Unwinding the Continuous Enrollment Provision: Perspectives from Current Medicaid Enrollees

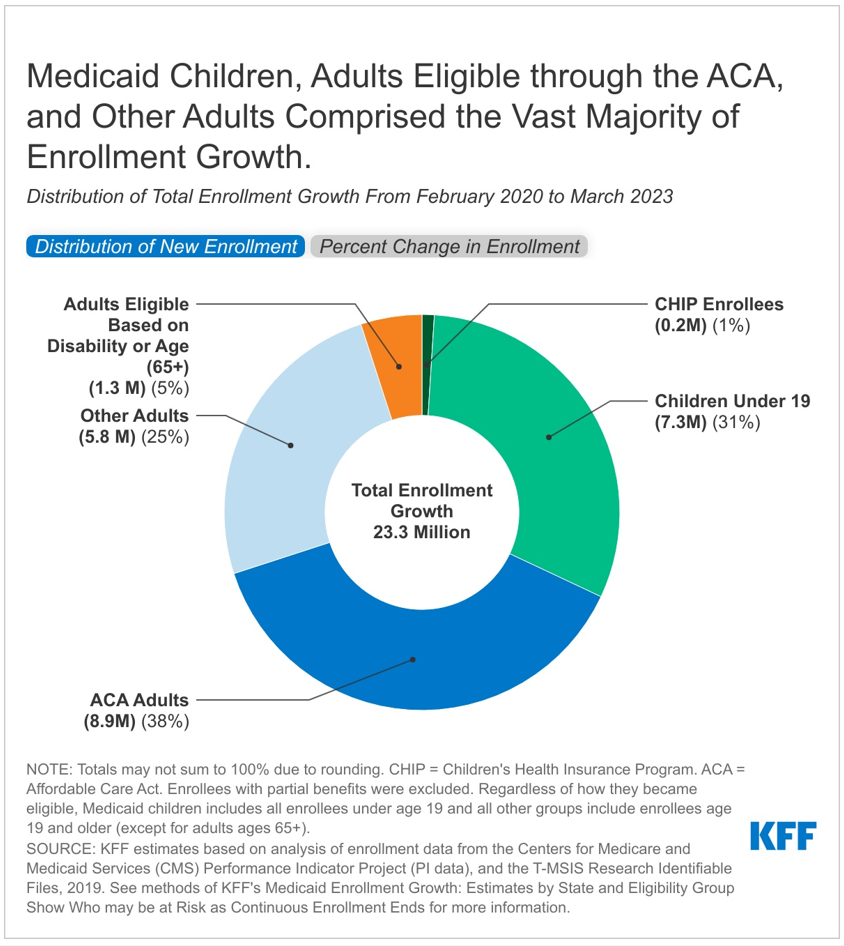

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, states have kept people continuously enrolled in Medicaid in exchange for enhanced federal funding. Largely due to these changes, KFF estimates that Medicaid enrollment will increase to 95 million, an increase of over 30% from enrollment in February 2020. The Medicaid continuous enrollment provision will end on March 31, 2023, and states will then begin disenrolling people who are no longer eligible or who are unable to complete the renewal process even if they remain eligible. We have estimated that Medicaid enrollment could drop by 5 to 14 million people over the coming year as states unwind continuous enrollment. As states prepare for the end of the continuous enrollment provision, a survey from December 2022 found that 62 percent of adults in Medicaid-enrolled families were not aware of upcoming renewals.

To help inform the implementation of the unwinding of the continuous enrollment provision, we conducted 5 virtual focus groups in late January and early February, shortly after federal legislation set an end date for the continuous enrollment provision. Groups included 39 adults who self-identified as having Medicaid coverage for themselves or had children enrolled in Medicaid across 12 states to learn about their experiences with Medicaid, awareness of the end of the continuous enrollment provision, experiences applying for and renewing coverage, and accessing care. We also explored the challenges they might face if they were to lose Medicaid coverage. Participants included a mix of adults by gender, race/ethnicity, age, length of time enrolled on Medicaid, and work and family status. Two groups were conducted in Spanish. KFF worked with PerryUndem Research/Communication to conduct the focus groups. Individuals who were able to participate in our groups needed to know that they were enrolled in Medicaid coverage, have two hours of time, a quiet space, a computer, and internet. These characteristics alone may not fully represent many Medicaid enrollees, so findings may not be generalizable to the entire Medicaid population. See Appendix Table 1 for demographic details about the participants. Key findings from our groups include the following:

- Many participants experienced worsening health and financial stability during the pandemic, but Medicaid was important in helping them access needed health care that was affordable.

