What is at Stake for Health and Health Care Disparities under ACA Repeal?

Issue Brief

Key Takeaways

Health and health care disparities, which are differences between groups in their health status and their ability to obtain care, remain a persistent issue in the United States. This brief describes health and health care disparities today, highlights recent advancements in reducing disparities under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and discusses how the American Health Care Act (AHCA) and proposed reductions in discretionary funding may affect ongoing efforts to address disparities.

- There have been recent advancements in reducing disparities that reflect provisions under the ACA. People of color and low-income individuals face significant disparities in access to and use of care as well as health outcomes. ACA investments through discretionary programs to strengthen public health and prevention and the health care workforce and delivery system supported reduction of disparities. In addition, the Medicaid and Marketplace coverage expansions led to large gains in health insurance for low-income individuals and people of color, narrowing longstanding disparities in coverage.

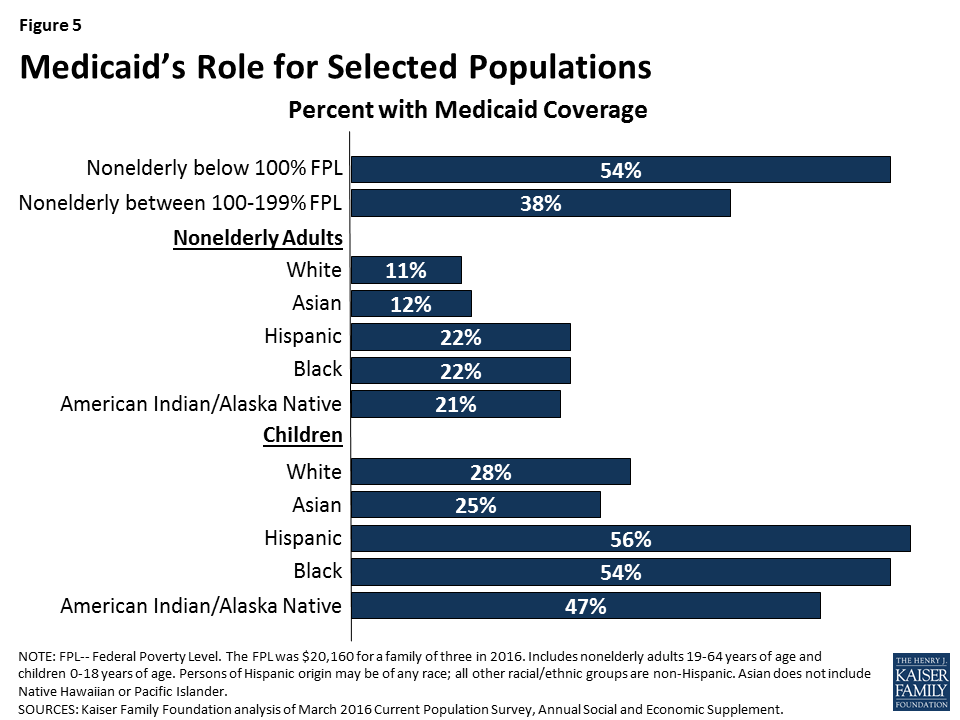

- The proposed changes to Medicaid under AHCA would disproportionately affect low-income individuals and people of color for whom the program is a central source of coverage. Medicaid covers over half of all poor families, one in five adults of color, and over half of children of color. The changes proposed in AHCA, including the cap on federal Medicaid financing and elimination of enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion, would likely lead to large coverage losses among these groups as would the proposed changes to tax credits for private coverage.

- Other reductions in discretionary health spending may also reduce availability of services, limit progress expanding the health care workforce, and constrain continued research to understand and address disparities. Specifically, AHCA would eliminate funding for the Prevention and Public Health Fund, and the President’s 2018 budget proposes a 17.9% cut to discretionary funding for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Introduction

Many groups, including low-income individuals and people of color, face disparities in their ability to obtain needed care and in their health outcomes. There have been recent advancements in reducing disparities under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The American Health Care Act (AHCA) proposal to repeal and replace the ACA and cuts to discretionary spending, as proposed in the President’s 2018 budget, could erode recent progress and negatively affect disparities. This brief describes health and health care disparities today, highlights recent advancements in reducing disparities under the ACA, and discusses how changes proposed in the AHCA and cuts to discretionary funding could affect ongoing efforts address disparities.

Health and Health Care Disparities Today

Health and health care disparities are differences between groups in their health status and ability obtain medical care that are rooted in historic economic, social, and racial disadvantages. Although disparities have been documented for decades and there have been overall improvements in our nation’s health, many disparities have persisted and, in some cases, widened over time.1 Addressing disparities is not only important from a social justice standpoint, but also for improving our nation’s health and reducing unnecessary costs.2 With projections estimating that people of color will make up more than half of the population by 2044, it is increasingly important to address disparities.3

Today, many groups face significant disparities in their ability to access and use needed health care as well as in their health status and outcomes. There remain large disparities by race and ethnicity.4 For example, compared to Whites, Hispanics fare worse across measures of health access and use (Figure 1) and Blacks fare worse across a range of health measures (Figure 2).5 Disparities also exist by income, with lower income people facing greater barriers to obtaining care and reporting worse health status than those with higher incomes.6 Although disparities are often viewed through the frames of race and income, they also occur across other dimensions. For example, research shows increased barriers for LGBT individuals, people with limited English proficiency, and individuals living in rural and inner city areas.7 Moreover, these groups are not mutually exclusive and there often are disparities among subgroups of populations.

Recent Advancements in Reducing Disparities

In recent years, there have been advancements in reducing disparities that reflect an increased federal focus on disparities and provisions to expand coverage and access under the ACA.

