Introduction

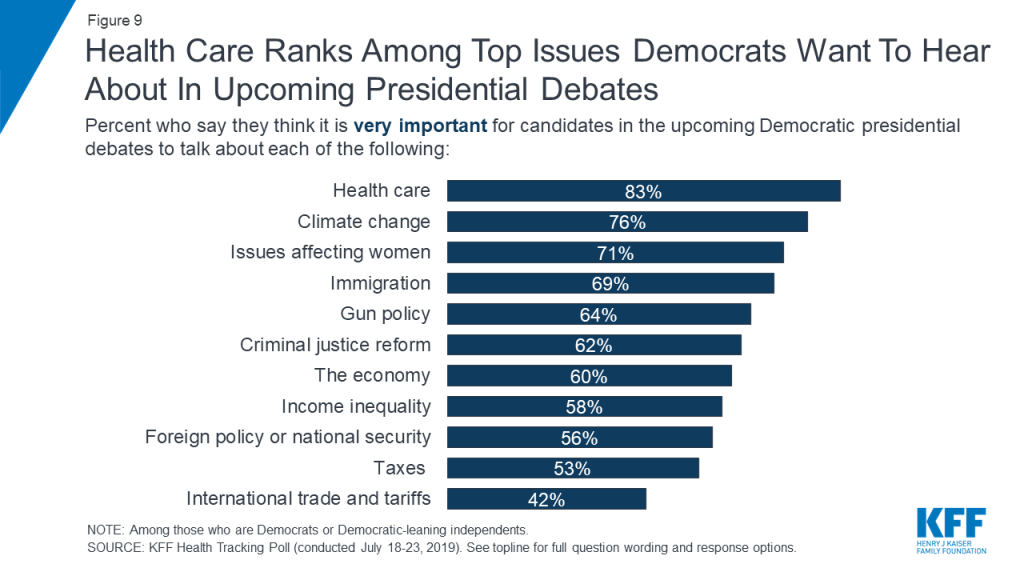

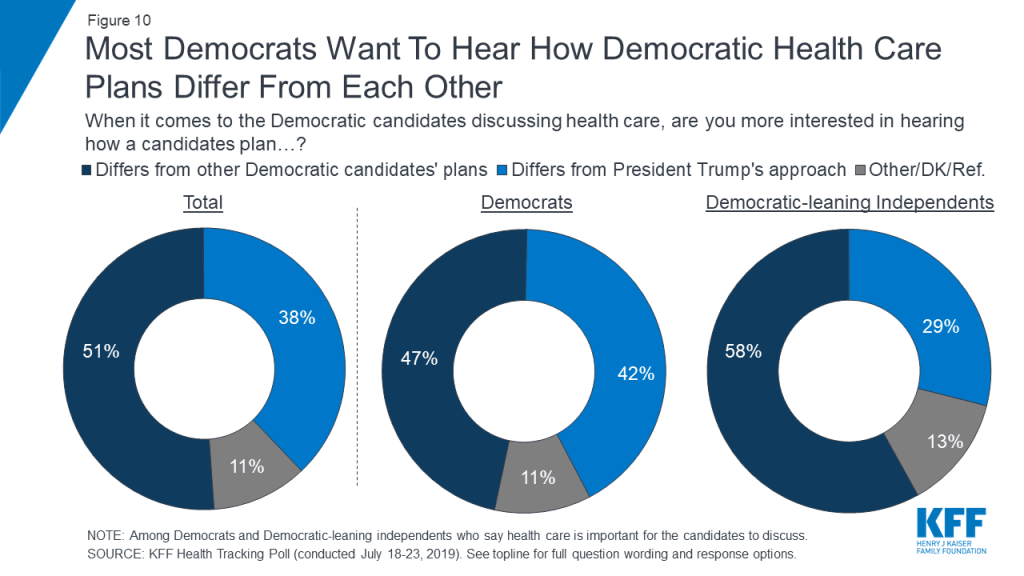

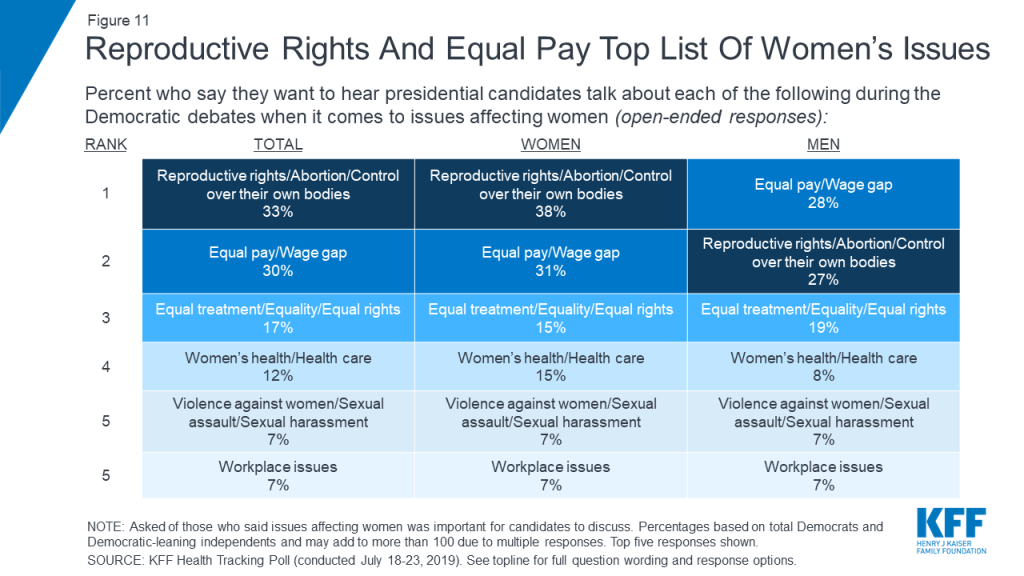

The role of private health insurance under Medicare-for-all and other proposals has emerged as a prominent issue in the Democratic primary and an important issue for voters. Candidates are debating what role private insurance should have in the U.S. health care system and the implications of such a change for individuals across the country.

