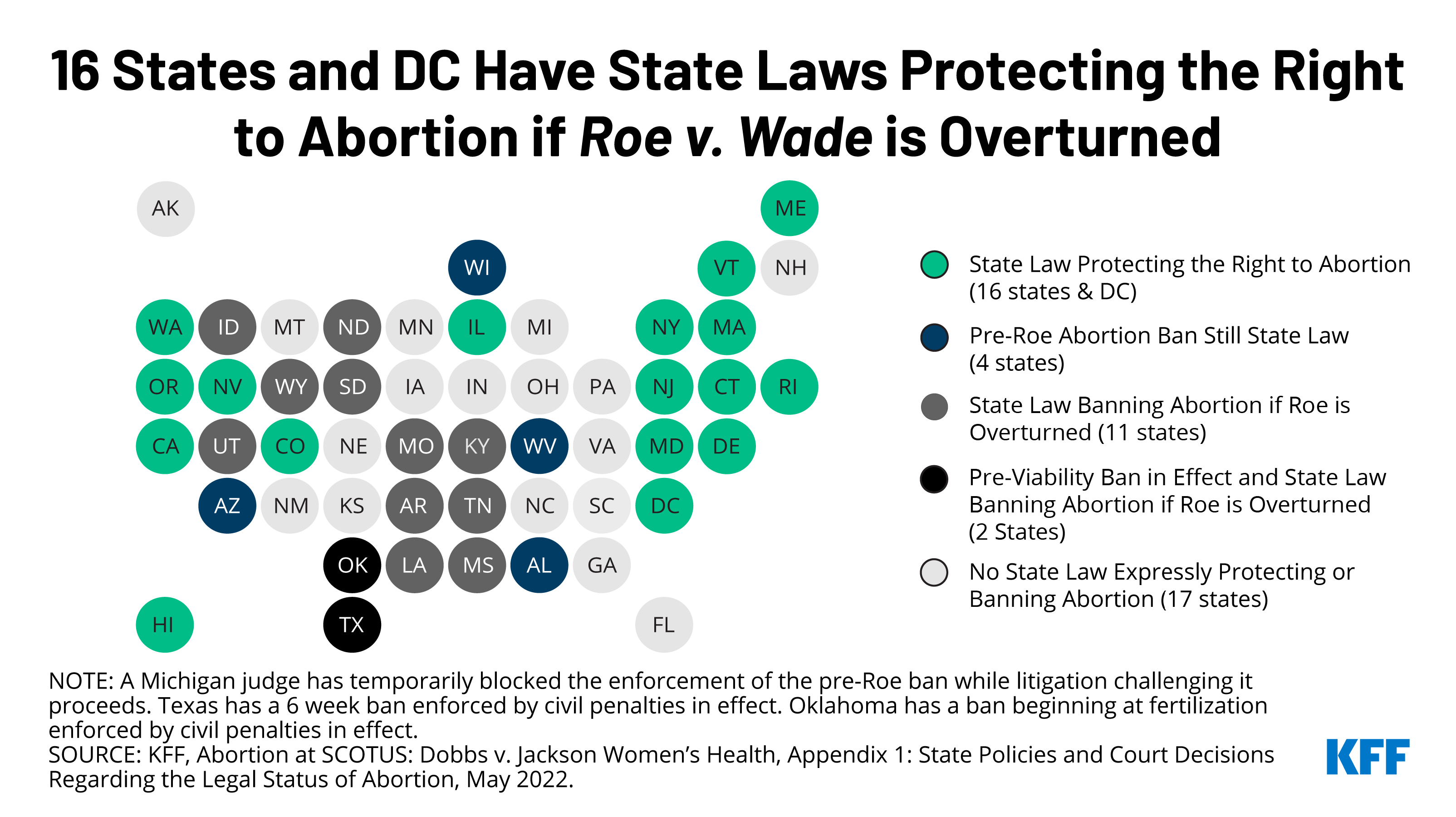

In recent months, many states have enacted laws to either prohibit abortions or to expand and protect access to abortion in anticipation of the Supreme Court’s likely ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade in the Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health case. There has been less clarity, however, about what abortion access will be like in the 17 states that do not have any explicit laws either upholding abortion rights or prohibiting abortion. If the Court rules to overturn Roe, then it is anticipated that while some states may not fully ban abortion, some will act to further restrict abortion access through new or expanded abortion restrictions to regulate abortion providers and the provision of abortion care.

