Hispanics Saw Greatest Improvement in Health Coverage, Access, and Use Since ACA

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Summary

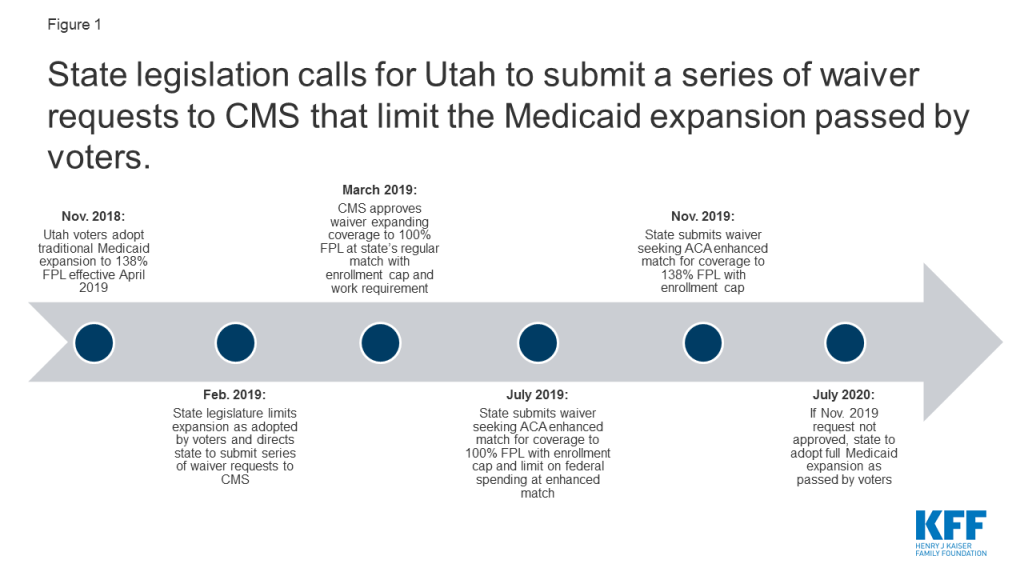

Since Utah voters approved a November 2018 ballot measure to adopt the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), the state legislature has taken steps to roll back the full expansion. The state enacted a law in February 2019 that amended the voter-approved ballot measure, requiring the state to submit a series of Section 1115 waiver requests. This brief provides additional detail about the ballot measure, the state legislation, the status of the required waiver submissions, and the broader implications of Utah’s waivers for other states.

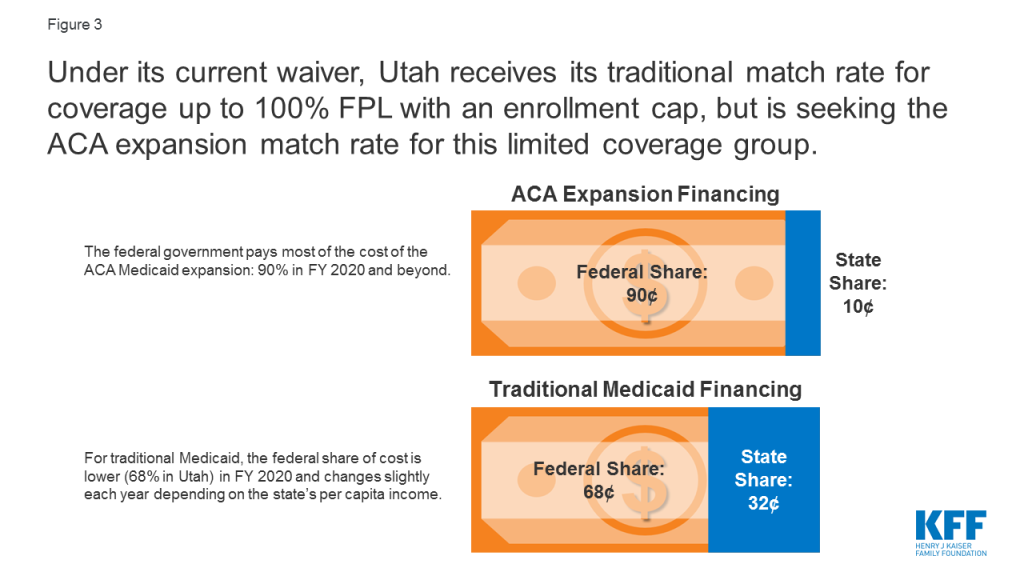

As in Idaho and Nebraska, Utah voters supported a November 2018 ballot measure to adopt the full Medicaid expansion as set out in the ACA. Utah voters approved a full ACA expansion to cover nearly all adults with income up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $17,236/year for an individual in 2019), an April 1, 2019, implementation date, and a state sales tax increase as the funding mechanism for the state’s share of expansion costs. By implementing a full ACA expansion, Utah would qualify for the substantially enhanced (93% in 2019 and 90% in 2020 and thereafter) federal matching funds. The expansion population in Utah includes childless adults ages 19-64 with income from 0% to 138% FPL and parent/caretakers ages 19-64 with income from 60% to 138% FPL.2 The fiscal note from the ballot initiative estimated that approximately 150,000 newly eligible individuals would enroll in Medicaid in fiscal year 2020.

However, the Utah legislature significantly changed and limited the coverage expansion that the voters adopted. Utah is one of 11 states (out of the 21 states that allow state laws to be adopted via a ballot initiative) that have no restrictions on how soon or with what majority state legislators can repeal or amend voter-initiated statutes. Utah Governor Gary Herbert signed Senate Bill 96 into law on February 11, 2019. The state released an implementation toolkit that follows the legislation in calling for multiple steps to implement an expansion of Medicaid coverage to adults in ways that differ from a full ACA expansion (Figure 1).

On March 29, 2019, CMS approved an amendment to Utah’s existing Section 1115 demonstration waiver to expand Medicaid to a capped number of adults with income up to 100% FPL beginning on April 1, 2019, at the state’s regular Medicaid matching rate, not the enhanced ACA matching rate.3 The authority to cover this “Adult Expansion Population” expires on January 1, 2021. The Adult Expansion Population under the waiver includes childless adults ages 19-64 with income from 0 to 100% FPL4 and parent/caretakers ages 19-64 with income from 60% FPL to 100% FPL,5 a more limited coverage expansion than the 138% FPL approved by the voters (Figure 2). The state estimates that approximately 70,000 to 90,000 people will be covered under the waiver with financial eligibility limited to 100% FPL, about 40,000 fewer compared to a full ACA expansion to 138% FPL.6

Instead of the 90% enhanced federal matching rate tied to newly eligible adults under a full ACA expansion, Utah is receiving its current, traditional federal matching rate of 68%. This lower matching rate will result in higher state costs for expanding coverage to 100% FPL than for a full expansion to 138% FPL (Figure 3).7 Utah refers to the March 2019 waiver amendment as the “Bridge Plan” because the state is seeking further waiver amendments as required by Senate Bill 96 and described in the text below. Utah’s pre-ACA coverage expansion, authorized by its waiver prior to the Bridge Plan amendment, provided limited benefits and preventive care (see Box 1 below).

Utah’s amended waiver includes an enrollment cap to be imposed at state option on the Adult Expansion Population, meaning that not all eligible people may be able to enroll in coverage. The waiver allows the state to close enrollment for the Adult Expansion Population, which could limit enrollment further than the coverage estimates noted above. The waiver does not specify a pre-determined maximum number of people to be covered but instead allows the state to stop enrolling eligible people “if projected costs exceed state appropriations.” If the enrollment cap is reached, the state will not maintain a waiting list; instead, eligible individuals will have their applications denied and will have to reapply for coverage when enrollment re-opens. Consequently, individuals who apply at the beginning of a state fiscal year could be more likely to gain coverage than those who apply later in the fiscal year, even though they are otherwise eligible, if the state imposes the enrollment cap. It is possible that individuals with lower incomes or higher needs, compared to those already enrolled, might be barred from enrolling in coverage as a result of the timing of their application due to the enrollment cap.

Utah’s amended waiver also includes a work requirement as a condition of eligibility for the Adult Expansion Population, beginning no sooner than January 1, 2020.8 In Utah, individuals subject to the work requirement must complete certain activities within the first three months of each 12-month eligibility period or qualify for an exemption. Possible exemptions include age of 60 or older, pregnancy, responsibility to care for a dependent under age six in the same household or a disabled person, and physical or mental inability to meet the work requirement as determined by a medical professional, among others. Those who fail to do so will lose coverage for the rest of the year or until they fulfill the requirement. Qualifying activities include registering for work through the state’s online system, completing an online employment training needs assessment, completing online job training modules identified through the assessment, and applying for work with at least 48 potential employers.

In accordance with SB 96, Utah submitted its “Per Capita Cap” (PCC) waiver application to CMS on July 31, 2019, which includes a request to receive the 90/10 ACA enhanced matching rate for expansion adult coverage up to 100% FPL; however, CMS guidance states that such a policy would not be approved.9 The waiver would move all expansion adults (parents 60-100% and childless 0-100%, including the Targeted Adult group) and the waiver services provided to these populations from the existing waiver to the new waiver. The Targeted Adult population includes adults ages 19-64 without dependent children with income up to 5% FPL who are chronically homeless or involved in the criminal justice system and in need of substance use or mental health treatment.

Days before Utah’s submission, a CMS statement indicated that it would not approve the 90/10 ACA enhanced matching rate for an expansion population smaller than the full group up to 138% FPL, arguing that such policies would “invite continued reliance on a broken and unsustainable Obamacare system.”10 Therefore, the result of no partial expansion is similar to the prior administration, but for different publicly-stated reasons.11 In its submission letter, the state provided several reasons for submitting the waiver as envisioned in SB 96, including the unknown outcome of the Texas vs U.S. litigation challenging the ACA, value in getting a formal response from CMS, and the state’s hopes for approval of other waiver provisions. CMS also indicated in an August 16, 2019 letter12 to Utah that it would not authorize an enrollment cap with enhanced ACA matching funds for the expansion group as Utah requested; see more on this guidance in the Fallback Plan section below.

The waiver also requests a limit on enhanced federal funding through what the state describes as a “per capita cap” funding mechanism. Under the waiver request, an aggregate annual per capita cap would be calculated based on the weighted total of separate per capita caps for three enrollment groups: targeted adults and enrollees receiving IMD services for substance use disorder (SUD), expansion parents, and expansion adults without children.13 Expenditures in excess of the total per capita cap but within budget neutrality would receive the State’s traditional FMAP rather than the enhanced matching rate.14 The state would establish per enrollee amounts for each group for a base year and apply a trend rate for future demonstration years.

Unlike federal legislative per capita cap proposals, the PCC waiver request would not impose a cap on all federal Medicaid dollars. The state request would apply only to the enhanced matching dollars and not all federal matching dollars, include a mechanism for automatic rebasing, and allow for adjustments for unforeseen events like a public health emergency, natural disaster, major economic event, new federal mandate, or any subsequent waivers approved by CMS that affect the populations under this waiver. The state assumes a “with waiver” per capita cap growth rate of 4.2%, lower than the anticipated “without waiver” per member per month cost growth rate of 5.3%.

Among other provisions, the PCC waiver proposal also includes a lockout period for “Intentional Program Violations” (IPV) committed when documenting Medicaid eligibility. The state seeks waiver authority to impose a six-month coverage lockout period if an individual commits an IPV. Utah defines an IPV as occurring when there is “clear and convincing evidence that the individual knowingly, willingly, or recklessly provided false or misleading information with an intent to receive benefits to which he or she was not eligible to receive” and may find the individual responsible to repay any medical assistance received for which he or she was not eligible. An IPV would include not reporting a change in eligibility within ten days with the intent to obtain benefits to which the enrollee is not entitled. Under Utah’s existing Medicaid policy, the state is currently determining IPVs using this definition and assessing overpayments using an administrative hearing process. The new authority that the PCC waiver seeks is to impose coverage lockouts when an IPV determination is made. Utah also has a separate process where certain cases are referred for potential criminal fraud prosecution in court.