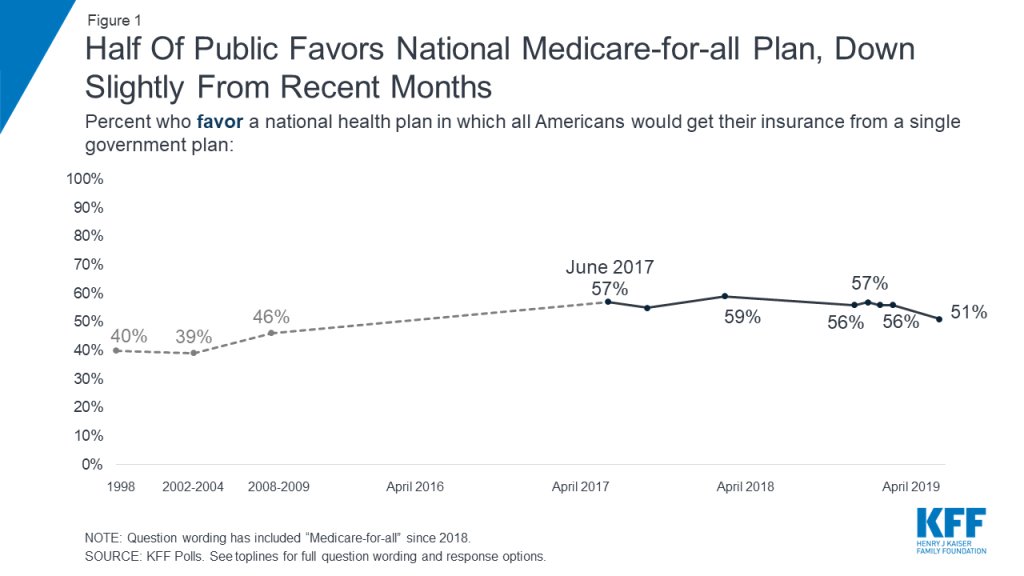

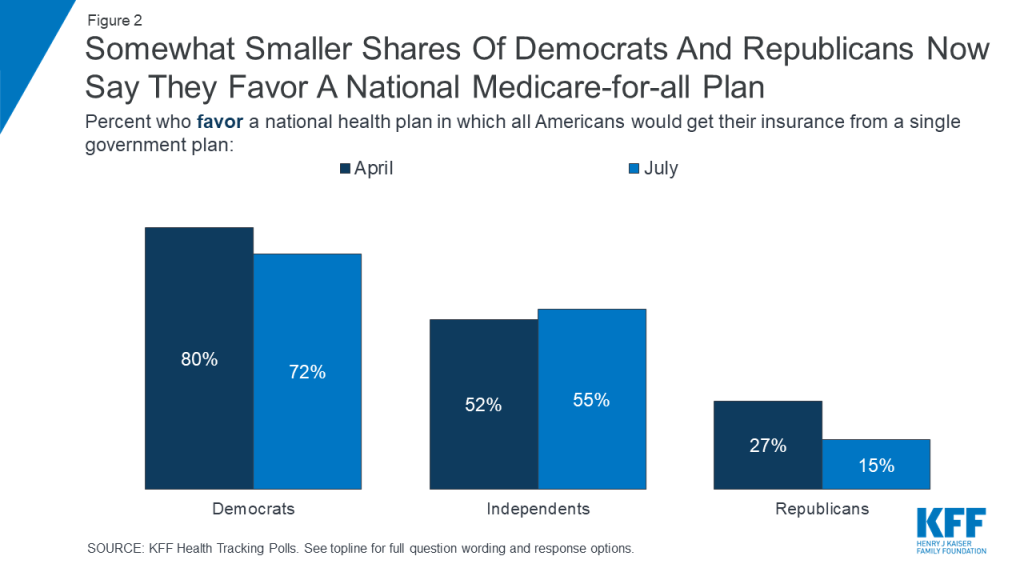

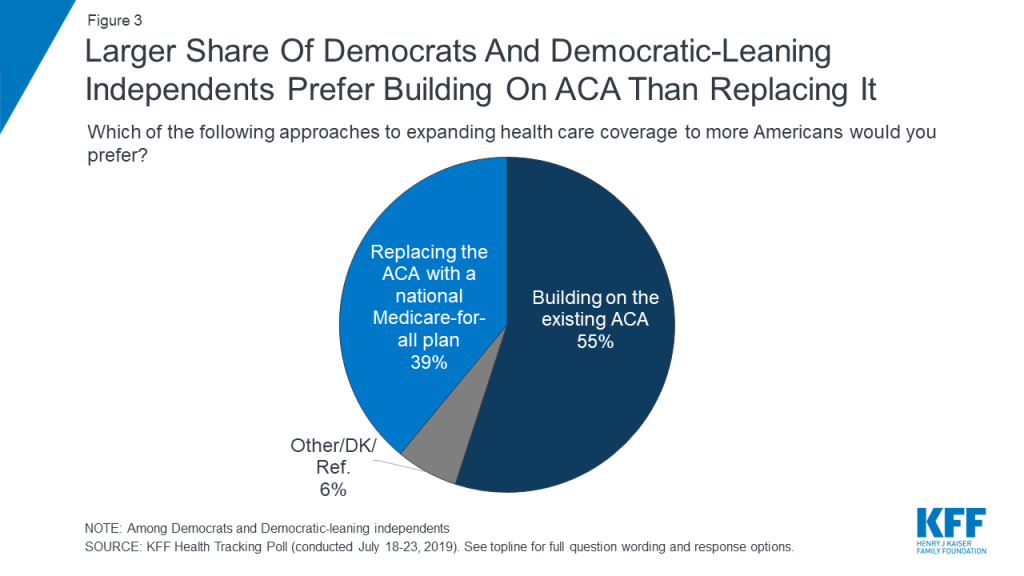

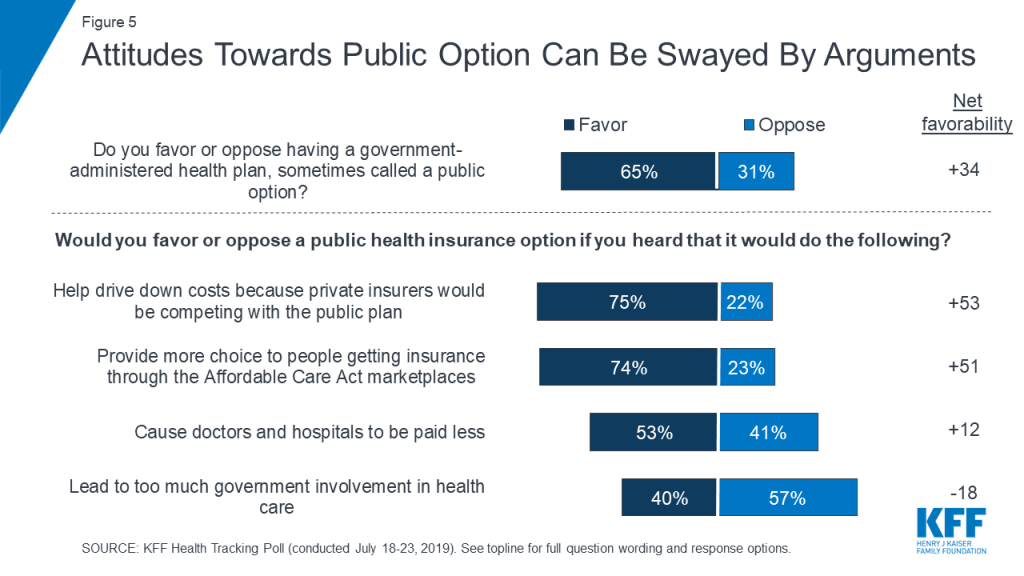

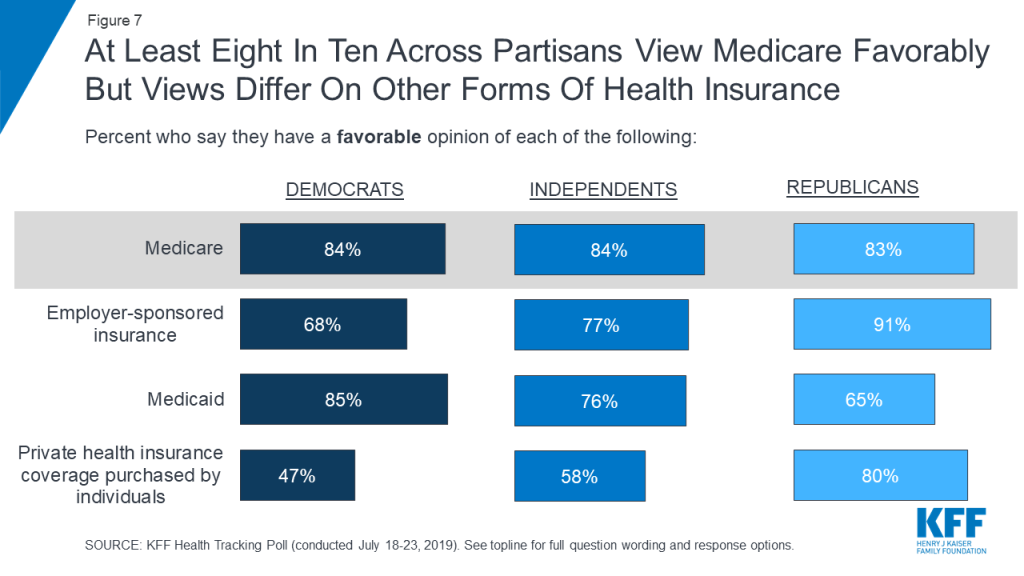

For more than two years KFF polling has found a majority of the public favoring a national Medicare-for-all plan with the most recent poll finding a slight dip in support with about half the public (51%) now saying they favor Medicare-for-all. However, surveys also show most people do not have a clear understanding about the current Medicare-for-all proposals, and how they might change the nature of coverage people have today. For example, based on a poll fielded in early 2019, 55% of the public think that they and their families would be able to keep their current health insurance under Medicare-for-all; 54% think they would continue to pay health insurance premiums and 69% think they would continue to pay deductibles and copays for covered health services. Public opinion is malleable in response to additional information and arguments about Medicare-for-all. Support for Medicare-for-all increases to 67% when people hear it would eliminate insurance premiums and reduce out-of-pocket health costs, and increases to 71% when people hear it would guarantee health insurance as a right for all Americans, but drops to 37% when people hear Medicare-for-all would eliminate private health insurance.

