Financing Family Planning Services for Low-income Women: The Role of Public Programs

Issue Brief

For more than 50 years, a network of public programs and providers have assisted millions of low-income women of childbearing age in the U.S. to obtain sexual and reproductive health services. Medicaid, the Title X Family Planning Program, and Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) provide critical support to more than 10,000 safety-net clinics across the country that provide reproductive health services to low-income women, men, and teens. Since the 2016 election, state and federal efforts to restrict public funding to Planned Parenthood and other abortion providers and to funnel new federal funds to faith-based providers who oppose contraceptives and abortion have gained traction and begun to shift the family planning landscape across the nation.

One in three low-income women in the US relies on a clinic, either a health center, Planned Parenthood or other publicly-funded clinic to get contraception (Figure 1). These providers also offer STI screening and treatment services, and other preventive care and for some women are the sole source of their medical care. Medicaid, Title X, and other federal and government programs are critical sources of funding for these clinic-based providers. Poor women are more likely to experience an unintended pregnancy, have an abortion, contract a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and have less access to care than higher income women. In 2017, approximately 30% (21 million) of reproductive-age women lived in households that earned less than 200% of the federal poverty level ($40,840 for a family of three).

Major Public Programs for Financing Family Planning Services for Low-Income People

Medicaid –Health coverage program that covers more than 70 million low-income individuals. Operated jointly by federal and state governments, all beneficiaries have coverage for family planning services, and according to federal statute, may see the participating provider of their choice. Medicaid is the largest funding source for public family planning services.

Title X – The nation’s only federal program specifically dedicated to supporting the delivery of family planning care. The program provides funds to approximately 4,000 clinics across the nation to support the delivery of family planning services to low-income individuals.

Section 330 Grants – Provides core support to the nation’s Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), the largest system of clinics providing primary care services to poor and underserved patients. All FQHCs provide some family planning care within their network.

Over the past three years, policy changes at the state and federal level in Medicaid and Title X have restricted providers from receiving federal and state funds if they provide abortion services in addition to family planning care. This brief reviews the role of these public programs and providers in financing care and enabling access to family planning services. It also addresses the impact of actions taken by President Trump and Congress to block federal funds from Planned Parenthood and other entities that provide abortion.

