Detailed Findings

Introduction

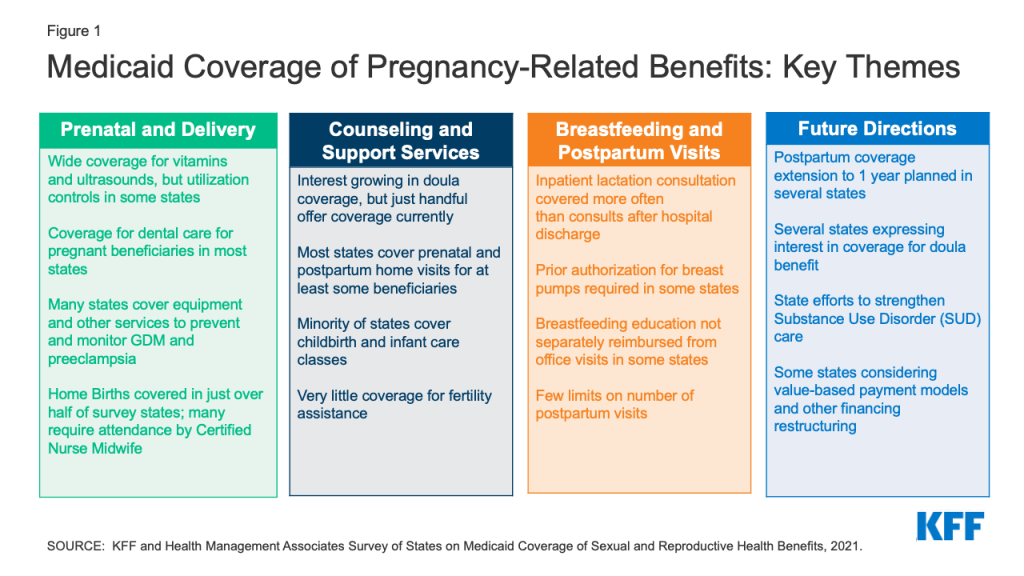

Medicaid covers more than four in ten births nationally and the majority of births in several states. This survey asked states about the specific maternity services they cover. The range of pregnancy-related services that states cover is shaped by many factors, and states have significant latitude to set income eligibility levels, define specific maternity care services, and apply utilization controls such as prior authorization and preferred drug lists (PDL).

While states can vary in the benefits they provide to some pregnant individuals depending on their eligibility status, the vast majority of states provide the full Medicaid package to all pregnant beneficiaries. A majority of states contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) under a capitated structure to deliver Medicaid services, and plans may vary in their coverage of specific services. This survey’s questions focused on state Medicaid policies and coverage under fee-for-service, and these policies typically form the basis of coverage for MCOs.

In addition to benefits, states also have discretion regarding reimbursement methodologies which also affect beneficiaries’ access to maternity care services. For example, maternity care is often reimbursed as a bundled payment that covers all professional services provided during the perinatal period, including prenatal care, labor and delivery, and postpartum care, and a separate facility fee. This kind of payment for an episode of care can help states manage costs and also provide incentives for coordination of comprehensive care across maternity providers. Bundled payments, however, also make it more difficult to track the delivery of component services that may be included in the bundle, such as health education or counseling.

This report presents detailed survey findings from 41 states and DC on fee-for-service coverage and utilization limits for Prenatal care and Delivery, Fertility Services, Counseling and Support Services, Substance Use Disorder Services, and Breastfeeding Supports and Postpartum Care.

Prenatal Care

Prenatal care services monitor the progress of a pregnancy and identify and address potential problems before they become serious for either the mother or baby. Increasing the share of pregnant women who begin care in the first trimester is one of the national objectives of the federal government’s Healthy People 2030 initiative. Routine prenatal care encompasses a variety of services, including provider counseling, assessment of fetal development, screening for genetic anomalies, prenatal vitamins that contain folic acid and other nutrients, and ultrasounds, which provide important information about the progress of the pregnancy. Access to routine prenatal care provides an opportunity to identify any problems with the pregnancy early on and is associated with lower rates of some pregnancy-related complications.

