KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: COVID-19 Vaccine Access, Information, and Experiences Among Hispanic Adults in the U.S.

Findings

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project tracking the public’s attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and qualitative research, this project tracks the dynamic nature of public opinion as vaccine development and distribution unfold, including vaccine confidence and acceptance, information needs, trusted messengers and messages, as well as the public’s experiences with vaccination.

Key Findings

- The latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor report highlights the disproportionate toll the pandemic has taken on Hispanic adults in the United States. Hispanic adults, particularly those who mainly speak Spanish, were born outside the U.S., or who have lower incomes, are more likely than White adults to say someone close to them has gotten sick from COVID-19 or that they worry about someone in their family getting sick and more likely to say the pandemic has negatively affected their financial situation. At a time when many are facing growing financial needs, one in ten (11%) Hispanic adults, rising to one-quarter (26%) of those who are potentially undocumented, say there was a time in the past 3 years when they or a family member decided not to apply for or stopped participating in a government assistance program that helps with food, housing, or health care because they were afraid it might negatively affect their or a family member’s immigration status.

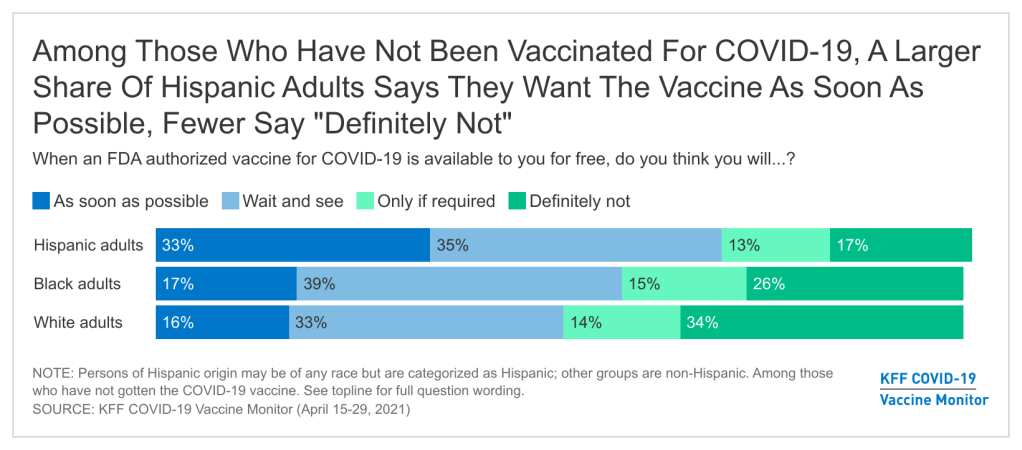

- Among those who have not yet been vaccinated, Hispanic adults are about twice as likely as White adults to say they want to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible, indicating an opportunity for more focused outreach and information efforts. While nearly half (47%) of Hispanic adults report having received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, one-third of unvaccinated Hispanic adults say they want a vaccine as soon as possible, about twice the share as among unvaccinated Black and White adults. By contrast, unvaccinated Hispanic adults are half as likely as unvaccinated White adults to say they will “definitely not” get the vaccine (17% vs. 34%).

- Large shares of Hispanic adults – particularly those with lower incomes, the uninsured, and those who are potentially undocumented – express concerns that reflect access-related barriers to vaccination. Compared to White adults, larger shares of unvaccinated Hispanic adults say they are concerned about missing work due to vaccine side effects, that they might have to pay out of pocket for the vaccine (despite it being free), not being able to get the vaccine from a trusted place, or having difficulty traveling to a vaccination site. Among Hispanic adults, the shares expressing many of these concerns are even greater among those with lower incomes, the uninsured, and those who are potentially undocumented.

- Requests for documentation may pose a barrier to vaccination for some Hispanic adults, particularly those who live in immigrant families. Over half of Hispanic adults (56%) who have been vaccinated say they were asked to provide a government-issued identification when they received their vaccine and 15% say they were asked to provide a Social Security number. While eligibility to receive a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S. is not linked to immigration status, requests for these types of information or documents may be a deterrent for some Hispanic adults, particularly those in immigrant families. In fact, about four in ten unvaccinated Hispanic adults (rising to 58% of those who are potentially undocumented) say they are concerned that they may be required to provide a government-issued identification or Social Security number to get vaccinated, and about one third (rising to 63% of the potentially undocumented) are concerned that getting the vaccine may negatively affect their own or a family member’s immigration status.