- Awareness that Medicaid coverage had been protected during the pandemic was limited and most were not aware that disenrollments could start in April.

- All said that they would try to renew Medicaid coverage and participants said they want to hear about what to expect through multiple communication modalities and from different sources to ensure they would not miss an opportunity to renew coverage.

- Many participants were worried about losing Medicaid coverage because it would have negative implications for their health and finances. While some worried that they may no longer be eligible due to a change in income, many individuals worried about losing coverage even if their economic circumstance did not change. Under normal operations, people who are no longer eligible are disenrolled from Medicaid; however, a large number of people could be disenrolled in the coming year because of the continuous enrollment provision that has been in effect. Most said they would look for other coverage if they were no longer eligible for Medicaid, but expressed concerns that other coverage would not be affordable.

Key Themes

Experience with Medicaid and the Pandemic

Participants said Medicaid enables them to access health care services and medications for themselves and their children. Those with serious chronic health conditions and other health and mental health needs said having Medicaid means they can get medications and regular doctor’s visits to manage their conditions. In some cases, they say Medicaid coverage has meant access to life-saving treatments, surgeries and therapy services. While some participants noted problems accessing certain services, including dental care, most said Medicaid covers the services they need. Parents in the groups especially valued being able to access preventive and primary care, treatment for more serious conditions, and mental and behavioral health services for their children. A common theme expressed by participants was the peace of mind from knowing that they can get the care they need without having to worry about how they will pay for it. Several participants described getting Medicaid when they became pregnant and the importance of the coverage during their pregnancies and once their children were born.

Because I have a chronic disease, which is diabetes, and I have to go [to the doctor] every six months. Sometimes, with regular insurance, you have to pay a copay, and now, Medicaid pays for it. I take advantage of that. – 56-year-old, Hispanic male (Spanish-speaking), Arizona

I mean [Medi-Cal] does cover a lot, you know. I have to take a lot of medication now so, all my medications are covered, all my doctor visits. Before when I was uninsured, I didn’t even bother going to the doctor. So, once I went, I found out all these things that were wrong with me. So, it definitely helped. – 32-year-old, Asian male, California

It’s for my kids, obviously, but my son has asthma. It’s really important to me that he has insurance. He’s had two asthma attacks, where I’ve had to take him to urgent care, or to the emergency room at the hospital. I didn’t have to worry about how I was going to pay for that visit or all the services that they were going to provide. – 50-year-old, Hispanic female, Tennessee

In recent years, many participants had ongoing health and financial challenges, some of which were exacerbated during the pandemic. The pandemic was hard for many participants. Several lost jobs early in the pandemic and while some managed to find other full-time work, others were cobbling together part-time gig work or still not working. Many got sick with COVID-19; some said they had lingering side effects and one person reported developing long-COVID. Recent inflation pressures were adding to financial concerns for some participants. Several said buying food and paying for normal expenses has gotten harder and some were forced to move because they could no longer afford their rent. These health and financial challenges made affordable coverage through Medicaid even more valued than prior to the pandemic for a number of enrollees.