Prenatal Vitamins and Ultrasounds

All responding states reported covering prenatal vitamins and ultrasounds for pregnant people, but some states impose utilization controls. While states are not required to cover over-the-counter drugs, they must cover nonprescription prenatal vitamins. The majority of states reported that coverage for prenatal vitamins and ultrasounds aligned across coverage eligibility groups, with exception of Oklahoma (for prenatal vitamins) and Utah and Mississippi (for ultrasounds).

States reported using utilization controls to manage the benefit for prenatal vitamins such as days limits, generic requirements, and inclusion on a Preferred Drug List (PDL) (Table 1). Two states, Iowa and Pennsylvania, require prior authorization, although Pennsylvania noted that it was only required for non-preferred prenatal vitamins. Alaska and Wyoming reported they require prescriptions for Medicaid to cover prenatal vitamins. Washington reported that not all formulations of vitamins are covered. The state also noted that there may be coverage variation between MCOs.

Quantity limits and medical necessity requirements were the most common utilization controls states reported for ultrasounds. Most states reported that ultrasounds were limited to two or three per pregnancy, with additional allowed if medically necessary. Pennsylvania only covers one ultrasound per pregnancy, while Utah allows for 10 ultrasounds in a 12-month period. Oklahoma covers two ultrasounds per pregnancy but allows one additional to identify or confirm a suspected fetal or maternal anomaly. Two states, Indiana and West Virginia, only cover ultrasounds with “medical necessity.” Indiana does not cover routine ultrasounds or ultrasounds for sex determination, and West Virginia covers ultrasounds in accordance with criteria for high-risk pregnancies established by ACOG.

Childbirth and Parenting Classes

There are a variety of support services that can aid pregnant and postpartum individuals with pregnancy, delivery, and childrearing. These include childbirth education classes, infant and parenting education classes, and group prenatal care.

Less than half of responding states reported that they cover childbirth and parenting education for pregnant people. Fifteen states provide coverage for childbirth education classes through their Medicaid program, and 14 cover infant care/parenting education classes (Table 2). Eleven states cover both services—Arizona, Colorado, DC, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. States that cover these classes report aligning coverage across all eligibility coverage pathways available in the state.

Most states that cover these programs provide separate reimbursements to providers. Eleven states reimburse separately for childbirth education, and five reimburse as an office visit component, while seven reimburse separately for infant care/parenting classes. Colorado limits childbirth and parenting education to provision during routine prenatal visits. Wisconsin only provides childbirth and parenting education to women if they are enrolled in the state’s Prenatal Care Coordination program for those at higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Only twelve of the responding states reported covering group prenatal care for their Medicaid population. Group prenatal care typically involves a group of eight to ten pregnant people meeting with a health provider over ten visits for about 90 minutes to two hours to discuss questions and concerns. Research suggests that pregnant people who participate in group prenatal care have more knowledge about prenatal care, feel more prepared for labor and delivery, have lower rates of premature births and babies with higher birth weights, and are more likely to begin breastfeeding. Three states, California, Texas, and Utah, limit the number of visits or hours for group prenatal care. Texas limits group prenatal care to a maximum of 10 visits per 270 days and counts group visits toward the total combined limit of 20 prenatal visits per pregnancy. Utah maintains a limit of eight sessions in a 12-month period. California Medi-Cal will cover up to 27 hours. Colorado specified that group prenatal care is only covered for individuals enrolled in special programs for beneficiaries with higher risk pregnancies Maryland currently does not cover group prenatal care but reported the state is working towards it for 2022.

