A Look at Recent Proposals to Control Drug Spending by Medicare and its Beneficiaries

Overview

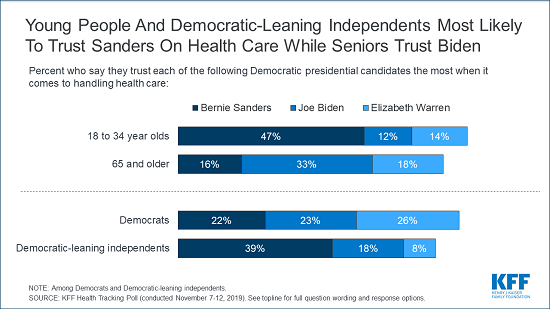

The affordability of prescription drugs is a pressing concern for many Americans, with broad agreement across the political spectrum that lowering prescription drug costs should be a top priority for Congress. The Trump Administration has put forward several proposals to address high and rising drug prices. Virtually all of the 2020 presidential candidates support efforts to lower drug prices1 , and key Congressional committees have marked-up legislation. Many of these proposals would directly affect prescription drug spending under Medicare, which accounts for 30 percent of national retail spending on drugs and nearly $1 out of every $5 in total Medicare spending (Figure 1).

Prescription drugs are an important component of health care for Medicare beneficiaries, which includes more than 60 million older adults and people with long-term disabilities. The majority of Medicare prescription drug spending is for drugs covered under Part D, the outpatient prescription drug benefit. Medicare Part B also covers drugs that are administered to patients in physician offices and other outpatient settings.

This brief describes proposed and recent changes to control Medicare drug spending and lower beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket drug costs. We include proposals from the Trump Administration and legislation introduced during the 116th Congress, including legislation passed out of the Senate Finance Committee, and legislation recently introduced by Speaker Pelosi and adopted by the committees of jurisdiction in the House (H.R. 3). We review the implications of these changes for various stakeholders and explain their estimated effects on Medicare and beneficiary spending, to the extent such effects are known, based primarily on estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

The brief focuses on drug pricing proposals related to Medicare specifically, rather than broader proposals that are not solely focused on Medicare, including those related to drug importation, expediting generic drug availability, patents, and price transparency.2 While we have made every effort to include the most recent proposals pertaining to Medicare drug costs, policy discussions are evolving rapidly. This brief will be updated as necessary in the future.

Overview of Proposed and Recent Changes

Proposed Changes

- Allow the government to negotiate drug prices

- Modify the Medicare Part D benefit design

- Establish an out-of-pocket spending limit and reallocate liability for catastrophic costs

- Exclude manufacturer discounts from the calculation of “TrOOP”

- Cap increases in Medicare drug prices to the rate of inflation

- Require rebates for Part D drugs with price increases faster than inflation

- Establish an inflation limit on Part B drug reimbursement growth

- Use international reference pricing for drugs covered by Medicare

- Make other modifications to payments for drugs covered under Part B

- Modify rebates under Part D

- Eliminate rebates under Part D (withdrawn by the Administration in July 2019)

- Share rebates with plan sponsors and/or beneficiaries

- Move coverage of some drugs from Part B to Part D

- Improve coverage for low-income Part D enrollees

- Eliminate cost sharing for generics for low-income subsidy enrollees

- Expand eligibility for low-income subsidies

Recent Changes

- Allow Medicare Advantage plans to require step therapy for Part B drugs

- Modify coverage requirements for drugs in Part D protected classes

- Require Part D plan sponsors to use real-time benefit tools

Issue Brief

Overview of Proposed and Recent Changes

Proposed Changes

- Allow the government to negotiate drug prices

- Modify the Medicare Part D benefit design

- Establish an out-of-pocket spending limit and reallocate liability for catastrophic costs

- Exclude manufacturer discounts from the calculation of “TrOOP”

- Cap increases in Medicare drug prices to the rate of inflation

- Require rebates for Part D drugs with price increases faster than inflation

- Establish an inflation limit on Part B drug reimbursement growth

- Use international reference pricing for drugs covered by Medicare

- Make other modifications to payments for drugs covered under Part B

- Modify rebates under Part D

- Eliminate rebates under Part D (withdrawn by the Administration in July 2019)

- Share rebates with plan sponsors and/or beneficiaries

- Move coverage of some drugs from Part B to Part D

- Improve coverage for low-income Part D enrollees

- Eliminate cost sharing for generics for low-income subsidy enrollees

- Expand eligibility for low-income subsidies

Recent Changes

Proposed Changes

Allow the Government to Negotiate Drug Prices

Under the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA), which established the Medicare Part D drug benefit, the federal government is prohibited from engaging in price negotiation or price setting on behalf of Medicare Part D beneficiaries. The MMA includes language known as the “noninterference” clause, which stipulates that the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) “may not interfere with the negotiations between drug manufacturers and pharmacies and PDP sponsors, and may not require a particular formulary or institute a price structure for the reimbursement of covered Part D drugs.” This is in contrast to how drug prices are established by other federal programs. For example, there is a statutory requirement for mandatory drug price rebates in Medicaid, and, in the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA), a drug manufacturer may not charge more than the lowest price paid by any private sector purchaser.

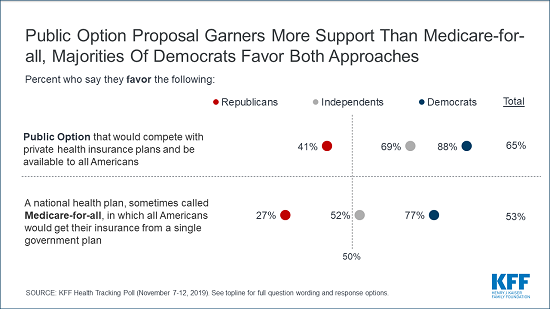

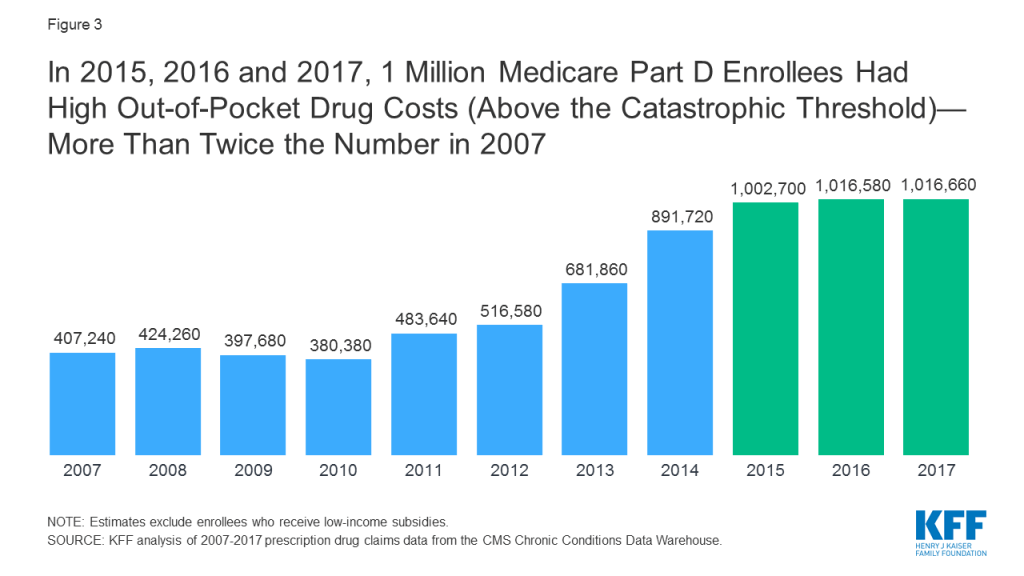

In the years since the enactment of the MMA, lawmakers have introduced legislation to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices, with the goal of lowering Part D program spending and enrollees’ out-of-pocket costs. Recent public opinion polls show strong and bipartisan support for allowing the federal government to negotiate drug prices in Medicare. During the 116th Congress, several members of Congress have introduced bills that would grant the Secretary authority to negotiate drug prices for Medicare Part D. Some are stand-alone bills, while others are incorporated in broader health reform legislation, including Medicare-for-all, public plan options, and Medicare buy-in proposals. Several Democratic presidential candidates have also endorsed this approach.

