How Can Medicaid Enhance State Capacity to Respond to COVID-19?

Issue Brief

As a source of coverage for 1 in 5 Americans, Medicaid can play a key role in connecting individuals to testing and treatment for COVID-19. Through Medicaid, states can provide enrollees access to comprehensive benefits with limited out-of-pocket cost and receive federal funding with no pre-set limit to support coverage. States have options available under existing rules to expand access to coverage and facilitate enrollment in coverage for eligible individuals. Further, states can seek federal approval for additional flexibility to expedite access to coverage and care, as has occurred in response to previous disasters and emergencies. Moreover, the federal government could take a range of administrative and legislative actions to enhance state capacity to connect individuals to care through Medicaid.

This brief describes a range of steps states and the federal government could take to use Medicaid to expand coverage and access to care in the context of responding to COVID-19 as a public health crisis. The Appendix lists specific examples of Medicaid authorities available to states in emergencies. The strategies included here are not an exhaustive list of options, and, as with any such efforts, they could involve tradeoffs and may run counter to efforts by the Trump administration and some states to restrict eligibility, limit government spending, promote program integrity, and curb immigrant use of public programs. The Medicaid and CHIP Disaster Preparedness Toolkit for state agencies also specifies strategies states can implement to respond to emergencies and disasters. Moreover, on March 12, 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) posted Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) to aid state Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program agencies in their response to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Medicaid’s existing coverage and financing structure enables states to provide access to comprehensive care.