I’m customer service, I work with the general public and a lot of people in San Diego do take public transportation, so I have to be out there and on top of that, I ended up getting COVID. So that kind of screwed everything. I have COVID long haul now, so now my hours are all depending on how my body feels…sometimes I get 40 hours, sometimes I get 15, 20 hours. I don’t have set hours anymore because now with COVID it just, my income goes up and down. – 51-year-old, Hispanic male, California

Gig work just means that it’s penny to penny, paycheck to paycheck if you will. And like somebody mentioned earlier, you know, one week you’ve got 40 hours of work, the next week you have 20… can’t plan well. And so having the security of the Medicaid is everything. – 39-year-old, White female, Oregon

I don’t know, I have gotten into therapy over the last year and a half or so and I don’t know that I would be doing as well overall if I hadn’t and I wouldn’t be able to afford therapy or all the handful of medications I take every morning, if not for this [Medicaid]…- 42-year-old, White male, Michigan

Knowledge of the Continuous Enrollment Provision

Among focus group participants, awareness that Medicaid coverage had been protected during the pandemic was limited. Some states seem to have done a better job of communicating that coverage was being continued because of the pandemic, including Arizona, California, Colorado, and Texas, where some participants reported receiving notices saying their coverage had been renewed because of the pandemic. At the same time, other participants in these states and in other states claimed not to know about the provision, and most were unaware disenrollments would resume soon.

[I learned I had been automatically renewed] by a letter that I received. It was around November, saying that they renewed me again without me doing anything because of COVID, based on what they said in the letter. – 56-year-old, Hispanic male (Spanish-speaking), Arizona

It was in my portal, and they also sent me a letter in the mail to let me know that my kids had another year of Medicaid due to COVID-19. – 35-year-old, Hispanic female (Spanish-speaking), Texas

I was not informed of that by the State of Michigan. Seems like they, seems like it would, that should be something that could come out in one of the many letters they send. – 42-year-old, White male, Michigan

I think it’s [continuous enrollment] a good thing just because the cost of insurance. I mean if you have regular insurance nowadays you have the deductibles, you have, there’s still a lot of out-of-pocket costs and everything costs so much now that pharmaceuticals are going sky high. – 63-year-old, Black female, Arizona

Although most participants did not know that disenrollments in their states could begin as early as April 1, 2023, all said they would seek to renew their coverage although some were worried that they are at risk of losing coverage, especially as inflation concerns and health issues persist. All participants wanted to keep their coverage and planned to take steps to renew. While most participants had not heard that their states would be resuming disenrollments soon, some reported receiving a notice with this information or seeing it in their online account. Several participants who had changed jobs, gotten promotions, or increased their hours were worried they might lose coverage. Some were worried about losing coverage even if nothing changed in their economic circumstances. Many said they would seek help in trying to retain coverage if needed, from local assistance organizations, the local Medicaid/social service office, or from friends and family.

It’s kind of caught me off guard a little bit. I haven’t received any notice about [the end of continuous enrollment] so, uh, at least now I know like, I need to get my documents together. I haven’t heard about it and I haven’t received any notification from Medicaid at all. – 36-year-old, White female, Ohio

Every time I go to my account with my information, everything is written there. Before you log in, the whole message is there. How after March 31st, you’ll need to reapply or renew your benefits – 31-year-old, Hispanic female, Texas

The only reason I’ve been able to stay on Medicaid is because of this [continuous enrollment provision]. And I think I make like a thousand dollars over the limit for being qualified, but like I said, I’m paycheck-to-paycheck regardless, so I’m actually really concerned about not qualifying once this happens. – 32-year-old, White female, Oregon

I mean honestly my concern is just not totally understanding exactly what will disqualify me, so it would be nice to know more about that…nothing has really changed, but I still don’t trust it. – 39-year-old, White female, Oregon

Communicating with Medicaid

Most participants said they choose to receive communication from the Medicaid agency in multiple ways, including mail, email, text, and through their online accounts, so they do not miss important information about their coverage. Regardless of the preferred method for receiving information, most participants expressed concern about not wanting to miss information from Medicaid. Some participants said they prefer email, but others said their inbox was so full they worried important information would get lost. Participants in some states said they receive text messages and reminders; however, rules about text messaging vary by state. Similarly, participants in some states said they could receive notices through their online accounts but not everyone said they had that option. Even if participants preferred receiving notices and information through their online accounts, they also wanted to receive renewal reminders through other modes in case they forgot to check their accounts.

