Summary

Except for during surges in COVID-19 cases, cancer is the second leading cause of death in the U.S in both men and women nationally, with the majority of cancer related-deaths being due to breast, prostate, lung, and colon cancers. Racial disparities in cancer incidence and outcomes are well-documented, with research showing that they are driven by a combination of structural, economic, and socioenvironmental inequities that are rooted in racism and discrimination, as well as genetic and hereditary factors that may be influenced by the environment. Despite significant advancements and improvements in cancer outcomes and treatment over time, disparities persist.

This brief provides an overview of recent data on cancer incidence and mortality, risk factors, screening, treatment, and outcomes by race and ethnicity. It is based on KFF analysis of United States Cancer Statistics cancer incidence and mortality data (latest available data as of 2018), 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System cancer screening data, and published research. Although this brief focuses on racial disparities in cancer, disparities also occur across other dimensions, including socioeconomic status, exposure to risk factors, geographic location, and receipt of preventive measures.

Overall cancer incidence rates decreased for all racial and ethnic groups between 2013 and 2018, with the largest decreases among American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) and Black people. This decrease eliminated a disparity in overall cancer incidence for Black people, although they still have the highest incidence rate for some cancer types. Black people have higher new cancer rates for prostate, and colon and rectum cancer compared to other groups and one of the highest rates of new breast cancers. Moreover, across all cancers and for each cancer type, there are differences within racial and ethnic groups, such as by gender, country of origin, and geographic location.

