Gaps in the Emergency Paid Sick Leave Law for Health Care Workers

Background

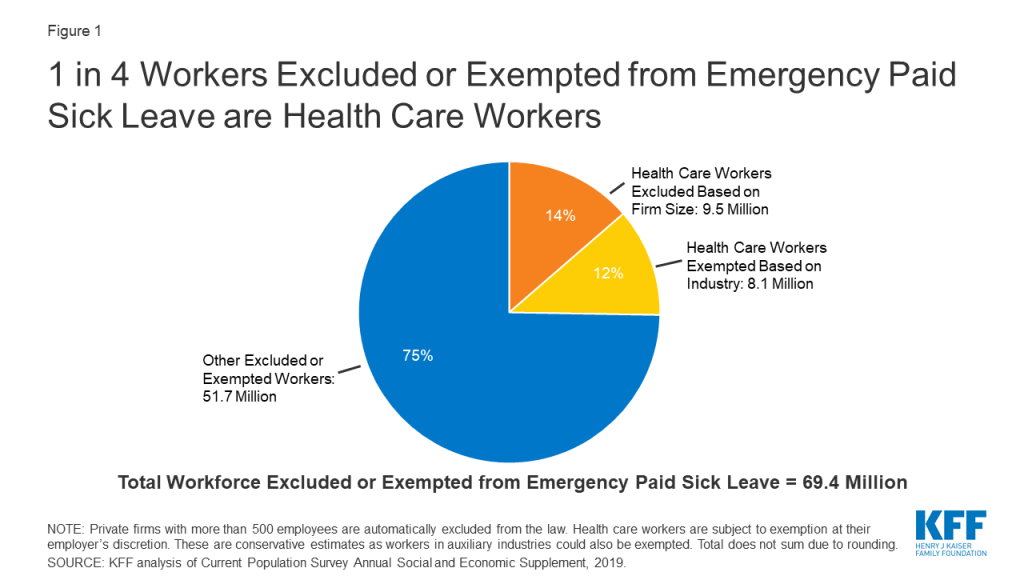

The emergency paid sick leave benefit that took effect in April as part of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) guarantees eligible workers up to 80 hours of paid leave for a health issue arising from coronavirus. The Act represents the country’s first federal law aimed at providing workers paid leave, though it is set to expire at the end of 2020. In order to reduce the spread of coronavirus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended that employers actively encourage employees who are exhibiting symptoms to stay home and maintain physical distancing. The new law temporarily provides short-term paid sick leave to as many as 86.3 million workers1 , according to our analysis of the Census Bureau’s 2019 Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). However, the emergency paid sick leave provisions leave out a large swath of American workers by excluding those at private businesses with 500 or more employees, and offering broad exemptions for employers of emergency responders and health care workers, regardless of firm size. While most health care employers offer paid sick leave to their workers, that leave usually requires accrual and may not be available to all workers or for as long as the emergency leave in the FFCRA.

While the legislation did not specify who would be classified as a health care worker, the Department of Labor (DOL) subsequently issued guidelines that permit many health care providers as well as a wide range of health-related entities to exempt their workers. Organizations responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as hospitals, doctors’ offices, clinics, residential facilities, medical schools, laboratories, pharmacies, and even contractors that provide services to these institutions, can be exempted. Should they choose the exemption, these employers are not required to offer emergency paid sick leave to either employees who provide direct patient care or who provide health-related services but do not have direct exposure to patients, such as janitors and food service workers.

In response to the gaps in emergency paid leave protections for health care and emergency response workers, the New York Attorney General has filed a lawsuit against the Trump Administration2 and several organizations have called on the Department of Labor to reconsider its expansive definitions of workers who may be exempted. Additionally, since the beginning of the pandemic, five states and 14 localities, plus Washington, DC, have enacted new emergency paid sick leave laws or expanded existing ones3 . On May 15, 2020, the House of Representatives passed the HEROES Act, legislation that would remove the federal FFCRA’s exclusion for private employers with 500 or more employees and the exemption for health care and emergency response workers, among several other coronavirus-related provisions. The bill is currently stalled in the Senate.