- There are gaps in information about who is eligible for the vaccine and how to get it among the Hispanic population. Large shares of unvaccinated Hispanic adults, particularly those who are potentially undocumented, are unsure if they are eligible to get a vaccine or say they don’t have enough information about when or where to get one. At least half are unaware that the vaccines are free for all U.S. residents and that all adults are eligible regardless of immigration status.

- Making COVID-19 vaccines available in more convenient locations, providing paid time off to recover from side efforts, or requiring vaccination for travel may be more effective at encouraging vaccine uptake among Hispanic adults compared to others. Almost half of unvaccinated Hispanic adults who are not yet ready to get the vaccine right away say they’d be more likely to get vaccinated if the vaccine was offered at a place they normally go for care, and four in ten of those with jobs say they’d be more likely to get it if their employer arranged for it to be delivered at their workplace, both higher than the shares of White adults who say the same. Over half of employed, unvaccinated Hispanic adults who are not yet ready to get the vaccine say they’d be more inclined to get it if their employer gave them paid time off to get vaccinated and recover from side effects. Requiring the vaccine for airline or international travel may be particularly effective at encouraging foreign-born Hispanics the vaccine, with about six in ten saying such requirements would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a stark disproportionate toll on people of color, including the Hispanic population. Hispanic people have faced increased risk of exposure to the virus as many are employed in essential jobs that cannot be done from home and live in larger, multigenerational households. Reflecting these increased risks, Hispanic people have suffered higher rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death compared to their White counterparts. Despite being harder hit by the pandemic, Hispanic people have been less likely than White people to receive a COVID-19 vaccine so far. These disparate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have exposed and exacerbated longstanding underlying disparities in health and health care facing Hispanic people. Prior to the pandemic, these disparities had already been compounded by immigration policies implemented during the Trump administration that increased fears among immigrant families and made some more reluctant to access programs and services, including health coverage and health care. Although the Biden administration has since reversed many of these policies, they may continue to have lingering effects among families.

This report from the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is based on interviews with 778 Hispanic adults in the U.S., including 334 conducted in Spanish and 408 with adults born outside the U.S., including 185 who indicated that they do not have lawful permanent resident status (referred to in this report as “potentially undocumented”).1 It provides insights into how Hispanic adults have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and their access, information, and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Moreover, it illustrates the varied experiences within the Hispanic population, including describing the experiences of Hispanic immigrants, for whom data remain limited. Throughout this report, Hispanic adults include people of any race, other groups (i.e., White and Black adults) are non-Hispanic.

COVID-19 Impacts on Hispanic Adults in the U.S.

The survey findings reveal that Hispanic adults have substantial fears about getting sick from coronavirus, and that many have close connections to people who have gotten sick or died from COVID-19. They also highlight the widespread negative financial impacts of the pandemic for Hispanic adults. In addition, they provide insight into how immigration-related fears may be affecting Hispanic adults’ willingness to participate in assistance programs for food, housing, and health care, at a time when many have growing needs due to the financial impacts of the pandemic.

About two-thirds of Hispanic adults say they are worried that they or someone in their family will get sick from coronavirus, including 41% who say they are very worried. The share saying they are very worried is higher among Hispanic adults than among Black adults (30%) and is four times the rate among White adults (10%). Worries about getting sick from coronavirus are even more prevalent among Hispanic immigrants, particularly those without permanent resident status. Seven in ten (69%) of potentially undocumented Hispanic adults say they are very worried about themselves or a family member getting sick from COVID-19 as are over half (57%) of foreign-born Hispanic adults with permanent resident status. Among U.S.-born Hispanic adults (who are much younger on average than their foreign-born counterparts), one quarter (24%) express this level of worry. There also are stark differences in levels of concern among Hispanic adults by language spoken and household income, with nearly three in four (73%) of Hispanic adults who completed the survey in Spanish and over half (53%) of those in lower income households reporting being very worried about getting sick.

This higher level of worry is not unfounded, as Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to report close connections to someone who has gotten sick or died from coronavirus. Nearly three in ten (28%) of Hispanic adults say they or someone in their household has tested positive for coronavirus, higher than the shares of Black (21%) and White adults (18%). This share rises among Hispanic adults born outside the United States, including 40% of the potentially undocumented. About four in ten (38%) Hispanic adults say a close friend or family member has died from coronavirus, similar to the 34% among Black adults and higher than the 18% among White adults. There were no major differences in the likelihood of having a close friend or family member die by immigration status.

