States Are Getting Ready to Distribute COVID-19 Vaccines. What Do Their Plans Tell Us So Far?

Issue Brief

Introduction

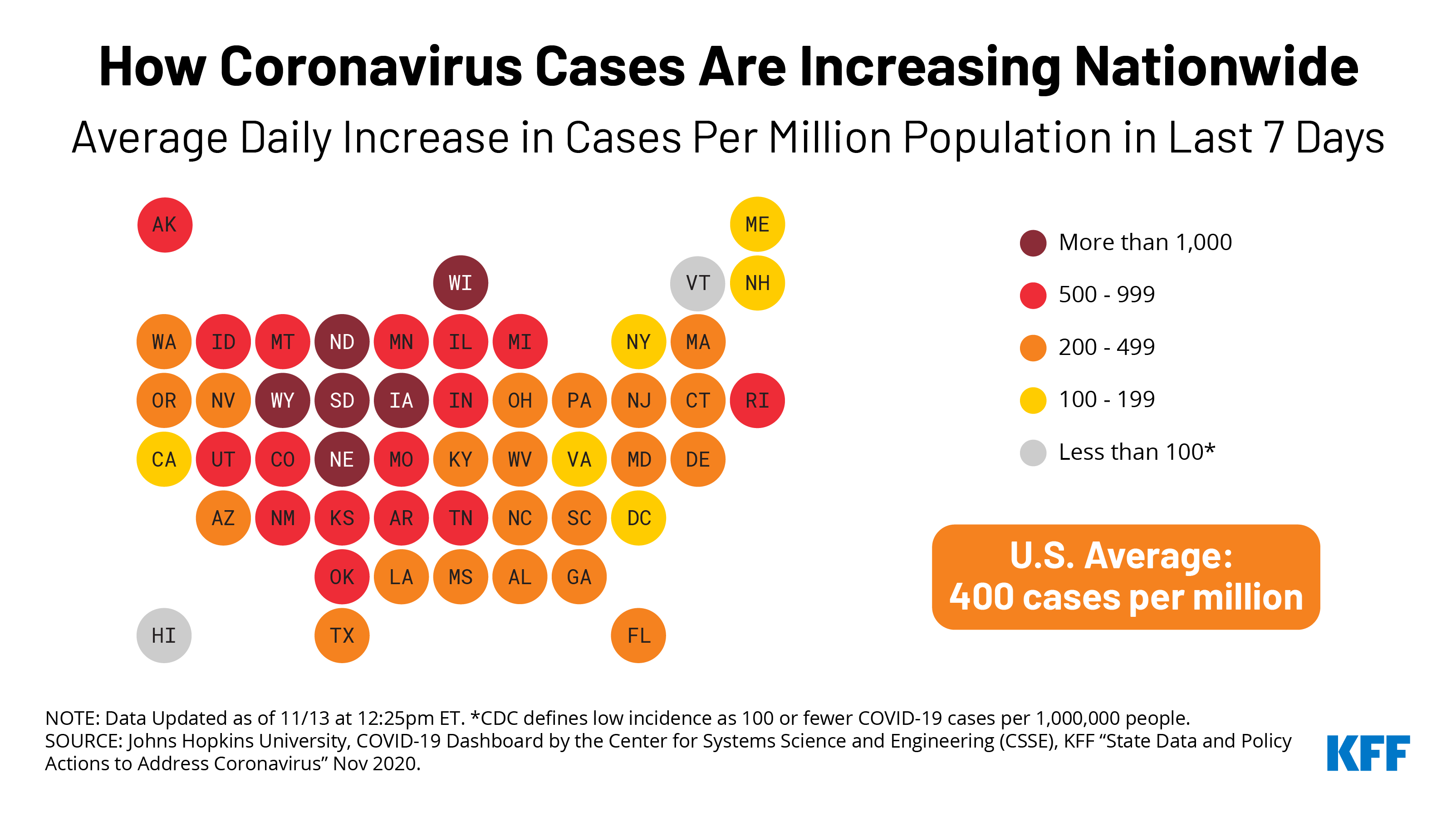

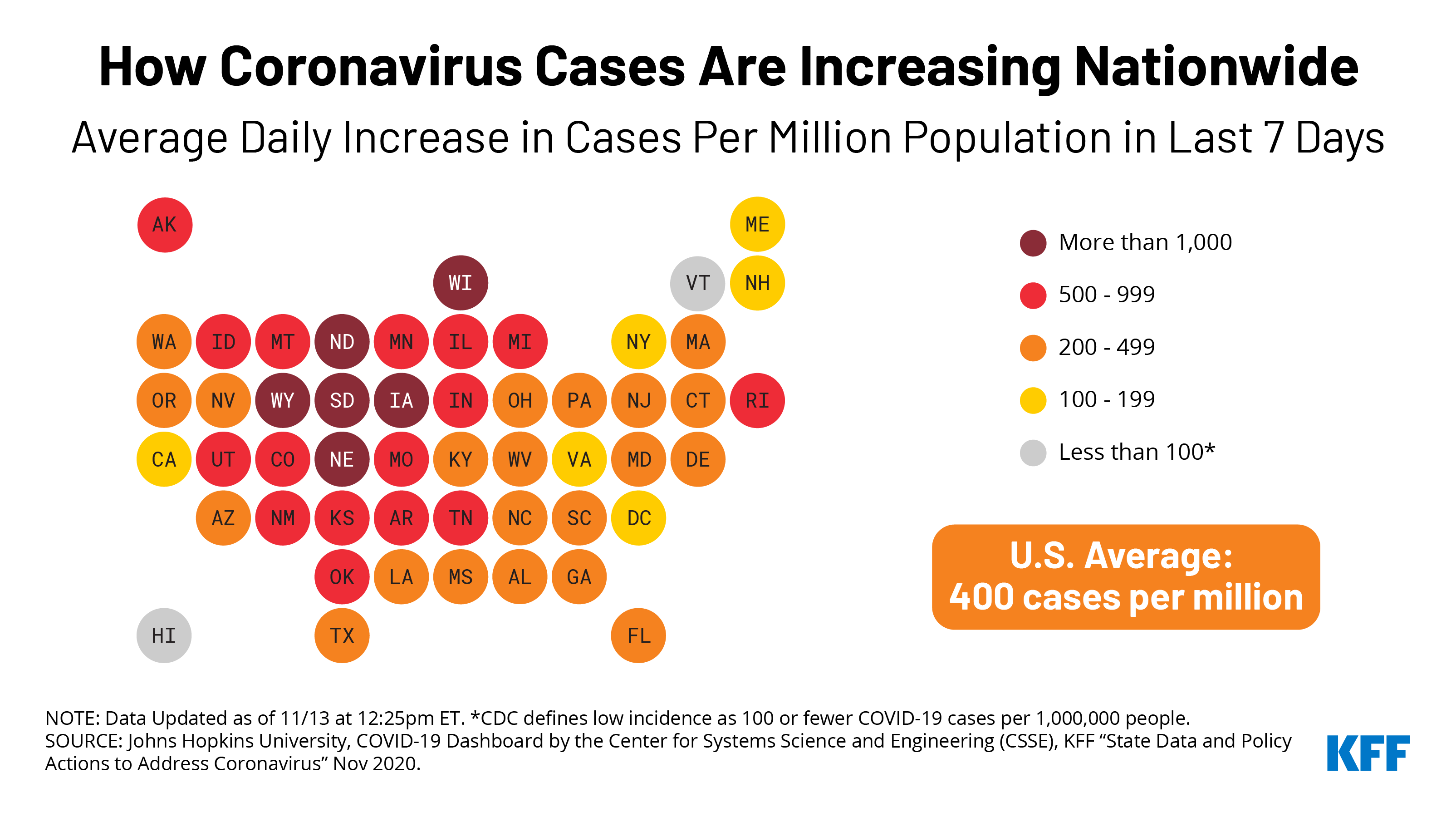

With the U.S. still in the midst of an escalating COVID-19 pandemic, attention to the race for a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine has intensified. What is clear is that when vaccines do become available, ensuring equitable and rapid distribution to the U.S. population will present an unprecedented challenge. The Trump Administration, under Operation Warp Speed, has already purchased in advance hundreds of million doses of several vaccine candidates, two of which have already demonstrated significant efficacy in Phase 3 clinical trials, and has begun planning for what will be the largest scale vaccination distribution effort ever undertaken in the U.S. This task will soon be inherited by the incoming Biden Administration, which has established a COVID-19 Task Force and is already planning its response.

