Data Note: Three Findings about Access to Care and Health Outcomes in Medicaid

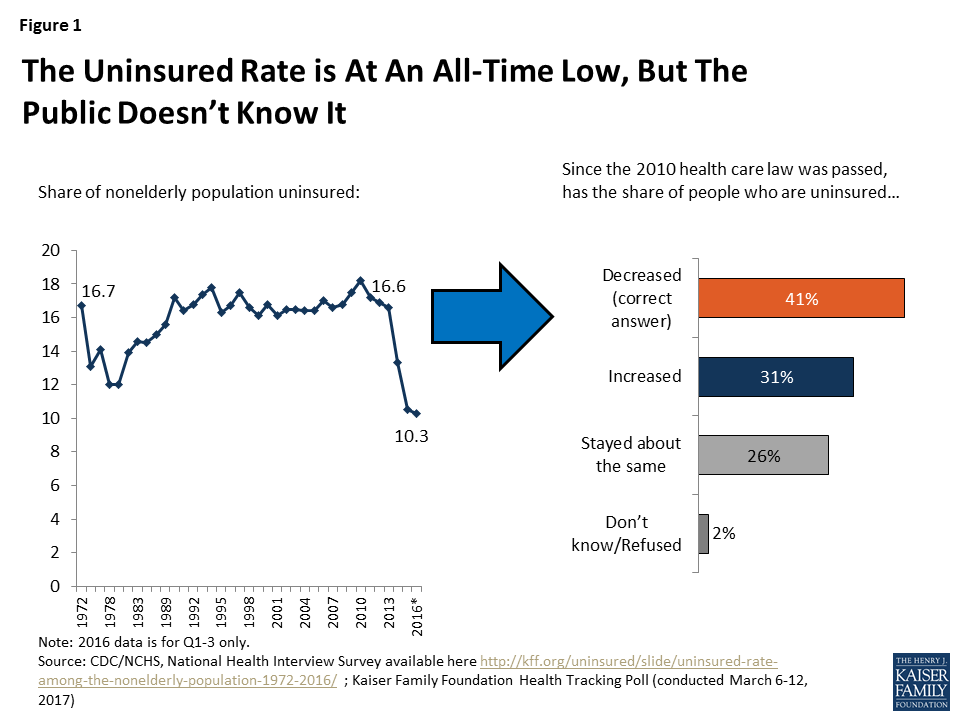

The Medicaid program provides health coverage for 74 million low-income Americans, including many of the poorest and sickest people in our society. Among those served by Medicaid are pregnant women, infants, and children, parents and other adults, poor seniors, and people of all ages with physical, cognitive, and other disabilities. Given Medicaid’s major coverage role and the complex health care needs of the population it covers, data and evidence on access to care and health outcomes in Medicaid are of key interest. Such an assessment is also important to ensure that debate about the effectiveness of the Medicaid program is grounded in facts and analysis. This Data Note examines the research on access and health outcomes in Medicaid.

