Early Look at Medicaid Spending and Enrollment Trends Amid COVID-19

The coronavirus pandemic has generated both a public health crisis and an economic crisis, with major implications for Medicaid, a countercyclical program. During economic downturns, more people enroll in Medicaid, increasing program spending at the same time state tax revenues may be falling. To help support states as enrollment in Medicaid grows and ensure existing enrollees maintain continuous coverage, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) authorized a 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal match rate (“FMAP”) (retroactive to January 1, 2020) available if states meet certain “maintenance of eligibility” (MOE) requirements.

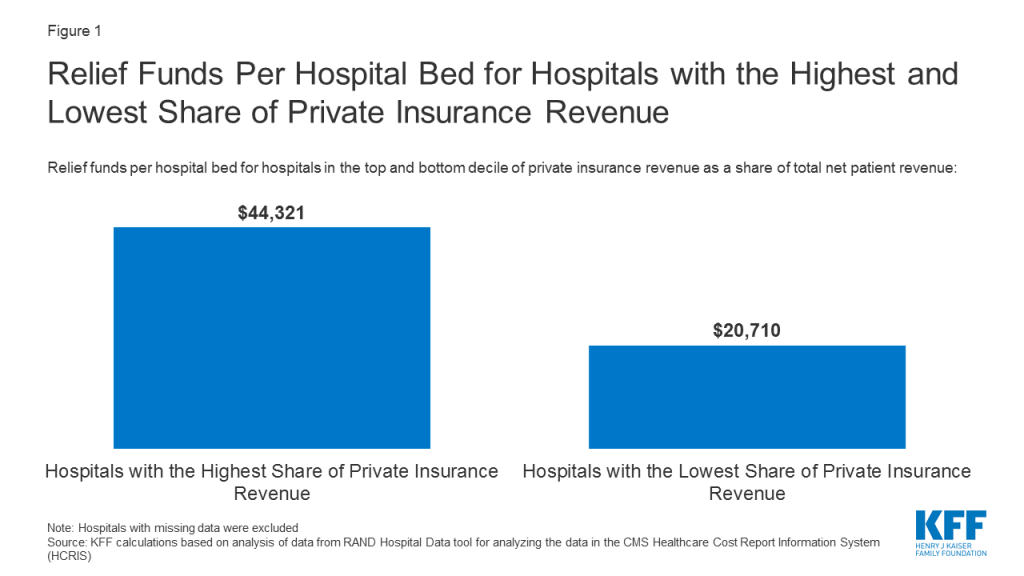

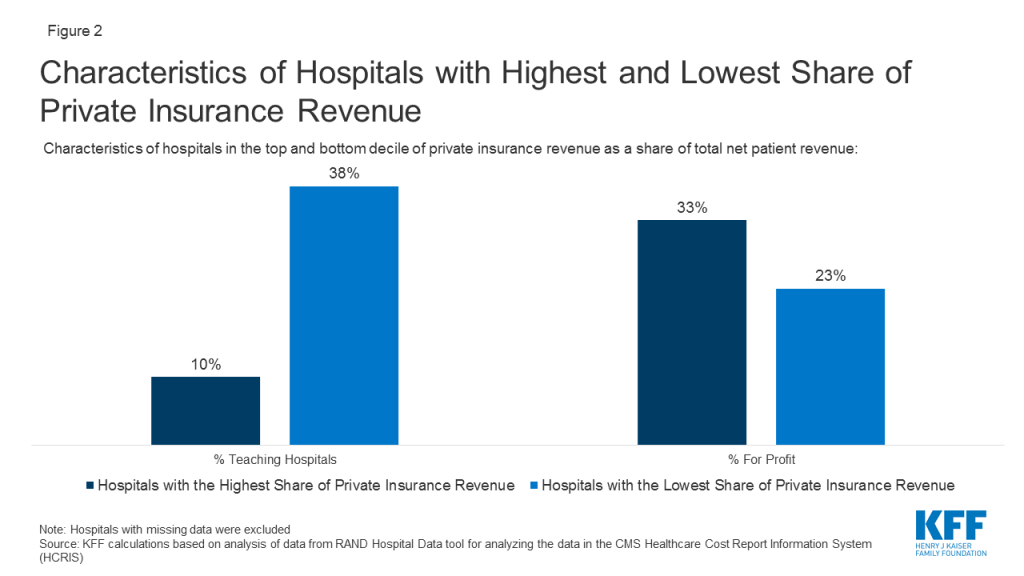

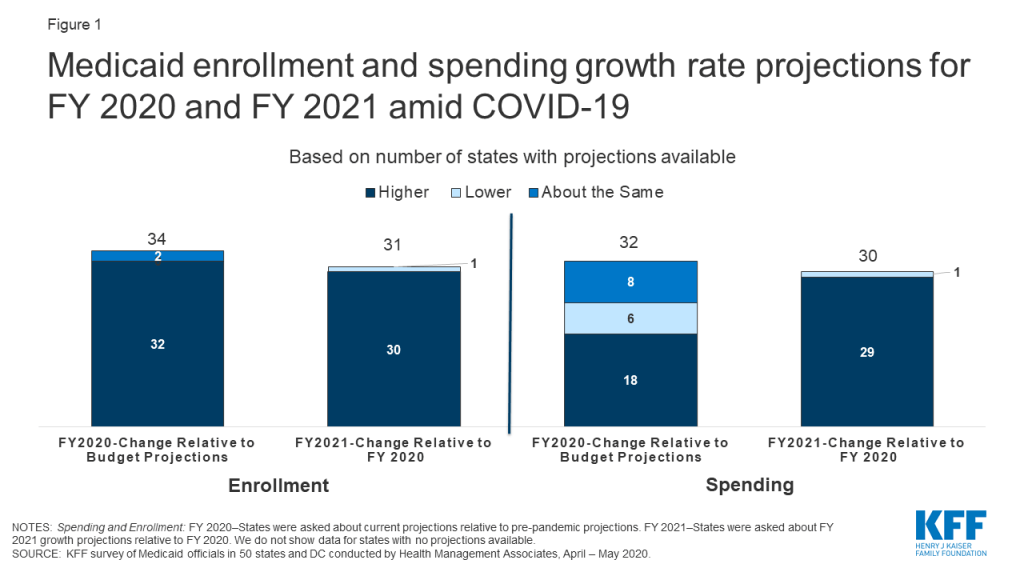

This brief provides some early insights into the current picture of Medicaid spending and enrollment, as Congress considers providing additional fiscal relief through the federal Medicaid match rate. It is based on a rapid survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA) of Medicaid directors in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. A total of 38 states responded to the survey. Some states were still in the process of gathering data to understand the implications of the coronavirus at the time of this survey and did not have updated enrollment and/or spending projections yet for state fiscal year (FY) 2020 and/or FY 2021. Overall, nearly all states with enrollment projections and over half of states with spending projections anticipate FY 2020 growth rates to exceed pre-pandemic estimates. Nearly all states with projections anticipate FY 2021 growth rates to exceed rates in FY 2020 for both enrollment and spending (Figure 1). For most states, the fiscal year begins on July 1.