The waiver request includes other eligibility, benefit, and process changes. The PCC waiver’s other new provisions include expenditure authority for housing-related services and supports and authority to provide up to 12-month continuous Medicaid eligibility. The state asks for waiver authority to limit these provisions to certain geographic areas or populations that are not specified in the waiver. The waiver also seeks authority to not allow hospitals to make presumptive eligibility determinations and to allow the state to continue a limited benefit package for expansion parents. Finally, the waiver seeks to waive some managed care rules, including advance CMS approval of actuarially sound rates, managed care contracts, and directed payments.

In addition to the new provisions, the PCC waiver seeks to maintain authority to implement provisions approved in March 2019, including the enrollment cap (currently approved at the regular federal matching rate) and the work requirement for the expansion population. As noted above, CMS has indicated that it would not approve the enhanced federal matching rate for the ACA expansion in the context of enrollment caps. Based on its experience with SNAP work requirements, the state estimates that approximately 70 percent of expansion adults (49,000-63,000 individuals) will meet an exemption to the work requirements. The state further projects that, among individuals who do not meet an exemption or good cause reason, approximately 75-80 percent will comply with the work requirements. Other provisions that were approved in March 2019 include dental benefits for Targeted Adults receiving SUD treatment, SUD treatment in institutions for mental disease (IMD), a targeted SUD residential withdrawal pilot in Salt Lake County, and a waiver of EPSDT for 19- and 20-year-olds.

As directed by SB 96, Utah submitted its Fallback Plan waiver request on November 4, 2019, seeking authority for a coverage expansion up to 138% FPL with the 90/10 ACA enhanced matching funds and an enrollment cap.15 In its submission letter, Utah says that CMS rejected its PCC waiver request, although the waiver is still listed as pending on CMS’ website as of November 14, 2019. Like the PCC waiver, the Fallback Plan includes coverage lockouts for intentional program violations, elimination of hospital presumptive eligibility, expenditure authority for housing-related services and supports, and modifications for managed care rules; unlike the PCC waiver, it does not request the authority to provide 12-month continuous Medicaid eligibility for the expansion population. The Fallback Plan seeks to continue the work requirement and enrollment cap approved in March 2019 but does not seek a per capita cap on federal funds at the enhanced matching rate.

As noted above, CMS has indicated that it would not authorize an enrollment cap with enhanced ACA matching funds for the expansion group, as Utah requested in both the PCC and Fallback waivers. In addition to expanding coverage to 138% FPL and receiving the 90/10 ACA enhanced match rate, the Fallback Plan requests to continue the enrollment cap approved by CMS in March 2019. In an August 16, 2019, letter16 to Utah following the state’s PCC waiver submission, CMS noted that, if implemented, an enrollment cap would “have the effect of limiting enrollment to less than the full group otherwise eligible for Medicaid, which would be tantamount to ‘partial expansion.’” CMS noted that it would therefore not authorize the enhanced matching rate if the enrollment caps were implemented. In its submission letter, Utah provided two reasons for submitting the Fallback Plan waiver as envisioned in SB 96 despite this CMS guidance: the unknown outcome of the Texas vs U.S. litigation challenging the ACA and the state’s hopes for approval of other waiver provisions. As explained in Box 1, enrollment caps are no longer necessary to ensure federal budget neutrality because the ACA now allows states to access federal Medicaid funds for this coverage directly through the creation of the new adult eligibility pathway and the availability of federal matching funds.

Box 1: Coverage Expansion under Utah’s Waiver Prior to the ACA

In 2014, the ACA for the first time authorized federal Medicaid matching funds for coverage for nearly all nonelderly adults. Prior to 2014, federal Medicaid funds could only be used to cover pregnant women, parent/caretakers, children, seniors, and people with disabilities. Adults without dependent children were ineligible for Medicaid, no matter how poor they were. Before the ACA, some states used Section 1115 waivers to establish coverage expansions beyond the limits of federal law. Because federal Medicaid funds could not be accessed directly to cover these adults, these waivers included provisions to generate savings to fund coverage expansions, such as limited benefit packages, premiums, and/or mandatory managed care enrollment, and sometimes enrollment caps as a way to limit federal spending and ensure federal budget neutrality.17 However, budget neutrality is no longer a consideration for such coverage expansions under waivers now that federal Medicaid law, as amended by the ACA, includes an eligibility pathway and allows states to receive federal Medicaid matching funds to cover nearly all nonelderly adults, including those without dependent children, up to 138% FPL without the need for a waiver.

Utah’s existing Section 1115 waiver was first approved in 2002 and included a pre-ACA coverage expansion (called the Primary Care Network, PCN) to parents with income above the state plan limit (60% FPL) and childless adults (for whom no state plan coverage was available). As of March 2019, the PCN income limit was 100% FPL. The PCN coverage expansion provided a limited benefit package of primary and preventive services18 to a capped number of these adults and was funded by reduced benefits for traditional low-income (categorically and medically needy) parents. The March 2019 waiver amendment suspends authority for Utah’s pre-ACA PCN coverage expansion and moves the 17,500 parents and childless adults in the PCN group as of March 2019 to the new “Adult Expansion Population” (described in the section above on Utah’s Amended Waiver Approved Mach 2019) effective April 1, 2019.19

The Fallback Plan waiver requests to expand the eligibility criteria for the Targeted Adult group and seeks authority to suspend enrollment for sub-populations of Targeted Adult populations. The Targeted Adult group is comprised of three populations and Utah currently has authority to suspend enrollment for the entire Targeted Adult group or separately for any of the three populations. In the Fallback Waiver, Utah seeks to expand the Targeted Adult Medicaid criteria to include three new sub-populations: homeless victims of domestic violence, individuals who are court ordered to receive substance abuse or mental health treatment, and individuals on probation or parole with serious mental illness and/or serious substance use disorder. Utah estimates that an additional 7000 individuals will be eligible for the Targeted Adult group due to the expanded criteria. Any suspension of enrollment of Targeted Adult populations or sub-populations would occur through the state’s administrative rule-making process. If enrollment is suspended for Targeted Adults, individuals could be eligible in the Expansion Adult group (provided that enrollment has not been suspended there); however, unlike the Expansion Adult group, Targeted Adults receive 12-month continuous eligibility and dental benefits (if receiving substance use disorder treatment services).

Under the Fallback Plan waiver, adults with incomes between 100% and 138% of the FPL would pay monthly premiums in order to maintain coverage under Medicaid expansion. Monthly premiums would be $20 for a single individual or $30 for a married couple. Utah requests the authority to raise these premiums to reflect annual increases in the FPL through the state administrative rulemaking process. Beneficiaries who fail to pay their premium in the month prior to the month of eligibility would be dis-enrolled from Medicaid and required to pay all past-due premiums to re-enroll, unless it had been more than six months from when coverage ended. Members of federally recognized tribes and those identified as medically frail would be exempt from paying premiums. The state estimates that 40,000 individuals would be required to pay these monthly premiums and that approximately 3% of these beneficiaries would lose eligibility due to failure to pay.

The Fallback Plan waiver would also add a premium surcharge for non-emergent use of the emergency department. The state seeks to require beneficiaries with incomes between 100% and 138% of the FPL to pay a $10 premium surcharge for any use of the emergency department considered non-emergent, up to a maximum of $30 per quarter. Individuals would receive one warning after the first occurrence of non-emergent emergency department use, and any subsequent non-emergent uses would result in the $10 surcharge to their monthly premium. An individual with five or more occurrences of non-emergent use within the most recent twelve months would be referred to the Medicaid Restriction Program, which could take additional action such as limitations on where the individual may receive services. Members of federally recognized tribes, individuals receiving employer-sponsored insurance reimbursement, and medically frail individuals would be exempt from this provision. The state estimates that between 1500 and 2000 beneficiaries would owe surcharges each month.

In addition to these provisions, the Fallback Plan waiver also seeks authority to make additional changes to the Medicaid expansion through the state administrative rulemaking process without requiring CMS approval. Utah expects that most of these changes, if enacted, would decrease total beneficiary months and demonstration expenditures. The changes include:

The Fallback Plan waiver is currently under consideration at CMS. Given CMS guidance about partial expansion, it seems clear that the request for enhanced ACA matching funds with an enrollment cap on the expansion group will not be approved, but CMS says it is reviewing the other requests. In its submission letter, Utah requested that CMS approve the Fallback Plan waiver by December 31, 2019, for implementation on January 1, 2020.

If CMS does not approve the Fallback Plan by July 1, 2020, Utah will adopt the full Medicaid expansion plan with no restrictions as set out by the ACA and approved in the ballot initiative. This plan would include coverage of all eligible adults up to 138% FPL at the ACA enhanced matching rate and would use a state plan amendment instead of waiver authority. It would not include a work requirement, enrollment cap, or other eligibility and enrollment restrictions as proposed in the waiver proposals described above.20

As the largest payer of substance use disorder services in the United States, Medicaid plays a central role in state efforts to address the opioid epidemic. In addition to increasing access to addiction treatment services through the expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), states are expanding Medicaid addiction treatment services, increasing provider reimbursements, restricting opioid prescribing, and implementing delivery system reforms to improve the quality of treatment services. While many states have been tracking progress and challenges in these efforts, uniqueness of state systems can make it difficult to compare or benchmark across states. This brief draws on analyses provided by the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network (MODRN), a collaborative effort to analyze data across multiple states to facilitate learning among Medicaid agencies. It profiles the opioid epidemic among the Medicaid population in six states participating in MODRN that also have been hard hit by the opioid epidemic: Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. The brief also draws on interviews with officials from the state Medicaid and other health agencies. Key findings include following:

The six states are taking other actions to improve access to and quality of addiction treatment services, such as recruiting and training more providers to prescribe buprenorphine, eliminating prior authorization requirements for buprenorphine, improving transitions between hospital settings and community-based care, and adopting new models of care delivery that emphasize greater coordination of MAT with other physical and behavioral health services. Most are also leveraging new federal funding through SAMHSA to work in concert with Medicaid reforms.

In the United States, Medicaid covers 38 percent of non-elderly adults with an opioid use disorder.1 As the largest payer of substance use disorder services in the United States, Medicaid plays a central role in state efforts to address the opioid epidemic, largely driving policy on improving delivery of treatment services.2 States may adopt several policy options to increase access to opioid use disorder treatment, improve quality of care and reduce overdose deaths among Medicaid enrollees, including expanding benefits to include a broader range of addiction treatments, increasing provider reimbursements, restricting opioid prescribing, and implementing delivery system reforms. While many states have been tracking progress and challenges in these efforts, uniqueness of state systems can make it difficult to compare or benchmark across states, and there is limited data to measure quality or outcomes of opioid treatment efforts. In addition, the expansion of Medicaid under the ACA extended eligibility to many people with substance use disorder who previously lacked access to affordable insurance coverage, but there is limited data on how expansion increased coverage and access to treatment services for opioid use disorder (OUD).