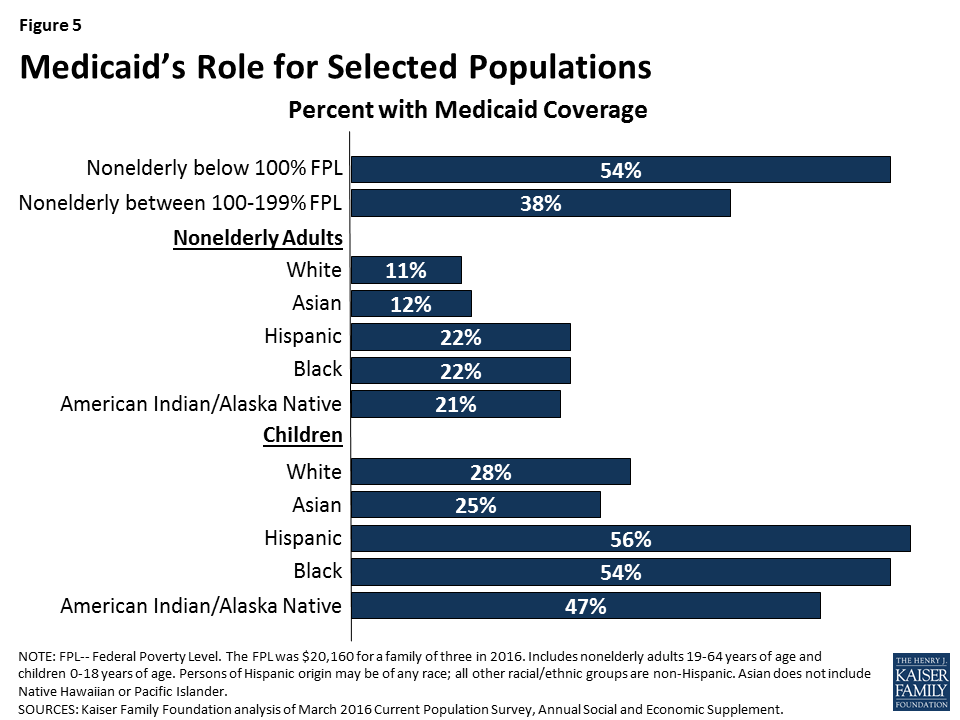

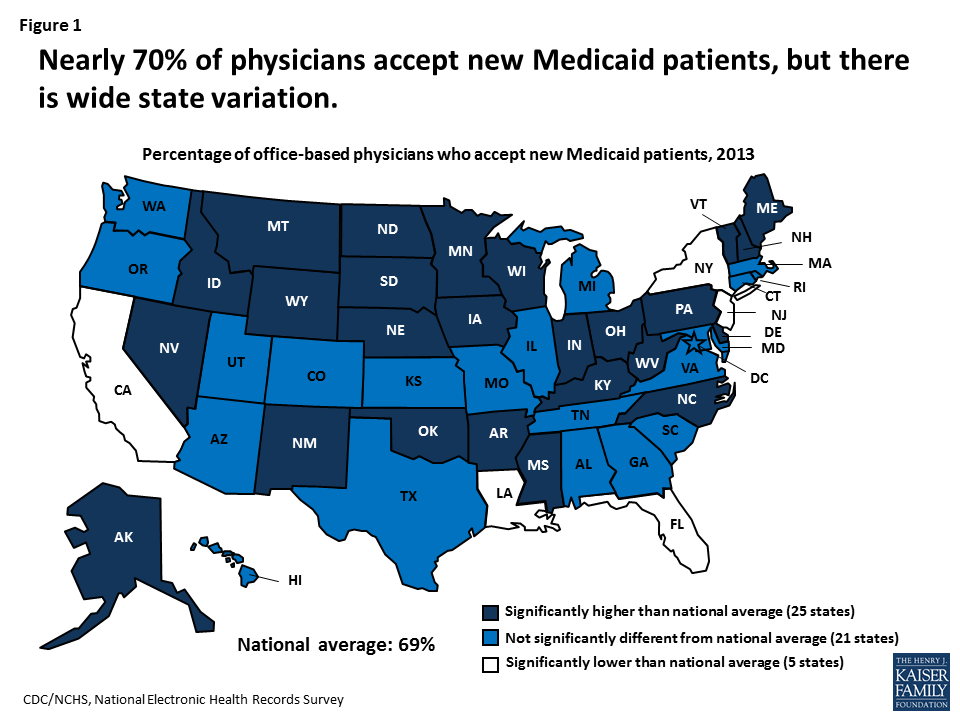

1. Most doctors accept new Medicaid patients.

About 70% of office-based physicians accept new Medicaid patients, compared to about 85% who accept new patients with private insurance or Medicare. The percentage of physicians accepting new Medicaid patients varies by state, ranging from 39% in New Jersey to 97% in Nebraska; the percentage accepting new privately insured patients ranges from 67% in the District of Columbia to 95% in Illinois. In 25 states, the percentage of physicians accepting new Medicaid patients is significantly higher than the national average, while in five states it is significantly lower (Figure 1). In 14 states, more than 85% of physicians accept new Medicaid patients, including 10 states where at least 90% do, and eight states where the percentage accepting new Medicaid patients is equal to or greater than the percentage accepting new privately insured patients.

In general, specialists are more likely than primary care physicians, except for pediatricians, to accept new Medicaid patients. But psychiatrists, in particular, are less likely to participate in Medicaid (and in health insurance generally) than other physicians. Virtually all doctors who practice in community health centers, which are a key source of primary care in low-income communities, accept new Medicaid patients. Well over half of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in contracted managed care plans, which are responsible for ensuring adequate provider networks and access to care for their Medicaid members.

There is no evidence that physician participation in Medicaid is declining. In a 2015 survey, 4 in 10 primary care physicians who accepted Medicaid reported seeing an increased number of Medicaid patients since January 2014, when the coverage expansions in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) took full effect. Research has shown a correlation between higher Medicaid fees and higher rates of physician participation in Medicaid. A recent 10-state “secret shopper” study found that the availability of new-patient primary care appointments for Medicaid patients increased significantly after Medicaid fees for primary care physicians were increased to Medicare levels under the ACA.