Medicaid is the Primary Source of Public Funding for Family Planning

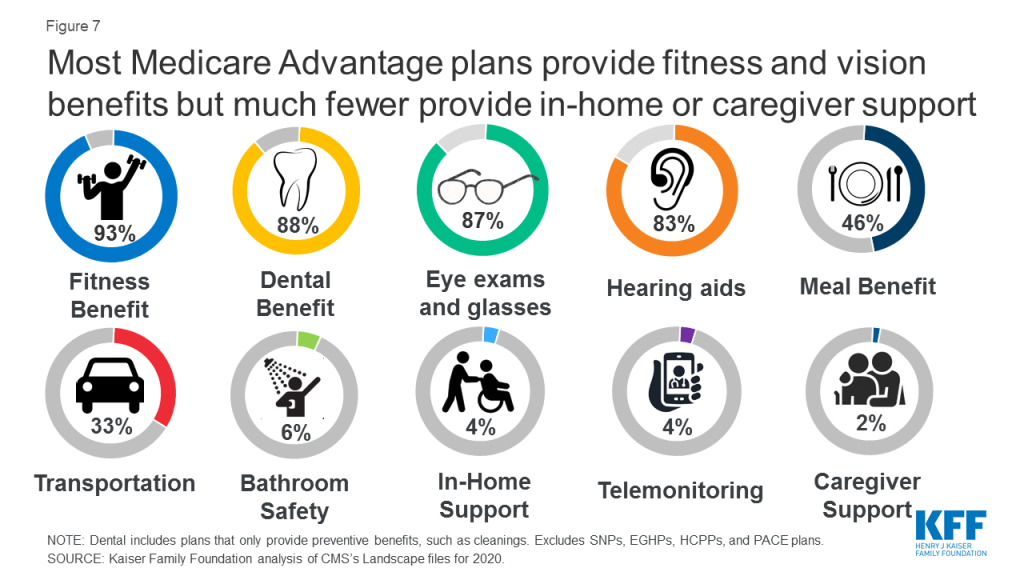

Medicaid, a jointly operated and funded federal/state program, covers more than four in ten (44%) low-income women of reproductive age, the leading source of coverage among this population (Figure 2). Across the nation, the share of low-income reproductive-age women enrolled in Medicaid varies considerably by state. These differences are the result of state choices about Medicaid eligibility, particularly whether the state has expanded Medicaid to all adults up to 138% FPL as permitted by the ACA and state-established income eligibility thresholds for parents in the non-expansion states. Coverage rates range from a high of 71% of reproductive age women in Vermont to a low of 22% in Utah (Appendix Table 1). In 2014, the most recent year in which national enrollment data is available, 19.1 million reproductive-age women were enrolled in the program. For these women, Medicaid provides comprehensive affordable coverage to help meet the full range of their health care needs, and guarantees that they will not have any out of pocket costs for family planning services and pregnancy-related care.

Medicaid accounted for 75% of all public funds spent on contraceptive services and supplies in 2015. Federal law stipulates that family planning is a “mandatory” benefit that states must cover under Medicaid, but provides states, with considerable discretion in specifying the services and supplies that are included in the program. Most state Medicaid programs make the full range of FDA approved contraceptives available to women, and nearly all cover counseling on STIs and HIV as well as screening for cervical cancer.

Other federal requirements that shape family planning policy under Medicaid include:

- The federal government pays 90% of all family planning services and supplies, and states pay 10%. This is considerably higher than the federal match that states receive for most other services, which ranges from 50% to 78%, depending on the state.

- Federal law prohibits cost sharing for any family planning (and pregnancy-related) services.

- States must allow “any willing provider” to participate in the Medicaid program unless there is “evidence of fraud or criminal action, material non-compliance with relevant requirements, or material issues concerning the fitness of the provider to perform covered services or appropriately bill for them.” While this provision is not specific to family planning, the policy means that states cannot bar providers from the program simply because they provide abortion services.

- Medicaid beneficiaries have “freedom of choice” to obtain family planning services from any provider participating in the program. For those enrolled in managed care plans, there is an additional protection, ensuring that beneficiaries may seek family planning services even if the provider is outside of the plan’s network.

- The Hyde Amendment prohibits any federal dollars, including Medicaid reimbursements, from being used to pay for abortions except in cases of rape, incest or life endangerment of the woman. Clinics, including some Planned Parenthood sites, which provide both family planning and abortion services, cannot be reimbursed with federal Medicaid dollars for abortions, but they can be paid for all services including contraceptives, cancer screenings, and STI testing and treatment.