Health Coverage Expansions

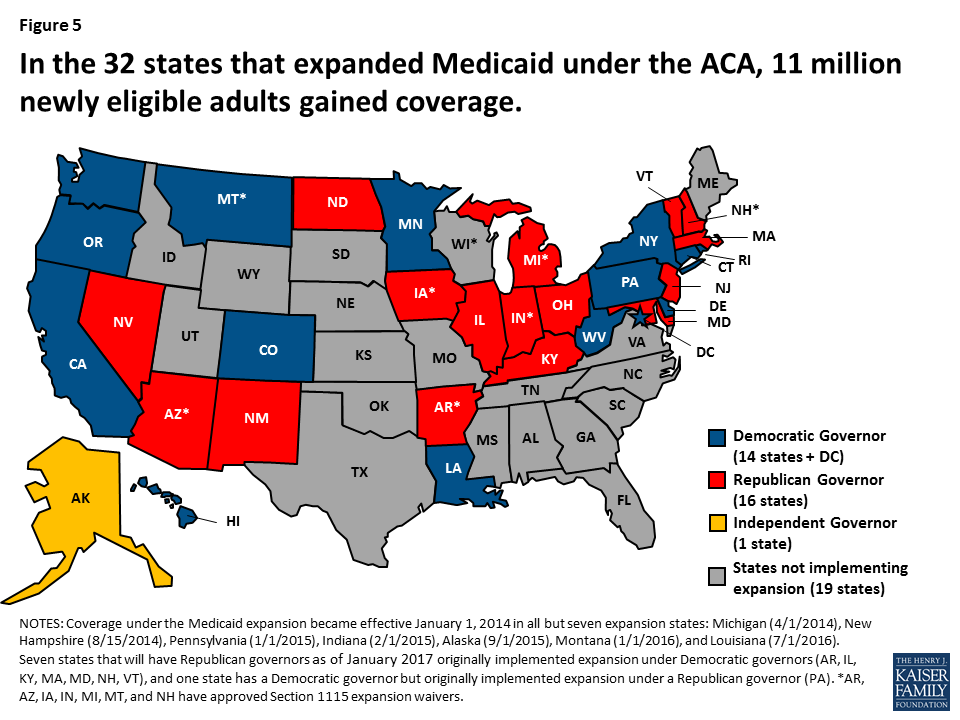

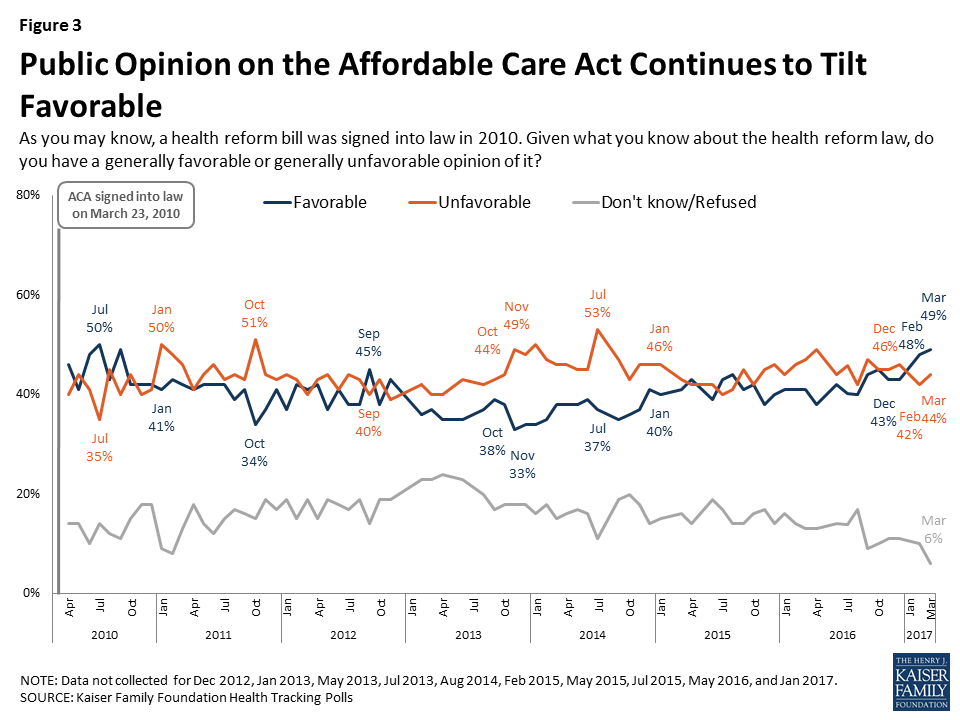

The ACA’s broad health insurance coverage expansions through Medicaid and the Marketplaces have played a central role in reducing health care disparities. Since implementation of these expansions in 2014, there have been large gains in coverage for low-income individuals and people of color, which helped narrow disparities in coverage (Figure 3).8 The Medicaid expansion played a particularly important role in these coverage gains.

Coverage gains among low-income individuals and by racial and ethnic group varied across states (Appendix Table 1). Figure 4 shows the states with the three largest percentage point reductions in their uninsured rate among the low-income population (below 200% of the federal poverty level, FPL) and among Hispanics, Blacks, and Whites. It shows that reductions in these states were often at least twice as large as the nationwide reduction for these groups. These states include a mix of those that have implemented the Medicaid expansion and those that have not as well as a mix of states led by both Republican and Democratic governors.

These coverage gains are expected to reduce disparities in access to and use of health care as well as health outcomes over the long-term. Research shows that health insurance makes a key difference in whether and when people get medical care, where they get their care, and ultimately how healthy they are.9 There also has been growing recognition that, although health insurance is key to health, social and environmental factors also influence health. An increasing number of initiatives within the health care system have emerged to address broader social determinants of health.10 Further, there has been increased recognition of the need to increase diversity within the health care workforce, enhance providers’ ability to deliver culturally and linguistically appropriate care, and increase provider access in rural and underserved areas.11

Enhanced Federal Focus and Investments in Public Health and Prevention

There has been an elevated focus on addressing health and health care disparities in recent years. In 2011, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) developed its first action plan to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities.12 The plan builds on organizational changes made within HHS under the ACA to prioritize and better coordinate efforts to reduce disparities. The ACA also strengthened data collection and research efforts to allow for improved measurement and monitoring of disparities and provided new protections from discrimination in health care.

The ACA included initiatives and investments through discretionary programs to strengthen public health and prevention, the health care workforce, and the delivery system that supported reduction of disparities. The ACA appropriated $11 billion over a five-year period (2011-2015) to support and enhance capacity of community health centers.13 Community health centers are a key source of care for low-income individuals and people of color.14 The ACA also contains provisions to increase the number of providers, particularly in underserved areas.15 Further, the ACA provided funding for and expanded initiatives to strengthen the public health workforce and infrastructure and prevention services, including the new Prevention and Public Health Fund.16

Remaining Challenges

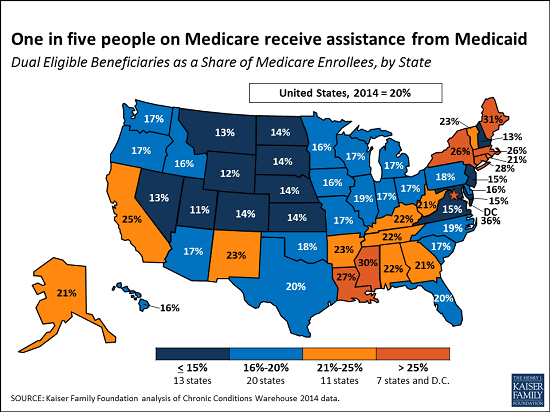

Despite nationwide gains in health insurance, differing state decisions to implement the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults have widened disparities in coverage. In states that expanded, parents and childless adults with incomes up to 138% FPL, which is about $28,200 for a family of three, are eligible for Medicaid. In contrast, among the 19 states that have not expanded, 10 of which are in the South, the median Medicaid eligibility limit for parents is 44% FPL, or less than $9,000 per year for a family of three, and other adults generally are not eligible. As a result of these differences, overall, Medicaid expansion states have realized larger gains in coverage and access to care than states that have not expanded.17 In particular, there are widening gaps between the South, which is home to many people of color and has high rates of chronic disease and poor health, and the rest of the nation.18

Further, although disparities in coverage have narrowed, low-income people and people of color still are more likely to be uninsured than those with higher incomes and Whites.19 Hispanics and American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) have the highest uninsured rates among racial and ethnic groups, and these disparities persist among children.20 In 2015, Hispanic children were nearly twice as likely as White children to be uninsured (7% vs. 4%), and AI/AN children were nearly five times as likely as White children to be uninsured (19% vs. 4%).21

Impact of ACA Repeal and Funding Reductions on Disparities

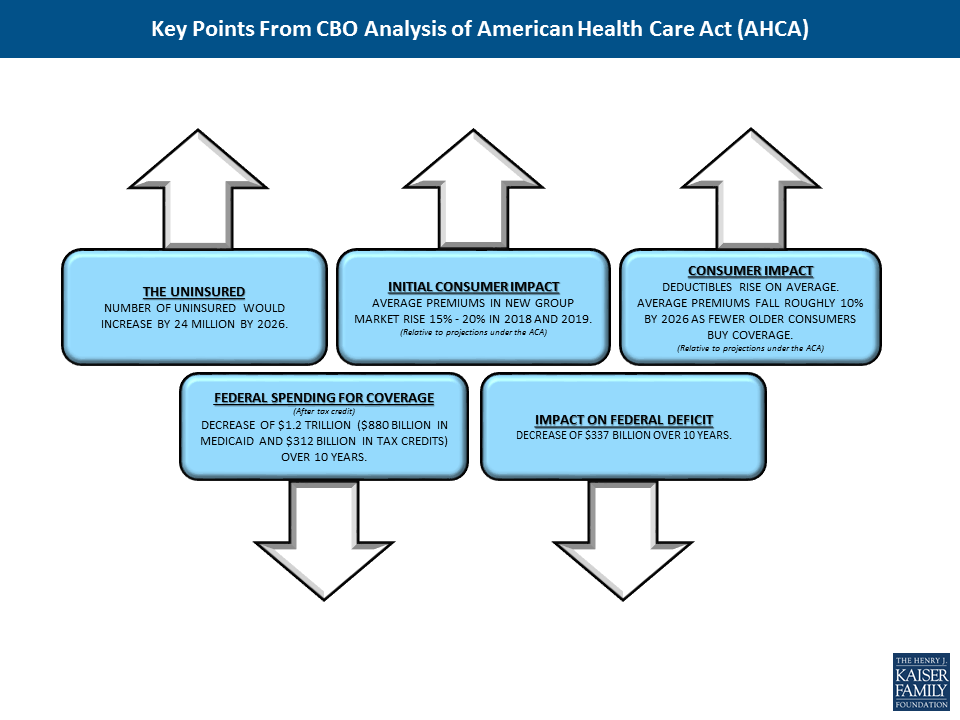

There is much at stake for health and health care disparities as Congress considers future funding decisions and broader health care reforms. The AHCA proposal to repeal and replace the ACA, as approved by the House Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce Committees and the House Budget Committee, would cap federal Medicaid financing, eliminate enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion, make changes to premium tax credits for private health insurance, and eliminate funding for the Prevention and Public Health Fund. In addition, the President’s 2018 budget proposes a 17.9% reduction in discretionary funding for HHS.

