federal government has paid in advance for hundreds of millions of doses of multiple COVID-19 vaccines and, in some cases, has the option to purchase more. These government-purchased doses will be distributed for free to providers who will then administer the vaccine(s) under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) COVID-19 Vaccination Program.1 Once distributed, individuals will be able to get COVID-19 vaccine(s) without having to pay any cost sharing, due, in part, to changes made by Congress and CMS to the laws and regulations that typically govern insurance coverage for vaccines. The laws and regulations in place for other vaccines vary by program and type of insurance coverage—with some people qualifying for all CDC recommended vaccines without cost sharing, while others may either face cost sharing or gaps in coverage. As part of any campaign to encourage COVID-19 vaccinations, it will be important to make sure patients realize that access and affordability challenges they may have faced for other vaccines should not be a problem for the COVID-19 vaccine.

This brief explains how vaccines are covered and paid for through government programs and different types of insurance, including information on specific policies put into place for a COVID-19 vaccine. We describe vaccine coverage, patient cost sharing, and pricing in Medicare; private health insurance; the Vaccines for Children Program (VFC); Medicaid; Section 317 of the Public Health Services Act, which is the federal program that provides vaccines for uninsured adults; and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Our brief also includes background information on how the CDC develops vaccine recommendations, since many of the federal vaccine coverage requirements currently in place are tied to those recommendations. The brief also includes three tables. Table 1 provides the price per regimen of vaccines that the U.S. government has already purchased. Table 2 summarizes how vaccine prices are set in each program or type of insurance, and Table 3 compares vaccine list prices with prices paid by Vaccines for Children program and Section 317, the Veterans Administration, as well as prices paid by Medicare Part B and Medicare Part D (not accounting for rebates).

Box 1: Background on CDC’s Vaccine Recommendations

Both childhood and adult vaccines play a key role in public health both by preventing individuals from becoming sick and, for some vaccines, by protecting the larger community through generating population immunity. The CDC, the federal government’s public health agency, plays a large role in making vaccine recommendations for children and adults that then influence insurance coverage for vaccines along with other public health requirements, such as local school vaccine requirements.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is a federal advisory committee that develops recommendations on how to use vaccines to control disease in the United States, taking into account “consideration of disease epidemiology and burden of disease, vaccine safety, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, the quality of evidence reviewed, economic analyses, and implementation issues.” ACIP’s recommendations are reviewed by the CDC Director and, if adopted, are published as official CDC/Department of Health and Human Services recommendations in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Statutory requirements for vaccine coverage are often tied to ACIP’s recommendations.

ACIP makes vaccine recommendations for both children and adults. In cases where multiple manufacturers make a vaccine for a given disease, ACIP typically does not recommend one manufacturer’s vaccine over another, but there are exceptions. For example, the recombinant zoster vaccine (sold under the brand name Shingrix) was recommended preferentially over the zoster vaccine live (sold under the brand name Zostavax).

Medicare

Medicare covers vaccines for more than 60 million people ages 65 and older and younger adults with long-term disabilities under both Part B (which covers primarily outpatient care, including injected or infused drugs delivered in physician offices) and Part D (which covers retail prescription drugs). This separation of coverage for vaccines under Medicare is due to the fact that there were statutory requirements for coverage of a small number of vaccines under Part B before the 2006 start of the of the Part D benefit, which is delivered through prescription drug plans that contract with Medicare. Vaccines previously covered under Part B remain covered through that part of Medicare, while others are covered under Part D.

Vaccines for influenza, pneumococcal disease, and hepatitis B (for patients at high or intermediate risk), and vaccines needed to treat an injury or exposure to disease are covered under Part B. All other commercially available vaccines needed to prevent illness are covered under Medicare Part D. Vaccine pricing, provider reimbursement, and patient out-of-pocket costs vary under both parts of Medicare.

