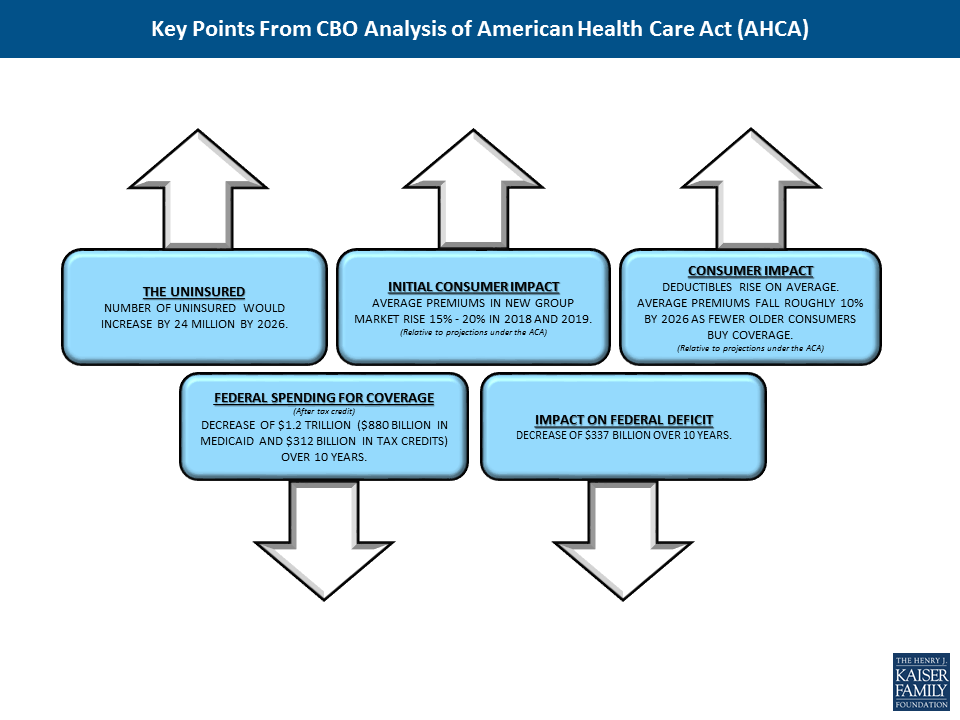

Key Points from Congressional Budget Office Analysis of American Health Care Act

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

A new brief from the Kaiser Family Foundation explains the role that Medicaid plays for nearly 7 million nonelderly adults with disabilities in the U.S. and explores what the American Health Care Act could mean for their health care and coverage.

Medicaid covers more than three in 10 nonelderly adults with disabilities, including people with physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, and traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries; intellectual or developmental disabilities such as Down syndrome and autism; and mental illness. Over half who are enrolled in Medicaid live below the federal poverty level. They are four times as likely to receive nursing or other health care at home, and more than 1.5 times as likely to have 10 or more health care visits in a year compared to those with private insurance.

Through Medicaid, nonelderly adults with disabilities have access to regular preventive care as well as medical care for illnesses and chronic conditions. States must provide certain minimum services for adults, such as inpatient and outpatient hospital, physician, lab and x-ray, and nursing home services. States also can choose to provide a broad range of optional services such as prescription drugs, physical therapy, private duty nursing, personal care, rehabilitative services, and case management.

The changes to Medicaid in the House GOP bill – notably the end of enhanced funding for the ACA Medicaid expansion and the fundamental change in program financing to a per capita cap – carry significant implications for this population. For those who have gained Medicaid eligibility through the expansion, loss of the enhanced match could curtail their prospects for keeping that coverage. And while per capita cap financing could come with increased flexibility for states in subsequent legislation, the associated federal funding reductions over time may lead states to consider cuts in Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and provider reimbursement. Nonelderly adults with disabilities could be particularly affected by such cuts, as many rely on Medicaid coverage pathways and services that are offered at state option and have higher spending, due to their greater need for acute and long-term care services.

The White House released its budget blueprint on March 16, 2017 providing initial information on its budget request for FY18 (the full budget request is expected in May). While detail on funding levels for most global health programs is not specified, the blueprint does include total funding for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Department of State and highlights some specific global health programs and related areas:

Key Takeaways

This brief describes Medicaid’s role for nearly 7 million nonelderly adults with disabilities living in the community to help inform the debate about the American Health Care Act’s proposals to end enhanced federal funding under the ACA and reduce federal Medicaid funding under a per capita cap.

Medicaid covers more than three in 10 nonelderly adults with disabilities, providing a broad range of medical and long-term care services that enable people with disabilities to live and work in the community.

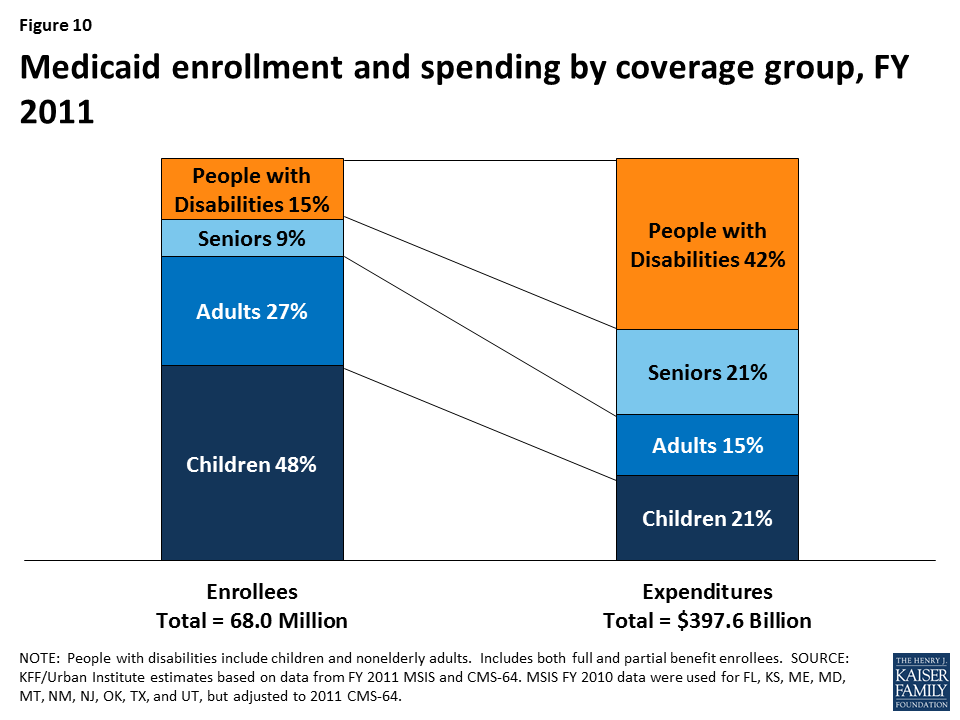

People with disabilities account for 15% of total Medicaid enrollment but 42% of program spending due to their greater health needs and more intensive service use.

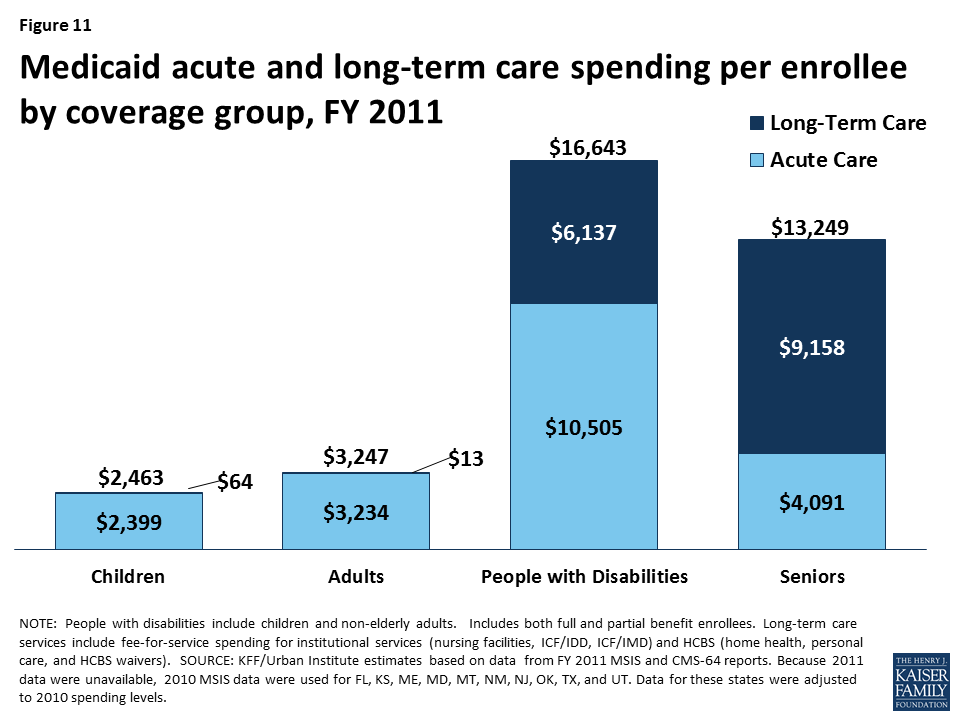

Medicaid spending per enrollee for people with disabilities is substantially higher than for those without disabilities, due to their greater health needs and reliance on Medicaid for expensive but necessary services, especially long-term care in the community and nursing homes, that are generally unavailable through private insurance and too costly to afford out-of-pocket. Medicaid spending per enrollee for people with disabilities also varies substantially by state (from $10,142 in AL to $33,808 in NY in 2011).

Nonelderly adults with disabilities may be particularly affected by Medicaid changes in the American Health Care Act (AHCA), including the fundamental shift to per capita capped financing.

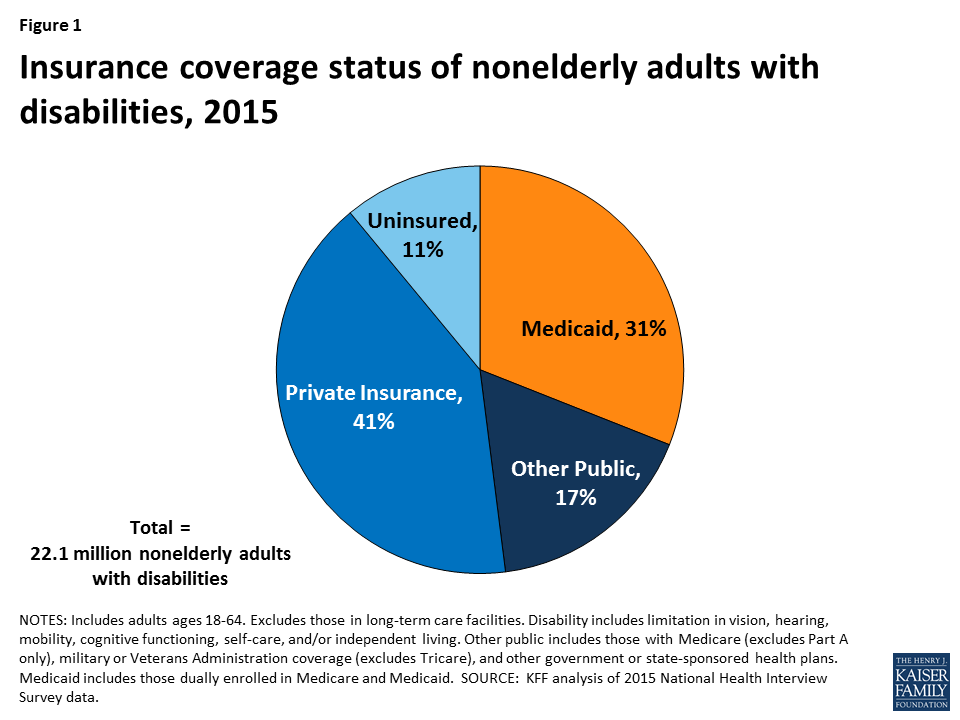

Over 22 million nonelderly adults, or 12% of adults ages 18 to 64, living in the community in the United States have a disability as of 2015.1 They include people with physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, and traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries; intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD), such as Down syndrome and autism; and mental illness. Some people live with a disability from birth or childhood, while others have a disability onset later in life resulting from an injury or chronic illness. Medicaid plays an important role by providing health insurance coverage for more than one in three nonelderly adults with disabilities (Figure 1).

The House American Health Care Act bill calls for changes to Medicaid that could affect nonelderly adults with disabilities. Some nonelderly adults with disabilities have gained Medicaid eligibility through the ACA’s expansion, and the House bill calls for eliminating the expansion’s enhanced federal matching funds.2 The House bill also contains changes to Medicaid’s financing structure in ways that would limit federal funding through a per capita cap. While states could be offered increased flexibility beyond what is available under current law in future legislation, states may look to cuts in Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and provider reimbursement as a result of the associated federal funding reductions. People with disabilities have higher Medicaid spending relative to other populations due to their greater health needs and more intensive service use. Nonelderly adults with disabilities could be particularly affected by potential cuts, as many of them rely on Medicaid coverage pathways and services that are offered at state option. This issue brief describes the role that Medicaid plays for nonelderly adults with disabilities. The appendix table contains per enrollee spending and take-up of selected eligibility and service options relevant to nonelderly adults with disabilities by state.

The U.S. Census Bureau defines a disability as a limitation in vision, hearing, mobility, cognitive functioning, self-care, and/or independent living. Self-care includes activities such as bathing and dressing. Independent living includes the ability to move around the community, such as visiting a doctor’s office or going shopping. People with disabilities have a range of medical and long-term care needs as a result of functional limitations. They may need attendant care for help with getting out of bed, bathing, dressing, and eating; assistive technology such as power wheelchairs and speech generating devices; medical equipment and supplies; mental health counseling; and/or supportive services to maintain community-based housing or employment.

Among people who are working, nonelderly adults with disabilities are significantly less likely to have a job that offers health insurance compared to those without disabilities (Figure 2). Overall, nonelderly adults with disabilities are about half as likely to be working for pay than those without disabilities. The ability of nonelderly adults with disabilities to work likely is limited as a result of their greater health needs and functional limitations, although with appropriate supports, many people with disabilities can and do work. However, among those who are working, nonelderly adults with disabilities are significantly less likely to be working full-time and to have access to employer-sponsored health insurance.

Non-elderly adults with disabilities are significantly more likely to have Medicaid and significantly less likely to have private insurance than those without disabilities (Figure 3). Those with disabilities are about three times as likely to be covered by Medicaid and about half as likely to have private insurance compared to those without disabilities. These differences are influenced by the greater health needs of people with disabilities and the fact that they are less likely to have access to employer-sponsored coverage. Nonelderly adults with disabilities also are significantly less likely to be uninsured than those without disabilities, reflecting the important role that Medicaid plays in covering this population.