Since the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, states have not been permitted to ban abortions before viability. However, the High Court’s ruling in the Planned Parenthood v Casey case allowed states to regulate the abortions that were done before fetal viability, so long as the regulation did not create an “undue burden” for people seeking abortions. If the Supreme Court overrules Roe v. Wade, states will be permitted to restrict access to abortion before the point of viability and to regulate abortions without any federal constitutional standards. It is likely that some of the states that will not prohibit abortion will have so many restrictions that access to abortion will be extremely limited, essentially blocking most abortions without enacting an outright ban.

In the 17 states without explicit laws prohibiting or protecting abortions, we present a number of indicators to assess abortion access, including abortion restrictions, the number of clinics, and women of reproductive1 age per clinic, as well as State Supreme Court rulings interpreting the right to abortion in that state.2 We included seven main categories of abortion restrictions: counseling requirements, waiting periods, ultrasound requirements, parental notification or consent requirements, gestational limits, prohibitions on insurance coverage of abortion3 , and regulations on facilities or clinicians providing abortion. Some states might have enacted other abortion restrictions or abortion-specific regulations that are not included in our review.

Five of these states (Alaska, Florida, Kansas, Minnesota, and Montana) have a prior State Supreme Court decision interpreting a right to abortion in the State constitution. There is current litigation challenging these Court decisions in Florida and Montana. In Kansas, there is a constitutional amendment on the November ballot to amend the Kansas Constitution to explicitly state that nothing in the state constitution creates a right to abortion or requires government funding for abortion and that the state legislature has the authority to pass laws regarding abortion.

In ten of these states, the legislatures have a history of enacting many laws that restrict abortion. Even if these states do not prohibit abortion outright, it is likely that many people seeking abortions in these states will not be able to access care. It is also important to consider that eleven of these states will have gubernatorial elections this year and the outcome of these elections will play a role in the future of abortion access in several of these states.

While it’s not possible to precisely predict the extent of abortion access in these states, the number of abortion restrictions, abortion coverage policy, and the partisan composition of the state legislature and governor’s office today can give us a good sense of what the future holds in many states. Future litigation resulting in state Supreme Court rulings and the outcomes of the 2022 and future elections will also be critical in determining the extent of abortion access in these states.

Alaska

The Alaska Supreme Court found that the state constitution protects the right to abortion.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 1

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions: None

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 5

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 32,300

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor and legislature, and attorney general (AG). AG is appointed by the governor. Supreme Court justices are appointed in part by the governor.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Republican incumbent running

- Potential for the House to flip

Florida

The Florida Supreme Court found that the state constitution protects the right to abortion. Florida enacted a 15-week abortion ban that is scheduled to take effect July 1, 2022; it is being challenged by two lawsuits as being in violation of the state constitution.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 7

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

- Health insurance exchange

- Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 55

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 82,892

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor, legislature, and attorney general. Supreme Court justices are appointed by the governor.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Republican incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Republican incumbent running

Georgia

Georgia has enacted a 6-week ban that has been temporarily blocked by a Court. If the U.S. Supreme Court allows states to ban abortion at any point during pregnancy, then Georgia could implement this law.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 6 (one restriction temporarily blocked)

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

- Health insurance exchange

- Public employee plans

- Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 15

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 169,260

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor, legislature, and attorney general. Supreme Court justices are elected on a non-partisan basis.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Republican incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Republican incumbent running

- Three non-partisan Supreme Court seats

Indiana

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 7

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions: All market segments including Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 7

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 216,785

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor, legislature, and attorney general (elected). Supreme Court justices are appointed in part by the governor.

Key 2022 state elections: None

Iowa

On June 17, 2022, the Iowa Supreme Court overturned the 2018 decision that found the state constitution protects the right to abortion. While the Court found there is no fundamental right to abortion found in the state constitution, the Court did not set a standard for how to evaluate abortion regulations but noted that they will turn to the U.S. Supreme Court decision on the Dobbs case for future insights in how they will interpret the state constitution regarding abortion.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 5

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 7

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 97,458

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor and legislature, and Democratic attorney general. Supreme Court justices are appointed in part by the governor.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Republican incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Democratic incumbent running

Kansas

In 2019, the Kansas Supreme Court found that the Kansas Bill of Rights includes the right to abortion.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 6

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions: All market segments including Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 4

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 160,156

Current partisan composition of state offices: Democratic governor and Republican legislature and attorney general. Supreme Court justices are appointed by the State Bar Association.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Democratic incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Republican incumbent running

- Ballot initiative (during its August 2, 2022, primaries) that would amend the state constitution to state that nothing in the state constitution creates a right to abortion or requires government funding for abortion and that the state legislature has the authority to pass laws regarding abortion.