This summary focuses on five bills where the primary (or sole) purpose is to allow the Secretary to negotiate drug prices:

- H.R. 3, “Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act,” introduced by Speaker Pelosi and sponsored by Representatives Frank Pallone (D-NJ), Richard Neal (D-MA), and Bobby Scott (D-VA), the respective Chairmen of House Committees Energy & Commerce, Ways & Means, and Education & Labor (as passed out of Committees in October 2019)

- H.R. 1046/S. 377, “Medicare Negotiation and Competitive Licensing Act,” sponsored by Representative Lloyd Doggett (D-TX) in the House and Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) in the Senate

- H.R. 448/S. 99, ”Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Act,” sponsored by the late Representative Elijah Cummings (D-MD) in the House and Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) in the Senate

- S. 62, “Empowering Medicare Seniors to Negotiate Drug Prices Act,” sponsored by Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN)3

- H.R. 275, ”Medicare Prescription Drug Price Negotiation Act,” sponsored by Representative Peter Welch (D-VT)

While these bills seek to achieve the same overall goal of reducing drug prices by allowing the federal government to negotiate prices with drug manufacturers in Medicare, they take different approaches to achieve that end. The proposals vary in terms of how much direction is given to the Secretary regarding the negotiation process itself; whether any criteria are offered for which drugs and how many shall be negotiated; the factors to be considered in determining a negotiated price; provisions that aim to give the Secretary greater leverage to secure price concessions from drug manufacturers; and provisions that may apply in the event of unsuccessful negotiations.

The Pelosi legislation (H.R. 3) amends the non-interference clause under current law by adding an exception that allows for the price negotiation process established by the legislation. The negotiation process outlined in H.R. 3 would apply to a minimum of 25 and up to 250 brand-name drugs lacking generic or biosimilar competitors (including insulin), and would prioritize the 125 drugs with the highest Medicare Part D spending and 125 drugs with the highest spending in the U.S. (net of rebates). The minimum number of drugs subject to negotiation increases from 25 in the first year (2023) to 30 between 2028 and 2032 and 35 in 2033. Newly-approved drugs with prices at or above median household income may also be subject to negotiation, based on projected spending. The proposal establishes an upper limit for the negotiated price equal to 120% of the Average International Market (AIM) price paid by six economically prosperous countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom), and the negotiated price applies to both Medicare and commercial payers in group and individual markets. None of the other proposals explicitly mention an upper limit on the negotiated price, nor do they extend the Part D negotiated price to other payers. H.R. 3 imposes financial penalties on drug companies that do not comply with the negotiating process as well as in the event that negotiations fail. For example, manufacturers that fail to negotiate with the Secretary would face an escalating excise tax on the previous year’s gross sales of the drug in question, starting at 65% and increasing by 10% every quarter to a maximum of 95%.

The proposals introduced by Doggett/Brown (H.R. 1046/S. 377) and Cummings/Sanders (H.R. 448/S.99) call for much broader negotiations by the Secretary on behalf of Part D enrollees without defining how many drugs would be subject to negotiation, if not all Part D covered drugs. The Cummings/Sanders proposal also directs the HHS Secretary to establish a Part D formulary, a practice used by private plans in negotiating price discounts with manufacturers (not included in H.R. 3). In the event of unsuccessful negotiation between the Secretary and manufacturers, the Doggett/Brown proposal authorizes the Secretary to circumvent a manufacturer’s exclusivity rights and issue a competitive license to another manufacturer to produce a generic or biosimilar version of the drug for sale to Part D plans. The Cummings/Sanders proposal would use the lowest available price in either other federal programs or other specified countries as a fallback for the negotiated price in the event that negotiations between the Secretary and manufacturers are unsuccessful.

The legislation sponsored by Klobuchar (S. 62) and Welch (H.R. 275) simply strikes the non-interference clause, and in the case of the Welch bill, requires the Secretary to negotiate Part D drug prices, but neither proposal specifies further conditions or circumstances under which the negotiation should occur or fallback approaches in the event of unsuccessful negotiations.

The Senate Finance Committee considered an amendment to its drug pricing legislation that would have allowed the HHS Secretary to negotiate drug prices, but the amendment did not pass (12 ayes; 16 nays). The Trump Administration has not introduced its own proposal allowing HHS to negotiate drug prices in Medicare Part D, although President Trump endorsed this idea during his candidacy. (For more detail on Medicare drug price negotiation proposals, see What’s the Latest on Medicare Drug Price Negotiations?)

Budget Effects

In an October 2019 letter to Chairman Pallone, CBO provided a preliminary estimate of the effects of the drug price negotiation provisions of H.R. 3 on Medicare spending. CBO estimates the drug price negotiation provisions in H.R. 3 would achieve $345 billion in Medicare savings over the period between 2023 (the first year in which maximum fair prices would be used in Part D) and 2029. In its analysis of H.R 3, CBO indicates that the provision to levy an excise tax on drug companies that do not enter into negotiations or agree to the maximum fair price provides the Secretary with needed leverage to achieve lower drug prices and federal savings. CBO has not yet estimated the effects of H.R. 3 on private health plans, nor the effect of the negotiation provisions on out-of-pocket costs and premiums for Medicare Part D enrollees. (For more detail on CBO’s assessments of Medicare drug negotiation, see What’s the Latest on Medicare Drug Price Negotiations?)

This estimate represents a significant departure from prior estimates. In its initial assessments of the Medicare drug price negotiation concept in 2004 and 2007, CBO said that repealing the non-interference clause and allowing price negotiations between the Secretary and drug manufacturers would yield negligible savings, primarily because the Secretary would have insufficient leverage to secure price concessions; in May 2019, CBO reaffirmed its previous conclusions.

In contrast to H.R. 3 which applies pressure on drug manufacturers by imposing financial penalties on drug manufacturers that fail to negotiate with the Secretary, the Doggett/Brown bill relies instead on competitive licensing, and the Cummings/Sanders bill uses prices in other federal programs and other countries as a fallback. The degree to which these various approaches are effective in securing lower prices from drug manufacturers would have significant implications for Medicare program savings and for Medicare beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket drug costs. CBO has not yet estimated the potential savings attributable to the other bills discussed above.

Effects on Beneficiaries

In its analysis of drug price negotiation under H.R. 3, CBO expects that the lower drug prices resulting from this policy would lead to lower beneficiary premiums and cost-sharing (though CBO did not quantify the magnitude of this decrease). CBO also expects that this policy would lead to higher use of prescription drugs due to lower rates of medication non-adherence because of cost concerns. With greater medication adherence, CBO predicts this policy would lead to improved health outcomes for many beneficiaries, which would result in lower utilization and spending for other Medicare-covered services. In addition, people with private group and individual insurance would also likely see their drug costs decrease because the legislation requires manufacturers to offer the lower negotiated price to private payers or pay a civil monetary penalty.

Other Implications

CBO expects that this policy would lower revenues for drug manufacturers and lead to higher drug prices in other countries. CBO estimates that the loss in revenue for drug manufacturers would lead to lead to 8 to 15 fewer drugs coming to market over the next 10 years, of the approximately 300 drugs expected to be approved during this period. The decrease in the development of new drugs could negatively impact some beneficiaries, but CBO notes it is difficult to determine the type of drugs that would be affected and what their impact would be an overall health. For example, CBO did not specify whether these drugs would be breakthrough therapies or similar to treatments that are currently available.

Modify the Medicare Part D Benefit Design

The Medicare Part D standard benefit includes several phases, including a deductible, an initial benefit period, a coverage gap, and catastrophic coverage. Across these different benefit phases, the allocation of costs paid by Part D enrollees, plans, drug manufacturers, and Medicare varies.

Under the current structure of Part D, when enrollees reach the coverage gap benefit phase, they pay 25 percent of drug costs for brand-name drugs, plan sponsors pay 5 percent, and drug manufacturers provide a 70 percent price discount. The value of this discount counts towards the calculation of an enrollee’s “true out-of-pocket spending” (TrOOP), the amount used to determine when catastrophic coverage begins (at $6,350 in annual out-of-pocket spending in 2020, equivalent to an estimated $9,719 in total spending). Once enrollees pass through the coverage gap benefit phase and reach the catastrophic coverage phase, they pay 5 percent of their total drug costs, plans pay 15 percent, and Medicare pays 80 percent. The Medicare portion of catastrophic coverage costs, known as reinsurance, limits the financial risk for Part D plan sponsors associated with higher-cost enrollees.