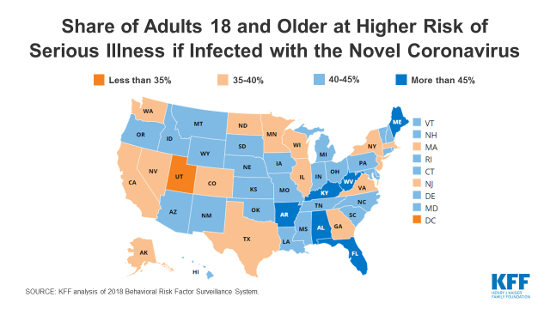

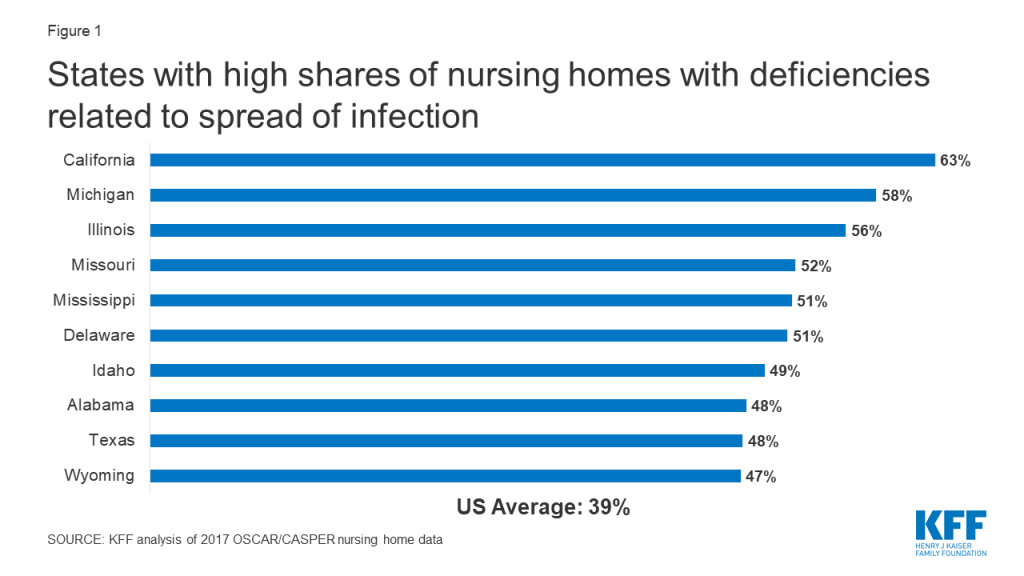

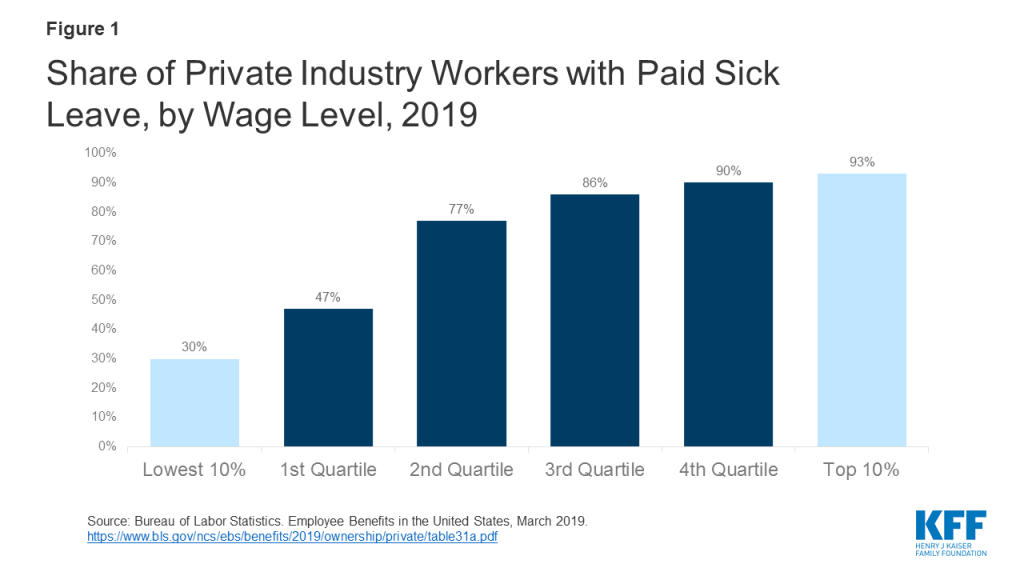

Broad source of coverage for the low-income population. As the nation’s public health insurance program for people with low income, Medicaid can be a primary vehicle through which states can connect individuals to testing and treatment for COVID-19, particularly those with significant health needs who are at high risk for experiencing complications from the virus. While most adults on Medicaid are working, the vast majority of enrollees lack access to other affordable health insurance. Medicaid plays a particularly significant role for populations with complex health needs, covering 47% of children with special health care needs, 45% of nonelderly adults with disabilities, and more than six in ten nursing home residents. Unlike other types of insurance, there are no set open enrollment periods for Medicaid, meaning that people can enroll at any time they become eligible, for example, if they experience a decrease in income due to a decline in the economy. Moreover, under law, the program provides retroactive coverage for covered services incurred up to three months prior to an enrollee’s application date if the individual would have been eligible at the time they received the service.

Comprehensive benefits. Through Medicaid, states can provide enrollees access to a broad array of services to address testing and treatment needs. States determine their Medicaid benefit package within a set of federal minimum standards and state options. All states offer at least some optional benefits, including prescription drugs. States can choose to add optional services to expand the scope of covered services to address emerging health needs. For example, in recent years, states have added an array of behavioral health and substance use disorder treatment services to address the opioid crisis. In its FAQs, CMS notes that states could expand coverage for telehealth and other services to provide care for individuals who are quarantined or self-isolated. For children, the federal minimum Medicaid benefit package offers access to all necessary services (regardless of whether these services are optional for adults) through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, which includes regular screenings, vision, dental, and hearing services and any other medically necessary care. For adults, minimum benefits include physician, inpatient and outpatient hospital, as well as laboratory services. In its FAQs, CMS clarifies that testing for COVID-19 is covered as mandatory laboratory service as long as it is provided in an office or similar facility other than a hospital outpatient department or clinic and furnished by a lab meeting specified standards. It further notes that tests that do not meet these criteria may still be covered under the optional diagnostic benefit.