A limited number of COVID-19 vaccine doses may start to become available as early as December, with more doses available over time. State, territorial, and local governments, who already have primary authority over routine vaccination, will play an increasingly important role in the distribution of these vaccines as more doses become available. In preparation, the federal government has asked the 64 jurisdictional immunization programs (all 50 states and DC, 8 U.S. territories and freely associated Pacific states and five cities) that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funds and works with to develop COVID-19 vaccine distribution plans based on an Interim Playbook. The Playbook includes planning assumptions for jurisdictions to follow and requested information in 15 key areas (see Box). First drafts of these plans were due by October 16.

CDC Interim Playbook Planning Assumptions and Key Areas of Information Requested from States for Vaccine Distribution Planning

In its Interim Playbook CDC provided states with a set of planning assumptions as they developed their vaccine distribution plans. For example, CDC outlined how vaccine distribution will likely proceed in phases:

- Phase 1 – there is an initial limited supply of vaccine doses that will be prioritized for certain groups and distribution more tightly controlled and limited number of providers administering the vaccine;

- Phase 2 – supply would increase and access expand to include a broader set of the population, with more providers involved, and;

- Phase 3 – there would likely be sufficient supply to meet demand and distribution would be integrated into routine vaccination programs.

CDC requested each state outline its capacities for distributing COVID-19 vaccines across a broad set of 15 critical areas: public health preparedness planning; organizational structure; plans for a phased approach; identifying and reaching critical populations to be prioritized for vaccine access; identifying and recruiting providers to administer the vaccine; vaccine administration capacity; allocating, distributing, and managing its inventory of vaccines; storage and handling; collecting, tracking, and reporting key measures of progress; second dose reminders; immunization information system requirements; developing a comprehensive communications plan around vaccination; regulatory considerations; safety monitoring; and program monitoring.

CDC guidance and federal oversight could evolve over the next several months as vaccines become available and distribution begins. The Biden campaign and transition team have planned for a more prominent role for the federal government in the U.S. COVID-19 response, which would likely include more detailed federal guidance and a stronger federal hand in vaccine distribution, planning and implementation, even as state and local jurisdictions will remain responsible for much of this effort. A critical challenge facing vaccine distribution efforts will be funding. To date, only $200 million has been distributed to state, territorial, and local jurisdictions for vaccine preparedness, though it is estimated that at least $6-8 billion is needed. President-elect Biden has said his administration would seek to invest $25 billion in manufacturing and distribution, which would require Congressional action.

While the CDC has made executive summaries of these plans available, there is no central repository for the full plans. We therefore sought to collect plans available from all 50 states and DC, as of November 13, identifying 47 full state plans in total (linked in the “State Plans” tab). We then reviewed each plan to gauge how states described their vaccine distribution planning progress to date. Rather than assess every single component of these plans in detail we identified common themes and concerns across the state plans, in particular focusing on what states reported regarding their progress in the following key areas:

- identifying priority populations for vaccination in their state;

- identifying the network of providers in their state that will be responsible for administering vaccines;

- developing the data collection and reporting systems needed to track vaccine distribution progress; and

- laying out a communications strategy for the period before and during vaccination.

Where are States in their Planning?

Based on the information in their plans, states are in varying stages of preparation for distributing a COVID-19 vaccine. While all have established a task force or planning committee to steer these efforts, which include representatives from different sectors, some have been planning for several months while other states’ planning efforts have started more recently. Some states have already begun the process of signing up providers to administer COVID-19 vaccines and building out existing immunization registries, while others are still just developing plans to do the same. All reported, however, that these initial plans are to be considered drafts only, to be updated as more information from the federal government and about a vaccine itself was available. Specifically, almost all cited the need to know which vaccine(s) would be authorized or approved, and that they will look to further federal guidance and recommendations before some key decisions are made, such as finalizing which individuals will be targeted as priority populations. Several raised concerns about the lack of visibility regarding vaccine distributions that will be made directly from the federal government to certain providers in their states, such as large pharmacy chains. These concerns were raised before the November 12 announcement by the federal government that it will be distributing future COVID-19 vaccines directly to some independent pharmacies and multi-state pharmacy chains across the U.S., in parallel to state efforts to recruit vaccination providers. States also discussed lessons learned from previous vaccine distribution efforts such as H1N1 pandemic influenza, including the need to build flexibility into distribution plans when supply is unpredictable and tailoring messages and outreach to diverse populations, which are certain to be challenges for a COVID-19 vaccine as well. Finally, even recognizing the that states are in different states of readiness in terms of their distribution planning efforts, it is clear all state health departments are taking this responsibility seriously and are overseeing significant efforts to make progress in their preparations.