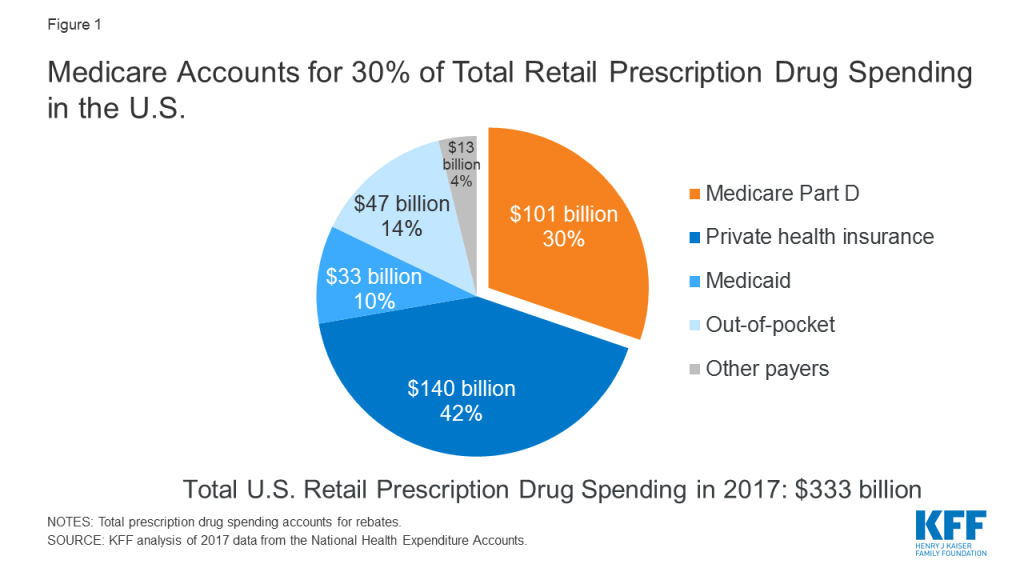

In recent years, policymakers have expressed concerns about the absence of a hard cap on out-of-pocket spending for Part D enrollees, a significant increase in Medicare reinsurance spending, and the allocation of financial responsibility for drug costs among plan sponsors, pharmaceutical companies, the Medicare program, and Part D enrollees. The Trump Administration’s FY 2020 Budget, the Senate Finance Committee legislation, and H.R. 3 all include provisions to address this concern, with some differences.

Establish an out-of-pocket spending limit and reallocate liability for catastrophic costs

In its FY 2020 budget, the Administration proposed establishing an out-of-pocket spending limit in Part D by phasing down beneficiary coinsurance in the catastrophic phase from 5 percent to 0 percent (i.e., no cost sharing) over four years, beginning in 2020.4 The Administration’s proposal to add an out-of-pocket spending limit is paired with another proposal that would increase Part D plans’ share of catastrophic coverage costs from 15 percent to 80 percent, and decrease Medicare’s share from 80 percent to 20 percent.5 ,6

The Senate Finance Committee’s drug pricing legislation that was voted out of committee includes a provision to establish a cap on out-of-pocket spending and reallocate costs in the catastrophic phase. The cap on beneficiary out-of-pocket spending is initially set at $3,100 in 2022. For costs above the catastrophic threshold, the proposal reduces Medicare reinsurance payments from 80 percent to 20 percent, increases plans’ share from 15 to 60 percent, and requires drug manufacturers to pay 20 percent, instead of providing discounts in the coverage gap, which would be phased out. The proposed changes to the Medicare benefit design would be phased in over a three-year period, from 2022 to 2024.7

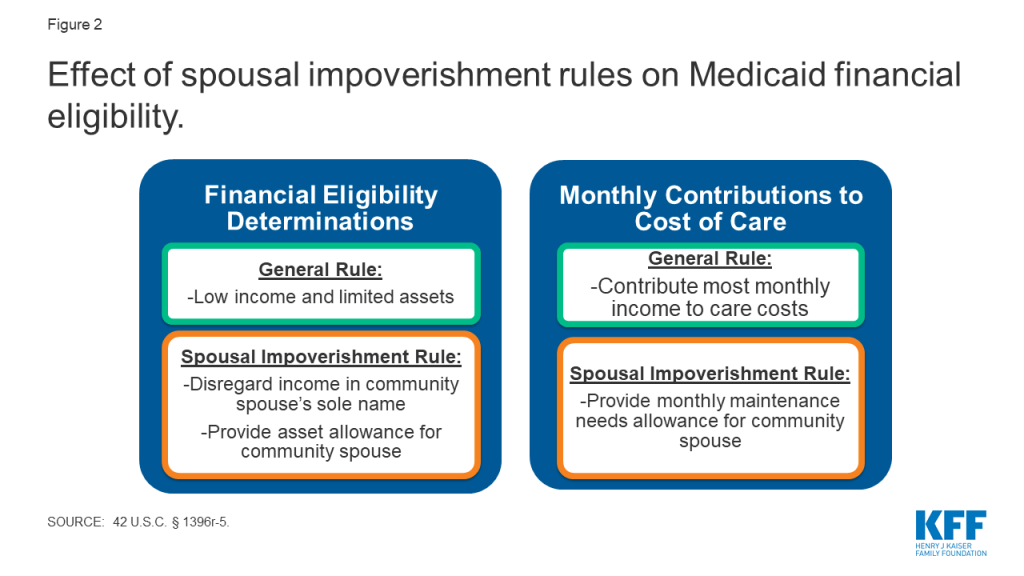

The drug price legislation introduced by Speaker Pelosi and voted out of three committees (H.R. 3) includes a provision to place a cap on out-of-pocket drug spending and reallocate liability for costs above the catastrophic threshold, but at somewhat different levels than the related provision in the Senate Finance Committee legislation. The cap on beneficiary out-of-pocket spending is initially set at $2,000 in 2022. For costs above the catastrophic threshold, the proposal reduces Medicare reinsurance payments from 80 percent to 20 percent, increases plans’ share from 15 to 50 percent, and requires drug manufacturers to pay 30 percent, instead of providing discounts in the coverage gap, which would be phased out. (Figure 2) Manufacturers would also be required to pay 10 percent of the costs in the initial coverage gap phase.8 As amended, H.R. 3 also includes a provision that would allow enrollees who reach the out-of-pocket cap of $2,000 in one prescription to smooth out their drug costs over the course of the year.

Budget Effects

Because the Administration’s FY 2020 budget combines proposals to add an out-of-pocket spending limit to Part D and reallocate costs for catastrophic coverage, the budget effects of these proposals are estimated together. According to CBO, these proposals are expected to decrease Medicare spending by $1.8 billion over 10 years. Estimated savings would be generated by shifting reinsurance costs from Medicare to plan sponsors. It is expected this shift would give plans stronger incentives to lower costs.

In contrast to CBO, the Administration estimates that its proposals would increase federal spending by $14.0 billion over 10 years. Spending could increase under these proposals if federal savings that result from reducing Medicare reinsurance payments do not offset higher spending from adding an out-of-pocket spending limit. Neither the CBO nor the Administration’s estimate included the budget impact on beneficiaries.

According to CBO’s preliminary estimate, the Senate Finance Committee’s Part D benefit redesign proposal would generate savings of $34.6 billion for Medicare over 10 years (2020-2029). Estimated Medicare savings are greater under the Senate Finance proposal than under the Administration’s proposal because both Part D plans and drug companies would have financial incentives to lower costs. Requiring drug companies to pay a portion of costs above the catastrophic threshold (20% in the Senate Finance Committee proposal) could create incentives for manufacturers to lower the price of specialty and other high-priced drugs. Requiring plans to pick up a larger share of costs above the catastrophic threshold (60% in the Senate Finance Committee proposal) is likely to create stronger incentives for plans to manage costs throughout all phases of the benefit.

There is no CBO score yet available for the H.R. 3 provisions related to Part D benefit restructuring.