The pandemic has also taken a disproportionate financial toll on Hispanic families in the United States. About half (48%) of Hispanic adults say the pandemic has had a negative effect on their personal financial situation, higher than the share of White adults who say the same (36%). Among those with lower household incomes (under $40,000 per year), 56% of Hispanic adults say their financial status has been negatively affected by the pandemic, higher than the shares among lower-income Black or White adults (42% each). There were no major differences in the likelihood of reporting negative financial effects by immigration status. However, a 55% majority of Hispanic adults who completed the survey in Spanish say their financial situation has been negatively impacted by the pandemic, higher than the four in ten (43%) of English-speaking Hispanic adults who report being negatively affected.

Some Hispanic adults, particularly those who are potentially undocumented, report that they have avoided seeking assistance for food, housing, and/or health care due to immigration-related fears. The Trump administration implemented a range of immigration policy changes, including changes to public charge policy, that increased fears among immigrant families and made some more reluctant to access programs and services, including health coverage and care. While the Biden administration has since reversed many of these policies, they may continue to have lingering effects among families at a time when many are facing growing needs due to the pandemic.

Overall, one in ten Hispanic adults (11%), say there was a time in the past 3 years when they or a family member decided not to apply for or stopped participating in a government assistance program because they were afraid it might negatively affect their or a family member’s immigration status. Across Hispanic adults overall, 6 percent say they did not apply for or stopped participating a program to help with food, 4 percent say assistance for housing, and 3 percent say a health care program.

The share saying they or a family member did not apply for or stopped participating in a program in the past 3 years due to immigration-related fears increased rises to 26% among potentially undocumented Hispanic adults. Among potentially undocumented Hispanic adults, 21% say they did not apply for or stopped participating a program to help their family with food, 12 percent say assistance for housing, and 11 percent say a health care program. While undocumented immigrants generally are not eligible for any federally-funded assistance, many live in mixed immigration status families, including other family members such as U.S.-born citizen children, who may qualify for assistance.

COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions Among Hispanic Adults

