A 50-State Review of Access to State Medicaid Program Information for People with Limited English Proficiency and/or Disabilities Ahead of the PHE Unwinding

Issue Brief

Executive Summary

State Medicaid websites are a key source of information and an avenue for enrollment in or renewal of coverage for many applicants and existing enrollees. Medicaid households include a disproportionate share of nonelderly adults with limited English proficiency (LEP), and three in ten nonelderly Medicaid adults report having a disability. Moreover, some individuals have LEP as well as a disability. When the continuous enrollment requirement related to the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) ends and states resume regularly scheduled redeterminations and renewals, individuals with LEP and/or disabilities may be at increased risk of losing coverage, despite remaining eligible, due to barriers in accessing eligibility and renewal information. Several federal laws require state Medicaid agencies to provide information in a way that is accessible to people with LEP and people with disabilities (Appendix).

This issue brief reviews accessibility of information for people with LEP and people with disabilities provided through state Medicaid websites, online application landing pages, and PDF applications and call center automated phone trees as of June 16, 2022. The analysis shows that while states have taken some steps to support access to information and applications for people with LEP and people with disabilities, gaps in accessibility remain. Given the potential challenges people with LEP and people with disabilities may face maintaining coverage once Medicaid renewal and redeterminations resume following the end of the public health emergency, specific steps to minimize barriers and ensure easy access to information, applications, and assistance could help prevent coverage losses among those who remain eligible.

Most states have taken steps to support access to information and applications for people with LEP and people with disabilities. Such steps include the following:

- Nearly every state (49) translates information on their homepage, their online application landing page, and/or their PDF Medicaid application into languages other than English. However, there is variation across and within states in terms of which resources are translated and how many translated languages are available. Just under two-thirds of states (32) translate information on their Medicaid homepage into a language other than English, 36 states translate their online application landing page into at least one other language, and 39 states make a PDF application available in at least one other language than English. The number of languages other than English ranges from 1 to over 100 in states using automated translation systems such as Google Translate, although as noted below, there may be quality issues associated with automatically translated information. The languages most commonly available include Spanish, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Tagalog. Online application landing pages and PDF applications are typically available in fewer languages than homepages, with translations of these resources often limited to only Spanish.

- A total of 46 states include multilingual tagline notices about how to obtain language assistance services on or within one click of their homepages online application landing pages and/or on their PDF applications. In these states, taglines are provided in between 1 and 55 languages other than English, with most of these states including taglines in at least 15 languages in addition to English. All states with taglines include taglines in Spanish. In addition to Spanish, the most common other languages in which taglines are offered are Chinese and Vietnamese.

- Forty-five states provide general information about the availability of reasonable modifications (also known as reasonable accommodations) for people with disabilities on or within one click of their homepage or online application landing page and/or on their PDF application. Examples of alternative formats and services to increase access for people with disabilities include teletypewriter (TTY) call center numbers to assist people who are deaf, hard-of-hearing, or have a severe speech impairment, which 41 states provide on their website, online application landing page, and/or PDF application. Fewer states specify how to access large print or Braille materials and/or applications (19 states) or how to request an American Sign Language or other appropriate interpreter (26 states).

- State Medicaid homepages and online application landing pages on average have fewer accessibility errors for people who are blind or have low vision compared to webpages in general. State homepages and online application landing pages were evaluated using WAVE, a suite of automated web accessibility measurement tools that includes 110 elements that assess potential accessibility errors for people who are blind or have low vision. WAVE detected an average of 11.4 errors per page across the 101 webpages assessed, compared to the average of 50.8 errors per page found on the top one million web homepages generally. About half of the assessed webpages showed five or fewer detectible errors, and 11 pages showed no detectible errors. These findings suggest that states have given notable attention to ensuring accessibility on these pages overall.