Effects on Beneficiaries

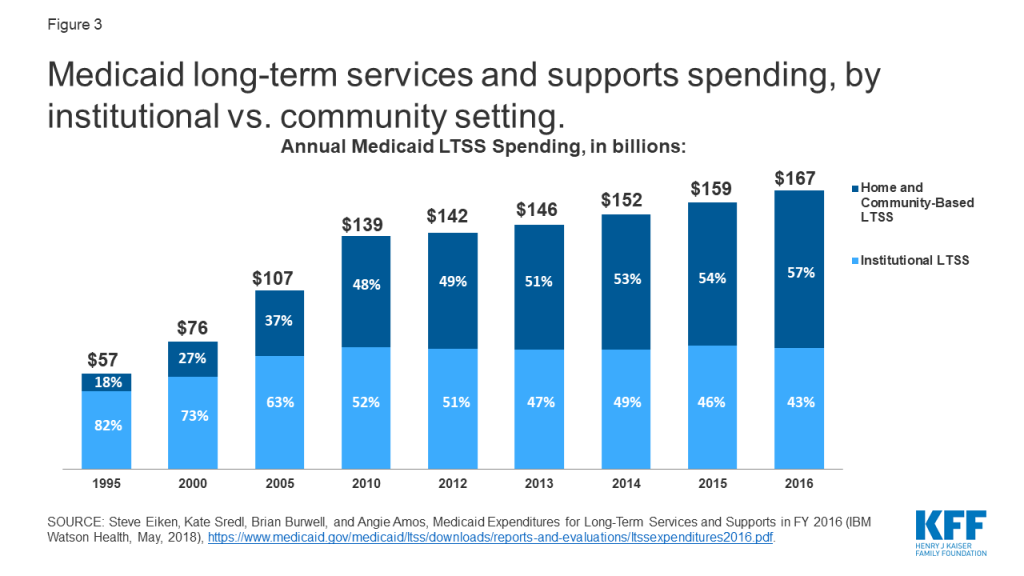

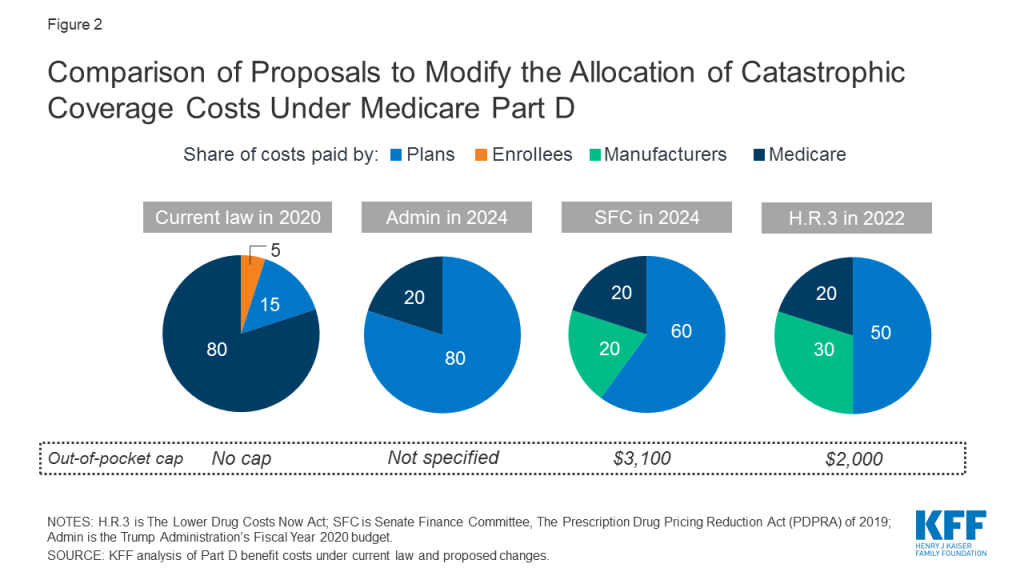

Adding an out-of-pocket spending limit in Part D would provide substantial savings for beneficiaries who have high drug costs. In 2017, over one million Part D enrollees had out-of-pocket spending in the catastrophic phase (Figure 3). Beneficiaries with out-of-pocket spending above the catastrophic threshold may be taking one high-cost drug, for conditions such as cancer, multiple sclerosis and Hepatitis C, or multiple relatively expensive drugs.

All three of these proposals – the Trump Administration’s, the Senate Finance Committee’s and H.R.3 – would limit the financial exposure of Medicare beneficiaries, though as noted above, CBO has not estimated the effects of an out-of-pocket limit by itself.

In its preliminary analysis, CBO estimates that the Senate Finance Committee’s benefit redesign proposal, which includes an out-of-pocket spending limit among other features, would reduce beneficiary spending on cost sharing by $20 billion and premiums by almost $1 billion over the 10-year period. There is no similar estimate yet available from CBO for H.R. 3, although presumably the effects would be within the same range for both proposals.

Proposals that shift more financial risk to plan sponsors and pharmaceutical companies by increasing their share of costs in the catastrophic phase could also affect beneficiaries. Plans would have stronger incentives to control costs and minimize their liability by, for example, attempting to negotiate lower drug prices with pharmaceutical companies. Plans would also have stronger incentives to steer beneficiaries toward lower-cost medications, which could lower beneficiaries out-of-pocket costs. At the same time, plans may impose new formulary restrictions and cost management tools, which could potentially affect beneficiaries’ access to needed medications. It is also possible that plans could increase Part D premiums to offset the additional costs they incur above the catastrophic threshold, although the CBO’s preliminary estimate indicates that the effects of this proposal, on its own, would have only a modest impact on premiums.

Exclude Manufacturer Discounts from the Calculation of “TrOOP”

The Administration has proposed changing the calculation of enrollees’ out-of-pocket costs (TrOOP) to exclude the value of the manufacturer price discount on brand-name drugs filled in the coverage gap benefit phase. Under current law, the value of the discount is included in the calculation of out-of-pocket spending, which means that Part D enrollees move through the coverage gap benefit phase more rapidly and qualify for catastrophic coverage sooner than they otherwise would. The Administration’s rationale for this proposal is to “correct the misaligned incentive” that currently exists for plans when enrollees use more costly drugs and reach the catastrophic coverage phase sooner, because plans’ liability for costs during that phase is relatively low.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has also recommended this change in conjunction with adding an out-of-pocket limit to Part D and reducing Medicare’s reinsurance payments above the catastrophic threshold as described above. Some policymakers have suggested pairing the change in the calculation of TrOOP with one that would lower the catastrophic threshold so that beneficiaries are held harmless in terms of their total annual out-of-pocket liability (since removing the manufacturer discount from the TrOOP calculation would increase beneficiary out-of-pocket spending, as discussed below).

The Senate Finance Committee’s drug pricing legislation does not explicitly address the TrOOP calculation. However, because the coverage gap phase would be eliminated and there no longer would be a manufacturer discount in that phase, this would effectively change the TrOOP calculation. H.R. 3 sunsets the existing coverage gap discount program and the provision that the current manufacturer discount counts towards TrOOP, and does not include a requirement that the new 10 percent discount below the catastrophic coverage threshold would count towards TrOOP.

Budget Effects

CBO estimates that the Administration’s FY 2020 budget proposal to change the calculation of TrOOP by excluding the value of the manufacturer discount would reduce Medicare spending by $73.2 billion over 10 years. The CBO score indicates that plan costs would decrease substantially and enrollees would be responsible for the out-of-pocket costs in the coverage gap benefit phase leading to fewer enrollees progressing through the coverage gap benefit phase and into catastrophic coverage, and fewer enrollees ultimately reaching the catastrophic phase.

Effects on Beneficiaries

Under the Administration’s proposal, Part D enrollees would face higher out-of-pocket costs before reaching the out-of-pocket limit if the value of the manufacturer discount is excluded from the TrOOP calculation, and would progress through the coverage gap benefit phase at a slower pace. This would result in fewer enrollees incurring out-of-pocket costs that exceed the catastrophic threshold, which means that fewer would benefit from an out-of-pocket limit. However, if the out-of-pocket limit was lowered, as is proposed under the Senate Finance Committee legislation and under H.R. 3, beneficiaries might not incur higher out-of-pocket costs.

Higher out-of-pocket costs could lead to a decrease in medication adherence, as well as lower utilization. In its estimate of H.R. 3, CBO noted that improved adherence would lead to improved health outcomes and lower spending for other Medicare-covered services. If plan costs decrease as a result of changing the TrOOP calculation, plan premiums and Medicare spending on premium subsidies could also decrease. However, for people with high drug costs, the increase in out-of-pocket spending associated with the change in the TrOOP calculation would likely exceed the level of savings they would receive in the form of lower premiums.

Cap Increases in Medicare Drug Prices to the Rate of Inflation

For the past decade, annual price increases on brand-name drugs have far outpaced the rate of inflation.9 To address these concerns, the Administration and members of Congress are considering proposals to place a cap on annual price increases for drugs covered under Medicare at the rate of inflation (Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, or CPI-U), or require manufacturers to pay a rebate to Medicare if their prices increase faster than the inflation rate. The Medicaid program has a similar policy in place whereby manufacturers are required to provide a rebate to the Medicaid program if the price of a prescription drug increases faster than the rate of inflation. In the case of the Trump Administration, the policy is limited to Part B drugs only whereas the Congressional proposals apply more broadly to Parts B and D.

Require Rebates for Part D Drugs with Price Increases Faster than Inflation

The Senate Finance Committee legislation includes a provision to require manufacturers of Part D drugs and biologics to pay a rebate to Medicare if prices increase faster than inflation. (The Committee voted down an amendment to strike this provision by a tie vote, 14-14.) The Committee proposal would only apply to brand-name drugs covered under Part D, and would measure price changes based on the list price (wholesale acquisition cost). Manufactures would have 30 days to pay the requisite rebate or would face a civil monetary penalty of the original rebate amount plus 25 percent. The measurement of price changes would look back to July 1, 2019, and the proposal would take effect January 1, 2022.

H.R. 3 includes a similar provision that requires manufacturers to pay a rebate if Medicare drug prices increase faster than the rate of inflation. Under this proposal, any manufacturer that increases the price of Part D drugs faster than the rate of inflation would be required to pay the difference in the form of a rebate to Medicare. However, unlike the Senate Finance Committee’s proposal, H.R. 3 would apply to all drugs, not just brand and biologics, and would use the average manufacturer price to measure drug prices, not the wholesale acquisition cost. Manufacturers that do not pay the requisite rebate amount within 30 days would be required to pay a penalty equal to 125 percent of the original rebate amount. H.R. 3 would measure price changes going back to January 1, 2016 (compared to 2019 in the Senate Finance Committee legislation), and the proposal would take effect in 2022. (See below for a discussion of the Part B drug rebate provisions included in the Senate Finance Committee and H.R. 3.)