2. On key measures, access to care in Medicaid is comparable to private insurance, while the uninsured lag far behind.

Medicaid beneficiaries access health care at rates comparable to the rates for privately insured people and at sharply higher rates than the uninsured. In addition, Medicaid increases economic security for low-income households by making health care affordable, reducing financial strain, and protecting against catastrophic medical cost burdens and medical debt.

Ninety-five percent (95%) of children covered by Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) have a usual source of care, compared to 97% of children with private insurance and 69% of uninsured children. Nearly 90% of non-elderly adults with Medicaid as well as adults with private insurance have a usual source of care, while less than half of uninsured adults do; among adults at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), the privately insured are twice as likely as those with Medicaid to lack a usual source of care (19% versus 10%). Uninsured people are markedly less likely than Medicaid beneficiaries to get care and significantly more likely to delay or go without needed care due to cost.

Children covered by Medicaid are as likely as children with private coverage to receive a well-child checkup. They are also similarly likely to have had a primary care visit in the past year and, when health, demographic, and socioeconomic differences between the two groups are adjusted, they are just as likely to have had a specialist visit in the past year. Medicaid covers many children with special needs and disabilities, and provides wrap-around benefits for many children with special needs who have private insurance, giving them access to long-term therapies, medical equipment and supplies, and other supports and services not typically covered by private insurance. Under 4% of children with Medicaid/CHIP have trouble finding a doctor who accepts their insurance, compared to about 2% of children with private insurance.

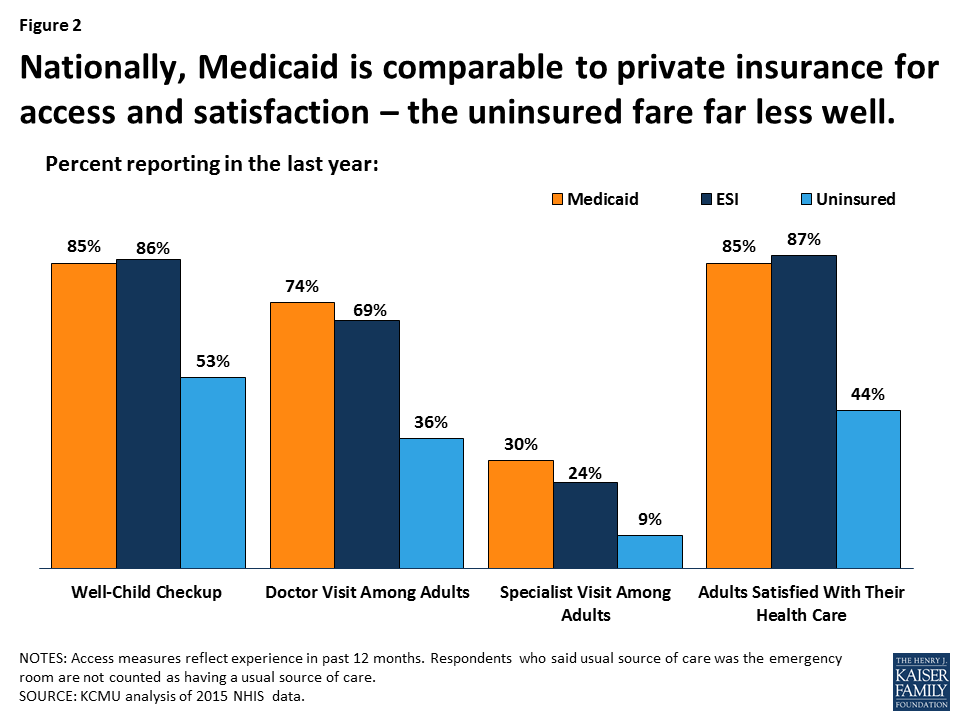

The data on adults tell a similar story. Adults with Medicaid are as likely as privately insured adults to have a doctor visit, receive specialist care, and report that they are satisfied with their health care (Figure 2). Among low-income adults (income at or below 250% FPL) with full-year coverage, those with Medicaid receive preventive care and cancer screening at similar rates to those with private health insurance. A large body of research shows that state Medicaid expansions to adults are associated with increased use of screening services and preventive care, diabetes medications and other prescription drugs, dental care, and other services. Medicaid adults are more likely than privately insured adults to have difficulty finding a provider with availability (11% versus 6%), but most of those who report difficulty do find a provider – under 3% of Medicaid adults (and 2% of privately insured adults) report that they were unable to find a doctor or provider with availability. Many studies show that providers have expanded their capacity and are meeting increased demand for care associated with the Medicaid expansion to adults.