Priority Populations1

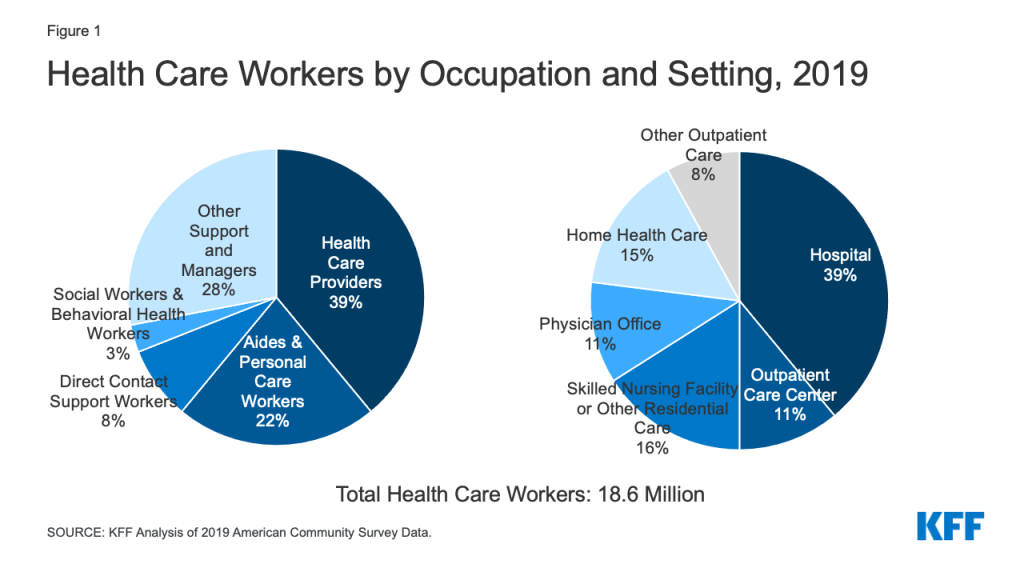

Each state will have to determine exactly who will be first in line to receive the likely limited number of vaccine doses that will be made available initially. In their plans, almost every state reports they are relying heavily on guidance from the federal government to define who these priority populations are, drawing on recommendations from the National Academies of Medicine and also expecting additional guidance from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Many states report they will shape their prioritization plans using locally-defined criteria as well. Every state plan highlights the following broad categories as being priority populations for Phase 1 efforts: health care workers, essential workers, and those at high risk (older people and those with pre-disposing health risk factors). Most plans recognize (and CDC indicated in its guidance) that there will likely not be enough vaccines at first for all individuals identified in these Phase 1 priority groups. Even so, plans show that some states are much further along in defining prioritization categories and enumerating the number of people that fall into those categories. For example:

- Less than half (19 of 47, or 40%) of state plans reviewed include a numerical estimate of the number of individuals in different priority populations; the majority of states report they are still developing their data sources and methodology to calculate the number in their priority groups.

