Policymakers have had ongoing concerns about the financial health of rural hospitals and the implications for access to care and the local economy. Rural hospital finances improved during the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of government relief funds. However, industry reports suggest that the outlook for the hospital sector as a whole deteriorated in 2022 as these funds have gone away and due to ongoing effects of the pandemic (such as labor shortages), rising prices, and investment losses. Concerns about the viability of rural hospitals have been cited as one factor that could potentially motivate lawmakers to expand Medicaid in the eleven states that have not already done so. These non-expansion states collectively account for about one-third (34%) of rural hospitals, based on our analysis of 2021 hospital cost report data.

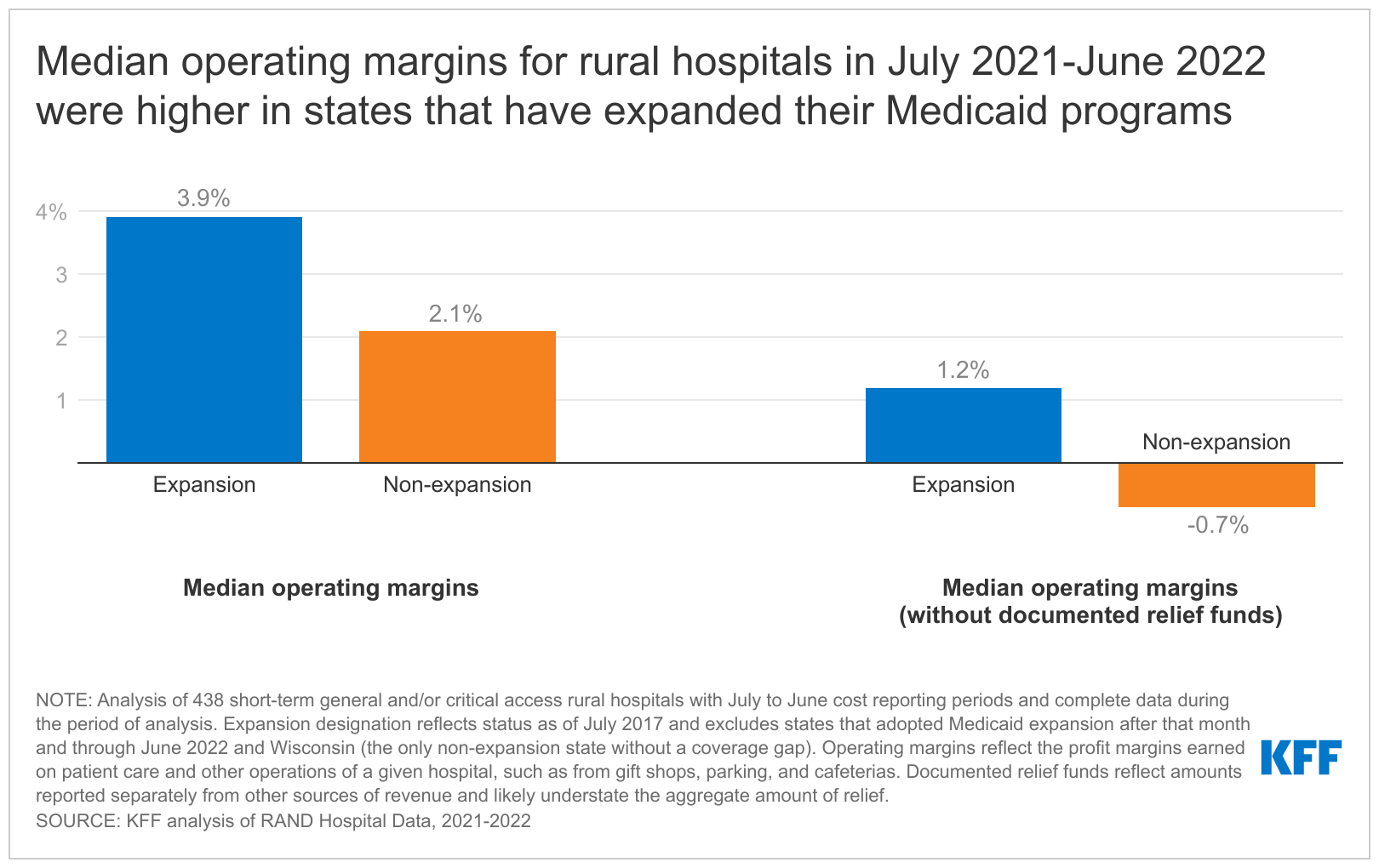

In this data note, we provide a background on rural hospital finances and use hospital cost report data to describe operating margins among rural hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Methods for details). We find that median operating margins among the rural hospitals in our analysis increased earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic, likely as a result of government relief funds, but that these facilities face renewed financial challenges, especially in states that have not expanded Medicaid (Figure 1). Among rural hospitals in non-expansion states, median operating margins were 2.1 percent during the July 2021-June 2022 period and were -0.7 percent when excluding documented relief funds. In Medicaid expansion states, median operating margins dropped, but remained positive even after excluding documented relief funds.