What’s the role of private insurance today and how would it change under Medicare-for-all and other public option proposals? This new @KaiserFamFound brief explores the issues

This brief begins by examining the role that private insurers play in providing health coverage for Americans today, not only in employer plans and the individual insurance market, but also in Medicare and Medicaid. It then discusses how that would likely change under Medicare-for-all and other proposals and summarizes evidence on consumers’ experiences with private insurance.

Current Role of Private Health Insurance in the U.S.

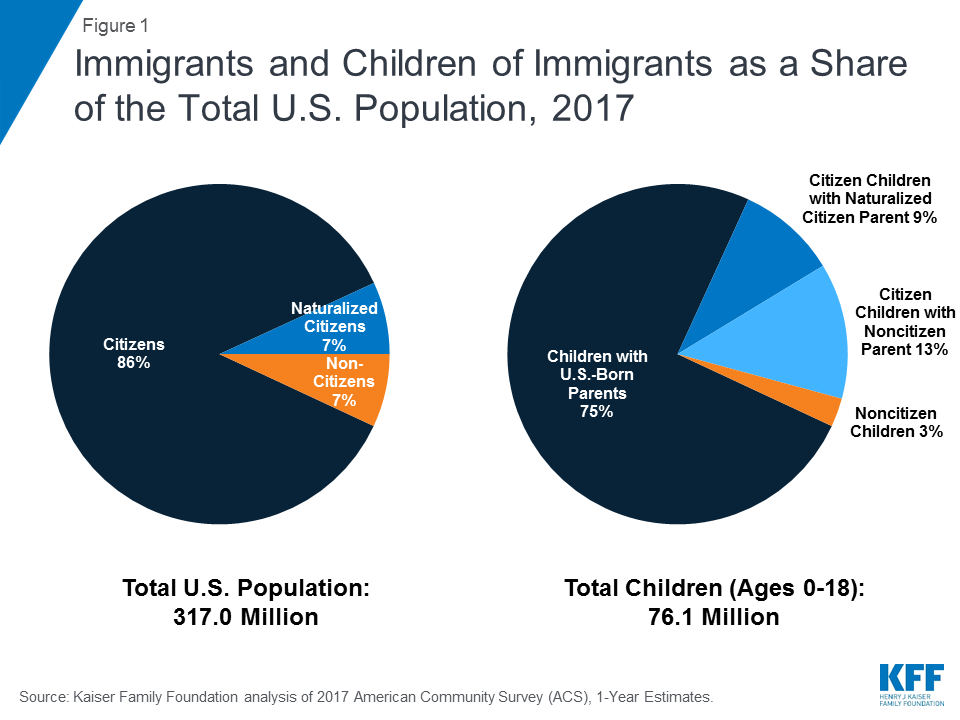

Today, the majority of the U.S. population have some form of coverage delivered by a private health insurer. This includes: non-elderly people with employer-sponsored coverage or individually purchased health insurance plans; low-income Medicaid enrollees covered by managed care organizations; people age 65 and older and younger adults with disabilities in Medicare Advantage plans; and people in traditional Medicare who also have private insurance, such as Medicare part D stand-alone prescription drug plans, supplemental (Medigap) policies, or employer-sponsored retiree health coverage.

The following coverage estimates are the most current data available for each category of private insurance. These data points cannot be summed because they derive from different sources, from different years, and because some people have private insurance from multiple sources.