Some nonelderly adults with disabilities are eligible for Medicaid through the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, based solely on their low income, in the 32 states (including DC) that have adopted the expansion as of 2017.3 The ACA expands Medicaid eligibility to nearly all nonelderly adults with income up to 138% FPL ($16,643/year for an individual in 2017) without an asset limit and provides enhanced federal matching funds for states to cover this group.4 Although having a disability is not required to qualify for Medicaid under the ACA’s expansion or other poverty-related pathways, more than three in 10 (35%) Medicaid adults who are not working report that they have an disability or illness. People with disabilities may receive Medicaid as expansion adults while they are waiting for a disability determination, which can take a substantial amount of time, or they may have a disability that does not meet Supplemental Security Income (SSI) medical criteria but is nonetheless limiting, or they may not financially qualify for SSI.5 Some expansion adults with disabilities are working, and a recent study found that working-age adults with disabilities are significantly more likely to be employed if their state has adopted the Medicaid expansion, compared to states that have not expanded.6

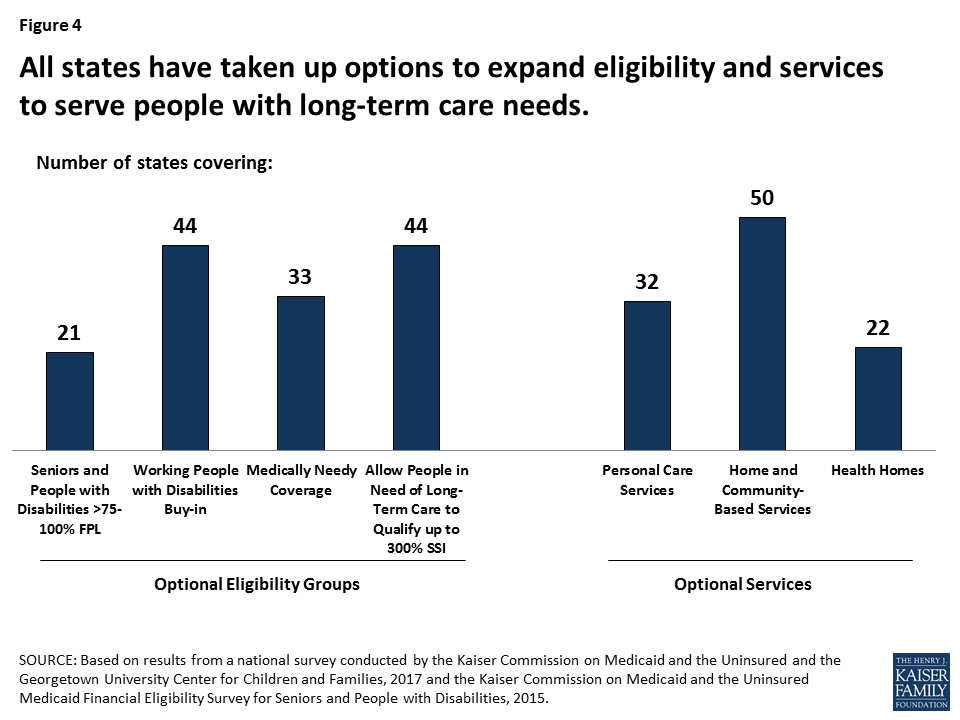

Some nonelderly adults with disabilities qualify for Medicaid through a disability-related pathway based on both their low income and functional limitations (Figure 4).7 All states generally must provide Medicaid to SSI beneficiaries, although this pathway does not include all people with disabilities. Only 36% of nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities receive SSI,8 meaning that nearly 2/3 of nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities qualify through another pathway. States can choose to extend Medicaid financial eligibility for people with disabilities up to 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $12,060 for an individual in 2017). In addition, states can expand financial eligibility for people who need long-term care services, in nursing homes and/or in the community, up to three times the SSI benefit rate (equivalent to 219% FPL or $26,460/year for an individual in 2017). States also can allow working people with disabilities at higher incomes to buy into Medicaid coverage by paying a premium. The disability-related pathways also generally have asset limits set by the state, which typically are at the SSI level of $2,000 for an individual.

Nonelderly adults with disabilities who receive Medicaid have very low incomes, with more than half living below the federal poverty level (Figure 5). Nearly 85% of nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities have incomes below 200% FPL (less than $24,120/year for an individual in 2017). Their low incomes reflect the fact that people with disabilities generally are poorer than those without disabilities as well as the low income eligibility limits associated with the Medicaid program. Nearly six in 10 nonelderly adults with disabilities receiving Medicaid are white, about one-quarter are black, and 16% are Hispanic. Just under three in 10 are between ages 55 to 64, and another three in 10 are between ages 45 to 54. About one-fifth are between ages 35 to 44, and one-quarter are ages 18 to 34.

Nonelderly adults with disabilities who receive Medicaid are significantly more likely to have multiple functional limitations compared to people with disabilities who have private insurance or those who are uninsured (Figure 6). About one-third of nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities have three or more functional limitations, more than two and one-half times the rate of privately insured nonelderly adults with disabilities and more than double the rate for those who are uninsured. By contrast, nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities are significantly less likely to have limited functioning in only one area compared to those who are privately insured. For an example of a Medicaid beneficiary with multiple functional limitations, see Nicholas’s story below.

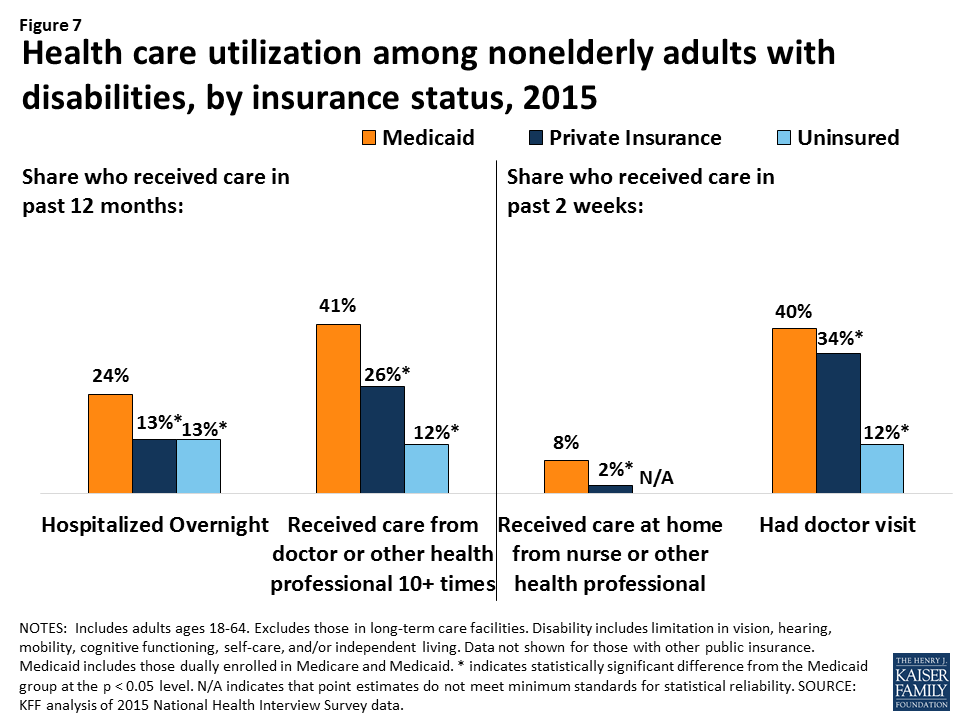

Nonelderly adults with disabilities receiving Medicaid are significantly more likely to use health care services than those with private insurance or those who are uninsured (Figure 7). They are four times as likely to receive nursing or other health care at home, nearly twice as likely to be hospitalized overnight, and more than one and one-half times as likely to have 10 or more health care visits in a year compared to those with private insurance. This increased utilization likely reflects their greater health needs and functional limitations as well as the fact that certain services, such as care at home, are more likely to be covered by Medicaid than by private insurance.

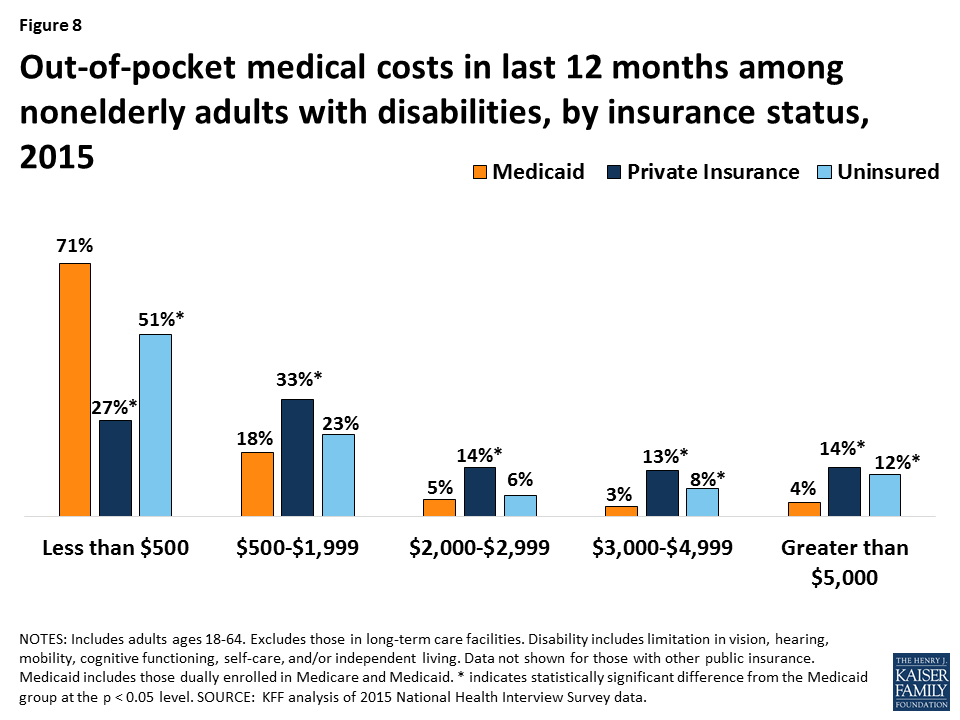

Nonelderly adults with disabilities receiving Medicaid are significantly more likely to have lower out-of-pocket medical costs compared to people with disabilities who are privately insured (Figure 8). Those with Medicaid are nearly three times as likely to incur costs of less than $500 per year compared to those with private insurance. Those with Medicaid also were more than three times less likely to have the highest out-of-pocket costs (more than $5,000/year) compared to those with private insurance. These differences are likely due to Medicaid’s cost-sharing rules, which are designed to protect people with low incomes from burdensome out-of-pocket costs, which can create financial barriers to receiving needed care. The lower out-of-pocket costs among people with Medicaid also reflect their low incomes. People with out-of-pocket medical expenses whose income exceeds Medicaid financial eligibility limits may become eligible for Medicaid through a “spend down’ by subtracting incurred medical expenses from their income.

Medicaid covers a broad range of medical and long-term care services to meet the diverse needs of nonelderly adults with disabilities (Figure 9). Through Medicaid, nonelderly adults with disabilities have access to regular preventive care as well as medical care for illnesses and chronic conditions. States must provide certain minimum services for adults, such as inpatient and outpatient hospital, physician, lab and x-ray, and nursing home services. States also can choose to provide a broad range of optional services, many of which are important to people with disabilities, such as prescription drugs, physical therapy, private duty nursing, personal care, rehabilitative services, and case management. Most home and community-based services (HCBS) are provided at state option.9

Medicaid provides long-term care services that support people with disabilities’ ability to live independently and safely in the community. Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term services and supports and plays a key role in helping states finance services to meet their community integration obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision.10 Many of these services are unavailable through private insurance, and they are too costly for people to afford out-of-pocket, especially given the low incomes of most people with disabilities. For example, Medicaid covers personal and attendant care services that assist people with disabilities with the tasks necessary for daily living, such as eating, bathing, dressing, preparing meals, and going grocery shopping.11 Medicaid also covers habilitative services that help people with disabilities learn independent living skills; assistive technology, such as lifts, wheelchairs, and speech-generating devices; supportive housing services that help people with disabilities obtain and retain community housing; and community-based mental health services, which help people with mental illness remain out of institutions. For an example of a Medicaid beneficiary relying on long-term mental health services, see Bill’s story below.

Medicaid covers services that enable people with disabilities to work. In addition to providing personal care and transportation services that help people with disabilities get ready for the day and get to work, states also can cover supported employment services, such as job coaching, to help people with disabilities work in the community.

The ACA offers states new and expanded options to provide community-based long-term care services. The ACA created the Community First Choice option to provided attendant care services and supports with 6% enhanced federal matching funds; eight states elect this option as of 2016. The ACA also expanded states’ ability to offer HCBS through the Section 1915 (i) option, which allows states to serve people with functional limitations that do not yet rise to an institutional level of care. This enables states to offer services in efforts to retain people in the community and prevent the need for costlier and more intensive services in the future. As of 2015, 17 states are using this option to provide targeted services to particular populations, such as people with mental health needs and those with I/DD. The ACA also created the Medicaid health homes option, which enables states to provide care coordination services for people with chronic conditions at a 90% enhanced federal match for the first two years; 22 states offer health homes as of 2016. For an example of a beneficiary receiving Medicaid community-based services, see Curtis’s story below.

Medicaid helps make coverage affordable for nonelderly adults with disabilities. Federal minimum standards limit Medicaid beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs to prevent them from encountering financial barriers to accessing necessary care. States can charge premiums to those with incomes above 150% FPL. Copayment levels vary based on income and generally are limited to nominal amounts for those below poverty. People who receive long-term care services, such as those in nursing homes, may be required to contribute most of their income toward the cost of their care, except for a small personal needs allowance to pay for items that Medicaid does not cover, such as clothing.

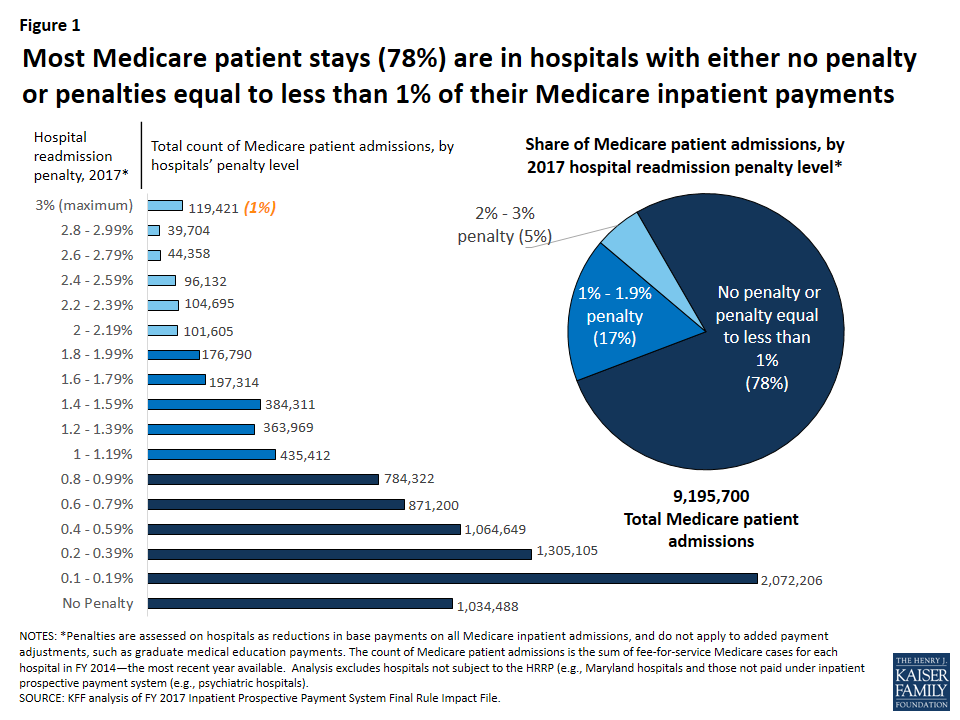

Medicaid spending on people with disabilities is disproportionate to their enrollment in the program (Figure 10). Unlike the data presented earlier in this paper, which are limited to nonelderly adults with disabilities, the Medicaid enrollment and spending data for people with disabilities in this section include both nonelderly adults and children with disabilities. As of 2011, people with disabilities accounted for 15% of total Medicaid enrollment but 42% of program spending. This discrepancy is likely due to their greater health needs and more intensive use of services compared to those without disabilities.