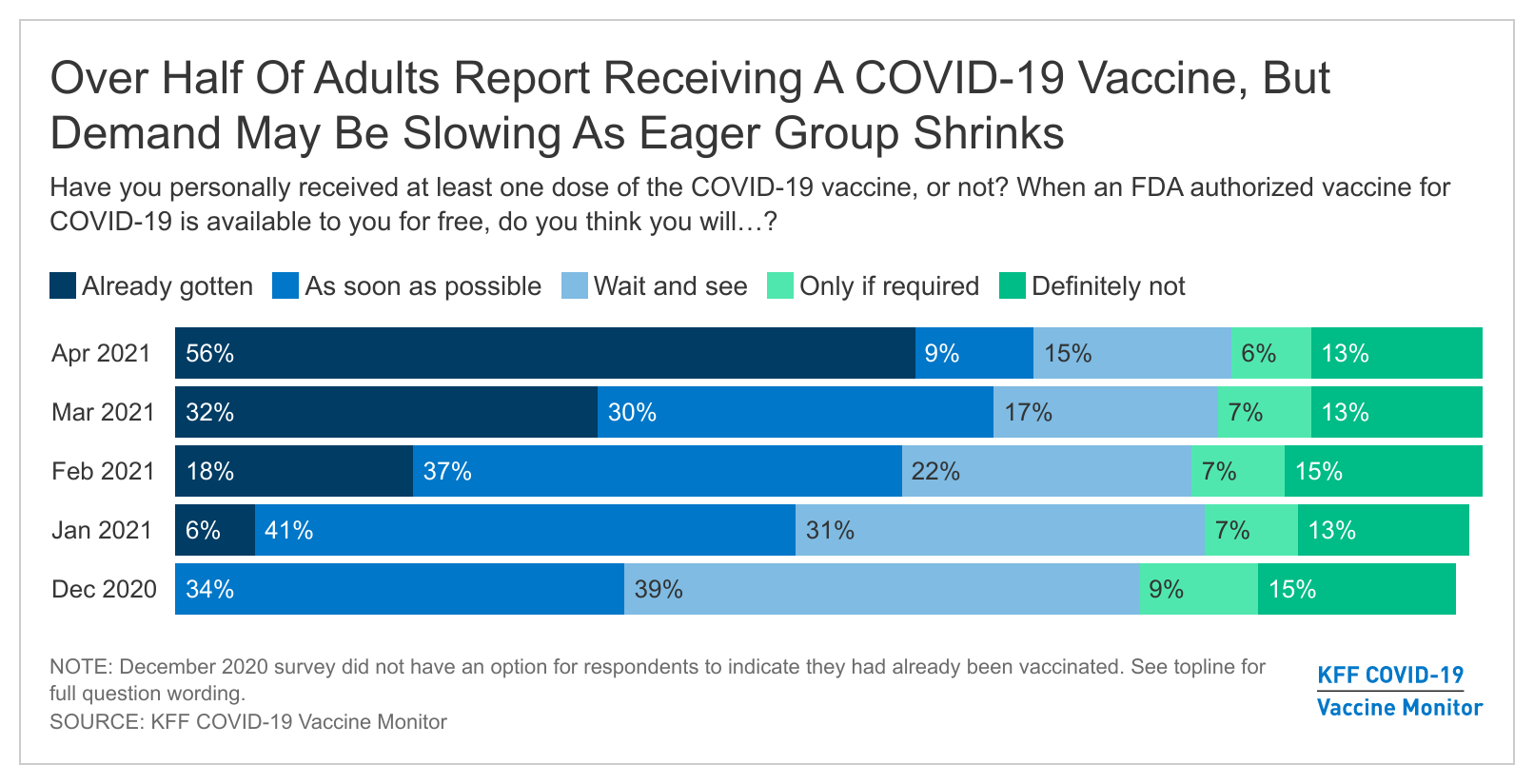

Nearly half (47%) of Hispanic adults say they have already received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and another 17% say they intend to get one as soon as they can. The share of Hispanic adults who say they’ve received at least one dose of the vaccine is lower than the share among White adults (60%), while a larger share of Hispanic adults compared to White adults say they will “wait and see” how the vaccine is working for other people before getting vaccinated themselves (18% vs. 13%). Nearly one in five (17%) Hispanic adults report that they have not yet been vaccinated but want to get one as soon as possible, higher than the shares among White adults (6%) and Black adults (9%).

Among those who have not yet been vaccinated, Hispanic adults are twice as likely as White adults to say they want to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as they can, making them a key target for outreach and information. Looking just at those adults who have not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine, one-third of Hispanic adults say they want to get one as soon as they can compared to 16% of White adults and 17% of Black adults. By contrast, larger shares of unvaccinated White and Black adults compared to Hispanic adults say they will definitely not get a COVID-19 vaccine (34%, 26%, and 17%, respectively).

Some groups of Hispanic adults are more likely to say they have not yet gotten the vaccine but want to get one as soon as possible, suggesting they are particularly likely to face access barriers to getting the vaccine. For example, three in ten (31%) of potentially undocumented Hispanic adults report having gotten a COVID-19 vaccine, and nearly four in ten (37%) want one as soon as possible but haven’t yet gotten one. This finding is similar for uninsured nonelderly Hispanic adults, with about three in ten (29%) of this group reporting receiving the vaccine and another 30% wanting one as soon as possible. Adults who completed the survey in Spanish are also more likely than English speaking adults to say they want a vaccine as soon as possible, but this largely reflects a higher share of English-speaking Hispanic adults saying that they do not plan to get the vaccine.

Among Hispanic adults, divides in COVID-19 vaccination intention by age, education, and partisanship mirror those seen in the general population. Large majorities of Hispanic adults ages 50 and over say they’ve already gotten at least one dose of the vaccine or will do so as soon as possible (85% of those ages 50-64 and 88% of those ages 65 and over). By contrast, larger shares of younger Hispanic adults say they want to wait and see how the vaccine is working (20% of those ages 30-49 and 31% of those ages 18-29). Similarly, Hispanic adults who identify as Democrats or lean that way are much more likely than those who identify or lean Republican to say they have either gotten a vaccine or will do so as soon as they can, while Republicans are more likely to say they will definitely not get vaccinated. Hispanic adults with a college degree are more likely than those with lower levels of education to say they’ve already gotten a COVID-19 vaccine (61% vs. 45%), while those who are not college graduates are more likely to say they have not been vaccinated but want to do so as soon as possible (18% vs. 10%), suggesting possible access barriers for this less-educated group, similar to the groups mentioned above.

