Long-standing workforce challenges in Medicaid home- and community-based services (HCBS) were exacerbated by the pandemic and addressing them is the top priority for most state HCBS programs. New flexibilities combined with funding provided through the American Rescue Plan Act helped states enact new policies to address those issues during the pandemic, but many of those policies are ending and federal funding will expire. This issue brief describes states’ ongoing efforts to respond to the workforce crunch and how they pay HCBS workers, which are central challenges in ensuring that HCBS services are accessible to the 4 million Medicaid enrollees who use them. The data come from the 21st KFF survey of officials administering Medicaid HCBS programs in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, which states completed between May and August 2023. The survey was sent to each state official responsible for overseeing the administration of HCBS benefits (including home health, personal care, and waiver services for specific populations such as people with physical disabilities). All states except Florida responded to the 2023 survey, but response rates for certain questions were lower. Key takeaways include:

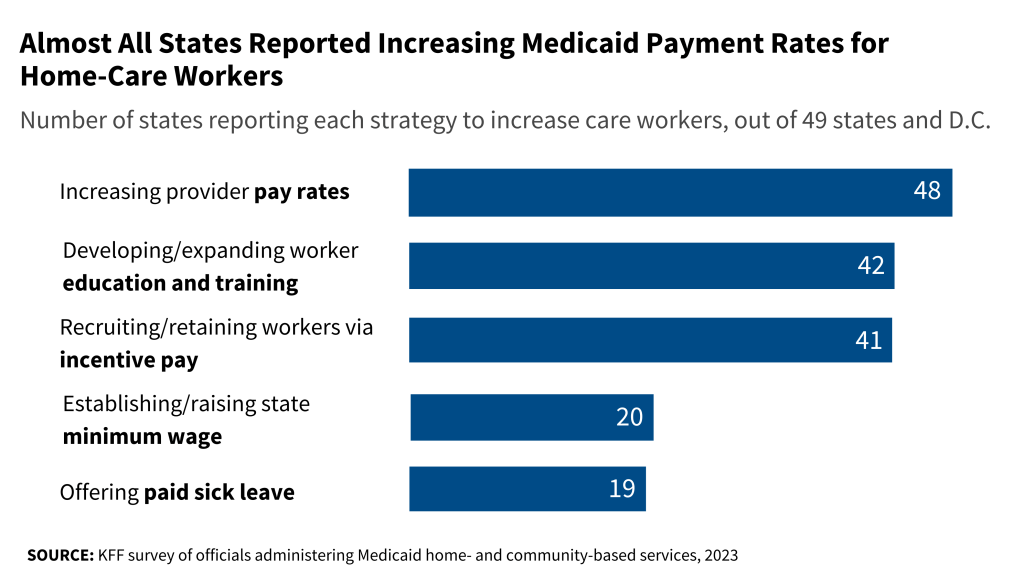

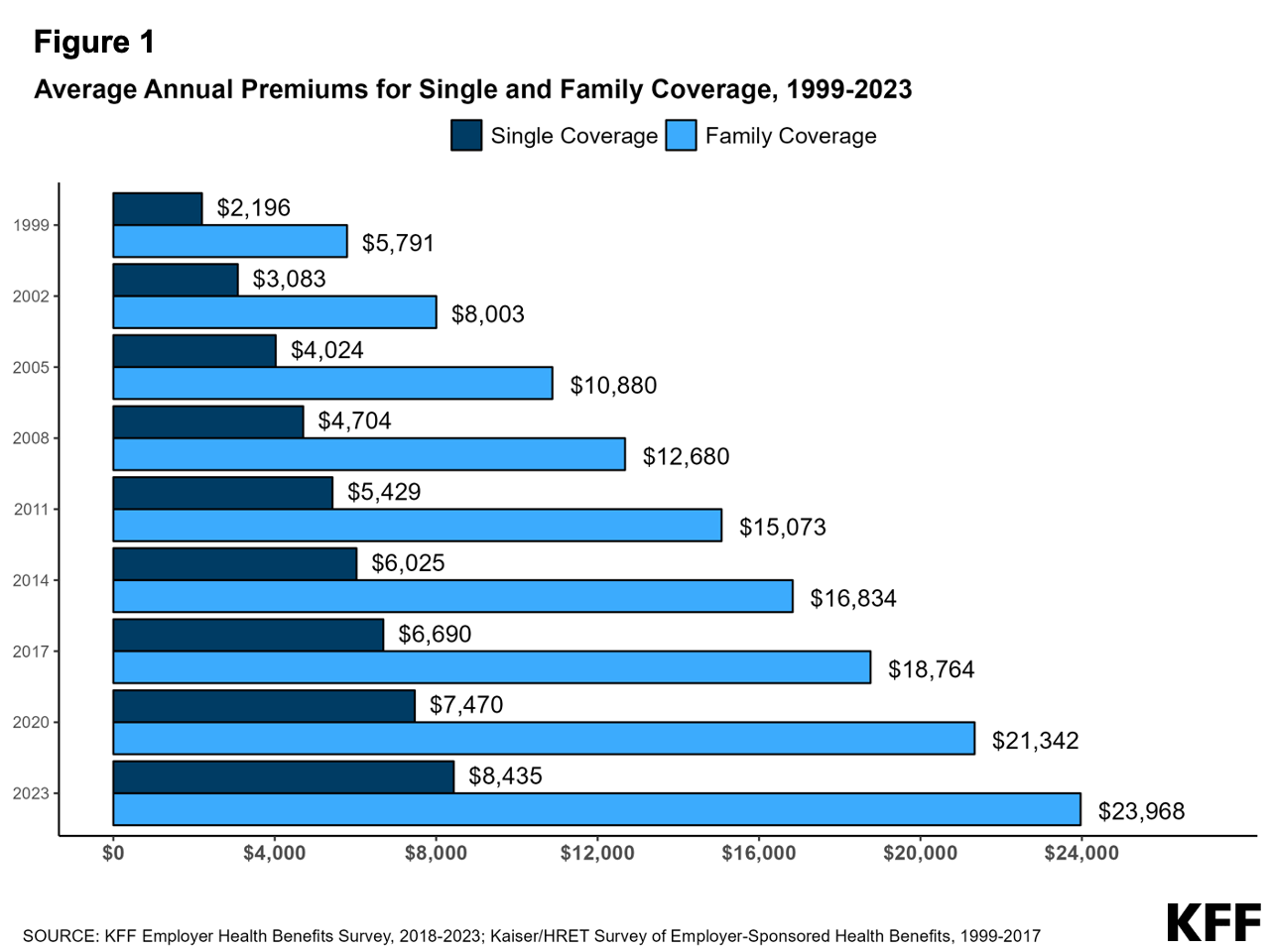

- All responding states (which includes the District of Columbia) reported taking actions to address workforce shortages, including raising payment rates in most states (Figure 1).

- All states reported shortages of HCBS workers, most frequently among direct support professionals, personal care attendants, nursing staff, and home health aides.

- Most (43) states reported permanent closures of HCBS providers within the last year.

- Among the 34 states that reported time-based payment rates for personal care providers, most pay less than $20 per hour.

What are Medicaid HCBS and how are they provided and paid for?

HCBS are one type of long-term services and supports (LTSS), which encompass a broad range of paid and unpaid medical and personal care services. LTSS assist with activities of daily living (such as eating, bathing, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals, managing medication, and housekeeping). They are provided to people who need such services because of aging, chronic illness, or disability and may be provided in institutional settings such as nursing facilities or in people’s homes and the community. Services provided in non-institutional settings are usually referred to as HCBS and include a wide range of services such as adult daycare, home health, personal care, transportation, and supported employment. A wide variety of workers provide HCBS, and most positions require minimal training and education (see Box 1). In 2020, Medicaid was the primary payer for LTSS, covering over half of all spending in in the U.S.