How Many Health Care Workers Do Not Have Access to the Coronavirus Emergency Paid Sick Leave?

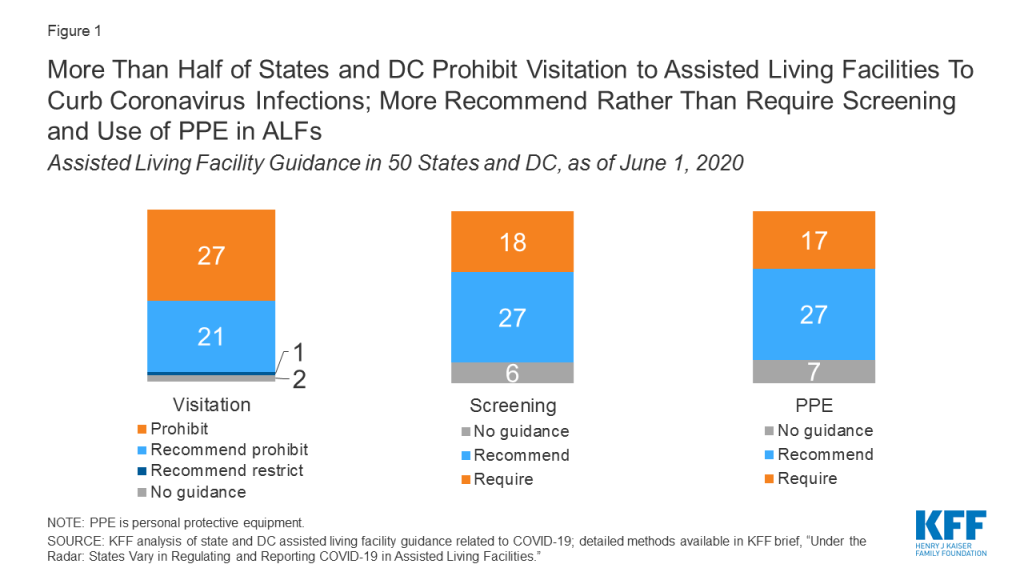

Based on analysis of the 2019 CPS ASEC, we estimate that at least 69.4 million workers, or approximately four in ten workers, are potentially ineligible for emergency paid sick leave benefits. Approximately one in four (25%) of those workers works in the health care industry (Figure 1). In particular, the law automatically excludes the 9.5 million health care workers that work for a private employer with 500 or more employees (6% of the American workforce). An additional 8.1 million health care workers are subject to exemption (5% of the workforce) at their employer’s discretion. Taken together, as many as 17.7 million health care workers are not guaranteed access to emergency paid sick leave benefits under this law.