Overview

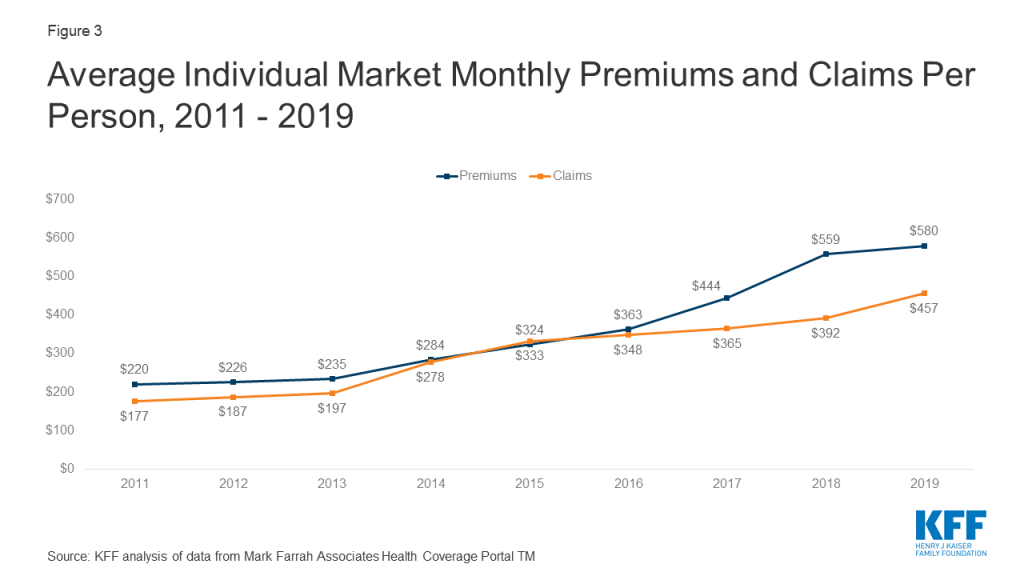

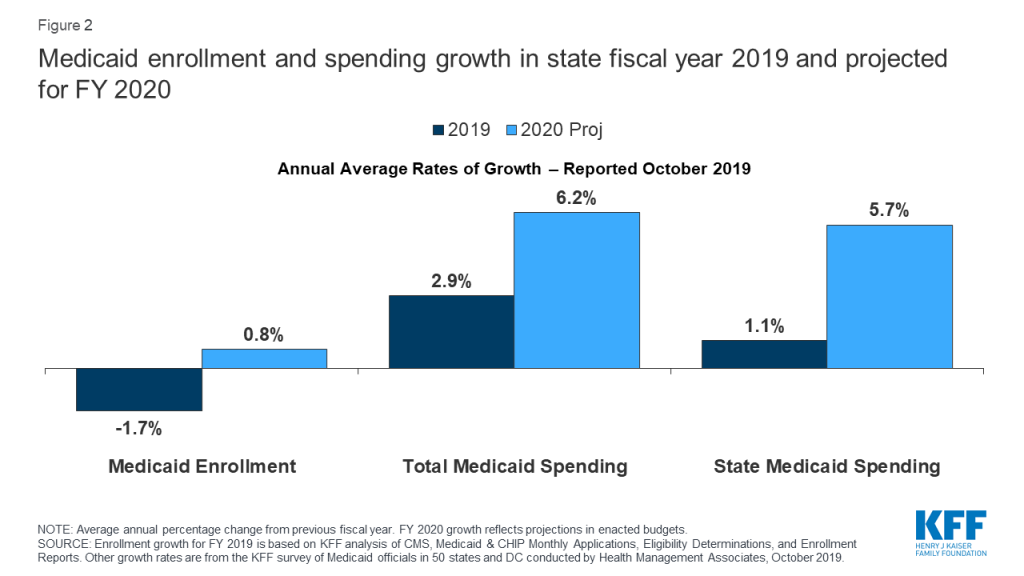

At the start of FY 2020, states anticipated relatively flat enrollment growth but modest total and state Medicaid spending growth (Figure 2). When states adopted budgets for FY 2020, states attributed flat enrollment projections primarily to a robust economy. States also pointed to changes in renewal processes, new functionality of upgraded eligibility systems, and enhanced verifications and data matching efforts as contributors to enrollment declines. While states expected flat enrollment growth to mitigate total Medicaid spending growth, states also reported that higher costs for prescription drugs, provider rate increases, and costs for the seniors and people with disabilities (including increased utilization of long-term services and supports) would put upward pressure on total Medicaid spending.