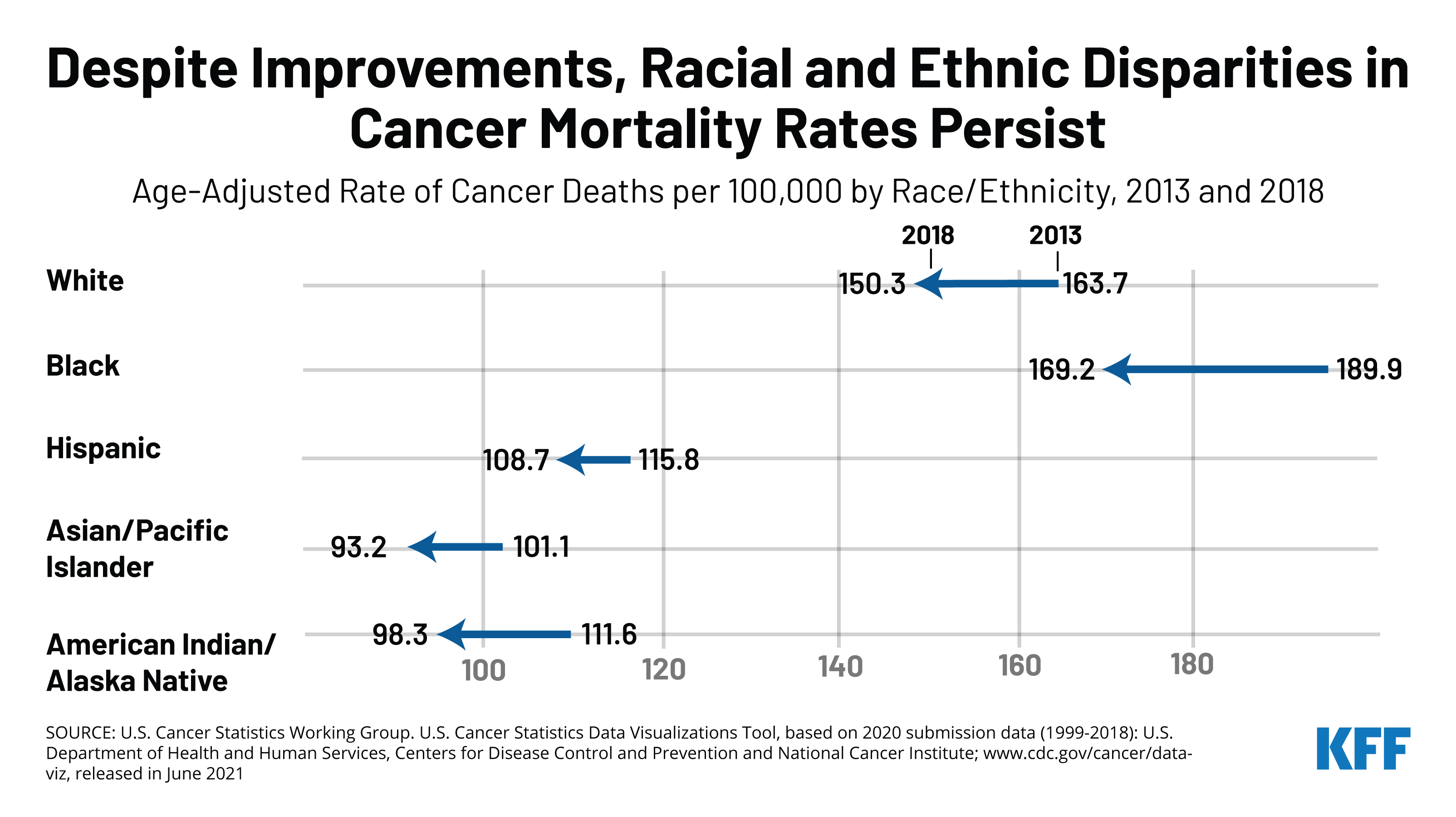

Cancer mortality rates have also declined across all racial and ethnic groups, with the largest decrease among Black people, but Black people continued to have the highest cancer mortality rate in 2018. As is the case for cancer incidence rates, racial and ethnic patterns of cancer mortality vary by cancer type. Black people have the highest mortality rate for most leading cancer types, including female breast, prostate, and colon and rectum cancer. The higher mortality rate among Black people partly reflects a later stage of disease at diagnosis among Black patients, although Black patients additionally have lower stage-specific survival for most cancer types.

Research shows that the overall rate of cancer screening is lower among Black, Hispanic, Asian, and AIAN populations compared to their White counterparts. However, screening patterns vary across screening types, and people of color are more likely than White people to receive certain types of cancer screening. Data suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to decreases or delays in cancer screening, which may have exacerbated disparities in cancer screening.

Despite mixed findings regarding cancer screening disparities, research suggests people of color receive later stage diagnoses for some types of cancer compared to their White counterparts. For certain cancers, disparities in stage of diagnosis despite comparable screening rates may be related to screening guidelines not accounting for earlier onset and increased age-specific cancer incidence for different groups, as well as disparities in quality of screening techniques and delays in diagnostic evaluation. Racial disparities in cancer care and treatment have also been identified, particularly for diagnostic and treatment delays, which contribute to worse survival outcomes.

Research suggests that cancer disparities are driven by a combination of inequities within and beyond the health system that are rooted in racism and discrimination. People of color are more likely than their White counterparts to be uninsured and to face other barriers to accessing health care that may limit access to cancer screening, care, and treatment. Beyond health coverage and access to care, discrimination and bias within the health care system and disparities in exposure to risk factors, due largely to underlying social and economic inequities, also drive cancer disparities. While socioeconomic and health care access factors are primary drivers of cancer disparities, research also suggests that hereditary risk and genetic determinants for specific cancer subtypes may explain a portion of disparities. Underrepresentation of people of color in the development of current screening guidelines and in oncology cancer trials may also contribute to disparities.

Overall, the data suggest that continued efforts within and beyond the health care system will be important to reduce ongoing racial disparities in cancer. Within the health care system, these may include efforts to reduce gaps in health insurance, increase access to care, and eliminate discrimination and bias in care and treatment. Beyond the health care system, it will also be important to address broader social and economic factors, including exposure to environmental risks and disparities in behavioral risks. Furthermore, there are ongoing discussions about reevaluating the implications of current cancer screening guidelines for disparities and whether to adjust guidelines or cancer screening approaches to account for higher prevalence and risk and earlier age of onset for certain cancers among different communities. Moving forward, increasing diversity among oncology clinical trials and within the health care workforce also will be important for addressing disparities in cancer care and treatment and ensuring that all people benefit from continued advancements in cancer treatment.

Cancer Incidence by Race and Ethnicity

Overall cancer incidence rates decreased for all racial and ethnic groups between 2013 and 2018, with the largest decreases among AIAN and Black people (Figure 1). This decrease eliminated a disparity in overall cancer incidence for Black people, who had the highest rate of new cancers in 2013 but had a similar cancer incidence rate as White people in 2018. Among the four leading types of cancer, rates of new lung and bronchus and colon and rectum cancer decreased across all racial and ethnic groups from 2013 to 2018. Rates of new prostate cancer cases decreased for Black, Hispanic, and AIAN people, while they remained fairly stable for White and Asian and Pacific Islander people over the period. The decreases narrowed disparities in colon and rectum and prostate cancer incidence rates for Black people over the period. New female breast cancer rates also decreased for AIAN and Black people, while there were small increases in the breast cancer incidence rate for other groups.