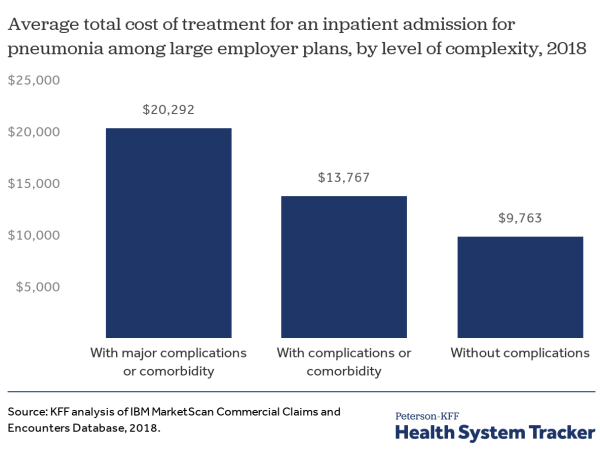

No or limited out-of-pocket costs. Medicaid provides enrollees access to services with no or limited out of pocket costs. Federal rules do not require states to charge any premiums or cost sharing for Medicaid, and limit the amounts that state can charge given enrollees’ limited ability to pay out of pocket costs. As of January 2019, only two states charged copayments for children in Medicaid, but most states charged cost sharing for parents and other adults. Some states have indicated that they are waiving cost sharing associated with COVID-19 testing and/or treatment.1 States could also broadly eliminate cost sharing for categories of services or eligibility groups. In public statements, federal officials have indicated insurance companies who provide coverage through Medicaid have agreed to cover all COVID-19 testing without cost sharing and to ensure treatment is full covered. However, to date, there is no official guidance on how these policies will be implemented or documenting insurers’ agreement to this statement.

Financing structure. Medicaid provides states a guarantee of federal matching payments for covered benefits provided to enrollees with no pre-set limit. The statute sets a formula to determine the share paid by the federal government (that varies based on states’ relative per capita income). Special enhanced match rates also are provided for the ACA Medicaid expansion, administration, and other services. This matching structure provides states with resources that automatically adjust for demographic and economic shifts, health care costs, public health emergencies, natural disasters and changing state priorities. As such, federal resources will automatically increase if demands for the program grow in response to COVID-19, for example, if enrollment increases due to income decreases amid an economic decline and/or if additional eligible individuals enroll in the program to access services. Medicaid also provides “disproportionate share hospital” (DSH) payments to hospitals serving many Medicaid and uninsured patients.

States can expand Medicaid eligibility to broaden access to care.

Medicaid expansion. To date, 37 states, including DC, have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion to adults with incomes up to 138% FPL. In the remaining 14 non-expansion states, eligibility levels for parents remain very low, often below half of poverty, and, with the exception of Wisconsin, other adults are not eligible regardless of their incomes. In these non-expansion states, 2.3 million poor uninsured adults fall into a “coverage gap”, with incomes above Medicaid eligibility limits but below the 100% FPL level at which Marketplace premium tax credits become available. Non-expansion states could significantly expand access to care for low-income adults by implementing the expansion and would receive enhanced federal matching dollars (currently at 90%) for this coverage. A substantial body of research shows that the ACA Medicaid expansion has expanded coverage, increased access to care and utilization, and improved various economic measures.

Optional eligibility expansions. Beyond the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, states have options available under federal rules to increase Medicaid eligibility above the federal minimum income limit of 138% FPL, at regular state match. For example, nearly all states (49) cover children with incomes up to at least 200% FPL through Medicaid and CHIP as of January 2019, including 19 states that cover children at or above 300% FPL. Similarly, the majority of states (47) extend eligibility to pregnant women beyond the federal minimum, including nearly half (22) who extend eligibility to above 200% FPL.

Optional coverage for legal immigrant children and pregnant women. Lawfully residing immigrants may qualify for Medicaid and CHIP but are subject to eligibility restrictions that require many to wait five years before they can enroll. States have an option to eliminate the five-year wait for lawfully residing immigrant children and pregnant women. Over half of states had adopted this option for children or pregnant women in Medicaid and/or CHIP. States also have the option to provide prenatal care to women regardless of immigration status by extending CHIP coverage to the unborn child, which 16 states had taken up as of January 2019.