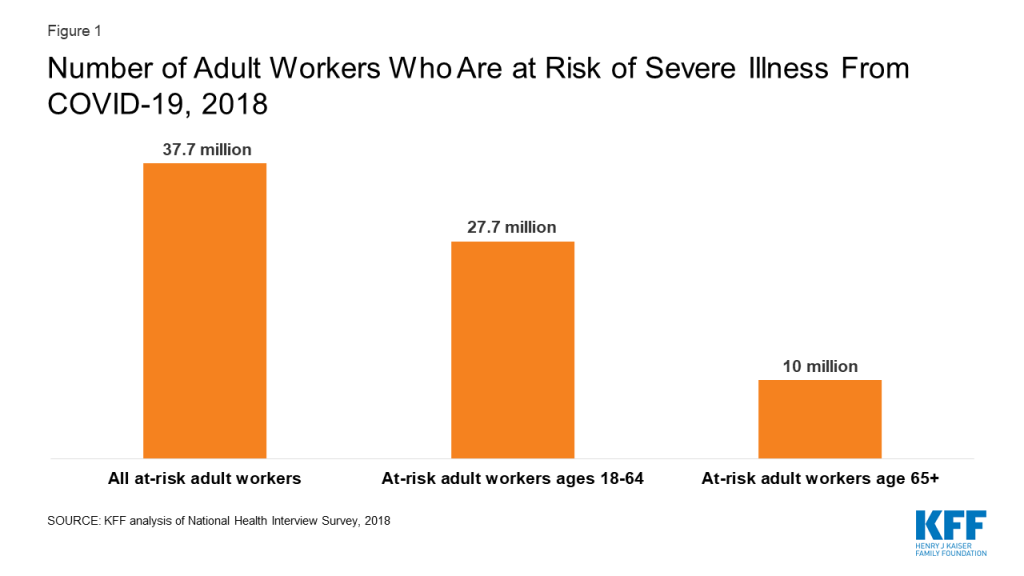

The CDC estimated in late May that more than 63,000 health care personnel had contracted COVID-19. Those working in the health care industry are of particular interest because of their increased risk of contracting the virus from infected patients as well as their potential to transmit the virus to patients at high risk of becoming seriously ill. While it is not known how many employers have elected not to offer emergency paid sick leave benefits under the exemption, we estimated the number of workers in the health care industries most likely to be excluded based on the DOL’s exemption criteria (see the Methodology section). This is a conservative estimate, as it does not include workers in some auxiliary services, such as industries that provide services necessary for the maintenance and operation of health care facilities and that can be exempted under the DOL’s guidance.

While most health care and social assistance firms offer paid sick leave as an employee benefit, whether voluntarily or state/locality-mandated, 15% of workers in these industries do not have any paid sick leave. Moreover, employer paid sick leave programs typically require accrual of time off and offer an average of 7 to 8 days of sick leave, which is fewer than the number of days recommended by the CDC for recovery and quarantine from COVID-19 for health care workers. By contrast, the FFCRA’s emergency paid sick leave law provides 2 weeks of paid sick leave, immediately available to all eligible workers, rendering it particularly valuable during this pandemic. Lack of comprehensive paid sick leave may discourage workers who have symptoms of coronavirus from staying home, potentially exposing their patients and co-workers to the virus.

Who are the Exempted and Excluded Health Care Workers?

Women make up the majority (75%) of the 17.7 million workers in the health care industry who are either automatically excluded from the new emergency paid sick leave law or subject to exemption (Figure 2). Nearly 4 in ten (39%) of them are people of color. Data suggest that due to higher rates of underlying health conditions, communities of color are at increased risk of serious illness if they contract COVID-19 and they face increased challenges related to health care access and social and economic factors. Other data find that communities of color are also experiencing higher rates of death from COVID-19. Additionally, about a quarter (24%) of the health care workforce excluded or subject to exemption are part-time workers, many of whom are less likely to receive any other type of paid leave benefit from their employer, as these benefits are often only available to full-time workers. Moreover, 18% are low-wage4 , for whom having to take unpaid leave when they are sick could put them in a difficult financial situation. Other research finds that lower-wage workers are also less likely to have access to other paid sick leave than higher-wage workers. For example, in 2019, only 47% of lower-income workers in private industry had access to paid sick leave, compared to 90% of higher-wage workers.

Many workers in the health care industry work in a setting where they may have exposure to patients and other health care workers (Table 1). More than four in ten (42%) work in hospitals, about a quarter (24%) work in long-term care facilities, which have been disproportionately affected by outbreaks of COVID-19, and about one in five (19%) work in physician offices and other outpatient care centers. Another 15% work outside of patient care settings, such as for the pharmaceutical industry, other medical supply companies, and a variety of other related health services.