Overall, White and Black people have the highest rates of new cancers. Within the U.S., there were over 1.7 million new cancer cases reported in 2018, or 436 new cancer cases for every 100,000 people. White people had the highest rate of new cancers at 437 per 100,000 people, followed by Black people at 427 per 100,000 people, while cancer incidence rates were lower among Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander, and AIAN people. Although Asian and Pacific Islander (API) men and women have the lowest overall cancer incidence and mortality, they have among the highest liver and stomach cancer rates, roughly double the rates for White people.

Patterns of cancer incidence by race and ethnicity vary across cancer types. Female breast, prostate, lung and bronchus, and colon and rectum cancers had the highest rates of new cancers in 2018. Although White or Black people had the highest incident rates across these cancer types, patterns of incidence by race and ethnicity varied by type (Figure 2):

- Female breast cancer. Like cancers overall, White people had the highest rate of new female breast cancers (128 per 100,000 females), followed by Black people (121 per 100,000 females). Other racial/ethnic groups had lower incidence rates, particularly AIAN people, whose new female breast cancer rate was roughly half the rate for White people at 65 per 100,000 females.

- Prostate cancer. Black people had the highest rate of new prostate cancers at 164 per 100,000 males, followed by White people at 99 per 100,000 males and Hispanic people at 80 per 100,000 males. Asian and Pacific Islander and AIAN people were substantially less likely to have a new prostate cancer case, as their rates were more than three times lower than the rate for Black people.

- Lung and bronchus cancer. Rates of new lung and bronchus cancer were similar for White and Black people at 55 and 54 per 100,000 people, respectively, while rates were lower for other groups and lowest for Hispanic people at 27 per 100,000.

- Colon and rectum cancer. Black people had the highest rate of new colon and rectum cancer (40 per 100,000 people), followed by White and Hispanic people, at 36 and 33 per 100,000, respectively. The lowest rate of new colon and rectum cancers was among AIAN people at 26 per 100,000 people.

Across all cancers and for each cancer type there are differences in incidence rates within racial and ethnic groups, such as by gender, geographic location, and country of origin. For example, overall cancer incidence rates were higher for men than women among White, Black, Hispanic, and AIAN people in 2018, while they were higher for women among Asian and Pacific Islander people. Black men have the highest rates of age-adjusted lung cancer incidence among all groups. In general, rural populations have higher incidence of preventable cancers and higher mortality compared to their urban counterparts, although cancer incidence is higher in urban areas for some types of cancer, such as breast and prostate cancer. Research further shows a similar pattern for people of color in rural areas, who generally have higher cancer incidence and mortality for preventable cancers compared to their urban counterparts. Other research has found that Black women in rural counties had higher incidence of regional cervical cancer than those in urban counties, and White women in rural counties had higher incidence than those in urban counties for cervical cancer at every stage, while there were no rural-urban differences among Hispanic women. Research also shows that, within racial and ethnic groups, there is wide variation in cancer incidence between U.S.-born and foreign-born people living in the U.S. For example, studies show that foreign-born Hispanic and Asian people have higher incidence of gastric cancer than their U.S. born counterparts, largely due to increased infection from H. pylori, which is endemic to multiple Latin American and Asian countries. However, compared to foreign-born Latino people, U.S.-born Latino people have higher rates of breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, and liver cancers, and U.S.-born Chinese and Filipina people have higher breast and colorectal cancer incidence compared to their foreign-born counterparts.

Cancer Mortality by Race and Ethnicity

Overall cancer mortality rates decreased for all racial and ethnic groups, with the largest decrease among Black people, but Black people continued to have the highest cancer mortality rate in 2018 (Figure 3). Between 2013 and 2018, the difference between the overall cancer mortality rate for Black and White people narrowed, but Black people remained at higher risk for cancer death. Among the leading four types of cancer death, mortality rates for female breast cancer decreased for White, Black, and Hispanic people and increased for Asian and Pacific Islander and AIAN people. Colon and rectum and lung and bronchus cancer mortality rates decreased across all racial and ethnic groups, while prostate cancer mortality rates decreased for Black and AIAN people but remained fairly stable for White and Asian and Pacific Islander people. Decreases over the period narrowed disparities in mortality for Black people for colon and rectum, lung and bronchus, and prostate cancer, although they remained at higher risk for dying from colon and rectum and prostate cancer compared to White people. The decreases largely eliminated the difference in lung and bronchus mortality rates between Black and White people, while the difference in breast cancer mortality rates remained largely stable.