I have all of that [email, text, mail communications] because you just have to be aware now because…they don’t care if you didn’t get it. If you missed it, that’s it, you’re done you got to redo it all over again. – 34-year-old, Hispanic female, Arizona

For me, [communication] by email [is best]. But at the same time, it makes me wonder if maybe I might not get some mail that’s important…You get it once or twice a year, but it’s crucial information, and I wouldn’t want to not get that information. – 45-year-old, Hispanic male (Spanish-speaking), California

While many participants said Medicaid notices are clear and understandable, others found communications confusing, and some said they do not read the whole document. Most participants said they always read the Medicaid notices because they generally contain important information about their coverage. However, some participants admitted that sometimes they do not read all of the notices, in some cases because they felt the information was duplicative and unnecessary. Most participants said the notices clearly described any actions they needed to take and provided deadlines for renewing coverage or scheduling appointments. Some participants said they felt like they got conflicting information through their notices and providers or caseworkers and had to call the agency to help sort things out. Spanish speaking participants said they were able to get notices in Spanish, though some said they preferred to get the notices in English because some of the terminology used in the Spanish translations was unfamiliar to them.

Yeah, the [Medicaid notices are] clear. When you apply, they give you the information in whatever language you want to receive them in, so for me, they’re clear. – 39-year-old, Hispanic female (Spanish-speaking), Colorado

I have received some [notices] in the mail and the envelopes is bigger than a normal envelope and in black and bold letters it says your Texas Benefits. So, I normally open those right away. And I’ve never had any issues understanding what directions, you know, they’re trying to give me, or if I need to do anything. Because usually if I have to send something back, they’ll send me an e-mail with the link. – 50-year-old, Hispanic female, Texas

Sometimes you get the notices you’re told on the phone, for example, you’re approved everything’s done, you don’t need anything, we’ve got everything we need. Then you get a notice in the mail that oh, I need all of these things that they just told you didn’t need. So now you’re confused…it is like kind of in circles…And then you call, you’ve got to wait a billion hours on the phone to get somebody through, then they don’t know what you’re talking about. – 34-year-old, Hispanic female, Arizona

As far as Spanish, I think they use a term very rigidly, not how someone would normally speak it or understand it. That’s why people who understand it easily in English maybe won’t understand it [in Spanish]. – 35-year-old, Hispanic male (Spanish-speaking), Missouri

Participants had mixed experiences with calling the Medicaid agency. Participants may call the Medicaid agency to discuss issues with current coverage or about renewals. Some participants reported very long wait times calling Medicaid while others said they were only on hold for just a few minutes, and a participant in Arizona said wait times had gotten better recently. Those who faced long wait times described the calls as stressful. Prior to the pandemic, when calls were related to renewal of coverage participants said they were nearly always able to get this issue resolved, although sometimes the calls took several hours. However, participants seemed to have less success getting questions about participating providers or how to access certain services answered.

So, I was on hold with the Ohio Medicaid office for four hours trying to get verified for mine and my husband’s Medicaid. Yeah it took me four hours to get through to talk to someone. – 36-year-old, White female, Ohio

Despite broad-based efforts in many states to conduct outreach, most participants said they had not been asked by their Medicaid agency to update their contact information to prepare for the unwinding of the continuous enrollment provision. While some participants said they had recently updated their contact information after moving, only a handful said they had received a message from their state asking them to do so. Among those who had updated their information recently, they described the process as straightforward. Some updated their information through their online account, while others called the Medicaid agency to provide the information. They also noted the importance of updating their contact information with their managed care organization (MCO) or primary care physician, which they did as a separate step.

In the letters that they send me, reminder letters, they always remind me when I make a change. The same when you call on the phone, they ask if you’ve changed your address, phone number, or email. Because those are the three ways that they contact you. If there’s any changes, you can do it over the phone, and they’ll change it for you right away. – 50-year-old, Hispanic female (Spanish-speaking), Tennessee

It was fairly easy [to update contact information]. I just went through the app and did it and then I had to go through all of the PCP… or I had to go through PCP and everybody else and updated it. It took a minute, but I got it done. – 35-year-old, Hispanic female, Michigan