Per enrollee spending for people with disabilities is substantially higher than for those without disabilities (Figure 11). Per enrollee spending for people with disabilities totaled $16,643 in 2011, more than five times higher than for adults without disabilities ($3,247) and nearly seven times higher than for children without disabilities ($2,463). Some of this difference is due to people with disabilities’ greater use of both institutional and community-based long-term care services ($6,137) compared to those without disabilities, who have per enrollee long-term care spending at negligible amounts. This is because some people enrolled in Medicaid through a pathway based solely on their low income also have disabilities and use long-term care services. In addition to having higher per enrollee long-term care spending, people enrolled through a disability-related pathway also have higher per enrollee spending for acute care services ($10,505), more than eight times that of adults without disabilities ($3,234) and more than four times that of children without disabilities ($2,399).

Per enrollee spending for people with disabilities varies substantially by state, ranging from $10,142 in AL to $33,808 in NY in 2011 (Figure 12 and Appendix Table). Over half of states spend between $15,000 to $19,999 per enrollee for people with disabilities, and another third of states spend between $20,000 to $34,999 per enrollee for people with disabilities. This variation is due to state choices about eligibility and services, as many disability-related coverage pathways and most home and community-based long-term care services are offered at state option.

As of 2011, 80% of nonelderly people with disabilities who use Medicaid long-term care are served in the community, with the remaining 20% in institutions (Figure 13). Over the last several decades, states have made substantial progress in serving more nonelderly adults with disabilities in the community instead of in nursing homes. HCBS typically are less expensive than nursing homes and are preferred by many nonelderly adults with disabilities. However, state Medicaid programs must cover nursing home services, while nearly all HCBS are optional, making HCBS vulnerable to cuts if states are faced with funding reductions.

Medicaid covers more than three in 10 nonelderly adults with disabilities, providing a broad range of medical and long-term care services to meet their diverse needs and making coverage affordable. Over half of nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities live below the federal poverty level, and nearly 85% have incomes of less than 200% FPL, or $24,120 per year for an individual in 2017. They are significantly more likely to use health care services, including care at home, and to have lower out-of-pocket medical costs than nonelderly adults with disabilities who are privately insured, reflecting their lower incomes and greater functional limitations. Medicaid spending for this population is disproportionate to their program enrollment, due to their greater health needs and reliance on Medicaid for expensive but necessary services, especially long-term care in the community and nursing homes, that are generally unavailable through private insurance and too costly to afford out-of-pocket.

The American Health Care Act, as approved by the House Energy and Commerce Committee, would fundamentally change Medicaid’s financing structure to a per capita cap, resulting in an estimated $880 billion reduction in federal Medicaid spending from 2017 to 2026. People with disabilities may be especially affected by a per capita cap as most disability-related coverage pathways and many services important to people with disabilities, such as community-based long-term care, are provided at state option, making them subject to cuts if states are faced with federal funding reductions. States’ delivery system reform efforts that affect people with disabilities, such as those that seek to improve care coordination; integrate physical, behavioral health, and long-term care services; and serve more people in the community instead of institutions also could be curtailed if federal Medicaid funding is limited.

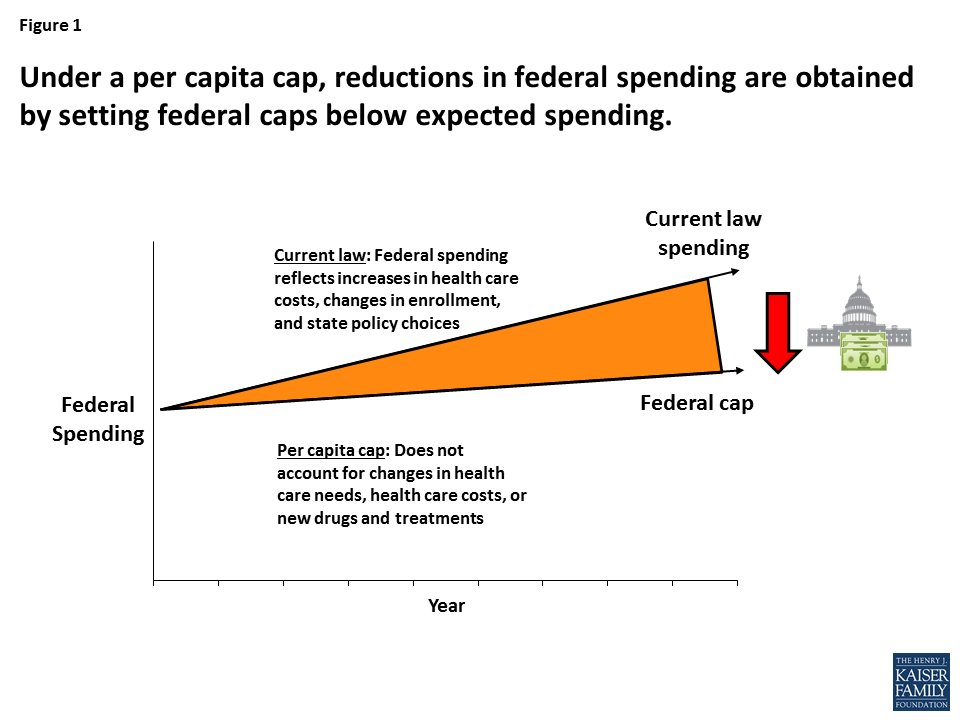

While per enrollee Medicaid spending for both acute and long-term care services is substantially higher for people with disabilities compared to those without disabilities, it also varies substantially across states. A per capita cap, as proposed in the American Health Care Act, could lock in historical state differences in scope of coverage and spending for people with disabilities. Changing Medicaid financing to a per capita cap also ties spending levels to a base year, which does not account for future spending increases due to new drug therapies or other medical advances yet to be developed, which could offer important new treatments to improve the lives and functioning of people with disabilities.

The American Health Care Act also ends enhanced federal funding for the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and the Community First Choice (CFC) option, both of which can be important to people with disabilities. The ACA’s Medicaid expansion provides a pathway through which some nonelderly adults with disabilities newly gained coverage, while CFC allows states to offer attendant care services and supports that help people with disabilities live and work in the community. As approved by the House Energy and Commerce Committee, the AHCA repeals the enhanced federal matching funds for the ACA’s expansion enrollees as of January 1, 2020, except for those enrolled as of December 31, 2019, who do not have a break in eligibility of more than one month, and ends the enhanced federal matching funds for CFC as of January 1, 2020. These reductions in federal funding could jeopardize states’ ability to continue to finance the expansion coverage pathway and Community First Choice services.

Unlike nursing home services which are required, many home and community-based services important to people with disabilities are provided through optional waivers, which put them at risk for cuts as states look for ways to limit spending in the face of substantial federal funding reductions. In addition, new flexibility granted to states under Section 1115 Medicaid expansion waivers could further complicate coverage for nonelderly adults with disabilities. Existing Medicaid expansion waivers include provisions not otherwise permitted under current Medicaid rules, such as premiums, copayments above statutory limits, healthy behavior incentives, and health savings accounts. People who are considered “medically frail” are exempt from some of these rules, which can create additional administrative burdens for states, health plans, and beneficiaries in making sure that people with disabilities are appropriately recognized.

Under a per capita cap and the elimination of enhanced federal financing as proposed in the AHCA, states will be faced with budgetary pressures resulting from the substantial reduction in federal Medicaid funds. At the same time, states will continue to be required to meet their community integration obligations for people with disabilities under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision. Medicaid has played a key role in financing community-based long-term care services, but its ability to continue to do so may be limited by the loss of the CFC enhanced funding for attendant care services, along with the broader reductions in federal Medicaid funds under a per capita cap, thereby increasing budgetary pressures on states. Because the AHCA could have significant consequences for enrollees and states, its potential implications warrant careful consideration for their impact on nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities.

| Appendix Table: State Medicaid Spending and Options for People with Disabilities | |||||||||||

| State | Medicaid Spending Per Enrollee(2011) | Share of Medicaid LTC SpendingDevoted to HCBS (FY 2014) | ACA Expans.(2017) | Optional Disability-Related Eligibility Pathways (2015) | Optional Home and Community-Based Services | ||||||

| >73%-100% FPL | Work Buy-In | LTC to 300% SSI | Pers’l Care(2013) | HCBS Waivers(2017) | CFC(2016) | Sec. 1915 (i)(2015) | Health Homes(2016) | ||||

| States with Republican Governor | |||||||||||

| Alabama | $10,142 | 42% | X | X | X | ||||||

| Arizona | $22,040 | 70% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Arkansas | $14,023 | 50% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Florida | $15,005 | 33% | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Georgia | $10,639 | 48% | X | X | X | ||||||

| Idaho | $21,781 | 53% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Illinois | $16,689 | 44% | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Indiana | $19,488 | 31% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Iowa | $20,242 | 50% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Kansas | $17,153 | 53% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Kentucky | $12,856 | 41% | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Maine | $16,920 | 55% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Maryland | $23,798 | 56% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Massachusetts | $16,927 | 57% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Michigan | $15,109 | 35% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Mississippi | $12,960 | 27% | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Missouri | $17,481 | 56% | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Nebraska | $17,449 | 49% | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Nevada | $15,706 | 49% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| New Hampshire | $21,545 | 50% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| New Jersey | $19,951 | 41% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| New Mexico | $18,500 | 74% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| North Dakota | $28,692 | 41% | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Ohio | $21,892 | 52% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Oklahoma | $15,010 | 44% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| South Carolina | $12,830 | 43% | X | X | X | ||||||

| South Dakota | $19,156 | 47% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Tennessee | $14,680 | 53% | X | X | |||||||

| Texas | $17,709 | 57% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Utah | $19,718 | 48% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Vermont | $17,789 | 68% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Wisconsin | $16,599 | 64% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Wyoming | $25,346 | 50% | X | X | X | ||||||

| TOTAL: 33 | N/A | N/A | 16 | 13 | 27 | 30 | 21 | 33 | 2 | 9 | 15 |

| States with Democratic or Independent Governor | |||||||||||

| Alaska | $28,790 | 70% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| California | $20,080 | 64% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Colorado | $19,643 | 63% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | $31,004 | 48% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Delaware | $22,972 | 42% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| DC | $28,604 | 53% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Hawaii | $17,035 | 42% | X | X | X | ||||||

| Louisiana | $15,099 | 39% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Minnesota | $26,890 | 75% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Montana | $16,352 | 57% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| New York | $33,808 | 58% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| North Carolina | $15,060 | n/a | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Oregon | $18,255 | 79% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Pennsylvania | $16,441 | 44% | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Rhode Island | $21,417 | 58% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Virginia | $18,952 | 55% | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Washington | $16,208 | 66% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| West Virginia | $12,993 | 48% | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| TOTAL: 18 | N/A | N/A | 16 | 8 | 17 | 14 | 11 | 18 | 6 | 8 | 7 |

| NOTES: Spending per enrollee includes full benefit nonelderly adults and children with disabilities only. Share of LTC spending devoted to HCBS omits managed care spending in CA and MA. % HCBS not calculated for NC due to missing data. Not all states electing the >73%-100% FPL expansion go up to 100% FPL. HCBS waivers include § 1915 (c) and § 1115.SOURCES: KFF, Data Note: Variation in Per Enrollee Medicaid Spending Across States (Feb. 2017); Steve Eiken, Kate Sredl, Brian Burwell, and Paul Saucier, Medicaid Expenditures for Long Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2014, Table C (Bethesda, MD: Truven Health Analytics, April 2016); KFF, Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision (Jan. 1, 2017). KFF, Medicaid Financial Eligibility for Seniors and People with Disabilities in 2015 (March 2016). KFF, Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Programs: 2013 Data Update (Oct. 2016). KFF, Medicaid Section 1115 Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Waivers: A Survey of Enrollment, Spending, and Program Policies (Jan. 2017). KFF, Section 1915 (k) Community First Choice State Plan Option (March 2016). KFF, Health Home State Plan Option (April 2016). | |||||||||||

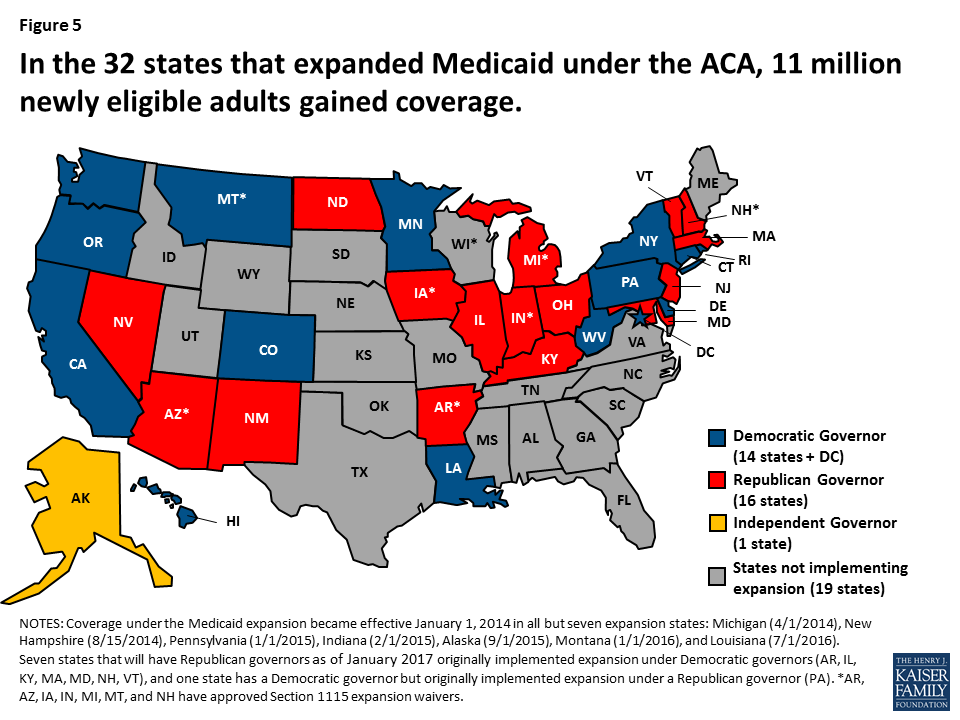

On March 9, the House Ways and Means Committee and Energy and Commerce Committee passed the American Health Care Act, the Republican leadership’s plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In fact, the legislation would make changes beyond the ACA, including major changes in the Medicaid program, which provides health coverage for 1 in 5 Americans. The House bill would cap federal funding for the more than 74 million low-income children, adults, seniors, and people with disabilities covered by Medicaid. It would also phase out enhanced federal funding for the 11 million adults newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA Medicaid expansion.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the House bill would reduce federal spending by $1.2 trillion over the period 2017-2026 and reduce the federal deficit by $337 billion. The total reduction in federal spending over the 2017-2026 period includes a reduction of $880 billion in federal spending for Medicaid. The reduction in federal Medicaid spending would be used to help finance the tax credits and the federal revenue reductions attributable to repeal of the ACA taxes provided by the House bill. By 2026, 14 million fewer people would be covered by Medicaid relative to the number expected under current law and number of uninsured people would increase by 21 million, reaching 52 million in 2026. This brief considers five key Medicaid implications of the House bill.