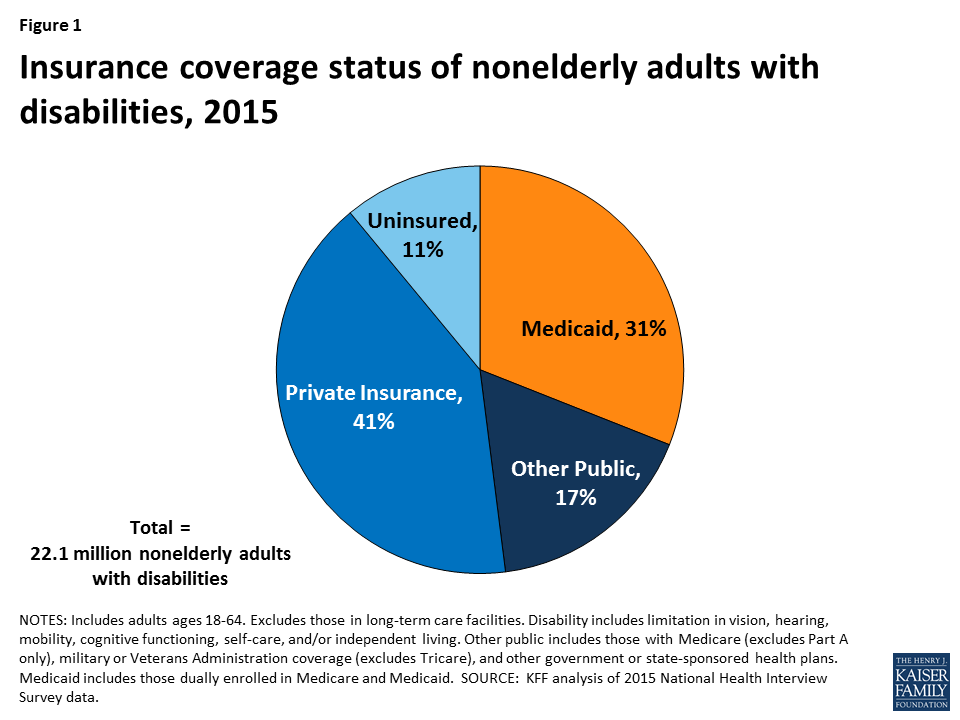

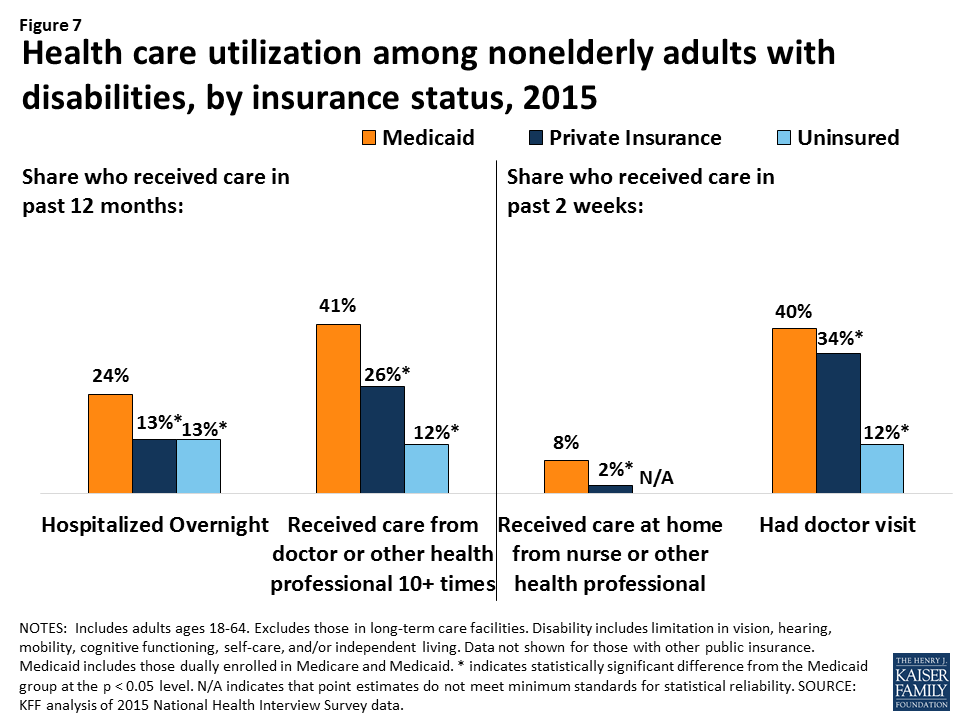

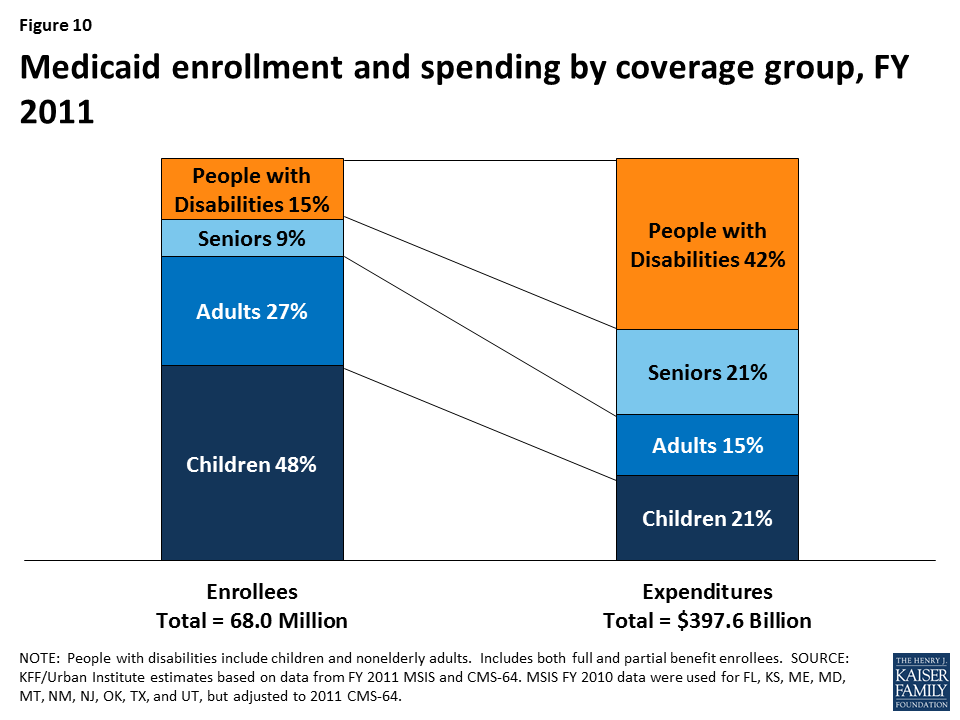

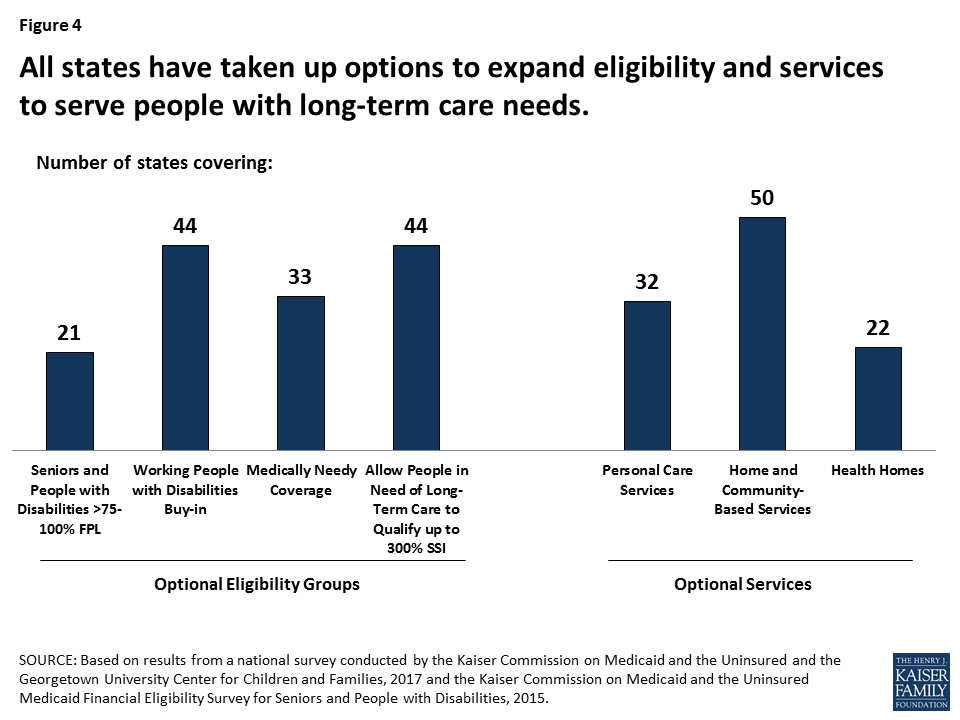

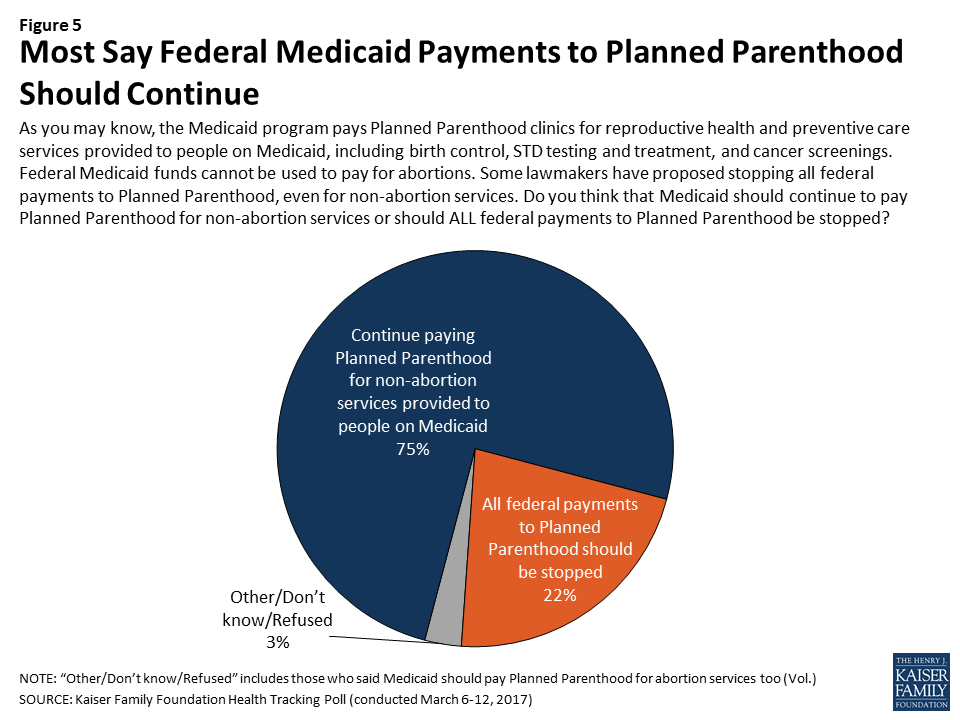

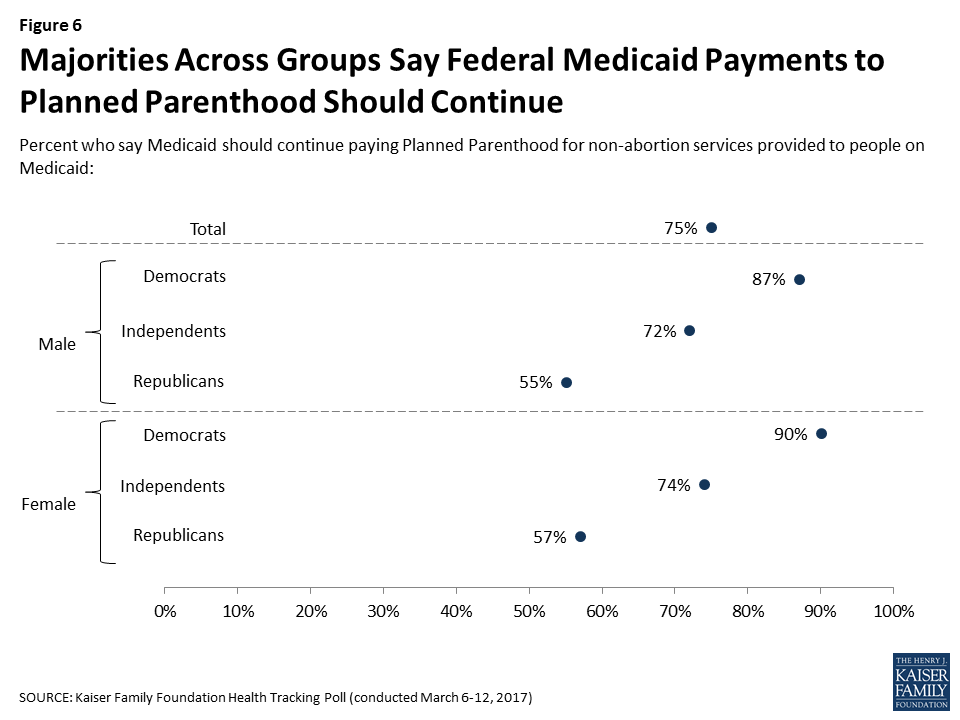

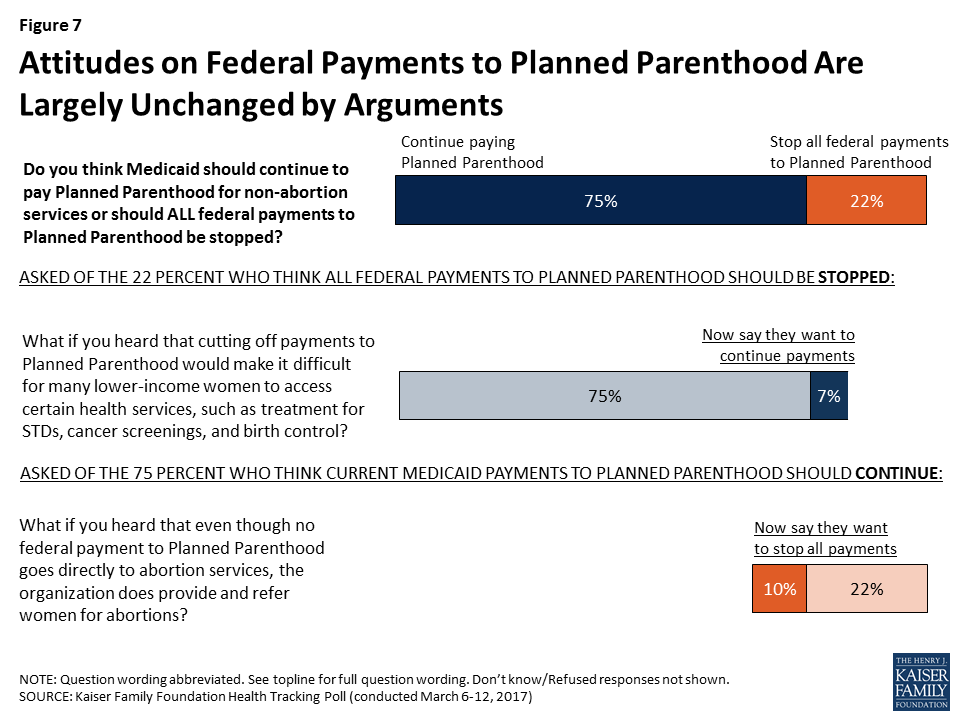

Changes to Medicaid under AHCA would disproportionately affect low-income individuals and people of color for whom the program is a central source of coverage. Medicaid provides coverage to over half (54%) of families with income below poverty and nearly four in ten (38%) of near-poor families, with incomes between 100% and 199% FPL (Figure 5). Moreover, it covers more than one in five nonelderly Hispanic, Black, and AI/AN adults. It plays an even larger role for children of color, covering nearly six in ten Hispanic (56%) and Black (54%) children and nearly half of AI/AN children (47%).