Black people are at the highest risk for cancer death even though White people have the highest rate of new cancers. This increased mortality risk partly reflects a later stage of disease at diagnosis among Black patients, although Black patients additionally have lower stage-specific survival for most cancer types. In 2018, Black people had the highest cancer mortality rate at 169 per 100,000 people, followed by White people at 150 per 100,000 (Figure 4). Rates were lower for Hispanic, AIAN, and Asian and Pacific Islander people. As is the case for cancer incidence rates, racial and ethnic patterns of cancer mortality vary by cancer type:

- Female breast cancer. Black people had the highest rate of female breast cancer deaths (27 per 100,000 females) followed by White people (19 per 100,000 females), despite White people having the highest rate of new female breast cancers. Female breast cancer death rates for other groups were half or less than the rate for Black people.

- Prostate cancer. Consistent with having the highest incidence of prostate cancer, Black people also had the highest rate of prostate cancer deaths, at 37 per 100,000 males, more than twice as high as the rates for all other groups, which ranged from 9.2 per 100,000 males for Asian and Pacific Islander people to 17.7 per 100,000 males for White people.

- Lung and bronchus cancer. Like patterns in cancer incidence rates, Black and White people are at similar risk for lung and bronchus cancer death, with a mortality rate of 36 per 100,000 people for both groups. These rates are higher than rates for other groups, and more than double the rate for Hispanic people (15 per 100,000 people).

- Colon and rectum cancer. Racial/ethnic patterns of colon and rectum cancer mortality rates also were similar to incidence patterns with Black people having the highest colon and rectum cancer death rate (17 per 100,000 people), followed by White people at 13 per 100,000 people and a slightly lower rate for Hispanic people at 11 per 100,000 people. Asian and Pacific Islander people had the lowest rate of death due to colon and rectum cancer at 9 per 100,000 people.

As is the case for cancer incidence, across all cancers and for each cancer type there are differences in cancer mortality rates within racial and ethnic groups, such as by gender, country of origin, and geographic location. Across racial and ethnic groups, men have higher rates of cancer death compared to women. Notably, there exists variation in cancer mortality between U.S.-born and foreign-born Black people living in the U.S. For example, one study found that U.S.-born Black people experienced higher cancer mortality for cervical, lung and bronchus, colorectal, and prostate cancers compared to Black individuals from the Caribbean. Similarly, compared to foreign-born Latino people, U.S.-born Latino people have worse survival rates for breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, and liver cancers. In contrast, compared to foreign-born Asian people, U.S.-born Asian people experience lower mortality rates across multiple cancers, including breast, colon and rectum, and prostate cancers.

Cancer Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment by Race and Ethnicity

Research shows that the overall rate of cancer screening is lower among Black, Hispanic, Asian, and AIAN populations compared to their White counterparts, but people of color are more likely than White people to receive certain types of screening. Reasons for these variations in screening patterns across different groups are not well understood. Research suggests that outside of health insurance coverage and geographic differences, participation in cancer screening is related to multiple factors, such as provider recommendation, shared decision-making between patients and providers, perceptions of cancer screening, and gender differences in cancer screening behaviors, which may vary across communities.

- Mammograms. Since implementation of the Affordable Care Act coverage expansions, the share of people who have gone without a recent mammogram fell for some groups but did not change for other groups. Between 2012 (the latest year data are available prior to implementation of the ACA coverage expansions in 2014) and 2020, the share of people in the groups recommended for screening by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) who did not receive a recent mammogram fell for White, Black, and Hispanic people. There was no significant change for other groups. Hispanic people had the largest decrease, with the share falling by 11 percentage points from 32% to 21%, and Black people had a 7 percentage point decline from 22% to 15% (Figure 5). In contrast, White people had a smaller 2 percentage point decrease from 24% to 22%. The larger decrease for Hispanic people reversed a disparity and resulted in them being less likely than White people to go without a recent mammogram as of 2020 (21% vs. 22%). The share of Black people who did not receive a mammogram was already slightly lower than White people as of 2012 (22% vs. 24%), and this difference widened to 15% vs. 22% as of 2020. While this improvement likely, in part, reflects the implementation of focused interventions to decrease disparities in breast cancer screening, research also suggests that Black and Hispanic women are more likely than White women to overestimate their screening history. Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) people also were less likely than White people to go without a recent mammogram as of 2020, while Asian and AIAN people were more likely to go without a mammogram.