Employment-based coverage accounts for the largest share of people in the U.S. with private insurance. In 2017, 153 million non-elderly people had private, employer-sponsored health coverage. Typically, employers pay most of the premium on behalf of employees and their dependents – on average 82% of the premium for single coverage and 71% for family coverage. Employees and their families are typically responsible for deductibles and other cost-sharing requirements. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires large employers to provide full-time workers and their dependents health coverage that meets minimum standards for affordability and coverage value or pay a penalty. Although not mandated by law, a majority of small firms offer health benefits.

Non-group, individually purchased coverage is another source of private health insurance. An estimated 14 million people had private insurance coverage in the non-group market (also known as the individual market) in the first quarter of 2018. Of this total, roughly three-quarters purchased coverage through the ACA Marketplaces, where subsidies are available to eligible individuals with incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Most non-group plans are ACA compliant, meaning they must cover essential health benefits and cannot discriminate based on a person’s pre-existing condition; however, recent regulatory changes have made health plans that do not comply with the ACA consumer protections increasingly available in the individual market outside the Marketplaces.

The majority of Medicaid enrollees have coverage provided by managed care plans under contract with each state’s Medicaid program. Two thirds of all Medicaid enrollees (54 million) were enrolled in Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) as of July 2017 in the 38 states and DC that contract with Medicaid managed care organizations to deliver services to at least some beneficiary populations (e.g. children, parents, ACA expansion adults). MCOs generally provide all covered services to enrollees, but states may carve out specific services from MCO contracts (e.g. long-term care, dental, or behavioral health) and deliver these through fee-for service systems or limited benefit health plans. Medicaid MCOs are subject to broad federal and state standards and beneficiary protections. Federal standards prohibit premiums for most Medicaid enrollees, unless permitted under a demonstration waiver. Federal rules also prohibit deductibles and allow nominal cost-sharing for non-exempt enrollees. Payments to Medicaid MCOs totaled nearly $264 billion in FY 2017, accounting for about 46% of total Medicaid spending. While states contract with private plans, not all enrollment and spending is for private managed care plans. For example, California has a number of public county-operated health plans.

