Family Planning and Contraceptive Provision Among Females Enrolled in Medicaid

Introduction

Family planning services, which include contraceptive services and supplies as well as a broader set of services related to sexual and reproductive health, are key preventive services for women. Most women (87%) use contraception at some point and on average, women report using 3.4 methods of contraception throughout their lifetime. For low-income women in particular, Medicaid plays a major role in financing family planning services. Recognizing the importance of contraception and family planning services, federal Medicaid law classifies family planning services and supplies as a “mandatory” benefit category that states must cover. Federal Medicaid law has other protections that promote access to family planning services that:

- Prohibit providers from charging copayments or any other form of patient cost sharing for family planning services

- Establish a 90% federal matching rate (FMAP) for the costs of services classified as family planning, a higher rate than for other services

- Entitle beneficiaries to obtain family planning services from any provider that participates in the Medicaid program, called free choice of provider, including for beneficiaries enrolled in managed care organizations (MCOs)

All states cover prescription contraceptives for women, but they may limit access through utilization controls. Additionally, about half of states offer a range of family planning benefits including contraceptive services and supplies to individuals who do not otherwise qualify for full Medicaid coverage. States can establish these family planning programs by receiving permission from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) through a Section 1115 waiver or by amending their Medicaid programs with a State Plan Amendment (SPA). Recognizing the importance of contraceptive services for women, CMS recently added two measures of contraceptive care to the core health care quality measures, known as the Adult and Child Core Sets. These measures assess provision of the most and moderately effective contraceptive methods (i.e., sterilization, intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, injectables (e.g., Depo-Provera), oral pills, patch, or ring) to female beneficiaries.

Despite the special status of family planning services under Medicaid, very little is known about the provision of these services to Medicaid beneficiaries. To better understand the level of use of these services and to explore the variation in utilization across states, we examine the provision of contraceptive services and supplies, as well as provision of family planning services more broadly to reproductive age women (ages 15 to 49) continuously covered by Medicaid in 2018. We present new national and state-level data by age as well as comparisons by region. This analysis is based on claims data from the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) and is based on data from 43 states and the District of Columbia. Seven states are excluded due to concerns about data quality.

Findings

Among females ages 15-49 continuously enrolled in Medicaid in 2018, we looked at family planning service provision and contraceptive service provision (Table 1). Contraceptive services for this analysis included drugs, devices, procedures, and counseling intended to prevent pregnancy. Family planning services were defined to include all contraceptive services as well as related services to prevent and screen for some sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV, as well as gynecological exams and Pap smears.

By looking at service provision among those who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid, we minimize the impact of coverage churning, which can limit access to care.

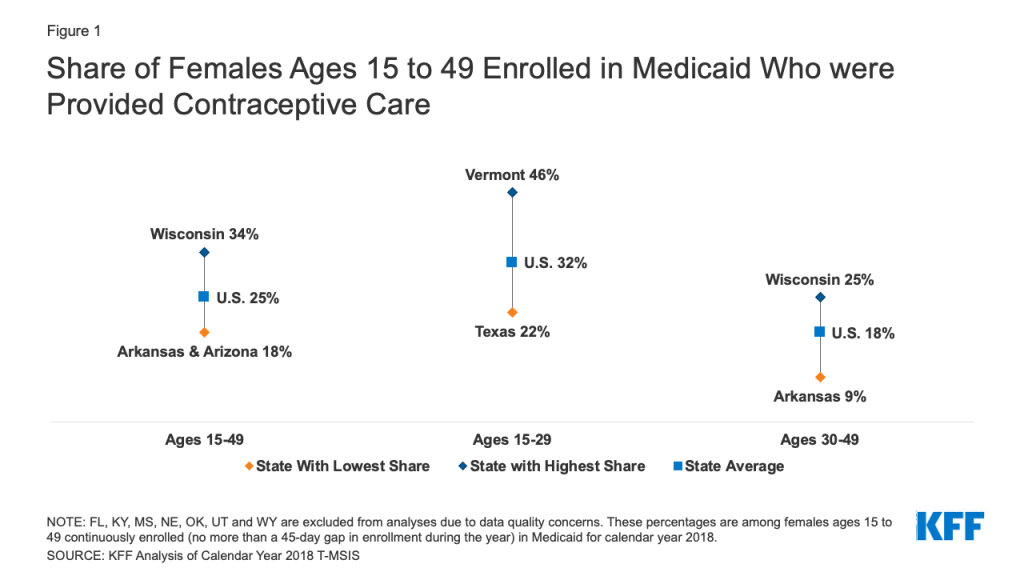

One in four (25%) female Medicaid enrollees of reproductive age (ages 15 to 49) obtained at least one contraceptive service in 2018.This share varied considerably, ranging from 18% in Arkansas and Arizona to 34% in Wisconsin (Figure 1). These percentages represent the share of females overall provided these services, which may include women who were pregnant during the year and not in need of contraceptive services.