Hispanic Adults’ Experiences Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine

Among those who report receiving a COVID-19 vaccine, Hispanic adults are more likely than White and Black adults to report getting their vaccine through a community health clinic. The most common place people report receiving a COVID-19 vaccine across race and ethnicity groups is a large vaccination site. At least one-third of those who have received at least one dose of a vaccine reporting receiving it there (35% of vaccinated Hispanic adults, 37% of Black adults, and 35% of White adults). Consistent with other analysis showing community health centers are vaccinating larger shares of people of color, particularly Hispanic people, over one in five (22%) vaccinated Hispanic adults reported getting their vaccine at a community health clinic, twice the share of White (11%) and Black (10%) vaccinated adults who report the same. Among Hispanic adults, 30% of those who completed the interview in Spanish say they got vaccinated at a community health clinic compared to 17% of those who completed the interview in English. There were no significant differences in the share of Hispanic adults getting vaccinated at a community health clinic by immigration status or income.

Hispanic adults are less likely than White adults to report signing up for a vaccine appointment online. Among those who have gotten a vaccine or have tried to get an appointment, about half of Hispanic adults (48%) either signed up or tried to do so online compared to nearly six in ten White adults (58%). A quarter (25%) of Hispanic adults say they signed up or tried to sign up by phone, and another 16% scheduled or sought to schedule an appointment in person.

Many Hispanic adults report being asked for certain types of information or documentation when they signed up for or received a vaccine that may pose barriers to getting the vaccine for some. The COVID-19 vaccines are available for free regardless of insurance status. Some vaccine providers request health insurance information from people receiving the vaccine in order to bill for the cost of administering the vaccine, which may lead some people to be confused about whether uninsured people can get the vaccine or if they have to pay to receive one. The federal government has also clarified that vaccines are available to individuals regardless of immigration status. Despite this, requests for information and/or documentation to provide proof of identity or residency may vary across states, localities, and vaccination providers. For example, in some cases, individuals are being requested to provide government-issued identification or a Social Security number, while others provide a range of options to prove identity or residency, including self-attestation, and specify that a Social Security number is not required.

Among all Hispanic adults who made or attempted to make an appointment to receive a vaccine, about a third (32%) report being asked to provide health insurance information when making an appointment. Four in ten (42%) say they were asked to provide a government-issued identification and 14% say they were asked to provide a Social Security number. Among those who have been vaccinated for COVID-19, over half (56%) say they were asked for their ID at the vaccination site, 23% were asked for insurance information and 15% report being asked to provide a Social Security number.