- Pap smears. The share of people in the recommended groups for screening who did not receive a recent pap smear did not significantly change for most groups between 2012 and 2020. However, it increased from 17% to 22% for White people and from 31% to 36% for Asian people. As of 2020, Black people were less likely than White people to go without a recent pap smear (17% vs. 22%), while all other groups were more likely to have not received one, with the largest difference for Asian people (36% vs. 22%). However, research has found that Black women compared to all groups are the least likely to receive human papillomavirus (HPV) co-testing with pap smears.

- Colorectal screening. The share of people in the recommended groups for screening who were not up-to-date with colorectal cancer screening decreased for most groups between 2012 and 2020. Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) people had the largest decrease, with the share falling by 18 percentage points from 46% to 28%, followed by Hispanic people who had a decrease of 10 percentage points, from 47% to 37%. As of 2020, Hispanic, Asian, and AIAN people were more likely than White people to not be up to date with colorectal cancer screening tests, while there were no significant differences between White and Black people in the recommended screening group.

- Other research suggests that African American people face disparities in receipt of prostate screening relative to their increased risk. Similarly, eligible Black adults are less likely to undergo lung cancer screening compared to all other groups and less likely to complete subsequent annual screening for lung cancer compared to White patients. Individuals in rural areas, in general, are less likely to receive cancer screening compared to their urban counterparts, though these findings are mixed for different racial and ethnic groups.

Data suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to decreases or delays in cancer screening. Overall, health care use and spending dropped precipitously in the spring of 2020 when many social distancing measures were put in place to mitigate the spread of coronavirus. While health care use and spending began to rebound as the year progressed, overall spending remained down as of December 2020 due to a decrease in utilization of non-COVID medical care. Analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that, during California’s stay-at-home order, cervical cancer screening rates among approximately 1.5 million women in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) network decreased approximately 80% compared with baseline. The decrease was similar across all racial/ethnic groups in the KPSC network and returned to near normal after reopening. According to an analysis of electronic health records by Epic Health Research Network, average weekly screenings for breast, colon, and cervical cancers dropped by 94%, 86%, and 94%, respectively, during January 20–April 21, 2020, relative to the averages before January 20, 2020. A follow-up study conducted in July 2020 showed that weekly screening rates were rising but had not yet reached pre-pandemic levels. Other research found that between January-June 2020, breast and cervical cancer screening rates fell among low-income women, with the highest decreases among AIAN, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Hispanic people. Subsequent research in Washington State found similar trends with greater reductions in breast cancer screening for communities of color compared to their White counterparts, and larger fall offs in screening for women in rural areas compared to urban areas during the pandemic. More recent research in Massachusetts found that over the remainder of 2020, while overall cancer screening appeared to have recovered (and even increased compared to pre-pandemic for all cancer screening, except for colonoscopy), the pandemic accentuated racial disparities in mammography for Black and Hispanic patients.