Cost to patients

For the influenza, pneumococcal pneumonia, and hepatitis B vaccines covered under Medicare Part B, patients currently face no cost sharing for either the vaccine itself or its administration. For other Part B covered drugs and services, Medicare covers 80% of the cost, and beneficiaries are responsible for the remaining 20%. Cost sharing for the COVID-19 vaccine is discussed below. The majority of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare have supplemental insurance—such as Medigap, employer sponsored coverage, or Medicaid—that covers some or all of the coinsurance, but 6 million beneficiaries do not have supplemental insurance to cover these costs. The 24 million beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans are also responsible for cost-sharing requirements, which vary across plans.

As mentioned above, all commercially available vaccines that are not covered under Part B are required to be covered under Part D. Unlike Part B, Part D plans have flexibility to determine how much enrollees will be required to pay for any given on-formulary drug, including vaccines. (Part D enrollees who receive low-income subsidies (LIS) generally pay relatively low amounts for vaccines and other covered drugs.) For example, in 2018, average cost sharing by non-LIS enrollees for a dose of Shingrix, the shingles vaccine, was $57, while average cost sharing for Adacel (Tdap) was $24. Under Part D, cost sharing can take the form of flat dollar copayments or coinsurance (i.e., a percentage of list price). Patients do not pay separate cost-sharing amounts for the vaccine and its administration.

Vaccine price

For the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines covered under Part B, Medicare reimbursement is set at 95% of the Average Wholesale Price (AWP), except when furnished in a hospital outpatient setting, in which case reimbursement is based on reasonable cost. Medicare publishes an annual list of payment allowance limits for the influenza vaccines available in a given season. AWP is a publicly available, suggested price for sales of a drug by a wholesaler to a pharmacy or other provider. It is akin to a sticker price and used as a starting point for negotiation for payments to retail pharmacies. For other Part B covered drugs, reimbursement is 106% of the Average Sales Price (ASP). ASP is the average price to all non-federal purchasers in the United States and includes volume discounts, prompt pay discounts, cash discounts, free goods that are contingent on any purchase requirement, chargebacks (other than chargebacks for 340B discounts), and rebates (other than rebates under the Medicaid drug rebate program). The discounts and rebates factored into ASP are not accounted for in AWP.

Because the Part D benefit is administered by private drug plans, which are sponsored by private insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), vaccine pricing and reimbursement will vary depending on negotiations between manufacturers and plans. This can lead to different prices paid for the same vaccine by different Part D plan sponsors, and different cost sharing among enrollees across Part D plans for the same vaccine. The size of rebates paid by manufacturers to PBMs and plans will depend in part on the competitive dynamics for each vaccine and how price sensitive patients are to higher out-of-pocket costs if a vaccine is placed on a higher tier.

COVID-19 vaccine requirements

Under the CARES Act and an accompanying interim final rule2 , Medicare beneficiaries will have coverage for COVID-19 vaccines through Medicare Part B with no cost sharing (rather than the typical 20% coinsurance). This coverage applies whether the vaccine receives FDA authorization through an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) or is licensed under a Biologics License Application (BLA). Covering a COVID-19 vaccine under Part B rather than Part D will ensure broader coverage for the vaccine under Medicare since not all beneficiaries are enrolled in a Part D plan.

While Medicare will not pay for the initial doses of the COVID-19 vaccine already purchased by the government, if eventually the vaccine is reimbursed by Medicare, it will be reimbursed at 95% of AWP.3 That is the same formula used for influenza and pneumococcal vaccines.

Private Health Insurance

About 55% of people in the U.S. have private health insurance, and the vast majority of them are covered through employer-sponsored insurance. All non-grandfathered employer-sponsored health plans and individually purchased insurance from the Marketplaces are subject to certain coverage requirements and standards included in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). ACA-compliant individual coverage purchased off the marketplaces are subject to those requirements as well. However, the Trump Administration has expanded access to short-term plans, which are not subject to any federal coverage standards.