While states have taken steps to support access to information and applications for people with LEP and people with disabilities, continuing gaps in accessibility remain. Some of these gaps include:

- Multilingual information is often available in a limited number of other languages. In several states, Spanish is the only language other than English in which translated information is available on Medicaid homepages. Moreover, as noted above, translated online application landing pages and PDF applications are typically available in fewer languages and often limited to Spanish. For example, 26 of the 39 states with a translated PDF application only translate it into Spanish. Of the 40 states that offer language options through call center automated menus, 31 states offer options only in English and Spanish. While Spanish is the most common language spoken among nonelderly adults in Medicaid households who have LEP, Chinese and Vietnamese are each spoken by 3% of these adults, and there are a diverse set of languages spoken overall by this group.

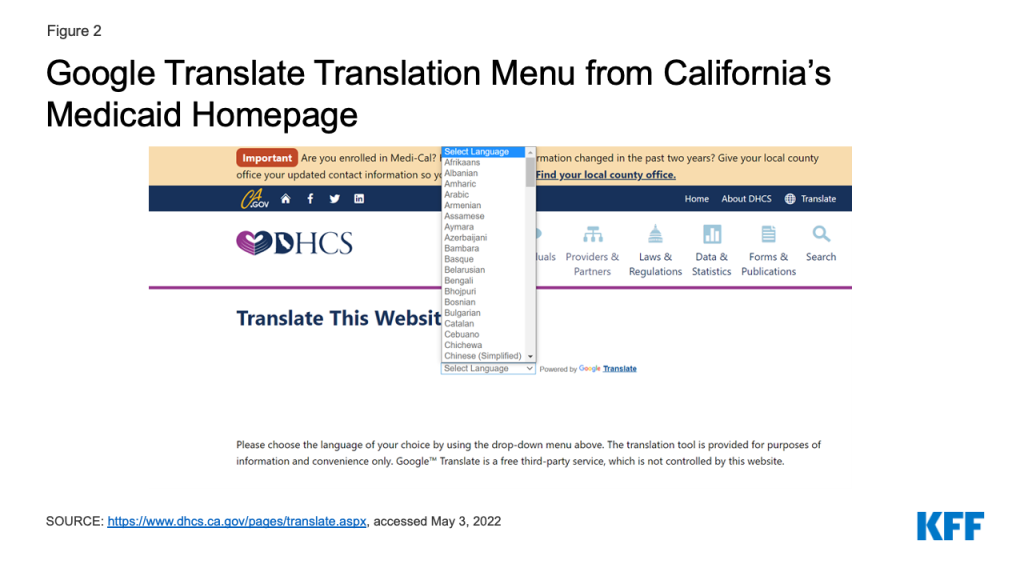

- Translated information on Medicaid homepages may be less reliable than the information available on English versions of homepages and, in some cases, translations are incomplete. Over half of states providing translated homepages use automated translations through Google Translate, which may lead to quality issues associated with the translations. Google has indicated that it is not intended to replace human translators or to be used in public health contexts without having translations verified. A few states include disclaimers that the English version of the homepage is the most reliable. Additionally, in some states, some content in the headers, footers, and/or menus of the translated versions of the homepage remains in English and/or clicking links in translated versions of the homepage leads to English content.

- Most states do not make information and applications available in multiple formats to improve accessibility for people with disabilities. A total of 19 states include information on their homepage, online application landing page, or PDF application about how to obtain materials in large print or Braille, but only two states post a large print PDF application form online. The remaining states do not mention how to access alternative formats. Making information and applications available in multiple formats is an important means of increasing access for people with disabilities. People with disabilities may access information in different ways, depending on their type of disability and type of assistive technology they use.

- Most of the webpages (in 47 states) assessed through WAVE showed at least one incidence of low contrast text, which is difficult for people with color blindness or low vision to read. Connecticut is the only state that allows users to change the homepage to a “high contrast” mode to improve readability for users. Other commonly detected accessibility issues included missing labels to describe the various fields of content in a form (24 states) and images missing alternative text (23 states).

- Nearly all state call centers (49 states) answer with an automated phone tree, which can increase accessibility challenges for people with LEP and/or intellectual, developmental, or mental health disabilities. In 12 states with automated phone trees, the first set of menu options include the option to speak to a live person. As of the time of our data collection, the call center wait time to speak with a live person was less than 15 minutes in 34 states, while in 8 states the wait time was more than 15 minutes, and in the remaining 7 states, we could not reach a live person.1 Access to a live person can improve accessibility for people with LEP and/or intellectual or developmental disabilities and people with mental health disabilities.