The 74 million individuals covered by the Medicaid program include many of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged people in our society. Among those served by the program are millions of low-income pregnant women, infants, children, and parents and other adults – most of them in working families. Millions of poor senior citizens and millions of low-income Americans of all ages with physical disabilities, developmental disabilities, chronic conditions, and serious mental illness also rely on Medicaid. The individuals and families covered by Medicaid lack access to other affordable health insurance because of their low income or health needs. Without Medicaid, nearly all of them would be uninsured or underinsured for health and long-term care they need.

Throughout the Medicaid program’s history, Medicaid costs and risks have been shared by states and the federal government. The guarantee of federal Medicaid matching funds with no pre-set limit expands states’ capacity to provide health coverage for their residents and helps them manage increases in Medicaid costs that are fueled by health care cost inflation, the emergence of expensive new treatments and drugs, and the aging of the population. Because states share the costs of Medicaid, they have strong incentives to run efficient and effective programs, and state cost-cutting measures taken in hard economic times, including reductions in provider payment, have led to lean Medicaid operations. Beginning in FY 2020, the House bill would cap federal Medicaid funding per enrollee to achieve federal savings, shifting costs to states (Figure 1). According to the CBO, under the House bill, federal Medicaid spending would fall by $880 billion over the period 2017-2026. In 2026, federal spending for Medicaid would be about 25% lower than expected under current law, and 14 million fewer people would be covered by Medicaid than expected under current law.

The bill would give states some flexibility to reduce costs by repealing the requirement that states provide the federally-defined essential health benefits for Medicaid expansion adults. However, it would also reduce states’ flexibility to maintain Medicaid eligibility and coverage at current levels.

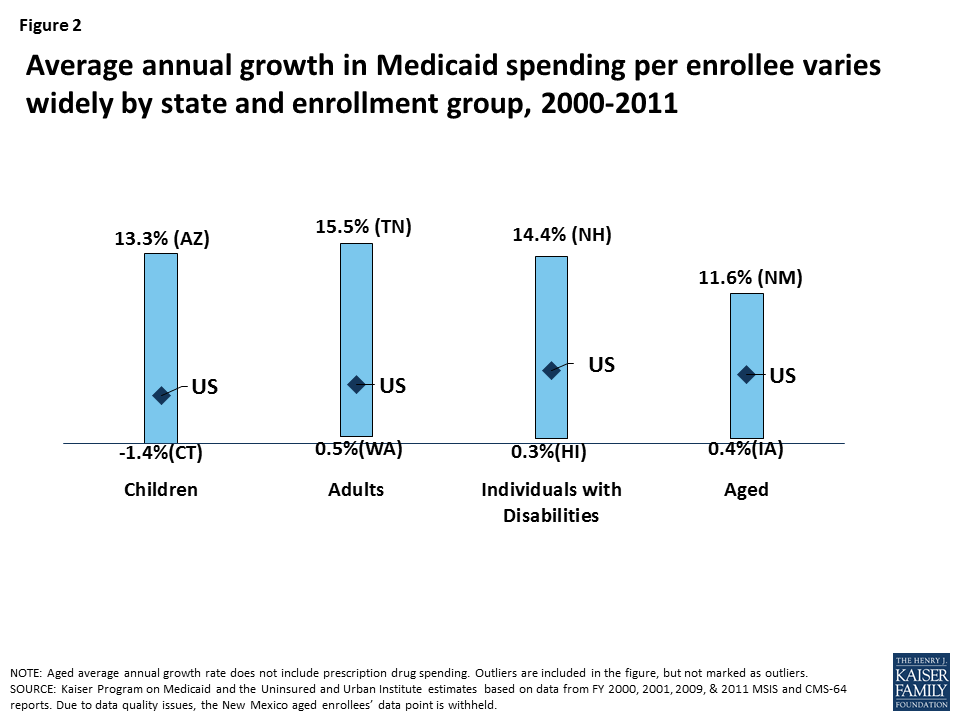

Medicaid spending per enrollee varies widely by state, by enrollment group, and over time (Figure 2). This variation stems from many factors, including demographic and health differences across states, variation in spending by enrollment group, local health care prices, and state Medicaid policy choices. The House bill would cap federal Medicaid funding per enrollee based on five groups: the elderly; individuals with disabilities; children; Medicaid expansion adults; and other adults. The federal per-enrollee caps would be based on states’ Medicaid expenditures in 2016, trended forward to 2019 by the medical CPI. Using a base year and a uniform index to establish the federal caps would lock states into their past Medicaid experience and omit consideration of substantial state variation in actual Medicaid per-enrollee spending growth. To illustrate, although Medicaid spending per child fell by 1.4% annually in Connecticut and grew by 13.3% annually in Arizona during the period 2000-2011, the federal cap per child would be determined in both states using the medical CPI, which is high compared to Connecticut’s actual experience and low compared to Arizona’s. This uniform approach would have differential impacts on states’ ability to address changing needs and new health challenges.

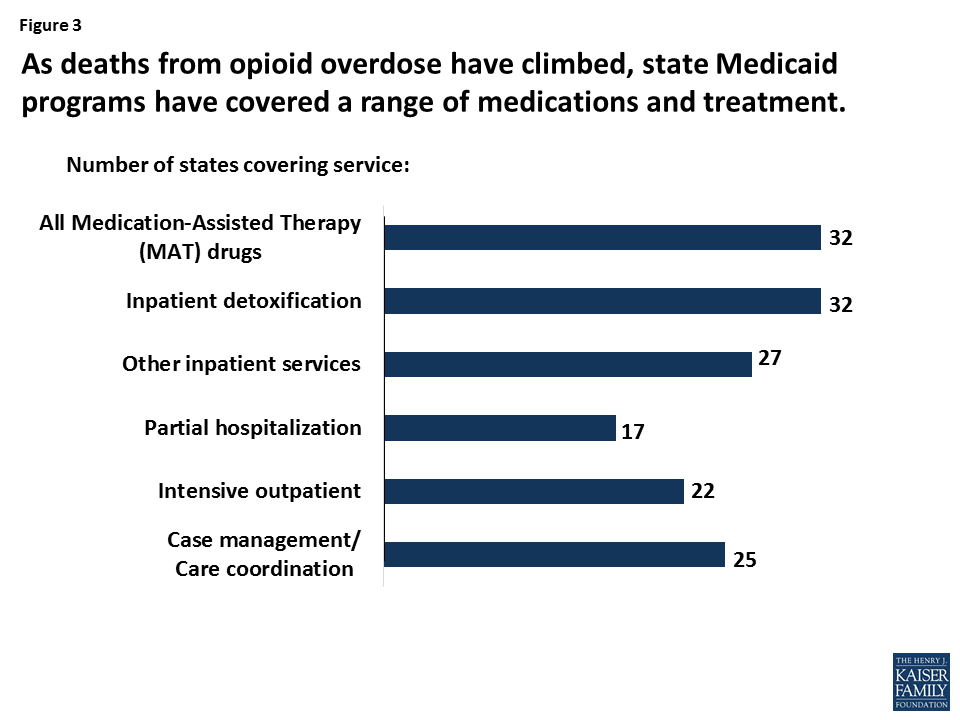

The availability of federal matching funds as needed helps states respond to changing coverage needs related to economic recessions; public health emergencies like HIV/AIDS and the opioid addiction epidemic; the growing numbers of the very old; disasters like 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina; and the emergence of new but costly treatments, like drugs for Hepatitis C (Figure 3). Converting to capped federal funding, as the House bill provides, would shift the risk for spending above the federal caps to states, increasing pressure on state budgets over time and likely leading to reduced coverage and access to care for low-income people, higher out-of-pocket costs, and increased uncompensated care costs for hospitals, clinics, doctors, nursing homes, and other providers.

In addition to providing health insurance for poor families, Medicaid is the nation’s predominant source of financing for long-term care, serving 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiaries and 2 in 5 people with disabilities. States have used their flexibility in Medicaid extensively to cover optional Medicaid groups and services to meet the long-term care needs of their residents, and a large share of their Medicaid spending is associated with these policy choices (Figure 4). Because of Medicaid, many people who would otherwise be in nursing homes are able to live independently and safely in the community. Under the House bill, states facing budget pressures might reconsider their optional expansions of Medicaid eligibility and services.

Medicaid provides health coverage for people who are poor or who have substantial health care needs but cannot afford private insurance or need more extensive benefits than it provides. Federal and state expansions of Medicaid and CHIP for children have led to a sharp decline in the uninsured rate for children, which fell from 14% in 1997 to an historic low of 5% in 2016. Following passage of the ACA, the nation experienced an unprecedented decline in the uninsured rate for nonelderly individuals, from 16.6% in 2013 to an all-time low of 10% in 2016. The 32 states – including 16 states with Republican Governors – that adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion to adults led the declines.

With enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion, states have been able to provide coverage for millions of uninsured adults, including many with chronic physical and mental illnesses; the Medicaid expansion has also been instrumental to states’ ability to respond to the opioid addiction epidemic. The House bill would end the enhanced federal funding for the expansion population in 2020, which would place substantial budget pressures on states to maintain coverage, or lead the uninsured rate to climb if states are unable to shoulder these additional costs alone. CBO’s report on the House bill estimates that federal spending for Medicaid would drop by $880 billion over the 2017-2026 period due to capped federal Medicaid funding and the termination of enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion. By 2026, an estimated 14 million fewer people would be covered by Medicaid relative to the number expected under current law, and number of uninsured people would rise to 52 million – an increase of 21 million over 2017.

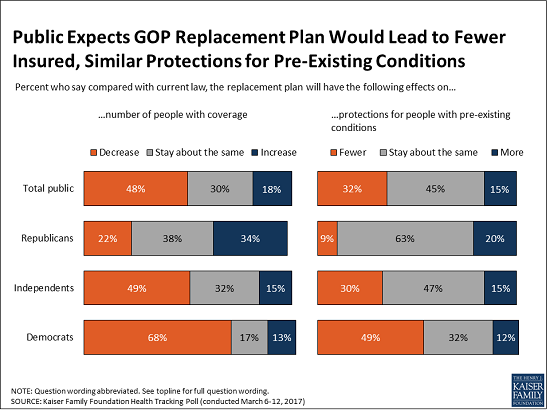

Fielded March 6-12 as Americans were first learning about the American Health Care Act and before the Congressional Budget Office estimated its effects, the latest Kaiser Tracking Poll shows that large shares of the public expect the House Republican health care plan would result in fewer people having health insurance and higher costs for people who buy their own health insurance. Republicans are generally more likely to expect positive results from the plan while Democrats and independents are more likely to foresee negative ones.

About half (48%) of the public say the plan would result in fewer people having health insurance, compared to one in five (18%) who say it would increase the number of people with coverage.

Nearly half (45%) say protections for people with pre-existing conditions would stay about the same. Roughly a third (32%) say the replacement plan would weaken protections for people with pre-existing conditions, about twice the share who say it would increase protections (15%).

The poll finds the public starts out skeptical of the potential effects of the Republican bill on costs for people who buy their own health insurance on the individual market, one of the groups most affected by Obamacare:

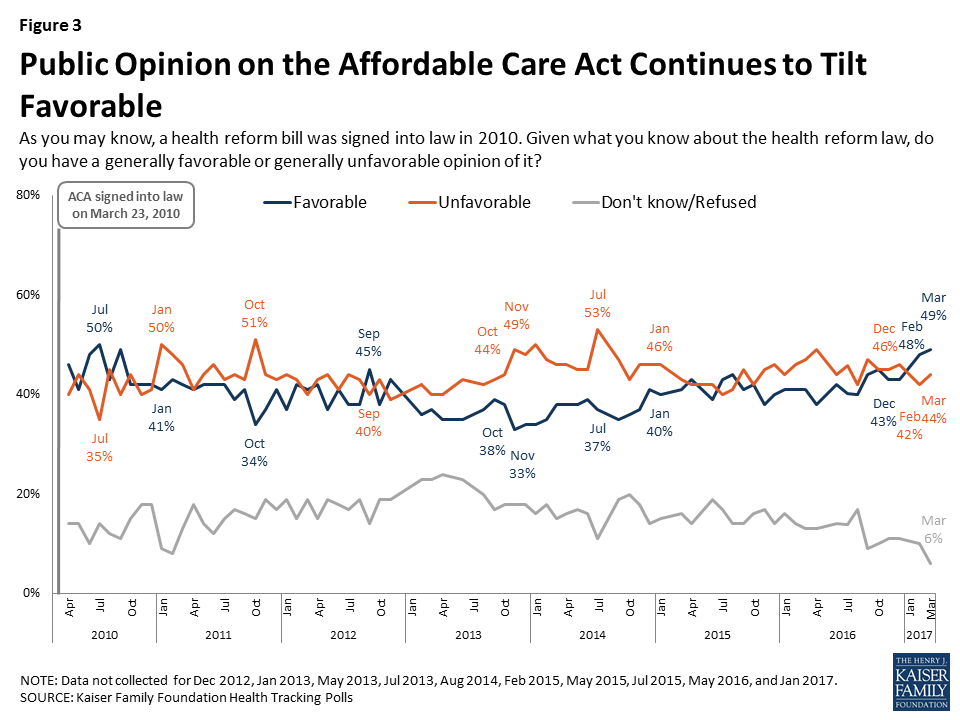

Public Remains Split on the ACA and its Repeal

Overall, the public remains divided on whether Congress should (45%) or should not (51%) repeal the Affordable Care Act at all. Among those who favor repeal, more want Congress to wait until the details of a replacement plan are known (24% overall) than want an immediate vote (19%).