Research suggests that people of color receive later stage diagnoses for some types of cancer compared to their White counterparts. For many cancers, stage of diagnosis may be one of the most important predictors of survival, where people diagnosed at earlier stages have better survival outcomes. For certain cancers, disparities in stage of diagnosis despite comparable screening rates may be related to screening guidelines not accounting for earlier onset and increased age-specific cancer incidence for different groups, as well as disparities in quality of screening techniques and delays in diagnostic evaluation. Furthermore, national surveys do not distinguish between screening and follow-up mammograms, which may contribute to overestimates of screening. Recent analysis from the American Cancer Society finds that, among people diagnosed with cancers for which screening is recommended (lung, colorectum, female breast, cervix, and prostate), Black people generally had the lowest proportion of localized-stage cancer and the highest proportion of distant-stage cancer compared with other racial and ethnic groups, except for prostate cancer, for which AIAN men had the highest proportion of distant-stage disease. Black people were also more likely than other groups to be diagnosed with advanced disease for most other cancer types. Other research shows that, compared to White patients, Black patients present with more advanced disease at diagnosis across prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. Research further shows that, across multiple tumor types, Black patients present with higher-grade and more aggressive disease compared to White patients, and among those with endometrial cancer, Black patients are more likely to have subtypes associated with worse outcomes. Hispanic people are more likely than White people to be diagnosed with distant stage lung cancer, yet have lower lung cancer mortality compared to both Black and White people. Prior work has also found that compared to White patients, AIAN patients have more advanced disease at diagnosis and worse survival outcomes for multiple cancers. For skin cancers, Black patients have the highest percentage of late-stage melanoma and increased mortality compared to White patients, likely secondary to a higher proportion of later stage diagnoses, although other studies have found that increased mortality rates persist even for earlier stage diagnoses.

Racial disparities in cancer care and treatment have also been identified, particularly for diagnostic and treatment delays, which contribute to worse survival outcomes. Evidence suggests that Black patients are less likely than White patients to receive stage-appropriate treatment or guideline-concordant care across multiple types of invasive cancers. Compared to White patients, Black patients are less likely to receive a lung cancer screening after receiving a referral, are less likely to receive a provider recommendation for surgery for lung cancer, and are more likely to refuse surgery after it is recommended. Black people also are treated less frequently with chemotherapy and radiation for colorectal cancer. Furthermore, research has found lower rates of provider recommendation for colorectal screening for Black patients compared to their White counterparts. For breast and gynecological cancers, Black and Hispanic women are less likely than White women to receive certain evidence-based workup procedures or guideline recommended treatments. Other work has found that, compared to White women with similar treatment plans, Black women more often have delays in breast cancer treatment initiation. Research has similarly found that compared to White patients, Black and Hispanic patients have increased delays in receipt of surgery for breast cancer. While less studied, work has found that Asian women have a higher rate of receiving no follow-up after abnormal breast cancer screening compared to White women, with these differences being starkest among Filipina and Vietnamese women.

People of color are also more likely to report unmet needs for cancer care, including supportive care. Across communities of color, unmet socioeconomic and supportive care needs are linked to poor cancer therapy adherence. Even after adjusting for differences in socioeconomic status and health system access, research finds that U.S.-born Black people and foreign-born Latino and Asian people are more likely to perceive an unmet need in cancer care than U.S.-born White people. Furthermore, Hispanic cancer survivors report worse quality of life and unmet supportive care needs (including information about disease, psychological support, pain management, and treatment side effects) compared to White cancer survivors. Similar work has identified a high prevalence of unmet needs in physical health concerns, emotional support, and daily activity challenges for Asian and Pacific Islander cancer survivors and a shortage of patient navigators and support groups for AIAN cancer survivors.

Factors Contributing to Racial Cancer Disparities

Research suggests that racial cancer disparities are driven by a combination of inequities in health coverage and access to care, social and economic factors, and care and treatment that are rooted in racism and discrimination. Moreover, some research suggests that hereditary risk and genetic determinants for specific subtypes of cancer, in addition to environmental influences on genetic expression, may also explain a portion of disparities.

People of color are more likely than their White counterparts to be uninsured and to face other barriers to accessing health care that may limit access to cancer screening, care, and treatment. Data show that people of color are less likely to have health insurance and more likely to face barriers to accessing care, such as not having a usual source of care. Research shows that, overall, uninsured people are more likely than those with insurance to go without needed medical care due to cost and less likely to receive preventive care and services. Research further shows that financial barriers and lack of health insurance prevent adequate cancer care and management and are associated with lower screening, delays in diagnosis, decreased receipt of cancer therapies, and lower treatment adherence. One study found that Hispanic and African American women were more likely than White women to experience delays in receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer, and that insurance status was an important factor contributing to these delays. Research also finds that Black and Hispanic cancer patients are more likely than White patients to forego needed cancer treatment because of problems with transportation and that Black patients are more likely to report health care costs as a barrier to cancer care follow-up. Other work shows that lack of doctor recommendations, increased health literacy risks, and competing priorities (working multiple jobs, needing to reschedule physician appointments, and low family income) contribute to differences in receipt of breast cancer screening and pap smear testing among Black and Hispanic women. Among AIAN people, decreased availability of endoscopic services within Indian Health Service and tribal facilities, in addition to underfunded referral systems may contribute to more limited screening compared to the rest of the U.S. population.