This brief draws on analyses provided by the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network (MODRN),3 a collaborative effort to analyze data across multiple states to facilitate learning among Medicaid agencies, to profile the opioid epidemic among the Medicaid population in six states – Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. All of these states participate in MODRN and include parts of Appalachia, a region hard hit by the opioid epidemic. MODRN data provides a snapshot of the opioid epidemic along several measures not available in public data. The brief focuses on adolescent and non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees (ages 12-64) who are not dually eligible for Medicare. As of the time of data collection, Virginia was the only state that had not expanded Medicaid under the ACA, though it has since done so. The brief also draws on interviews with officials from the state Medicaid and other health agencies and describes the major strategies and initiatives these six states are using to address the opioid epidemic among their Medicaid populations.

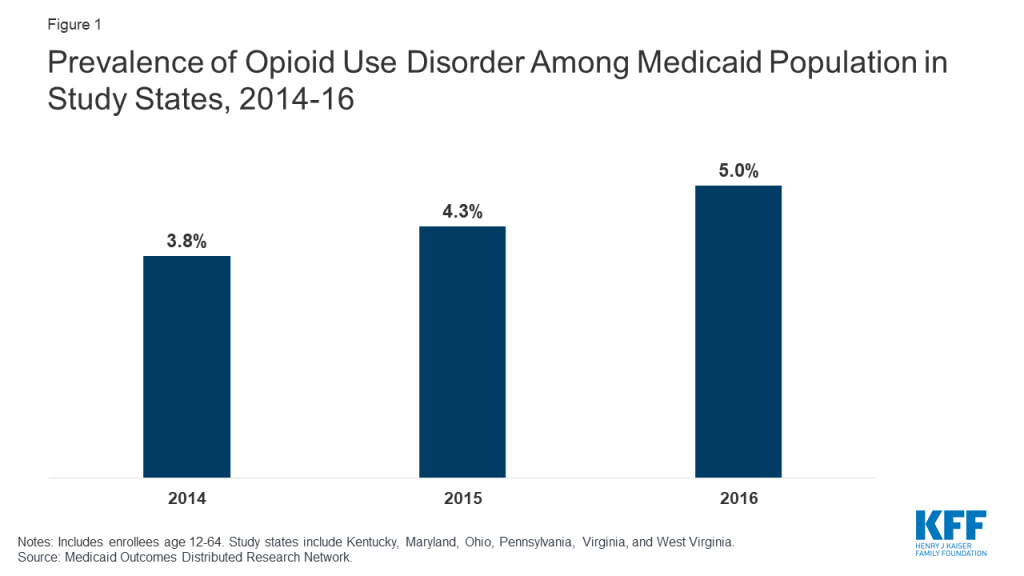

The prevalence of OUD among Medicaid enrollees in the study states is higher than the national average, reflecting regional concentration of the opioid epidemic within the United States. Among Medicaid enrollees ages 12-64 who are not dual Medicare/Medicaid eligible, the percent with a diagnosis of opioid use disorder increased from 3.8 percent in 2014 to 5.0 percent in 2016 in the six study states (Figure 1). This trend could reflect a true increase in prevalence, increased screening and diagnosis, or both. This prevalence compares to an estimated national average of <1% for people age 12-64 overall and 2% for Medicaid enrollees age 12-644 and reflects the fact that the study states include areas hardest hit by the opioid epidemic. States also noted that Medicaid covers a disproportionately large share of people with OUD in their states.

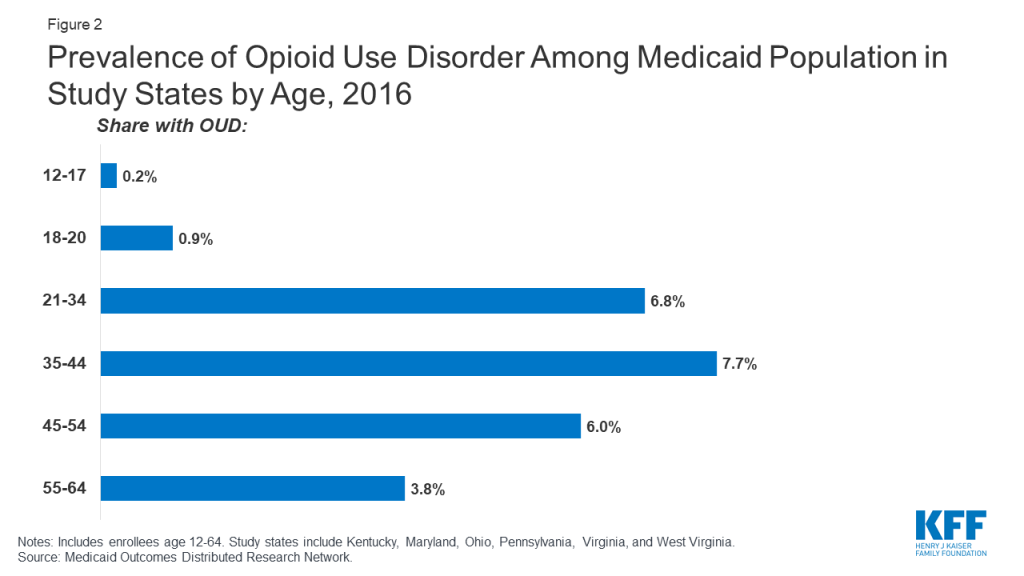

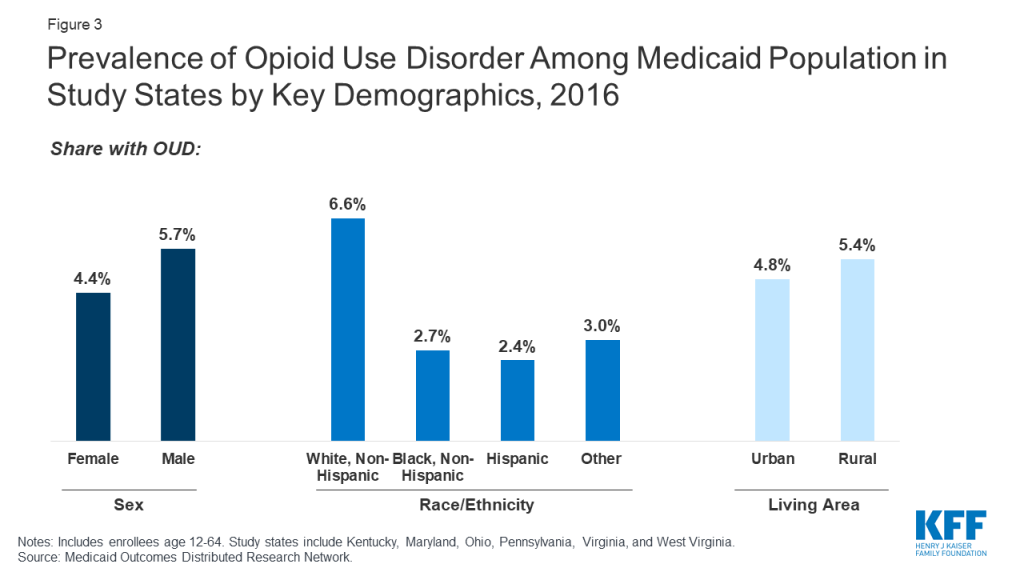

Across the study states, OUD prevalence is higher among working-age adults, males, and whites compared to other demographic groups. Among different age groups, enrollees aged 35-44 have the highest OUD prevalence at 7.7 percent, with children ages 12-17 having the lowest prevalence at less than 1 percent (Figure 2). Prevalence of OUD is higher among males compared to females (5.7 percent compared to 4.4 percent) and among Whites compared to African-Americans and Hispanics (6.6 percent compared to 2.7 percent and 2.4 percent) (Figure 3).

Though OUD prevalence is higher among Medicaid enrollees in rural areas, states report a growing problem in urban areas. A greater share of enrollees in rural areas have OUD compared to urban areas (5.4 percent compared to 4.8 percent, Figure 3). State respondents noted the social and economic distress in many rural communities and small towns in their state as one of the key drivers of the opioid epidemic, which may explain in part the higher prevalence among white, working age adults noted above. National data also show higher prevalence of OUD among low income, unemployed adults suffering from other psychosocial distress.5 However, respondents also stressed that OUD is also a growing problem for their urban populations. In fact, despite the higher prevalence in rural areas, in 2016, 74 percent of Medicaid enrollees with OUD lived in urban areas across the six states (findings not shown). Respondents in one state also noted differences in the nature of the opioid epidemic between urban and rural areas, with urban areas experiencing more of a problem with addiction to heroin, fentanyl, and other synthetic opioids, while prescription opioids were a greater contributor to the problem in rural areas.

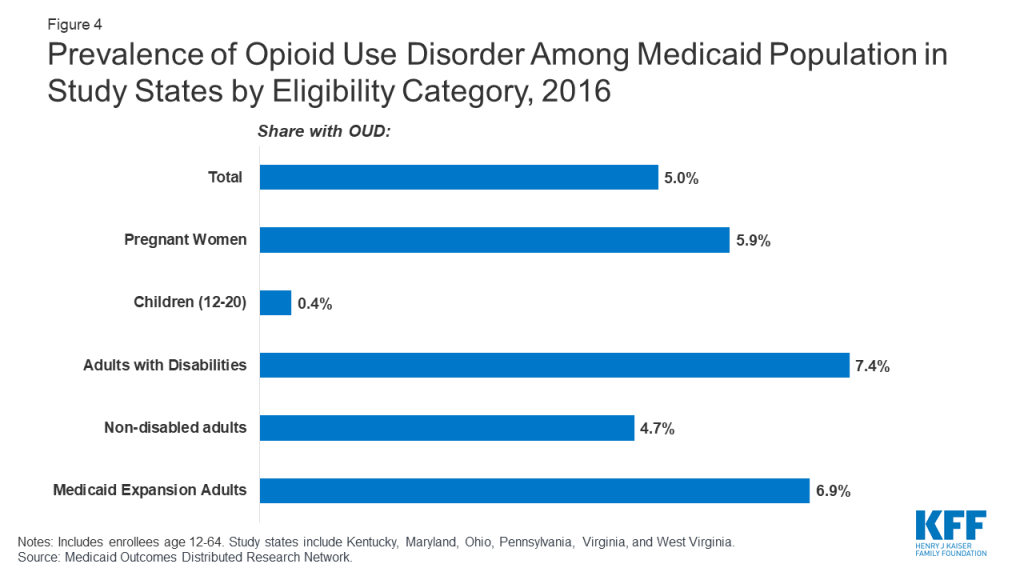

Though many Medicaid enrollees with OUD qualify through the ACA Medicaid expansion, prevalence of OUD among the Medicaid expansion population is similar to that for other eligibility groups. For the five out of six states that had expanded Medicaid prior to January 1, 2019, 6.9 percent of enrollees who qualified through Medicaid expansion had an OUD (Figure 4),6 and among all Medicaid enrollees with an OUD, 56 percent qualified through Medicaid expansion in 2016 (findings not shown). OUD prevalence among the Medicaid expansion population in the study states is slightly higher than other adults without disabilities (4.7%) and pregnant women (5.9%) and lower than prevalence among adults with disabilities (7.4%).