Budget Effects

According to its preliminary estimate, CBO expects the Senate Finance Committee’s proposal would achieve $57.5 billion in Medicare savings over 10 years (2020-2029).

There is no CBO score yet available for the Part D rebate provision in H.R. 3.

Effects on Beneficiaries

In its preliminary analysis, CBO estimates that the Senate Finance Committee’s inflation rebate proposal would reduce beneficiaries’ spending on cost sharing by $5 billion and premiums by $5 billion over the 10-year period. (CBO has not yet provided a similar estimate for this provision in H.R. 3.) Requiring manufacturers to pay an inflation rebate to Medicare if their Part D drug prices increase faster than inflation could be expected to slow the growth in beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket drug costs over time if manufacturers limit price increases to the rate of inflation. It could also help beneficiaries better anticipate their out-of-pocket costs from one year to the next. If the inflation rebate proposal helps to limit the growth in Part D drug prices, it could also lower Part D plan sponsor costs, which could lower Part D premiums for enrollees.

The inflation rebate provisions in the Senate Finance Committee legislation and H.R. 3, on their own, would not automatically reduce drug prices from their current levels and would not automatically lead to lower out-of-pocket spending by enrollees. However, under both proposals, there is the potential for manufacturers to respond to the rebate requirement by lowering drug prices to the level they would have been if they had only increased at the rate of inflation. For example, under H.R. 3, this could lower out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries who take drugs that have increased faster than the rate of inflation since 2016, if their costs are calculated based on the drug’s price (as under coinsurance). However, manufacturers may instead choose to pay the required rebate instead of reducing prices from their current levels.

Under both of these proposals, drug manufacturers may respond to the inflation rebate by increasing launch prices, which could result in some beneficiaries paying higher prices for new drugs, and potentially lead to higher costs for other payers and privately-insured patients. While plans have the ability to negotiate with companies and can refuse to cover drugs with very high launch prices, they may have less leverage in some instances, such as when there are no therapeutic alternatives available. It has also been argued that requiring inflation rebates could stifle innovation, which could affect access to new therapies. (These arguments apply similarly to the Part B inflation rebate proposal discussed below.)

Establish an inflation limit on Part B drug reimbursement growth

Medicare covers a more limited set of prescription drugs under Part B than under Part D, which are typically administered in outpatient settings such as physicians’ offices and hospital outpatient departments. These drugs are generally used in the treatment of serious illnesses such as cancer, multiple sclerosis, and other high-cost conditions. For most Part B drugs, providers are reimbursed based on the average sales price (ASP) of a given drug plus a 6 percent add-on payment. (Under the budget sequester, payments to providers for Part B drugs were reduced, resulting in a net payment of ASP plus 4.3 percent beginning in April 2013.) Both the Trump Administration and MedPAC have expressed concern that the current payment system creates incentives that contribute to higher Part B drug costs due to lack of price competition for certain drugs and because physician reimbursement is higher for higher-priced drugs.

As one of several modifications to payments for Part B drugs, the Administration has proposed placing an inflation-adjusted limit on payment for Part B drugs by capping the growth of the ASP payment rate for Part B drugs at the rate of inflation.10 Drugs would be paid either at the current ASP payment rate or at the inflation-adjusted ASP payment rate, whichever is lower. (For a discussion of the Administration’s other Part B drug payment proposals, see Use International Reference Pricing for Drugs Covered by Medicare and Make Other Modifications to Payments for Part B Drugs below.)

The Senate Finance Committee includes an inflation rebate proposal for Part B drugs, similar to the approach for Part D discussed above. If the average sales price for single source drugs and biologics (though not biosimilars), covered under Part B increase faster than the rate of inflation, manufacturers would be required to pay the difference in the form of a rebate to Medicare. Manufacturers that do not to pay the rebate within 30 days would face a monetary penalty equal to 125 percent of the rebate amount. Manufacturers that fail to pay the monetary penalty would not receive any payment for that drug under Part B until the penalty is paid. The measurement of price increases would look back to July 1, 2019, and would take effect on January 1, 2021.

The provision in H.R. 3 to establish an inflation rebate for Part B drugs is similar to the provision in the Sentence Finance Committee legislation. If the average sales price for single source drugs, biologics, as well as biosimilars, covered under Part B increase faster than the rate of inflation, manufacturers would be required to pay the difference in the form of a rebate to Medicare. Manufacturers that do not to pay the rebate within 30 days would face a monetary penalty equal to 125 percent of the rebate amount. However, unlike the Senate Finance Committee proposal, there is no provision that prevents payment for Part B drugs until the penalty is paid. The measurement of price increases would look back to January 1, 2016 (compared to 2019 in the Senate Finance Committee legislation), and the proposal would be implemented on July 1, 2021.

Budget Effects

CBO stated there was not enough detail to score the Administration’s proposal to limit Part B drug price growth to the rate of inflation. The Administration also did not estimate its potential budget impact.

In its preliminary estimate, CBO projects that the Senate Finance Committee’s inflation rebate proposal for Part B drugs would decrease Medicare spending by $10.7 billion over 10 years (2020-2029).

There is no CBO score yet available for the Part B rebate proposal in H.R. 3.

Effects on Beneficiaries

The underlying price of drugs covered under Part B affects beneficiary out-of-pocket spending because beneficiaries are required to pay 20 percent coinsurance for Part B drugs. Unlike most health insurance coverage, traditional Medicare does not have an annual cap on out-of-pocket spending, although many beneficiaries currently have a limit on their out-of-pocket costs, either through a supplemental policy that covers cost sharing, (such as Medigap), or if they are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, which are required to have an out-of-pocket limit.

Capping growth of Part B drug reimbursement to the rate of inflation could slow the growth in beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs for Part B drugs and lead to greater stability over time. Lower overall drugs costs could also result in lower Part B premiums and lower premiums for supplemental coverage that pays Part B cost sharing. This proposal would not directly lower the current high cost of many Part B drugs, however, but as mentioned previously in relation to the Part D inflation rebate proposal, manufacturers may choose to limit the increase in drug prices below the rate of inflation, to avoid paying a rebate. Limiting the increase in Medicare’s payments for drugs to the rate of inflation may lead companies to launch drugs at higher prices, which could increase costs for some beneficiaries. CBO’s estimate of the Senate Finance Committee proposal did not project the effects of the Part B inflation rebate on Part B premiums.

Use International Reference Pricing for Drugs Covered by Medicare

Many studies have shown that the United States pays more for drugs than other developed countries, on average.11 Several proposals have been introduced to align drug prices in the United States more closely with drug prices in other countries in order to lower drug costs. The Trump Administration has suggested using international reference pricing specifically for Part B drugs, while some Congressional proposals apply more broadly, including, but not limited to, drugs covered by Medicare.

In an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM), the Administration proposed to test a series of new approaches for reimbursing Part B drugs, one of which is sometimes referred to as the international price index (IPI) model.12 ,13 Under the IPI model, Part B drug payments would be based on an international reference price instead of ASP, except in situations where ASP is lower. The target prices would be derived from an international price index, which would be phased in over a five-year time period. The IPI model would be tested and its effectiveness evaluated using a randomized design in geographic areas that comprise 50 percent of Part B spending. Medicare would aim to reduce Part B drug payments to 126 percent of what other countries pay, compared to 180 percent currently.14 The Senate Finance Committee voted on an amendment to prevent implementation of this model, but it narrowly failed by a tie vote.

There are several Congressional proposals that would use international reference prices to limit prescription drug prices both for Medicare Part B and Part D and for other payers. Under one proposal introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT), the price of brand-name drugs would be limited to the median price in Canada, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan; if companies’ drug prices exceeded this amount, the government would waive the companies’ patent and exclusivity rights for those drugs and allow other manufacturers to produce them.15 Under another proposal introduced by Senator Rick Scott (R-FL), drug manufacturers would be prohibited from charging a higher list price for both brand-name and generic drugs than they do in Canada, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, or Japan. As mentioned previously, H.R. 3 would use international reference pricing to set an upper limit on Medicare prices for drugs that have been selected for negotiation by the HHS Secretary, not to exceed 120 percent of the average price in up to six specified countries – Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

Budget Effects

The Administration estimates that its proposed IPI model for Part B drug reimbursement would reduce federal Medicare spending by $17.9 billion over five years (2020-2025). There are many uncertainties around this estimate, however, and behavioral responses by a variety of stakeholders, including beneficiaries, manufacturers, and providers, would significantly affect the model’s financial effects. The Administration noted in the ANPRM that its estimate is likely to change. CBO has not scored the Administration’s proposal, nor any of the international reference pricing proposals that would apply more broadly.