Introduction

State Medicaid websites are a key source of information and an avenue for enrollment in or renewal of coverage for many applicants and existing enrollees. Medicaid households include a disproportionate share of nonelderly adults with limited English proficiency (LEP), and three in ten nonelderly Medicaid adults report having a disability. While Spanish is the most common language spoken among nonelderly adults in Medicaid households who have LEP, Chinese and Vietnamese are each spoken by 3% of these adults, and there are a diverse set of languages spoken overall by this group. Medicaid enrollees have a variety of disabilities, including blindness or low vision; deafness or hard of hearing; intellectual and developmental disabilities such as autism or Down’s syndrome; traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries; and mental illness. Some people may have both LEP and a disability.

When the continuous enrollment requirement related to the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) ends, and states resume regularly scheduled redeterminations and renewals, individuals with LEP and/or disabilities may be at increased risk of losing coverage, despite remaining eligible, due to barriers in accessing eligibility and enrollment information. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance about the PHE unwinding reminds states about these obligations and prompts states to review their communications with people with LEP and people with disabilities as a strategy to mitigate inappropriate coverage loss. Several federal laws require state Medicaid agencies to provide information in a way that is accessible to people with LEP and people with disabilities. The Appendix provides background information on these laws.

This issue brief reviews accessibility of information for people with LEP and people with disabilities provided through state Medicaid websites and call center automated phone trees, as of June 16, 2022. We assessed homepages and call center automated menu options in all 50 states and DC and online application landing pages and PDF applications in the states that provide these resources2 (Appendix Table 1). See the Methods box for more detail.

Accessibility of Information for People with LEP

Translation of Website Information and Applications

Overall, 32 states translate information on their Medicaid program homepage into languages other than English, and 36 states provide translations of their online application landing page into other languages (Appendix Table 2 and Figure 1). The number of languages other than English range from 1 to over 100 in 18 states using automated translation systems such as Google Translate. Additional states also use Google Translate to offer translations in a more limited number of languages, while other states do not specify if the translation is based on automated software. All states that offer translation on their homepages or online application landing pages offer information in Spanish. The other languages most commonly available include Chinese, Vietnamese, and Tagalog. In general, states offer fewer translated languages on their online application landing pages than on the homepages. For example, 23 of the 36 states with translated online application landing pages only translate into Spanish.

Most states with online PDF applications (39 of 48 states) offer the application in languages other than English (Appendix Table 2 and Figure 1). In 26 of these states, Spanish is the only other language in which the PDF application is available. In the remaining 13 states, PDF applications are offered in additional languages, including in 10 or more languages in California, New York, North Carolina, Oregon and Washington. The most common other languages available are Vietnamese, Chinese and Korean. Most PDF applications ask about the applicant’s preferred spoken language, which may facilitate access to linguistically accessible communications in the future.

There may be potential quality issues with translations in states using automated translations, such as Google Translate. Google has indicated that it is not intended to replace human translators or to be used in public health contexts without having translations verified and other research has found Google Translate to be unreliable in medical contexts.3 ,4 A few states include disclaimers that the English version of the homepage is the most reliable. In some states, some content in the headers, footers, and/or menus of the translated versions of the homepage remains in English and/or clicking links in translated versions of the leads to English content.

Access to Language Assistance and Interpretation Services

Thirty-five states include multilingual taglines on or within one click of their homepages or online application landing pages with information on how to access language assistance services (Appendix Table 2). Most of these states provide taglines in at least 15 languages other than English. All 35 states include taglines in Spanish, and the other most common languages are Chinese and Vietnamese.

Most states with PDF applications (35 of 48 states) include multilingual tagline notices regarding the availability of language assistance services on the PDF application (Appendix Table 2). These taglines are generally present on the first or second page of the application or as a footer running across every page. In 26 of these states, taglines are only provided in Spanish and English, while in others, they are provided in between 2 and 15 other languages. In addition to Spanish, the most common other languages in which taglines are offered are Chinese and Vietnamese.