Potential Barriers To COVID-19 Vaccination Among Hispanic Adults

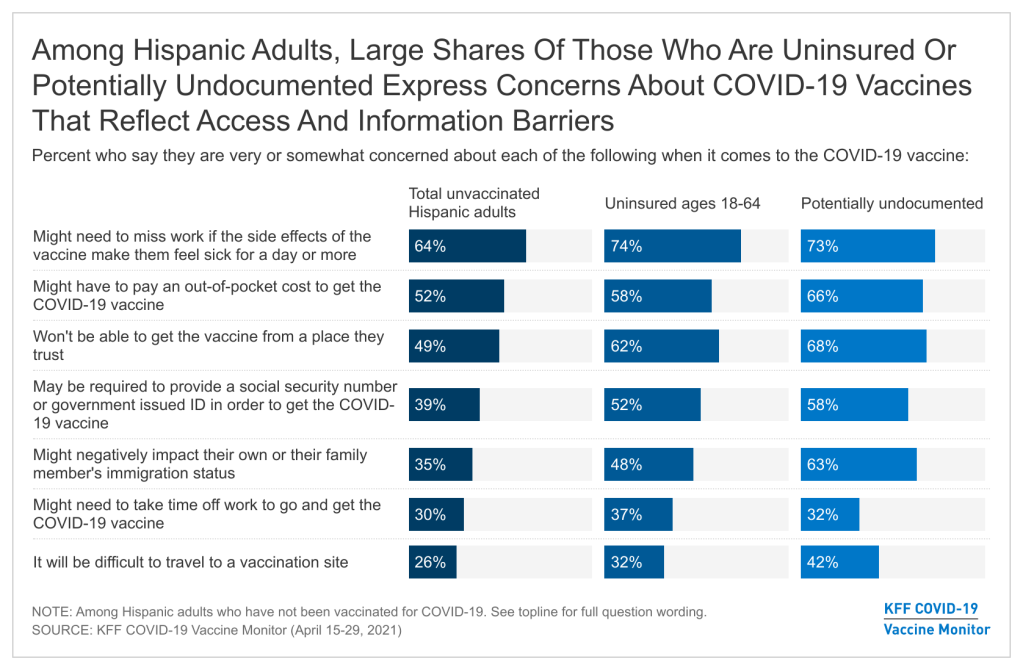

Hispanic adults who have not yet been vaccinated for COVID-19 are more likely than White adults to express concerns that reflect access-related barriers to vaccination. Although potential side effects and vaccine safety are the top-ranked concerns among Hispanic adults who have not yet been vaccinated for COVID-19, many also report concerns related to potential challenges getting the vaccine. Among unvaccinated Hispanic adults, nearly two-thirds (64%) are concerned about missing work due to side effects, over half (52%) are worried they might have to pay out of pocket for the vaccine, and nearly half are concerned they won’t be able to get the vaccine from a place they trust (49%), shares that are significantly larger than their White counterparts.

Notably, among Hispanic adults who say they have not yet been vaccinated but want to do so right away, six in ten are concerned that they won’t be able to get the vaccine from a place they trust (61%) or that they might have to pay an out-of-pocket cost to get the vaccine (59%) and half (52%) are concerned about missing work due to vaccine side effects, highlighting that access remains a barrier even for those in the most eager group.

Because the Hispanic population includes higher shares of noncitizens compared to other groups, immigration-related concerns may also particularly affect this population. Four in ten unvaccinated Hispanic adults (39%) are concerned they might be required to provide a Social Security number or government-issued identification in order to get vaccinated, and just over a third (35%) are concerned that by getting the COVID-19 vaccine they might negatively affect their own or a family member’s immigration status.

Among unvaccinated Hispanic adults, those who are potentially undocumented, those without health insurance, and those with lower household incomes are more likely to express potential access-related barriers or immigration-related concerns to vaccination. The top access-related concern across these groups is that they might have to miss work due to side effects. Not surprisingly, potentially undocumented Hispanic adults are particularly concerned they may need to provide a Social Security number or government issued ID to get the vaccine (58%), and nearly two thirds (63%) are concerned getting the vaccine might negatively affect their or a family member’s immigration status.

In addition, unvaccinated Hispanic adults who are uninsured are more likely than those who have health insurance to say they are concerned about not being able to get the vaccine from a place they trust, being required to provide a Social Security number or government-issued ID, or negatively impacting their own or a family member’s immigration status.

Compared to their higher-income counterparts, unvaccinated Hispanic adults with incomes under $40,000 a year are more likely to say they are concerned about missing work due to COVID-19 vaccine side effects, having to pay an out-of-pocket cost to get vaccinated, negatively affecting someone’s immigration status, and having difficulty traveling to a vaccination site.

Strategies that address access-related concerns may be particularly effective for increasing enthusiasm to get the COVID-19 vaccine among Hispanic adults. For example, nearly half of Hispanic adults who have not gotten the vaccine and are not ready to get it right away (46%, rising to 64% among those born outside the U.S.) say they’d be more likely to get a COVID-19 vaccine if it was offered to them at a place they normally go to health care, compared to 23% of White adults. Four in ten Hispanic adults in this group (39%, rising to 49% of foreign-born) would be more likely to get vaccinated if they only needed to get one dose compared to a quarter (25%) of White adults. Over half (54%) of employed Hispanic adults who are not yet ready to get the vaccine say they would be more likely to get it if their employer gave them paid time off to recover from side effects compared to 19% of employed White adults. In addition, four in ten (38%) employed Hispanic adults in this group say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if their employer arranged for a medical provider to administer the vaccine at their workplace, compared to 14% of their White counterparts.