Contraceptive provision was on average almost twice as high among females ages 15-29 (32%) than females ages 30-49 (18%). There was considerable variation in these rates by age across states with less than a quarter (22%) of females ages 15-29 in Texas receiving contraceptive services compared to nearly half of their counterparts in Vermont (46%). Among females ages 30-49, only 9% received contraceptive services in Arkansas compared to a quarter (25%) in Wisconsin.

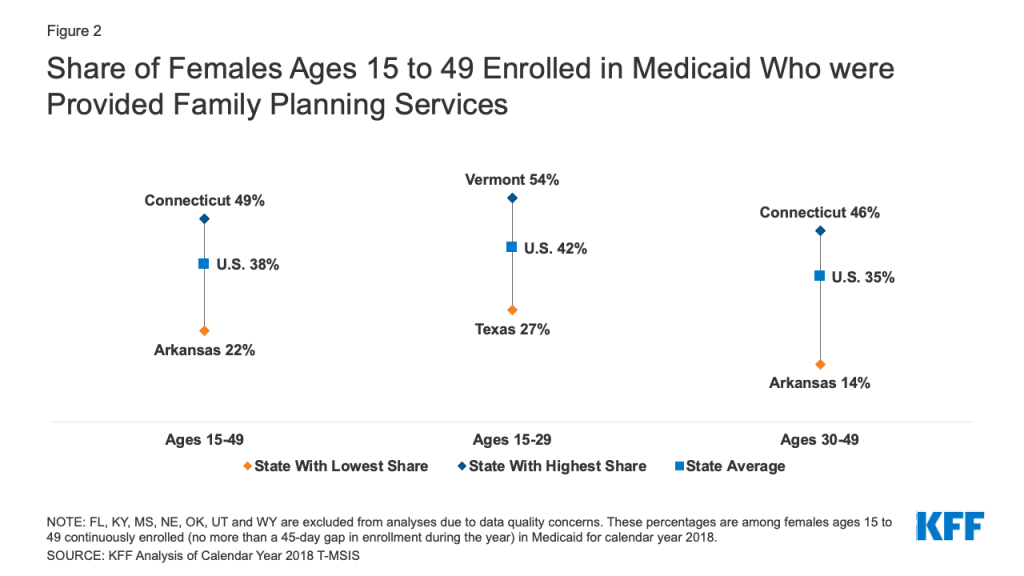

When looking more broadly at family planning services including screenings for sexually transmitted infections and cervical cancer in addition to contraceptive services, just under 4 in 10 females ages 15-49 (38%) were provided family planning services. This ranged from a low of 22% in Arkansas to a high of 49% in Connecticut (Figure 2). Younger females ages 15-29 were on average, 1.3 times more likely to receive family planning services compared to those ages 30-49 (42% vs. 35%). Among females ages 15-29, family planning service provision ranged from a low of 27% in Texas to a high of 54% in Vermont. The range was slightly wider among females ages 30-49 with 14% receiving family planning services in Arkansas compared to 46% in Connecticut.

Many factors can contribute to state level variation in provision of services, including eligibility levels, Medicaid utilization controls, access to clinicians, the availability of services, clinician practices, payment rates, beneficiaries’ needs and preferences, and more.

Nationally, the most commonly provided method of contraception to female Medicaid beneficiaries was oral contraceptives, which is also the most commonly used reversible contraceptive among females in the general population. Nearly half of women provided contraceptive services in Medicaid in 2018 obtained contraceptive pills (48%), followed by injectable contraception (20%), and then intrauterine devices (12%) (Figure 3). Approximately one in five (21%) females obtained a long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) in 2018, which includes IUDs and implants.