Box 1: The HCBS Workforce

The HCBS workforce is diverse and encompasses individuals with a variety of job titles. Depending on the state and the specific services offered, the people who provide HCBS include personal care aides, direct support professionals, home health aides, certified nursing assistants, and independent providers. Different types of providers are paid differently and are subject to different training and certification requirements. Home health aides and certified nursing assistants are the only types of providers that must comply with federal training and certification standards.

- Personal care aides assist with the activities of daily living, housekeeping tasks, meal preparation, and medication management.

- Direct support professionals provide a broader range of services than personal care aides such as employment supports.

- Home health aides and certified nursing assistants provide clinical care in community settings and help with the activities of daily living.

- Independent providers are employed directly by the people who are receiving HCBS through what are called “self-directed services.” Some independent providers are family caregivers, who may be paid by the Medicaid program for the services they provide.

People who provide HCBS are nearly all female (85% in 2021) and nonwhite. Most have less than an associate degree and although over half work full time, many receive public assistance such as Medicaid or food and nutrition assistance.

All HCBS are optional except for the mandatory home health benefit, and most benefits—including personal care—first became available through optional Medicaid “waiver” programs. If services are provided through a state plan, they must be offered to all eligible individuals. In contrast, services provided under waivers, such as 1115s or 1915(c)s, may be restricted to specific groups based on geographic region, income, or type of disability. Waivers may also include a wider range of service types than can be provided under state plans. Because all HCBS besides home health were first available through waivers, services were generally tailored to certain types of Medicaid enrollees such as those with intellectual disabilities or those with physical disabilities, and benefit packages were also specific to those groups’ needs. Many HCBS are now available through Medicaid state plans and available to all enrollees in the state. KFF estimates that over 4 million Medicaid enrollees use HCBS, and that the numbers of people using HCBS through the state plan are similar to the numbers using HCBS through waivers.