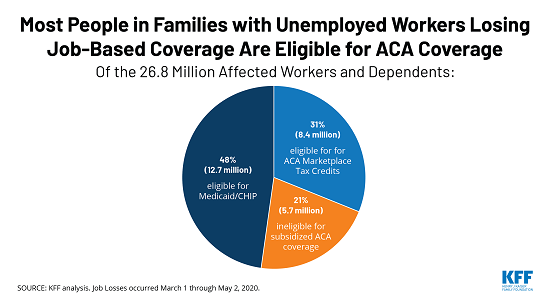

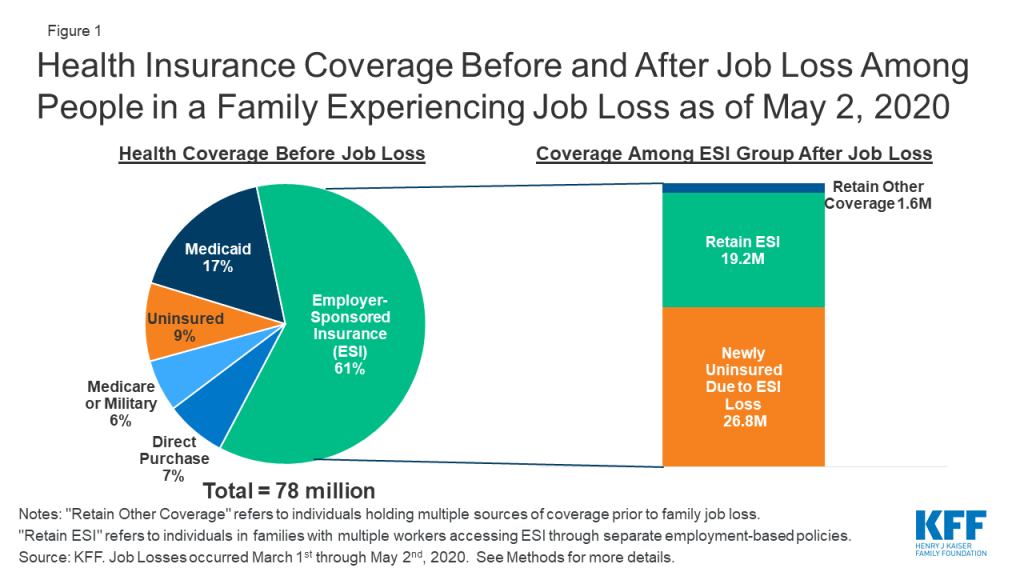

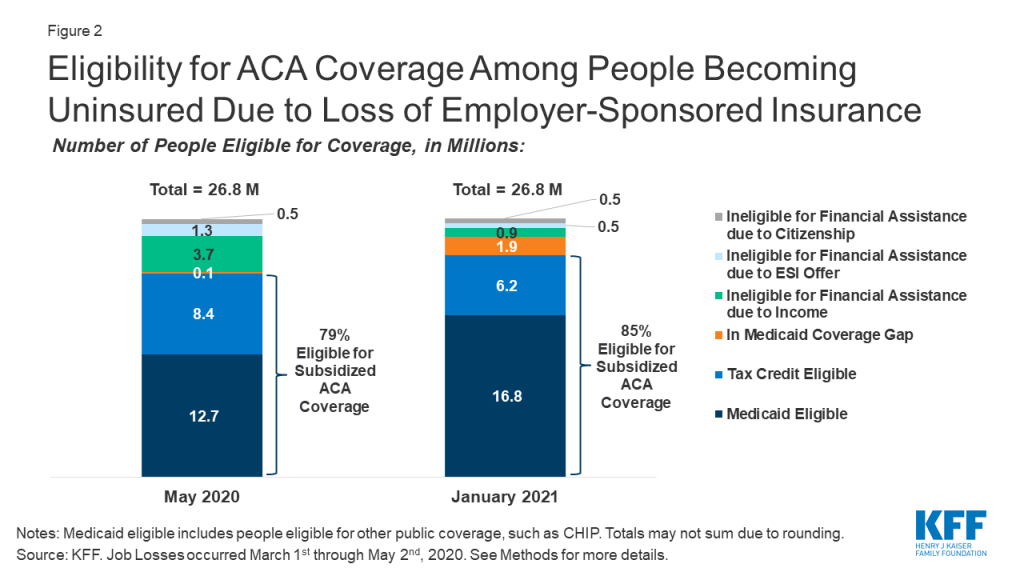

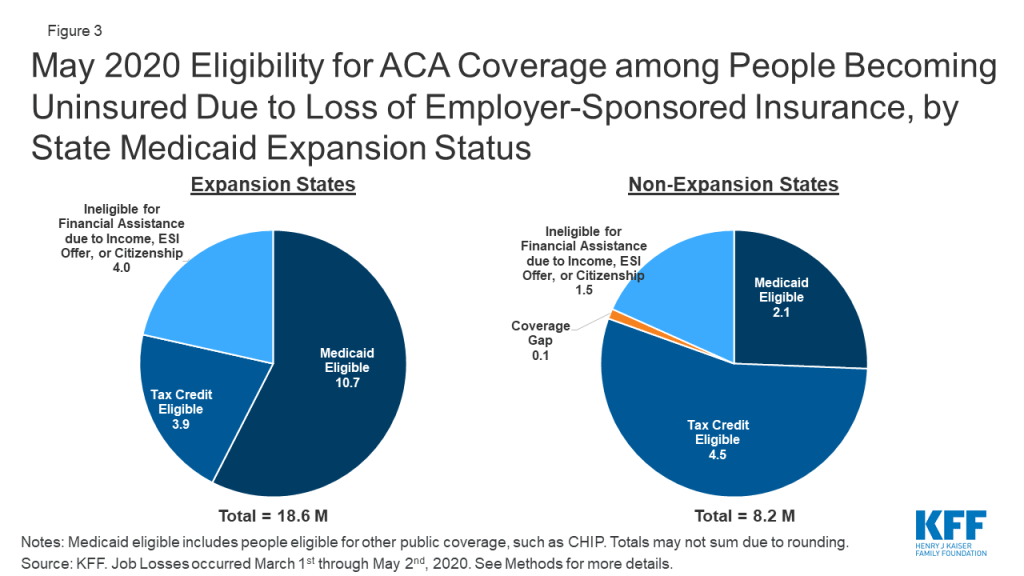

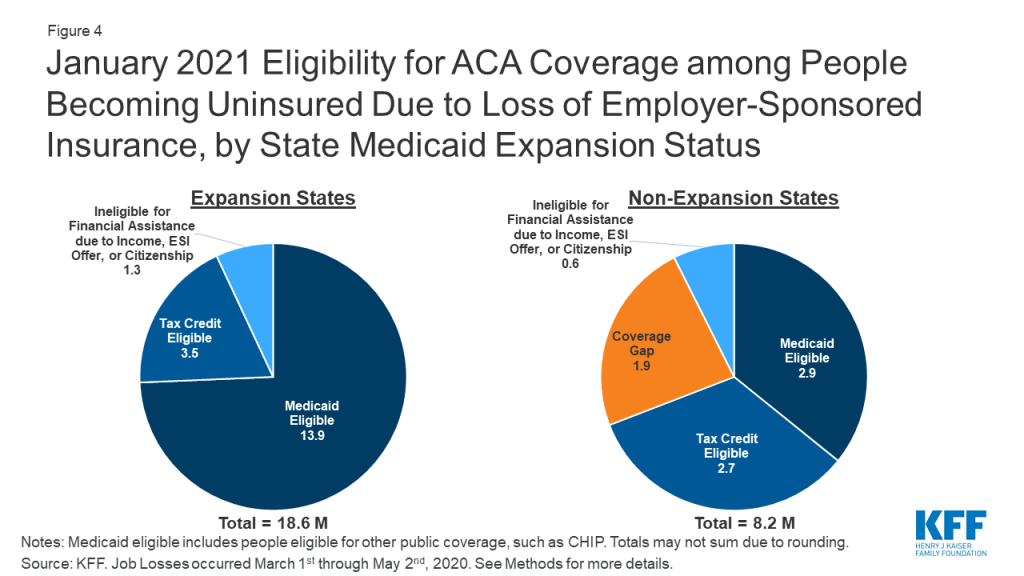

The economic implications from the coronavirus pandemic are stark with unemployment rates up and state revenues down. April data show that the U.S. economy lost 20.5 million jobs and the unemployment rate increased to 14.7 percent. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the unemployment rate will average 15 percent during the second and third quarters of 2020, up from less than 4 percent in the first quarter. CBO expects the unemployment rate to decline somewhat but remain at 9.5 percent by the end of 2021 (about 6 percentage points higher than the rate in CBO’s economic projection produced in January 2020). Often individuals lose job-based health insurance coverage when they experience job loss. A recent KFF analysis shows that by January 2021, when unemployment insurance benefits cease for most people who lost jobs between March 1 and May 2, 2020, nearly 17 million people could be newly eligible for Medicaid and about 6 million eligible for marketplace subsidies (assuming individuals in this group have not found work as by that time) . Preliminary data show that state April 2020 revenues may be down 20 percent to 50 percent from April last year and down significantly relative to pre-pandemic projections. Drops in revenues coupled with increased demand for