Beyond health coverage and access to care, discrimination and bias within the health care system may contribute to cancer disparities. A significant and longstanding body of research suggests that provider and institutional bias and discrimination are drivers of racial health disparities, contributing to racial differences in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment decisions and differences in experiences obtaining health care. For example, KFF survey data show that Black and Hispanic adults are more likely to report some negative experiences with health care providers, including providers not believing they were telling the truth or refusing to provide pain medication or other treatments they thought they needed. Furthermore, recent research has found that Black patients are over twice as likely as White patients to have at least one negative descriptor in the history and physical notes of their electronic health record. Research finds that women perceiving racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination were less likely to be screened for colorectal and breast cancer compared to those not perceiving discrimination. Other studies have not found a link between race-based discrimination and receipt of cancer screening but have found that perceived discrimination due to other reasons such as age or gender is associated with decreased receipt of pap smears and mammography.

Research also points to the role of communication and interactions between providers and patients in driving disparities. This work suggests that enhancing providers’ ability to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate care, as well as increasing diversity of the health care workforce, may help address health disparities. For example, research shows that limited health literacy and limited English proficiency is associated with a decreased likelihood of breast and colorectal cancer screening among Chinese Americans. Other work finds that disparities in cancer screening among immigrants reflect a combination of cultural beliefs and attitudes, lack of knowledge, and barriers to access, which the authors conclude highlight the importance of developing culturally sensitive interventions to increase cancer screening uptake among these communities. Experiences suggest that socio-culturally and individually-tailored education and outreach, community level interventions which often rely on community health workers or religious leaders, and changes at the health systems level, such as direct referral to cancer screening from primary care providers and increased clinical equipment and staffing, may improve cancer screening and follow-up for people of color.

Disparities in exposure to risk factors, due largely to underlying social and economic inequities, drive cancer disparities. For example, historic housing policies, including redlining, and ongoing economic inequities have resulted in residential segregation that pushed many low-income people and people of color into segregated urban neighborhoods. Many of these neighborhoods have dense industrial facilities that result in high exposure to harmful air toxins. Reflecting these patterns, research finds higher exposure to air toxins that pose cancer risks in neighborhoods with concentrated shares of African American people compared to neighborhoods with higher shares of White people. Similarly, in California, higher exposure to pesticides is associated with increased rates of testicular germ cell cancer, particularly among Latino people. Beyond exposure to environmental risks, certain health behaviors may influence cancer risks and outcomes, such as smoking, obesity, alcohol consumption, and limited physical activity. These individual health behaviors are often shaped by broader social and economic factors, such as access to healthy food, financial ability to purchase food, availability of green space, and time to engage in leisure activities. Data show that AIAN and Black adults are more likely than White adults to smoke, while Asian and Hispanic adults have lower smoking rates. Moreover, Black, AIAN, NHOPI, and Hispanic adults are more likely to be obese than White adults, while Asian adults are less likely to be obese. Research further suggests that Latino and African American people are more likely than their White counterparts to have multiple behavioral risks that may contribute to cancer risk. However, research also finds that Black patients diagnosed with lung cancer are less likely to be chronic smokers compared to White patients and that, even at lower levels of smoking, Black and AIAN patients have higher rates of lung cancer compared to White patients, suggesting that smoking may not be the main driver of lung cancer disparities for these groups. Increased prevalence of comorbidities among people of color, such as diabetes, may also influence disparities in cancer survival and treatment outcomes. Moreover, foreign-born Asian and Latino people may face an increased risk for specific cancers associated with infection with cancer-associated pathogens that have higher incidence in their countries of origin.