In 49 states, call centers answered with automated phone trees, and 40 of these states offered menu options in languages other than English. However, in 31 of these states the only other language offered through the menu is Spanish (Appendix Table 2 and Figure 1).5 In the remaining states, phone tree menus offer between two and six languages other than English. In some states, other language options are only offered after the applicant listens to a long set of options in English.

Accessibility of Information for People with Disabilities

Availability of Reasonable Modifications

Most states (43) provide general information about the availability of reasonable modifications (also known as reasonable accommodations) for people with disabilities on or within one click of their homepage or online application landing page, while 32 states provide this information on their online PDF application (Appendix Table 4 and Figure 4).6 States often provide information about reasonable modifications for people with disabilities on a separate webpage titled “Nondiscrimination policy” or “Accessibility” rather than directly on their homepage. Users can usually find these separate webpages by clicking on a “Nondiscrimination policy” link at the bottom of the homepage. States often use these separate webpages to outline their general commitment “to serving the needs of people with disabilities” (CT). Most of these separate webpages include information about free “auxiliary aids and services necessary to afford an individual with a disability an equal opportunity to participate in all services, programs and activities” (KY). Additionally, states often include information about reasonable accommodations such as alternative formats including Braille or large print materials, teletypewriter (TTY) numbers, and how to request qualified American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters on these separate webpages. The comprehensiveness of the reasonable modification statement varies across states—some states only include a general statement while other states describe the types of aids and alternative formats that are available and provide instructions on how to access them. The availability of information in plain language also is an important means of providing access for people with cognitive disabilities, though our website review did not assess content for plain language.

Alternative Written Formats for People with Disabilities

A total of 19 states provide information about how to obtain materials in large print or Braille (Appendix Table 4 and Figure 4). Most of these states list a phone number (and/or a TTY number) for individuals to call to request materials in alternative formats, such as large print, or advise users to contact their local office. Two states (CA, CO) post a large print PDF application form online,, and several states, including DE, KS, MS, NH, NY, TN, and VA, allow users to increase or decrease the font size of text on the webpage. Connecticut allows users to change the homepage to a “high contrast” mode to improve readability for users. Making information and applications available in multiple formats is an important means of increasing access for people with disabilities. People with disabilities may access information in different ways, depending on their type of disability and type of assistive technology they use.

Website Accessibility for People Who are Blind or Have Low Vision

State homepages and online application landing pages were evaluated using WAVE, a suite of automated web accessibility measurement tools that includes 110 elements that assess potential accessibility errors for people who are blind or have low vision. WAVE is developed and made available as a free community service by WebAIM (Web Accessibility in Mind) at Utah State University. WAVE assesses web accessibility, including compatibility with screen reader software, which can be used by people who are blind to convert web content to synthesized speech, and screen magnifiers or zoom, which can be used by people with low vision. Because WAVE is automated, it does not assess all aspects of accessibility that may be encountered by website users. However, WAVE does identify the accessibility errors that are most frequently encountered and that tend to have the greatest impact on users who are blind or have low vision.7 Additionally, errors identified by WAVE have been found to correlate with the existence of other accessibility issues that WAVE does not detect but which can be encountered by a website user.8 The WAVE analysis was applied to a total of 101 webpages, including the homepages for all 50 states and DC and the online application landing pages for 49 states and DC.9

The most common accessibility issue detected by WAVE is very low contrast text, with 67% of the assessed webpages (in 47 states) showing at least one incidence of this error (Appendix Table 3 and Figure 5). Overall, WAVE detected an average of seven instances of very low contrast text errors per page across the 101 webpages assessed. Low contrast text refers to the difference in brightness between text or a graphic and its background colors and is difficult for people with color blindness or low vision to read. Other commonly detected accessibility issues include missing labels to describe the various fields of content in a form (27% of pages, 24 states) and images missing alternative text (25% of pages, 23 states) (Appendix Table 3). Alternative text is used to describe the content of an image. Images that lack alternative text and forms without text labels cannot be properly identified by screen readers, making this content very difficult to access for people who rely on that technology.