Dental Services for Pregnant Enrollees

Thirty-nine of the responding states cover dental services for pregnant Medicaid enrollees. Five of these states limit coverage to emergency dental services. There is some evidence that pregnant people are at higher risk for periodontal disease during pregnancy and that a mother’s dental health status is linked to her child’s future dental health status. While state Medicaid programs must cover dental services for children, including oral health screenings and diagnosis and treatment services, federal law does not require states to cover dental benefits for adults. States can choose to cover dental benefits and have considerable discretion in defining Medicaid adult dental benefits. In 2021, federal legislation was introduced that would require state Medicaid and CHIP programs (and some private plans) to cover dental health services for pregnant and postpartum individuals, but currently there is no national requirement.

Prior authorization, spending limits, and limiting coverage to emergency dental services were common utilization controls reported by states (Table 3). Arizona, Hawaii, Maine, Texas and West Virginia reported that they only cover emergency dental care. In addition, Hawaii also covers procedures needed to control or relieve pain, bleeding, elimination of infections, and management of trauma.

Low-Dose Aspirin

The majority of the responding states (36 out of 40) reported covering low-dose aspirin for pregnant people under their Medicaid Programs. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin as a preventive medication for pregnant people at risk for preeclampsia, a serious health condition characterized by high blood pressure and signs of damage to organ systems like kidneys and liver that occurs after the 20th week of pregnancy. Worldwide, preeclampsia is the second cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, and it affects one in five pregnancies beyond 20 weeks in the United States. During 2014–2017, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy accounted for 6.6% of maternal deaths in the United States.

Five states impose utilization controls on low-dose aspirin. Kansas and Louisiana have quantity limits, while Connecticut covers aspirin as a pharmacy benefit with a diagnosis of preeclampsia. Iowa requires prior authorization, and Wyoming requires a prescription for coverage. Alaska, Florida, Oklahoma, and Virginia do not cover low-dose aspirin under their programs (Table 4).

Blood Pressure Monitor & Scales

Most responding states (31 of 41) cover Blood Pressure (BP) monitors for home use as a pregnancy-related service, while few states cover scales to monitor weight. These tools can be helpful for monitoring the health of the pregnancy, particularly for people at risk for preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or other pregnancy-related conditions. Five states (Alaska, California, Missouri, Mississippi and North Carolina) noted coverage was subject to medical necessity, and two states have limited coverage to one blood pressure monitor every five years (Pennsylvania) or every three years (North Carolina). Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, and Mississippi require prior authorization for blood pressure monitor coverage, although Connecticut noted that it only requires prior authorization for wrist monitors, not upper arm monitors. New Jersey reported they require a prescription to cover monitors. All but two states, Utah and West Virginia, indicated that coverage policies were aligned across eligibility groups. While both blood pressure monitors and scales can be useful for pregnant people to monitor their health, only nine states—Arizona, California, Delaware, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oregon, Utah, and Vermont, cover weight scales for pregnant people.

Gestational Diabetes Services and Supplies

The majority of states cover continuous glucose monitors and nutritional counseling to support pregnant people with gestational diabetes. Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes that appears during pregnancy for the first time. In the United States,10% to 20% of all pregnancies are affected by gestational diabetes, which can increase a pregnant person’s risk of having high blood pressure during pregnancy and developing Type 2 Diabetes after pregnancy. Both the USPSTF and HRSA recommend that pregnant people get screened for gestational diabetes at around 24 weeks gestation.

Thirty-five of the responding states reported covering continuous glucose monitors (Table 5). Six states, Alaska, Connecticut, Florida, Kansas, Oregon, and Wisconsin do not cover them. Mississippi, North Carolina, Nevada, Oklahoma, Texas, and Washington require prior authorization to cover glucose monitors, and three states—California, Louisiana, and Montana—have medical necessity requirements. Louisiana covers monitors for adults with poorly controlled Type 1 Diabetes, while Montana will cover them for those with a gestational diabetes or diabetes mellitus diagnosis.

Thirty-four responding states cover nutritional counseling for pregnant people. Five of these states (Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, and Texas) reported that they covered nutritional counseling as part of a routine prenatal care visit with a medical provider, not as a separate visit with a nutritional counselor. Maine covers these visits only when they are provided by a physician, dietician, or family planning agencies. Alaska, North Carolina, Nevada, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Utah limit the number of visits or hours that they cover.