Reflecting eligibility criteria, the characteristics of enrollees with OUD who qualify through the ACA expansion differ from those who qualify for Medicaid through traditional eligibility pathways. Compared to enrollees with OUD who are eligible through pre-expansion criteria in the states that expanded Medicaid, the expansion population with OUD is disproportionately likely to be age 21-34 and male (Table 1), likely reflecting characteristics of adults who were ineligible for Medicaid under traditional pathways but gained eligibility under the ACA. State Medicaid officials also cite being a military veteran and having a history of employment in high-risk occupations (e.g. manufacturing, mining) as additional risk factors for OUD among the expansion population.7

| Table 1: Characteristics of Medicaid Enrollees with OUD in Study States by Eligibility Pathway, 2016 | ||

| Enrollees with OUD eligible through ACA expansion | Enrollees with OUD eligible through non-ACA pathway | |

| Age | ||

| % 12-17 | N/A | 1.5 |

| % 18-20 | 0 | 4.0 |

| % 21-34 | 51.1 | 43.8 |

| % 35-44 | 28.4 | 25.2 |

| % 45-54 | 15.3 | 14.9 |

| % 55-64 | 5.2 | 10.6 |

| – | ||

| Gender | ||

| % Female | 37.7 | 65.9 |

| % Male | 62.3 | 34.1 |

| — | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| % White | 81.3 | 79.3 |

| % African-American | 6.9 | 10.7 |

| % Hispanic | 3.1 | 3.3 |

| % Other | 8.7 | 6.7 |

| – | ||

| Living area | ||

| % Urban | 70.9 | 69.7 |

| % Rural | 28.6 | 30.0 |

| Living area missing/unknown | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| NOTES: Includes enrollees age 12-64. Estimates are pooled across four study states that had implemented ACA Medicaid expansion as of 2016 (KY, OH, PA, WV).SOURCE: Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network | ||

State policymakers view Medicaid expansion as an important tool for expanding access to OUD treatment by increasing coverage among populations with a high prevalence of OUD. Respondents in some states acknowledged concerns raised by some stakeholders about whether Medicaid expansion may have exacerbated the opioid addiction crisis by increasing access to opioid prescriptions, although it did not appear to be a major concern in any of the six states. Consistent with recent research, state officials maintain that not only have they not seen any evidence that Medicaid expansion exacerbated opioid addiction, but that in fact Medicaid was providing addiction treatment services for enrollees who previously had undiagnosed or unmet needs for these services or who were on high-dose opioids before they enrolled in Medicaid.8 States also reported that Medicaid expansion enabled them to expand the scope of services available to people with OUD, as Medicaid-covered benefits are broader than those available through state-funded programs for uninsured people.

In addition to increasing access to treatment through Medicaid expansion, most state Medicaid programs have also focused special attention on certain populations who are vulnerable to the effects of opioid addiction, such as pregnant women and newborns. For example, West Virginia established the first center in the United States to provide support services to newborns with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and their families. West Virginia’s Medicaid agency has established special rates to accommodate the specialized services provided by the center. Creating new data systems that can match a mother to her child within the Medicaid system has also been a priority as states frequently report lack of data as a barrier to measuring quality of care for pregnant women and infants.

All study states also report efforts to connect people in the criminal justice system to care. As studies show that more than half of the incarcerated population meet the criteria for drug dependence or abuse, state Medicaid agencies have also focused special attention on individuals released back to the community.9 All six states report taking measures to identify incarcerated individuals likely to be eligible for Medicaid and to get them started on treatment before or shortly after their release. For instance, Ohio’s pre-release program uses peer educators to enroll likely eligible prisoners into Medicaid prior to release.10 The program is intended to reduce the amount of time between release and accessing treatment, thereby reducing accidental overdoses.

Reflecting nationwide trends, all study states have efforts underway to limit access to prescribed opioids. In 2019, all states report using pharmacy benefit management strategies to prevent opioid-related harms.11 Similarly, all six states have taken steps to limit the quantity and dose of opioids prescribed to Medicaid enrollees, as well as requiring prior authorization for opioid prescribing for Medicaid patients.12 These steps include such actions as limiting days supplied and dosages (KY, PA, WV) and reducing the number of refills (OH). Ohio, Virginia and Pennsylvania have implemented the CDC guidelines for opioid prescribing in their Medicaid programs, which require prior authorizations to provide oversight of high dosage prescriptions and limit the number of days supplied. All states also report actions to more aggressively use Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), which track all prescriptions for opioids and other controlled substances in the state. Ohio and West Virginia are using PDMPs to identify clinics and other providers with excessive prescribing practices. States report that such measures have decreased opioid prescribing among Medicaid enrollees. In Virginia, for example, average days supplied for opioid prescriptions decreased 45 percent between 2016 and 2018, while the number of Medicaid enrollees receiving opioid prescriptions dropped by almost 30 percent.13

All six states now cover the full continuum of treatment services, based on the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) guidelines.14 Historically, coverage of addiction treatment services by Medicaid has varied considerably across the study states. Ohio and Pennsylvania provided the full continuum of outpatient, intensive outpatient, and residential treatment services based on ASAM guidelines since before 2016. Similarly, Maryland has covered most ASAM services, with exclusions for some Medicaid populations. While Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia have not been as comprehensive in their benefits historically, they have been closing the gap through recent expansions in services. In 2017, Virginia implemented the Addiction and Recovery Treatment Services (ARTS) program, which greatly expanded access to the full continuum of addiction treatment services, increased reimbursement rates for some existing services, and “carved” behavioral health services back into managed care plans in order to increase coordination with physical health services, and established a preferred provider model for OUD treatment. Kentucky and West Virginia have added coverage for methadone treatment and other services, such as Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), peer recovery services (WV), short-term residential services, and withdrawal management.

To facilitate expansion of residential treatment and inpatient detoxification services, five of the six states have received Section 1115 waivers and report that these waivers are crucial in allowing them to provide the full continuum of treatment services. As of October 2019, 26 states have Section 1115 waivers to use federal Medicaid funds for residential facilities of 16 beds or greater, otherwise prohibited through Medicaid’s Institutions for Mental Diseases (IMD) exclusion.15 Waivers have enabled states to provide treatment services based on ASAM treatment guidelines, specifically for short-term residential treatment services (ASAM Level 3) and medically managed intensive inpatient services (ASAM Level 4). However, there is some concern that reversing the IMD exclusion through waivers could lead to greater reliance on more costly institutional care for the treatment of substance use disorders and possibly prolonged institutional stays for people who could be adequately served in the community. Further, some note that the focus on institutional care without commensurate focus on community-based care may interfere with states’ ability to meet community integration requirements under the Americans with Disabilities Act. For states that had implemented waivers at the time of the study, it was too soon to assess impact. However, analysis of the first year of Virginia’s ARTS program showed that most treatment was provided in outpatient settings. Of the 9,700 Medicaid members who used any ASAM service, only about 200 used residential treatment services (ASAM level 3), while more than 500 used medically managed intensive inpatient services (ASAM 4). By contrast, almost 7,000 members with OUD used outpatient services (ASAM Level 1).16

Reflecting nationwide trends, all six study states cover medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for OUD, which is considered the “gold standard” for opioid use disorder treatment.17 MAT includes pharmacotherapy along with psychotherapy and social support. The most common medications used in MAT are methadone and buprenorphine, which is sold either alone or in combination with naloxone (as Suboxone).18 Extended-release injectable naltrexone is also approved by the FDA for treatment of opioid use disorder. Nationally, 44 states cover MAT.19 All six study states have elected to cover buprenorphine, as well as naltrexone and methadone treatment (Kentucky will add methadone coverage when its Section 1115 waiver is implemented).

Less than half of Medicaid enrollees with OUD receive any MAT. All six states have implemented measures to support use of MAT within the Medicaid program and have experienced increased rates of MAT use since 2014. However, use of MAT among individuals diagnosed with an OUD remains low at only 48 percent across the six states in this study (Table 2). Even these estimates of treatment among those diagnosed with OUD may overstate treatment rates, since many individuals with OUD go undiagnosed. For example, based on national survey data among those with prescription opioid use disorder, only 17.5 percent report receiving any treatment for it.20

Treatment rates vary by demographic and eligibility group. Among those with diagnosed OUD in the six states in 2016, MAT rates are highest among those in the 21-44 age group, among women, among whites, and slightly higher among those living in urban compared to rural areas (Table 2). Comparing enrollees based on eligibility pathway, MAT rates are highest for traditionally eligible, non-disabled adults (56.2 percent) and pregnant women with OUD (53.6 percent), lower for Medicaid expansion adults (48.1 percent) and people qualifying based on a disability (40.0 percent) and significantly lower for people qualifying as children (including adolescents or young adults) (19.2 percent).

| Table 2: Medication-assisted treatment (in 2016) and continuity of pharmacotherapy for OUD (in 2015-2016) by demographic group | ||

| Percent with OUD who receive Medication-Assisted Treatment | Percent who had continuity of pharmacotherapy treatment | |

| Overall | 48.2% | 52.4% |

| Age | ||

| 12-171 | 2.9 | N/A |

| 18-20 | 26.1 | 31.1 |

| 21-34 | 51.5 | 48.4 |

| 35-44 | 52.1 | 54.4 |

| 45-54 | 43.4 | 61.4 |

| 55-64 | 34.9 | 66.7 |

| – | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 49.7 | 55.0 |

| Male | 46.7 | 49.6 |

| – | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 50.4 | 51.4 |

| African-American | 40.7 | 62.2 |

| Hispanic | 39.3 | 54.8 |

| Other | 42.1 | 46.8 |

| – | ||

| Living area | ||

| Urban | 48.5 | 54.0 |

| Rural | 47.2 | 47.8 |

| Eligibility status | ||

| Pregnant women | 53.6 | 52.9 |

| Adolescents/young adults1 | 19.2 | 26.8 |

| Adults with disabilities | 40.0 | 60.3 |

| Adults without disabilities | 56.2 | 57.2 |

| Medicaid expansion adults | 48.1 | 47.5 |

| NOTES: Includes enrollees age 12-64. Estimates pooled across six study states.1 Percent with medication-assisted treatment measure includes adolescents and young adults aged 12-20 in 2016. The percent who had continuity of pharmacotherapy only includes young adults aged 18-20 per the NQF specifications and the time period is 2015-2016.SOURCE: Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network | ||

In addition, many enrollees receiving MAT are not retained in continuous treatment. The duration of MAT is associated with health outcomes including recovery. Although the amount of time on MAT needed for recovery varies from patient to patient, in general, longer treatment periods result in better outcomes and reduce the risk of relapse. Among Medicaid enrollees in the six states receiving pharmacotherapy for OUD, 52% received at least six months of treatment (Figure 5). Among those receiving pharmacotherapy, enrollees in the 55-64 age group were more likely to have continuous treatment for six months compared to younger age groups (Table 2). Females, African-Americans, and those living in urban areas also had greater continuity of treatment compared to other subpopulations. Continuity was highest among people qualifying based on a disability (61 percent) and lowest among the child/young adult population (18-20 years) (26 percent) (Table 2).

Most (five of six) states report an under-supply of prescribers as a major barrier to increasing MAT for Medicaid enrollees. Historically, pharmacotherapy for treatment of OUD was restricted to methadone delivered by opioid treatment programs (OTPs) accredited by SAMHSA or other approved accrediting bodies. To increase access to MAT, the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) allowed qualified physicians to dispense or prescribe buprenorphine if they completed eight hours of training and applied for and received a waiver from SAMHSA. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 allows nurse practitioners and physician assistants to also receive waivers and prescribe buprenorphine, which Maryland officials cited as significantly increasing the supply of prescribers in that state. While the number of buprenorphine waivered prescribers has increased nationally and across the six states, all states except West Virginia reported provider supply issues. As with other health services, some states reported challenges in enlisting prescribers to accept Medicaid patients. Rates of buprenorphine prescriber participation in Medicaid are likely to be comparable to Medicaid provider participation more broadly, in which acceptance of new Medicaid patients is much higher among primary care physicians (70 percent) compared to psychiatrists (36 percent).21

Recruiting and training more providers to become buprenorphine prescribers and to increase their patient capacity is a high priority in most of the states. For example, Ohio has taken advantage of grant funding through the 21st Century Cures Act to train physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants to apply for waivers and provide MAT. While much of the focus is on recruiting primary care providers to become prescribers, some states are also focusing on recruiting more OB/GYNs to become prescribers to increase treatment for pregnant women. Most of the states have also implemented or are planning to increase use of telemedicine in MAT, such as through Project ECHO programs that link primary care practices to specialists in academic settings who provide mentoring and feedback in order to increase access in rural or other underserved areas.22

Other barriers to MAT access and continuity cited by state officials include challenges in transitioning patients from one level of care to another and stigma or resistance to MAT. States are focusing on transitioning patients into treatment after acute care hospital stays and emergency departments. Both Kentucky and Pennsylvania have initiatives to encourage health systems to initiate treatment in the hospital setting and connect patients to community providers for ongoing treatment and support. In addition, policymakers noted stigma or resistance not only among patients, but also among some providers, policymakers, law enforcement, and others in the recovery community who object to using opioid-based medications to treat OUD, and prefer abstinence-only and counseling approaches to treatment that have been shown to be less effective than MAT.