When it comes to communications about the unwinding of the continuous enrollment provision, participants said they want to hear about what to expect through multiple communication modalities and from different sources. Given the significance of the potential impending changes to their coverage, participants wanted states to communicate directly about the changes in many ways, using mail, email, text, and though their online accounts—the same ways in which participants receive regular notices. Because these changes are so significant, several also said they would like a personal phone call telling them what to expect. When asked specifically about using text messages, some people said they thought it was a good way to communicate, while others worried about fraud and that some people might ignore the message. Participants stressed the importance of making sure people understand the urgency of the information. They wanted the information to clearly indicate what actions people need to take and when and they wanted it early enough that they would have time to take the necessary steps to renew their coverage. Beyond communications from the Medicaid agency, participants also wanted to hear information from their doctors, from the media, and through social media. Some mentioned advertising on billboards, buses, and other places where people would likely see the information.

I think that besides mail, e-mail also, but bold, the March 31st should be in bold, I mean it should be, something that really stands out to let you know, this isn’t just the standard mail that you get, this is really serious or important to pay attention to it. – 63-year-old, Black female, Arizona

A text message, if it’s something more informative in general for all people, I think a text message would be the easiest, and in a way that most or almost all people would learn about it. – 39-year-old, Hispanic female (Spanish-speaking), Colorado

I don’t think text message because it’s a really public thing. As opposed to email, which is something a little more private. The same thing with social media. I think that’s a bad idea. – 20-year-old, Hispanic female, (Spanish-speaking), New Jersey

I would say get it to the doctors, the PCPs themselves and have a general service message from them saying, hey, if you have any customers that are under these government funded programs… to go ahead and tell them specifically. – 39-year-old, White male, Arizona

Applying for and Renewing Medicaid

Many participants had applied for Medicaid online and described the process as easy. For most participants, the online application was easy to complete and did not take a long time. But some, particularly those who were applying based on disability, had to provide what they described as a lot of paperwork and experienced delays in having coverage approved. Many states have integrated the Medicaid application with other social service benefits, such as SNAP and TANF. A couple of participants said they were able to apply for Medicaid and SNAP at the same time and one participant said she got Medicaid when she applied for unemployment benefits during the pandemic.

I have been enrolled since June of this past year, when I was laid off from a job. But I recall the process being fairly, fairly easy actually to get coverage. – 29-year-old, Hispanic male, Oregon

I applied when I found out I was pregnant last year around May, and the process was very easy, I applied online and they contacted me pretty quickly and they sent out everything. – 21-year-old, Black female, Michigan

It’s never been hard for me to fill out an application or anything because the process is easy. Now, everything is online. – 50-year-old, Hispanic female, Tennessee

The process for applying for both me and my husband was extreme. Like they wanted so much paperwork and it took us about two months to finally get qualified for it. – 36-year-old, White female, Ohio

Participants described a range of experiences renewing their Medicaid coverage, but many said the process was simple, particularly during the past few years. While states have not been able to disenroll people from Medicaid, many states have been continuing to process renewals during the continuous enrollment period using ex parte (verifying eligibility through data matches) and through more traditional renewal processes. Many participants said their coverage had been auto-renewed—they described receiving a notice from the state saying their coverage had been renewed for another 12 months—while others described receiving a renewal packet or form in the mail or a notice to complete the renewal form online to maintain their coverage. Still others reported having to submit documentation to the state to confirm continued eligibility. Variation in participant experiences could be due to different renewal policies across states but could also result from different requirements depending on a person’s eligibility pathway. For participants who had to take steps to complete the renewal process, most said they received notices in advance of their renewal date giving them enough time to complete the forms. At least one person noted that if they didn’t respond to the initial notice, the state would usually follow up within another notice or renewal packet. Some who have had Medicaid for a longer time said the process to renew coverage has gotten easier over time.