Delivery and Postpartum Care

Home Births

More than half of responding states (25 of 42) cover home births under Medicaid. While clinicians, maternal health researchers, and birthing parents have been discussing home births for decades, interest has grown since the start of the COVID pandemic. New Jersey reported coverage for home births, but only in two of its MCOs. One state (Texas) reported requiring a prior authorization request from a physician during the third trimester for a delivery by a Certified Nurse Midwife (CNM) indicating that the patient is not at high risk for complications and is suitable for a home delivery. Several states also commented on provider requirements, stating that home births must be attended by a physician or certified nurse midwife (CNM).

Postpartum Visits

The majority of responding states (35 of 41) reported no limits on the number of covered postpartum visits. Guidelines for postpartum care have evolved over time. ACOG and other professional organizations recommend that postpartum individuals have contact with their obstetric care providers within the first three weeks postpartum, with ongoing care as needed. This means that multiple visits may be needed for many people after delivery. However, in many states, pregnancy coverage ends 60 days postpartum. In states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion, many people can remain on Medicaid after that time as parents or qualify for subsidies to purchase private insurance in the Marketplace. In non-expansion states however, many postpartum people lose coverage after pregnancy Medicaid ends, falling into the coverage gap because their income is too high to qualify for Medicaid as a parent but too low to qualify for subsidies in the Marketplace, cutting off access to postpartum visits and other health care services just two months after childbirth. (Note: Disenrollment from Medicaid has been suspended during the Public Health Emergency).

Six states reported limits on postpartum visits (Table 6). Rhode Island reported a limit of five postpartum visits, while Alabama reported a limit of two visits, and four states (Kansas, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Vermont) reported a one-visit limit. Of the four states reporting a one-visit limit, Vermont indicated that the limit did not apply in the case of a twin delivery. Louisiana reported the state covers one visit defined as a postpartum visit but that there were no limitations on additional visits. While Texas and North Carolina reported no limits on the number of postpartum visits, Texas indicated having one postpartum procedure code that could be reimbursed once per pregnancy that covers all postpartum care regardless of the number of visits provided. Similarly, North Carolina reported that postpartum care is billed under a global postpartum package code, regardless of the number of visits provided.

Postpartum Depression Screening and Treatment

Almost all responding states reported that they cover postpartum depression screening and treatment. Rhode Island was the only state that reported that it doesn’t cover postpartum depression screening, and Virginia was the only state reporting no coverage of postpartum depression treatment. More than half of the states reporting coverage of postpartum screening indicated that screening services were reimbursed separately while the rest reported that screening was reimbursed as a component of an office visit. Maine indicated that screening can be reimbursed either way depending on the provider that is billing. Only a few states mentioned imposing utilization controls on depression screenings: California (two per year per pregnant or postpartum enrollee); Iowa (limit of two screenings); Kansas (three prenatal and 5 postpartum); and Pennsylvania (one per day). Three states (Oklahoma, Texas, and Washington) noted that postpartum depression screenings are covered as part of an infant or child Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) screening. Several states noted that utilization controls on postpartum depression treatment would depend on the behavioral health treatment service provided. For example, Mississippi noted that inpatient stays required prior authorization. Two states (Oklahoma, Pennsylvania) also noted prior authorization requirements for non-preferred medications or a generic requirement.

Doulas

Only three states—Indiana, New Jersey, and Oregon—reported covering doula services as of July 1, 2021. Minnesota, which did not respond to this survey, has also covered doula services through their state Medicaid program since 2014. A doula is a trained non-clinician who assists a pregnant person before, during and/or after childbirth, by providing physical assistance, labor coaching, emotional support, and postpartum care. Pregnant women who receive doula support have been found to have shorter labors and lower C-sections rates, fewer birth complications, are more likely to initiate breastfeeding, and their infants are less likely to have low birth weights. In recent years, there has been growing interest in expanding coverage of doula services through Medicaid, in part due to the high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States and the disproportionately high rates of poor maternal outcomes experienced by Black and Native American pregnant people. Federal legislation has been introduced to expand coverage of doula services through Medicaid, and some states are taking steps to include coverage through their state programs.