States are developing policies to balance increased access to MAT and prevention of misuse. Because MAT treatments are opioid-based, they can be diverted, misused, and sold illegally. Respondents in all six states report current or past problems with “cash clinics,” in which patients pay physicians out-of-pocket for the cost of the visit to receive buprenorphine prescriptions, with little assurance that appropriate care guidelines are followed or that individuals are prevented from diverting prescriptions into the community. At the same time, most state respondents noted that overly restrictive policies on buprenorphine prescribing – such as stringent prior authorization requirements – can inhibit access to these effective medications for patients. Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia have recently loosened prior authorization programs to encourage providers to deliver buprenorphine and reduce provider supply-related barriers to treatment access. For example, Virginia has eliminated prior authorizations for certain “preferred” providers, and Pennsylvania has required its managed care organizations to make at least one OUD medication be available on a preferred drug list without prior authorization. In contrast, West Virginia continues to carefully regulate providers authorized to prescribe buprenorphine, such as requiring additional documentation of past disciplinary actions and monitoring of compliance with requirements for urine drug screens and counseling.

Most study states are adopting new models of care delivery for OUD. Realizing that navigating the continuum of addiction treatment services is complex, and merely covering MAT treatment will not necessarily lead to improved outcomes, most of the states are adopting new models of care delivery that emphasize evidence-based MAT treatment, coordination with the different levels of treatment, and integration with other physical and behavioral health services. For example, Pennsylvania established a Centers of Excellence program based on a “hub and spoke” model of treatment in 2016, in which the centers serve as the “hub” that provide the most intensive treatment services, while connecting patients with other services necessary for maintaining and managing their treatment over the longer term. State officials attribute a substantial increase in treatment rates to the Centers of Excellence. West Virginia is in the process of establishing a similar model, the Comprehensive Opioid Addiction Treatment (COAT) clinic. A second model is the preferred provider, as seen in Virginia’s Preferred Opioid-Based Opioid Treatment (OBOT) program. These providers, credentialed by the Medicaid program, have co-located buprenorphine-certified providers and behavioral health specialists. As preferred providers, they receive increased reimbursement to conduct care coordination activities and comprehensive services. A third model, used by Maryland and Ohio, is the medical home. While not OUD-specific, these medical homes are intended to provide or coordinate all physical health and behavioral health needs.

Most states have not yet adopted alternative payment models for OUD treatment services. While some of these new care delivery models include incentivizing providers to achieve better outcomes, use of alternative payment approaches for addiction treatment is still in the discussion phase for most states. Pennsylvania may be furthest along the path, having used bundled payment arrangements for methadone treatment for many years.

All six states are working to build the long-term infrastructure for collecting data and developing measures of quality to monitor outcomes. In some states, these include data linkages between Medicaid, Department of Corrections, Emergency Medical Services, prescription drug monitoring programs, mortality, and birth records to provide more timely and comprehensive monitoring of the opioid epidemic.

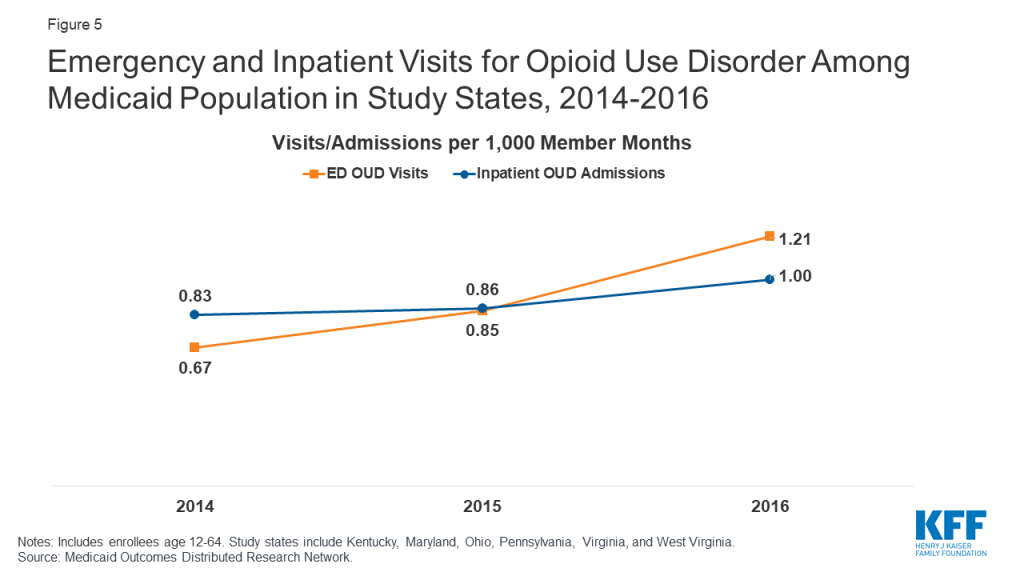

Most states were still seeing indications of a growing opioid epidemic through 2016. States use a variety of methods to measure treatment outcomes and the effects of treatment and state policies designed to increase access to and quality of treatment. While a widely-cited measure is overdose fatalities, this outcome represents only a small fraction of those afflicted with opioid use disorders. Other measures, such as opioid-related emergency department visits and acute inpatient stays, may reflect broader prevalence and access trends. As shown in Figure 5, the rate of ED visits for OUD nearly doubled between 2014 and 2016 among enrollees in the six states from 0.67 to 1.21 per 1,000 member months. The rate of inpatient admissions for OUD increased less sharply from 0.83 to 1.00 between 2014 and 2016. Among Medicaid enrollees, rates of ED and acute inpatient use for OUD tend to be higher among adults ages 21-44, males, whites, and residents of urban areas compared to other subpopulations (Table 3). Among Medicaid eligibility categories, OUD-related ED and inpatient use is highest among Medicaid expansion enrollees, pregnant women, and adults with disabilities and lowest among adolescents and young adults and traditionally eligible, non-disabled adults.

| Table 3: Rates of OUD-related ED visits and inpatient stays among Medicaid enrollees, by demographic characteristics, 2016 | ||

| OUD-related ED visits per 1,000 member months | OUD-related inpatient admissions per 1,000 member months | |

| Total | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Age | ||

| 12-17 | 0.1 | <0.05 |

| 18-20 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 21-34 | 2.0 | 1.4 |

| 35-44 | 1.8 | 1.4 |

| 45-54 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 55-64 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| – | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Male | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| – | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| African-American | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Hispanic | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Other | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| – | ||

| Eligibility group | ||

| Pregnant women | 1.5 | 2.7 |

| Adolescents and young adults (12-20) | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Adults with disabilities | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| Adults without disabilities | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Medicaid expansion adults | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| – | ||

| Living area | ||

| Urban | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Rural | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| SOURCE: Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network | ||

Medicaid programs are central to state efforts to address the opioid epidemic, in part due to the high prevalence of OUD among low-income populations eligible for Medicaid. Leaders in Medicaid agencies in all six study states viewed Medicaid expansion as important in expanding coverage to individuals with OUD to reduce financial barriers to treatment. State Medicaid programs also have a number of tools that can be used to leverage state and federal resources, such as by expanding coverage for the full range of treatment options, increasing reimbursement to attract more providers, developing new care delivery models, and seeking Section 1115 Demonstration Waivers that allow federal Medicaid payments for residential treatment. In addition, the federal SUPPORT Act allows for or mandates Medicaid services to treat OUD, puts in place protections for some eligibility groups to maintain Medicaid coverage, requires prescription drug oversight and quality reporting related to Medicaid and OUD, and authorizes new demonstrations to address provider capacity constraints and transitions from the criminal justice system, among other provisions.23 This new federal law will likely expand Medicaid’s role in addressing OUD as states take up new options, implement demonstrations, or comply with federal requirements.

State Medicaid reforms are also integral to coordinated state strategies to address the opioid addiction crisis, especially in terms of aligning Medicaid restrictions on opioid prescribing with more general state and restrictions. Because effectively addressing opioid addiction overlaps with medical, public health, criminal justice, and social welfare sectors, state agencies are actively working with other state agencies on a coordinated response to the epidemic. The Kentucky Opioid Response Effort (KORE) is an example of a multi-agency effort to provide a comprehensive response to the opioid epidemic in the state, and provide grants to expand services. Other states have set up inter-agency task forces – a few of which are led by the state’s Medicaid agency — that meet on a regular basis to coordinate strategies and address issues related to treatment, housing, employment, and other social needs.

Many of these states have also leveraged new funding through SAMHSA, such as State Targeted Response (STR) and the newer State Opioid Response (SOR) grants to work in concert with Medicaid reforms to increase supply and availability of treatment providers, encourage and train more providers to become MAT prescribers, build crisis stabilization centers as an alternative to ERs and jails, conducting patient outreach and education to encourage them to begin and stay in treatment, and to reduce the stigma associated with MAT. State Medicaid agencies pointed to the need for long-term, coordinated strategies to improve systems of care to address not only the opioid crisis but other behavioral health needs among low-income, vulnerable populations.

Julie Donohue is Professor, Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health. Peter Cunningham is Professor, Department of Health Behavior and Policy, Virginia Commonwealth University. Lauryn Walker was a Research Assistant at the Department of Health Behavior and Policy, Virginia Commonwealth University at the time of this project. Rachel Garfield is a Vice President at KFF and Co-Director of its Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

Data in this brief is from the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network (MODRN), an initiative of AcademyHealth.24 MODRN is a collaborative effort to analyze data across multiple states to facilitate learning among Medicaid agencies. Participants from AcademyHealth’s State-University Partnership Learning Network (SUPLN) and the Medicaid Medical Director Network (MMDN) developed MODRN to allow states to participate in multi-state data analyses while retaining their own data and analytic capacity.

MODRN is composed of multiple organizations using a common data model to support centralized development, but local execution, of analytic programs. Under MODRN, each state-university partnership adopts the Medicaid Common Data Model, contributes to a common analytic plan, and conducts analyses locally on their own Medicaid data using standardized code developed by the data coordinating center. Finally, the state-university partners provide aggregate results, not data, to the data coordinating center, which synthesizes the aggregate findings from multiple states for reporting. The Medicaid Common Data Model will be continually updated and expanded for future Medicaid research projects.

Eleven university-state partnerships now participate in an effort to provide a comprehensive assessment of opioid use disorder treatment quality in Medicaid. The findings presented in this report resulted from that project that at the time of this writing had been implemented by six university participants include the University of Kentucky, University of Maryland Baltimore County, The Ohio State University, University of Pittsburgh, Virginia Commonwealth University, and West Virginia University.

Below we detail the construction of the variables used in the data analysis across the six study states.

The data analysis covered years 2014 through 2016. Some measures pool data across two-year period per National Quality Forum Specifications.