Rural hospital finances leading into the pandemic

Rural hospitals have faced unique financial challenges that precede the COVID-19 pandemic. Among other challenges, rural hospitals tend to have low patient volumes—given that they serve small populations and residents increasingly travel to urban facilities to receive their care—which may lead to higher costs on average and may limit the ability of rural facilities to offer specialized services. From 2010 to 2019, 114 rural hospitals eliminated inpatient services or closed altogether, while others eliminated specific service lines, such as obstetric units. According to our analysis, in 2019, the year before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, median operating margins were 1.5% among rural hospitals, compared to more than three-times that rate (5.2%) among other hospitals (data not shown).

Although rural hospitals face a common set of challenges, operating margins varied substantially across facilities. For example, we found that about two-fifths (41%) of rural hospitals had negative operating margins in 2019, though about one-third (32%) had operating margins at or above 5.0% in the same year (data not shown). One previous study found that median margins on patient care are greater among large versus small rural hospitals, though another analysis found that closures were less likely among Critical Access Hospitals (rural facilities that are eligible for cost-based reimbursement from Medicare on the basis of having 25 or fewer acute inpatient beds and either meeting distance requirements from the nearest hospital or being deemed a necessary provider by the state prior to 2006). The latter study also found that closures were more likely among for-profit hospitals, Medicare Dependent Hospitals (rural facilities that are eligible for greater Medicare reimbursement on the basis of having high Medicare inpatient shares and 100 or fewer beds), hospitals in the South, and hospitals in states that have not expanded Medicaid.

Median operating margins among rural hospitals were higher in expansion than non-expansion states in 2019 (2.0% versus 0.3%) based on our analysis (data not shown), which is consistent with research suggesting that expanding Medicaid has improved the financial performance of hospitals. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded Medicaid coverage for most low-income adults to 138% of the federal poverty level, though a June 2012 Supreme Court decision effectively allowed states to decide whether to adopt the Medicaid expansion. Currently, eleven states have not expanded Medicaid, and they are largely in the South. Previous research has found that Medicaid expansion has resulted in decreases in uncompensated care, increases in operating margins, and decreases in closures of hospitals and obstetric units. Medicaid expansion improves hospital finances by extending coverage to uninsured patients who would otherwise qualify for hospital charity care or be unable to pay their bills. Among studies that have evaluated the effect of Medicaid expansion on urban and rural hospitals separately, most reported that improvements in financial performance have been concentrated among rural hospitals. Although research suggests that expanding Medicaid has improved the financial performance of rural hospitals, it may not be a panacea. For instance, while median operating margins among rural hospitals were higher in expansion than non-expansion states in 2019 (2.0% versus 0.3%), they were still lower than median operating margins among non-rural hospitals in expansion states (4.2%) (data not shown).

Trends during the pandemic

The financial performance of rural hospitals improved substantially early in the pandemic, likely as a result of government relief funds. Median operating margin among rural hospitals increased from 1.0% during July 2017-June 2019 to 7.7% during July 2019-June 2021 based on our analysis of a subset of hospitals (see Methods for details). Rural hospital closures had been increasing since 2017 before peaking at 19 closures in 2020 (the largest number since at least 2005) and then dropping to 2 closures in 2021 (the smallest number since at least 2005).

The large improvement in the financial performance of rural hospitals likely reflects the receipt of government relief funds, including dollars that were targeted specifically towards rural hospitals. Subtracting out relief funds documented in hospital cost reports lowers median operating margins during July 2019-June 2021 from 7.7% to 3.9%, according to our analysis. It appears that some hospitals did not separately or completely report relief funds, meaning that our estimates may overstate what operating margins would have been in the absence of relief funds, and potentially substantially so. In other words, relief funds likely played an even more substantial role in supporting rural hospital operating margins than suggested by our analysis.

Rural hospitals now face renewed financial challenges. After increasing substantially earlier in pandemic, median operating margins among the rural hospitals in our analysis fell from 7.7% in July 2019-June 2022 to 3.3% in the July 2021-June 2022 period. When subtracting out relief funds documented in hospital cost reports, median operating margins were slightly lower than pre-pandemic levels during the July 2021-June 2022 period and would likely have been even lower if accounting for relief funds that were not specifically documented by hospitals. Industry reports suggest that the outlook for hospitals and health systems deteriorated in 2022, which is only partially reflected in our analysis of July 2021-June 2022 data. In this context, it is not clear whether hospital closures may reemerge as an issue facing rural communities. There were seven hospital closures in 2022, which was greater than the number in 2021 (2 closures), but still less than the average number from 2005-2022 (10.3).

Median operating margins among rural hospitals were lower in non-expansion states than in expansion states in each period of our analysis, leaving these facilities in weaker financial standing to confront the challenges that have faced the hospital sector in recent months. For example, during the July 2021-June 2022 period, median operating margins among rural hospitals in our analysis fell to 2.1% in non-expansion states (compared to 3.9% in expansion states) and -0.7% when subtracting out documented relief funds (compared to 1.2% in expansion states).