Waivers of eligibility provisions. Currently, a number of states have received approval for and implemented waivers that allow them to operate their programs in way federal rules do not otherwise allow, for example, by charging premiums, imposing coverage lockouts periods, and/or not providing retroactive coverage. Given that such policies may restrict enrollment and access to care, states could suspend these waivers to facilitate access to services to address increased needs arising from COVID-19.

States can conduct outreach and adopt policy options to help get and keep eligible people enrolled in coverage.

Outreach and enrollment assistance. Nationwide, nearly a quarter (24%) of the 27.9 million nonelderly individuals who were uninsured as of 2018 were eligible for Medicaid or CHIP coverage but not enrolled. Previous state experience has illustrated that states can promote enrollment of eligible individuals through a combination of broad mass media outreach campaigns to raise awareness of coverage options as well as targeted local efforts, often in collaboration with community based organizations and/or safety-net providers, to provide direct enrollment assistance.

Presumptive eligibility and eligibility verification. Presumptive eligibility allows states to expedite connections to coverage by authorizing certain qualified entities, like community health centers or schools, to enroll individuals who appear likely eligible for coverage while the state processes the full application. Prior to the ACA, states could utilize this option for children and pregnant women. The ACA allowed states to adopt this option for other eligibility groups. The ACA also required states to allow hospitals to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations regardless of whether the state had otherwise adopted the policy. While most states have adopted this option for pregnant women and children, only a few currently utilize it for parents and other adults. In addition, under existing rules, states can allow for self-attestation for all eligibility criteria, excluding citizenship and immigration status, including on a case-by-case for individuals subject to a disaster when documentation is not available.

12-month continuous eligibility for children. States who elect to use this option can allow a child to remain enrolled for a full year unless the child ages out of coverage, moves out of state, voluntarily withdraws, or does not make premium payments. As such, 12-month continuous eligibility eliminates coverage gaps due to fluctuations in income over the course of the year, promoting stable and continuous access to care. As of January 2019, 32 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children in either Medicaid or CHIP. States do not have an option under federal rules to extend 12-month continuous eligibility to groups other than children, but two states (New York and Montana) have obtained waivers to provide 12-month continuous eligibility to adults.

Suspend or delay renewals. Under federal rules, states renew coverage every twelve months. States have existing authority to extend redetermination timelines for current enrollees subject to a disaster to maintain continuity of coverage. Some states have previously delayed or suspended renewals through 1115 waivers in response to emergencies. Moreover, CMS allowed states to delay or suspend renewals as a mitigation strategy when states were implementing the ACA and addressing system challenges and processing a large number of new enrollments under the Medicaid expansion.

Suspend periodic data checks between renewals. Between annual renewal periods, enrollees are required to report changes in circumstances that may affect eligibility, and states may conduct periodic electronic data matches to identify potential changes in circumstances. If a state identifies a change that may affect eligibility, it may request information or documentation from the individual to continue coverage. If the individual does not respond to a request within the required timeframe, the state will disenroll the individual from coverage. Recent reports suggest that these periodic data checks may be leading to coverage losses among eligible individuals because they do not receive or are not able to respond to information requests within required timeframes, which are limited to 10 days in many states conducting these checks. As such, suspending these data checks could help keep enrollees connected to coverage.

States can seek federal approval for additional flexibility to connect people to coverage and care.

Section 1135 waivers. If the President has declared an emergency or disaster and the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) has declared a public health emergency, the Secretary can use Section 1135 authority to waive or modify certain Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP requirements to ensure that sufficient health care items and services are available to meet the needs of Medicaid enrollees in affected areas. Examples of items that can be waived through Section 1135 authority include: conditions of participation or other certification requirements for providers; program participation and preapproval requirements for providers; requirements that physicians and other health care professionals be licensed in the state in which they are providing services (as long as they have equivalent licensing in another state for Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP reimbursement only); and the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. The Secretary used Section 1135 to provide hurricane relief to a number of areas affected by storms during 2017. On March 13, President Trump issued a proclamation that the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States constitutes a national emergency, beginning March 1, 2020. With this declaration, the administration announced steps to take to address COVID-19 through 1135 waivers.