Medicaid policy requires states to cover certified medical professionals. Many doulas are trained by community-based organizations (CBOs), but most states do not recognize doula certification by CBOs. The three states that reported covering doulas have taken different approaches (Table 7). Indiana reported they cover doula services through community health workers and cover approximately 12 hours per month. New Jersey covers eight visits during the perinatal period, but if the pregnant person is under the age of 20, the state covers 12 visits. Oregon covers a minimum of two visits and has no maximum number of visits. Oregon includes doulas who have completed a training program in their state registry of certified health workers, while neither Indiana nor New Jersey has a doula registry. The states have also approached reimbursements differently. Oregon reimburses doulas directly, while Indiana provides reimbursements indirectly, through their billing or supervising provider. New Jersey allows for both direct and indirect billing. There is a wide range in how much state Medicaid programs are reimbursing doulas for their services. Oregon pays a flat fee of $350 per pregnancy, while Indiana reported that the state pays $2,095 per pregnancy.

Four additional states reported that they would begin covering doula services in 2022. Massachusetts plans to submit a State Plan Amendment (SPA); Virginia will begin coverage on April 1, 2022 (and will have a state registry); and Maryland is moving towards having doula coverage in 2022. Nevada began coverage on January 1, 2022 and reported additional details which can be found below in Table 7. Furthermore, several states reported that they are considering adding doula benefits under Medicaid, which is discussed later in this report in the section entitled, “New Initiatives.”

Fertility Services

Very few states cover fertility-related services under Medicaid. Fertility care encompasses a spectrum of services, including counseling, diagnostic, and treatments such as medications, egg freezing, intrauterine insemination (IUI), and in vitro fertilization (IVF). Eleven states reported that they cover fertility counseling outside of a well woman visit (Table 8). Eleven states cover diagnostic testing related to fertility, although some cover tests only for medical reasons other than for fertility. While federal rules require states to cover most prescription medications under Medicaid, there is an exception that allows states to exclude coverage for fertility medications. Just four states (California, Illinois, New York, and Wisconsin) reported coverage of fertility medications such as HMG for women under their Medicaid programs. Coverage is aligned across eligibility groups for the most part, except that California does not cover fertility services under their family planning SPA. Illinois is the only state that reported coverage for all fertility services asked in the survey under their Medicaid program, including IVF, IUI, and egg freezing.

Genetic Screening

Routine prenatal care typically includes ultrasound and blood marker analysis to determine the risk of certain congenital conditions such as down syndrome. While these tests are effective screening tools to determine risk, they are not diagnostic. If the results of screening tests are abnormal, genetic counseling is recommended and additional testing such as chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis may be needed.

Most responding states (38 of 40) cover 1st trimester genetic screening for pregnant women. Many of the states require prior authorization and specific medical conditions must be met such as high-risk pregnancy conditions and age-related risk (Table 9). Several states noted specific medical necessity requirements for the relatively new cell-free DNA tests. Nevada reported that they do not cover cell-free DNA tests.

All responding states reported covering amniocentesis, and most states (39 of 42) cover Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS). Some states provide coverage for these screening tests subject to medical necessity requirements. California limits CVS to individuals in the first and/or second trimester of pregnancy. New Jersey covers CVS for those 35 years or older. Alabama, Indiana, and Mississippi reported that they do not cover CVS.

Most responding states (32 of 42) cover genetic counseling. Most states reported that they cover genetic counseling during pregnancy, but some states, such as Alaska and Connecticut, report that they cover it as part of an office visit. This may be in part because genetic counselors are not recognized as a provider type in some states. Several states also report that they provide coverage subject to medical necessity requirements such as high-risk pregnancy. Washington limits coverage to one initial prenatal genetic counseling encounter and two follow-up encounters per pregnancy to occur not later than 11 months after conception.