Every year they sent me something before to sign, and it stated that for renewal, we just want you to go over the details and make sure nothing changed, or if something changed write it down and they have me just sign on paper. And then a couple years after that I started just getting auto renewal notices where they just sent you a piece of mail saying, oh you’ve been renewed and your MediCal is active through the next year. – 32-year-old, Asian male, California

[Medicaid] sent me the form at the beginning of December, and they give you a month. It said, “You have to fill out this form if there have been changes in your household.” I filled out the form, and it gave a deadline. I put the name and everything, and I sent it back. – 39-year-old, Hispanic female (Spanish-speaking), Colorado

When I had Medicaid for the first time…you had to go there, physically, to the office once a year, turn in all your paperwork, and not be missing anything…Recently, for me, it’s been a drastic change because everything is online…I find it super easy, compared to how it was in the past. – 46-year-old, Hispanic male (Spanish speaking), Florida

In managing renewals pre-pandemic, some participants shared that there was a time when they did not receive the renewal packets or notices sent through the mail and either lost coverage for a period of time or nearly lost coverage before renewing. In some cases, participants knew their coverage was about to lapse and contacted their case worker or called the Medicaid agency to complete the renewal over the phone or to request that the renewal information be resent. Other participants said they did not realize their coverage had been terminated until they went to the doctor’s office or hospital. Although participants in these groups did not experience adverse health effects during the gap in coverage, they described feeling stressed and anxious while they tried to get their coverage reinstated.

They’re supposed to send you the renewal packet at least one month in advance to give you time to fill all that out…Unfortunately, the packet never came through, I had to request a new packet, I missed my window. I ended up almost losing my health insurance until I asked my caseworker who…got me the renewal packet, a different one, and the new appointment date and requested an emergency appointment to renew, because just lapsing even a couple of days without insurance can be scary. – 51-year-old, Hispanic male, California

Risks and Challenges Tied to Potentially Losing Medicaid

If they no longer qualified for Medicaid, participants said they would look for coverage through the Marketplaces or possibly from their employer, but affordability was an overriding concern. Most were aware of the health insurance Marketplaces and said they would search for coverage there. Awareness of how to apply for coverage through the Marketplace was fairly high; however, many who previously had Marketplace coverage recounted having difficulty affording premiums and deductibles, even when they had more stable employment. Participants may not have been aware that they might be eligible for zero premium subsidies in the Marketplace since those enhanced subsidies became available in 2021 after many participants had already gained Medicaid coverage. Some said they could potentially obtain insurance through an employer, but worried premiums would not be affordable. Several said they would become uninsured, and some parents said they would forego coverage for themselves but would make sure they could get other coverage for their children. All participants expressed concern over the disruption that losing Medicaid would cause. Even if they could find affordable insurance, they worried about having to find new doctors, particularly for their children.

Yeah, I’d go [to the Marketplace] there to see what plan, and if the price would work for me each month, whether I can afford it. – 56-year-old, Hispanic male (Spanish-speaking), Arizona

I might just have to go through my job’s insurance program they have [if I lose Medicaid]. It’s super expensive but I probably wouldn’t even get insurance for myself. I would just get it for my kids. I just worry about my kids first. – 37-year-old, Hispanic male, Texas

I don’t think [there are other options]. I think when you lose Medicaid, there won’t be anything similar. I think there would be some type of coverage, but it would definitely be at a cost and not with the same coverage as Medicaid. – 39-year-old, Hispanic female (Spanish-speaking), Colorado

I feel like with the cost of everything going up, we’re just breaking even with paying rent and buying groceries. If we were to lose the Medicaid coverage and have to go back to the healthcare Marketplace and have to pay for medical needs, maybe we’ll cover our rent but we’re not going to be able to buy the same groceries. We’re going to have to stretch everything out. We’re not going to have a lot of personal money. It would definitely affect us. – 36-year-old, White female, Ohio

I’d have to go back to what I did before Medicaid. [Being uninsured] is difficult because me and everybody else go to the same free place to get help. So, there’s a long waiting list to get resources and things like that. You’re not guaranteed anything. At least with Medicaid you’re guaranteed you can get medical help. – 60-year-old, White female, Mississippi

Losing Medicaid would pose significant challenges for participants that they said would affect their health as well as their finances. Many participants are managing serious health issues for themselves, their spouses, or their children and losing Medicaid coverage would disrupt their access to care and ability to manage their conditions. They used terms like “terrifying” and “devastating” to describe how they would feel if they no longer had Medicaid. Participants also noted that losing coverage right now, with inflation still relatively high, would create additional financial burdens as they are already struggling to pay current expenses and would have a hard time affording new costs for health insurance. While some worried that they may no longer be eligible due to a change in income, many individuals worried about losing coverage even if their economic circumstance did not change as disenrollments resume for all enrollees over the next 12 to 14 months.