Michigan

The Governor and Planned Parenthood filed a lawsuit to block the implementation of Michigan’s pre-Roe abortion ban. The Michigan Court of Claims issued a preliminary injunction that bars the state government from enforcing the ban as the litigation continues. The current attorney general, a Democrat, will not appeal this decision. If the incumbent Democrat loses the 2022 election, the new attorney general could choose whether to defend the pre-Roe ban.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 6

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions: All market segments including Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 28

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 78,165

Current partisan composition of state offices: Democratic governor and attorney general, and Republican legislature. Supreme Court justices are elected on a non-partisan basis.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Democratic incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Democratic incumbent running

- Potential for the Senate and House to flip

- Two non-partisan Supreme Court seats with the potential to shift the majority of the Court from liberal to conservative

- Pending ballot initiative (July 11 deadline for inclusion) that would create a state constitutional right to reproductive freedom, including abortion, and that the state could only prohibit abortion after fetal viability except to protect the life, physical, or mental health of the pregnant person, as determined by a clinician.

Minnesota

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 3

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions: None

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 9

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 138,226

Current partisan composition of state offices: Democratic governor and attorney general, and split legislature. Supreme Court justices are elected on a non-partisan basis.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Democratic incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Democratic incumbent running

- Potential for the House to flip

Montana

In 1999, the Montana Supreme Court found that the state constitution protects the right to abortion. Montana’s Attorney General is challenging the state's constitutional protection.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 3 (two are temporarily blocked)

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

- Health insurance exchange

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 7

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 31,898

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor, legislature, and attorney general (elected). Supreme Court justices are elected on a non-partisan basis.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Two non-partisan state Supreme Court seats, with the potential to shift the majority to potentially conservative

Nebraska

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 7

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions: All market segments including Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 3

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 142,036

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor and attorney general. Legislators are elected on a nonpartisan basis. Supreme Court justices are appointed in part by the governor.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Republican incumbent not running

- Attorney general, with the Republican incumbent not running

New Hampshire

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 3

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 7

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 41,300

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor, legislature, and attorney general (appointed by the governor). Supreme Court justices are appointed by the governor.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Republican incumbent running

New Mexico

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 0

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions: None

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 6

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 76,010

Current partisan composition of state offices: Democratic governor, legislature, and attorney general. Supreme Court justices are elected on a partisan basis.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Democratic incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Democrat incumbent not running

North Carolina

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 7

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

- Health insurance exchange

- Public employee plans

- Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 16

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 149,847

Current partisan composition of state offices: Democratic governor and attorney general (elected), and Republican legislature. Supreme Court justices are elected on a partisan basis.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Two partisan state Supreme Court seats with the potential to shift the majority of the Court from Democrat to Republican

Ohio

Ohio has enacted a 6-week ban that has been temporarily blocked by a Court. If the U.S. Supreme Court allows states to ban abortion at any point during pregnancy, then Ohio could implement this law.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 7

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

- Health insurance exchange

- Public employee plans

- Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 9

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 285,661

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor, attorney general, and legislature. Supreme Court justices are elected on a partisan basis.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Republican incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Republican incumbent running

- Three partisan Supreme Court seats that could shift the majority from Republican to Democrat

Pennsylvania

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 6

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

- Health insurance exchange

- Public employee plans

- Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics in 2021: 16

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 173,246

Current partisan composition of state office: Democratic governor and attorney general (elected), and Republican legislature. Supreme Court justices are elected on a partisan basis.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Democratic incumbent not running

South Carolina

South Carolina has enacted a 6-week ban that has been temporarily blocked by a Court. If the U.S. Supreme Court allows states to ban abortion at any point during pregnancy, then South Carolina could implement this law.

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 7

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

- Health insurance exchange

- Public employee plans

- Medicaid

Number of abortion clinics 2021: 3

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 380,350

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor, legislature, and attorney general. Supreme Court justices are elected by the legislature.

Key 2022 state elections:

- Governor, with the Republican incumbent running

- Attorney general, with the Republican incumbent running

Virginia

Number of abortion restriction indicators: 2

Abortion-related health insurance coverage prohibitions:

- Medicaid

- Public employee plans

Number of abortion clinics 2021: 17

Number of women of reproductive age per clinic: 114,086

Current partisan composition of state offices: Republican governor and attorney general (elected), and split legislature. Supreme Court justices are elected by the legislature.

Key 2022 state elections: None