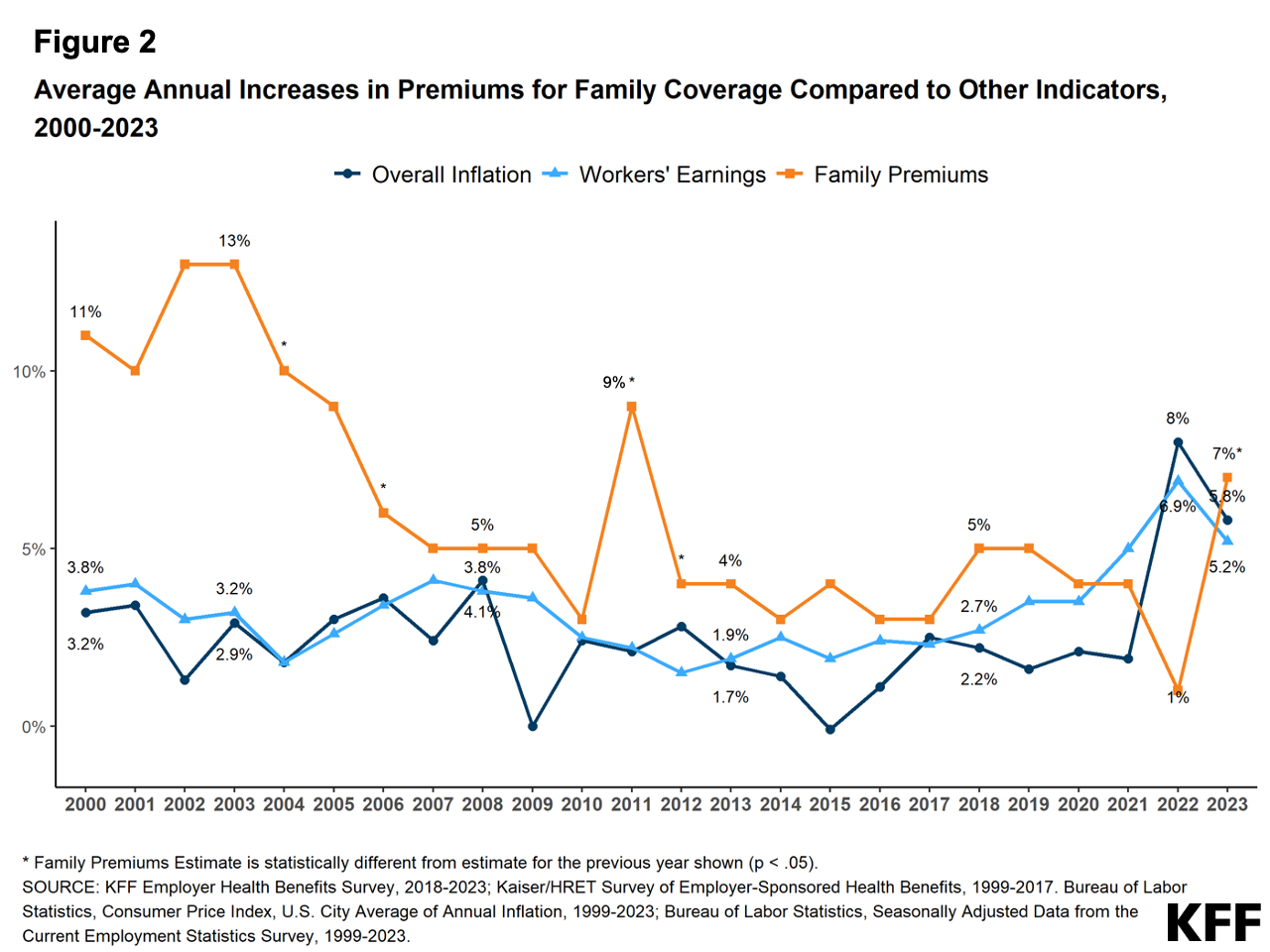

In KFF’s 2023 survey of state HCBS programs, all states reported offering personal care and other optional HCBS, most commonly through 1915(c) waivers (Figure 2, Appendix Table 2). States are required to offer home health through their Medicaid state plan and 34 states also offer personal care through the state plan. All states also offer HCBS waivers—either an 1115 waiver (14 states with one waiver in each state) and/or a 1915(c) waiver (47 states and 258 waivers total). Most 1915(c) waivers serve specific populations, with 47 states having waivers for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities and 42 states having waivers for people who are ages 65 and older or have physical disabilities. Ohio was the only state to report a new 1915(c) waiver in 2023, serving people under age 21 who have complex behavioral health needs that would require an inpatient level of psychiatric care.

Over half of states use managed care to provide at least some HCBS, particularly for benefits provided through the state plan or 1115 waivers. In managed care, states pay managed care plans a set fee—often called a capitation payment—for each person enrolled and the managed care plans are responsible for providing all services to enrollees. Use of managed care to provide HCBS has been growing over time, with states using managed care to make their Medicaid spending more predictable and to help coordinate the services enrollees use. Among the 14 states with 1115 waivers, 10 use managed care plans to provide at least some of the HCBS and over half of states use managed care plans to provide at least some home health and personal care. Managed care was much less common under the 1915(c) waivers, particularly for waivers serving people with intellectual or developmental disabilities—of the 47 states with such waivers, only 6 provided any of the benefits through managed care.