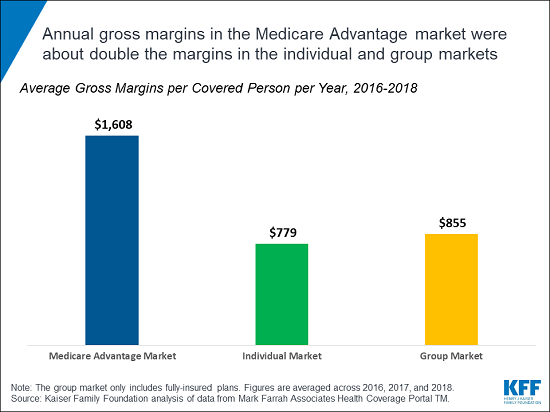

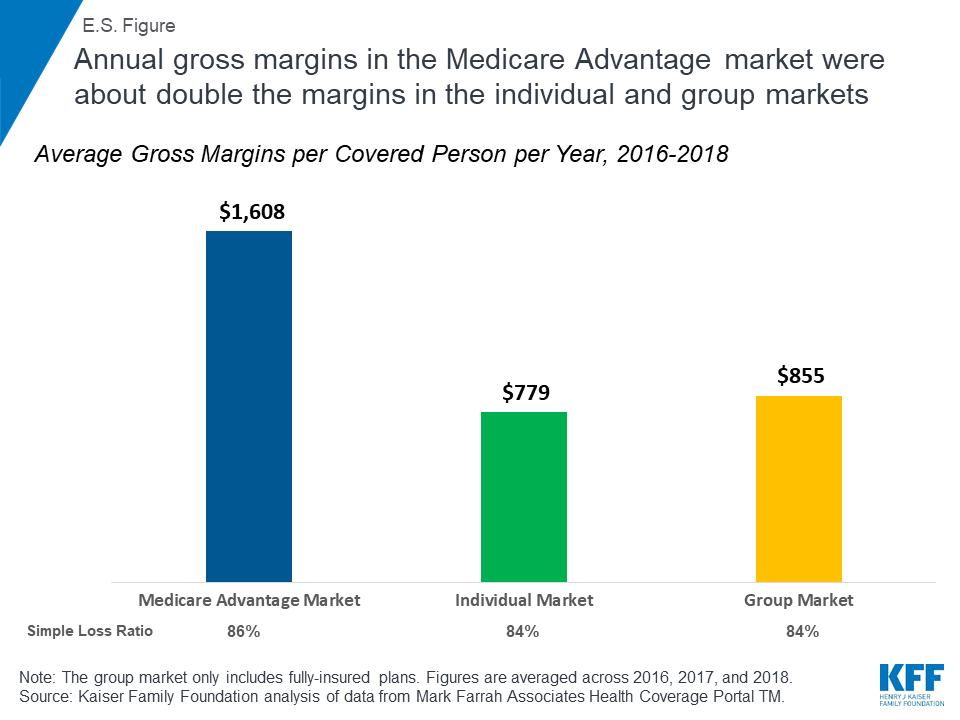

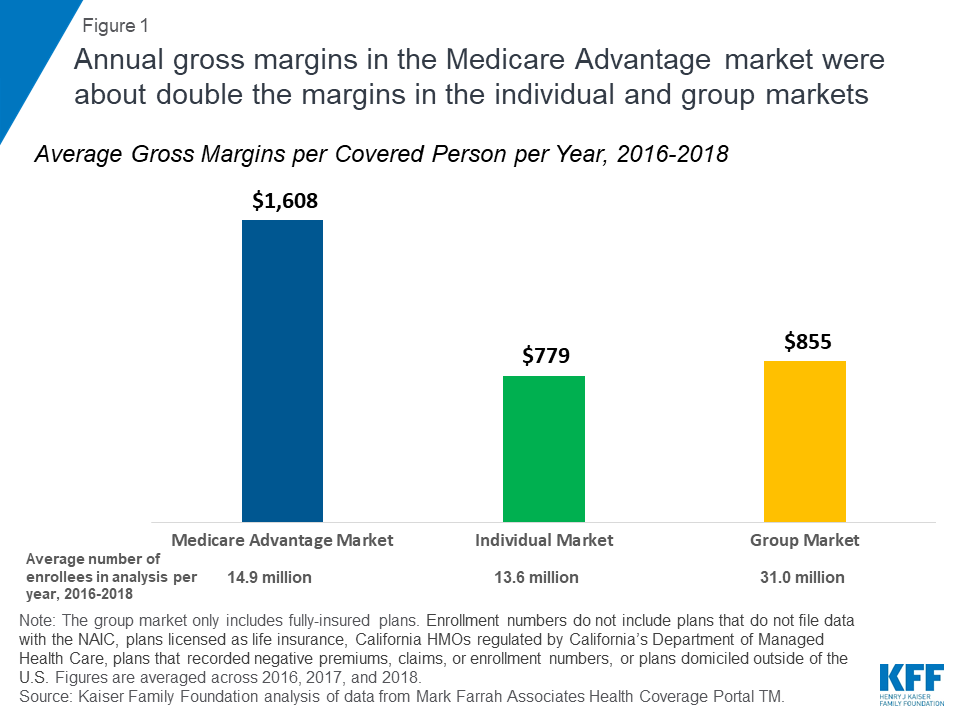

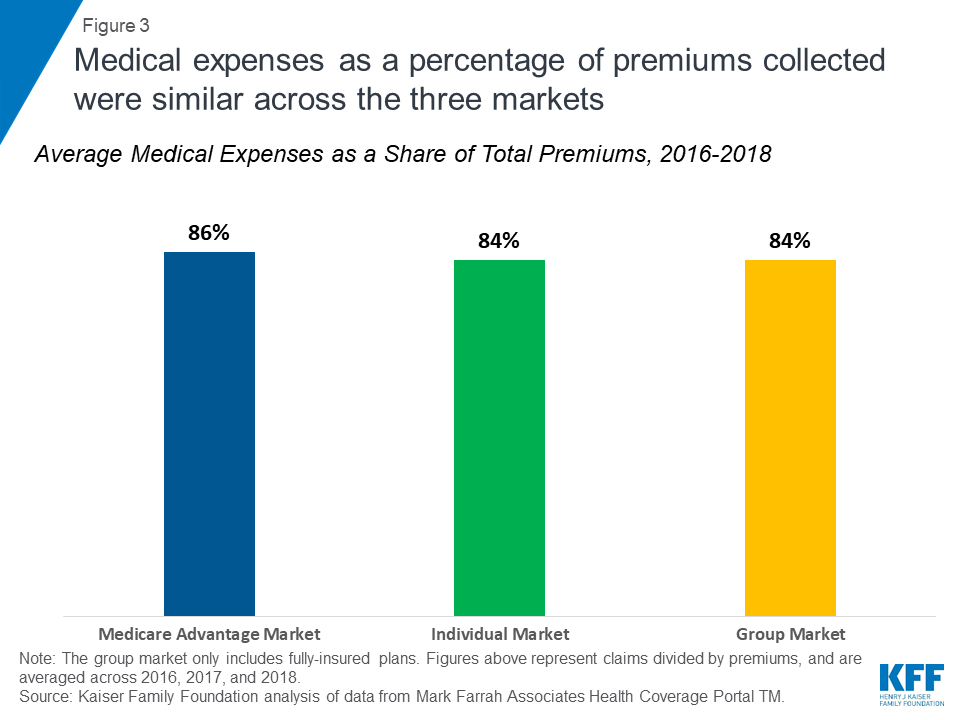

A growing share of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, such as HMOs and PPOs, which are sponsored by private insurers and paid by the federal government to provide Medicare-covered services. Among the more than 60 million people now covered by Medicare, about one-third (22 million in 2019) are in a Medicare Advantage plan. Medicare Advantage plans are required to provide all Medicare-covered services, and are subject to federal standards with respect to benefits and cost-sharing requirements, and network adequacy. Many also provide additional benefits, such as dental, vision and gym memberships. Medicare Advantage plans receive capitated, risk adjusted payments from the federal government to provide Medicare-covered services, exceeding $250 billion in 2019, sometimes supplemented by beneficiary premiums. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects nearly half of all Medicare beneficiaries (47 percent) will be in a Medicare Advantage plan by 2029.

The majority of people in traditional Medicare have additional coverage provided by one or more private plan sponsors. For example, 25 million Medicare beneficiaries in traditional Medicare are enrolled in private stand-alone Part D prescription drug plans. Enrollees typically pay an additional premium for this coverage, unless they qualify for low-income subsidies, and have cost-sharing requirements that vary across plans. In addition, nearly 20 million beneficiaries in traditional Medicare had private supplemental coverage in 2016, including 9.5 million traditional Medicare beneficiaries who purchased Medicare supplemental insurance (Medigap) policies in 2016, and another 9.6 million Medicare beneficiaries with private, employer or union-sponsored retiree health benefits that year.

Treatment of Private Insurance under Medicare-for-all and Other Public Plan Option Proposals

The role of private health insurance in the U.S. would vary across the range of proposals under discussion that establish a public program to broaden coverage and make health care more affordable. Medicare-for-all proposals would have the most far-reaching effect; under some current Medicare-for-all proposals, the new public program would replace virtually all sources of private health insurance. Other proposals would establish a public option, but retain private insurance, with wide variation across proposals in the extent to which coverage would shift from private insurance to a public plan.

Under Medicare-for-all approaches proposed by Senator Bernie Sanders (S.1129) and Representative Pramila Jayapal (H.R.1384), all U.S. residents would be covered under a public program that provides comprehensive benefits, with no premiums or cost-sharing requirements. Both Medicare-for-all bills would prohibit employers and private health insurers from offering coverage that duplicates Medicare-for-all covered benefits. The bills would permit supplemental insurance. However, because Medicare-for-all covered benefits would be comprehensive, the market for insurance to cover supplemental benefits likely would largely be limited to nursing home care, and only under the Senate bill, since the House bill covers institutional long-term care.

The Sanders Medicare-for-all bill would permit private contracting between health care providers who do not participate in the universal Medicare program and patients, and allow private insurance to cover these costs – a practice that is generally prohibited under the House bill. As a result, under the Sanders bill, there could also be a continued role for private insurance to cover or defray the cost of care for people who can afford to privately contract for medical care. Recognizing the likely impact on the private insurance workforce, both Medicare-for-all bills would set aside 1% of all national health expenditures per year for the first five years to offset anticipated economic dislocation of private health insurance and billing industry employees.

Under another approach, Medicare for America (H.R. 2452), all U.S. residents would be covered under the public program unless they opted out for a qualified employer plan. Medicare for America would maintain a role for private insurance by allowing employers to offer qualified health plans. It would however, eliminate private insurance sold through the individual market. Individuals covered under Medicare for America would also have the option to enroll in Medicare Advantage for America plans, building on the private insurance approach permitted under the current Medicare program. Today, for example, Medicare Advantage plans are offered in most, though not all, counties in the US.