Gaps in access to certain providers, particularly psychiatrists and dentists, are ongoing challenges in Medicaid. These and other gaps in access tend to mirror system-wide access problems that also affect Medicare and the private insurance market, but they are exacerbated in Medicaid by provider shortages in low-income communities, lower physician fees and participation in Medicaid compared to private insurance, and lack of transportation.

3. Evidence about Medicaid’s impact on health outcomes continues to emerge.

Like private health insurance and Medicare, Medicaid connects enrollees with health care providers and services. Access to screening and preventive care in Medicaid translates into well-child care and earlier detection of health and developmental problems in children, earlier diagnosis of cancer, diabetes, and other chronic conditions in adults, and earlier detection of mental illness in people of all ages. Access to physician care, prescription drugs, emergency care, and other services improves the likelihood that Medicaid enrollees will get treatment for both their acute and chronic conditions.

Multiple studies, though not all, have documented improvements in beneficiaries’ self-reported health, reduced stress and anxiety, and improved quality of life following Medicaid expansions. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, which used a research design that is considered the gold standard, compared the experience of adults who gained and adults who did not gain Medicaid coverage through a lottery that allocated a limited number of new Medicaid “slots” for low-income uninsured adults in the state. The study found that Medicaid improved self-reported mental health and reduced clinically observed rates of depression by 30% relative to the uninsured group. The findings related to impacts on physical health were mixed. Medicaid increased the detection of diabetes and use of diabetes medication, but did not have a statistically significant effect on control of diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol. The researchers note that the study did not have sufficient statistical power to detect changes in these measures, and also that factors including missed diagnosis and inappropriate or ineffective treatments, among others, could mitigate the impact of coverage on clinical outcomes.

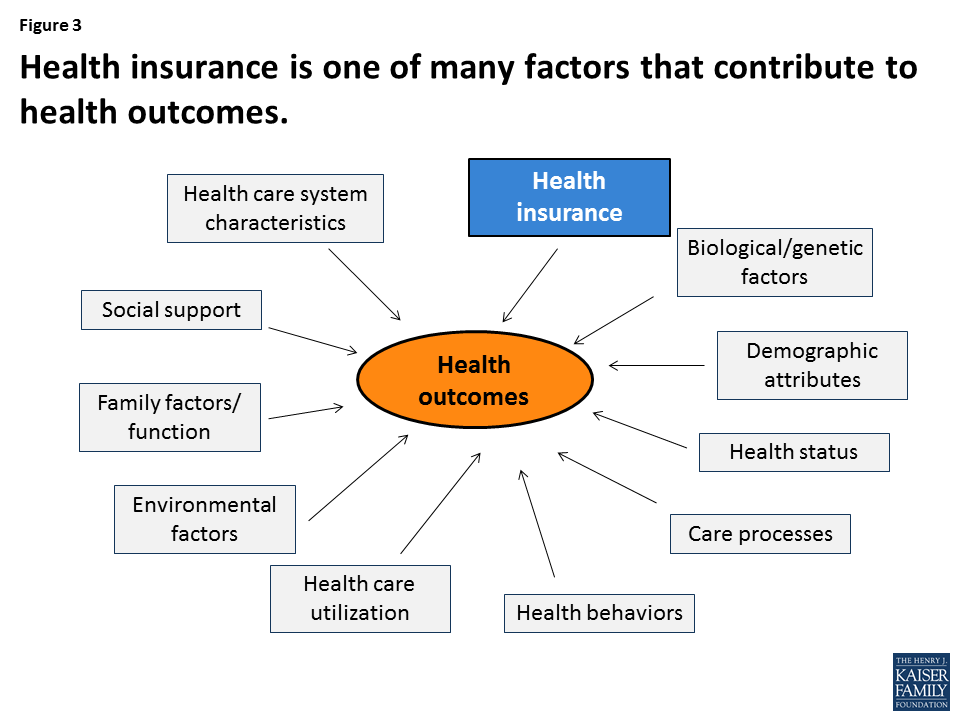

The purpose of health insurance is to increase access to care and provide protection against high out-of-pocket costs. Health outcomes are determined by a large number of variables, from genetic factors to social supports and environmental processes (Figure 3), and direct evidence that Medicaid or any other type of health coverage improves not just access to care, but also health outcomes, is limited. However, research documents that Medicaid coverage of pregnant women and children has contributed to dramatic declines in infant and child mortality in the United States. A growing number of studies show that Medicaid eligibility during childhood also has long-term positive impacts, including reduced teen mortality, reduced disability, improved long-run educational attainment, and lower rates of emergency department visits and hospitalization in later life. In addition, Medicaid eligibility during childhood appears to yield downstream benefits to the economy, in the form of reduced earned income tax credit payments and increased tax collections due to higher earnings in adulthood.