This analysis includes non-dual, full-benefit Medicaid enrollees age 12-6425 with at least one month of Medicaid eligibility in the calendar year.

For analysis by eligibility category, we group enrollees into categories using the following hierarchy:

We identify people with OUD based on diagnosis codes in claims. Specifically, we identify those who had at least one encounter with any diagnosis (counting all diagnosis fields) of OUD in inpatient, outpatient, or professional claims at any time during the measurement period. We used National Quality Forum code sets to identify diagnosis codes for measuring OUD.26

After identifying the population with OUD as detailed above, we calculate utilization rates for MAT by identifying individuals with OUD who have at least one claim for medication-assisted treatment for OUD. Specifically, we include those who have at least one claim with a National Drug Code (NDC) or a HCPCS code for any of the following OUD medications during the measurement period:

We excluded claims for oral medications with negative, missing, or zero days’ supply.

This measure is calculated for three rolling two-year periods from 2014 to 2016: 2014-2015, and 2015-2016, to allow for 180-day measurement of pharmacotherapy for enrollees whose treatment episodes span calendar years. For each two-year period, we limit the analysis to individuals who (1) had a diagnosis of OUD, as described above27 (2) had at least one claim for an OUD medication, as described above, and (3) who are 18-63 years of age28 for the duration of the first year during which they appear in the period. We only include individuals who received oral OUD medications during the two-year period with a date at least 180 days before the end of the final calendar year of the measurement period. Further, we only include individuals who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid for at least 6 months after the month with the first OUD medication claim in the measurement period, with no gap in enrollment. Individuals who are not enrolled for 6 months, including those who die during the period, are not eligible and are not included in this part of the analysis.

Within this group, we measure continuity of treatment by identifying individuals who have at least 180 days of continuous pharmacotherapy with a medication prescribed for OUD without a gap of more than seven days. We developed a set of decision rules for counting surplus for overlaps among prescription claims and for counting length of days for medications with different administration (e.g., prescription OUD medications, Naltrexone injections, and for licensed treatment center-dispensed methadone and office-dispensed buprenorphine/naloxone).29

We measure emergency department (ED) visits for OUD as distinct ED visits with OUD diagnosis in any diagnosis field. For each enrollee, we consider a distinct combination of billing provider ID and date of service as a distinct ED visit. Similarly, we measure distinct inpatient hospitalization episodes with OUD diagnosis in any diagnosis field. We exclude detoxification and partial hospitalization and count direct transfers from one facility to another (discharge from one inpatient setting and admission to a second inpatient setting within one calendar day or less) as a single hospitalization.

To facilitate comparison of ED visit and inpatient hospitalization rates, we calculate visits/admissions per 1,000 member-months in the time period.

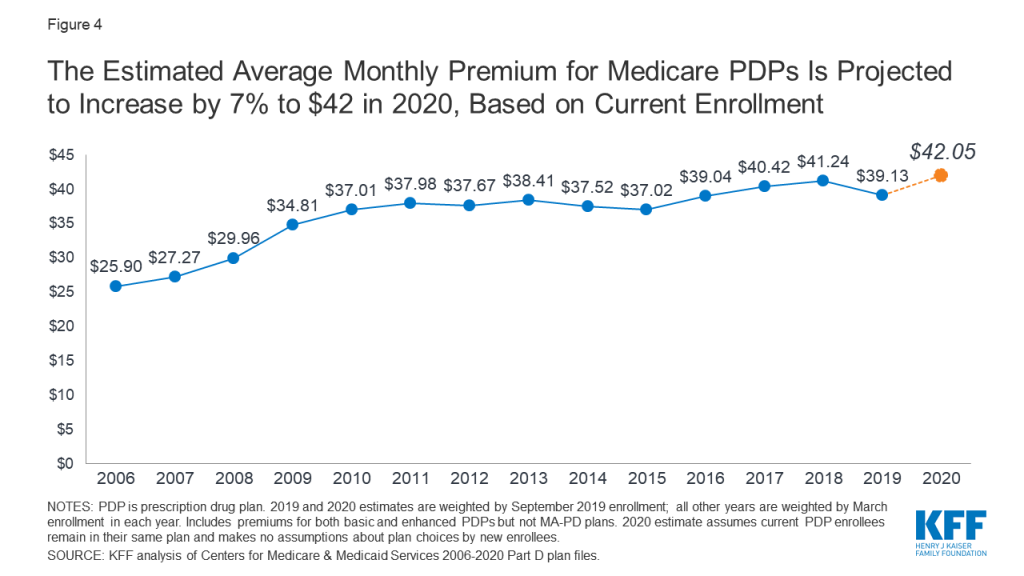

Millions of current enrollees in stand-alone Medicare Part D prescription drug plans will face premium and other cost increases next year unless they switch to lower-cost plans during the open enrollment period that began Oct. 15 and ends on Dec. 7, a new KFF analysis finds.

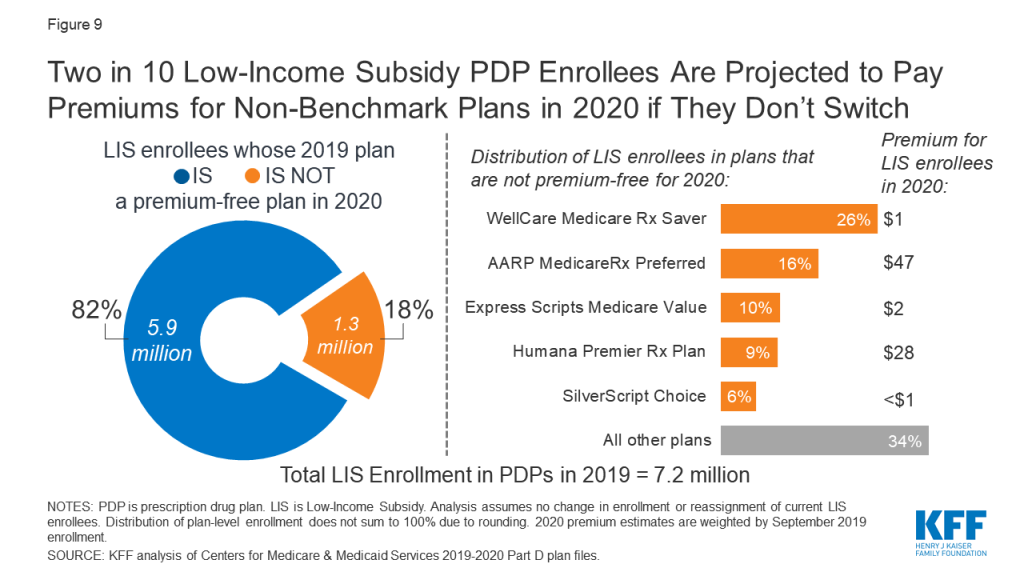

This includes two-thirds of Part D stand-alone drug plan enrollees not receiving low-income subsidies—nine million enrollees—who will face higher monthly premiums if they keep their current plan in 2020.

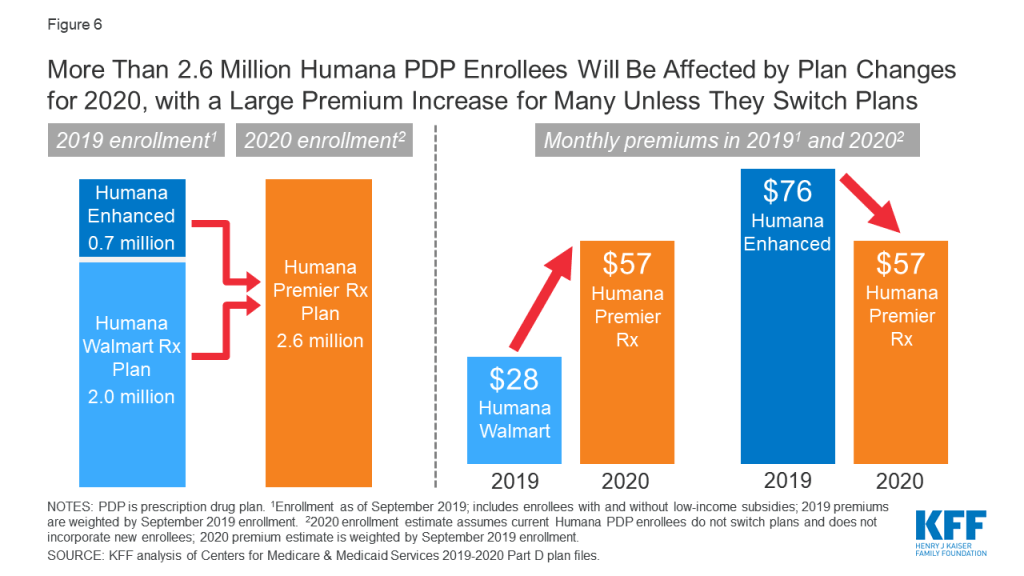

For instance, the 1.9 million enrollees without low-income subsidies in the Humana Walmart Rx plan—the third most popular stand-alone plan in 2019—will see their monthly premium more than double, on average, if they do not switch plans for 2020. That is because Humana is consolidating this plan and the Humana Enhanced plan into a new offering named Humana Premier Rx. Current Humana Walmart Rx enrollees will be automatically enrolled in the new plan, and, unless they switch, will see their monthly premium rise from $28 to $57.

While premiums for some other national plans are decreasing, enrollees in those plans may face other cost increases. For example, the 2.1 million enrollees without low-income subsidies in the nation’s largest stand-alone Part D plan, CVS Health’s SilverScript Choice, will see a modest $2 decrease in their average monthly premium, from $31 in 2019 to $29 in 2020. But the annual deductible in this plan will increase from $0 in most areas in 2019 to $215 to $435 in 2020—an increase that will more than offset the modest $2 monthly premium reduction.

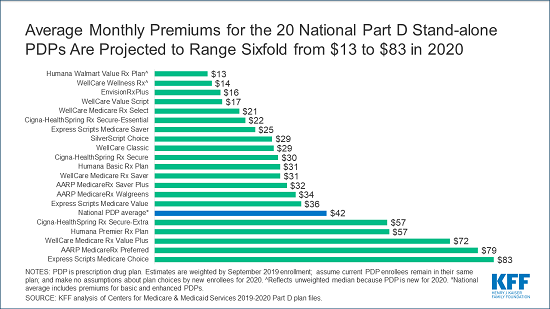

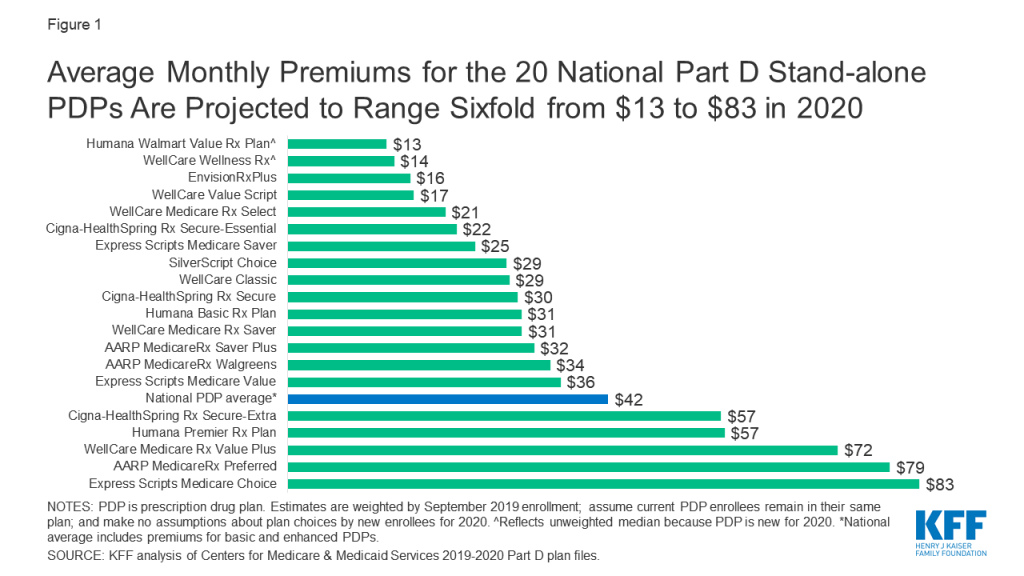

Overall, the analysis finds that premiums will vary widely across plans in 2020, as in previous years. Among the 20 stand-alone Part D plans available nationwide, average premiums will range sixfold, with the two lowest-premium plans charging $13 per month (Humana Walmart Value Rx) and $14 per month (WellCare Wellness Rx) and the two highest-premium plans charging $79 per month (AARP MedicareRx Preferred) and $83 per month (Express Scripts Medicare Choice). The estimated national average monthly PDP premium for 2020 is projected to increase by 7% to $42, based on current enrollment patterns. The actual national average premium in 2020 may be lower if current enrollees switch to, and new enrollees choose, lower-premium plans during open enrollment.