Effects on Beneficiaries

The Administration estimates that Medicare beneficiaries could save $3.4 billion over five years under its Part B international reference pricing proposal due to decreased coinsurance that would result from lower list prices. However, some have indicated that not all beneficiaries would experience savings because many have supplemental insurance (Medigap, retiree health benefits, and Medicaid) that covers cost sharing for Part B drugs. Reduced prices for Part B drugs may lead to lower Part B costs overall, which could lead to a reduction in Part B premiums and premiums for supplemental coverage, along with a decrease in Medicaid spending on behalf of dually eligible beneficiaries who take Part B drugs. This proposal would not affect drug costs and spending under Medicare Part D.

Under broader international reference pricing proposals, Medicare beneficiaries could experience cost savings due to lower costs under Parts B and D. This could take the form of lower cost sharing for drugs covered under both Part B (if beneficiaries do not have supplemental coverage that covers cost sharing) and Part D, particularly for non-preferred drugs where beneficiaries could pay up to 50 percent of the cost of a specialty drug as well as above the catastrophic threshold where beneficiaries pay 5 percent of drug costs. Lower drug prices overall could also reduce Part B costs, which would reduce Part B premiums, as well as lower Part D plan costs, which could result in lower Part D premiums.

Other Implications

The Administration’s rationale for the IPI proposal is to “cut down on foreign governments’ freeriding,” by “securing for the American people a share of the price concessions that drug makers voluntarily give to other countries.” Analysis by the Administration’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning (ASPE) showed that, for the 27 highest-cost Part B drugs, acquisition costs in the United States were 1.8 times higher than those in 16 other developed countries. However, some question the assertion that using international benchmark prices would reduce costs, arguing that pharmaceutical companies may simply refuse to sell a drug at the new target price, and Medicare would have little recourse with regard to enforcement due to its coverage requirements. Drug manufacturers may also find ways to adjust foreign prices that could undercut savings on U.S. drug prices.16

Similar issues would arise for the international reference pricing proposals that apply broadly (not limited to Part B only). Without some sort of enforcement mechanism, manufacturers may refuse to comply with these rules to sell a drug at a new lower price, and Medicare would still be required to cover the drug. At the same time, if manufacturers face a financial penalty for non-compliance, such as a tax or loss of exclusivity rights, they may have a strong incentive to increase prices in other countries to avoid serious financial losses. These tactics may ultimately lead to lower-than-anticipated savings.

Make Other Modifications to Payments for Part B Drugs

In addition to the Part D drug payment proposals outlined above, the Administration, the Senate Finance Committee, and other policymakers have proposed other modifications to payments for Part B drugs that aim to lower beneficiary out-of-pocket costs, decrease Part B drug spending, and address incentives within the current payment system that may lead to utilization of more expensive drugs even when less expensive alternatives are available.17 (H.R 3 does not include any other provisions related to Part B drug payment changes aside from the inflation rebate provision.)

The Administration’s ANPRM includes a provision to eliminate the ASP percentage-based add-on payments to physicians under Part B. As mentioned previously, under budget sequestration, providers are currently reimbursed at ASP plus a 4.3 percent add-on, rather than ASP plus 6 percent.18 The ANPRM provision would effectively raise the add-on payment back to the full 6 percent, but would change the form of reimbursement for the add-on payment to a fixed payment amount for physician-administered drugs, instead of the 6 percent add-on. This add-on payment would not vary with the underlying price of the drug, unlike the current ASP plus 6 percent payment.19

In its drug pricing legislation, the Senate Finance Committee proposed a number of changes to the Part B drug payment system. While these provisions differ in their specifics from the Administration’s proposals, they are designed to achieve similar goals. For example, in order to mitigate the financial incentive for physicians to prescribe higher-priced drugs, the Committee proposed to establish a maximum add-on payment of $1,000 for drugs, biologics, and biosimilars; currently there is no limit to the add-on payment amount that providers can receive. The legislation also includes a number of provisions that would modify how ASP is calculated, which are designed to reduce excess payments for Part B drugs by Medicare. For example, the Committee proposed to require manufacturers to exclude the value of coupons from the calculation of ASP; presently, manufacturers are not required to exclude the value of coupons or certain price concessions they provide to patients in the calculation of ASP, which results in higher Medicare reimbursements for Part B drugs.

Budget Effects

According to the Administration’s estimate for the ANPRM, the proposed changes to physician payments for Part B drugs would increase Medicare spending by $1.6 billion because payments to physicians under the proposed system of fixed amounts for the add-on payment would increase from the current add-on payment based on ASP plus 4.3 percent.

In its preliminary estimate, CBO projects that the Senate Finance Committee’s proposed changes to Part B drug payments would generate savings of $2.2 billion for Medicare over 10 years (2020-2029) (in addition to the $10.7 billion in projected savings from the Part B drug inflation rebate). The largest component of this estimate is the provision to exclude the value of coupons from ASP (estimated savings of $1.45 billion over 10 years), due to the reduction in Medicare payments for Part B drugs associated with lower ASP amounts.

Effects on Beneficiaries

All of these proposals aim to lower Part B drug prices, reduce excess payments that drive up Part B drug and program costs, and eliminate incentives for providers to prescribe higher-priced drugs. If payments to providers are disconnected from the price of drugs they administer, and if patients receive lower-priced drugs as a result, then beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs would be lower. Coinsurance would also be lower if the value of ASP for specific drugs declines. As discussed previously, however, Medicare beneficiaries with supplemental insurance may not experience a direct cost reduction because their Part B coinsurance is covered. At the same time, lower overall Part B costs due to reduced Part B drug prices could also lower Part B premiums for all beneficiaries.

Modify Rebates under Part D

Currently, section 14 of the Medicare and Medicaid Patient and Program Protection Act of 1987 requires the Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) to establish “safe harbors”, which exempts certain business or payment practices from criminal penalties under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute. One of the safe harbor practices protected by the OIG rule are rebate payments made by drug manufacturers to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and health plan sponsors. Under the current drug pricing system, pharmaceutical companies offer rebates to PBMs in exchange for preferred formulary placement of their drug over their competitors’ products, which helps to lower Part D plan and program costs.20 These rebates produce lower net drug prices for payers which enables them to offer lower premiums in turn. Rebates do not directly lower out-of-pocket costs for Part D enrollees, however, because any rebates negotiated for the drugs they take are not passed on at the point of sale.

Eliminate Rebates under Part D (withdrawn by administration in July 2019)

Under the Trump Administration’s February 2019 proposed rule, which was withdrawn in July 2019, rebate payments by drug manufacturers to PBMs, Medicare Part D plan sponsors, and Medicaid managed care organization (MCO) plan sponsors would have been excluded from the safe harbor protections. The rule also proposed two new safe harbor protections: one which would have allowed drug manufacturers to provide discounts that would apply to beneficiaries’ point of sale purchases, and another which would have authorized fixed fee arrangements for certain services between drug manufacturers and PBMs.

Budget Effects

According to CBO, this proposal would have increased federal Medicare spending by $177 billion over 10 years, due to increases in federal subsidies for premiums and for low-income cost sharing. Similarly, OACT estimated this proposal would have increased federal Medicare spending by $196 billion over 10 years (2020-2029).21 Both CBO and OACT assumed that with the elimination of rebates, pharmaceutical manufacturers would alter their pricing and rebate strategies. With the loss of rebate revenue, plans may have raised their premiums, which would have led to increased premium subsidies paid by the federal government, resulting in greater overall costs for the Medicare program. Others noted the possibility that varied stakeholder responses to the proposal could have potentially led to increases or decreases in overall federal spending that were impossible to predict.22

Effects on Beneficiaries

According to CBO, Part D premiums were likely to rise under this proposal, based on the assumption that bids from Part D plans would increase in the absence of rebates. OACT projected that the majority of beneficiaries would have seen an increase in their total out-of-pocket spending and premium costs of $58 billion over 10 years.

Both CBO and OACT predicted that a small group of beneficiaries who use drugs with significant manufacturer rebates might have seen a decline in their overall out-of-pocket spending due to decreased cost sharing at the point of sale. Lower out-of-pocket costs under this proposal could have led to increased medication adherence for affected beneficiaries and potentially could have reduced the incidence of costly, emergent medical events.23 However, premiums would have modestly increased for all beneficiaries, driving up total spending for most people covered by Medicare.