Among those continuously enrolled in Medicaid, only 4% of women had a diagnosis or procedure code for female sterilization in 2018. Since sterilization is a one-time procedure, women who were sterilized in earlier years would not show up in the current measurement year. Combined with IUDs and implants, one quarter of contraceptive users was provided a “most effective” method in 2018 (e.g., sterilization, contraceptive implants, intrauterine devices or systems (IUD/IUS)). Five percent of females was provided emergency contraceptive pills. Less than 5% of females were provided the other methods – patch, ring, diaphragm, or fertility awareness-based counseling.

For the following figures on contraceptive method provided, women could have more than one method within the year.

Contraceptive provision differs by age. Younger females in their teens and 20s had higher provision of oral contraceptives and lower use of sterilization than females in their 30s and 40s. Preferences regarding the type of contraceptive method often differs by a person’s age and the length of time they desire to prevent pregnancy. Not surprisingly, a larger share of females ages 30-49 received a sterilization procedure in the year, compared to females ages 15-29, who had higher use of reversible methods such as contraceptive implants, injectables, and oral contraceptive pills (Figure 4). Interestingly, about one in five females in each age group obtained a LARC (IUDs and implants) during the calendar year. The provision of contraceptive patches and rings was similarly low among both age groups. Less than 1% of females in each age group were provided a diaphragm. Similarly, a small share of females received fertility awareness-based counseling (1%) in each age group. Finally, 5% of females ages 15-29 and 4% of females ages 30-49 were provided a prescription for emergency contraception pills. Since emergency contraceptive pills can purchased over the counter without a prescription, some women may have used the pills but this would not be reflected in this claims database. For Medicaid to cover the costs of the pills, however, enrollees need to have a prescription.

There are some notable regional differences in the provision of contraceptive methods, particularly for oral contraceptives, injectables, and emergency contraceptive pills. We compared differences in types of contraceptives that were provided in the four census regions: West, South, Midwest, and Northeast (Figure 5), excluding FL, KY, MS, NE, OK, UT, WY due to concerns about data quality. The share of women provided sterilization in 2018 was highest in the South (5%), but similar across regions (4% in Midwest, 3% in West, and 3% in Northeast). The share of women provided an intrauterine device was lowest in the South (9% compared to 11% in Midwest, 12% in Northeast, and 13% in West) and the share receiving a contraceptive implant was lowest in the Northeast (7% compared to 9% in Midwest, 9% in South, and 11% in West). The largest differences were in the shares provided injectable contraception, with the highest share being in the South (27%) compared to 15% in the West. The share of women provided contraceptive pills was lowest in the South (42%) and highest in the Northeast (52%). The share of women provided emergency contraception was lower in the South (1%) compared to the West (7%), Midwest (5%), and Northeast (6%). There were not substantial regional differences in the shares of women provided the contraceptive patch, contraceptive ring, diaphragm, and fertility awareness-based counseling.

Discussion

Given the central role of Medicaid in financing family planning services for low-income women, it is important to understand what family planning service and contraceptive service provision looks like across states. While these are important services for many women, not all women need or want to use contraception. Our overall finding that 25% of reproductive age women were provided a contraceptive service is consistent with rates recently published by CMS, where 25.3% of women ages 21 to 44 at risk of unintended pregnancy were provided a “most effective” or “moderately effective” method of contraception. It is unclear whether the remaining women, who represent the majority of reproductive age women on Medicaid encounter access barriers or a lack of availability, or whether they feel they do not need or do not wish to use contraceptive services, or some other reason. Some of these women may be pregnant or trying to get pregnant and do not need contraception. Others may be using over-the-counter methods such as condoms or spermicide.

It is notable that there are considerable differences in provision of family planning and contraceptive services and supplies by age. A higher share of women in their teens and 20’s received contraceptive and family planning services compared to women over the age of the 30. This could partially be explained by higher shares of women over age 30 having had sterilization procedures in previous years as well as greater reliance on longer acting contraceptive methods, like IUDs which can last up to 10 years depending on the type of IUD. Regardless of age, contraceptive pills remain the most frequently provided contraceptive method within Medicaid overall, followed by injectable contraception (e.g., Depo-Provera).

Another notable finding is the substantial state variation in the share of women provided contraceptive and family planning services. Similar to our findings, an analysis of contraceptive utilization in 37 states using the 2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) among women with different insurance types found lower contraceptive use among women aged 18-49 in the South compared to the West. Some of the states that we found to have the highest and lowest shares of contraceptive use among women with Medicaid were also found to have higher and lower shares of contraceptive use in the BRFSS data, including higher shares in Wisconsin and lower shares in Arizona and Arkansas.