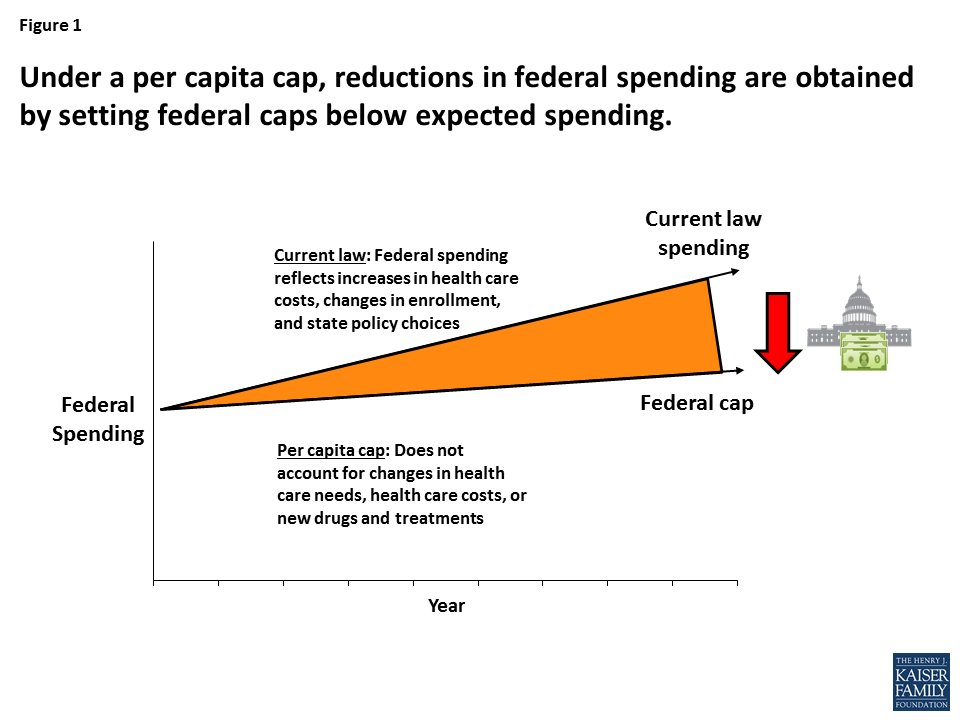

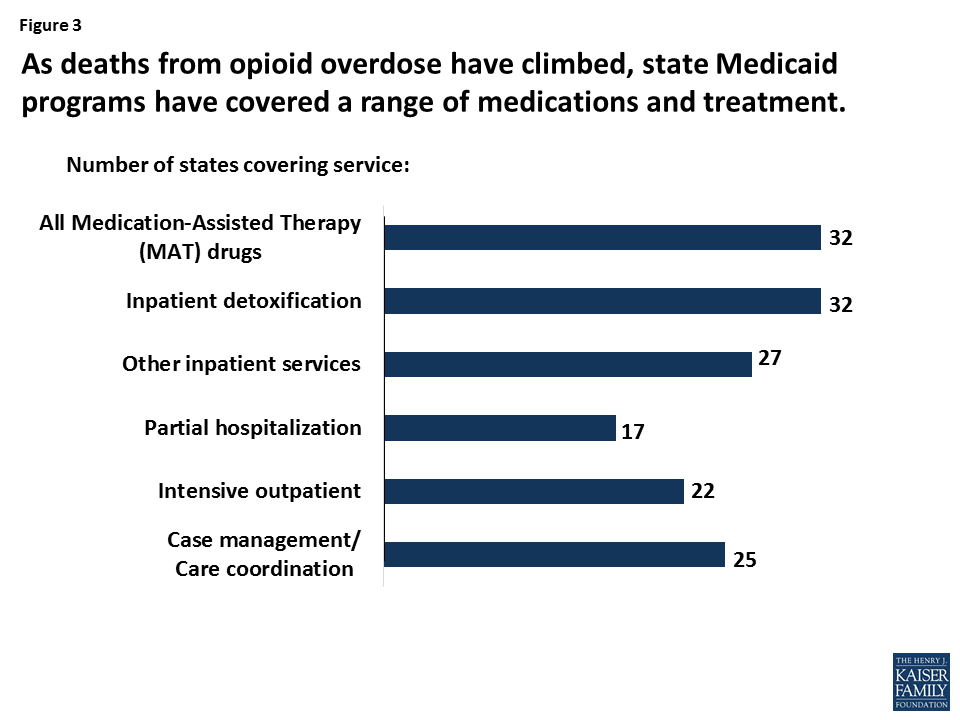

Capping federal Medicaid financing would fundamentally restructure the federal commitment to states to support care for individuals with the greatest health needs and lowest incomes. The cap would limit growth to a pre-set amount that is lower than projected growth in Medicaid spending.22 With more limited federal funds, states would need to increase spending or make program cutbacks such as reductions in eligibility, benefits, or provider payments that would lead to coverage losses and increased barriers to care for current enrollees. Capped financing also would lock in historic differences across states in benefits and spending and would not be responsive to changing health care costs, for example from new drug treatments or medical advancements, or new public health emergencies, such as the opioid epidemic.

Elimination of enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion would likely result in large coverage losses among low-income people and people of color. As noted, low-income individuals and people of color experienced large coverage gains under the ACA coverage expansions, and the Medicaid expansion played a particularly large role in these gains. If the enhanced federal match rate for the expansion is eliminated, as proposed by AHCA, states would face substantial increased costs to maintain this coverage. It is projected that some of the 32 states that have already expanded their programs would eliminate this coverage and that no additional states would expand in the future.23 Eight of the expansion states (AR, AZ, IL, IN, MI, NH, NM, and WA) have legislation requiring them to eliminate the expansion if the federal match rate is reduced. As a result of these changes, many adults currently enrolled in expansion coverage would likely become uninsured, leading to growing uninsured rates among low-income individuals and people of color that would reverse the recent narrowing of coverage disparities that occurred under the ACA.