How are states addressing the workforce challenges in HCBS?

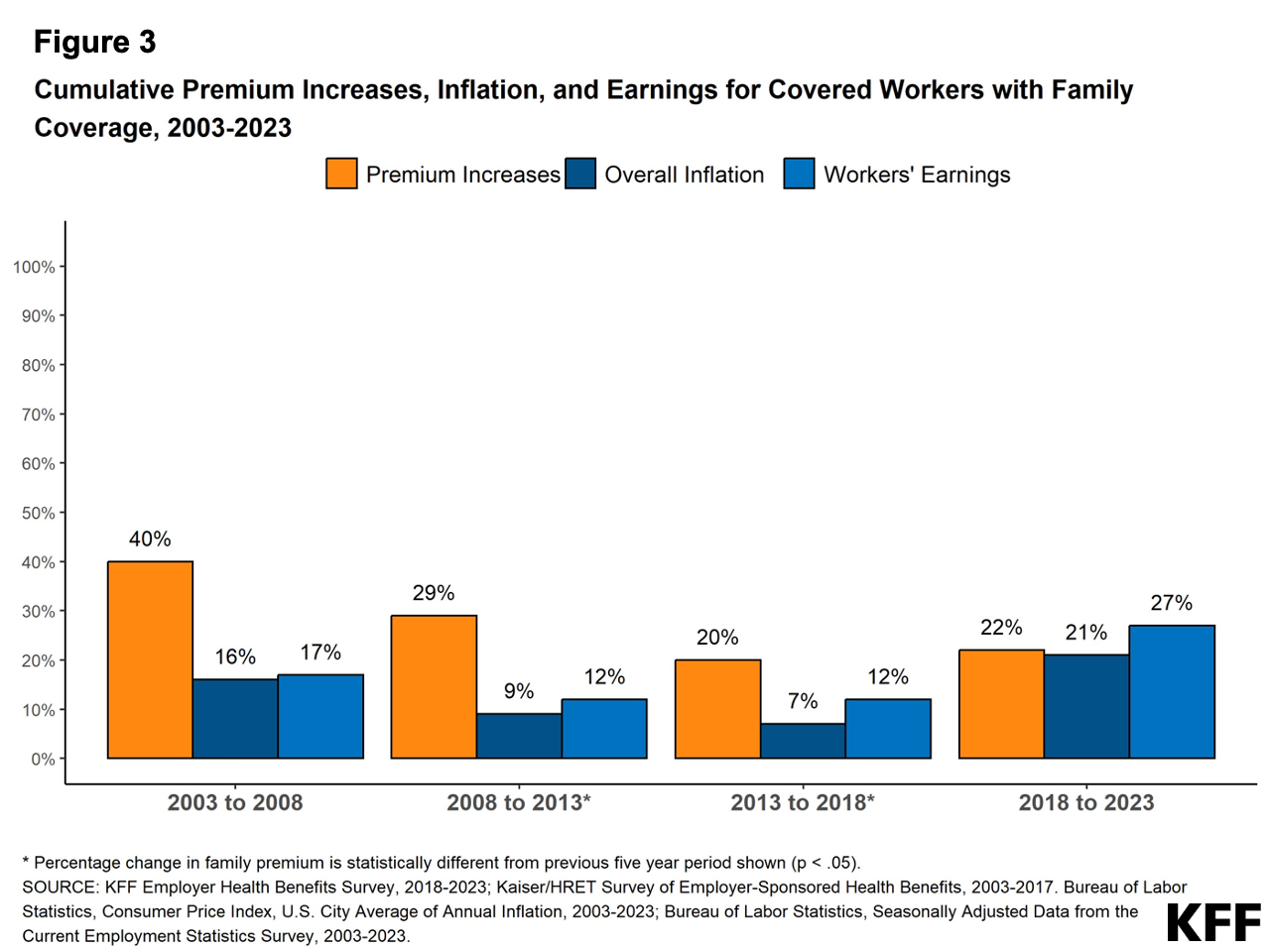

All responding states reported workforce shortages in 2023, with the most common shortages being among direct support professionals (50 states), personal care attendants (49 states), and nursing staff (49 states) (Figure 3, Appendix Table 3). States were asked if they had shortages of each type of provider but were not provided with a definition of shortage. Most states also reported shortages in home health aides (47 states), case managers (45 states), community-based mental health providers (38 states), and occupational, physical, and speech therapy providers (35 states). In some cases, states may not have reported a shortage of a particular type of provider because that type of service is not offered through the HCBS program.