These differences by state could reflect the variation in the adoption of policies and programs to increase access to contraception, including those from public health practitioners, clinicians, and state and federal policymakers. Many initiatives to expand contraceptive access have focused on expanding access to postpartum LARCs. Notably, many states revised their payment policies to make it easier for providers to get reimbursed for immediate postpartum LARCs outside of the global maternity care fee. For example, Louisiana and South Carolina, states that implemented a separate payment structure for postpartum LARC insertions were found to have the highest rates of effective contraceptive provision 60 days postpartum among Medicaid enrollees in 2016. These states also had considerably higher contraceptive provision than their neighboring states in our analysis.

Furthermore, state adoption of utilization control policies can also shape access and availability of contraceptive methods. These policies include prior authorization for certain methods like emergency contraception, step therapy that require beneficiaries to use contraceptives off a Preferred Drug List before being able to use another method of choice and limiting the amount of supply a beneficiary can receive at one time, such as a 1-month or 3-month supply rather than the recommended 12-month supply.

Due to the personal nature of reproductive health care choices including contraceptive use and the history of reproductive coercion in many communities in the US, there is no agreed upon benchmark for contraceptive provision and method mix. However, information about the provision of services and how use varies by state and populations provides policymakers and clinicians important insights about the differences across states and sets a baseline for the study of future policy changes and initiatives.

Methods

This analysis is based on claims data from the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) Research Identifiable Files (RIF). Data for 2018 were from the final version (Release 1) of these files. This analysis was limited to females ages 15-49 continuously enrolled in Medicaid with no more than a 45-day gap in enrollment during the year. This definition of continuous enrollment was chosen to align with CMS’ Adult and Child Set Core Measures, specifically, those around contraceptive provision, and to give people sufficient time in Medicaid to access contraceptive and family planning services.

We excluded the following states from our analysis due to concerns with the quality of their enrollment data: Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Utah, and Wyoming. We relied on data quality assessments from DQ Atlas to exclude states based on data quality ratings of the following indicators: (1) Enrollment Benchmarking: Medium concern for Total Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment (Mississippi, Nebraska, and Kentucky), (2) Enrollment Patterns Over Time: Number of Enrollment Spans - % of Beneficiaries with Only One Enrollment Span in Year ≥ 99.8 (Florida, Wyoming), (3) Enrollment Patterns Over Time: Number of Enrollment Spans - % Beneficiaries with 3 or More Enrollment Spans in Year ≥ 5% (Oklahoma). Additionally, we excluded Utah because of a substantially lower rate of continuous enrollment, which may be due to an administrative error where a large number of enrollees were disenrolled from April 31, 2018 to June 1, 2018. The analysis was limited to 2018 claims, so enrollees that may have been enrolled in the previous or subsequent year but had more than one 45-day gap in enrollment in 2018 were truncated and excluded from the continuously enrolled population for the 2018 calendar year. Data reflect enrollment in any eligibility pathway as well as any payment structure (FFS, managed care, etc.)

Contraceptive claims were captured from the 2018 T-MSIS header and line files for “other services” claims and prescription drug claims, as well as the header files for inpatient claims for provision of female sterilization, intrauterine devices (IUDs), contraceptive implants, injectables, contraceptive pills, contraceptive patches, contraceptive rings, diaphragms, male and female condoms, emergency contraception, counseling for fertility-awareness based methods, contraceptive counseling, and contraceptive management and surveillance of other contraceptives. Family planning services included any contraceptive claims, as well as claims for sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening, gynecological exams and pap smears, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) counseling and screening, and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) screening. According to the DQATLAS, the following states had unusable data for one or more files: Rhode Island (inpatient claims volume), Tennessee (inpatient diagnosis codes), Maryland (inpatient procedure codes), and Utah (other services professional procedure codes). Since the other data, particularly for the “other services” files and RX files where the majority of family planning and contraceptive service claims are found, we did not exclude any states based on these ratings.

The share of beneficiaries provided contraceptive services included any female ages 15-49 continuously enrolled in Medicaid with at least one contraceptive service claim in 2018. The share provided family planning services included any female ages 15-49 continuously enrolled in Medicaid with at least one claim for contraceptive services, sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening, gynecological exams and pap smears, HIV counseling and screening, and HPV screening. A list of diagnosis, procedure, and drug codes that were used for this analysis are available upon request.