Section 1115 waivers. Section 1115 waiver authority allows the Secretary of HHS to test new approaches in Medicaid not otherwise allowed under current law, provided the demonstrations meet the objectives of the program. During past emergencies, states obtained Section 1115 waivers to expedite access to coverage and health care services for affected individuals. These included waivers to: expand coverage to individuals not otherwise eligible (including adults who were not eligible for Medicaid prior the ACA), streamline application and eligibility verification processes, temporarily suspend or delay renewals for existing enrollees, waive cost sharing and/or expand benefits for targeted population groups, and address needs for individuals within specific geographic areas of a state. For example:

- Approximately 350,000 New Yorkers were covered by Disaster Relief Medicaid in a four-month time period following the September 11th attacks in 2001. DRM allowed for a simplified expedited application process, expanded income eligibility guidelines and adjusted immigrant eligibility rules to make more New Yorkers eligible for coverage in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. It also temporarily suspended annual renewals for many existing enrollees.

- Following Hurricane Katrina, the Department of HHS released a waiver initiative to assist states in providing temporary coverage to certain groups of evacuees. Under these waivers, states could get expedited approval to provide up to five months of Medicaid or CHIP coverage to certain evacuees and receive authorization for an “uncompensated care pool” to reimburse providers for the costs of furnishing services to uninsured evacuees and services not otherwise covered under Medicaid or CHIP (including mental health counseling). Similar to Disaster Relief Medicaid in New York, these waivers also streamlined eligibility verification criteria for the temporary coverage period.