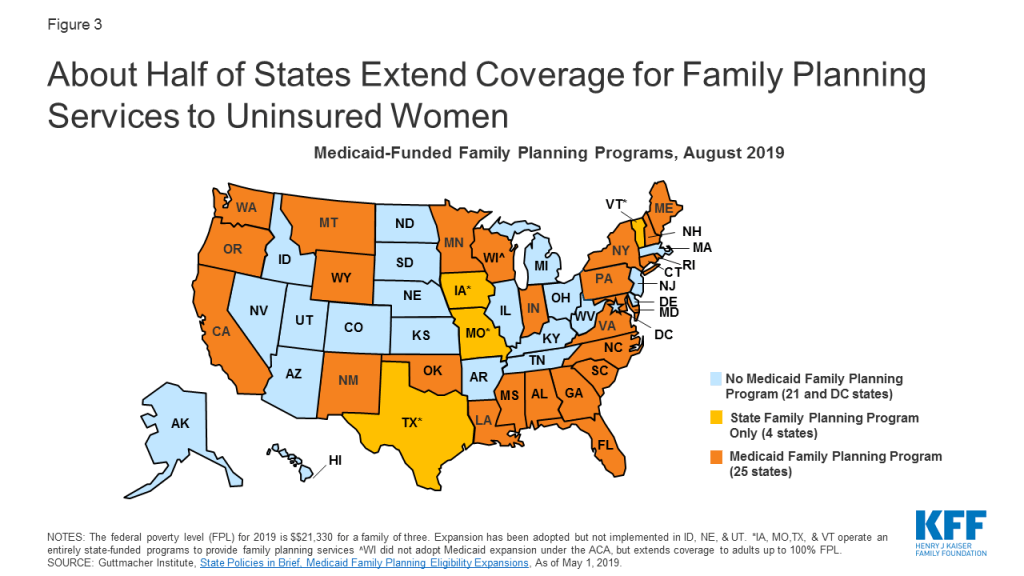

- States may establish limited scope programs through Medicaid Section 1115 Research and Demonstration Waivers or through State Plan Amendments (SPAs) to provide family planning services to individuals who do not qualify for full-scope Medicaid. Today, more than half of states have established such programs (Figure 3).

Title X Funds Support Clinics That Provide Family Planning Services to Low-Income People

The Title X National Family Planning Program, a federal block grant administered by the HHS Office of Population Affairs (OPA), is the only federal program specifically dedicated to supporting the delivery of family planning care. The program funds organizations in each state to distribute federal dollars to safety-net clinics to provide family planning services to low-income, uninsured, and underserved clients. In June of 2019, approximately 4,000 clinics nationwide received Title X funding, including specialized family planning clinics such as Planned Parenthood centers, primary care providers such as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), and health departments, school-based, faith-based, and other private nonprofits (Appendix Table 2). In 2018, two-thirds (65%) of clients seen at Title X clinics had family incomes at or below the poverty level, 38% were covered by Medicaid or another public program, and four in ten (40%) were uninsured.

Title X grantees must serve low-income populations at low or no cost, and have historically been required to provide clients with a broad range of contraceptive methods as recommended by the national Quality Family Planning Guidelines (QFP), and ensure that the services are voluntary and confidential. In addition to providing clinics with funds to cover the direct costs of family planning services and supplies such as contraceptives, Title X funds enable clinics to pay for patient and community education services about family planning and sexual health issues, as well as infrastructure expenses such as rent, utilities, information technology, and staff salaries. Title X clinics are also eligible to obtain discounted prescription contraceptives and devices through the federal 340B program. No other federal program makes funds available to support clinic infrastructure needs specifically for family planning. In contrast, Medicaid reimburses for specific clinical services.

Signed into law by President Nixon in 1970, the Title X program is currently funded at $285 million. The program budget, however, has not kept pace with medical price inflation over time. Clinics that provide family planning services have a mix of revenue sources, including grant funds from Title X and other programs, reimbursement for patients covered by Medicaid or private insurance, and some out of pocket payments from patients. Title X clinics received 19% of their revenue from the Title X grant, while Medicaid reimbursement accounted for 39% of revenue in 2018.

Over the past decade, the Title X program has experienced significant financial cutbacks due to federal budget reductions and freezes. In addition, some Congressional leaders have questioned the need to continue to fund the program, the types of services that the program can cover and the providers who qualify for funding. In March 2019, the Trump administration published a new regulation that alters the program significantly. In particular, the new rules block the availability of federal funds to family planning providers, such as Planned Parenthood, if they also offer abortion services with non-Title X funds. The regulation also prohibits Title X-funded providers from making referrals to abortion services for pregnant women seeking that care and requires providers that receive Title X support to refer all pregnant women to prenatal care even if a woman wants to terminate the pregnancy.

Currently, the new regulation is in effect, but it has been challenged by 23 states, major family planning organizations, and the American Medical Association in federal court, claiming the new rules violate the Constitution and federal law. As of October 2019, 18 of 90 grantees that had received funding in April 2019 are no longer participating in the program because they are unwilling to comply with the new federal regulations that limit their ability to provide clients with abortion referrals and block them from participating if they also offer abortion services. In addition, one quarter of the family planning (approximately 1,000 clinics) network no longer receive Title X funding to support family planning services to low-income women in the community and some states are no longer participating in the Title X program. The loss of Title X funding may force some clinics to close and others to reduce hours, services, and staff training.