| Table 1: Worksites of the 17.7 Million Health Care Workers Who May Not Qualify for Emergency Paid Sick Leave | |

| Hospitals | 42% |

| Home, nursing, and residential care | 24% |

| Home health care services | 9 |

| Nursing care facilities | 9 |

| Residential care facilities, without nursing | 6 |

| Physician offices and outpatient care | 19% |

| Offices of physicians | 9 |

| Outpatient care centers | 11 |

| Medical and pharmaceutical manufacturing | 7% |

| Pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing | 3 |

| Medical equipment and supplies manufacturing | 4 |

| Other health care services | 8% |

| SOURCE: KFF analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2019. | |

Discussion

Health care workers who continue to work while sick because they cannot afford to stay home without pay may face difficult tradeoffs between the need for an income and concerns about exposing patients or their colleagues. The FFCRA’s emergency paid sick leave provides an economic cushion that could allow health care workers to stay home when they are ill and help curb the spread of the pandemic. However, gaps in the law leave many workers without access, including 17.7 million health care workers. Health care workers without access to other types of paid leave may find it even more difficult to take time off work. Lack of paid sick leave could result in workers being forced to choose between going to work while they have symptoms and staying home without pay. Media reports have indicated that some health care workers are feeling the impact of the lack of access to emergency paid sick leave, with some worrying how they will pay their bills if they get sick with coronavirus and need to take time off work to recover.

New York’s lawsuit argues that the Department of Labor unlawfully allows for exemption of health care and emergency response workers. Additionally, the HEROES Act, passed by the House of Representatives in May 2020, attempts to close many of the gaps in access to emergency paid sick leave by extending the requirement to private firms with 500 or more employees and by removing the exemption for health care providers and emergency responders. These changes, if implemented, may make it easier for sick workers to stay home without losing pay and may help protect the others from exposure to COVID-19.

Methodology

This analysis is based on KFF analysis of the 2019 Community Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement. We include self-employed workers, which make up about 9% of the workforce, and workers in the private sector, state and local governments, and the federal government. We define the health care and emergency response workforce as all individuals who earned at least $1,000 during the past year and indicated that their job was in one of the Census codes listed in Table 2. Excluded workers are those who work for a private firm with 500 or more employees and exempted workers are those who work in the health care or emergency response industries. Looking at industry rather than occupation allows for analysis that more closely resembles the broad exemptions as defined by the DOL, though this list does not include auxiliary industries necessary for the operation and maintenance of health care and emergency response entities, which may also be exempted. We did not include the offices of dentists, chiropractors, optometrists, or ‘other’ health practitioners, which employ an additional 1.4 million workers.

| Table 2: Industry Classification Codes | |

| Health Care | |

| Census Code | Description |

| 2190 | Pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing |

| 3960 | Medical equipment and supplies manufacturing |

| 7970 | Offices of physicians |

| 8090 | Outpatient care centers |

| 8170 | Home health care services |

| 8180 | Other health care services |

| 8190 | Hospitals |

| 8270 | Nursing care facilities |

| 8290 | Residential care facilities, without nursing |

| Emergency Response | |

| 8370 | Individual and family services |

| 8380 | Community food and housing, and emergency services |

| 9470 | Justice, public order, and safety activities |

| SOURCE: Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2019. Codebook Appendix A. | |

- Our estimates are based on 2019 employment data. In May 2019, 6 million people were unemployed. In May 2020, 21 million people were unemployed. ↩︎

- In August 2020, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of N.Y. ruled in favor of New York and in September 2020, the DOL amended the regulation to more narrowly define ‘health care worker.’ ↩︎

- CA, CO, NY, OR, and WA. In CA: Long Beach, Los Angeles City and Co., Oakland, Sacramento City and County, San Francisco, San Jose, and Santa Rosa. San Mateo and Sonoma Counties have temporary emergency paid sick leave laws that are not included here because they only apply to certain employers in unincorporated parts of the county. In other states: Goshen, IN, Wilmington, NC, Philadelphia, PA, Burlington, VA, and Seattle, WA. Source: KFF analysis of A Better Balance Emergency Paid Sick Leave Tracker. Updated Oct. 2020. ↩︎

- Low-wage refers to workers in the bottom 25% of earners, or less than $22,000 annually. ↩︎