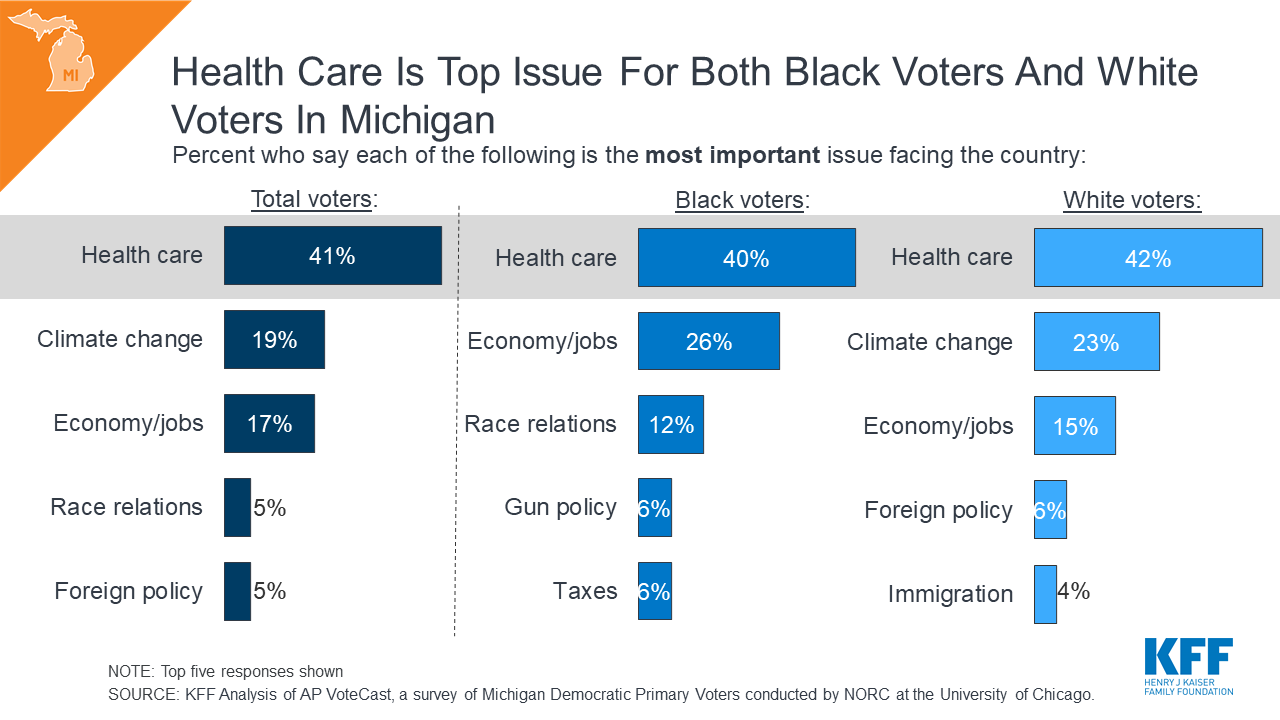

- In 2016, Michigan received a waiver to expand Medicaid and CHIP eligibility for children and pregnant women affected by the Flint water crises and to waive cost sharing and premiums and expand targeted case management benefits and community support services for these enrollees.

- Following Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Texas received approval to allow individuals in the affected service area to receive services beyond their renewal period, suspended certain eligibility verification requirements, and eliminated cost sharing for the waiver period.

The federal government could take action to enhance state capacity to provide access to care through Medicaid.

Administrative Options

Provide guidance and/or a template to facilitate state adoption of policy options. CMS posted a national fact sheet outlining coverage and benefits related to COVID-19 and posted the FAQs to aid states in determining steps they can take to enhance their response. CMS also could issue guidance and/or state plan amendment and waiver templates to facilitate states’ implementation of options to enhance access to coverage and care. For example, in 2016, CMS put out an informational bulletin with information related to optional Medicaid benefits states could adopt to help address the Zika virus. In addition, CMS recently issued a waiver template to encourage states to take up options tied to the new Healthy Adult Opportunity demonstrations.

Suspend pending regulations that would limit financing. CMS is currently reviewing comments related to the Medicaid Fiscal Accountability Rule. The rule would make changes to what funding states can use for the state share of Medicaid funding and to supplemental payments to providers. The changes could have significant implications for providers and state budgets. While the rule could reduce federal spending on Medicaid, it also creates significant uncertainty for states as they work to address COVID-19.

Suspend administrative actions focused on increasing eligibility verification requirements. As part of program integrity efforts, the Trump Administration has recently increased its focus on oversight of eligibility determinations. It has indicated plans to conduct new audits of state beneficiary eligibility determinations, promoted the use of periodic data matches between renewals, and indicated plans to issue regulatory changes to increase requirements around verification, monitoring of changes in beneficiary circumstances, and eligibility redeterminations. While current and planned administrative efforts might limit instances of ineligible people being enrolled in the program, they could also result in greater enrollment barriers and coverage losses for people who are eligible and add additional administrative burden for state agencies at a time when expediting enrollment in coverage for eligible individuals would help connect them to testing and treatment.

Suspend immigration policies that may be deterring immigrant families from enrolling in coverage and seeking care. Over the past several years, the Trump Administration has implemented a range of immigration policies focusing on restricting immigration, enhancing immigration enforcement, and restricting access to public programs, including Medicaid, for immigrant families. These include recent changes to public charge policies that newly take into account use of Medicaid by non-pregnant adults as part of the public charge test federal officials use to determine whether to grant certain individuals entry into the U.S. or adjustment to legal permanent resident (LPR) status (i.e., receive a green card). A growing set of evidence suggests that families have increased fears of enrolling themselves and their children, who are primarily U.S. citizens, in Medicaid and CHIP due to these policy changes and that some may be avoiding seeking care. The administration could take steps to alleviate these fears by suspending the changes to public charge policies. They also could take steps to assure families that they will not use any information shared to enroll in coverage for immigration enforcement purposes and that enrolling in coverage and/or seeking care will not have negative effects on their immigration status. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services issued an alert in March 2019, encouraging all individuals with symptoms that resemble COVID-19 to seek necessary medical treatment or preventive services and noted that such treatment or services will not negatively affect future public charge tests.2

Legislative Options

Enhance federal financing. During economic downturns, more people qualify and enroll in Medicaid, increasing program spending at the same time that state tax revenues may be stagnating or falling. To mitigate these budget pressures, Congress has twice passed temporary increases in the federal match rate to help support states during economic downturns, most recently in 2009 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). To receive ARRA funds, states could not roll back Medicaid eligibility. These temporary increases in the Medicaid match rate provided states fiscal capacity to address health issues for vulnerable populations through an existing, efficient mechanism. Congress could use such a mechanism to provide additional fiscal capacity for states. In addition, as providers will likely serve individuals who are uninsured or underinsured, Congress could increase funding for Medicaid disproportionate share hospital (DSH) to help reimburse hospitals for increased uncompensated care costs.