Among other key findings in Medicare Part D: A First Look at Prescription Drug Plans in 2020:

Forty-five million beneficiaries have prescription drug coverage through Medicare, including 20.6 million who are in stand-alone Part D plans as a supplement to traditional Medicare. The analysis provides an overview of stand-alone plans that will be available in 2020 and highlights key changes from prior years.

The analysis does not cover the 17.4 million people enrolled in Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans (non-employer) and another 4.6 million enrollees in employer-group only stand-alone plans and 2.3 million in employer-group only Medicare Advantage drug plans. Premiums and benefits data for these employer-group plans are not publicly available.

Also available are KFF’s newly updated basic resource, An Overview of the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit, and the recently released How Will The Medicare Part D Benefit Change Under Current Law and Leading Proposals?, which shows that some Part D enrollees can expect to see their out-of-pocket drug expenses rise in 2020.

During the Medicare open enrollment period from October 15 to December 7 each year, beneficiaries can enroll in a plan that provides Part D drug coverage, either a stand-alone prescription drug plan (PDP) as a supplement to traditional Medicare, or a Medicare Advantage prescription drug plan (MA-PD), which covers all Medicare benefits, including drugs. Among the 45 million Part D enrollees in 2019, 20.6 million (46%) are in PDPs (excluding employer-only group PDPs). This issue brief provides an overview of PDPs that will be available in 2020 and highlights key changes from prior years.

A larger number of Part D plans will be offered in 2020 than in recent years.

.Premiums

The estimated national average monthly PDP premium is expected to increase by 7% to $42 in 2020.

PDP premiums will continue to vary widely across plans in 2020, as in previous years.

Changes to premiums from 2019 to 2020, averaged across regions and weighted by September 2019 enrollment, also vary widely across PDPs, as do the absolute amounts of monthly premiums for 2020.

Average PDP monthly premiums for 2020 will vary across the 34 PDP regions, from $33 in Hawaii to $49 in New Jersey (see map; Table 1).

.

In 2020, all PDPs will offer an alternative benefit design, different from the defined standard benefit, which has a $435 deductible (an increase from $415 in 2019) and 25% coinsurance for all covered drugs between the deductible and the initial coverage limit. Part D plans can also provide enhanced benefits, including a lower (or no) deductible, reduced cost sharing, and/or a higher initial coverage limit than under the standard benefit design.

In 2020, all PDPs will have a benefit design with five or six tiers for covered generic, brand-name, and specialty drugs and cost sharing other than the standard 25% coinsurance. As of 2020, Part D enrollees will no longer be exposed to a coverage gap, sometimes called the “doughnut hole,” when they fill their prescriptions; coinsurance in the coverage gap phase will be 25% for both brands and generics.

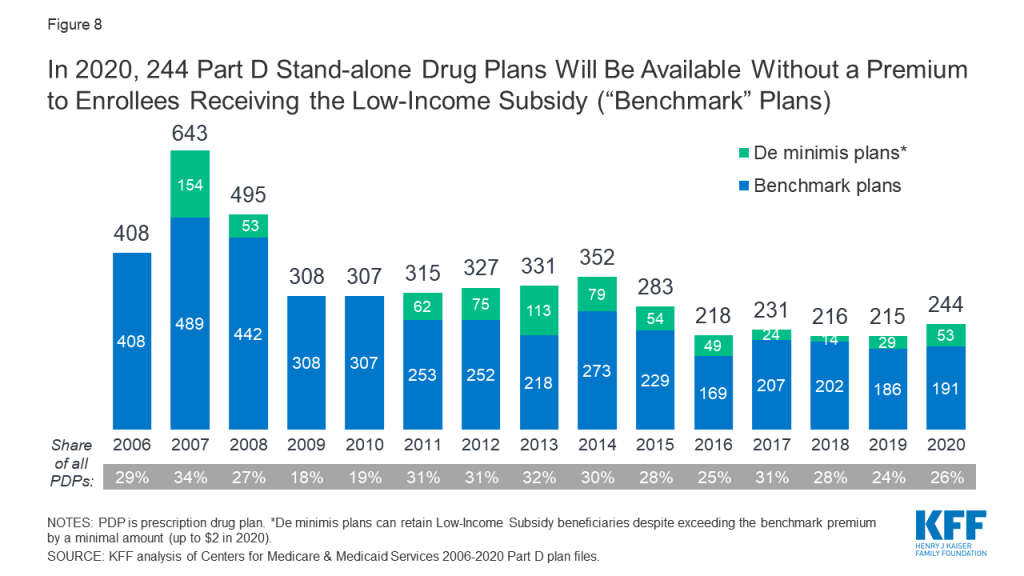

In 2020, a larger number of PDPs will be premium-free benchmark plans—that is, PDPs available for no monthly premium to beneficiaries receiving the Low-Income Subsidy (LIS)—than in recent years.

.

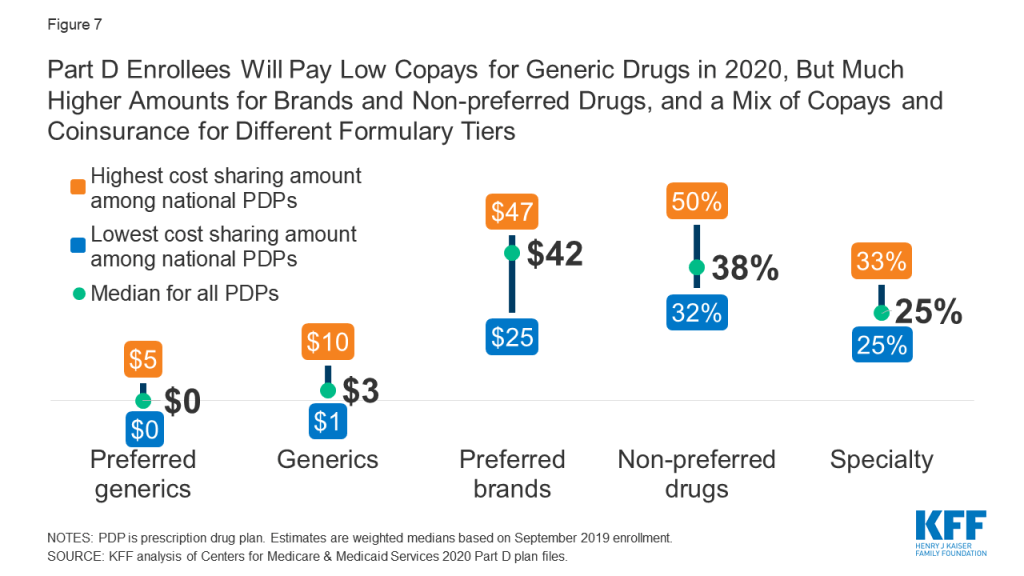

Our analysis of the Medicare Part D stand-alone drug plan landscape for 2020 shows that millions of Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies will face premium and other cost increases in 2020 if they stay in their current stand-alone drug plan. There are more plans available nationwide in 2020, with Medicare beneficiaries having nearly 30 PDP choices during this year’s open enrollment period. Most Part D enrollees will be in a plan with the standard $435 deductible and will face low copayments for generic drugs but substantially higher costs for brands, including as much as 50% coinsurance for non-preferred drugs.

Some Part D enrollees who choose to stay in their current plans may see lower premiums and other costs for their drug coverage, but two-thirds of non-LIS enrollees will face higher premiums if they remain in their current plan, and many will also face higher deductibles and cost sharing. As in prior years, all Part D enrollees could benefit from the opportunity to compare plans during open enrollment, since plans vary in a number of ways that can have a significant effect on an enrollee’s out-of-pocket spending.

| Juliette Cubanski and Tricia Neuman are with KFF.Anthony Damico is an independent consultant. |

Methods

This analysis focuses on the Medicare Part D stand-alone prescription drug plan marketplace in 2020 and trends over time. The analysis includes 20.5 million enrollees in stand-alone PDPs, as of September 2019. The analysis excludes 17.4 million MA-PD enrollees (non-employer), and another 4.6 million enrollees in employer-group only PDPs and 2.3 million in employer-group only MA-PDs for whom plan premium and benefits data are unavailable (as of March 2019).

Data on Part D plan availability, enrollment, and premiums were collected from a set of data files released by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS):

– Part D plan landscape files, released each fall prior to the annual enrollment period

– Part D plan and premium files, released each fall

– Part D plan crosswalk files, released each fall

– Part D contract/plan/state/county level enrollment files, released on a monthly basis

– Part D Low-Income Subsidy enrollment files, released once annually

– Medicare plan benefit package files, released each fall

– Medicare penetration files, released on a monthly basis

In this analysis, premium estimates are weighted by September 2019 enrollment unless otherwise noted. Percentage increases are calculated based on non-rounded estimates and in some cases differ from percentage calculations calculated based on rounded estimates presented in the text.