Other proposals on the pathway to universal coverage would establish a public plan option and leave the current private health insurance system largely intact. The implications for private insurance would vary depending on a number of factors. For example, proposals that allow employers to choose to cover their employees under the public program would be more likely to diminish the role of private insurance than proposals that limit eligibility to people buying their own insurance. Likewise, proposals that allow employees in firms that offer group coverage to opt instead for the public plan could shift the balance between public and private insurance, particularly if such employees are eligible for subsidies under the public plan.

Several candidates running in the 2020 presidential race have addressed the role of private insurance in one way or another. In addition to the Sanders’ Medicare-for-all approach, co-sponsored by several presidential candidates, others have introduced proposals that would retain a role for private insurance while establishing a new public program or public plan option. Senator Kamala Harris’ new proposal would also establish a Medicare-for-all program, but it would allow private insurers to offer plans, modeled on Medicare Advantage, through the public program, and allow employers to provide a private Medicare plan to their employees. Former Vice President Joe Biden’s proposal would build on the architecture established by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to create a government-sponsored public plan option available to employees, those in the individual market, and those currently in the Medicaid coverage gap, while retaining job-based coverage, Medicare and Medicaid. Other candidates, such as Senator Michael Bennet would create a new public plan option that would be available only to people who get their insurance through the ACA Marketplaces, alongside other private insurance options.

The level of provider payment rates used by the public plan could also influence the distribution of public and private insurance, and the competitiveness of private insurance against the new public option. All other things equal, if provider payment rates were lower under the public plan than under private insurance, then the public plan would be expected to have lower premiums – assuming similar benefits and no selection effects.