Counseling and Support Services

There is a range of services outside of traditional obstetric care that can support low-income people during pregnancy. Case management is a Medicaid benefit that provides assistance with coordinating and obtaining external supports such as nutritional counseling and educational classes. Medicaid’s non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit facilitates access to care for low-income beneficiaries who otherwise may not have a means of getting to health care appointments. A broad range of transportation services, such as taxicabs, public transit buses and subways, and van programs, are eligible for federal Medicaid matching funds.

Most responding states provide case management services to at least some pregnant beneficiaries. Several states noted that case management services were limited to high-risk pregnancies, qualifying conditions, targeted populations, and/or first-time mothers, and a few states reported specific service limits, such as a certain number of units or hours per month (Table 10). Two states (California and Utah) reported that service limits were determined by “medical necessity,” and one state (Connecticut) noted that case management was covered as part of overall prenatal reimbursement and not reimbursed separately. Four states—Arizona, Louisiana, Michigan, and Nevada—reported that they did not provide case management services to pregnant women. Of the 36 states covering case management services for pregnant women, the vast majority (34) indicated that coverage policies were aligned across eligibility groups. Two states reporting coverage only in the case of high-risk pregnancies (Alaska and Mississippi) indicated that their coverage policies were not aligned.

All responding states reported covering NEMT services for pregnant beneficiaries, as is federally required. Only four states (Alaska, Iowa, Mississippi, and Utah) reported that NEMT coverage policies were not aligned across eligibility groups including Mississippi, which provides an NEMT benefit only to beneficiaries with full Medicaid benefits, and Iowa, which does not cover NEMT services for ACA expansion adults. A few states noted that NEMT services were subject to prior authorization, limited to 300 miles per day (Pennsylvania), limited to medical providers within 125 miles (West Virginia), or must be requested by a provider (Massachusetts).

Most responding states cover both prenatal and postpartum home visits. Home visits are typically visits by nurses or other clinicians to pregnant and postpartum people to provide support with medical, social, and childrearing needs. There are a number of different models of home visiting programs, and some are associated with improvements in birth outcomes and early childhood measures. There are multiple streams of financing for home visiting programs in states, including through Medicaid, the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program, and state public health departments.

Several of the responding states noted that home visiting benefits were limited to high-risk beneficiaries, subject to prior authorization, or as part of a Nurse Family Partnership program for first-time mothers Oklahoma, South Carolina. In contrast, Indiana reported that both prenatal and postpartum home visits were provided through community health workers, and Michigan reported that, in addition to medically necessary prenatal and postpartum home visits, every pregnant and infant beneficiary is eligible for the Maternal Infant Health Program (MIHP) – an evidence-based preventive home visiting program. New York allows all Medicaid beneficiaries who have given birth at least one postpartum home visit.

Five states (Florida, Montana, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wyoming) reported that they did not cover prenatal or postpartum home visits, although Tennessee indicated that while not required, MCOs provided varying levels of coverage, and Wyoming reported that the Department of Public Health covers postpartum visits.

Substance Use Disorders (SUD)

There is growing attention to the impact of substance use on pregnant and postpartum people as well as their infants. The federal Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act requires that states provide certain services for pregnant and postpartum people, including Medication Assistance Treatment (MAT), which includes medications such as buprenorphine and naloxone. In addition to MAT, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) recommends a variety of other services to support the treatment and recovery of people with substance use disorder, but states are not required to cover these under Medicaid. The SUPPORT Act also established a new state plan option to make Medicaid-covered inpatient or outpatient services available to infants with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) at a residential pediatric recovery center (RPRC).

Most responding states offer some SUD benefits to pregnant people beyond what is required by the SUPPORT Act. Of the 42 responding states, 36 reported offering expanded SUD benefits beyond the required benefit of MAT mandated by the federal SUPPORT Act. Of these 36 states, 27 reported offering all or most of the ASAM-defined levels of care,21 including residential care (Table 11). Five states reported covering outpatient SUD services, but not residential services, and two states did not specify the expanded services covered. As of July 1, 2021, ten states reported covering residential pediatric services for infants with NAS.