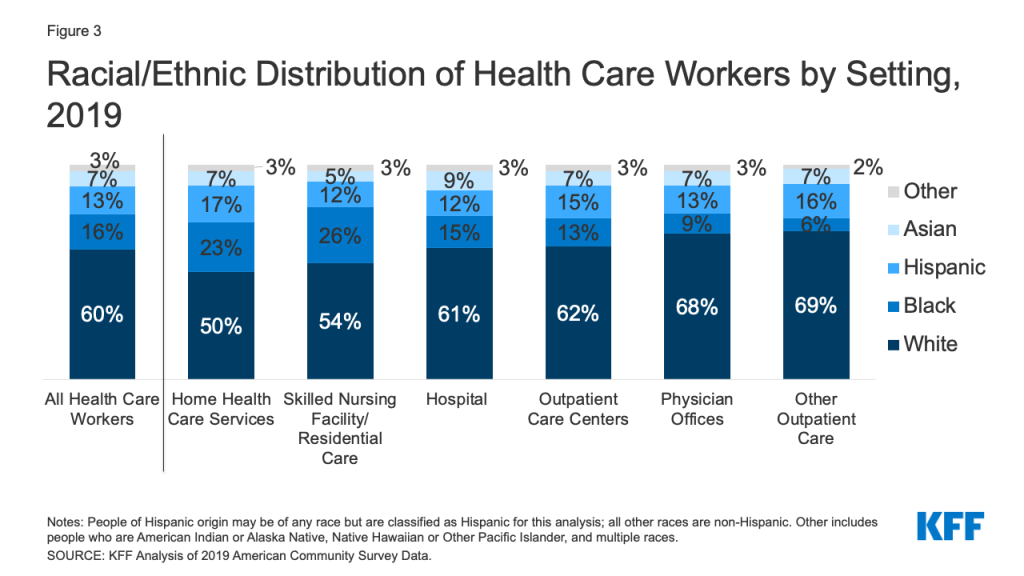

- Some states report already developing specific estimates of the numbers of health care workers likely among the first individuals targeted for vaccination, while other states do not include these estimates, or mention that they are working on developing methods to identify the numbers to be targeted in this group.