Many Health Centers Offer Family Planning Services, but the Range and Volume of Services They Provide Varies

Under Section 330 of the PHSA, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) provides grants to health centers whose main focus is providing primary and preventive care to underserved and vulnerable populations. These clinics, called Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), are required to provide “voluntary family planning” services along with a wide range of health care services. Although it is not specifically defined in FQHC guidelines, voluntary family planning services can include preconception care, screening and treatment of STIs, and contraception. A survey of FQHCs found that virtually all reported they provided at least one method of contraception at one or more of their clinical sites.

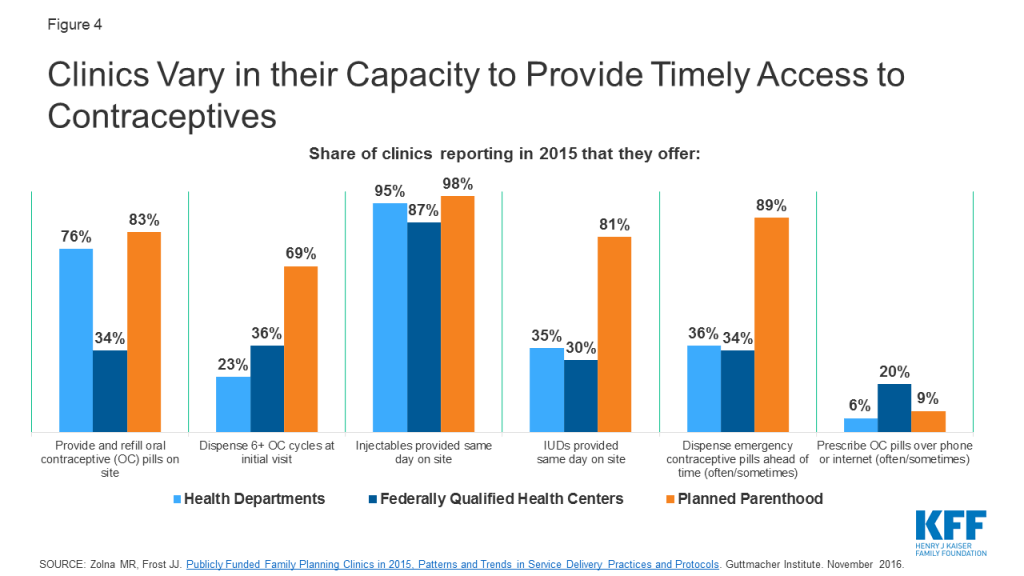

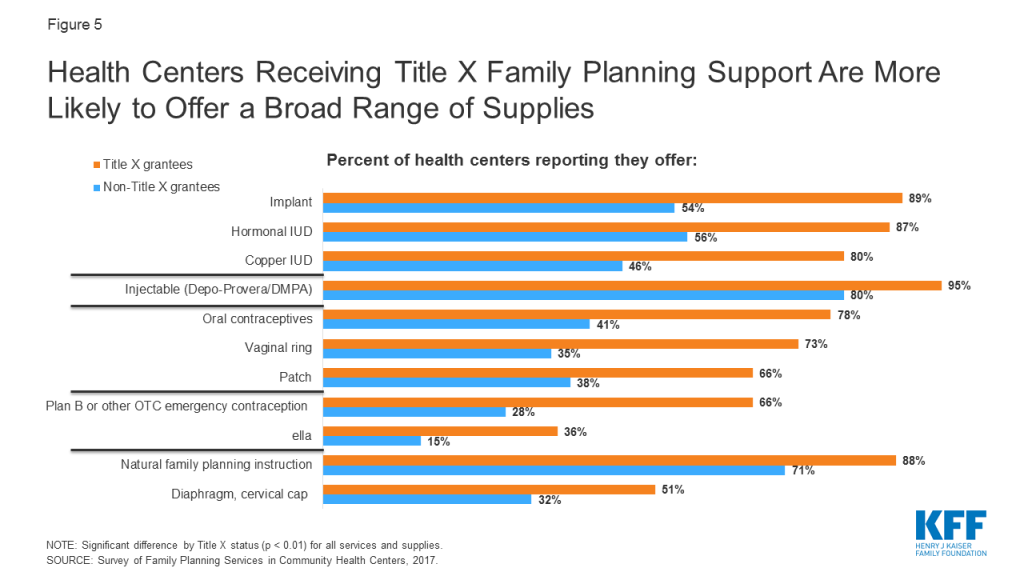

However, research has documented differences between clinic types in their ability to offer direct access to the most effective contraceptive methods (Figure 4). For example, about eight in ten Planned Parenthood clinics (83%) and three-quarters of health department clinics (76%) can provide initial supply and refills of oral contraceptives on site, compared to one-third (34%) of FQHCs. Similarly, there are differences in capacity for family planning care within the FQHC network. In a 2017 Kaiser Family Foundation/ George Washington University study of FQHCs, 80-90% of centers that received Title X funds reported they provide LARCs, compared to just about half of FQHCs that did not receive Title X support (Figure 5).