If manufacturers did not offer rebates at the point of the sale as large as the ones they currently offer to PBMs and plan sponsors, savings for beneficiaries who use the specific drugs that currently have substantial rebates would have been lower than estimated. Additionally, beneficiaries who do not use drugs that have significant manufacturer rebates would not have benefited from this proposal (and would have incurred higher Part D premiums). According to one industry-funded analysis, only 36 percent of brand drugs overall have manufacturer rebates, which indicates that many beneficiaries would not have seen savings.24

Other Implications

The Administration’s rationale for eliminating rebates was to better align incentives in order to “curb list price increases, reduce financial burdens on beneficiaries, lower or increase Federal expenditures, and improve transparency.” Eliminating rebates may have also altered other features of Part D formulary design, such as existing incentives for plans or PBMs to give preferred formulary placement to higher-cost drugs with higher associated rebates and/or provide less favorable coverage of lower-cost products that have low or no rebates.25 Those in support of the rebate proposal argued that it would have prevented PBMs from favoring high-cost drugs with high list prices, incentivized manufacturers to lower list prices in exchange for better formulary placement, and encouraged savings to be passed on to the consumer at the point of sale.26

There was much uncertainty over whether eliminating rebates in Part D would have the intended effect or instead result in both higher Part D premiums and higher out-of-pocket spending for beneficiaries and increased spending for the federal government. Some critics of the proposal contended that it did not create any incentives for manufacturers to lower list prices, particularly if rebates in the commercial market were still allowed, which may have left beneficiaries paying as much or more out of pocket without PBMs negotiating on their behalf.27 CBO likewise stated that it did not expect manufacturers to lower list prices as a result of this proposal. Some skeptics also questioned whether the proposed safe harbor to allow certain fixed fee arrangements between drug companies and PBMs would have had unintended effects, as plans and manufacturers adopted alternative arrangements that may have formed a de facto system of rebates.

Share Rebates with Part D Plan Sponsors and/or Beneficiaries

Rather than eliminate rebates entirely, some policymakers have proposed to require that PBMs share rebates with Part D plan sponsors and/or enrollees. One Congressional proposal introduced by Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), would require a minimum percentage of rebates to be passed through to plan sponsors and patients. In its FY 2019 budget, the Administration included a proposal to pass at least one-third of all rebates and price concessions to enrollees at the point of sale, but the proposed rule to remove the safe harbor for rebates (which was withdrawn) superseded that approach.28

Budget Effects

CBO has not scored these proposals.

Effects on Beneficiaries

Proposals to share rebates with plan sponsors and/or patients have the potential to lower out-of-pocket costs for Part D enrollees, since cost sharing would be based on a lower price. However, manufacturers and plan sponsors could potentially take compensatory actions to lower the overall rebate amount, in which case savings to beneficiaries would be reduced.

Move Coverage of Some Drugs from Part B to Part D

In its FY 2020 budget, the Administration proposed authorizing the HHS Secretary to shift coverage of certain drugs currently covered under Part B to Part D, beginning in 2020, subject to a determination that savings could be gained from shifting from the ASP plus 6 percent reimbursement under Part B to negotiated pricing under Part D. The Secretary would not use this authority if doing so would limit patient access to a drug or if beneficiary cost sharing would increase. In order for this proposal to be implemented, a new billing mechanism may need to be established between Part D plans and Part B prescribers. The rationale for this proposal is to “allow HHS to leverage Part D plans’ negotiating power to bring down prices and lower patient out-of-pocket costs.”

The Senate Finance Committee legislation also has a provision that requires MedPAC to produce a report that analyzes the effects of shifting coverage of some Part B drugs to Part D. The report would look at the impact of this shift on program spending and beneficiary cost sharing as well as the feasibility and policy implications of such an approach.

Budget Effects

CBO stated it lacked sufficient detail to score this proposal, and the Administration did not produce a budget estimate.

Effects on Beneficiaries

This proposal could lead to lower out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries if Part D plan sponsors are able to negotiate lower prices for drugs that are currently covered under Part B. In addition, beneficiaries with Medigap might see a reduction in their premiums, because Medigap would no longer be covering the 20 percent coinsurance for these drugs under Part B.

Improve Coverage for Low-Income Part D Enrollees

Under current law, Medicare beneficiaries with low incomes and modest assets are eligible to receive subsidies to help cover their Part D monthly premiums and cost-sharing amounts through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program. Some beneficiaries automatically qualify for the LIS, while those who do not can apply and will qualify for full subsidies if their income falls below 135 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($16,862 individuals/$22,829 couples in 2019) and their assets do not exceed $9,230 ($14,600 if married). Those with incomes at or below 150 percent FPL ($18,735 individuals/$25,365 couples in 2019) and assets between $9,230 and $14,390 ($14,600 and $28,720 if married) qualify for partial subsidies.29

LIS enrollees currently pay low cost-sharing amounts for brand-name and generic drugs. Enrollees receiving full subsidies pay $1.25 for generics and $3.80 for brands in 2019, and those receiving partial subsidies pay $3.40 and $8.50, respectively. Because the cost differential between brands and generics is relatively small, there is some concern that LIS enrollees do not face a strong financial incentive to use generic drugs. This may result in higher costs for LIS enrollees who use brands when generics are available, as well as higher costs for Medicare, which subsidizes a large portion of cost sharing for LIS beneficiaries.

Eliminate Cost Sharing for Generics for LOW-INCOME SUBSIDY ENROLLEES

Under a provision in H.R. 3, cost sharing for generic drugs, including multiple source drugs, would be eliminated for Part D LIS enrollees, beginning plan year 2021. A proposal in the Administration’s FY 2020 budget would also eliminate cost sharing for generic drugs for Part D LIS enrollees, including for preferred multisource drugs and biosimilars, beginning in 2020. A similar proposal was recently introduced in Congress by Representative Joe Cunningham (D-SC1), and MedPAC recommended a similar change in 2016.

Budget Effects

For FY 2020, CBO estimates that eliminating cost sharing for generic drugs would increase federal spending by $23 billion over 10 years. By contrast, the Trump Administration estimates this proposal would reduce federal spending by $930 million over 10 years. CBO’s estimate suggests that higher spending could result from reducing LIS cost sharing for generic drugs, including for relatively expensive biosimilars, which could, in turn, lead to higher utilization of these drugs and, as a result, higher Medicare payments to plans on behalf of LIS enrollees. However, the Administration’s estimate suggests that eliminating cost sharing for generics and biosimilars may cause LIS enrollees to substitute generics for brands, which would reduce the amount of Medicare cost-sharing subsidies for LIS enrollees.

There is no CBO score yet available for eliminating cost sharing for generics as part of H.R. 3.

Effects on Beneficiaries

Eliminating cost sharing for generic drugs for LIS enrollees would create a stronger financial incentive to use generics, and would reduce out-of-pocket costs for LIS enrollees who take generic drugs and for those who are able to switch from brands to generics. Eliminating cost sharing would also ensure better access to needed drugs and less prescription abandonment. At the same time, unnecessary use of certain medications may increase due to the elimination of cost sharing.

expand Eligibility for Low-Income Subsidies

Beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid automatically receive Part D Low-Income Subsidies. However, the rate of LIS take-up by eligible beneficiaries who are not automatically enrolled has historically been low, causing concern with regard to low-income beneficiaries who may not enroll due to eligibility requirements or application difficulties.30

H.R. 3 includes a provision to institute automatic enrollment into the LIS program for all adults who reach age 65 and have incomes up to 200 percent of poverty who are enrolled in Medicaid. Furthermore, the proposal would broaden LIS eligibility requirements for low-income Part D enrollees by eliminating the asset test by increasing the income eligibility thresholds. Part D enrollees with incomes up to 200 percent FPL would be eligible for partial subsidies and enrollees with incomes up to 150 percent FPL would be eligible for full subsidies beginning for plan year 2022.31 A similar Congressional proposal introduced by Senator Bob Casey (D-PA) would also broaden LIS eligibility requirements for low-income Part D enrollees by eliminating the asset test and by extending full LIS benefits to Part D enrollees with incomes up to 200 percent.32 Neither the Trump Administration nor the Senate Finance Committee have proposed expanding eligibility for low-income subsidies.

Budget Effects

CBO has not scored these proposals.

Effects on Beneficiaries

Establishing automatic enrollment, expanding eligibility for full and partial subsidies under the LIS program and eliminating the asset test would increase the number of low-income people on Medicare who qualify for premium and cost-sharing assistance under Part D, and lower out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries who currently qualify for partial subsidies. Instituting automatic enrollment would reduce the government’s administrative burden for documenting eligibility, and eliminating the asset test would help more low-income beneficiaries qualify for LIS benefits. Furthermore, an increase in the number of people who qualify for premium and cost-sharing assistance may lead to higher drug utilization and increased medication adherence, due to lower out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries.

Recent Changes

Allow Medicare Advantage Plans to Require Step Therapy for Part B Drugs

Under CMS guidance in effect until August 2018, Medicare Advantage plans were not authorized to use utilization management tools such as step therapy for Part B drugs, unless these tools were allowed under traditional Medicare. CMS rescinded this guidance in August 2018. CMS recently finalized regulations that allow Medicare Advantage plans to use utilization management tools such as step therapy and prior authorization for Part B drugs, subject to certain rules.