Conclusion

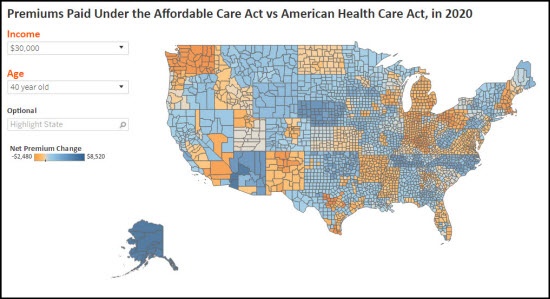

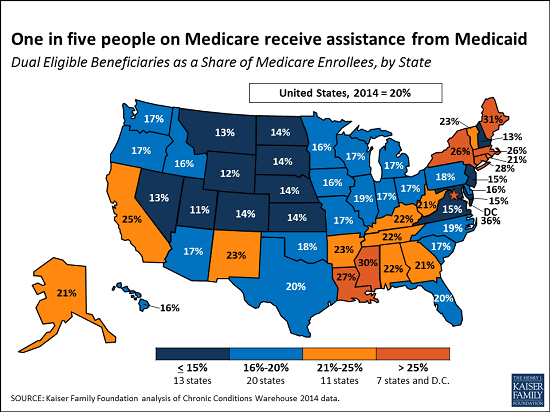

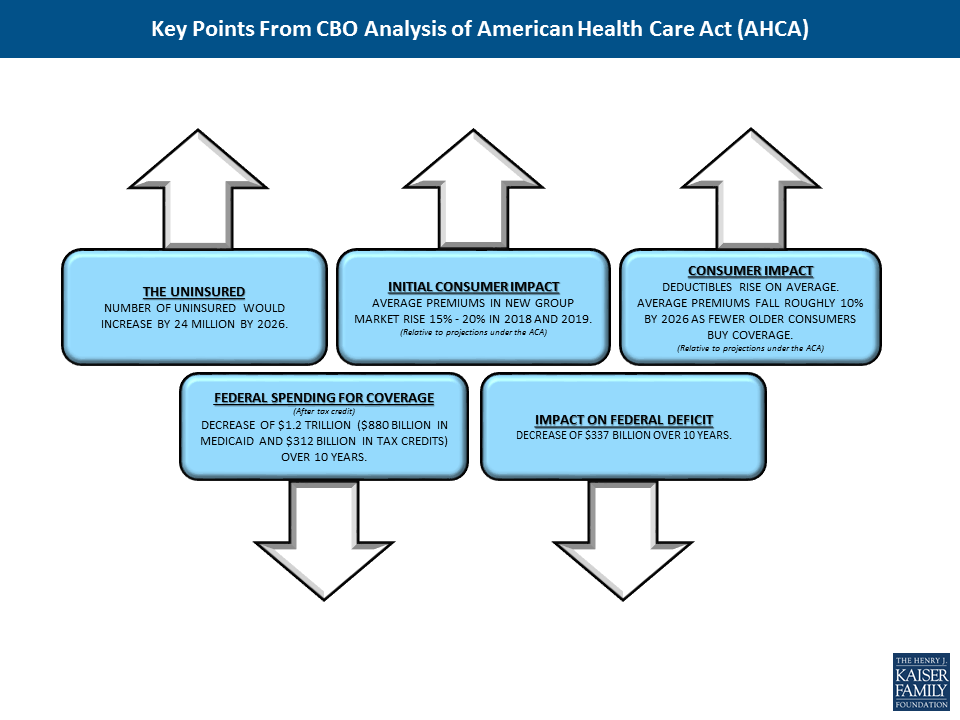

Medicaid covers 1 in 5 Americans today. Data and research provide evidence that Medicaid provides effective access to care for those it covers, including many of the poorest and sickest people in our nation. Because of the program, millions of otherwise uninsured low-income individuals and families – many of them with chronic conditions and disabilities – are able to see a doctor and gain entry into the health care system. The American Health Care Act, the Republican leadership’s plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, would cap federal funding for Medicaid for the first time in the program’s history, putting Medicaid coverage at risk for millions of low-income people. While the Medicaid program could be strengthened and improved, limiting the scope of Medicaid is likely to jeopardize access to care for the population most in need, with adverse consequences for their health and well-being in the near term and beyond.