FQHCs are paid using the Prospective Payment System (PPS), which is a higher rate to ensure their costs are coverage and clinics are fully reimbursed for Medicaid patient services, allowing them to utilize their federal 330 grant to care for uninsured and under-insured patients. FQHCs must have a sliding fee scale for patients with incomes below 200% FPL and offer services to all patients regardless of their ability to pay. Of those served in 2017, 69% lived at or below the poverty line, 23% were uninsured, and 49% were covered by Medicaid or CHIP.Similar to Title X clinics, FQHC funding comes largely from Medicaid payments, which made up 44% of revenue in 2017, followed by Section 330 grants (18%) and state, local, and private grants (38%).

Recent Federal and State Efforts Have Moved to Disqualify Planned Parenthood Clinics from Receiving Title X Support and Reimbursements under Medicaid

In the first three years of the Trump Administration, the President and many Congressional Republicans pursued multiple avenues to restrict public funds from going to Planned Parenthood and other clinics that provide both contraception and abortion services. In 2017, the Administration reversed an Obama era regulation that would have prevented states from blocking Title X funds from going to Planned Parenthood and other clinics that provide abortion using other funds. In 2017, every version of Republican legislation to replace the ACA included provisions that would have banned federal Medicaid payments to Planned Parenthood clinics. While none of these bills were enacted, this would have upended Medicaid’s “free choice of provider” requirement and would have resulted in a significant revenue loss for Planned Parenthood.