Cost to patients

Individual and employer-sponsored private health plans subject to the ACA’s preventive services coverage standards must provide coverage for individuals to receive vaccines that ACIP recommends without cost sharing. When a new vaccine is added to ACIP’s recommendations, plans must update their coverage once a new plan year starts following one year after the date when the CDC adopts that recommendation.4 Requirements specific to the COVID-19 vaccine are described below. Coverage for recommended vaccines is provided without cost sharing even for beneficiaries who have not reached their deductible. Short-term plans do not have to meet such standards and can require that beneficiaries pay cost sharing for vaccines or can exclude recommended vaccines from coverage altogether.

Vaccine price

There are no federal limits or rules regarding the price of vaccines or other prescription drugs in the private market. However, the inclusion of economic analysis in the development of ACIP recommendations may help to tamp down on prices for vaccines as compared to other medicines where there is no equivalent federal use of such analysis.

As with other medicines, rebates and other price concessions from drug manufacturers lower the net price of vaccines in many cases, although the size of those price concessions vary based on the competitive dynamics for each pharmaceutical product, along with other factors. Rebates and other price concessions are not made public, so we do not have data on the size of rebates for vaccines, how much the prices private plans pay for vaccines and how the prices vary from the list prices included in Table 3. It is possible that requirements for plans to cover vaccines without cost sharing may limit their ability to negotiate large rebates for vaccines.

COVID-19 vaccine requirements

The CARES Act requires that employer-sponsored and individual health plans subject to the ACA’s preventive services standards cover a coronavirus vaccine without cost sharing 15 days after it is recommended by ACIP.5 This will ensure that a coronavirus vaccine is covered by private insurance more quickly than the longer timeframe typically required for private health plans to incorporate a new ACIP recommendation. The guarantee is tied to the ACA provision requiring private insurers to cover vaccines, so it could be voided if the Supreme Court overturns the ACA.

During the public health emergency, private health insurance plans will be required to cover all the costs of a COVID-19 vaccine even if an out-of-network provider administers it.6 The Trump Administration’s interim final rule states that Medicare’s payment rate will be considered a reasonable rate for coronavirus preventive services, including administration of a COVID-19 vaccine.7 Additionally, vaccine providers may not seek any reimbursement, including through balance billing, from a vaccine recipient.8

Vaccines for Children Program

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program is a federal entitlement for eligible children created by Congress in 1993 in response to a measles outbreak that extended from 1989 through 1991. In 2020, the program had a budget of about $4.8 billion. Under this program, the CDC purchases vaccines directly from manufacturers and distributes them to grantees (i.e. state health departments and some local health agencies). Those partners then distribute the vaccines at no charge to private physicians’ offices and public health clinics registered as VFC providers. Vaccines recommended by ACIP are included in the VFC program. More than half of young children and one-third of adolescents in the United States are eligible to receive vaccinations through this program.9

Children under age 19 are eligible for the VFC program if they are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, or American Indian or Alaska Native. Children can also qualify if their insurance has a cap on vaccine coverage that the child has surpassed or if their insurance does not cover all or certain vaccines.10 Those types of limitations on vaccine coverage are not permitted under standards established by the ACA,11 but some grandfathered plans or short-term plans may include these limitations on vaccine coverage.

Cost to patients

Children get vaccines for free through the VFC program, but participating health care providers can charge for other services including administering vaccines and office visits. The fees for vaccine administration are limited by regulation, and children cannot be denied a vaccine because they cannot afford the administration fee itself, but the VFC program allows providers to refuse to see qualifying children if the provider will not be paid for the office visit. For children with Medicaid, the office visit and vaccine administration are covered by Medicaid with no cost sharing.12 Children who are uninsured may be eligible for free or reduced cost office visits and vaccine administration through a community health center. Additional cost sharing protections for the COVID-19 vaccine are discussed below.