spending to address the public health emergency is generating budget shortfalls across states. A CBO letter to the Chair of the House Budget Committee affirms that without further funding from the federal government, states will need to increase taxes or reduce spending as a result of the pandemic and these actions would result in lower spending and higher job loss.

During economic downturns, enrollment and spending in Medicaid grow. During downturns, more individuals lose jobs and income and enroll in Medicaid. While demand for Medicaid and other services typically increases during downturns, state revenues generally fall. For example, during the Great recession, the unemployment rate peaked at 10 percent in October 2009 and Medicaid spending and enrollment growth peaked at 7.6 percent and 7.8 percent, respectively, in 2009 as well. At that time, a temporary increase in the Medicaid FMAP rate was used to provide rapid fiscal relief to states. This approach leveraged Medicaid’s existing financing structure to provide federal funds to states more quickly and efficiently than establishing a new program or allocating money from a new funding stream. It also reduced the need for states to cut Medicaid spending to fill state budget gaps and included MOE provisions for states to be eligible for enhanced match. Because Medicaid is funded from a combination of federal and state funds, states need to make substantial cuts to Medicaid to generate state savings. For example, for a state with a 50 percent match rate, a $100 cut to Medicaid will reduce state spending by $50 and federal spending by $50. However, for the ACA expansion population, a $100 reduction will yield only $10 in state savings and reduce federal spending by $90 (as the federal match rate is set at 90 percent for newly eligible expansion adults).

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, amended by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, authorizes a 6.2 percentage point increase in federal Medicaid matching funds to help states respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The additional funds are available to states from January 1, 2020 through the quarter in which the public health emergency period ends, provided that states meet certain conditions. The HHS Secretary declared COVID-19 a nationwide public health emergency on January 31, 2020, retroactive to January 27, 2020. The public health emergency ends when the Secretary declares that the emergency no longer exists or after 90 days, whichever happens first, although the Secretary can renew the public health emergency declaration for subsequent periods. The public health emergency was extended on April 26 for another 90 days. Increased federal matching funds support states in responding to the increased need for services, such as testing and treatment during the COVID-19 public health emergency, as well as increased enrollment as more people lose income and qualify for Medicaid during the economic downturn.