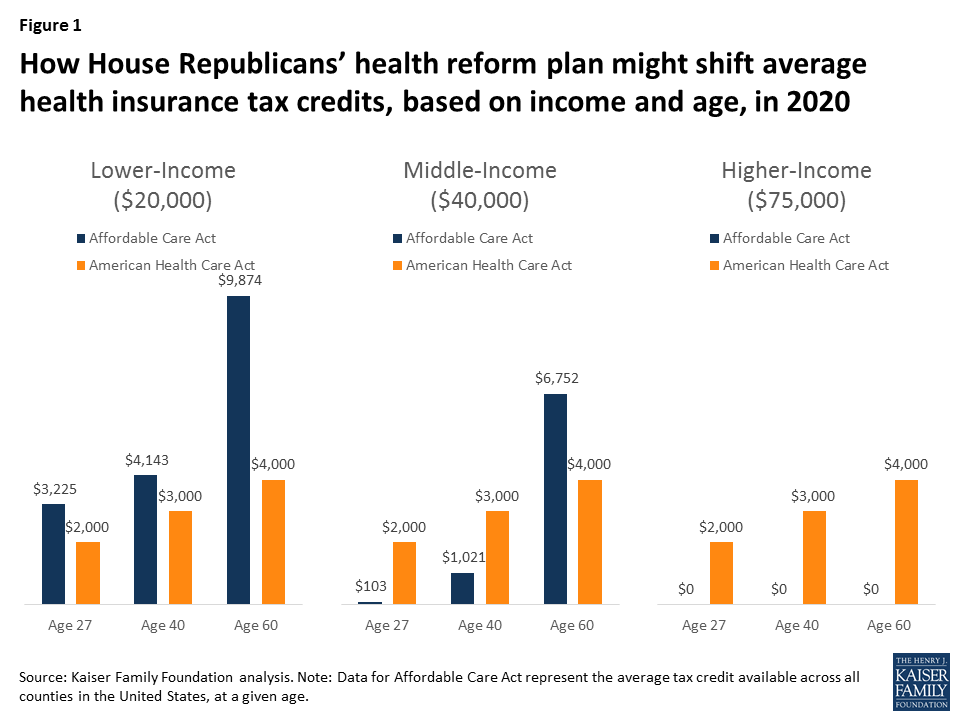

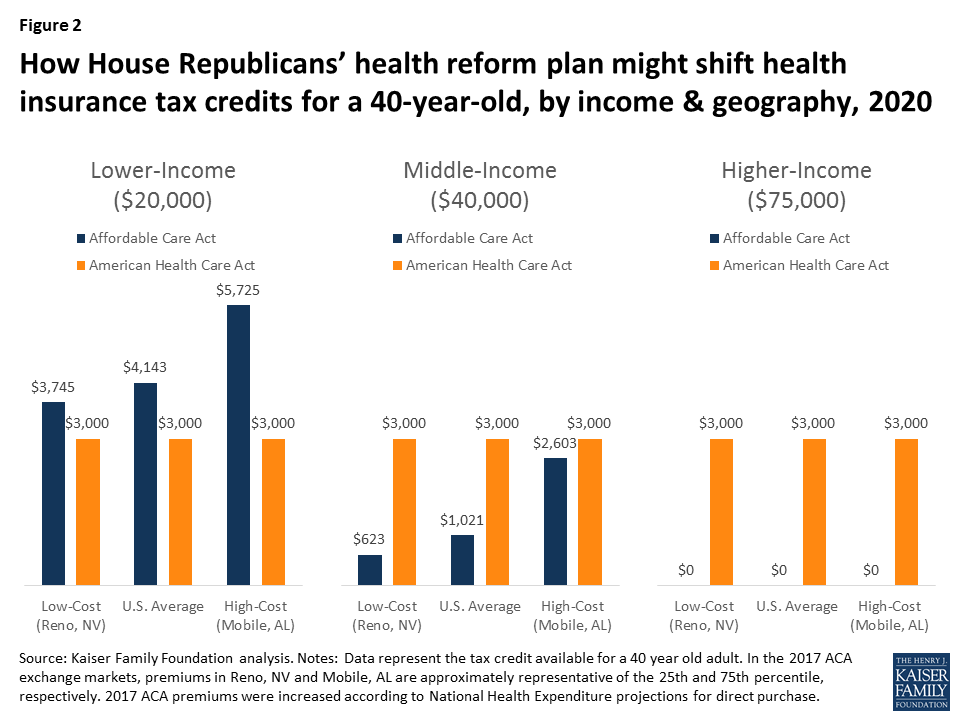

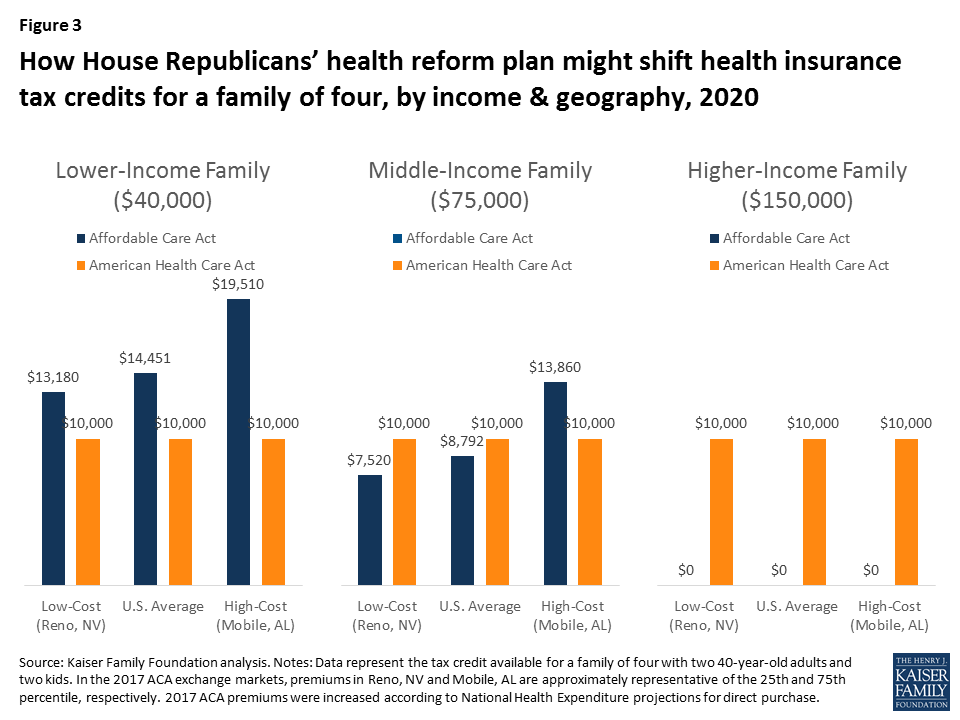

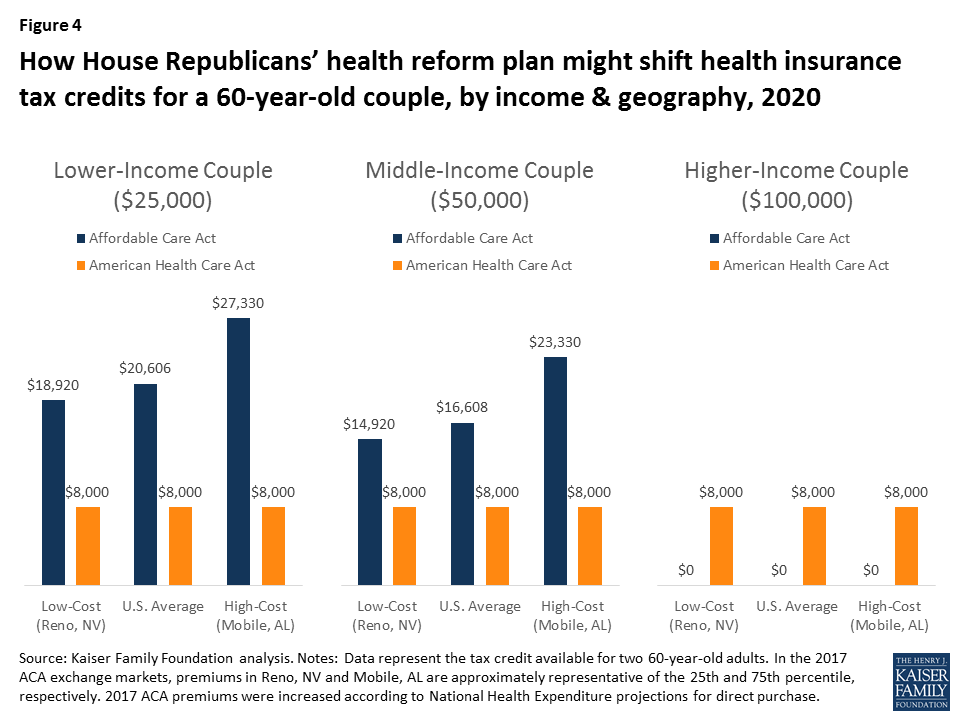

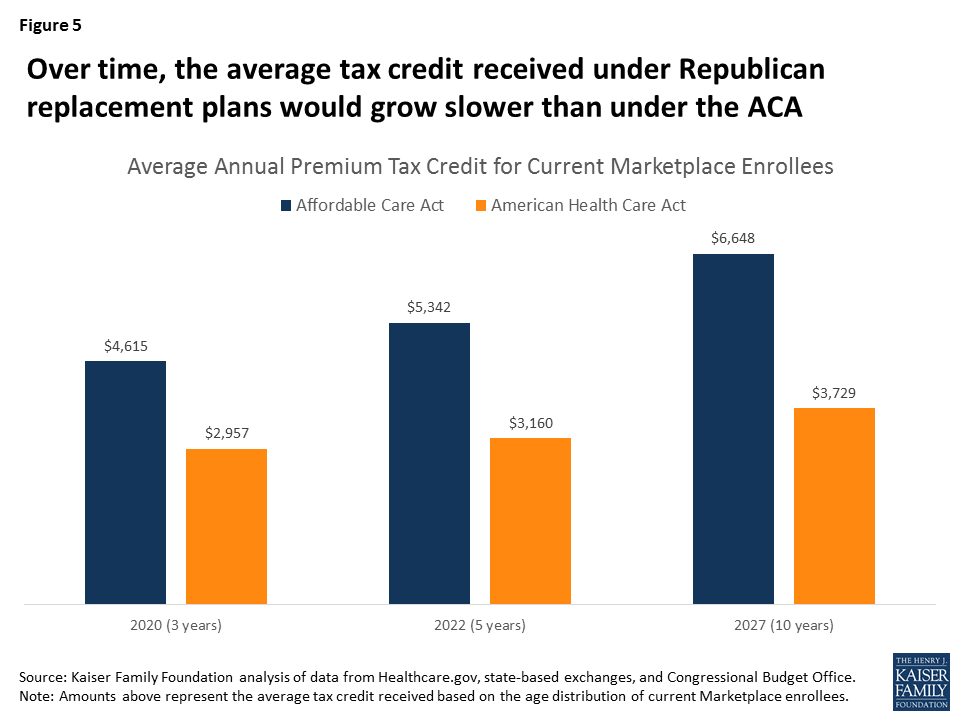

Changes in subsidies for private health coverage would also likely lead to coverage losses among low-income individuals and people of color. AHCA also would replace the ACA income-based premium tax credits for Marketplace coverage with flat premium tax credits based on age. Additionally, AHCA would eliminate the cost-sharing subsidies that lower deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs for lower-income individuals. These changes would reduce the levels of financial assistance to lower-income households, which would disproportionately affect people of color, since they are more likely to have lower family incomes compared to Whites. Without as much financial assistance, many low-income individuals and people of color will be unable to afford coverage and will become uninsured.

Elimination of funding for the Prevention and Public Health fund would reduce state capacity to provide these services at a time when there may be increased need due to coverage losses. Reductions in health insurance would increase strains on other parts of the health care system, including community health centers and public health programs. However, AHCA also would eliminate funding for the Prevention and Public Health Fund at the end of Fiscal Year 2018, and rescind any remaining unobligated funds.24 This fund supports public health and prevention services through immunization programs and grants to states to expand state and local capacity to provide prevention and public health services. It also provides targeted funding to states to strengthen their ability to respond to infectious disease and other public health threats, prevent childhood lead poisoning, and prevent healthcare-associated infections. In FY2016, over $625 million in grant funding was provided to states through the fund by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.25 A number of governors have pointed to the importance of this funding for supporting public health and prevention activities and cautioned against eliminating this funding under repeal.26

Other reductions in discretionary health spending may also reduce availability of services, limit progress expanding the health care workforce, and constrain continued research efforts to understand and address disparities. The President’s 2018 budget proposes a 17.9% reduction in funding for HHS. This reduction includes a 19% cut in the budget for the National Institutes of Health, which is central to research efforts to better understand disparities and develop effective interventions to eliminate them, as well as specified reductions in nurse training programs. The budget also proposes a new block grant program to states to address public health outbreaks, without a specified amount, and increased funding to address opioid misuse, but it is unclear to what extent these programs would offset decreases in services to meet the overall 17.9% funding reduction.

Looking Ahead