The average number of accessibility errors detected by WAVE across the 101 assessed state homepages and online application landing pages is substantially lower than the average number of errors found on webpages in general. Specifically, WAVE detected an average of 11.4 errors per page across the 101 webpages assessed, compared to the average of 50.8 errors per page found on the top one million web homepages generally. The number of web accessibility errors detected on the assessed webpages varies widely across states (Appendix Table 3). Over half of the states have 15 or fewer errors across their homepages and online application pages and in seven states, there are less than five errors (Figure 5). These findings suggest that states have given notable attention to ensuring accessibility on these pages overall, although some pages may have errors that could pose difficulty for users with disabilities.

Effective Communication for People with Disabilities

Forty-one states list a TTY call center number on their homepage or online application landing page, within one click from these pages, or on their PDF application (Appendix Table 4 and Figure 6).10 These numbers are often found in different places on states websites. Some states require users to click on a “contact us” tab to find a TTY number, while others require users to click on a different link to a “nondiscrimination” or “access for users with special needs” webpage to find a TTY number. In some states, the TTY number is only available on the language assistance page. TTY numbers allow individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing to communicate by sending typed messages over the phone line. If states communicate with applicants or the public by phone, they also must handle calls via TTY or similar technology.11 While a number of states include the TTY number in their tagline notices for language assistance, a smaller number of states, such as North Carolina, provide a Spanish language TTY (Relay Service).

Twenty-six states provide information about how to request an ASL interpreter on their website and/or PDF application (Appendix Table 4 and Figure 6). One of these states (WA) directly lists this information on their homepage, while the other states require users to click on another link such as a “nondiscrimination” webpage to find information about how to request an ASL interpreter. Both TTY numbers and ASL interpreters can help promote effective communication for people who are deaf or hard of hearing that could be essential for someone to understand how to enroll in or retain Medicaid coverage.

The large majority (49 of 51) of call centers answer with an automated phone tree and only 12 of the automated phone trees include an option to speak to a live person in the first set of menu options (Appendix Table 4 and Figure 6). Two call centers (DC, SD) answer with a live person instead of an automated phone tree. Access to a live person can improve accessibility for people with LEP and/or intellectual or developmental disabilities and people with mental health disabilities. As of the time of our data collection, the call center wait time to speak with a live person was less than 15 minutes in 34 states, while in six states, the wait time was more than 15 minutes. In the remaining seven states, we were unable to reach a live person.12 The end of the COVID-19 PHE may increase these wait times, as states resume processing redeterminations and renewals.

Looking Ahead

As the COVID-19 PHE ends and states resume regularly scheduled Medicaid redeterminations and renewals, people with LEP and/or disabilities may face increased challenges to maintaining coverage despite remaining eligible due to barriers in accessing eligibility and enrollment information. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, and the Rehabilitation Act, state Medicaid agency program information must be accessible to people with LEP and people with disabilities. The Biden Administration has issued a proposed rule revising implementing regulation for Section 1557, taking steps to reverse Trump Administration policy and regulations that significantly narrowed the implementation and administrative enforcement of the regulations. The proposed rule reinstates the requirement that Medicaid agencies provide notice of the availability of language assistance services and auxiliary aids and services in both physical locations and on their websites. Additionally, the rule, for the first time, requires state Medicaid agencies to give staff clear guidance and training on the provision of language assistance services and effective communication and reasonable modifications to policies and procedures for people with disabilities in order to improve compliance. Regardless of the status of the regulations, the underlying statutory protections of Section 1557, which require meaningful access to federal programs for people with LEP and/or disabilities, remain as well as protections under other federal laws and federal Medicaid regulations that require public programs be accessible to people with LEP and/or disabilities.

As states prepare to resume Medicaid redeterminations and renewals, they can take steps to prevent and minimize potential administrative barriers to maintaining coverage, particularly for people who have LEP and/or disabilities. CMS guidance outlines specific steps states can take, including ensuring accessibility of forms and notices for people with LEP and people with disabilities and reviewing communications strategies to ensure accessibility of information. Increasing access to a live person through call centers and/or providing a dedicated call center line for people with LEP may also help improve accessibility for people with LEP and people with disabilities. Ensuring accessibility of information, forms, and assistance will be key for preventing coverage losses and gaps among these individuals.