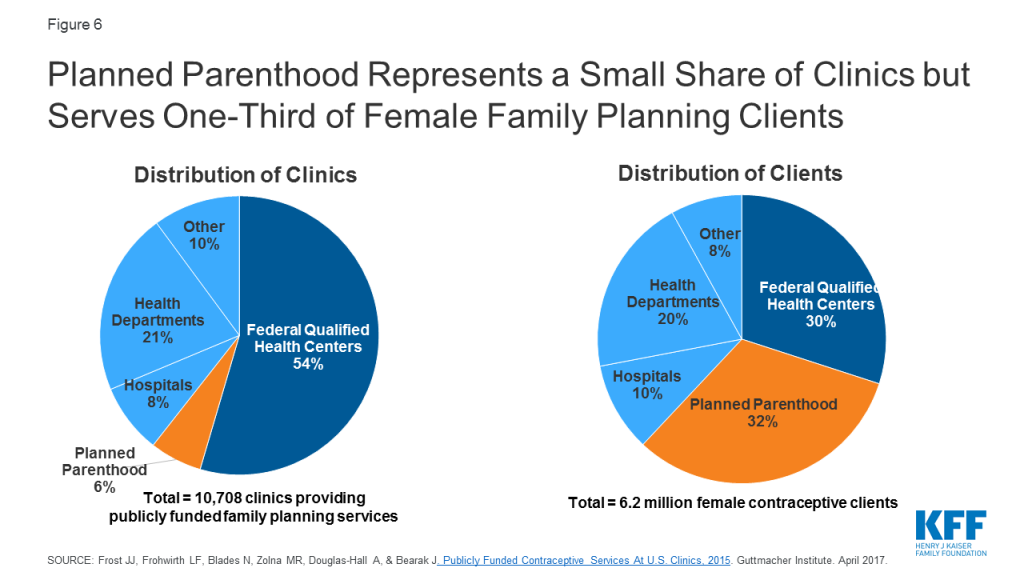

A common theme among proposals to block Planned Parenthood and other specialized family planning clinics from the Medicaid program is the redirection of funds to other providers, such as community health centers (CHCs), with the expectation that CHCs could meet the needs of those formerly served by Planned Parenthood. However, Planned Parenthood served approximately one-third (32%) of women seeking contraceptives at safety-net clinics in 2015. In contrast, while there are considerably more FQHCs (representing 54% of safety-net clinics), they served roughly the same share (30%) of women seeking contraceptive care as Planned Parenthood (Figure 6). CHCs and other remaining clinics would not likely be able to meet additional demands that would be placed on them to provide the full range of family planning services.

The impact of banning federal Title X funds and Medicaid reimbursement to family planning clinics would vary across the country. In some states there are very few Planned Parenthood clinics, while in other states they are the predominant provider for low-income people seeking contraceptive services. In 13 states, Planned Parenthood clinics were the site of care for over 40% of women who obtained publicly funded contraceptives.

Experience at the state level has shown that blocking Planned Parenthood from receiving Medicaid reimbursements or Title X funding reduces low-income women’s access to contraceptives. In 2013, Texas replaced its federally funded family planning waiver program with a 100% state funded program that excluded Planned Parenthood as a participating provider. Following the policy change, there was a sharp drop in the number of women served by the state’s program, and access problems have persisted. A recent study found that approximately one-third of publicly insured women in Texas reported difficulty finding a provider (36%) that accepts their coverage and locating a provider that offers services (33%). Furthermore, there was a sizable drop in Medicaid claims for IUDs, contraceptive implants, and injectable contraceptives (IUDs and implants are the most costly and effective methods) and an increase in Medicaid-funded births. In 2013, the Wisconsin legislature approved family planning cuts directed at Planned Parenthood, which resulted in the closure of five Planned Parenthood clinics in rural areas. Women who used the Planned Parenthood clinics were referred to other clinics that were usually further away with wait lists that did not provide the full range of contraceptive methods. A study conducted by Health Management Associates for Planned Parenthood concluded that women in seven Wisconsin counties would have no alternative family planning provider should Planned Parenthood centers close there.

Several other states have also attempted to limit public funds to clinics that provide contraception and abortion services, including Planned Parenthood. Three states – Texas, Tennessee, and South Carolina, have applied to CMS for a federal waiver to exclude abortion providers from their Medicaid networks for non-abortion services, while Arkansas and Missouri have already done so, despite the federal free choice of provider requirement. Several other states have blocked state and Title X funds to clinics that provide both family planning and abortion (Table 1). These restrictions were in place prior to the Trump Administration’s change to the Title X program, which affect the entire nation. Should the federal Title X rules get reversed in court, state-level limits would remain in place.

| Table 1: Selected State Policies and Legislative Proposals Regarding Public Funding for Family Planning Providers | |

| State Efforts to Limit or Protect Funding for Family Planning Providers | States |

| Bans certain family planning providers from receiving Medicaid funds | Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, Texas |

| Applied to federal government for waiver from Medicaid free choice of provider requirement | South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas |

| Prevents state family planning and/or Title X funds to providers that offer abortion services, regardless of federal policy | Mississippi, Nebraska, Wisconsin |

| Prohibits other forms of public funds^ to abortion providers or entities affiliated with abortion provision or referral | Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, North Carolina, Texas, Wisconsin |

| NOTE ^Public funds from programs such as Sex education, Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act, Violence Against Women Act, HIV/AIDS initiatives, etc. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of state legislation; Guttmacher Institute. State Family Planning Funding Restrictions. June 2019. | |