All states but one (Nebraska) reported shortages for more than one type of provider and 48 states reported shortages among five or more provider types. Such shortages may reflect ongoing effects from the pandemic, but also low levels of compensation coupled with increasing requirements of providers. In the summer of 2021, HCBS providers in focus groups reported that their jobs had high physical demands and mental demands that were often “overwhelming.” The groups described their wages as low, particularly given the demands of their jobs; and how staffing shortages made their jobs harder because they may not know if they would be able to leave work at the end of their shift. Similarly, in the 2023 survey, California reported “difficult finding qualified providers due to low Medi-Cal reimbursement rates, losing providers due to Electronic Visit Verification (EVV) requirements, and finding qualified homemaker and attendant care providers post-COVID.” (Electronic visit verification requires providers to document electronically the services provided, the recipient, the provider, and the time, date, and location of services. The federal requirement took effect in January 2020 for personal care and in January 2023 for home health services.)

Within the last year, 43 states experienced permanent closures of HCBS providers, which were most common among adult day health programs (32 states), group homes (29 states), and assisted living facilities (27 states) (Figure 4, Appendix Table 4). States were asked if there were any permanent closures of providers within each type of setting that provides HCBS. Between 10 and 20 states reported closures of supported employment providers (19 states), providers working in enrollees’ homes (18 states), community mental health providers (14 states), and home health agencies (11 states). Arizona and Tennessee reported that closures were unknown to the state.

Most states reported closures among more than one type of provider: 37 states reported closures among two or more provider types, 23 states reported closures among 4 or more provider types, and 1 state (Maine) reported closures among all eight provider types. Some closures reflect provider shortages: Minnesota reported that “providers have downsized to coordinate locations due to staffing shortages.” On the other hand, some closures reflect the fact that many companies struggled during the pandemic and have not recovered: Louisiana reported that day services were not a feasible business model during the pandemic because of “limited to no attendance.” (Day services, also known as day care, are provided to people in centers rather than in people’s homes. The services are intended to support independence and socialization while also providing family caregivers with a break during the day.)

All responding states reported taking actions to address provider shortages, with 48 states increasing payment rates, 42 states developing or expanding worker education and training programs, and 41 states offering incentive payments to recruit or retain workers (Figure 1, Appendix Table 1). Less common initiatives included establishing or raising the state minimum wage (20 states) and offering paid sick leave for workers (19 states). States also reported several other types of initiatives to strengthen the workforce, including creating platforms or support systems to connect job seekers with employers and positions, launching a social media campaign, and providing outreach to prospective employees.

Some states have permanent payment rate increases in place for providers, but 13 states reported that payment rate increases for at least some of the workers were temporary. Only 14 states have payment formulas that automatically increase with the costs of living, but those formulas do not apply across all types of workers.

How much do states pay for Medicaid HCBS?