Increase access to coverage for lawfully present immigrants. As noted, lawfully residing immigrants may qualify for Medicaid and CHIP but are subject to eligibility restrictions that subject many to a five-year waiting period before they may enroll in coverage. These eligibility restrictions have been in place since 1996 under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act. The CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2009 provided states the option to cover lawfully residing immigrant pregnant women and children without a five-year waiting period, but not other groups. Congress could enact legislation to extend this option to parents and other adults.

Families First Coronavirus Response Act. Legislation enacted on March 19, 2020 will provide coverage for COVID-19 testing with no cost sharing under Medicaid and CHIP (as well as other insurers) and provide 100% federal funding through Medicaid for testing provided to uninsured individuals for the duration of the emergency period associated with COVID-19. The law will also provide states and territories a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal matching rate for the emergency period. To receive this increase, states will need to meet certain requirements including: not implementing more restrictive eligibility standards or higher premiums than those in place as of January 1, 2020; providing continuous eligibility for enrollees through the end of the month of the emergency period unless an individual asks to be disenrolled or ceases to be a state resident; and not charging any cost sharing for any testing services or treatments for COVID-19, including vaccines, specialized equipment or therapies. The law will also increase federal allotments to the territories.

Appendix

| Table 1: Medicaid Authorities Available in Emergencies |

| Allowed by Existing Regulations |

|

| Amended/Updated Verification Plan – No CMS Approval Required |

|

| State Plan Amendment – Can be Retroactive to 1st Day of Quarter |

Coverage:

|

| Health Plan Contract/Oversight |

|

| Section 1115 Waiver – state is deemed to meet budget neutrality if federally declared disaster, waiver can be retroactive to date of Secretary-declared public health emergency, exemptions from public notice in emergencies |

Coverage:

Enrollment & Renewal:

Benefits:

Long-Term Services and Supports:

|

| Section 1135 Waiver – if President declares national emergency and HHS Secretary declares public health emergency |

Benefits:

Long-Term Services and Supports:

Appeals:

|

| Section 1915 (c) Home and Community-based Services Waiver Appendix K – can be submitted before or during emergency, can be retroactive to date of event |

Eligibility:

Benefits:

Providers:

|

| SOURCES: CMS, COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions for State Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Agencies (March 12, 2020); Medicaid and CHIP Coverage Learning Collaborative, Disaster Preparedness Toolkit for State Medicaid Agencies (Aug. 20, 2018); Medicaid and CHIP Coverage Learning Collaborative, Inventory of Medicaid and CHIP Flexibilities and Authorities in the Event of a Disaster (Aug. 20, 2018); CMS, 1915 (c) Home and Community-Based Services Waiver Instructions and Technical GuidanceAPPENDIX K: Emergency Preparedness and Response. |

Endnotes

- See for example: “Governor Murphy Announces Efforts to Support Consumer Access to COVID-19 Screening, Testing, and Testing-Related Services”, State of New Jersey, accessed March 12, 2020, https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/20200310a.shtml; “Governor Cuomo Announces New Directive Requiring New York Insurers to Waive Cost-Sharing for Coronavirus Testing”, New York State, accessed March 12, 2020, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-new-directive-requiring-new-york-insurers-waive-cost-sharing; “Gov. Whitmer announces Michigan medicaid will waive co-pays for COVID-19 testing”, WZZM13, accessed March 12, 2020, https://www.wzzm13.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/governor-whitmer-announces-copay-price-waive-for-coronavirus-testing-in-michigan/69-9e7e7363-08a3-4d4d-98db-0687e442e8f7. ↩︎

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Public Charge,” https://www.uscis.gov/greencard/public-charge, accessed March 16, 2020. ↩︎