Methods

State Medicaid websites were identified by using the first result from a Google search for the state name and Medicaid (e.g., Alabama Medicaid), with the exception of DC, Illinois, and Nevada, for which the first results were not specific to Medicaid or did not include applicant or member-facing information. For DC and these states, the second result, which was more relevant, was used. Online Medicaid application landing pages and PDF applications were identified through State Medicaid websites. In some cases, online application landing pages are housed in separate websites from the Medicaid website, for example, if the online application allows individuals to apply for multiple benefits (such as health care, food, and cash assistance) or if the application is integrated with Marketplace coverage. The analysis included examination of information available on and within one click of the Medicaid homepage and online application page as well as PDF applications, where available. An abbreviated list of indicators used to determine the accessibility and accommodation information is reproduced in Appendix Tables 1 through 4.Call center data was obtained by searching the Medicaid state homepage for the customer support call center number. Calls were made to these numbers (listed in Appendix table 1) from June 2 through June 16, 2022, between 9 AM and 5 PM EST.

KFF appreciates the assistance of Jared Smith, program manager at Utah State University Institute for Disability Research, Policy and Practice, with analyzing and interpreting the WAVE results.

Appendix

Appendix

Summary of Relevant Federal Nondiscrimination Laws

State Medicaid agency program information must be accessible to people with LEP and people with disabilities. States must provide information about Medicaid eligibility requirements, covered services, and applicant/enrollee rights and responsibilities via a website as well as orally and in writing.13 States also must allow individuals the opportunity to apply for Medicaid without delay.14 Individuals must be able to apply online, by telephone, by mail, in person, and through other commonly available electronic means.15 State Medicaid agencies must provide assistance to individuals seeking help with the application or renewal process in person, over the telephone, and online.16

Federal law requires state Medicaid agencies to provide meaningful access for people with LEP. As recipients of federal funds, state Medicaid agencies are prohibited from discriminating on the basis of national origin, pursuant to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Current regulations require state Medicaid agencies to “ensure meaningful access to… programs or activities by limited English proficient individuals.”17 People who are LEP may include those who do not speak English as their primary language and who have a limited ability to read, write, speak, or understand English. The current Section 1557 regulations, issued by the Trump Administration, reduced the regulatory standards originally adopted by the Obama Administration. The Biden Administration has issued a proposed rule taking steps to reverse Trump Administration policy and strengthen and reinstate Section 1557 regulatory standards.

The two main types of language assistance services are oral interpreting and written translation. In addition to the requirements of Title VI and Section 1557, federal Medicaid regulations specifically require state Medicaid agencies to provide information about eligibility requirements, covered services, and applicant/enrollee rights and responsibilities as well as application assistance in a timely manner and in a way that is accessible to people with LEP, though the provision of language assistance services at no cost to the individual.18 Individuals must be informed about the availability of these language assistance services and how to access them.19 At minimum, state Medicaid agencies must provide taglines in non-English languages that indicate the availability of language assistance services.20

Federal law requires state Medicaid agencies to make programs and services accessible to people with disabilities. Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) applies to state and local governmental entities, while Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and Section 1557 of the ACA apply to recipients of federal funds. All of these laws prohibit state Medicaid agencies from discriminating against people with disabilities. This means that people with disabilities cannot be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of the services, programs, or activities offered by a state Medicaid agency.21 People with disabilities also must have an equal opportunity and ability to participate in or benefit from the services, programs, and activities of state Medicaid agencies.22 Additionally, state Medicaid agencies must afford people with disabilities the opportunity to request, and must make, reasonable modifications in policies, practices, or procedures when necessary to avoid disability-based discrimination, unless doing so would result in a fundamental program alteration or result in an undue burden.23 The definition of disability is to be construed broadly in favor of expansive coverage to the maximum extent permitted.24