Maintaining gains in health insurance and support for public health and prevention, the health care workforce, and the delivery system are key for maintaining progress achieved to date and ongoing efforts to reduce disparities.Changes being considered to health insurance through repeal of the ACA and restructuring of Medicaid, including capping federal financing and eliminating enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion, could negatively affect disparities. People of color and low-income individuals would be disproportionately impacted by these changes since they had large coverage gains under the ACA and Medicaid is a central source of coverage for them. Reductions in health insurance and funding also would increase strains on other parts of the health care system, including community health centers and public health programs, which already face funding constraints and uncertainty regarding their future funding. Amid potential changes to health insurance, support for public health and prevention services and a health care workforce and delivery system that meets the needs of our increasingly diverse population is particularly important.

Appendix

| Appendix Table 1: Uninsured Rates among the Nonelderly, 2013 and 2015 | ||||||||||||

| Below 200% FPL | White | Black | Hispanic | |||||||||

| 2013 | 2015 | Percentage PointDifference | 2013 | 2015 | Percentage PointDifference | 2013 | 2015 | Percentage PointDifference | 2013 | 2015 | Percentage PointDifference | |

| United States | 25% | 17% | -8% | 12% | 8% | -4% | 17% | 12% | -5% | 26% | 17% | -9% |

| Implemented Medicaid Expansion-Democratic/Independent Governor | ||||||||||||

| California | 25% | 14% | -12% | 12% | 6% | -6% | 12% | 8% | -4% | 23% | 12% | -11% |

| Colorado | 25% | 17% | -7% | 11% | 8% | -3% | 22% | 13% | -9% | 21% | 14% | -8% |

| Connecticut | 22% | 13% | -10% | 9% | 5% | -3% | 13% | N/A | N/A | 26% | 11% | -15% |

| Delaware | 14% | 11% | -3% | 7% | 6% | -1% | 8% | 8% | 1% | 20% | 15% | -5% |

| District of Columbia | 12% | 7% | -4% | 6% | 3% | -3% | 10% | 6% | -5% | 15% | 8% | -6% |

| Hawaii | 9% | 10% | 0% | 11% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Louisiana | 25% | 18% | -6% | 13% | 11% | -2% | 20% | 14% | -7% | 29% | 18% | -12% |

| Minnesota | 15% | 17% | 2% | 6% | 4% | -2% | 15% | N/A | N/A | 19% | 20% | 1% |

| Montana | 28% | 18% | -10% | 18% | 11% | -7% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 19% | N/A |

| New York | 16% | 12% | -5% | 8% | 6% | -2% | 14% | 9% | -6% | 15% | 10% | -4% |

| Oregon | 21% | 11% | -10% | 13% | 7% | -6% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 27% | 14% | -13% |

| Pennsylvania | 23% | 13% | -9% | 10% | 6% | -4% | 17% | 13% | -4% | 17% | 9% | -9% |

| Rhode Island | 19% | 8% | -11% | 9% | 4% | -5% | 19% | N/A | N/A | 17% | 12% | -5% |

| Washington | 26% | 12% | -15% | 10% | 7% | -3% | 19% | N/A | N/A | 27% | 16% | -11% |

| West Virginia | 23% | 11% | -13% | 14% | 8% | -6% | 16% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Alaska | 25% | 27% | 2% | 13% | 10% | -3% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 15% | N/A | N/A |

| Implemented Medicaid Expansion-Republican Governor | ||||||||||||

| Arizona | 29% | 22% | -6% | 15% | 10% | -5% | 16% | N/A | N/A | 30% | 17% | -13% |

| Arkansas | 24% | 16% | -8% | 16% | 8% | -8% | 20% | 9% | -11% | 27% | 31% | 4% |

| Illinois | 20% | 11% | -9% | 9% | 6% | -3% | 17% | 9% | -8% | 20% | 11% | -9% |

| Indiana | 24% | 19% | -5% | 12% | 9% | -3% | 20% | 15% | -5% | 34% | 22% | -13% |

| Iowa | 18% | 13% | -5% | 8% | 6% | -3% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 18% | 13% | -5% |

| Kentucky | 26% | 10% | -17% | 15% | 7% | -8% | 11% | N/A | N/A | 47% | N/A | N/A |

| Maryland | 22% | 13% | -9% | 10% | 5% | -5% | 12% | 8% | -4% | 32% | 15% | -17% |