Vaccine price

The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is authorized by statute to negotiate a discounted price for vaccines purchased under the VFC program.13 There is also an inflation-adjusted price cap for vaccines that were available in 1993 but no cap for newer vaccines. States can purchase additional vaccines at the VFC price for children who are not eligible for the program. Table 3 compares VFC prices for vaccines to the list prices and the prices paid by other federal programs. On average, the price the CDC pays for vaccines purchased through the VFC program is about 30% less than the list price. The level of discount off of the list price varies substantially and ranges from 15% below list price to 72% below list price.

When there are multiple manufacturers of a vaccine, the Secretary of HHS is authorized to contract with more than one manufacturer. This can help avoid shortages if one provider experiences problems in the supply chain. To help ensure sufficient supply, the statute also requires the Secretary to purchase six months of additional vaccine supply beyond what would otherwise be required.14

COVID-19 vaccine requirements

The CDC will determine if COVID-19 vaccine(s) will be included in the VFC program.15 If they are included, then Medicaid will cover the administration fee for Medicaid-eligible children.16 COVID-19 vaccine administration costs for uninsured children can be reimbursed using the $175 billion provider relief fund created by the CARES Act, which the Trump Administration has stated it will use to cover vaccine-related administration costs for people who are uninsured. As of November 10, 2020, about $30 billion remained in that fund. However, it is unclear how well that system will work given that there have been challenges with a similar system for reimbursing for treatment for uninsured COVID-19 patients. It also not clear when there will be a vaccine available to children. The Food and Drug Administration said on October 22 that they do not know yet if the vaccine candidate(s) authorized or approved will be recommended for children.

Medicaid and CHIP

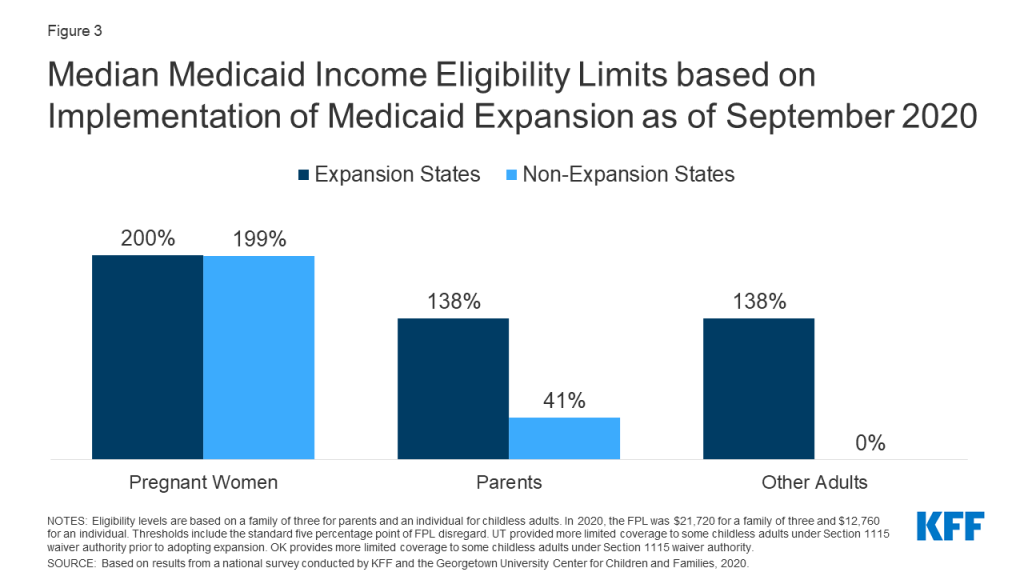

Preliminary data for July 2020 show that Medicaid and CHIP provide health insurance coverage to 75.5 million low-income Americans. Medicaid coverage for vaccines varies based on age, eligibility pathway, and state. Vaccines are an optional benefit for certain adult populations, including low-income parent/caretakers, pregnant women, and persons who are eligible based on old age or a disability. For adults enrolled under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and other populations for whom the state elects to provide an “alternative benefit plan,” their benefits are subject to certain requirements in the ACA, including coverage of ACIP-recommended vaccines with no cost sharing.17 There are separate coverage requirements for the COVID-19 vaccine during the time that states are receiving enhanced federal matching funds under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, and those are discussed below.