Consumer Experiences with Private Health Insurance

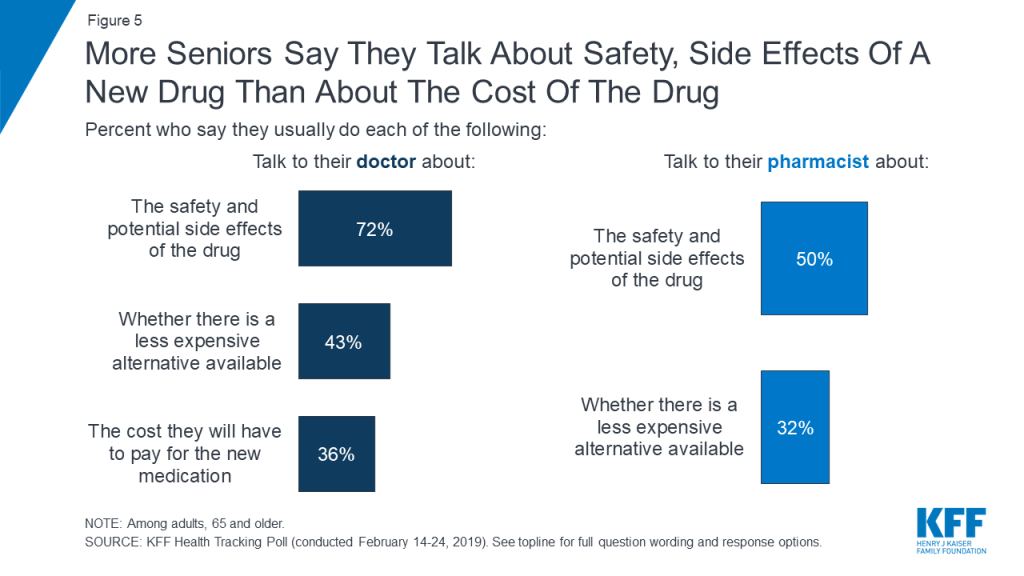

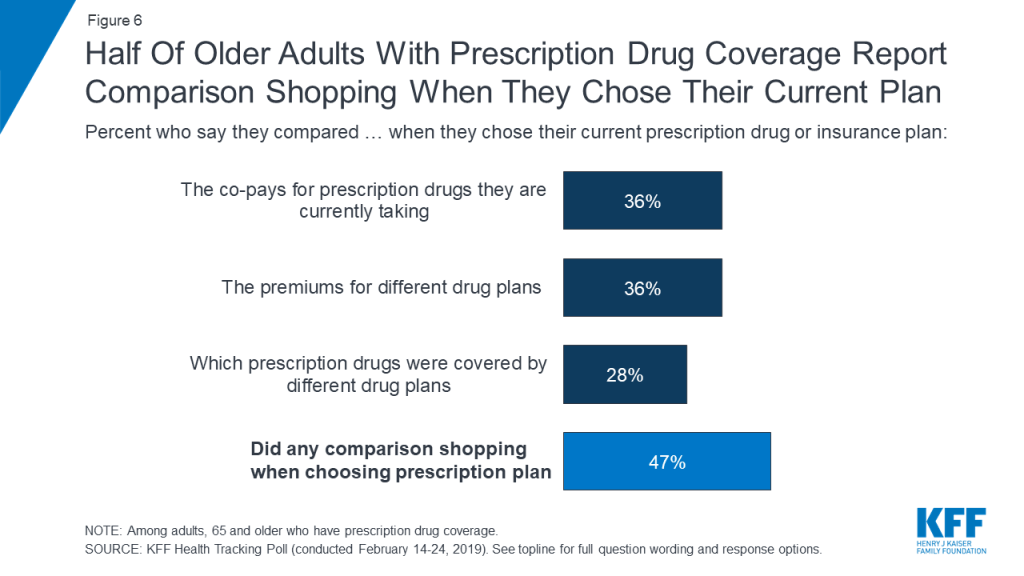

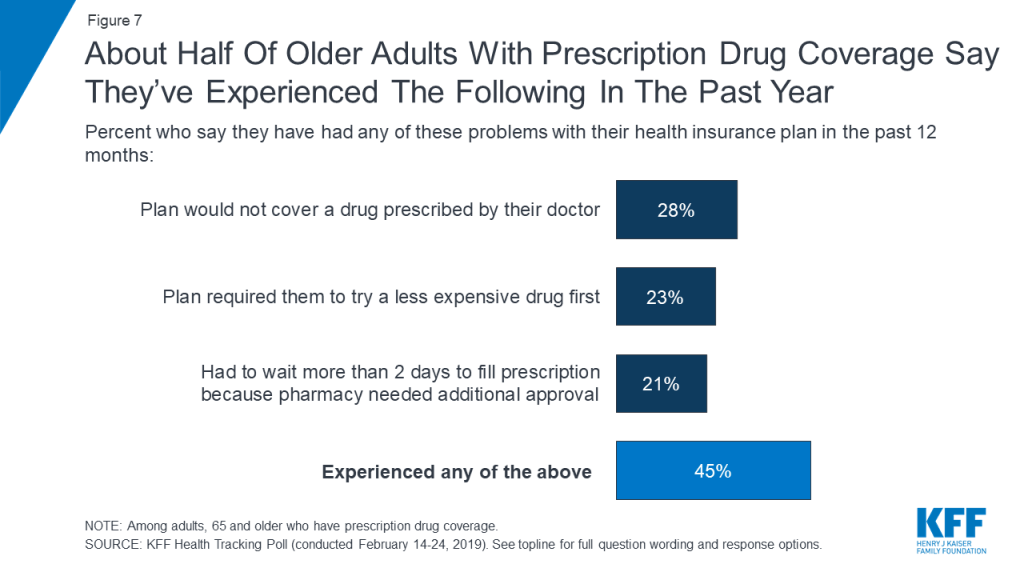

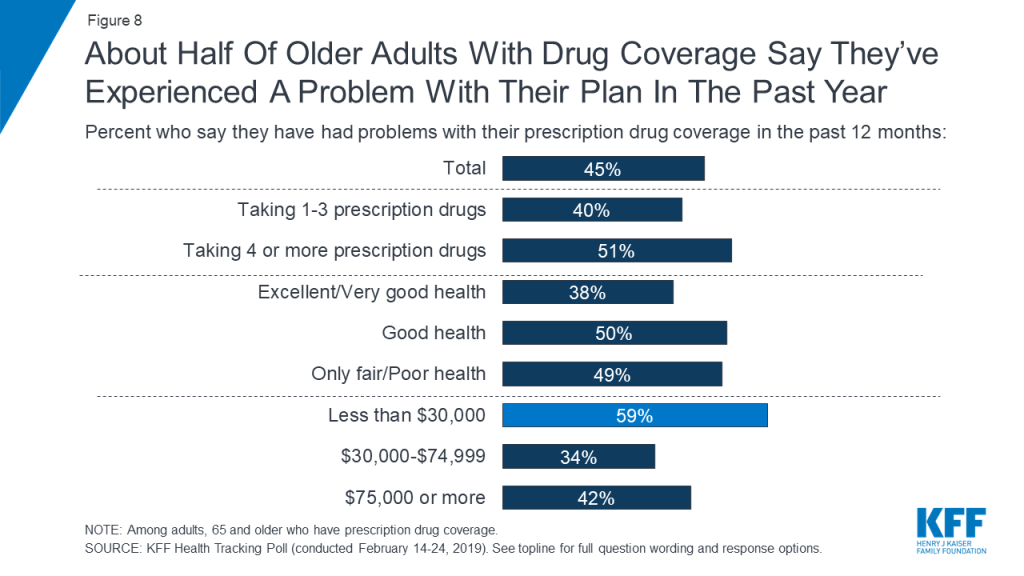

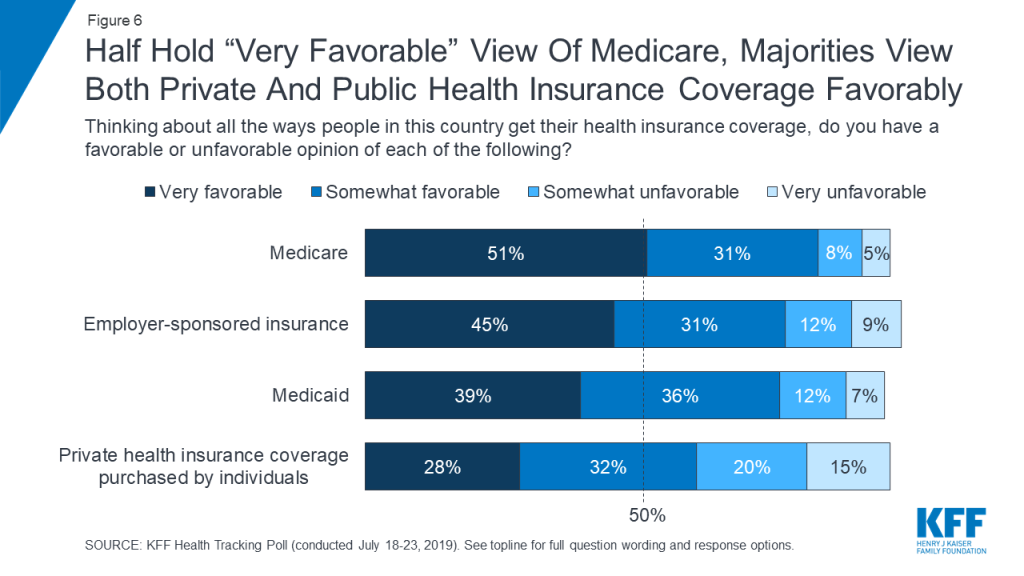

In general, the public reports relatively high rates of satisfaction with their health insurance coverage, both in private insurance and public programs. At the same time, surveys and other studies document problems encountered by people that are somewhat unique to private insurance, relating to high cost-sharing, narrow provider networks, surprise medical bills, and lack of continuity of coverage. Because Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care plans are highly regulated, relatively speaking, these issues tend to be more prominent in employer and individually-purchased coverage. These issues also tend to disproportionately affect people in relatively poor health with significant medical care needs, who use their insurance more, and people with modest incomes and limited resources to cover unanticipated expenses.

- High deductibles — High deductibles and other cost-sharing requirements have become prevalent in private health plans offered by employers and in the non-group market. For employer plans, in 2018 the average single deductible was $1,573 for those who have one, and 26% of covered workers were in plans with deductibles of $2,000 or higher. Deductibles in job-based health plans have risen at eight times the rate of workers’ earnings in the past decade. In the non-group market, nearly all ACA Marketplace plans have deductibles of $1,000 or higher, although half of all consumers who buy non-group coverage through the ACA Marketplaces qualify for cost-sharing subsidies.–Consumers in high-deductible health plans are more likely to experience problems paying their out-of-pocket medical bills and are less satisfied with their coverage. According to a recent KFF/LA Times survey, two-thirds of consumers in high-deductible job-based plans say they could not pay a bill equal to their deductible at all or without borrowing or going into debt. Among people in employer plans with the highest deductibles, over half (55%) give their plan a grade of C or lower. And, 40% of people with employer coverage say they or someone in their family experience one or more health care affordability challenges in the last year.–High deductibles are not generally a feature of Medicare Advantage plans; however, in traditional Medicare, the Part A deductible is $1,364 per benefit period, the Part B deductible is $185 and the standard Part D deductible is $415 in 2019, although some Part D plans have lower or no deductibles. Deductibles are not permitted in Medicaid.