Views of the Affordable Care Act overall are similar to last month, with 49 percent holding a favorable view and 44 percent unfavorable. As in the past, there are huge partisan divisions, with Democrats largely holding favorable views and Republicans largely holding unfavorable ones.

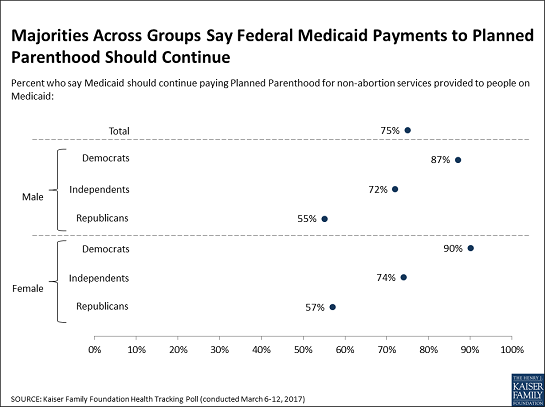

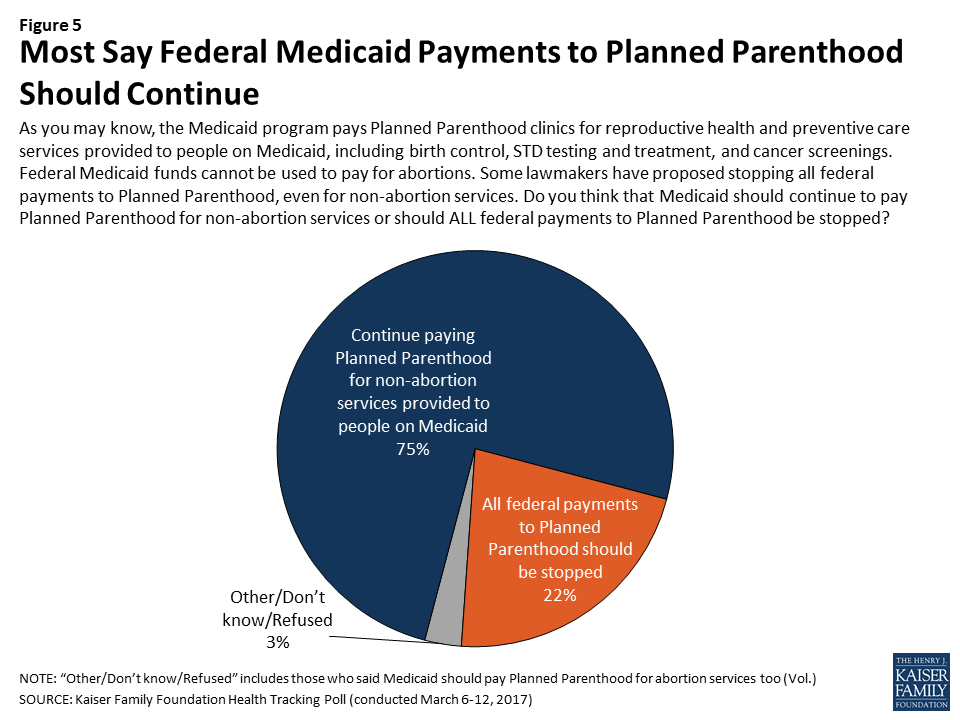

Large Majority Supports Continued Medicaid Funding to Planned Parenthood for Covered Services

The House replacement bill includes a provision that would prohibit federal funding for Planned Parenthood clinics for one year for all Medicaid services they provide, including contraception, testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases and cancer screenings.

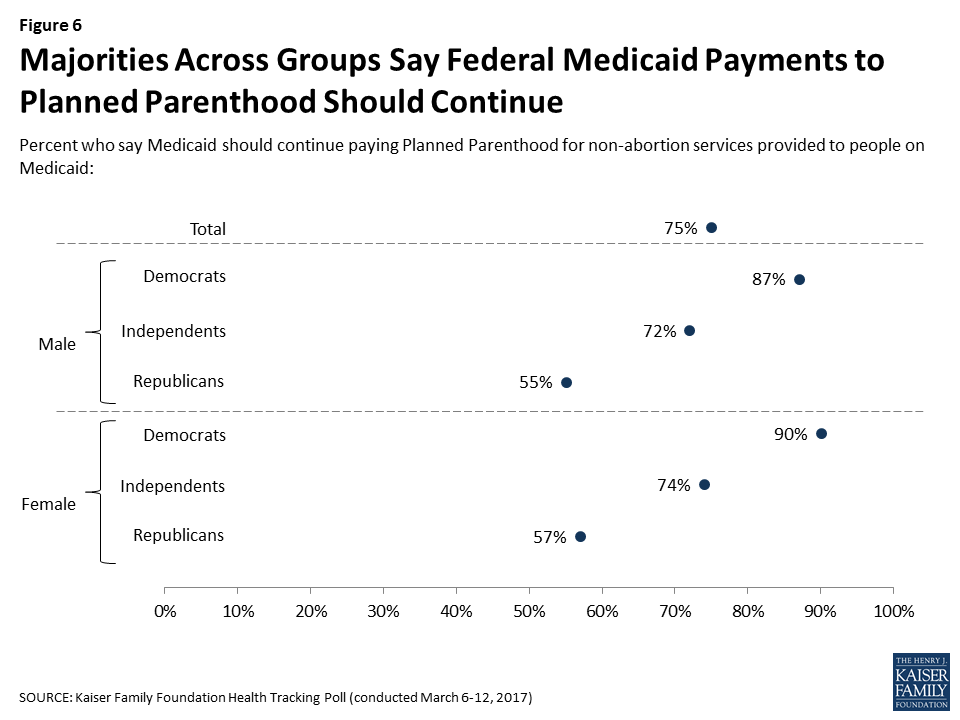

Three quarters (75%) of the public oppose cutting off federal funds to Planned Parenthood for providing these services, while 22 percent favor it. Substantial majorities of Democrats and independents as well as narrower majorities of Republican men (55%) and Republican women (57%) oppose cutting off funding. Relatively few people change their minds when presented with counterarguments to their initial view.

At least two thirds of Americans also report being aware of the range of services Planned Parenthood provides, including contraception (87%), testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases (80%), cancer screenings and preventive services (68%), and abortion (68%). In contrast, about one third (33%) of the public is aware that there is already a ban on using federal Medicaid funds to pay for abortions.

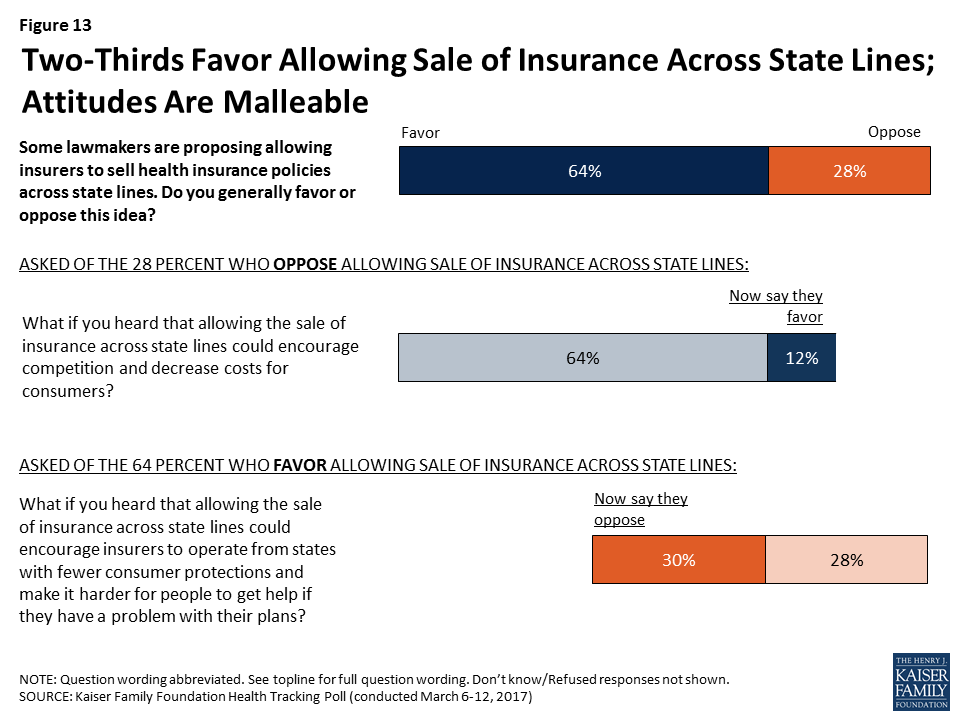

Majority Favors Allowing the Sale of Insurance Across State Lines, Though Views Are Malleable

President Trump and Republican leaders in Congress have supported the idea of allowing insurers to sell their plans across state lines as a way to drive down insurance costs, though this provision is not included in the current House legislation. The poll finds two thirds of the public (64%) generally favor this provision, compared to about three in 10 (28%) who oppose it. However, substantial shares of those who support or oppose the provisions change their minds when presented with counterarguments.

For instance, about half of those who originally supported the provision change to oppose it (bringing total opposition to 57%) after hearing that it could encourage insurers to operate from states with fewer consumer protections and make it harder for consumers to get help if they have a problem. Similarly, about four in 10 of those who initially opposed the provision switch to support it (bringing total support to 78%) after hearing it could encourage competition and decrease costs for consumers.

Designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation, the poll was conducted from March 6-12 among a nationally representative random digit dial telephone sample of 1,206 adults. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish by landline (421) and cell phone (785). The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points for the full sample. For results based on subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher.

On March 6, 2017, House Republicans announced their plan to replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – the American Health Care Act (AHCA). While Americans are still learning about the details of this plan, the latest Kaiser Health Tracking Poll (which was in the field before the Congressional Budget Office released its analysis of the plan) examines the public’s first impressions of its likely effects on the number of uninsured, those who buy insurance on their own, and those with pre-existing conditions.

About half (48 percent) the public thinks the Republican replacement plan will decrease the number of people who have health insurance, while one in five (18 percent) say the number of insured people will increase and three in ten say it will stay about the same. Notably, the public is confused about the effect the current health care law has had on coverage rates in the U.S.; while four in ten (41 percent) know that the share of people who are uninsured has decreased since the ACA was passed, nearly as many (31 percent) believe it has increased and 26 percent think it has remained about the same.

When it comes to costs, about half (48 percent) expect the new plan to increase costs for people who buy insurance on their own, while about a quarter each say costs for these people will decrease (23 percent) or stay about the same (25 percent). Similarly, four in ten (41 percent) expect the replacement plan to provide health insurance with higher deductibles, while a quarter each think deductibles will decrease (25 percent) or stay the same (23 percent). When it comes to protections for people with pre-existing conditions, nearly half the public (45 percent) expects the replacement plan would provide similar protections to the current law, but about twice as many say the plan would offer fewer protections as say it would offer more (32 percent versus 15 percent).

Not surprisingly, partisans hold very different views of how the replacement plan would impact coverage and costs. While majorities of Democrats believe the plan will decrease the number of people with insurance and increase costs, Republicans’ views are more mixed. Nearly half of Republicans (46 percent) think the plan will decrease costs for people who buy their own insurance, four in ten (41 percent) think it will provide insurance with lower deductibles, and one-third (34 percent) think it will increase the number of people with health insurance.

| Table 1: Partisan Views on Likely Effects of Republican ACA Replacement Plan | ||||

Percent who say in general, compared to the current health care law, the replacement plan will…

| Total Public | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| …decrease the number of people with health insurance | 48% | 68% | 49% | 22% |

| …increase the number of pople with health insurance | 18 | 13 | 15 | 34 |

| …not change the number of people with insurance | 30 | 17 | 32 | 38 |

| …increase costs for people who buy their own insurance | 48 | 71 | 47 | 19 |

| …decrease costs for people who buy their own insurance | 23 | 6 | 25 | 46 |

| …not change costs for people who buy their own insurance | 25 | 20 | 26 | 28 |

| …provide insurance with higher deductibles | 41 | 60 | 41 | 16 |

| …provide insurance with lower deductibles | 25 | 13 | 26 | 41 |

| …provide insurance with about the same deductibles | 23 | 17 | 23 | 29 |

| …provide fewer protections for people with pre-existing conditions | 32 | 49 | 30 | 9 |

| …provide more protections for people with pre-existing conditions | 15 | 12 | 15 | 20 |

| …provide about the same protections for people with pre-existing conditions | 45 | 32 | 47 | 63 |

