Key Takeaways

- The federal Title X family planning program has undergone substantial changes in the number of participating clinics in response to shifting program priorities and rules that vacillate widely between different administrations, particularly about how counseling and referral to abortion services are handled by grant recipients.

- The Trump Administration regulations that prohibited grantees from referring clients for abortion services or having co-located family planning and abortion services led to a withdrawal of almost a third of the sites from the Title X network. The reduction of the provider network and limits to in person care during the COVID-19 pandemic translated to a major reduction in the number of people served by the program from 3.9 million people in 2018 to 1.5 million in 2020, a 60% drop.

- The Biden Administration issued regulations to reverse the Trump Administration policies banning abortion referrals and the participation of family planning providers that also offer abortion services in the program. Today, the Title X network has even more sites than the number participating prior to initiation of the Trump Administration regulations.

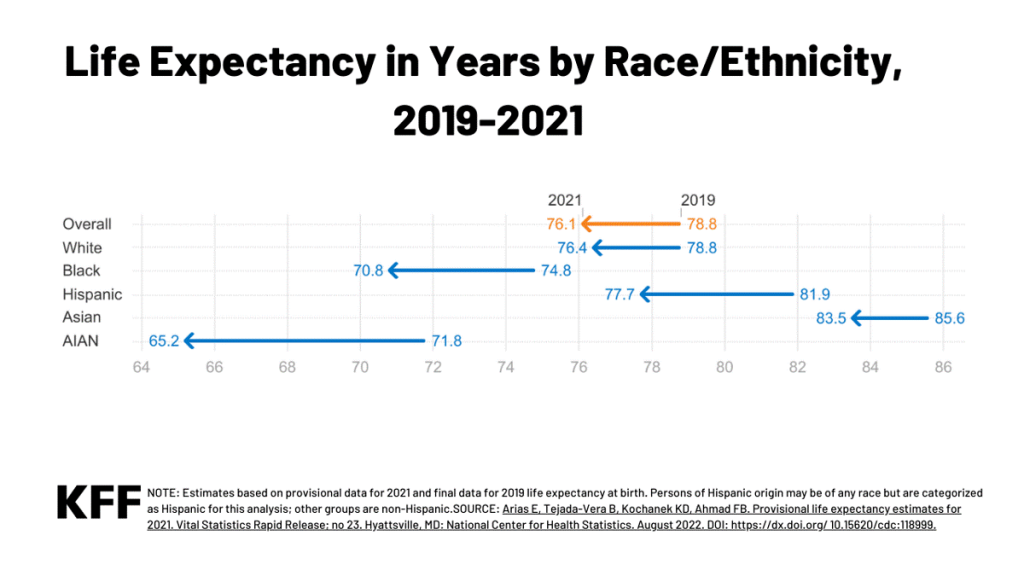

- The Title X family planning program has been level funded at $286 million for nearly a decade, and as a result, has not been able to keep up with medical price inflation or the growing demand for family planning services.

- While the size of the family planning network has largely recovered, ongoing litigation challenging the Biden Administration regulations and the program’s provision allowing minors to get contraception without parental consent could result in limits to the availability of federally supported family planning services in some states.

- In states with abortion bans, continued participation in the Title X program may be impeded by state laws that prohibit pregnancy options counseling that includes abortion and referrals, a current requirement of the Title X program. The state of Tennessee (a Title X grantee) has already been disqualified because of their refusal to provide comprehensive pregnancy options counseling and abortion referral for those who seek it. In six of the states where abortion is banned (AL, AR, LA, OK, WI, and WV), the health department is the only Title X grantee.

Introduction

The federal Title X program, which has been in existence since 1970, has historically provided family planning services to nearly four million individuals a year through a network of approximately 4,000 clinic sites. The program is part of the U.S. public health safety net that is designed to serve individuals with lower incomes and those without insurance who otherwise may not be able to afford family planning services. Over the past number of years, the program has undergone substantial changes in the number of participating clinics and individuals it has been able to serve due to regulation changes and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Title X program is led by a Deputy Assistant Secretary for Population Affairs who is appointed by the president, with program priorities and rules vacillating widely between different administrations. In particular, a provision of the Title X statute, Section 1008, that specifies that no federal funds appropriated under the program “shall be used in programs where abortion is a method of family planning” has been interpreted differently depending on who is in leadership. Throughout most of the history of the program, the ban has generally been understood to mean that Title X funds cannot be used to pay for or support abortion. However, the Trump and Reagan Administrations interpreted this more expansively as meaning that in addition to not paying for abortions, grantees were not permitted to use federal funds to promote, counsel, or refer clients for abortion or have co-located family planning services and abortion activities.