| Table 1: Medicare Part D Stand-alone Prescription Drug Plans, Benchmark Plans, and Monthly Premiums, 2019 and 2020 | ||||||

| Number of PDPs | Number of Benchmark PDPs | Weighted Average PDP Monthly Premium | ||||

| State/territory | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 |

| U.S. Total | 901 | 948 | 215 | 244 | $39.13 | $42.05 |

| Alabama | 29 | 30 | 6 | 7 | $41.65 | $44.55 |

| Alaska | 22 | 24 | 7 | 7 | $36.94 | $38.93 |

| Arizona | 28 | 31 | 10 | 12 | $38.29 | $42.77 |

| Arkansas | 26 | 27 | 4 | 6 | $34.30 | $37.49 |

| California | 30 | 32 | 7 | 8 | $43.50 | $43.20 |

| Colorado | 26 | 26 | 7 | 7 | $38.38 | $42.36 |

| Connecticut | 26 | 25 | 7 | 7 | $42.27 | $44.78 |

| Delaware | 25 | 27 | 9 | 10 | $39.33 | $43.32 |

| District of Columbia | 25 | 27 | 9 | 10 | $35.09 | $36.37 |

| Florida | 27 | 27 | 2 | 4 | $42.45 | $45.72 |

| Georgia | 26 | 28 | 4 | 6 | $36.77 | $38.59 |

| Hawaii | 24 | 25 | 4 | 5 | $32.15 | $33.97 |

| Idaho | 26 | 28 | 8 | 8 | $37.92 | $42.37 |

| Illinois | 27 | 28 | 7 | 8 | $39.01 | $42.30 |

| Indiana | 26 | 28 | 7 | 7 | $37.17 | $40.33 |

| Iowa | 28 | 29 | 6 | 8 | $34.36 | $39.49 |

| Kansas | 26 | 28 | 4 | 6 | $38.33 | $39.51 |

| Kentucky | 26 | 28 | 7 | 7 | $37.32 | $39.33 |

| Louisiana | 26 | 26 | 8 | 9 | $37.26 | $39.50 |

| Maine | 26 | 26 | 7 | 6 | $39.46 | $40.12 |

| Maryland | 25 | 27 | 9 | 10 | $37.75 | $40.96 |

| Massachusetts | 26 | 25 | 7 | 7 | $39.95 | $42.37 |

| Michigan | 29 | 30 | 9 | 9 | $37.18 | $39.93 |

| Minnesota | 28 | 29 | 6 | 8 | $34.98 | $39.75 |

| Mississippi | 24 | 25 | 5 | 7 | $34.46 | $36.05 |

| Missouri | 26 | 28 | 4 | 5 | $38.30 | $41.33 |

| Montana | 28 | 29 | 6 | 8 | $35.73 | $40.50 |

| Nebraska | 28 | 29 | 6 | 8 | $34.08 | $38.76 |

| Nevada | 26 | 28 | 3 | 5 | $36.63 | $40.38 |

| New Hampshire | 26 | 26 | 7 | 6 | $38.56 | $40.76 |

| New Jersey | 26 | 28 | 6 | 8 | $43.82 | $49.10 |

| New Mexico | 27 | 26 | 7 | 7 | $33.15 | $36.15 |

| New York | 23 | 27 | 8 | 9 | $44.13 | $47.84 |

| North Carolina | 28 | 28 | 7 | 9 | $38.97 | $41.82 |

| North Dakota | 28 | 29 | 6 | 8 | $34.37 | $37.84 |

| Ohio | 26 | 28 | 7 | 2 | $37.68 | $41.43 |

| Oklahoma | 28 | 29 | 7 | 8 | $40.43 | $41.58 |

| Oregon | 26 | 28 | 7 | 8 | $35.64 | $38.80 |

| Pennsylvania | 30 | 31 | 9 | 10 | $38.94 | $42.23 |

| Rhode Island | 26 | 25 | 7 | 7 | $39.21 | $42.57 |

| South Carolina | 26 | 28 | 3 | 5 | $36.63 | $42.85 |

| South Dakota | 28 | 29 | 6 | 8 | $33.70 | $39.65 |

| Tennessee | 29 | 30 | 6 | 7 | $38.36 | $41.83 |

| Texas | 27 | 30 | 5 | 5 | $36.34 | $39.68 |

| Utah | 26 | 28 | 8 | 8 | $39.91 | $44.54 |

| Vermont | 26 | 25 | 7 | 7 | $38.58 | $42.25 |

| Virginia | 27 | 29 | 6 | 7 | $40.00 | $40.36 |

| Washington | 26 | 28 | 7 | 8 | $37.36 | $40.52 |

| West Virginia | 30 | 31 | 9 | 10 | $40.04 | $42.91 |

| Wisconsin | 28 | 30 | 8 | 9 | $40.31 | $45.53 |

| Wyoming | 28 | 29 | 6 | 8 | $38.95 | $43.21 |

| Puerto Rico | 6 | 6 | — | — | $42.40 | $52.03 |

| American Samoa | 1 | 1 | — | — | $34.70 | $43.40 |

| Guam | 2 | 2 | — | — | $39.88 | $45.38 |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 1 | 1 | — | — | $37.20 | $30.20 |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | 1 | 1 | — | — | $42.60 | $47.40 |

| NOTES: PDP is prescription drug plan. U.S. total count excludes PDPs in the territories. Totals include sanctioned plans closed to new enrollees as of September of prior year. Average monthly premium is weighted by September 2019 enrollment. Benchmark plan counts include “de minimis” plans, which can retain Low-Income Subsidy beneficiaries despite exceeding the benchmark premium by a minimal amount (up to $2 in 2020). Benchmark plans are not shown for the territories because the LIS is not available to residents of the territories. SOURCE: KFF analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2019-2020 Part D plan files. | ||||||

Table 2: National Medicare Part D Stand-alone Prescription Drug Plans in 2020 | ||||||||

PDP name | Type of plan | Benchmark PDP | Enrollment1 | Weighted average monthly premium2 | ||||

Number (in millions) | % of total | Top 10 in 2019 | 2019 | 2020 | % change | |||

ALL PDPs | 20.49 | 100.00% | $39 | $42 | 7% | |||

AARP MedicareRx Preferred | Enhanced3 | No | 2.21 | 10.8 | 2 | $75 | $79 | 6% |

AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus | Basic | Yes | 1.25 | 6.1 | 5 | $34 | $32 | -4% |

AARP MedicareRx Walgreens | Enhanced | No | 0.74 | 3.6 | 8 | $28 | $34 | 23% |

Cigna-HealthSpring Rx Secure | Basic | Yes4 | 0.51 | 2.5 | $32 | $30 | -5% | |

Cigna-HealthSpring Rx Secure-Essential | Enhanced | No | 0.07 | 0.3 | $22 | $22 | 1% | |

Cigna-HealthSpring Rx Secure-Extra | Enhanced | No | 0.15 | 0.7 | $57 | $57 | <1% | |

EnvisionRxPlus | Basic4 | Yes4 | 0.54 | 2.6 | $17 | $16 | -3% | |

Express Scripts Medicare – Choice | Enhanced | No | 0.05 | 0.2 | $93 | $83 | -11% | |

Express Scripts Medicare – Saver | Enhanced | No | 0.21 | 1.0 | $24 | $25 | 1% | |

Express Scripts Medicare – Value | Basic | Yes5 | 0.45 | 2.2 | $35 | $36 | 2% | |

Humana Basic Rx Plan | Basic | Yes4 | 1.57 | 7.7 | $31 | |||

Humana Preferred Rx Plan | Crosswalked to Humana Basic Rx Plan | 4 | $31 | -1% | ||||

Humana Premier Rx Plan | Enhanced | No | 2.62 | 12.8 | $57 | |||

Humana Walmart Rx Plan | Crosswalked to Humana Premier Rx Plan | 3 | $28 | 107% | ||||

Humana Enhanced | Crosswalked to Humana Premier Rx Plan | 9 | $76 | -25% | ||||

Humana Walmart Value Rx Plan | Enhanced | No | New in 2020 | $136 | ||||

SilverScript Choice | Basic | Yes4 | 4.40 | 21.5 | 1 | $31 | $29 | -7% |

WellCare Classic | Basic | Yes4 | 0.89 | 4.3 | 7 | $32 | $29 | -9% |

WellCare Medicare Rx Saver | Basic | Yes4 | 1.17 | 5.7 | $31 | |||

Aetna Medicare Rx Saver | Crosswalked to WellCare Medicare Rx Saver | 6 | $29 | 6% | ||||

WellCare Medicare Rx Select | Enhanced | No | 0.70 | 3.4 | $21 | |||

Aetna Medicare Rx Select | Crosswalked to WellCare Medicare Rx Select | 10 | $17 | 23% | ||||

WellCare Medicare Rx Value Plus | Enhanced | No | 0.52 | 2.5% | $72 | |||

Aetna Medicare Rx Value Plus | Crosswalked to WellCare Medicare Rx Value Plus | $60 | 20% | |||||

WellCare Extra | Crosswalked to WellCare Medicare Rx Value Plus | $71 | 1% | |||||

WellCare Value Script | Enhanced | No | 0.74 | 3.6% | $15 | $17 | 14% | |

WellCare Wellness Rx | Enhanced | No | New in 2020 | $146 | ||||

| NOTES: PDP is prescription drug plan. Analysis excludes enrollees in employer group plans. 1Enrollment as of September 2019, includes enrollees with and without low-income subsidies; for enrollees being crosswalked into new plan for 2020, enrollment is shown in the crosswalked plan. Top 10 in 2019 based on March 2019 enrollment. 2Weighted by September 2019 enrollment. 3In all regions except territories. 4In most regions. 5In some regions. 6Unweighted median because PDP is new for 2020.SOURCE: KFF analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2019-2020 Part D plan files. | ||||||||

| Table 3: Benefit Designs and Deductibles in Medicare Part D Stand-alone Prescription Drugs Plans, 2019 and 2020 | ||

| 2019 | 2020 | |

| Share of PDPs offering (number of plans1) | ||

| Basic benefits | 39% (348) | 40% (382) |

| Enhanced benefits | 61% (553) | 60% (566) |

| Standard deductible | 52% (468) | 69% (654) |

| Lower deductible | 19% (170) | 17% (161) |

| No deductible | 29% (263) | 14% (133) |

| Weighted average monthly PDP premium2 | ||

| Basic benefits | $31.97 | $30.90 |

| Enhanced benefits | $48.76 | $57.03 |

| Standard deductible | $31.54 | $36.03 |

| Lower deductible | $33.93 | $31.78 |

| No deductible | $75.37 | $80.60 |

| NOTES: PDP is prescription drug plan. 1Excludes plans in the territories. 2Weighted by September 2019 enrollment.SOURCE: KFF analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2019-2020 Part D plan files. | ||

| Table 4: Median Cost Sharing for National Medicare Part D Stand-alone Prescription Drug Plans, 2019 and 2020 | ||||||||||

| Plan name | Formulary tier cost-sharing amounts | |||||||||

| Preferred generics ($) | Generics ($) | Preferred brands1 | Non-preferred drugs (%) | Specialty tier drugs (%) | ||||||

| 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| ALL PDPs | $1 | $0 | $5 | $3 | $40/ 20% | $42/ 25% | 40% | 38% | 25% | 25% |

| AARP MedicareRx Preferred | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | $40 | $45 | 40% | 40% | 33 | 33 |

| AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | $25 | $26 | 33 | 35 | 25 | 25 |

| AARP MedicareRx Walgreens | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | $30 | $40 | 32 | 32 | 25 | 25 |

| Cigna-HealthSpring Rx Secure-Essential | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 20% | 18% | 49 | 43 | 25 | 25 |

| Cigna-HealthSpring Rx Secure-Extra | 4 | 4 | 10 | 10 | $42 | $42 | 50 | 50 | 31 | 31 |

| Cigna-HealthSpring Rx Secure | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | $30 | $30 | 36 | 36 | 25 | 25 |

| EnvisionRxPlus | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | $34 | $352 | 36 | 33 | 25 | 25 |

| Express Scripts Medicare Choice | 2 | 2 | 7 | 7 | $42 | $42 | 48 | 48 | 26 | 28 |

| Express Scripts Medicare Saver | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 18% | $30 | 32 | 47 | 25 | 25 |

| Express Scripts Medicare Value | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | $25 | $25 | 39 | 35 | 25 | 25 |

| Humana Basic Rx Plan | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 25% | 25% | 37 | 38 | 25 | 25 |

| Humana Premier Rx Plan | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | $47 | $42 | 35 | 44 | 25 | 25 |

| Humana Walmart Value Rx Plan | n/a | 1 | n/a | 4 | n/a | $47 | n/a | 35 | n/a | 25 |

| SilverScript Choice | 3 | 0 | 13 | 1 | $42 | $47 | 45 | 38 | 33 | 27 |

| WellCare Classic | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | $37 | $32 | 41 | 34 | 25 | 25 |

| WellCare Medicare Rx Saver | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | $30 | $28 | 35 | 38 | 27 | 25 |

| WellCare Medicare Rx Select | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | $47 | $47 | 40 | 42 | 25 | 25 |