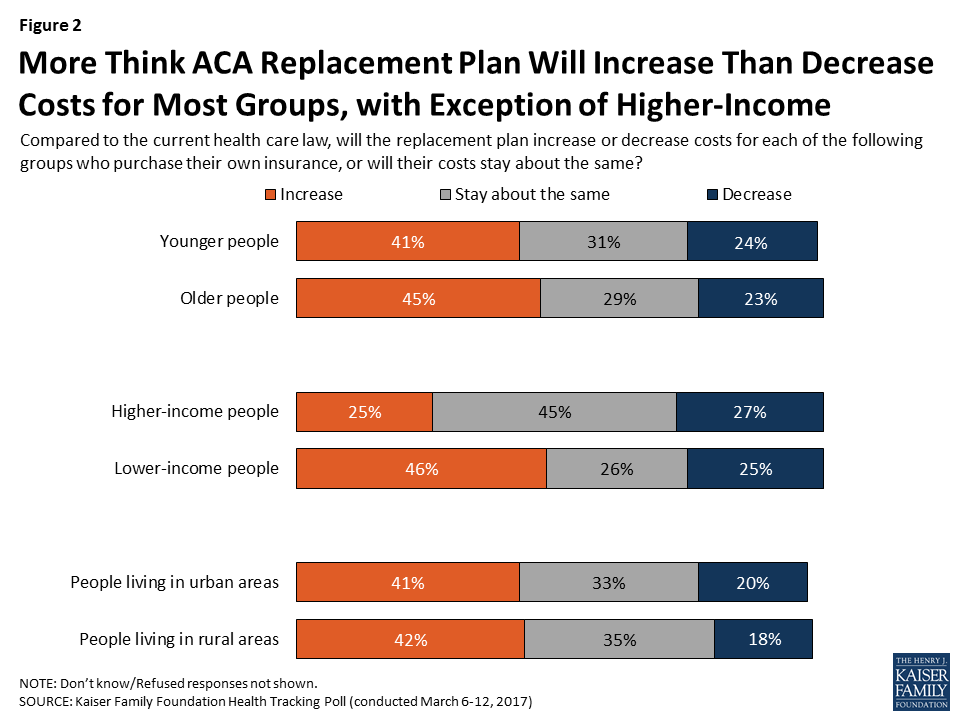

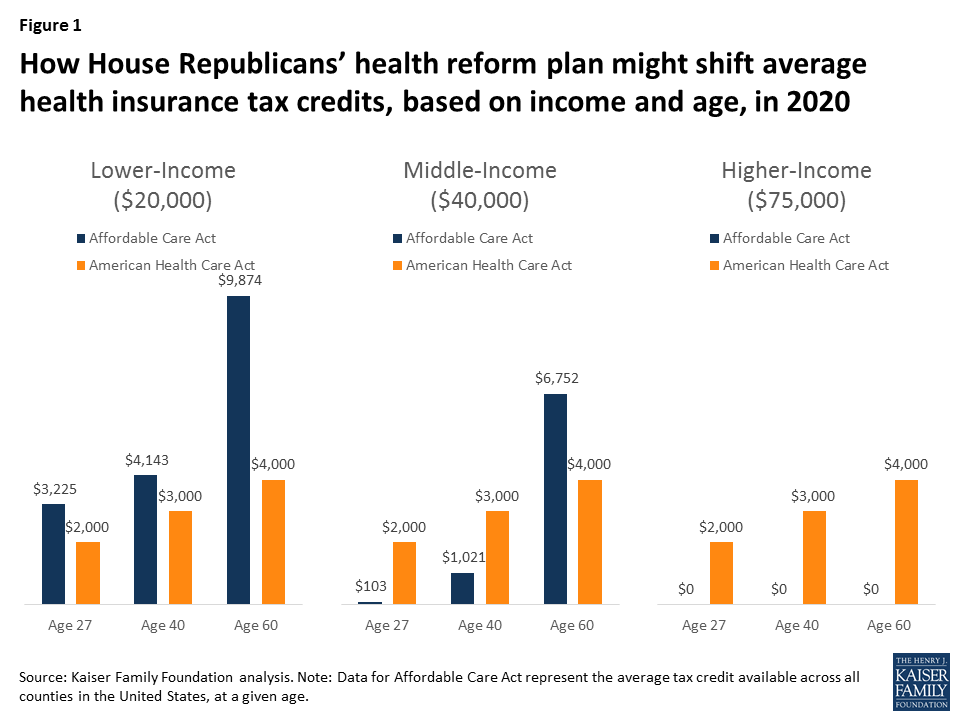

A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis has shown that the tax credit structure under the replacement plan would generally increase costs for certain groups of people buying insurance in the non-group market and decrease costs for others. For example, compared with current law, lower-income individuals, older adults, and those living in rural areas would pay more for insurance on average under the replacement plan, while younger adults, those with higher incomes, and those living in urban areas would pay less.1

However, the public does not see a distinction in how the replacement plan would impact costs for these different groups of individuals, except when it comes to income. About four in ten Americans expect costs to increase for younger, older, urban-dwelling, and rural-dwelling people buying insurance on the individual market, while between about two in ten and one quarter expect them to decrease. Similarly, almost half (46 percent) think costs would increase for lower-income people buying their own insurance, while one quarter think they would decrease. Views are more divided on how higher-income people buying their own insurance would be affected, with over four in ten (45 percent) saying their costs would be about the same, and about a quarter each saying they would increase (25 percent) or decrease (27 percent).

These views of the replacement plan are set against a backdrop of a public that continues to be divided in its view of the ACA. After shifting in a more favorable direction last month, public opinion on the current health care law mostly holds steady this month, with 49 percent having a favorable view and 44 percent unfavorable. Partisanship continues to underlie these views, with 77 percent of Republicans expressing an unfavorable view, 73 percent of Democrats expressing a favorable one, and independents evenly divided (46 percent favorable, 47 percent unfavorable).

The public also remains divided in their views of repeal, with half (51 percent) saying lawmakers should not vote to repeal the law and 45 percent saying they should vote to repeal it. Of those who want to see Congress vote to repeal the law, more say they want lawmakers to wait to vote to repeal the law until the details of a replacement plan have been worked out (24 percent) than say Congress should vote to repeal the law immediately and work out the details of a replacement plan later (19 percent).

Again, these views are largely driven by party identification, with the vast majority of Republicans (81 percent) saying Congress should vote to repeal the law and a similar share of Democrats (78 percent) saying they do not want the law repealed. Republicans are about evenly divided between those who want Congress to wait to vote on repeal until the details of a replacement plan have been worked out (41 percent) and those who say they should vote to repeal the ACA immediately and work out the details of a replacement plan later (36 percent).

| Table 2: Next Steps for the ACA | ||||

Percent who would like to see lawmakers do each of the following with the 2010 health care law:

| Total | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| Should not vote to repeal | 51% | 78% | 50% | 14% |

| Should vote to repeal (NET) | 45 | 19 | 46 | 81 |

| Wait to vote to repeal the law until the details of a replacement plan have been announced | 24 | 9 | 29 | 41 |

| Vote to repeal the law immediately and work out the details of a replacement plan later | 19 | 10 | 15 | 36 |

The House replacement bill includes a provision that would block Planned Parenthood for one year from receiving federal funds to provide services to low-income people on Medicaid, including non-abortion services like contraception, testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, and cancer screenings. Seventy-five percent of the public thinks Medicaid should continue to pay Planned Parenthood for non-abortion services, while 22 percent think all federal payments to the organization should be stopped.

While there are partisan and gender differences on this question, majorities across groups, including just over half of Republican men (55 percent) and Republican women (57 percent) say that the federal government should continue to pay Planned Parenthood for non-abortion services received by people on Medicaid.

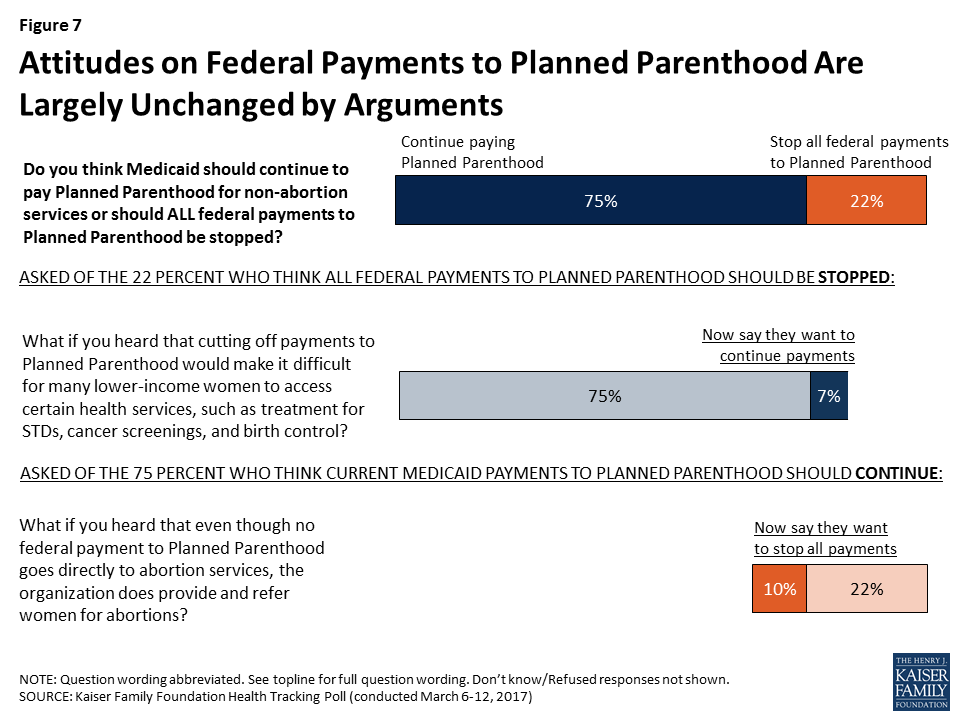

Americans’ attitudes towards federal payments to Planned Parenthood through the Medicaid program are largely stable, with few being persuaded from their opinions after hearing arguments for and against continued funding. Among those who think all federal Medicaid payments to Planned Parenthood should be stopped, about one-third (7 percent of the public overall) change their mind after hearing that this would make it difficult for many lower-income women to access certain health services, including treatment for sexually transmitted infections, cancer screenings, and birth control. On the other hand, a small share of those who initially support continuing current federal Medicaid payments to Planned Parenthood (10 percent overall) shift their opinion to oppose these payments after hearing that even though no federal funding goes directly to abortion services, Planned Parenthood does provide and refer women for abortions.

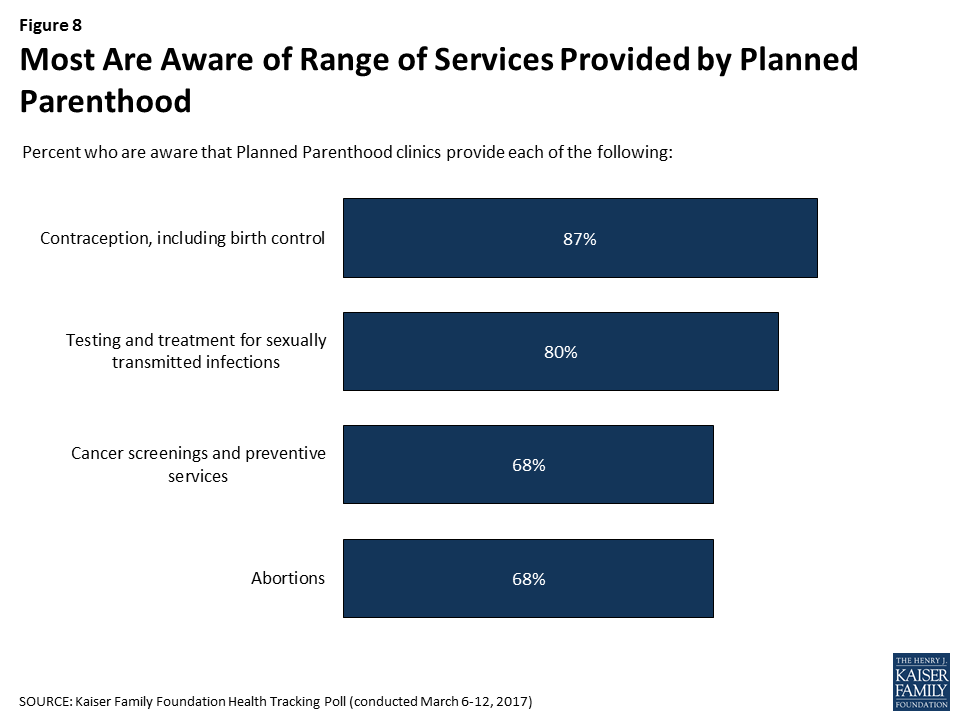

When asked about services currently provided by Planned Parenthood, most are aware of the variety of health care services provided by the organization including contraception (87 percent), treatment and testing for sexually transmitted infections (80 percent), cancer screenings (68 percent), and abortions (68 percent). Similar shares of women and men are aware that Planned Parenthood provides each of these services.

Awareness is lower when it comes to the question of whether federal funds can be used to pay for abortion services. While the Hyde Amendment currently prohibits federal Medicaid funds from being used to pay for abortions, just one-third (33 percent) of the public is aware of this ban, while almost half (45 percent) say there is not a ban and one in five (21 percent) say they don’t know.

Republicans are less likely than Democrats to be aware that there is a ban on federal funds being used to pay for abortions. One-quarter of Republican women (25 percent) and Republican men (26 percent) are aware of the ban, compared with about four in ten women and about a third of men who identify as Democrats and independents.

Beyond the question of federal funding for Planned Parenthood, more generally, a majority of the public says it is important that the federal government provides funding for reproductive health services including family planning and birth control for lower-income women. While a large majority of Democrats (84 percent) and over half of independents (56 percent) say this is “very” important, the share is much smaller among Republicans (36 percent).

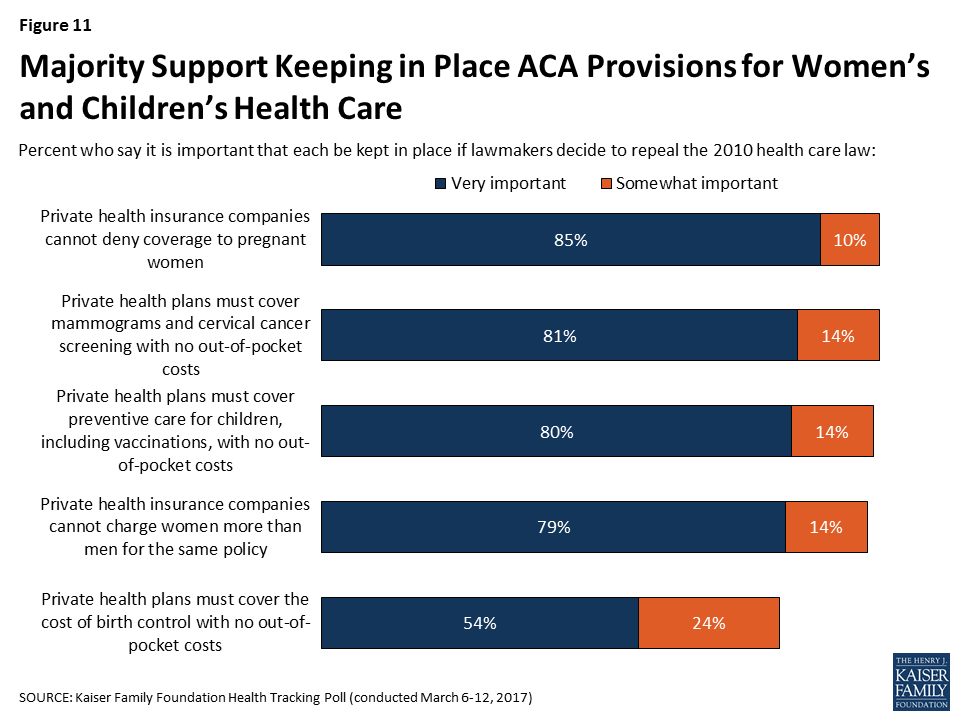

Large majorities of the public also say it is important (either “very” or “somewhat”) for several of the ACA’s requirements affecting women and children to be kept in place in any replacement plan. Roughly eight in ten say that if lawmakers decide to repeal and replace the 2010 health care law, it is “very” important that insurance companies cannot deny coverage to pregnant women (85 percent), that all private health plans must cover the full cost of preventive care with no cost-sharing for women (81 percent) and children (80 percent), and that insurance companies cannot charge women more than men for the same policy (79 percent). Fewer – 54 percent – say it is very important to keep in place the requirement for health plans to provide birth control with no cost-sharing, but three-quarters (78 percent) say this is at least “somewhat” important.