Looking Forward

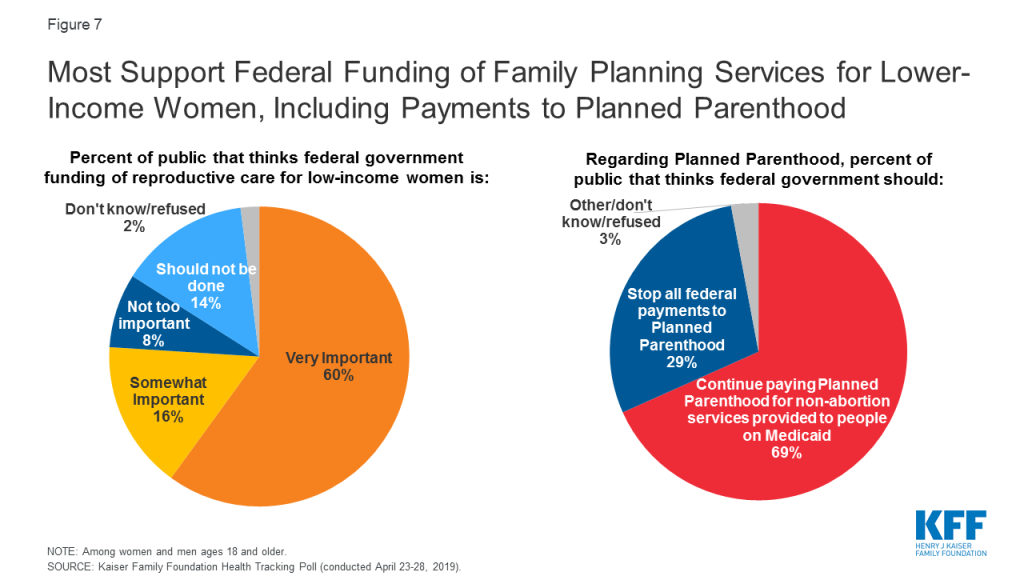

Federal and state funding that supports Medicaid, the Title X program, and Section 330 of the PHSA is the financial core for safety-net clinics that provide family planning services to the uninsured and other vulnerable populations. This federal funding of family planning services and Planned Parenthood receives considerable public support. Almost nine in ten (86%) people say it is important for the federal government to provide funding for reproductive health services, including family planning and birth control for lower-income women, and 69% say they support continued federal Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood for non-abortion services (Figure 7). The Trump Administration’s changes to health care policy under Title X as well as state actions to restrict funding to Planned Parenthood under Medicaid are still playing out, with the likelihood that they will create gaps in access for low-income individuals that rely on these programs for their family planning care.

Appendix

| Appendix Table 1: Coverage of Low-Income Women of Reproductive Age, by State, 2017 | |||||

| State | Estimated Number of Total Women Ages 15-49 | Low-Income Women Ages 15-49 | |||

Estimated Number of Low-Income Women (<200% FPL) | Share of Women Who are Low-Income | Share of Low-Income Women Covered by Medicaid | Share of Low-Income Women Who are Uninsured | ||