This interpretation, referred to as the Domestic Gag Rule by its opponents, is similar to the Mexico City Policy that requires foreign nongovernmental organizations to certify that they will not “perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning” using funds from any source (including non-U.S. funds) as a condition of receiving U.S. global family planning assistance. This policy has been reinstated and rescinded with the changing administrations for many years, which could be the future of the Title X regulations.

Title X Regulation Changes

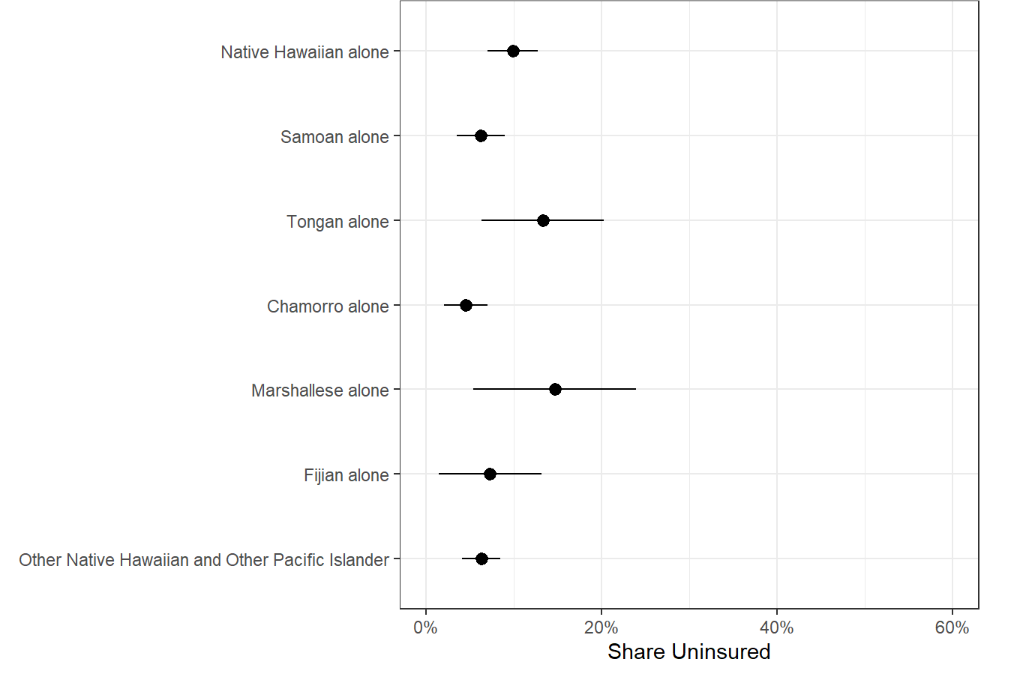

In 2019, the Trump Administration made significant changes to the Title X regulations, which prohibited participating family planning clinics from providing abortion referrals and having co-located abortion services. This allowed grantees that had not previously participated in the program due to the requirement to provide nondirective pregnancy options counseling to begin receiving funding, such as the Obria Group, Inc., a Christian organization based in Southern California. Two other grantees joined the program under the Trump Administration, City of El Paso in Texas and Osceola Community Health Services in Florida. The new program regulations most notably resulted in a mass exodus of clinics from the Title X network, including over 400 Planned Parenthood clinics and almost 900 other Title X sites. From June 2019 to August 2021, almost a third of the Title X sites left the program (Figure 1).

Not long after the clinics started leaving the program, the COVID-19 pandemic began, where fewer people were seeking in-person care. In 2018, the Title X program served 3.9 million clients, which decreased to 1.5 million by 2020, over a 60% reduction, due to the decrease in size of the network and the COVID-19 pandemic. After President Biden was elected in November 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued proposed regulations in April 2021 reversing the Trump Administration’s regulations and again requiring comprehensive pregnancy options counseling and abortion referrals when desired, as well as allowing co-located abortion services. These regulations were finalized and became effective in November 2021 (Figure 2).

In January 2022 as part of the American Rescue Plan HHS awarded $6.6 million to 8 grantees to address “dire family planning needs” as part of a series of actions HHS took in response to Texas Law SB 8, which banned abortions in Texas after 6 weeks of pregnancy (Table 1).

Title X Service Grants

In March 2022, HHS released a new funding announcement under the new regulations, which resulted in funding for 16 of the 18 grantees that had left the program under the Trump regulations. The two grantees that did not return as FY2022 grantees were Planned Parenthood of Illinois and Health Imperatives, Inc. in Massachusetts, although the network of clinics for these grantees stayed in the program, returning as sites under the Illinois Dept. of Public Health Family Planning Program and Massachusetts Department of Public Health grants, respectively. (Individual grantees can encompass multiple sites and clinics.) FY2022 grants were awarded to 76 grantees for a total of $256.6 million. The program has been level funded at $286 million for the past nine years despite inflation (Figure 3).