Looking ahead

There may be additional challenges for rural hospitals on the horizon. First, key sources of COVID-19 relief have been largely depleted. This includes Phase 4 Provider Relief Funds—which were intended to be greater for smaller providers—and American Rescue Plan (ARP) rural funds, both of which may have helped sustain rural hospitals during July 2021-June 2022. Second on March 31, 2023, a provision will end that has required states to keep people in Medicaid continually enrolled during the pandemic in exchange for enhanced federal matching funds. A KFF analysis estimated that between 5 and 14 million people could lose Medicaid enrollment as a result, which may increase uncompensated care costs for rural and other hospitals. Finally, the Biden administration has announced plans to end COVID-19 emergency declarations on May 11, 2023. This would eliminate numerous health care policies and regulations that could have implications for hospital finances, such as a 20 percent increase in the Medicare payment rate for hospitalized patients who are diagnosed with COVID-19.

Policymakers have implemented a number of initiatives that are intended to support rural hospitals or restructure the rural health care delivery system. For example, in December 2022, Congress passed an omnibus spending bill that included a two-year extension of Medicare payment adjustments targeted towards rural hospitals. The federal government also recently implemented a new payment model, the Rural Emergency Hospital designation, which provides additional resources intended to sustain emergency and outpatient services at facilities that may no longer be able to support inpatient care. Finally, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is testing the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model which provides rural hospitals with an all-payer global budget and is intended to reduce costs, increase quality, and improve the sustainability of rural hospital finances.

It is unclear whether current policy initiatives will be sufficient to sustain access to care in rural areas, especially in states that have not expanded Medicaid, where hospitals are facing greater financial challenges.

Methods

Our analysis is based on RAND Hospital Data, which is a cleaned and processed version of annual cost report data submitted by hospitals to the Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS). Every Medicare-certified hospital must submit a cost report, meaning that HCRIS data encompass all US hospitals except federal hospitals and some children’s hospitals. We conducted additional data cleaning, assigned cost report data to years based on the reporting period end date (which varies across facilities), and focused on short-term general and/or critical access hospitals. We identified rural areas based on a definition from the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, which the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) uses to determine eligibility for Rural Health Grants.

Operating margins reflect the profit margins earned on patient care and other operations of a given hospital, such as from gift shops, parking, and cafeterias. They are calculated by dividing the difference between operating revenues and expenses (also known as “net operating income”) by operating revenues. We excluded investment income and charitable contributions from operating revenues but included government appropriations, which may be critical for sustaining the operations of some hospitals.

We defined expansion and non-expansion states differently based on the period of analysis. When analyzing 2019 data, we defined expansion states to include all states that had expanded Medicaid through that year (including Virginia, which did so on January 1, and Maine, which did so on January 10, with coverage retroactive to July 2, 2018). We defined all remaining states as non-expansion states, except for Wisconsin, which covers individuals up to 100 percent of the federal poverty level and therefore does not have a coverage gap. We began with the same set of states when analyzing July 2017-June 2022 data but excluded seven states that expanded during that period (Idaho, Maine, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Utah, and Virginia). All analyses included South Dakota as a non-expansion state, given that it expanded Medicaid after our period of analysis.

Our analysis of 2019 data included 2,117 rural hospitals and 2,179 urban hospitals and our analysis of trends included 527 rural hospitals, i.e., 25% of all rural hospitals with 2019 data. When evaluating operating margins by expansion status, we excluded hospitals from some states (as described above), leaving 2019 data for 1,201 and 845 hospitals from expansion and non-expansion states, respectively, and trend data for 305 and 133 hospitals, respectively. For our trend analysis, we focused on rural hospitals with July to June reporting periods, given that this was the second-most common reporting period and, as of February 2023, RAND Hospital Data from 2022 were rarely available for the most common reporting period (January to December). We also focused on hospitals with complete data from June 2017-June 2022. We found similar patterns (but different operating margins) when evaluating the much larger group of hospitals with complete 2018-2021 data (1,938 facilities or about 92% of all rural hospitals with 2019 data). Among those hospitals, operating margins increased from 1.2% in 2018-2019 to 7.7% in 2020-2021 (or 2.4% when excluding documented relief funds). Among the hospitals in our trend analysis, operating margins increased from 1.0% in 2018-2019 to 7.7% in 2020-2021 (or 3.9% when excluding documented relief funds). Median operating margins were also higher among hospitals in expansion versus non-expansion states during the 2018-2019 and 2020-2021 periods when evaluating the larger group of hospitals with complete 2018-2021 data. The magnitude of this difference during the 2020-2021 period was smaller overall (8.3% among expansion states versus 6.5% among non-expansion states compared to 8.5% versus 5.6% in our trend analysis) but larger after removing documented relief funds (3.5% versus 0.0% compared to 4.9% versus 2.6% in our trend analysis).

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.