All states provide some vaccine coverage for adults enrolled in Medicaid who are not covered as part of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, but as of 2019, only about half of states covered all ACIP-recommended vaccines.18 The ACA provides an incentive to states to cover all recommended vaccines without cost sharing for adults by providing a 1 percent increase in a state’s Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for vaccine spending, and at least 12 states have implemented this option.19 States can choose to cover a vaccine as a pregnancy-related service only and not for other adults who do not receive an “alternative benefit plan.” Otherwise, states that choose to cover vaccines must provide that coverage for all low-income parent/caretakers, people eligible based on old age or disability, and pregnant women eligible for full state plan benefits.20

Medicaid-eligible children under 19—including those covered under a Medicaid-expansion Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) program—are covered under the Vaccines for Children Program, where they receive vaccinations at no cost. Children covered by separate CHIP programs are not covered by Vaccines for Children, but age-appropriate vaccines are a required CHIP benefit.21 States must purchase vaccines for these children using CHIP funds, not Vaccines for Children funding.22 ,23

Cost to patients

Federal Medicaid rules allow states to impose nominal cost sharing, but only for specific populations, and providers cannot refuse to provide a vaccine to a patient if they cannot pay their share of costs.24 Adults in the Medicaid expansion population, and other populations for whom the state elects to provide an “alternative benefit plan,” must receive preventive vaccines with no cost sharing. Other Medicaid populations generally exempt from cost sharing include most children under 18, most pregnant women, most children in foster care, people in institutions with a share of cost, people in hospice, and people receiving Indian health care provider services; other adults may be subject to nominal charges at state option.25 Children under 19 covered by Medicaid or CHIP receive recommended vaccines without cost sharing, including the office visit and administration.26 ,27 Young adults covered by Medicaid aged 19-20 are eligible for the Early, Periodic, Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, which includes vaccine coverage, but they may face cost sharing at state option if they are not enrolled in an alternative benefit plan.

Vaccine price

Vaccines are excluded from the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP). The MDRP requires Medicaid programs to cover all FDA-approved drugs from participating manufacturers in exchange for rebates to Medicaid to offset the cost of prescription drugs.28 The program ensures Medicaid pays among the lowest prices for drugs and provides access to medications for enrollees. Excluding vaccines from the MDRP has both cost and coverage implications, as states are not required to cover all vaccines and do not receive rebates, which are a significant offset to Medicaid pharmacy spending.

States reimburse providers for administering vaccines, and reimbursement varies widely across states. States generally set payment rates for provider reimbursement through fee schedules and have broad flexibility within federal guidelines to determine payment rates.29 Payment rates for vaccines provided through fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid may differ from those provided through managed care.30 ,31 Most states’ FFS fee schedules make a payment for vaccine administration in addition to reimbursing for the vaccine, and some states may reimburse for an office visit fee.32 Due to this wide state variation, there is no one price paid by Medicaid; for example, one study found that, as of 2019, FFS reimbursement for an HPV vaccine ranged from $5.27 in Missouri to $491.38 in Mississippi.33 It also found that on average, Medicaid FFS reimbursed providers an amount greater than the price paid by the CDC for vaccines that it purchases and also sometimes greater than manufacturer list price of a vaccine: for example, median FFS reimbursement for Hepatitis B vaccines ranged from 188% to 251% of the price paid by the CDC for vaccines and from 113% to 153% of list price.34

COVID-19 vaccine requirements

Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, coverage of testing and treatment for COVID-19, including vaccines, is required with no cost sharing in order for states to access temporary enhanced federal funding for Medicaid.35 All states have taken up this enhanced federal funding and are therefore subject to these requirements. Under these rules, states also must compensate Medicaid providers for an administration fee or office visit, even if the vaccine is provided free of charge.36 To receive enhanced federal funding, states must also provide continuous coverage for individuals enrolled as of March 18, 2020 through the end of the month in which the COVID-19 public health emergency ends. Recent CMS guidance has reinterpreted the continuous coverage requirement to allow some changes between eligibility categories, but beneficiaries may not lose access to COVID-19 testing and treatment services if this was included in their original coverage on or after March 18, 2020.37