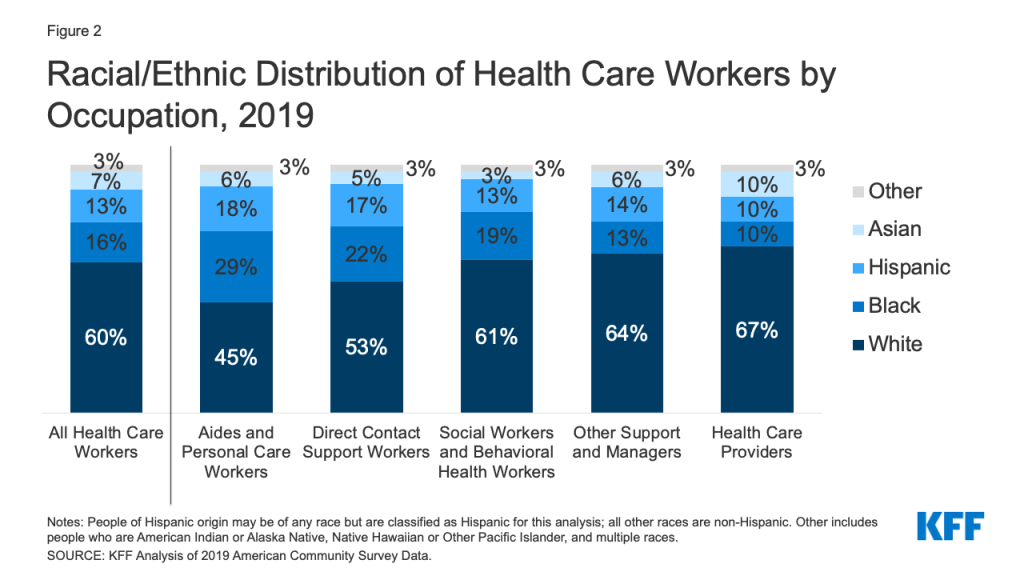

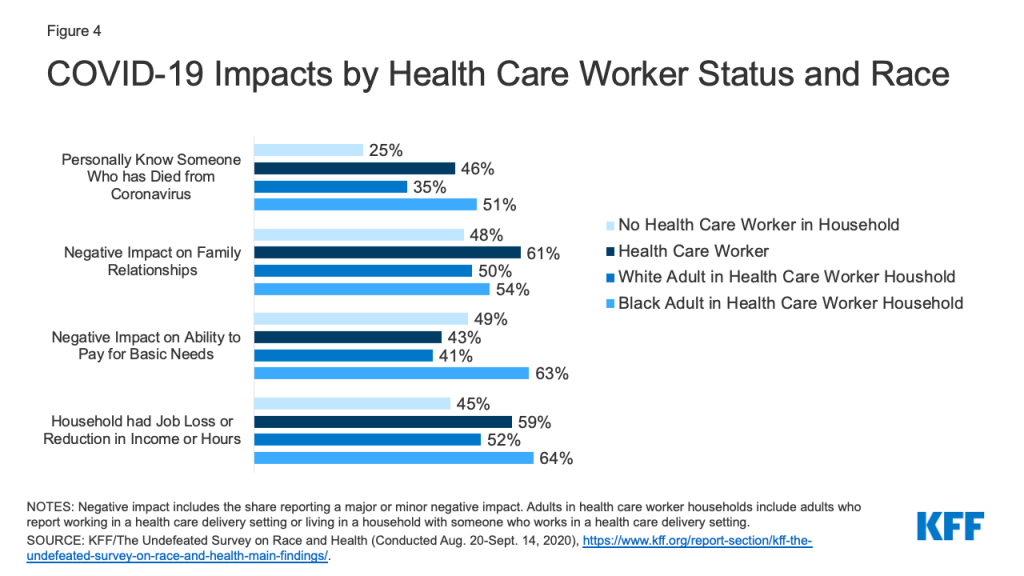

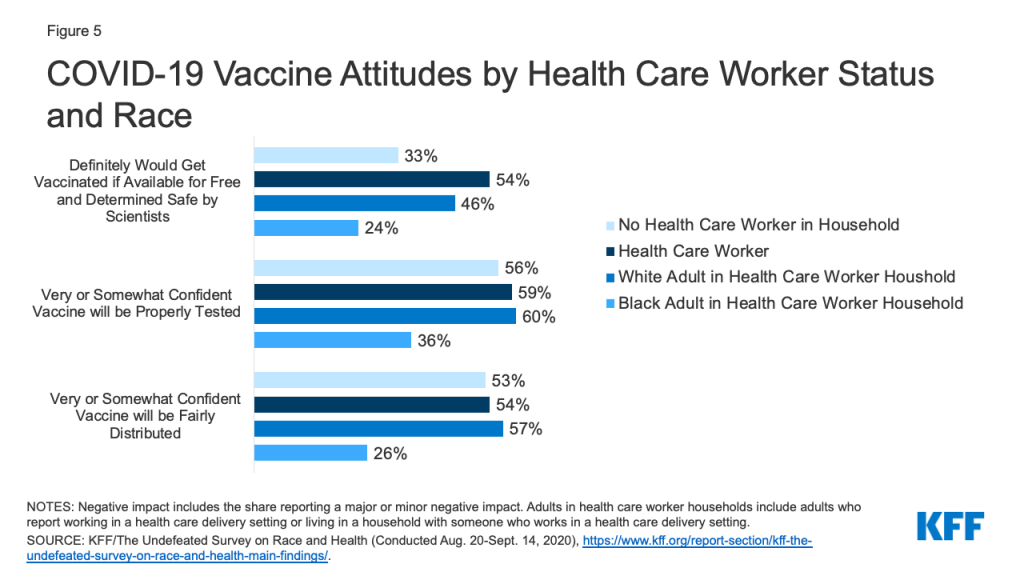

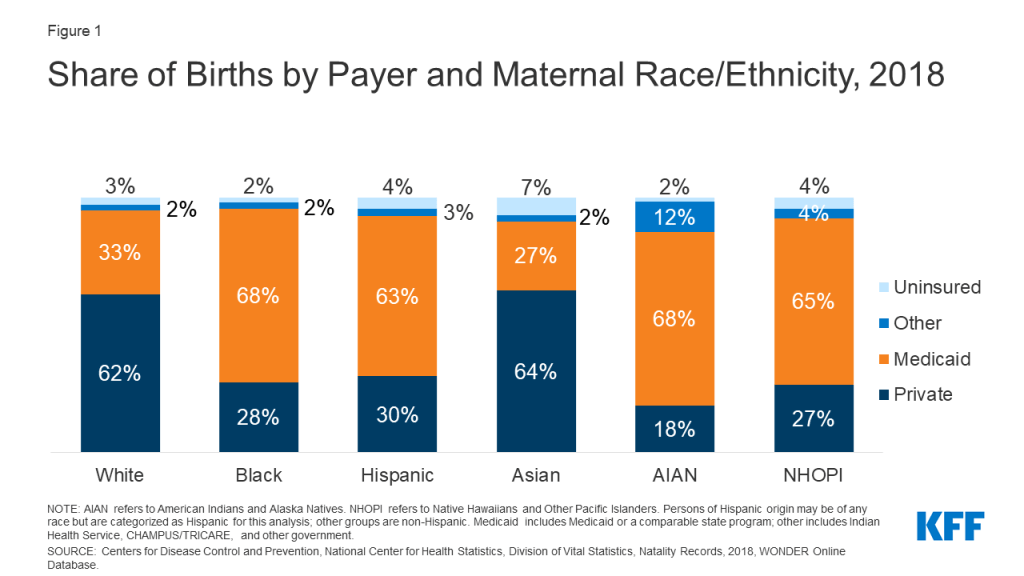

- A majority of states (25 of 47, or 53%) have at least one mention of incorporating racial and/or ethnic minorities or health equity considerations in their targeting of priority populations. Some states expect to make racial and ethnic minorities an explicit priority population group, while others report using more general or indirect methods to do so, such as through use of the social vulnerability index (as was recommended by the NAM) and/or a Health Equity Team or Framework, as in the case of Arizona, California, Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, Ohio, and Vermont.