Large majorities of women, regardless of political party, say keeping most of these requirements in place is very important. One exception is the requirement that private health plans cover the cost of birth control with no cost-sharing, which majorities of women who are Democrats and independents view as very important compared with a smaller share of Republican women (38 percent). Men’s views are more divided by partisanship, with substantially higher shares of men who identify as Democrats saying each requirement is very important compared with Republican men. Three in ten Republican men (31 percent) say it is very important that the requirement for private health plans to cover the full cost of birth control is kept in place if the ACA is repealed.

| Table 3: Strong Support for Keeping in Place ACA Provisions Aimed at Women’s Health Services | |||||||

| Male | Female | ||||||

| Dems | Inds | Reps | Dems | Inds | Reps | ||

| Percent who say it is very important to them that each of the following requirements be kept in place if lawmakers decide to repeal the 2010 health care law: | |||||||

| Private health insurance companies cannot deny coverage to pregnant women | 92% | 78% | 72% | 97% | 85% | 80% | |

| Private health plans must cover mammograms and cervical cancer screenings with no out-of-pocket costs | 91 | 73 | 54 | 94 | 84 | 77 | |

| Private health plans must cover preventive care for children, including vaccinations, with no out-of-pocket costs | 90 | 74 | 57 | 94 | 84 | 73 | |

| Private health insurance companies cannot charge women more than men for the same policy | 83 | 73 | 59 | 92 | 83 | 81 | |

| Private health plans must cover the cost of birth control with no out-of-pocket costs | 62 | 39 | 31 | 79 | 57 | 38 | |

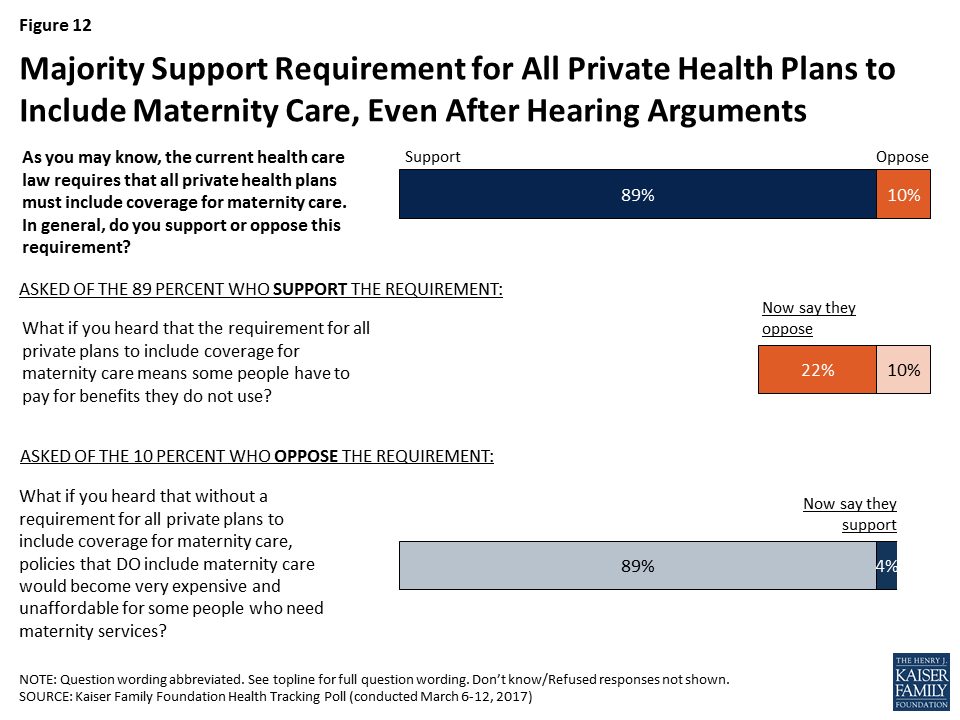

A large majority of the public (89 percent) also supports the ACA’s requirement that all private health plans must include coverage for maternity care, including 86 percent of Republicans and 94 percent of Democrats.

Views on this requirement are somewhat malleable. When those who initially support the requirement are read the argument that it means some people have to pay for benefits they do not use, about a quarter (22 percent of the public overall) change their mind so that 31 percent overall oppose the requirement. Still, a solid majority of 65 percent continues to support the requirement for all private health plans to include coverage for maternity care after this argument is read.

President Trump and Republican leaders in Congress have supported the idea of allowing insurers to sell their plans across state lines as a way to drive down insurance costs, though this provision is not included in the current House repeal and replace legislation.2 Overall, nearly two-thirds of Americans (64 percent) generally favor this proposal while three in ten (28 percent) oppose it. These attitudes are fairly malleable with both those who favor and oppose this policy being persuaded after hearing counter-messages.

Among the 28 percent who originally oppose this policy, four in ten (12 percent of the public overall) change their opinion after hearing that allowing the sale of insurance across state lines could encourage competition and decrease costs for consumers, increasing the total share who favor the policy to 76 percent.

On the other side, among the 64 percent who originally said they favor the policy, about half (30 percent of the public overall) change their opinion after hearing the argument that allowing the sale of insurance across state lines could encourage insurers to operate from states with fewer consumer protections and make it harder for people to get help if they have a problem with their plans, increasing the total share who oppose selling insurance across state lines to 57 percent.

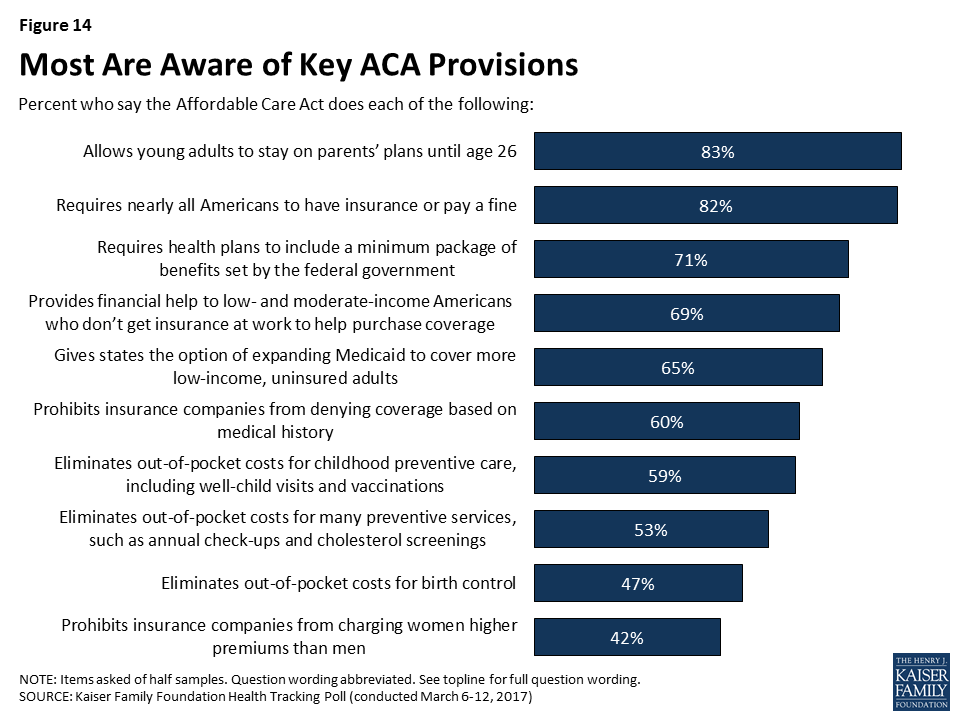

As the focus of debate moves away from the ACA itself and on to potential replacement plans, the public’s awareness of what the 2010 health care law actually does is somewhat uneven. While large majorities are aware of many of the ACA’s key provisions, others are less well-known. A large majority of the public is aware that the ACA allows young adults to stay on their parents’ insurance until age 26 (83 percent) and that it requires nearly all Americans to have health insurance or pay a fine (82 percent). Between six and seven in ten are aware the law requires insurance plans purchased by individuals to include a minimum package of benefits (71 percent), that it provides financial help to low-and moderate-income Americans who do not get coverage through an employer (69 percent), that it gives states the option of expanding Medicaid (65 percent), that it prohibits insurers from denying coverage to those with pre-existing conditions (60 percent), and that it requires health insurance plans to cover the cost of children’s preventive services, including immunizations, with no cost-sharing (59 percent).

Smaller shares – about half the public – know that the law eliminates out-of-pocket costs for preventive health care services (53 percent) and birth control (47 percent). Fewer still – 42 percent – are aware that the law prohibits insurance companies from charging women more than men.

At the same time, misconceptions about the law remain. Half (50 percent) incorrectly believe the ACA allows undocumented immigrants to receive financial help from the government to buy health insurance, and four in ten (40 percent) mistakenly think it cuts benefits for people in the traditional Medicare program.

This Kaiser Health Tracking Poll was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The survey was conducted March 6-12, 2017, among a nationally representative random digit dial telephone sample of 1,206 adults ages 18 and older, living in the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). Computer-assisted telephone interviews conducted by landline (421) and cell phone (785, including 465 who had no landline telephone) were carried out in English and Spanish by Princeton Data Source under the direction of Princeton Survey Research Associates International (PSRAI). Both the random digit dial landline and cell phone samples were provided by Survey Sampling International, LLC. For the landline sample, respondents were selected by asking for the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the opposite gender. For the cell phone sample, interviews were conducted with the adult who answered the phone. KFF paid for all costs associated with the survey.

The combined landline and cell phone sample was weighted to balance the sample demographics to match estimates for the national population using data from the Census Bureau’s 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) on sex, age, education, race, Hispanic origin, and region along with data from the 2010 Census on population density. The sample was also weighted to match current patterns of telephone use using data from the January-June 2016 National Health Interview Survey. The weight takes into account the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection in the combined sample and also adjusts for the household size for the landline sample. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total | 1206 | ±3 percentage points |

| Half Sample A | 609 | ±5 percentage points |

| Half Sample B | 597 | ±5 percentage points |

| Party Identification | ||

| Democrats | 437 | ±6 percentage points |

| Republicans | 285 | ±7 percentage points |

| Independents | 377 | ±6 percentage points |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 616 | ±5 percentage points |

| Female | 590 | ±5 percentage points |

Note: As of May 4, 2017, the American Health Care Act would allow states to waive certain consumer protections, including essential health benefits, community rating and age rating. If a state takes up such a waiver, the premium amounts for that state in this brief would no longer be applicable. For example, enrollee costs could depend on their health status, with healthy people paying less and sicker people or those with pre-existing conditions paying more.

An important part of the repeal and replacement discussions around the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will involve the type and amount of subsidies that people get to help them afford health insurance. This is particularly important for lower and moderate income individuals who do not have access to coverage at work and must purchase coverage directly.

The ACA provides three types of financial assistance to help people afford health coverage: Medicaid expansion for those with incomes below 138% of poverty (the Supreme Court later ruled this to be at state option); refundable premium tax credits for people with incomes from 100% to 400% of the poverty level who purchase coverage through federal or state marketplaces; cost-sharing subsidies for people with incomes from 100% to 250% of poverty to provide lower deductibles and copays when purchasing silver plans in a marketplace.

This analysis focuses on alternative ways to provide premium assistance for people purchasing individual market coverage, explaining how they work, providing examples of how they’re calculated, and presenting estimates of how assistance overall would change for current ACA marketplace enrollees. Issues relating to changing Medicaid or methods of subsidizing cost-sharing will be addressed in other analyses.