The enhanced federal funding and COVID-19 vaccine coverage requirements are tied to states’ receipt of enhanced federal matching funds during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE) declaration and only last through the end of the quarter in which the PHE ends.38 This means requirements to cover a coronavirus vaccine at no cost to enrollees will expire if the PHE is not renewed. Regular Medicaid rules regarding coverage of and cost sharing for vaccines (described above) will apply after the end of the PHE. HHS could continue to extend the PHE or Congress could pass additional legislation extending maintenance of effort requirements for COVID-19 vaccine coverage and enhanced federal funding or otherwise addressing Medicaid COVID-19 vaccine coverage.

Section 317 of the Public Health Services Act: Vaccines for Uninsured Adults

There is no federal entitlement program for uninsured adults to receive free vaccines similar to the VFC program for children. However, the federal government purchases a limited number of vaccines directly for uninsured and other qualifying adults through funding that comes from Section 317 of the Public Health Services Act. Section 317 is also used to provide funding to support public health infrastructure in the United States at the federal and state and local levels, and more than three-quarters of the program’s total funding is used for that purpose. Section 317 is a discretionary program, and its total budget in 2020 was about $616 million.39 Some states supplement the federal funding they get from Section 317 with state funds in order to reach more people.

After the ACA was passed, the CDC updated the eligibility criteria for adults to get vaccines through Section 317.40 As of 2012, adults are eligible for vaccines through Section 317 if they are uninsured, do not have coverage for vaccines, or are being vaccinated as part of a public health response such as a mass vaccination campaign.41

Cost to patients

Uninsured adults may be able to get free vaccines from their state or local health department or a community health center through Section 317. Because Section 317 is a discretionary program and its budget for each year is fixed, federal funding for vaccines for uninsured adults does not increase automatically if the number of uninsured increases or if the cost of vaccines increases. The limited amount of funding available for vaccines purchased through Section 317 may be one factor contributing to lower influenza vaccination rates for uninsured adults. While about 40% of adults 18-64 with private or public insurance got the flu vaccine in 2018, just 16% of uninsured adults did so.

Vaccine price

As under the VFC program, the CDC negotiates prices for vaccines purchased through Section 317. Table 3 lists the prices the CDC pays for vaccines for adults purchased through Section 317. On average, the CDC price is about 40% less than the list price. The level of discount off of the list price varies substantially and ranges from 24% below list price to 59% below list price. Local entities providing vaccines under Section 317 may also have other sources of funding they use to pay for vaccines for people who are uninsured and can purchase additional doses at the Section 317 price.42 They also may be able to obtain free or discounted vaccines from pharmaceutical manufacturers’ patient assistance programs.

COVID-19 vaccine requirements

Providers that participate in the CDC COVID-19 Vaccination Program contractually agree to administer a COVID-19 vaccine regardless of an individual’s ability to pay and regardless of their coverage status.43 This means that people who are uninsured should be able to get the COVID-19 vaccine from a wider range of providers than just those that participate in Section 317. Providers that administer the COVID-19 vaccine to the uninsured will be reimbursed for vaccine administration costs through the $175 billion provider relief fund created by the CARES Act. The Trump Administration recently clarified that this fund will also be used to reimburse providers for people who have limited Medicaid benefits that do not include vaccine coverage, such as individuals who only have coverage for COVID-19 testing, or family planning services and supplies.44 As of November 10, 2020, about $30 billion remained in the provider relief fund, and it is also being used to pay for COVID-19 treatment costs for people who are uninsured, as well as broader provider relief related to the pandemic. Once the government has distributed the initial doses of COVID-19 vaccine(s), more funding may be needed through Section 317 or other programs to ensure there are sufficient vaccine doses for everyone who is uninsured if the vaccine is needed on an ongoing basis.