All but two of the responding states (Iowa and Maine) reported that coverage policies for SUD services for pregnant women were aligned across all Medicaid eligibility pathways: Iowa indicated that ACA expansion adults may receive SUD services only through the state’s MCO model if the member is determined to be “medically frail,” and Maine reported that its Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) program was specific to individuals who are pregnant or postpartum.

Breastfeeding Supports

A range of supports can help parents initiate and maintain breastfeeding, including breast pumps, lactation counseling by certified consultants, and educational programs, which can begin during pregnancy and continue after the birth of a child. States are required to cover breast pumps and consultation services for Medicaid expansion beneficiaries under the ACA’s preventive services requirement. For non-expansion states, there is no federal requirement for coverage of breastfeeding services.

Some states include coverage for breastfeeding education and lactation consultation as part of global maternity care payments and do not reimburse for them as separate services. Several states indicated that breastfeeding education is covered as part of an office visit or global maternity fee, rather than reimbursing separately, for example, for an instructor-led class. Nevada reported the service may be reimbursed either separately or as part of a physician office visit or daily hospital per diem rate. Three states reported limits to breastfeeding education: Wisconsin indicated that individuals must be enrolled in the state’s Prenatal Care Coordination program to receive covered breastfeeding education; North Carolina covers breastfeeding education only as a part of childbirth education classes; and Utah limits breastfeeding education to eight 1-hour units during a 12-month period. Indiana notes that breastfeeding education is provided through community health workers.

Lactation consultation services are more commonly covered in the hospital setting, compared to outpatient and home visits. Lactation support can be provided in multiple settings in the postpartum period, including in the hospital before discharge, at outpatient visits, or at home. States most frequently reported covering services in the hospital (Table 12). States also differ in whether the service is included as part of the global maternity feel or paid separately. Among states that cover hospital-based individual lactation consultants, 23 cover them as part of a DRG/global fee component, and four reimburse them separately. Slightly more than half of states (13) that cover outpatient/clinic based individual lactation consultants separately reimburse them compared to the 11 that include them as an office visit component. Home visits can be particularly helpful for new parents trying to breastfeed, care for a newborn, and recover from childbirth. Among states that cover lactation consultants as part of a home visit, roughly half (9 of 19) separately reimburse the service instead of including it as part of a home visit component. Washington only covers hospital-based lactation consultants, noting that many Medicaid beneficiaries receive lactation support from WIC clinics, which are funded separately from Medicaid, and Wyoming noted that although Medicaid does not cover them, home visits are covered under the state’s public health department. New Jersey reported that in FY2022, the state will allow lactation professionals to enroll as new providers, expanding lactation support services.

Several states use utilization controls such as quantity limits to manage these services: Michigan (two clinic- or home-based lactation visits per pregnancy), Oklahoma (six clinic- or home-based sessions per pregnancy), and North Carolina (six 15-minute clinic-based units a day with a lifetime maximum of 36 units if the infant has a chronic, episodic, or acute condition). Eight states reported that they do not cover any breastfeeding education and lactation consultation services (Arizona, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Texas).

A majority of responding states cover both electric and manual breast pumps, but some report using various utilization controls such as prior authorization or quantity limits. All but five of the responding states cover electric breast pumps, and 32 of 42 responding states cover manual pumps. Of the states that do not cover breast pumps in the Medicaid program, three—Nevada, Oklahoma, and South Carolina—report that pumps are provided through the state’s Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program.

Eight states impose quantity limits on the coverage of pumps, ranging from one every six months to one per lifetime. Several states require prior authorization for coverage of at least one type of breast pump: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, Texas, and Washington. Colorado only covers pumps for premature infants and those in critical care if the infant is anticipated to be hospitalized for more than 54 days.

Of the responding states, 15 reported that they offer all of the breastfeeding supports that the survey asked about: breastfeeding education, lactation consultations in the hospital, outpatient, and home settings, and electric and manual breast pumps (Figure 2).