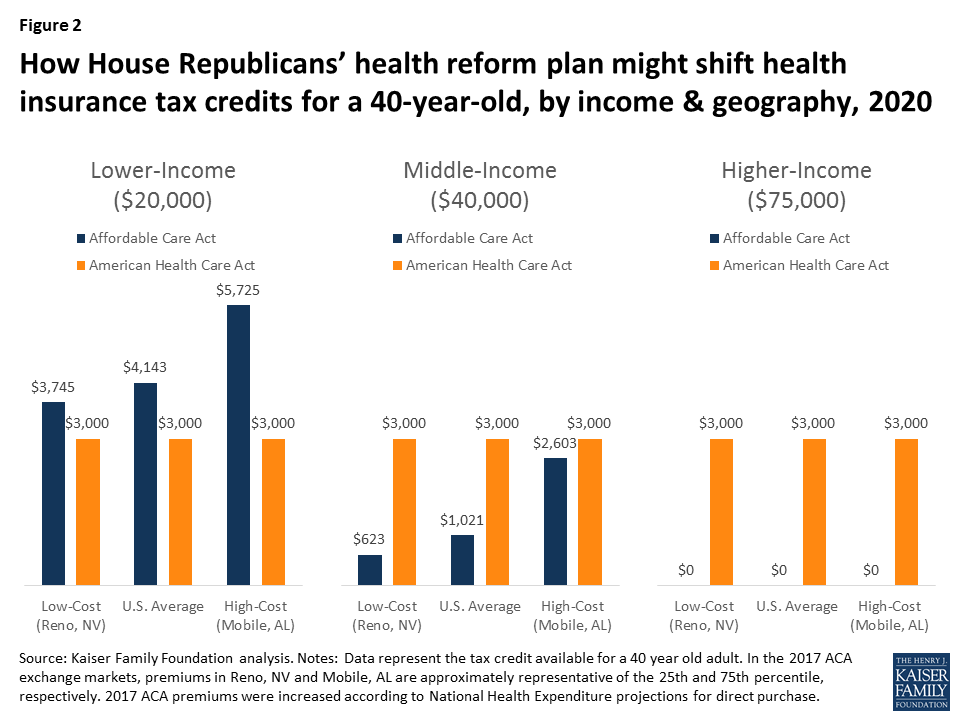

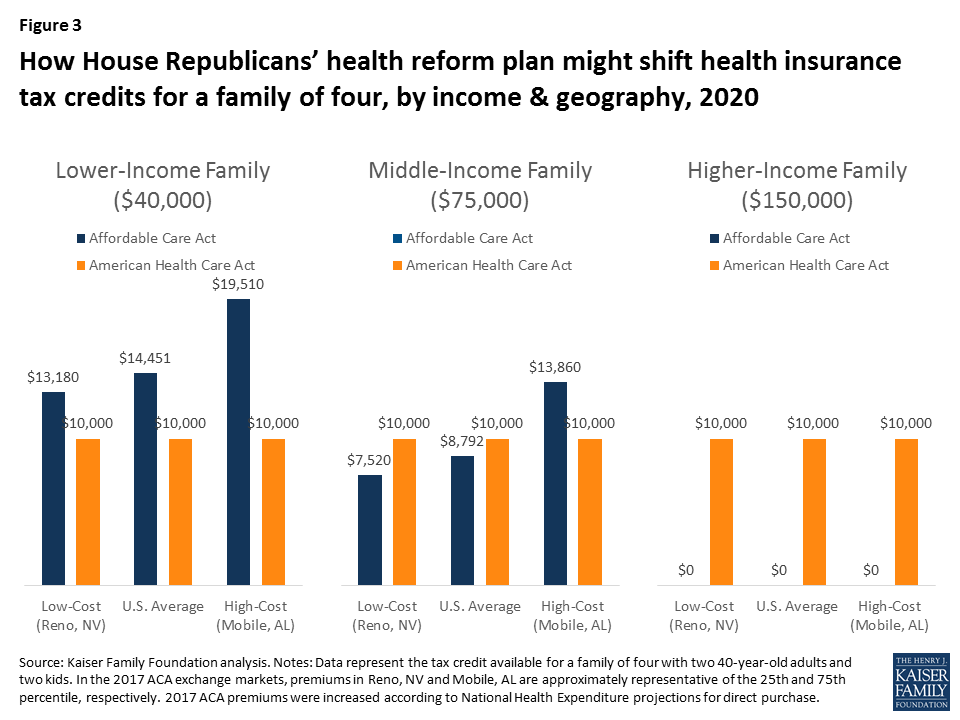

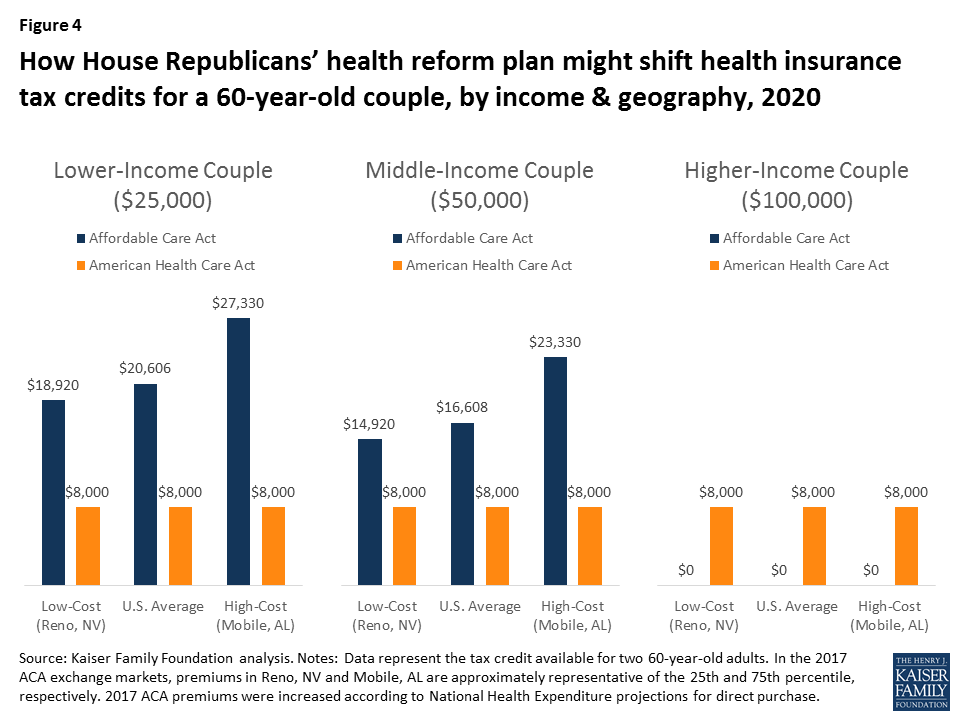

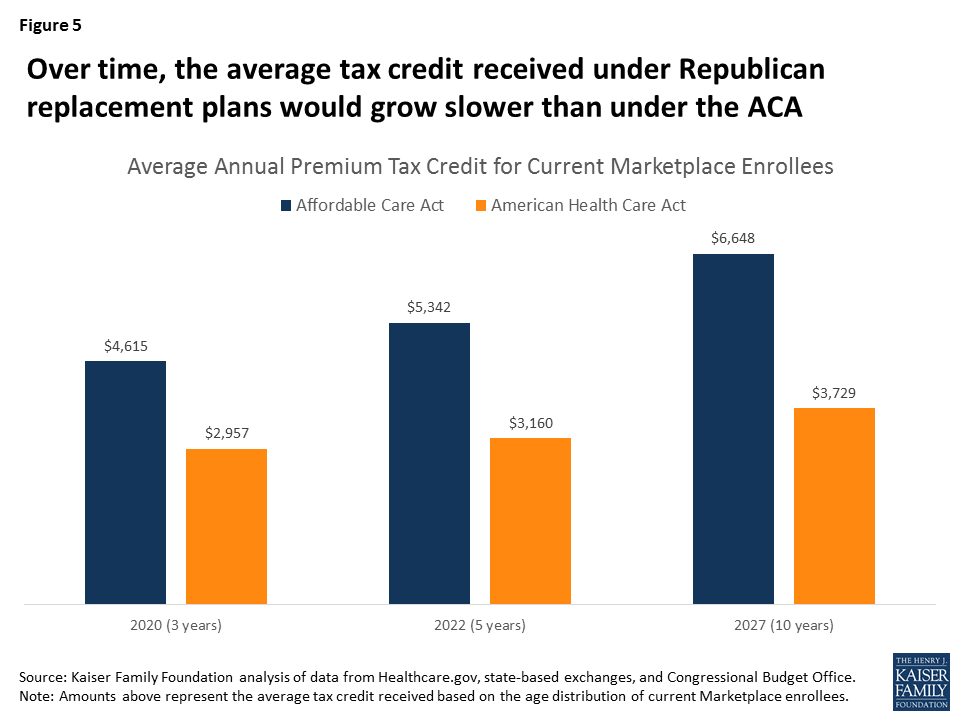

The ACA and leading replacement proposals rely on refundable tax credits to help individual market enrollees pay for premiums, although the credit amounts are set quite differently. The House Leadership proposal released on March 6, the American Health Care Act, proposes refundable tax credits which vary with age (with a phase-out for high-income enrollees) and grow annually with inflation. The tax credits under the ACA vary with family income and the cost of insurance where people live, as well as age, and grow annually if premiums increase.

These various tax credit approaches can have quite different implications for different groups of individual market purchasers. For example, the tax credits under the ACA are higher for people with lower incomes than for people with higher incomes, and no credit is provided for individuals with incomes over 400% of poverty. The current replacement proposal, in contrast, is flat for incomes up to $75,000 for an individual and $150,000 for a married couple, and so would provide relatively more assistance to people with upper-middle incomes. Similarly, the ACA tax credits are relatively higher in areas with higher premiums (like many rural areas), while the replacement proposal credits do not vary by location. If premiums grow more rapidly than inflation over time (which they generally have), the replacement proposal tax credits will grow more slowly than those provided under the ACA.

What is a Tax Credit, and How is it Different from a Deduction?

A tax credit is an amount by which a taxpayer can reduce the amount they owe in federal income tax; for example, if a person had a federal tax bill of $2,500 and a tax credit of $1,000, their tax liability would be reduced to $1,500. A refundable tax credit means that if the amount of the tax credit is greater than the amount of taxes owed, the taxpayer receives a refund of the difference; for example, if a person had a federal tax bill of $1000 and a tax credit of $1,500, they would receive a refund of $500. Making the credit refundable is important if a goal is to assist lower-income families, many of whom may not owe federal income tax. An advanceable tax credit is made available at the time a premium payment is owed (which similarly benefits lower-income families so that they can receive the financial assistance upfront). The ACA and a number of replacement proposals allow for advance payment of credits.

A tax credit is different from a tax deduction. A deduction reduces the amount of income that is taxed, while a credit reduces the amount of tax itself. For example, if a person has taxable income of $30,000, a $500 deduction reduces the amount of taxable income to $29,500. If the person’s marginal tax rate is 15%, the deduction reduces the person’s taxes by 15% of $500, or $75. Because people with lower incomes have lower marginal tax rates than people with higher incomes – and, typically don’t itemize their deductions – tax credits are generally more beneficial to lower income people than deductions.

The next section describes the differing tax credit approaches in more detail and draws out some of the implications for different types of purchasers.

The ACA provides tax credits for individuals with family incomes from 100% to 400% of poverty ($11,880 to $47,520 for a single individual in 2017) if they are not eligible for employer-provided or public coverage and if they purchase individual market coverage in the federal or a state marketplace. The tax credit amounts are calculated based on the family income of eligible individuals and the cost of coverage in the area where the live. More specifically, the ACA tax credit for an eligible individual is the difference between a specified percentage of his or her income (Table 1) and the premium of the second-lowest-cost silver plan (referred to as the benchmark premium) available in the area in which they live. There is no tax credit available if the benchmark premium is less than the specified percentage of income (which can occur for younger purchasers with relatively higher incomes) or if family income falls outside of the 100% to 400% of poverty range. For families, the premiums for family members are added together (including up to 3 children) and compared to specified income percentages. ACA tax credits are made available in advance, based on income information provided to the marketplace, and reconciled based on actual income when a person files income taxes the following.

| Table 1: Affordable Care Act Tax Credit Premium Cap, by Income in 2017 | |

| Income % Poverty | Premium Cap (maximum % of income one must pay for second-lowest silver plan available to in their area) |

| Under 100% | No Cap |

| 100% – 133% | 2.04% |

| 133% – 150% | 3.06% – 4.08% |

| 150% – 200% | 4.08% – 6.43% |

| 200% – 250% | 6.43% – 8.21% |

| 250% – 300% | 8.21% – 9.69% |

| 300% – 400% | 9.69% |

| Over 400% | No Cap |

| Source: Kaiser Family Foundation | |

Take, for example, a person age 40 with income of $30,000, which is 253% of poverty. At this income, the person’s specified percentage of income is 8.28% in 2017, which means that the person receives a tax credit if he or she has to pay more than 8.28% of income (or $2,485 annually) for the second-lowest-cost silver premium where he or she lives. If we assume a premium of $4,328 (the national average benchmark premium for a person age 40 in 2017), the person’s tax credit would be the difference between the benchmark premium and the specified percentage of income, or $4,328 – $2,485 = $1,843 (or $154 per month).

The American Health Care Act takes a simpler approach and specifies the actual dollar amounts for a new refundable tax credit that could be used to purchase individual market coverage. The amounts vary only with age up until an income of $75,000 for a single individual, at which point they begin to phase out. Tax credits range from $2,000 for people under age 30, to $2,500 for people ages 30 to 39, $3,000 for people age 40 to 49, $3,500 for people age 50 to 59, and $4,000 for people age 60 and over starting in 2020. Eligibility for the tax credit phases out starting at income above $75,000 for single individuals (the credit is reduced, but not below zero, by 10 cents for every dollar of income above this threshold, reaching zero at an income of $95,000 for single individuals up to age 29 or $115,000 for individuals age 60 and older). For joint filers, credits begin to phase out at an income of $150,000 (the tax credit is reduced to zero at an income of $190,000 for couples up to age 29; it is reduced to zero at income $230,000 for couples age 60 or older; and it is reduced to zero at income of $290,000 for couples claiming the maximum family credit amount). People who sign up for public programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, public employee health benefit programs, would not be eligible for a tax credit. The proposal further limits eligibility for tax credits to people who do not have an offer available for employer-provided health benefits.

Table 2 shows how projected ACA tax credits in 2020 compare to what would be provided under the American Health Care Act for people at various incomes, ages, and geographic areas. To show the ACA amounts in 2020, we inflated all 2017 premiums based on projections for direct purchase spending per enrollee from the National Health Expenditure Accounts. This method applies the same premium growth across all ages and geographic locations. Note that the table does not include cost-sharing assistance under the ACA that lowers deductibles and copayments for low-income marketplace enrollees. For example, in 2016, people making between 100 – 150% of poverty enrolled in a silver plan on healthcare.gov received cost-sharing assistance worth $1,440; those with incomes between 150 – 200% of poverty received $1,068 on average; and those with incomes between 200 – 250% of poverty received $144 on average.

| Table 2: Projected Annual Premium Tax Credit available in the Individual Market under the Affordable Care Act and the American Health Care Act, 2020 | |||||||

| Income (2020 FPL) | Age | Affordable Care Act | American Health Care Act | ||||

| Reno, NV | US Average | Mobile, AL | Reno, NV | US Average | Mobile, AL | ||

| $20,000 (160% FPL) | 27 | $2,899 | $3,225 | $4,522 | $2,000 | $2,000 | $2,000 |

| 40 | $3,745 | $4,143 | $5,725 | $3,000 | $3,000 | $3,000 | |

| 60 | $9,030 | $9,874 | $13,235 | $4,000 | $4,000 | $4,000 | |

| $40,000 (320% FPL) | 27 | $0 | $103 | $1,400 | $2,000 | $2,000 | $2,000 |

| 40 | $623 | $1,021 | $2,603 | $3,000 | $3,000 | $3,000 | |

| 60 | $5,908 | $6,752 | $10,113 | $4,000 | $4,000 | $4,000 | |

| $75,000 (600% FPL) | 27 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $2,000 | $2,000 | $2,000 |

| 40 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $3,000 | $3,000 | $3,000 | |

| 60 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $4,000 | $4,000 | $4,000 | |

| $100,000 (800% FPL) | 27 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 40 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $500 | $500 | $500 | |

| 60 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $1,500 | $1,500 | $1,500 | |

| Source: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis. Notes: In the 2017 ACA exchange markets, premiums in Reno, NV and Mobile, AL are approximately representative of the 25th and 75th percentile, respectively. 2017 ACA premiums were increased according to National Health Expenditure projections for direct purchase. Under the ACA, people with incomes below 250% of the poverty level receive additional financial assistance for cost-sharing (not shown above). | |||||||

Under the ACA in 2020, we project that a typical 40-year-old making $20,000 per year would be eligible for $4,143 in premium tax credits (not including the additional cost-sharing subsidies to lower his or her deductibles and copayments), while under the American Health Care Act, this person would be eligible $3,000. For context, we project that the average ACA premium for a 40-year-old in 2020 would be $5,101 annually (meaning the tax credit in the ACA would cover 81% of the total premium) for a benchmark silver plan with comprehensive benefits and reduced cost-sharing. A $3,000 tax credit for this same individual under the American Health Care Act would represent 59% of the average 40-year-old benchmark silver premium under the ACA.

Generally, the ACA has higher tax credit amounts than the replacement plan for lower-income people – especially for those who are older and live in higher-cost areas – and lower credits for those with higher incomes. Unlike the ACA, the replacement plan provides tax credits to people over 400% percent of the poverty level (phasing out around 900% of poverty for a single person), as well as to people current buying individual market coverage outside of the marketplaces (not included in this analysis).

While replacement plan tax credits vary by age – by a factor of 2 to 1 for older adults relative to younger ones – the variation is substantially less than under the ACA. The big differences in ACA tax credits at different ages is due to the fact that premiums for older adults can be three times the level of premiums for younger adults under the ACA, but all people at a given income level are expected to pay the same percentage of their income towards a benchmark plan. The tax credit fills in the difference, and this amount is much higher for older adults. These differences by age would be even further magnified under the American Health Care Act (which permits premiums to vary by a factor of 5 to 1 due to age). Before the ACA, premiums for older adults were typically four or five times the premiums charged to younger adults.

The tax credits in the ACA vary significantly with premium costs in an area (see Table 2 and Figure 2). At a given income level and age, people receive bigger tax credits in a higher premium area like Mobile, Alabama and smaller tax credits in a lower premium area like Reno, Nevada. Under the ACA in 2017, premiums in Mobile, Alabama and Reno, Nevada approximately represent the 75th and 25th percentile, respectively.

The disparities between the ACA tax credits and those in the American Health Care Act will therefore vary noticeably across the country. For more on geographic differences between the ACA and the replacement plan, see Tax Credits under the Affordable Care Act vs. the American Health Care Act: An Interactive Map.