Additional outreach from trusted sources may also be needed to reach people are uninsured since they are less likely to have a usual source of care than those who are insured. It will be important for people who are uninsured to understand both the importance of getting a vaccine once one is available to them and that the vaccine will be available at no cost to them. Many of the COVID-19 vaccines in clinical trials require two doses, which will increase the importance of appropriate education and outreach to people who are uninsured.

Department of Veterans Affairs

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is an integrated health care delivery system serving qualifying veterans. The VHA estimates that in 2020 it will provide care to more than 6 million patients.45 Eligibility for health care through the VA is based primarily on veteran status from military service. Veterans generally must also meet minimum service requirements; however, exceptions are made for certain circumstances, including discharge due to service-connected disabilities.46

Cost to patients

The VA health system does not charge cost sharing for preventive care, including vaccinations.47

Vaccine price

In order to participate in Medicaid and Medicare Part B, drug manufacturers must sell their medicines at a discount to the VA, along with the other three of the “Big Four” government agencies (U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Public Health Service, and U.S. Coast Guard). The VA is in some cases able to negotiate even steeper discounts in return for preferential placement on its drug formulary. The “Big Four” price is the lower of two prices determined by formula:

- Federal Ceiling Price: A minimum 24% discount off the “non-Federal Average Manufacturer Price” (non-FAMP) plus additional discounts if non-FAMP rises faster than inflation. The non-FAMP is the average price paid to manufacturers by wholesalers for drugs distributed to non-federal purchasers. The price takes into account any price reductions given to wholesalers, but does not account for rebates to PBMs or other third parties. A statutory formula requires additional discounts, if necessary, to prevent the federal ceiling price from rising faster than the rate of inflation.

- Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) Price: The VA negotiates FSS prices with manufacturers on the basis of the prices that manufacturers charge their most-favored commercial customers under similar terms and conditions. During multiyear contracts, the FSS price may not increase faster than inflation.

These statutory discounts result in an average discount of about 40% off of the list price, with discounts ranging from 24% to 63% (Table 3).

COVID-19 vaccine requirements

Under current regulations, the VA does not require cost sharing for “an outpatient visit solely consisting of preventive screening and vaccinations (e.g., influenza vaccination, pneumococcal vaccination).”48 There are currently no VA-specific requirements related to a COVID-19 vaccine.

Implications

The current focus on a COVID-19 vaccine has fueled interest in issues related to vaccine coverage, pricing and cost sharing. As described in this brief, vaccines for children and adults are provided through various programs and types of insurance, each with different rules for vaccines already on the market. This means that many changes to insurance requirements were needed in order to ensure access to a COVID-19 vaccine with no cost sharing once a vaccine is approved and available. For other vaccines, there are no universal standards to ensure that ACIP-recommended vaccines are available to everyone with no cost for either the vaccine or its administration.

There is also no one system for vaccine pricing. HHS negotiates the price of vaccines directly with manufacturers and purchases vaccines through the Vaccines for Children Program and Section 317. Other vaccine prices are largely set by a mix of statutory formulas, private negotiations, and state reimbursement decisions in the case of Medicaid.

The federal government has already paid for several hundred million doses of multiple COVID-19 vaccines through Operation Warp Speed, even before clinical trials have been completed. Under the terms of Operation Warp Speed, the federal government has the option to purchase hundreds of millions of additional doses. It remains unclear how many additional doses of COVID-19 vaccines may eventually be needed, by when, and how long immunity will last under a COVID-19 vaccine. If, in the future, the COVID-19 vaccine becomes a regular, annual vaccine, it is expected that it would eventually be covered through the same programs and types of insurance that are currently used to pay for other vaccines. If concerns arise about the eventual cost of COVID-19 vaccine(s) or other vaccines to federal and state governments and private payers, policymakers may look to rules that already govern vaccine pricing and reimbursement in different markets to leverage the government’s buying power.