State Medicaid agencies must take appropriate steps to ensure that communication with applicants, participants, and members of the public with disabilities is as effective as communication with those without disabilities.25 State Medicaid agencies also must timely furnish appropriate auxiliary aids & services where necessary to afford people with disabilities an equal opportunity to participate in and enjoy the benefits of a program or activity.26 The type of auxiliary aid or service to be provided varies based on the individual’s communication method; the nature, length and complexity of the communication; and the context. Governmental entities like state Medicaid agencies must give primary consideration to the individual’s requested type of auxiliary aid or service. Auxiliary aids and services may include qualified onsite or video remote interpreters. A teletypewriter (TTY) or equally effective telecommunication system must be used when an agency communicates with applicants or enrollees by phone, and agencies must respond to relay calls in the same manner as other phone calls.27 Any automated attendant system (voicemail or interactive voice response system) to receive or direct incoming calls must provide effective real time communication.28

In addition to the requirements of the ADA, Section 504, and Section 1557, federal Medicaid regulations specifically require state Medicaid agencies to provide information about eligibility requirements, covered services, and applicant/enrollee rights and responsibilities as well as application assistance in plain language, in a timely manner, and in a way that is accessible to people with disabilities, though the provision of auxiliary aids and services at no cost to the individual.29 Individuals must be informed about the availability of accessible information and how to obtain it.30

Endnotes

- Two states (AZ, FL) require callers to enter identifying information in order to access live assistance and were excluded from this assessment. ↩︎

- If the PDF application could not be found on the homepage or online application landing page, this indicator was coded as “no” even if a PDF application was available elsewhere online. PDF applications vary widely in length, ranging from 9 to 62 pages. ↩︎

- Salame, R. (2021, April 30). Limited English Skills Can Mean Limited Access to the COVID-19 Vaccine. Slate. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2021/04/covid-19-vaccine-for-non-english-speakers.html. ↩︎

- Taira, et al. (2021). A Pragmatic Assessment of Google Translate for Emergency Department Instructions. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(11), 3361-3365. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06666-z. ↩︎

- We did not assess the availability of live multilingual call center assistance. ↩︎

- We were unable to assess this indicator for online application forms because most states require users to create an account before accessing the contents of the online application. ↩︎

- Conversation with Jared Smith, Program Manager, Institute for Disability Research, Policy and Practice, Utah State University (June 7, 2022). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- AK lacks an online application page. ↩︎

- State websites often include a brief description of TTY services explaining how the service is “designed for people who are Deaf or Hard or Hearing” (NC). For example, North Carolina’s website describes how the “relay operator reads aloud the message [the caller] typed to the other party and types the other party’s voiced message and background sounds, if any, to [the caller].” To see more about how TTY numbers can be used, see North Carolina’s infographic. ↩︎

- If the TTY number could not be found on the homepage or within one click from the homepage, this indicator was coded as “no” even if the number was available elsewhere on the website. ↩︎

- Two states (AZ, FL) require callers to enter identifying information in order to access live assistance. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. u00a7 435.905 (a). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. u00a7 435.906. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. u00a7 435.907 (a). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. u00a7 435.908 (a). ↩︎

- Nondiscrimination in Health and Health Education Programs or Activities, Delegation of Authority, 85u00a0Fed. Reg. 37,160u00a0(June 19, 2020) (to be codified at 42 CFR Parts 438, 440, and 460). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. u00a7 u00a7 435.905 (b)(1); 435.908 (a). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. u00a7 435.905 (3). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. u00a7 12131; 28 C.F.R. u00a7 35.130 (accord Rehab. Act u00a7u00a0 504 and ACA u00a7 1557). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- 28 C.F.R. u00a7 u00a7 35.130; 35.164. ↩︎

- 28 C.F.R. u00a7 35.101. ↩︎

- 28 C.F.R. u00a7 35.160. ↩︎

- 28 CFR u00a7 u00a7 35.104; 35.160. ↩︎

- 28 C.F.R. u00a7 35.161. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. u00a7 u00a7 435.905 (b)(2); 435.908 (a). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. u00a7 435.905 (3). ↩︎