| United States | 72,811,000 | 21,257,000 | 29% | 44% | 20% |

| Alabama | 1,084,000 | 417,000 | 38% | 34% | 23% |

| Alaska | 165,000 | 38,000 | 23% | 51% | 18% |

| Arizona | 1,533,000 | 500,000 | 33% | 49% | 21% |

| Arkansas | 649,000 | 248,000 | 38% | 50% | 15% |

| California | 9,255,000 | 2,597,000 | 28% | 55% | 15% |

| Colorado | 1,298,000 | 300,000 | 23% | 47% | 17% |

| Connecticut | 770,000 | 159,000 | 21% | 58% | 11% |

| Delaware | 206,000 | 56,000 | 27% | 39% | 10% |

| DC | 190,000 | 44,000 | 23% | 64% | n/a |

| Florida | 4,434,000 | 1,441,000 | 32% | 32% | 28% |

| Georgia | 2,453,000 | 804,000 | 33% | 26% | 33% |

| Hawaii | 298,000 | 59,000 | 20% | 49% | 8% |

| Idaho | 372,000 | 123,000 | 33% | 27% | 25% |

| Illinois | 2,898,000 | 811,000 | 28% | 49% | 16% |

| Indiana | 1,469,000 | 445,000 | 30% | 42% | 18% |

| Iowa | 661,000 | 172,000 | 26% | 46% | 11% |

| Kansas | 625,000 | 189,000 | 30% | 27% | 23% |

| Kentucky | 963,000 | 336,000 | 35% | 58% | 10% |

| Louisiana | 1,060,000 | 431,000 | 41% | 52% | 14% |

| Maine | 267,000 | 66,000 | 25% | 50% | 17% |

| Maryland | 1,372,000 | 277,000 | 20% | 50% | 14% |

| Massachusetts | 1,533,000 | 303,000 | 20% | 66% | 5% |

| Michigan | 2,156,000 | 665,000 | 31% | 56% | 10% |

| Minnesota | 1,216,000 | 257,000 | 21% | 51% | 12% |

| Mississippi | 664,000 | 285,000 | 43% | 35% | 25% |

| Missouri | 1,321,000 | 406,000 | 31% | 32% | 25% |

| Montana | 218,000 | 64,000 | 30% | 46% | 17% |

| Nebraska | 407,000 | 108,000 | 27% | 26% | 25% |

| Nevada | 686,000 | 203,000 | 30% | 40% | 22% |

| New Hampshire | 275,000 | 41,000 | 15% | 45% | 13% |

| New Jersey | 2,005,000 | 411,000 | 20% | 48% | 22% |

| New Mexico | 448,000 | 182,000 | 41% | 61% | 16% |

| New York | 4,525,000 | 1,233,000 | 27% | 61% | 10% |

| North Carolina | 2,321,000 | 757,000 | 33% | 34% | 26% |

| North Dakota | 158,000 | 37,000 | 23% | 28% | 19% |

| Ohio | 2,516,000 | 763,000 | 30% | 56% | 12% |

| Oklahoma | 861,000 | 314,000 | 36% | 27% | 31% |

| Oregon | 923,000 | 245,000 | 27% | 54% | 15% |

| Pennsylvania | 2,682,000 | 717,000 | 27% | 52% | 12% |

| Rhode Island | 230,000 | 56,000 | 24% | 63% | 11% |

| South Carolina | 1,095,000 | 391,000 | 36% | 34% | 25% |

| South Dakota | 174,000 | 46,000 | 27% | 30% | 21% |

| Tennessee | 1,500,000 | 506,000 | 34% | 45% | 18% |

| Texas | 6,707,000 | 2,227,000 | 33% | 23% | 42% |

| Utah | 750,000 | 186,000 | 25% | 22% | 23% |

| Vermont | 125,000 | 33,000 | 26% | 71% | 5% |

| Virginia | 1,906,000 | 446,000 | 23% | 29% | 24% |

| Washington | 1,669,000 | 367,000 | 22% | 49% | 14% |

| West Virginia | 373,000 | 140,000 | 38% | 65% | 9% |

| Wisconsin | 1,228,000 | 322,000 | 26% | 44% | 12% |

| Wyoming | 119,000 | 32,000 | 27% | 28% | 32% |

| NOTES: All data shown are among women ages 15-49, 2017. Low-income includes women living at or below 200% the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), which was $24,120 for an Individual in 2017. Some estimates are “N/A” because point estimates do meet the minimum standards for statistical reliability. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on 2017 Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. | |||||