States must meet five maintenance of eligibility (MOE) conditions that ensure continued coverage for current enrollees to receive the enhanced federal matching funds during the COVID-19 public health emergency. States must apply Medicaid eligibility standards, methodologies, and procedures that are no more restrictive, and states cannot increase premiums relative to what was in effect on January 1, 2020. States also must cover coronavirus testing and COVID-19 treatment, including vaccines, specialized equipment, and therapies, without cost-sharing while they receive the increased funds. States also cannot increase political subdivisions’ contributions to the non-federal share of Medicaid costs beyond what was required on March 11, 2020. Finally, states must provide continuous eligibility through the end of the month in which the public health emergency ends for those enrolled as of March 18, 2020 unless the person ceases to be a state resident, becomes deceased, or requests a voluntary coverage termination. Medicaid eligibility during this time must continue “regardless of any changes in circumstances or redeterminations at scheduled renewals that would otherwise result in termination.” Recent guidance from CMS states that, under the MOE, states that accept the FMAP increase cannot increase cost-sharing.

Key Findings

Enrollment Trends

Compared to pre-pandemic estimates, nearly all states with projections anticipate higher enrollment growth in FY 2020 and continued growth into FY 2021. We asked states about their current projections for monthly Medicaid enrollment for May 2020 relative to projections made prior to the pandemic as well as the direction and drivers of enrollment into FY 2021. Not surprisingly, nearly all states with projections (32 of 34) anticipate that current FY 2020 enrollment growth will exceed pre-pandemic enrollment projections and 30 of 31 states anticipate that enrollment growth in FY 2021 will outpace the current fiscal year.

States attribute higher enrollment projections in FY 2020 and FY 2021 to the worsening economy and the effects of the MOE. The effects of the economy in recent months and expectations that these conditions will get worse were major factors in state enrollment projections. In addition, states reported that the MOE was also a factor. MOE requirements eliminate the usual enrollment churn that occurs when some individuals lose eligibility and are dis-enrolled from Medicaid each month. However, even when states can resume eligibility redeterminations, given the magnitude of the economic crisis, many individuals are likely to retain eligibility because their income will continue to fall below Medicaid income eligibility thresholds. In the past, some eligibility churn was attributable to individuals losing coverage due to barriers maintaining coverage at renewal or when states conducted periodic data matches between renewals. Prior to the pandemic, these types of barriers were potentially depressing enrollment for some individuals who remained eligible. Beyond the conditions to access the enhanced funding, some states are implementing actions to expand eligibility and make it easier to apply such as allowing for self-attestation of eligibility criteria, eliminating premiums, expanding the use of presumptive eligibility, or otherwise simplifying application processes.