While socioeconomic and health care access factors are primary drivers of cancer disparities, research also suggests that hereditary risk and genetic determinants for specific cancer subtypes may explain a portion of disparities. Some genetic determinants may influence susceptibility due to genetic variants or cancer-driven gene mutations in obesity, chronic inflammation, and immune responses. Research further suggests that environmental influences on gene expression may play a role in explaining racial disparities in cancer incidence and progression. For breast cancer, American Cancer Society analyses consistently find that Black people have the second highest incidence rate for female breast cancers after White people, but disproportionately higher rates of triple negative breast cancers and increased likelihood of being diagnosed with high-grade and metastatic breast cancer compared to all other groups. Hormone receptor status for breast cancers is a significant factor contributing to survival disparities, with triple negative breast cancers being less likely to be detected through screening and associated with worse prognosis, high frequency of metastasis, and lower survival compared to other breast cancer subtypes. Research has linked a higher prevalence of triple negative breast cancers among Black women to West African ancestry and specific birthplace. However, prior research has noted that tumor biological differences may contribute less to racial disparities in cancer outcomes compared to health care access barriers, and that there are no racial differences in efficacy of local or systemic therapy for breast, lung, or colorectal cancers.

Current screening guidelines for some cancers may also contribute to disparities by not accounting for differences in cancer risk across communities. Cancer screening guidelines have been developed based on clinical trials that largely underrepresented communities of color and, as such, may not reflect variations in cancer incidence and risk factors among different groups. In 2020, the American Thoracic Society released a statement noting that lung cancer screening guidelines do not recognize disparities in smoking behaviors or lung cancer risk and suggesting that researchers, providers, and professional organizations should consider an approach that includes eligibility assessments for high-risk individuals who are excluded under the guidelines. Research showed that under these USPSTF screening guidelines African American and Hispanic people were less likely than White people to be eligible for lung cancer screening despite having equal or greater risk of lung cancer compared to White smokers. Although the screening guidelines were updated in March 2021, this research further found that while the shares of people eligible for screening increased across groups, these disparities persisted. Moreover, some researchers have suggested that separate prostate cancer screening guidelines should be utilized for African American men given their higher rates of incidence and mortality, pointing to the lack of racial diversity in the studies upon which existing guidelines are based. For breast cancer, work has suggested promoting screening before the age of 50 to reduce mortality disparities, given the younger age of onset and higher incidence of certain cancer types among Black women. The USPSTF currently recommends breast cancer screening prior to the age of 50 as a Grade C guideline, which means it is suggested providers offer or provide this service for selected patients depending on individual circumstances. For colon cancer, there have similarly been efforts to lower the age to begin screening to 45 years for Black patients. As of May 2021, USPSTF guidelines were updated to begin colorectal cancer screening at age 45 as a Grade B recommendation, meaning it is suggested that providers offer the service to all eligible people. This change was made to reflect increasing colorectal cancer incidence at a younger age in the general U.S. population and higher rates among Black and AIAN people.

Underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic adults and other people of color in oncology clinical trials may contribute to cancer treatment and mortality disparities. Research has identified multiple barriers to participation in clinical trials for people of color, including lack of understanding and information about trials, fear and stigma of participating, and time and resource constraints associated with trial participation (including financial burden, time commitment, transportation, and compensation). Furthermore, research suggests that physicians are less likely to discuss clinical trials with patients of color and that trials may exclude a significant portion of Black patients due to co-existing comorbidities or lab cutoffs. Research has found that when offered to participate, at least half of patients offered participation in a clinical trial do participate, and that Black patients participate in clinical trials at similar rates compared to White patients. Moreover, previously limited coverage of clinical trial participation by Medicaid may have exacerbated underrepresentation in trials, given that people of color are disproportionately covered through Medicaid. In 2021, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued new requirements for all states to cover routine patient costs associated with clinical trial participation. However, Medicaid does not cover ancillary costs of trial participation, such as those related to childcare and employment. Medicaid does offer a separate non-emergency medical transportation benefit, while the Food and Drug Administration does not consider reimbursement for travel expenses to and from clinical trial sites or associated costs.

Looking Ahead

Overall, the data suggest that continued efforts within and beyond the health care system will be important to reduce ongoing racial disparities in cancer, many of which are rooted in systemic racism. Within the health care system, these may include ongoing efforts to reduce gaps in health insurance, increase access to care, and eliminate discrimination and bias. Beyond the health care system, addressing broader social and economic factors, including exposure to environmental risks and disparities in behavioral risks will also be important. Furthermore, there are ongoing discussions about reevaluating the implications of current cancer screening guidelines for disparities and whether to adjust guidelines or screening approaches to account for higher prevalence and risk for cancers among different communities. Moving forward, increasing diversity among oncology clinical trials and within the health care workforce will also be important for addressing disparities in cancer care and treatment, and ensuring that all people benefit from continued advancements in cancer treatment.