New Initiatives

More than half of states reported that they are planning to implement at least one Medicaid initiative to address birth outcomes and/or maternal health in FY2022. Given the Medicaid program's large role in maternity care, states have many opportunities to strengthen the health of pregnant and postpartum people as well as newborns.

The most commonly reported new initiatives that states reported were related to extending pregnancy eligibility through 12 months postpartum (Table 14) as allowed by an option in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). Federal policy requires that pregnancy-related eligibility last through 60 days postpartum, but states have options to extend coverage beyond that time period. Medicaid eligibility levels for pregnant individuals are higher than eligibility levels for parents in most states, so women may lose Medicaid coverage at the end of the 60-day postpartum period, particularly in states that have not implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, where eligibility for parents remains very low. A provision in ARPA, that went into effect on April 1, 2022, allows states to now extend pregnancy coverage through 12 months postpartum by filing a state plan amendment (SPA). There has been a extensive activity at the state level since this survey was fielded, and the most up to date information is available in the online KFF Tracker on Medicaid Postpartum Coverage (Note: Currently postpartum people covered by Medicaid can remain on the program beyond 60 days because of a continuous enrollment requirement enacted in 2020 that lasts through the COVID public health emergency.)

To date, more than half of states have taken steps toward lengthening the postpartum coverage period beyond 60 days. This includes several states that have not yet opted to expand full Medicaid to all adults under the ACA, where the likelihood of losing coverage two months after delivery is higher than in expansion states. However, not all of these extensions meet the criteria for the ARPA option. For example, Missouri is extending postpartum coverage only for those with substance use disorders, whereas the ARPA option requires extension for all postpartum beneficiaries. Conversely, some states are proposing more expansive coverage extensions. Massachusetts, California, and Illinois are all proposing postpartum coverage extension for individuals regardless of immigration status, and Washington state has enacted legislation that would extend postpartum coverage, including for individuals who may not be federally qualified and for those who were not on the state’s Medicaid program during pregnancy. In addition to coverage extension, some states reported other efforts to strengthen postpartum care such as raising rates of postpartum visits among Medicaid beneficiaries, but they did not provide details about how they would do this.

Eleven states reported that they are considering adding doula services as a covered benefit. Most of these initiatives are in early stages, with some states piloting the benefit in selected counties and some states still in the planning stage. However, some states are further along with providing this benefit. This survey asked states to report benefits implemented as of July 1, 2021. In addition to the three states that already cover doula services, Maryland, Nevada and Virginia reported that their doula benefits would begin in 2022.

Eight states explicitly mentioned initiatives to address substance use or mental health services for pregnant or postpartum beneficiaries. For example, Colorado and Maine reported plans to implement a Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) model to integrate substance use treatment and obstetric services for pregnant and parenting individuals. In addition, six states reported that they are in the process of implementing or expanding home visiting benefits, which may be designed for higher risk pregnancies.

Other types of new initiatives reported by more than one state include: adoption and implementation of Medicaid MCO or provider performance measures/incentives to improve maternal health outcomes value-based purchasing arrangements or bundled maternity payments; community health workers (California and Nevada), and telehealth services for prenatal and postpartum care (North Carolina); multi-agency collaboration to address maternal health outcomes and disparities (Arizona, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas); and addressing social determinants of health (New York, Oklahoma). At least two states (Arizona, Montana) have efforts under way to provide supports for maternal mental health. A couple of states have planned initiatives to expand contraceptive access, either allowing over-the-counter access to (Illinois) and authorizing pharmacists to dispense self-administered hormonal contraceptives without a prescription (Nevada). This is discussed in more depth in a related report. Virginia reported that the state has launched the FAMIS Prenatal Coverage for uninsured pregnant individuals who don’t qualify for other full-benefit coverage groups because of their immigration status. Applicants do not need to provide immigration documents or a Social Security number to enroll in this new coverage, but do need to meet other eligibility criteria, including income level.