While these 76 grantees received 5-year awards to support their family planning networks, 13 grantees only received a one-year grant for FY2022 due to funding constraints. This resulted in 89 grantees funded at $265 million in FY2022 (Table 2). Additionally, in May 2022, HHS awarded supplemental funds totaling $16.3 million to 31 grantees to enhance and expand their telehealth infrastructure and capacity after the increase in the use of telehealth due to the pandemic. These funds were also made available through the American Rescue Plan for a 12-month project period.

For FY2023, HHS funded 87 grantees with $256 million. Eleven of the grantees that only received a one-year grant for FY2022 were re-funded in FY2023 with six receiving level funding and five receiving a decrease in funding. The City of El Paso did not reapply for FY2023 funding, and the State of Tennessee lost their Title X grant due to non-compliance with Title X regulations by not providing comprehensive pregnancy options counseling that includes referrals for abortion when desired.

Rebuilding the Title X Network

The Title X network has been rebuilding under the new regulations and funding. Of the 411 Planned Parenthood sites that left the program, 286 sites (70%) have rejoined.

Of the 869 other sites that left the program, 531 (61%) have returned. At the same time, there are 777 new sites that were previously not part of the program. This brings the current Title X network back to 4,108 sites, which is 2% more than the original 4,010 sites prior to the Trump regulations.

All six states that left the Title X network (HI, ME, OR, UT, VT, WA) under the Trump Administration’s regulations have returned with most of their sites or they have expanded their networks to new sites.

While most states had small increases in funding amounts from FY2019 to FY2022, California had a 42% decrease in funding from $21 million to $13.2 million. The state still managed to expand the number of Title X sites in their network and the grantee, Essential Access Health, recently received $60 million in state funding to expand reproductive health care for low-income individuals.

Nevada, which has five grantees, lost over a quarter of its funding from FY2019 to FY2022. Two of the grantees received larger grants (Nevada Primary Care Association and Southern Nevada Health District) and three of the grantees received less (Washoe County Health District, State of Nevada Division of Public & Behavioral Health, City of Carson City DBA Carson City Health & Human Services). Iowa has had a slight decrease in funding and the number of Title X clinics in Iowa has decreased by over 40%, largely due to the loss of the Planned Parenthood clinics in their network.

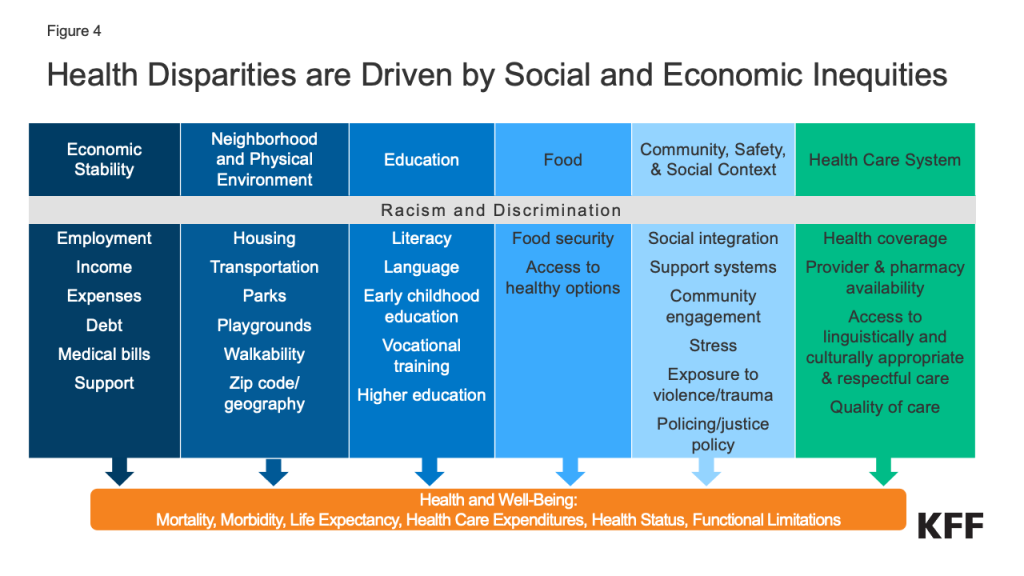

Impact of State Restrictions on Title X Funding

Two new grantees to the program, Bridgercare in Montana and Converge, Inc. in Mississippi, took over the Title X grants in their respective states in March 2022 after the state health departments had been the grantees for decades. Both grantees received slight increases in funding and Converge, Inc has been able to maintain Mississippi’s previous Title X network. However, the size of Montana’s Title X network has decreased slightly in response to a law passed by the Montana Legislature (House Bill 620), which prohibited the state from funding any organization that provides abortions, effectively excluding Planned Parenthood clinics from their Title X program.