Spending Trends

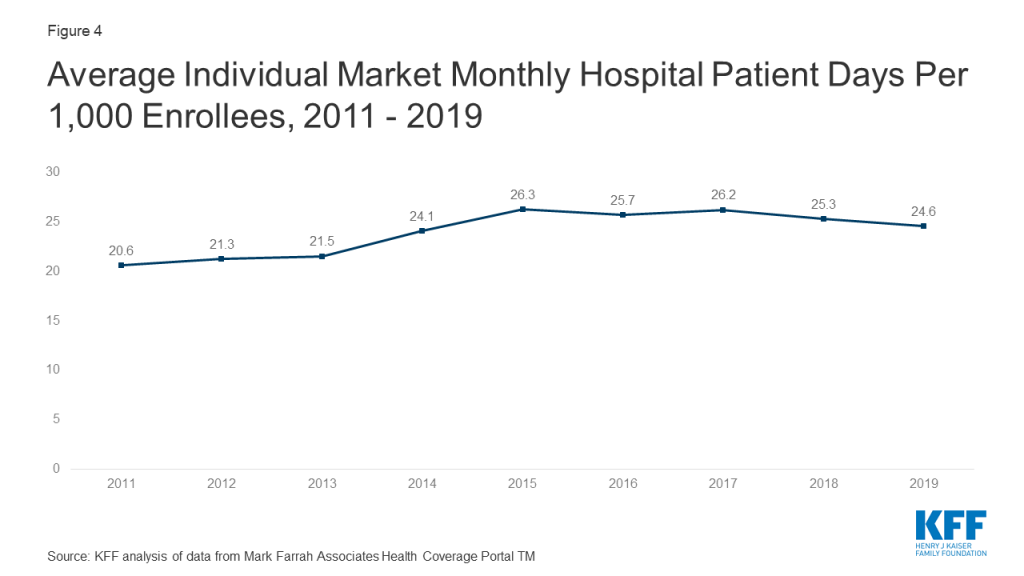

Over half of states with projections anticipate that FY 2020 spending growth will be higher than spending growth projections made prior to the pandemic. Similar to other health care payers, the spending picture for Medicaid for the remainder of FY 2020 is somewhat mixed. Over half of states with projections (18 of 32) expect FY 2020 total Medicaid spending to exceed pre-pandemic projections while eight states anticipate no material change. The remaining six states expect somewhat lower spending in FY 2020 due to public health emergency restrictions halting non-urgent services and otherwise resulting in lower utilization of health care services. Some states with managed care noted that without adjustments in capitation rates, reductions in utilization will not reduce overall costs while increases in enrollment will continue to drive expenditures up. Without available claims data to review, many states could not anticipate how lower costs attributable to lower utilization would compare to costs related to increased enrollment and new/unanticipated expenditures related to COVID testing and treatment.

States also reported policy actions to expand access to services and increase payment rates for selected providers. Some states pointed to actions that could put upward pressure on spending and potentially offset expenditure reductions due to decreased utilization. Such actions include waiving copayments and prior authorization requirements, allowing early pharmacy refills, expanded telehealth services and reimbursement rates, and increasing provider rates particularly for hospitals, nursing facilities, and other long-term services providers. Examples of reimbursement adjustments include bumps for COVID-positive nursing facility residents or a hospital DRG add-on of 20 percent for COVID-19 positive enrollees.

For FY 2021, nearly all states with projections (29 of 30) anticipate that total Medicaid spending rates will continue to increase over FY 2020 spending rates, primarily due to increases in enrollment. In addition, states anticipate upticks in utilization for new enrollees and previously enrolled individuals (catch-up for depressed utilization in FY 2020) and pressure to address provider reimbursement issues will contribute to expenditure growth in FY 2021. A few states also pointed to the expected continuation of telehealth expenditures. While not asked about projections beyond FY 2021, at least one state commented that economic impacts and higher enrollment growth will likely continue beyond FY 2021.

Expected Budget Shortfall

Four in ten states with projections (13 of 33) reported currently projecting a Medicaid budget shortfall for FY 2020. A few states said that the combination of a supplemental appropriation and the additional federal support from the FMAP increase will help to address potential Medicaid budget shortfalls in FY 2020. However, a number of states reported that FY 2020 budgets were still in flux and broader reductions in overall state revenues may require reductions in Medicaid and other state programs. At least one state reported administrative reductions like hiring freezes and deferment of non-essential contracts.

Among the states with projections available, nearly all reported a budget shortfall is “almost certain” or “likely” for FY 2021 (17 of 19 states). Two other states reported a “50-50” chance of a Medicaid budget shortfall for FY 2021. No states reported that that a FY 2021 budget shortfall was “not likely” or “almost certain no shortfall.”

Looking Ahead

The FFCRA temporary FMAP increase has already provided fiscal relief to states facing mounting budget pressures from the pandemic. Enhancing that relief by further increasing the temporary FMAP rate and extending its duration could provide greater fiscal stability to states and support the costs of growing increases in enrollment as the economy worsens, at increased federal cost. Multiple state groups including the National Governors Association and the National Association of State Medicaid Directors have called for a further increase in the FMAP. The House bill introduced on May 12, 2020 would increase the FMAP by 14 percentage points from July 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021. Without certainty of additional federal support, many states will need to develop balanced budgets for the fiscal year beginning on July 1 (for most states) that could likely include significant spending cuts, including for Medicaid programs, at a time when demand for services is growing. We will continue to track state changes to Medicaid in response to the pandemic and will be fielding a more detailed survey of Medicaid programs this summer to capture assumptions about Medicaid spending and enrollment as well as policy changes that were included in state fiscal year (FY) 2021 budgets.