Certain financial and travel-related incentives may also be particularly effective in increasing vaccine enthusiasm among Hispanic adults, especially those born outside the United States. Over four in ten (41%) of Hispanic adults (including 63% of those born outside the US) who are not yet ready to get the vaccine say they’d be more likely to get vaccinated if it was required for international travel compared to 17% of White adults. There are also differences in responses to employer incentives to get vaccinated. Nearly four in ten (38%) of employed Hispanic adults who are not yet ready to get the vaccine said they would be more likely to get it if their employer offered them a $200 incentive to get vaccinated, versus 22% of their White counterparts.

COVID-19 Vaccine Information Gaps and Needs

Increased outreach and education about how, where, and when to the vaccine may also facilitate increased vaccinations among the Hispanic population. Increasing awareness that the vaccine is free regardless of insurance status and available to all individuals regardless of immigration status may also encourage vaccination among those concerned about costs or potential negative immigration-related consequences.

Larger shares of Hispanic adults compared to White adults report lacking information about when and how to the get the vaccine, with particularly large information gaps among those who are foreign-born, who are Spanish-speakers, and who have lower incomes. Despite broadened eligibility for vaccines across states, 42% of unvaccinated Hispanic adults (compared to 26% of unvaccinated White adults) say they are unsure if they are eligible to receive the vaccine in their state, with this share rising to 57% among the potentially undocumented, 49% among Spanish speakers, and 47% with household incomes below $40,000. Similarly, 29% of Hispanic adults overall say they don’t have enough information about where to get a vaccine, including higher shares of potentially undocumented (43%) and Spanish-speaking (38%) Hispanic adults. Nearly half of all unvaccinated Hispanic adults (45%) say they lack information about when they can get a vaccine, and this share rises to more than half among those who are potentially undocumented (58%), those who completed the interview in Spanish (56%), and those with household incomes under $40,000 a year (54%).

Most Hispanic adults who completed the survey interview in Spanish (68%) say it is either “very easy” or “somewhat easy” to find COVID-19 vaccine information in Spanish, but 27% say it is at least “somewhat difficult.” Similarly, most Spanish speakers say they were able to access information or communicate in their preferred language when making their vaccine appointment (68%) and when getting their vaccine (77%), but some say they were not able to communicate in their preferred language when making an appointment (26%) or getting the vaccine (22%).

There are gaps in knowledge that the vaccine is available for free among unvaccinated Hispanic adults. Roughly half (46%) of unvaccinated Hispanic adults know that the vaccine is available for free even for those without health insurance while 9% believe this is not the case and four in ten (43%) are not sure. More than half (54%) of unvaccinated Hispanic women know that vaccines are available for free while four in ten (39%) of Hispanic men are also aware of this. Knowledge that the vaccine is available for free is higher among unvaccinated Hispanics who completed the survey in Spanish (60%) versus those who completed it in English (37%). Among Hispanic adults ages 18-64 who have not yet gotten vaccinated, similar shares of those with and without health insurance are aware that the vaccine is available regardless of health insurance status (47% and 44%, respectively).

There also are gaps in knowledge about the vaccine being available to all people regardless of immigration status among unvaccinated Hispanic adults. The federal government has clarified that all people are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine regardless of immigration status. Four in ten unvaccinated Hispanic adults (42%) are aware that all adults living in the U.S. are eligible to receive a vaccine regardless of their immigration status, larger than the share of unvaccinated Black adults (15%) and White adults (27%) who know this is true. Yet, 9% of Hispanic adults believe it is not the case that all adults are eligible to get the vaccine regardless of immigration status and nearly half (48%) are not sure. Among unvaccinated Hispanic adults, a larger share of those who completed the survey in Spanish know that the vaccine is available regardless of immigration status compared to those who completed the survey in English (55% vs. 33%). Hispanic adults who are potentially undocumented are somewhat more likely than those born in the U.S. to incorrectly say it is not true that U.S. residents are eligible to get the vaccine regardless of immigration status (14% vs. 5%), while those born in the U.S. are more likely to say they’re not sure (56% vs. 35%).

Implications

Together these findings suggest that addressing access barriers and providing information through outreach and education efforts will be key for closing ongoing racial disparities in COVID-19 vaccinations for Hispanic adults. They indicate that increasing access to paid time off to get and recover from any side effects from the vaccine and making vaccines easily accessible through trusted sites of care and workplaces may facilitate uptake of vaccinations among Hispanic adults. Moreover, they highlight continued needs for outreach and education efforts within the Hispanic community to communicate how and where to get the vaccine and to clarify that the vaccines are free regardless of insurance status, that they are available to all people regardless of immigration status, and that receiving a vaccine will not negatively affect an individual’s current or future immigration status. The findings also reinforce why prioritizing equity in COVID-19 vaccinations is key, given the disproportionate health and economic impacts of the pandemic for Hispanic families and other people of color.