In March 2023, Tennessee lost their Title X funding because of a state policy that required Title X clinics to only provide pregnancy options counseling for the options legal in the state, which excluded abortion, which is in violation of the federal requirements to provide comprehensive pregnancy options counseling. While Tennessee’s governor has said that the state will fund the health department for their lost Title X funding with $7.5 million in recurring annual state funding, it is unclear how long the state will maintain this funding. In Idaho, the Attorney General has clarified that the Idaho law banning abortion also prohibits Idaho medical providers from referring a woman across states lines to access abortion services, which would also be in violation of the Title X regulations requiring pregnancy options counseling. Planned Parenthood Great Northwest, Hawai’i, Alaska, Indiana, Kentucky, which is one of two Title X grantees in Idaho, is suing the Attorney General of the State of Idaho over their inability to provide comprehensive pregnancy options counseling to their clients.

This could become an issue in other states where abortion is banned and state laws or policies may be in direct conflict of Title X federal requirements, disqualifying a state health department from being a Title X grantee. There are currently 34 states with grantees that are state health departments and in 16 states the health department is the only Title X grantee, six of these are states where abortion is banned (AL, AR, LA, ND, SD, WI).

Current Title X Litigation

There are currently two lawsuits filed against HHS challenging aspects of the current Title X regulations. In a case filed in United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, Amarillo Division in April 2020, Deanda v. Becerra, a father of three minor girls contends that the Title X provisions allowing minors to seek contraception without parental consent violates his rights as a parent under Texas law, and the due process clause of the fourteenth amendment. Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, the only judge in the Amarillo division (and the same federal judge overseeing a case challenging approval of the abortion medication Mifepristone) ruled in favor of the plaintiff, stating that Title X does not preempt state laws requiring parental consent or notification before distributing contraception to minors, and that the Biden Administration Title X requirement violates the plaintiff’s fundamental right to control and direct the upbringing of his minor children. On December 20, 2022, the Court struck down as unlawful the provision of the regulations requiring Title X projects to provide minors services without requiring consent or notification of their parents or guardians. This ruling is not limited to the plaintiff or to Texas. In states that require parental consent or notification, minors may no longer be able to obtain contraceptive services without consent or notification. In February 2023, the Biden Administration appealed this decision to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. The case is pending at the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Biden Administration has requested oral argument.

On October 25, 2021, the state of Ohio, joined by 11 other states (AL, AZ, AK, FL, KS, KY, MO, NE, OK, SC, WV), filed a lawsuit in the US District Court for the Southern District of Ohio against HHS to block the implementation of the Biden Administration’s regulations. These states claim the final regulations violate Section 1008 of the Public Health Service Act that says none of the funds appropriated under Title X can be used in programs where abortion is a method of family planning. The litigants claim that by reinstating the regulations that allow co-located abortion services and require participating providers to offer referrals for abortions to clients who seek them, that HHS is not in compliance with the intent of the law. On December 29, 2021, the district court denied the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction to block the Department of Health and Human Services from implementing or enforcing the final rule. The plaintiff states appealed this ruling to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals and the court heard oral arguments on October 27, 2022. In April 2023, the state of Arizona dropped out of the case (as the new governor and attorney general shifted to a Democratic administration). While this case is pending, the Biden Administration regulations, except for the parental consent provisions affected by the Deanda case discussed below, are in effect.

Looking Forward

The Biden Administration’s reversal of the Trump Administration’s Title X regulations has enabled grantees that left the program under the Trump regulations to rejoin. Many states have been able to rebuild their networks to where they were in 2019, and in some cases, have been able to increase the number of clinics in their networks. However, funding for Title X has not increased for the past nine years and some states are operating larger Title X networks with significantly less federal funding (e.g., California and Nevada).

With abortion banned or restricted in many states, access to Title X sexual and reproductive health services becomes even more important. While Tennessee is the first state to lose their Title X funding due to non-compliance around pregnancy options counseling after abortion has been banned in their state, other states may have similar conflicts. States with abortion bans may refuse to comply with the Title X regulations that require offering pregnancy options counseling that includes prenatal care and delivery; infant care, foster care, or adoption; and pregnancy termination, as well as abortion referrals upon request. In states where abortion is banned or restricted, this would require out-of-state referrals for those desiring abortion services.

HHS has released a grant opportunity forecast for $1.5 million designed to fund a currently funded Title X grantee to establish the Title X Nondirective Options Information, Counseling, and Referrals Hotline that will provide pregnant people with neutral and factual information, as well as nondirective counseling and referrals for those seeking this information. This hotline could help give people access to comprehensive information about pregnancy options regardless of where they live.

While there may be gaps in some states, HHS anticipated that the number of clients served by the program would return to around 4 million nationally by 2023, and with the Title X networks back to capacity in many states, it seems on track to reach that projection.