- Provider networks – Private health plans typically create networks of providers to negotiate the prices they pay. In PPO plans, patients pay lower cost-sharing if they receive care from network providers. In HMO plans, patients can only see network providers.–Unlike traditional Medicare, which includes virtually all doctors and hospitals, private plans generally exclude some or many providers in an area, and may offer employers and non-group purchasers choices of more or less restrictive network options. Networks with fewer available providers may have lower costs (because insurers can bargain more aggressively on the terms of inclusion), but also reduce patient provider choice at the point when they need care. The use of provider networks, which is necessary to make private insurance work, creates some issues for enrollees, including limited choice of providers, disruption of care continuity if an enrollee changes plans (and networks) or a provider leaves the network, and surprise medical bills (discussed more fully below).–Medicare Advantage plans are subject to federal minimum standards with respect to provider network adequacy, but many have limited provider networks. On average, Medicare Advantage plan physician networks included less than half (46%) of all physicians in a county, and about one in three (35%) Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans with narrow physician networks; one in six Medicare Advantage plans had narrow or ultra-narrow hospital networks.With respect to Medicaid MCOs, federal rules require that states establish network adequacy standards. States have a great deal of flexibility to define those standards. Medicaid MCOs may use narrow networks but must comply with established network adequacy standards.

- Surprise medical bills – In any type of network plan, patients sometimes receive care from hospitals and doctors they do not choose and are not in their plan’s network. So-called surprise medical bills can arise in emergencies—18% of emergency claims by people covered under large group health plans involved at least one out-of-network bill. However, planned care can also involve surprise bills, such as when a pregnant woman chooses to deliver at an in-network hospital, but the on-call anesthesiologist is out-of-network—16% of in-network hospital claims by people covered under large group health plans involved at least one out-of-network bill.–While people with private insurance HMOs can be charged unlimited amounts for out-of-network care, people in Medicare Advantage HMOs who see out-of-network providers can only be charged what the provider would receive from traditional Medicare. Medicaid MCOs must adequately and timely cover services out-of-network at no more than in-network cost to enrollees, if the services cannot be provided in-network, including emergency care.

- Coverage continuity – Each month, many people lose or transition to new commercial coverage because they leave, lose, or change jobs. Even with no change in employment status, one’s group health benefits can change if an employer changes the plans it offers to employees. Disruptions in health insurance coverage can lead to disruptions in medical care, which could in turn have health consequences, lead to higher out-of-pocket costs, and cause stress for consumers.–In 2018, 61% of all firms offering health benefits shopped for a new health plan or health insurance carrier and, of those, 25% changed plans/carriers. Turnover in non-group coverage is higher. In 2016, 30% of enrollees were new to the market, and another 25% had switched from a different non-group plan the prior year. People who switch plans in the ACA Marketplaces changed coverage for a variety of reasons – for example, to find a lower premium or a plan that covered their doctor or because the prior plan was cancelled.–Medicare Advantage enrollees generally have the option of remaining covered by the same plan, switching to a new Medicare Advantage plan, or switching to traditional Medicare program during the annual open enrollment period. The majority of Medicare Advantage enrollees do not voluntarily switch plans during the open enrollment period; however, enrollees with significant medical needs, enrollees who are under age 65 with significant disabilities, and enrollees with low incomes tend to disenroll from their private plan and switch to traditional Medicare at higher than average rates.–For Medicaid, enrollees in mandatory managed care arrangements must be given a choice of at least two plans (with certain exceptions). Enrollees have the right to change plans “without cause” within 90 days of enrolling in the plan, and every 12 months thereafter, and can change plans for cause at any time. However, continuity/transition issues may occur if/when plans end their contract in a state and when enrollees move on and off the Medicaid program due to changes in income.

Discussion

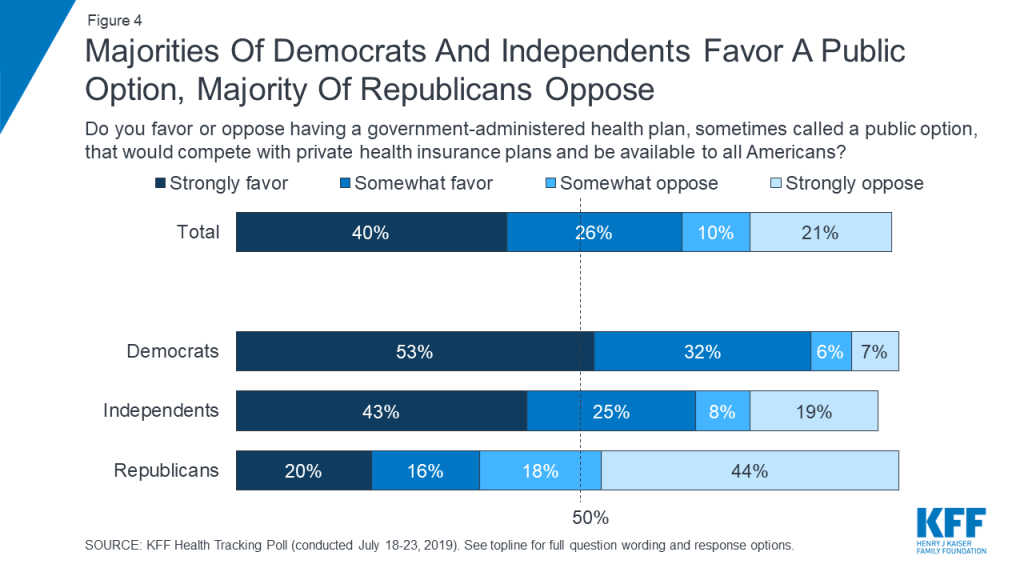

Evidence shows the public is generally satisfied with their health insurance coverage, which may explain why the question of how private insurance is treated under Medicare-for-all and public plan option proposals has become a contentious issue in the Democratic primary and influences public opinion. At the same time, there are growing concerns that people with private insurance encounter problems with their coverage, including high deductibles, surprise medical bills, narrow networks, denials, and other affordability challenges – problems that would be addressed under some Medicare-for-all proposals, as currently drafted. About half of the public support Medicare-for-all; yet, the idea of being required to give up private insurance for a new national health program clearly makes people nervous. The United States is an outlier among high-income countries in its lack of universal coverage. However, even in countries that have achieve universal coverage through some form of single-payer health care system, there is typically a role for private insurance in providing supplemental coverage.

Today, there is broad support among Democratic presidential candidates for expanding access to public health insurance programs, like Medicare. Some favor a new Medicare program that will replace most or all current private coverage and promise affordability and coverage continuity that private insurance today does not always deliver, with the trade-off of higher taxes and substantial disruption to the current system. Others favor a new Medicare option that can offer advantages over private insurance but not eliminate private coverage altogether, requiring less new federal spending but also continued premiums and cost sharing for many. As the debate continues, it remains to be seen how effectively candidates and other advocates can educate the public about the specifics of their proposals and about the relative merits of providing health coverage through a public plan versus a system of competing public and private plans, and how well voters will come to understand the trade-offs involved.