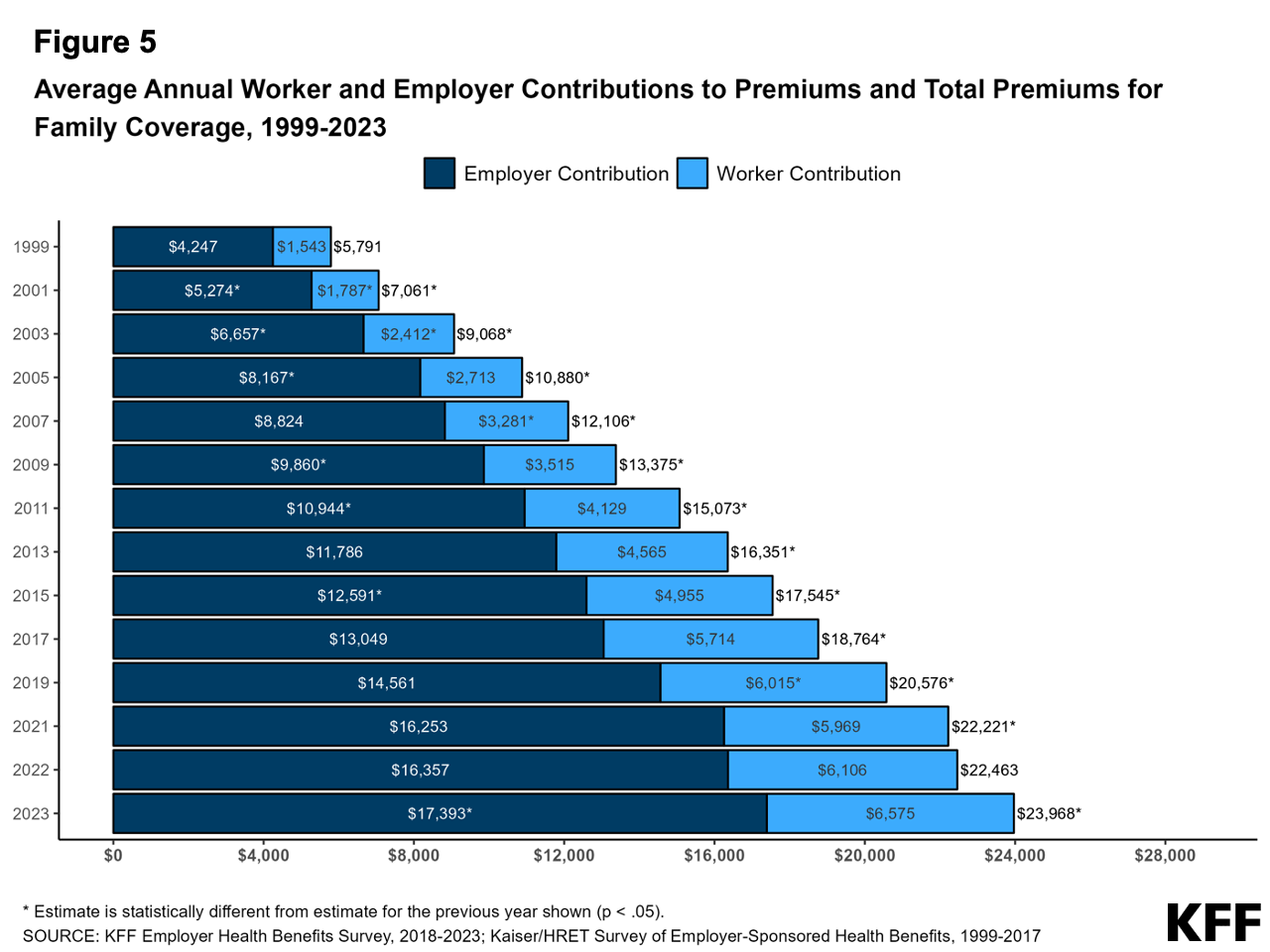

KFF asked states to report their average dollar rate per visit paid to two types of HCBS provider agencies (personal care agencies and home health agencies) and three types of specific HCBS providers (personal care providers, home health aides, and registered nurses), but many states were unable to report all rates (Figure 5, Appendix Table 5). The number of states that did not provide payment rates or reported that payment rates were unknown was 8 for personal care agencies and 24 for home health agencies. Even more states did not provide payment rates for specific provider types: For each specific type of provider, nearly half of states did not provide payment rate information or reported that payment rates were unknown.

If provisions of a proposed Biden Administration rule are finalized, states would be required to report such detailed payment rates (see Box 2). If that rule is finalized as proposed, states would be required to report payment rates for certain HCBS and to demonstrate that at least 80% of the payments went to compensation for providers, also described as “direct care workers.” Meeting that requirement would require states to know both agency and provider payment rates. Among the states that were able to report payment rates, only 15 could report payment rates for personal care agencies, home health agencies, personal care providers, and home health aides, all of which would be required under the rule. Those 15 states include states that reported a mix of time-based and visit-based rates, which makes comparisons between provider and agency rates more complicated. Given the challenges for states in collecting such data, federal guidance might be required to achieve consistent reporting across states.

Box 2: Proposed Rule on Access to HCBS

On May 3, 2023, the Biden Administration released a proposed rule aimed at ensuring access to Medicaid services, which has several notable provisions aimed at addressing HCBS workforce challenges. States would be required to report payment rates for personal care, home health aide, and homemaker services to increase transparency around payment rates. For services provided through 1915(c) waivers and through the 1915 state plan authorities, the proposed rule has additional requirements related to the HCBS workforce, including the following.

- The proposed rule would require states to demonstrate that payment rates are “adequate to ensure a sufficient direct care workforce to meet the needs of beneficiaries and provide access to services in the amount, duration, and scope specified in the person-centered plan.”

- The rule would also require states to demonstrate that at least 80 percent of total payments for homemaker services, home health aide services, and personal care services are compensation to direct care workers.

- States would be required to report the number of people on waiting lists for services.

- States would also have to report the average amount of time from when homemaker services, home health aide services, or personal care services are initially approved to when services begin and the percentage of authorized hours that are provided.

The proposed rule also includes provisions that would strengthen requirements around person-centered planning and needs assessment, create new requirements around incident management, establish requirements for people to file grievances if they are receiving HCBS from the state Medicaid program, and require states to report on nationally-standardized quality measures. Provisions would take effect on a rolling basis, between 2 and 4 years after the rule is finalized.

States reported many reasons why it was difficult to report payment rates, including the following.

- Some states reported that services were bundled together in various ways and therefore, the payment rates were not distinguishable. For example, New Hampshire wrote: “as personal care is not a distinct service, this data cannot be determined.”

- Among states with managed care, some states responded that they did not know the payment rates for agencies because the services were paid for by managed care plans and they did not have access to those payment rates.

- Other states responded that they knew the payment rates for agencies but not what the agencies paid their direct care workers. Multiple states reported that they do not “dictate” what agencies pay to providers or that individual providers negotiate their own payment rates with the agencies.