Providers

Each state will rely on a network of providers to administer the vaccines to individuals. These providers will likely include hospitals and doctors’ offices, pharmacies, health departments, federally qualified health centers, and other clinics that play a role in administering vaccines today. However, given the need to quickly vaccinate most residents, states will need to include additional partners, such as long-term care facilities, in the network and will potentially establish mass vaccination sites in public locations like schools and community centers. Prior to distribution and administration of vaccines, states will have to identify, vet, and approve hundreds to thousands of partners and site locations for vaccine delivery. According to the draft plans, states are at different points in the process of identifying these providers and expanding their network of providers needed to deliver vaccines to priority population groups. States that require providers to participate in immunization registries or those that already have most providers participating in these registries are further along in developing their provider networks, while other states report that they still need to start the process of enrolling providers.

- Less than a third (13 of 47, or 28%) of states’ plans provide an estimate of the number of vaccine providers in the state, and only six provide some estimate of the number of providers by type (though some of these are limited to only one provider type).

- About half (24 of 47, or 51%) report an estimate of the number of providers already participating in their immunization registries. A few states have also begun specific outreach to register as COVID-19 providers, although these efforts are in their beginning phases. At the same time, some states, particularly rural states, raise concerns about the lack of personnel to carry out vaccination in some areas, or how they will be able to send small enough batches of vaccines to be distributed by rural providers who may only be vaccinating a limited number of individuals.

- Only a subset (12 of 47, or 26%) of state plans specifically mention or consider providers that are needed to reach racial and ethnic minorities.

- Across plans, the most common types of providers that states report still needing to reach out to or incorporate as COVID-19 vaccine providers include: tribal providers, long-term care facilities, correctional facilities, and other types of adult care providers.

Data Collection and Reporting

All states have an immunization registry of one kind or another to track vaccinations administered by providers in their state. These registries range in terms of their comprehensiveness and reporting functionality. To incorporate the data collection and reporting needs for COVID-19 vaccination, many states are relying on (and often expanding) existing state-level immunization registries, while other states are developing new systems or using systems provided by the federal government. From the information in the draft plans, it is clear that some states are in a much better position in terms of their data collection and reporting capacity for COVID-19 vaccines, while others have more work to do to develop their systems, In addition, some common issues have been raised by states in their plans.

- Just over half (25 of 47, or 53% ) of state plans report having immunization registries/database systems in place that are described as being (at least fairly) comprehensive and reliable; in the other state plans that information is unclear. Most states report still having to develop or add functionality to their existing immunization registries to be prepared for COVID-19 vaccine administration.

- Most states report they will have no issues reporting the key data from their immunization registries to federal systems, though at least fifteen states report that data sharing agreements with federal partners are still being reviewed or remain in process.

- Several states raise concerns about the ability to report certain CDC-recommended data elements to federal systems or meet CDC time requirements for reporting. States also mention limitations in collecting race/ethnicity data on individuals vaccinated.

- Virtually all states’ plans incorporate expectations and procedures to report any vaccine adverse events through federal reporting systems such as the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS).

Communications

Developing a communications plan before and during COVID-19 vaccination will be critical component of state planning. CDC requested that states outline how they will proactively design communication plans that anticipate and respond to the needs and concerns of different population groups. This includes the need to address misinformation and vaccine hesitancy, as well as crisis communications. Some states’ plans have very detailed explanations of their approach to communications across the vaccination phases, while others provide very little detail. Additionally, some state plans recognize the need to develop targeted messaging for vulnerable populations, while others do not.

- About half (23 of 47, or 49%) of plans specifically mention racial/ethnic minorities or vulnerable populations when discussing COVID-19 vaccine communication.

- Just over a third (18 of 47, or 38%) of state plans include at least a mention of addressing vaccine misinformation but most of these states do not provide specific strategies for countering misinformation.

State Plans

Links to State Plans

Endnotes

- While jurisdictions were asked to reach out to tribal nations within their respective areas for involvement in planning efforts, tribal nations have sovereign authority to provide for the health and welfare of their populations. This authority includes decisions around access to and distribution of the vaccine as well as establishing priority groups to receive the vaccine. We did not review state plans to assess their reported coordination efforts with tribal nations, including for outreach to tribal populations. ↩︎