| Massachusetts | 5% | 6% | 1% | 3% | 5% | 2% | N/A | 6% | N/A | 5% | 4% | -2% |

| Michigan | 21% | 10% | -11% | 11% | 6% | -5% | 19% | 7% | -12% | 15% | 16% | 1% |

| Nevada | 35% | 18% | -17% | 16% | 9% | -7% | 24% | N/A | N/A | 34% | 19% | -15% |

| New Hampshire | 27% | 10% | -18% | 13% | 6% | -7% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 28% | N/A | N/A |

| New Jersey | 26% | 17% | -10% | 9% | 7% | -3% | 16% | 8% | -8% | 22% | 18% | -3% |

| New Mexico | 29% | 19% | -10% | 14% | 8% | -5% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 22% | 15% | -7% |

| North Dakota | 25% | 16% | -9% | 10% | 7% | -3% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 17% | N/A | N/A |

| Ohio | 24% | 13% | -10% | 13% | 6% | -6% | 17% | 8% | -9% | 21% | 18% | -4% |

| Vermont | 15% | 10% | -5% | 9% | 6% | -3% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Has Not Implemented Medicaid Expansion-Democratic Governor | ||||||||||||

| North Carolina | 29% | 21% | -7% | 14% | 10% | -4% | 16% | 14% | -2% | 38% | 30% | -8% |

| Virginia | 27% | 22% | -4% | 11% | 8% | -3% | 14% | 14% | 1% | 25% | 21% | -4% |

| Has Not Implemented Medicaid Expansion-Republican Governor | ||||||||||||

| Alabama | 27% | 18% | -9% | 17% | 11% | -6% | 17% | 14% | -3% | 29% | 28% | -1% |

| Florida | 33% | 23% | -10% | 18% | 13% | -5% | 24% | 16% | -8% | 29% | 19% | -9% |

| Georgia | 31% | 25% | -6% | 14% | 12% | -2% | 19% | 16% | -2% | 44% | 30% | -14% |

| Idaho | 28% | 21% | -7% | 15% | 11% | -4% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 23% | 23% | 0% |

| Kansas | 23% | 19% | -4% | 9% | 9% | 0% | 11% | 20% | 10% | 29% | 21% | -8% |

| Maine | 16% | 8% | -8% | 11% | 6% | -5% | N/A | 0% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mississippi | 24% | 21% | -2% | 12% | 14% | 2% | 19% | 13% | -6% | 58% | 30% | -28% |

| Missouri | 24% | 21% | -3% | 12% | 8% | -4% | 14% | 16% | 2% | 20% | 28% | 7% |

| Nebraska | 19% | 19% | 1% | 8% | 8% | -1% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 18% | 18% | 0% |

| Oklahoma | 26% | 21% | -4% | 15% | 10% | -5% | 14% | 23% | 9% | 24% | 27% | 3% |

| South Carolina | 32% | 19% | -13% | 15% | 13% | -2% | 22% | 11% | -12% | 43% | 24% | -19% |

| South Dakota | 20% | 19% | -1% | 9% | 8% | -2% | 14% | N/A | N/A | 22% | N/A | N/A |

| Tennessee | 24% | 19% | -5% | 12% | 11% | -1% | 18% | 12% | -6% | 41% | 30% | -11% |

| Texas | 35% | 29% | -6% | 14% | 12% | -2% | 20% | 17% | -3% | 32% | 25% | -7% |

| Utah | 24% | 20% | -4% | 11% | 9% | -2% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 25% | 21% | -4% |

| Wisconsin | 17% | 15% | -1% | 9% | 7% | -2% | 17% | N/A | N/A | 19% | 16% | -2% |

| Wyoming | 29% | 18% | -11% | 16% | 10% | -6% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 34% | 13% | -21% |

| SOURCES: Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on the Census Bureau’s March 2014 and March 2016 Current Population Surveys (CPS: Annual Social and Economic Supplements).NOTES: Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race; all other racial/ethnic groups are non-Hispanic. N/A: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% are not provided. | ||||||||||||

Endnotes

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report and 5th Anniversary Update on the National Quality Strategy, (Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, May 2015), https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr15/2015nhqdr.pdf. ↩︎

- Thomas LaVeist, Darrell Gaskin, and Patrick Richard, The Economic Burden of Health Inequalities in the United States, (Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, September 2009), http://www.hhnmag.com/ext/resources/inc-hhn/pdfs/resources/Burden_Of_Health_FINAL_0.pdf. ↩︎

- Sandra L. Colby and Jennifer M. Ortman, Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060, (Washington, D.C., U.S. Census Bureau, March 2015), https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. ↩︎

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report and 5th Anniversary Update on the National Quality Strategy, op cit. and Samantha Artiga et. al., Key Facts on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2016), http://files.kff.org/attachment/Chartpack-Key-Facts-on-Health-and-Health-Care-by-Race-and-Ethnicity. ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga et. al., Key Facts on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity, op cit. ↩︎

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report and 5th Anniversary Update on the National Quality Strategy, op cit. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Health and Access to Care and Coverage for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Individuals in the U.S., (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2016), https://modern.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/health-and-access-to-care-and-coverage-for-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-individuals-in-the-u-s/; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Overview of Health Coverage for Individuals with Limited English Proficiency, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, August 2012), http://modern.kff.org/uninsured/8343.cfm; and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013 National Healthcare Disparities Report, (Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, May 2014), https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/2013nhdr.pdf. ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga, et. al., Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity: Examining Changes Under the ACA and the Remaining Uninsured, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2016), https://modern.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-examining-changes-under-the-aca-and-the-remaining-uninsured/ and Rachel Garfield, et. al., The Uninsured: A Primer – Key Facts about Health Insurance and the Uninsured in the Wake of National Health Reform, (Washington, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November 2016), https://modern.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-in-the-wake-of-national-health-reform/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Key Facts About the Uninsured Population, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2016), https://modern.kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/. ↩︎

- Harry J Heiman and Samantha Artiga, Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity, op cit. ↩︎

- Office of Minority Health, National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care: A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 2013), https://www.thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/pdfs/EnhancedCLASStandardsBlueprint.pdf and The Commonwealth Fund, State and Federal Efforts to Enhance Access to Basic Health Care, (New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund, March 2010), http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletters/states-in-action/2010/mar/march-april-2010/feature/feature. ↩︎

- Department of Health and Human Services, HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, op cit. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Summary of the Affordable Care Act, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2013), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/summary-of-the-affordable-care-act/. ↩︎

- Julia Paradise, et. al., Community Health Centers: Recent Growth and the Role of the ACA, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2017), https://modern.kff.org/report-section/community-health-centers-recent-growth-and-the-role-of-the-aca-issue-brief/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Summary of the Affordable Care Act, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2013), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/summary-of-the-affordable-care-act/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Larisa Antonisse, et. al., The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review/. ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga and Anthony Damico, Health and Health Coverage in the South: A Data Update, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, February 2016), https://modern.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/health-and-health-coverage-in-the-south-a-data-update/. ↩︎

- Michael E Martinez, Emily P Zammitti, and Roben A Cohen, Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-September 2016, (Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, February 2017), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201702.pdf. ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga, et. al., Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity: Examining Changes Under the ACA and the Remaining Uninsured, op cit. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Congressional Budget Office (CBO), American Health Care Act: Budget Reconciliation Recommendations of the house Committees on Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce, March 9, 2017, (Washington, DC: CBO, March 2017), https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/americanhealthcareact.pdf. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Summary of the American Health Care Act, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2017), http://files.kff.org/attachment/Proposals-to-Replace-the-Affordable-Care-Act-Summary-of-the-American-Health-Care-Act. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Accomplishing CDC’s Mission with Investments from the Prevention & Public Health Fund, FY 2010- FY 2016, (Atlanta, GA: CDC, n.d.), https://www.cdc.gov/funding/documents/cdc-pphf-funding-impact.pdf. ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga, et. al., Views of Governors and Insurance Commissioners on ACA Repeal and Changes to Medicaid: Responses to a Congressional Request for State Input on Health Reform, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/views-of-governors-and-insurance-commissioners-on-aca-repeal-and-changes-to-medicaid-responses-to-a-congressional-request-for-state-input-on-health-reform/. ↩︎