I think it’d affect [me] in every way. Mentally because, obviously, losing a low-cost service and paying for something as costly as private insurance would affect you emotionally, financially. It’s really important right now to have that type of service like Medicaid. – 34-year-old, Hispanic male, Missouri

My baby has to be constantly going in for her checkups. She’s a little baby that’s seen every two months for her shots and everything. I worry because, if she didn’t have Medicaid, maybe I could refrain from going to the doctor. But her shots are a must, so just thinking that she won’t have insurance is something that worries me. – 39-year-old, Hispanic female (Spanish-speaking), Colorado

If it wasn’t for Medicaid, I wouldn’t be able to get the medication I need to function…I mean just to be able to get out of bed and spend time with family, be able to leave the house, I mean it is so important. And I’m scared for all these people because if they lose their Medicaid nine times out of ten, they’re going to be out there without insurance. – 51-year-old, Hispanic female, Texas

[When] my daughter was young we did not have insurance at all. I was a waitress and a single mom, and it was terrifying that I knew every time she got sick, I didn’t have money to take her to the doctor, so I just had to take her into the ER and just get a bill that I knew was going to go to collections because I couldn’t pay it….To being able to be on Medicaid where it’s like okay, you’re sick you need to go to the doctor, let’s go. It goes from this feeling of being like a burden on society and not feeling like you deserve even medical care, to feeling like, ‘Oh I’m a valid human being who I deserve to be able to receive care in this country that we’re in.’– 44-year-old, Black female, Oregon

He [her son] has surgery coming up, but then he also sees a behavioralist, he has childhood anxiety and some other things going on that we have been seeing her for a year, but we’re just really starting to dig in and get things figured out. So, he would lose all of that I feel like because even if I got something through the Marketplace, I don’t know that I would be able to afford to pay copays for all of his visits, because those would add up too. So, yeah it’s just terrifying. It would be devastating. – 39-year-old, White female, Oregon

Looking Ahead

After a three-year pause, states will resume Medicaid disenrollments beginning April 1. All current Medicaid enrollees will undergo a redetermination over the next 12 to 14 months, and unlike during the past three years, enrollees could be disenrolled if they are no longer eligible or if they do not complete the renewal process. While there are federal rules and guidelines about enrollment and renewal processes, how Medicaid enrollees will be affected will vary across states because of differences in renewal polices, outreach and communication strategies, and in the capacity of staff to handle the volume of renewals. State policy choices and how those policies are implemented will be important factors in how many still eligible enrollees are able to retain Medicaid or transition to other sources of coverage if they are not still eligible for Medicaid.

The lack of awareness that Medicaid coverage had been protected during the pandemic and that disenrollments could start in April suggests enhanced communication efforts from states, providers, and community-based organizations using multiple modes may be important. While participants in our focus groups were generally aware of the need to renew their coverage and intended to act in response to a renewal notice, continued state efforts to increase ex parte renewal (automatic renewals using available data) rates and to simplify the process when individuals need to take action to renew their coverage can help promote continuity of coverage for those who remain eligible for Medicaid. States can also adopt strategies to help those who are no longer eligible for Medicaid transition to other coverage options. However, some states may be concerned about the administrative resources required, as well as the costs associated with continued elevated Medicaid enrollment.

Although knowledge among participants about the availability of Marketplace coverage was high, concerns about the affordability of that coverage may prevent people from exploring their options, even though enhanced subsidies have made ACA coverage more affordable. Facilitating account transfers to the Marketplace for people whose Medicaid coverage is terminated and providing information on the availability of enhanced Marketplace subsidies could help increase the number of people who enroll in Marketplace coverage and avoid becoming uninsured.