- Still other states reported that payment rates were too varied across providers and individuals. For example, Indiana reported that payment rates varied from $400 to $6,000 per month: That variation reflected the fact that there are over 400 personal care agencies, and each person has different levels of needs which vary week to week. Hawaii reported that visits vary in terms of what is provided and that the five managed care plans providing HCBS use different methodologies for collecting data, making it impossible to provide “an accurate dollar average.”

In addition to having difficulty reporting payment rates, many states reported different payment rates for personal care across different waivers and the waiver payment rates often differ from the payment rates for personal care provided through the state plan. When states reported multiple payment rates for personal care, KFF used the median of those payment rates in the analysis.

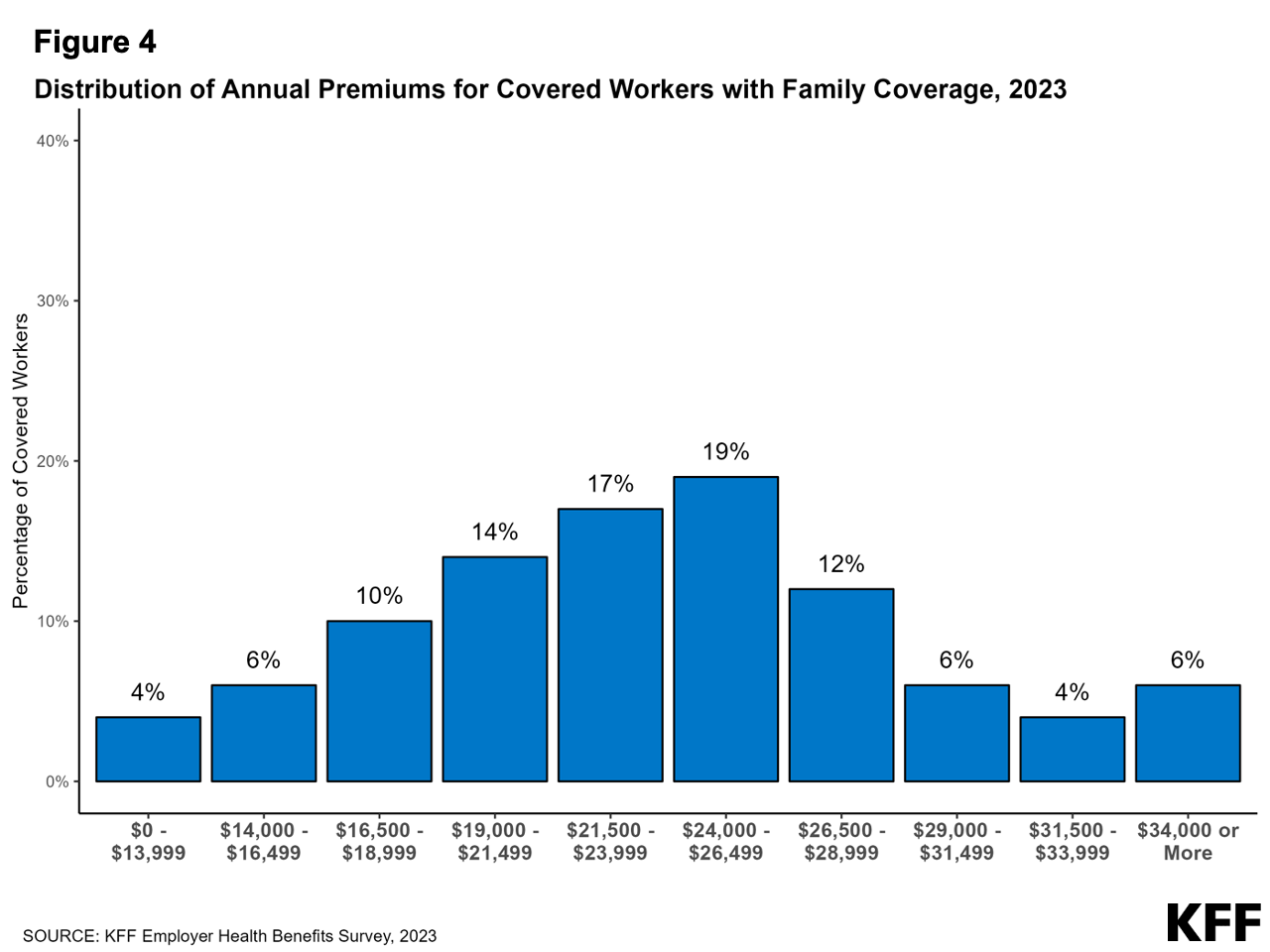

Although KFF asked states to report the average dollar rate per visit, states varied in their reporting of payment rates, with most states reporting payment rates by time (either 15 minutes or one hour), and a smaller number of states reporting rates that were per visit or per day. Most states reported payment rates by time and among those states, payments for personal care workers are generally below $20 per hour. Rates for home health aides are somewhat higher, reflecting the additional training requirements for such workers. Among the states with payment rates in the highest category, some reported that the rates were per visit or per day. Others did not indicate whether their rates were based on time or another basis, but it is likely that most payment rates in the highest category are per visit or per day.