Methods

This KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The survey was conducted April 15-29, 2021, among a nationally representative random digit dial telephone sample of 2,097 adults ages 18 and older (including interviews from 778 Hispanic adults and 507 non-Hispanic Black adults), living in the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). Phone numbers used for this study were randomly generated from cell phone and landline sampling frames, with an overlapping frame design, and disproportionate stratification aimed at reaching Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black respondents. Stratification was based on incidence of the race/ethnicity subgroups within each frame. Specifically, the cell phone frame was stratified as: (1) High Hispanic: Cell phone numbers associated with rate centers from counties where at least 35% of the population is Hispanic; (2) High Black: Cell phone numbers associated with remaining rate centers from counties where at least 35% of the population is non-Hispanic Black; (3) Else: numbers from all remaining rate centers. The landline frame was stratified as: (1) High Black: landline exchanges associated with Census block groups where at least 35% of the population is Black; (2) Else: all -remaining landline exchanges. The sample also included 163 respondents reached by calling back respondents that had previously completed an interview on the KFF Tracking poll at least nine months ago. Another 358 interviews were completed with respondents who had previously completed an interview on the SSRS Omnibus poll (and other RDD polls) and identified as Hispanic (n = 221; including 67 in Spanish and 40 who screened as potentially undocumented) or non-Hispanic Black (n=137). An oversample of potentially undocumented Hispanic (n=32) respondents was reached by dialing prepaid cell phone number in the High Hispanic stratum and screening for potential residency status. Computer-assisted telephone interviews conducted by landline (298) and cell phone (1,799, including 1,411 who had no landline telephone) were carried out in English and Spanish by SSRS of Glen Mills, PA. To efficiently obtain a sample of lower-income and non-White respondents, the sample also included an oversample of prepaid (pay-as-you-go) telephone numbers (25% of the cell phone sample consisted of prepaid numbers) Both the random digit dial landline and cell phone samples were provided by Marketing Systems Group (MSG). For the landline sample, respondents were selected by asking for the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the opposite gender. For the cell phone sample, interviews were conducted with the adult who answered the phone. KFF paid for all costs associated with the survey.

The combined landline and cell phone sample was weighted to balance the sample demographics to match estimates for the national population using data from the Census Bureau’s 2019 U.S. American Community Survey (ACS), on sex, age, education, race, Hispanic origin, and region, within race-groups, along with data from the 2010 Census on population density. The sample was also weighted to match current patterns of telephone use using data from the January- June 2020 National Health Interview Survey The weight takes into account the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection in the combined sample and also adjusts for the household size for the landline sample, and design modifications, namely, the oversampling of potentially undocumented respondents and of prepaid cell phone numbers, as well as the likelihood of non-response for the re-contacted sample. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF (an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation), the Ford Foundation, and the Molina Family Foundation. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total | 2,097 | ± 3 percentage points |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 778 | ± 4 percentage points |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 507 | ± 6 percentage points |

| White, non-Hispanic | 717 | ± 4 percentage points |

| Hispanic Interview Language | ||

| Spanish | 334 | ± 7 percentage points |

| English | 444 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Hispanic Income | ||

| Less than $40k | 426 | ± 6 percentage points |

| $40k+ | 984 | ± 5 percentage points |

| Hispanic Immigration Status | ||

| U.S born | 363 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Permanent resident | 207 | ± 9 percentage points |

| Potentially undocumented | 185 | ± 9 percentage points |

| Hispanic Insurance Status | ||

| Insured (ages 18-64) | 399 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Uninsured (ages 18-64) | 203 | ± 9 percentage points |

Endnotes

- The survey used questions to determine the likely immigration status of respondents by asking those who were born outside the U.S. whether they were a permanent resident (i.e. had a green card) when they came to the U.S. or if their status had been changed to permanent resident since arriving. In the current survey, 18 percent of Hispanic adults said they have not been granted permanent resident status, indicating that they are likely to be undocumented immigrants, although this group may also include a small number of temporary lawful residents. ↩︎