Payment rates to home health agencies are generally larger than those to personal care agencies, but there is considerable variation in both (Figure 6). Across the states, the median hourly payment rates to home health agencies range from $27 to $149 among most states whereas those for personal care agencies range from $10 to $36.

The payment rates to HCBS providers also show considerable variation and are somewhat higher than those reported by other organizations on account of differences in reporting and provider categorization (Figure 6). KFF’s survey estimates that median payment rates to providers are $19 per hour for personal care providers, $28 for home health aides, and $43 for registered nurses. It is difficult to compare those numbers to those of other organizations for the following reasons.

- Other organizations group classes of providers together differently. PHI recently reported that in 2022, home care workers made an average of $14.50 per hour and residential care aides made $15.39 per hour. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports $14.51 per hour for home health and personal care aides in 2022.

- Other organizations include payment rates for workers regardless of the source of payment whereas KFF rates only reflect the Medicaid rates and Medicaid often covers more intensive personal care services than other payers.

Among states that deliver HCBS through managed care, 20 states reported that the fee-for-service payment rate is the minimum amount MCOs could pay providers. Out of the 36 states that use managed care to provide at least some HCBS, none of the states reported that fee-for-service rates were the maximum amount that managed care plans could pay providers. There were 20 states that reported fee-for-service rates were the minimum payment rates, 13 states that reported there was no relationship between the fee-for-service and managed care rates, and 3 states that reported the answer was unknown or did not respond to the question. Even among states that do not directly tie fee-for-service rates to managed care rates, the fee-for-service rates may affect negotiations between health plans and HCBS providers, thereby, affecting the managed care rates. For example, Texas reported that “the Medicaid fee schedule serves as a primary negotiating tool for both MCOs [managed care plans] and providers in Texas. Many MCO/provider reimbursement contracts are directly tied to the Medicaid FFS [fee-for-service] fee schedule through established percentages (e.g., 100%, 102%, 95%, etc.). Furthermore, it is common for provider reimbursement contracts that are directly tied to the Medicaid fee schedule (i.e., set at a % of Medicaid) to automatically adjust when the Medicaid fee schedule changes.”

What may happen to the Medicaid HCBS workforce in the next few years?

How does the workforce shortage for Medicaid HCBS fit in with the broader staffing challenges for long-term services and supports (LTSS)? Recent analysis on the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker shows that, as of June 2023, the number of workers in LTSS settings was measurably lower than in early 2020. Shortages and high turnover among LTSS workers reflect demanding working conditions and relatively low wages. The Biden Administration has released a proposed rule that would increase nursing facility staffing levels. KFF analysis shows that fewer than 1 in 5 nursing facilities would currently meet the levels of staffing that have been recommended, and concerns have been raised that there are not enough workers for nursing facilities to hire. Immigrants could help fill some of those positions, but a backlog of green card petitions prompted the State Department to cutoff eligibility for anyone who applied after June 1, 2022. There are concerns that the freeze on green card petitions will further exacerbate nursing shortages across both health and long-term care sectors. These challenges will only grow as the population ages: Arizona estimates that it will need to increase the workforce by over 35,000 positions to meet the demands of a growing population of older adults. Such factors highlight that the workforce crisis in Medicaid HCBS is part of an overall crisis in the LTSS sector.

How will states continue to address workforce challenges in Medicaid HCBS as pandemic-era flexibilities and funding come to an end? Many of the payment rate increases and bonuses for retention and recruitment were funded by extra federal funding available through the American Rescue Plan Act, but as that funding expires, states will have to find alternative funding sources if they want to maintain spending levels. The state of New York reported: “Workforce issues are paramount and the State is making major investments to strengthen the workforce through APRA [American Rescue Plan Act] initiatives.” States also used pandemic-era authorities to expand access to HCBS, in particular, by allowing family caregivers to be paid providers and increasing payment rates. Those authorities will all end by November 11, 2023, and it is unknown whether the expiration of those authorities will increase challenges in accessing Medicaid HCBS.

How will proposed requirements for reporting LTSS payment rates affect states’ payments for Medicaid LTSS? Current proposed rules aim to address workforce shortages in the nursing facility and HCBS sectors by requiring states to report more information about Medicaid payment rates and the percentage of states’ payments that go towards worker compensation. It is unknown how requirements in the final rules will compare with the proposed rules (including the timeline for states to meet the new requirements), and whether reporting requirements will affect the ways in which states pay for LTSS. Both new rules are likely to put upward pressure on payment rates and spending on LTSS but there is no new federal funding for Medicaid’s costs, which are shared between the federal and state governments, so it is unknown where the new funding may come from. Also unknown is whether the need to report payment rates could deter states from pursuing alternative payment approaches such as value-based care or bundled payments, which aim to promote improved health and well-being for people but often obscure payment rates for specific services or providers.