According to CMS, these tools will enable Medicare Advantage plans to better manage and negotiate the price of Part B drugs, which will bring down costs for the Medicare program and beneficiaries. Certain safeguards would be established, such as changing the determination and appeals time frame to align with Part D rules; requiring Medicare Advantage plans to use Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees to review and approve step therapy, similar to Part D; including disclosure requirements in plan documents; and instituting policies and procedures to inform various stakeholders about the requirements. The new step therapy rules will apply only to new prescriptions rather than existing prescriptions for Part B enrollees. Most rules will be in effect beginning January 1, 2020 (though some amendments will take effect starting January 1, 2021), but the guidance applies to plan year 2019.

Budget Effects

According to the Administration’s estimates, Medicare will see a net savings of $1.9 billion over 10 years (2020-2029), which consists of gross savings of $1.91 billion and gross costs of $11.2 million due to increased beneficiary appeals. The Administration calculates that the use of step therapy will yield savings of 1.6 percent on Part B drugs due to increased use of less costly biosimilars, which are clinically equivalent to biologics, and will generate more favorable rebates for drugs with adequate competition. This proposal has not been scored by CBO.

Effects on Beneficiaries

According to the Administration’s estimates, Medicare beneficiaries will save $62 million under this proposal. Broader use of utilization management tools could lead to lower out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Advantage enrollees who take Part B drugs, if beneficiaries are able to substitute lower-cost medications for more costly ones. However, this proposal could also create barriers to medication access and could lead to administrative hassles. Step therapy and prior authorization could be burdensome for beneficiaries who may first have to try a number of drugs before they can take the one that is most effective for them, which could lead to preventable side effects, as well as poorer health outcomes due to delays in receiving optimal treatment. Furthermore, step therapy could lead to increased coverage appeals by beneficiaries who disagree with plan coverage decisions, and may lead to access issues for patients who are ultimately denied coverage for specific drugs. In response to these and other concerns, the Administration pointed to safeguards included in the final rule, which the Administration contends are adequate to ensure that these policies do not impede needed access to care.

Modify Coverage Requirements for Drugs in Part D Protected Classes

Under current program regulations, Part D plans are required to cover all or substantially all drugs in six protected classes (anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antineoplastics, antipsychotics, antiretrovirals, and immunosuppressants for the treatment of transplant rejection). Although the protected classes were originally created to smooth the transition from Medicaid to Medicare Part D for beneficiaries with these conditions when the latter program first started, the protected classes have been affirmed by Congress at various junctures since their launch in recognition of the unique challenges faced by beneficiaries diagnosed with the particular medical and mental health problems that protected class drugs are intended to treat.

While this policy has largely achieved its purpose, the Administration has suggested that the “essentially open coverage” of certain drug categories under the protected classes policy may lead to overutilization of these drugs and limit Part D plans’ ability to use tools that can bring down the costs of prescription drugs, including negotiating rebates. Currently, only 13 percent of protected class drugs have manufacturer rebates, according to one industry-funded analysis.33 Rebate information is proprietary and therefore drug-specific rebate data is not publicly available.

The Administration recently finalized a rule addressing coverage requirements for the protected classes. Under the final rule, the Administration codified an existing policy that allows for the broader use of prior authorization and step therapy for protected class drugs in five of the six protected classes (excluding antiretroviral medications) and in the case of new prescriptions only. The rule also gives plans greater authority to use utilization management tools, including indication-based formulary design, for drugs in five of the six protected classes. The rule did not finalize changes that would have allowed broader use of prior authorization and step therapy without distinguishing between new starts and existing therapies, as is currently permitted for other drug categories and classes. These changes will take effect on January 1, 2020.

The Administration proposed, but did not finalize, other changes that would have allowed plans to exclude some protected class drugs from their formularies under specific circumstances, including: 1) if the drug is a new formulation of a protected class drug, even if the older formulation is no longer on the market, or 2) if the price of a drug increases beyond the rate of inflation based on the CPI-U.

Budget Effects

The Administration did not project the net budget effect of changes included in the final rule.

Effects on Beneficiaries

Proponents in favor of coverage restrictions for protected class drugs contend that the proposal would have resulted in lower costs for patients, because plans could get greater discounts on covered drugs. However, in comments submitted in response to the proposed rule, patient advocates, pharmaceutical companies, and others expressed concern that the proposed changes would reduce patients’ access to needed medications, disrupt ongoing therapy, and create an unintended incentive for manufacturers to launch new drugs at higher prices. In response, the Administration modified the first provision on step therapy to apply to new prescriptions only, and did not finalize provisions that would have allowed some protected class drugs to be excluded from formularies. By codifying existing policy, Medicare beneficiaries who use protected class drugs will retain current access to these medications.

Require Part D Plan Sponsors to Use Real-Time Benefit Tools

Under the MMA, prescription drug plan sponsors are required to adopt Part D electronic prescribing (eRx) standards. However, there is no requirement that prescribers utilize eRx tools. Prescribers that choose to use these tools must comply with the National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP) SCRIPT standards, which allows prescribers to transmit information electronically, and the NCPDP Formulary and Benefits standards (F&B), which enable prescribers to view plan formularies. However, neither of these standards provides prescribers with real-time cost or coverage information for individual patients at the point of prescribing.

The Administration recently finalized a rule that would require Part D plan sponsors to adopt real-time benefit tools (RTBTs) that can be integrated with at least one prescriber’s eRx or electronic health record (EHR), to provide real-time, complete, and accurate patient-specific formulary and benefit information to prescribers. RTBTs could enable prescribers and patients together, at the point of prescribing, to determine the most suitable treatment based on clinical appropriateness, coverage, and cost. This rule requires plans to begin implementing RTBTs by January 1, 2021, though many plans have already implemented RTBTs voluntarily. There are also congressional proposals that establish more detailed requirements for the information to be included in this real-time benefit data, including a proposal in the Senate Finance Committee legislation.

Budget Effects

While there is no official budget estimate, the Administration states in the final rule that RTBTs will not be costly to implement, and that Medicare and beneficiaries will experience savings due to the use of lower-cost prescription drugs.

Effects on Beneficiaries

The Administration contends that the adoption of RTBTs will increase price and coverage transparency that will ultimately lower beneficiary out-of-pocket costs and improve medication adherence. Because RTBTs will enable prescribers to see beneficiary-specific Medicare Part D plan formularies and cost information at the point of prescribing, including formulary alternatives or utilization management data, prescribers and patients could collaborate to select a lower-cost treatment option. With research showing a positive association between higher patient cost sharing for medications and decreased medication adherence, RTBTs could also potentially lead to better medication adherence and better clinical outcomes for patients, according to the Administration. However, because there is no industry standard for RTBTs, it may be challenging to integrate these tools with various EHR or eRx systems, which could limit their efficacy. Furthermore, while successfully integrated RTBTs might give providers a real-time look at their patients’ Part D formularies, the lowest-cost treatment may not always be the optimal treatment option for a patient, suggesting that this tool’s impact may vary based on individual patient needs.

Conclusion

With drug prices on the rise and strong bipartisan public support for various policy approaches to lower drug costs, the Trump Administration and Congress have put forth a variety of proposals to address this issue, including several that would affect Medicare and beneficiary spending on prescription drugs. Many Democratic presidential candidates have also endorsed proposals to rein in drug spending. While there is interest among federal policymakers and candidates to restrain drug prices generally, there is particular interest in focusing on Medicare because of the wide range of policy levers available and the effect on the federal budget.

Under most of the proposals discussed in this brief, Medicare beneficiaries would likely see changes in their out-of-pocket costs, premiums, and access to medications, although the extent of these changes would vary depending on the proposal. These proposals would also have potentially wide-ranging effects on Medicare spending overall, which would depend greatly on the details specified in any final proposal and how stakeholders respond. Many of these proposals face strong opposition from the pharmaceutical industry, which has argued that proposals to reduce drug prices would adversely affect patients’ access to needed medications and dampen incentives for innovation by reducing revenue used to fund research and development. Furthermore, implementing some of these proposals in conjunction with others could produce interaction and spillover effects that may not be reflected in current estimates.

Going forward, it will be important to assess the implications and tradeoffs associated with each of these proposals on Medicare program spending, Medicare beneficiaries’ drug costs and coverage, and other stakeholders. While the prospects for these proposals are unclear, public concern over the affordability of prescription drugs suggests that the subject is unlikely to fade from the policy agenda in the near future.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures.We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

The authors acknowledge Jack Hoadley for his helpful comments on a draft of this paper.

Endnotes

- Nearly all Democratic presidential candidates have put forth plans to lower drug prices. See https://www.politico.com/2020-election/candidates-views-on-the-issues/health-care/drug-costs/; https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/policy-2020/medicare-for-all/ ↩︎

- Some examples of these proposals introduced in the 116th Congress are: H.R.987, “The Strengthening Health Care and Lowering Prescription Drug Costs Act,”, available at: https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr987/BILLS-116hr987rfs.pdf; S.1895, “The Lower Health Care Costs Act,” available at: https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/s1895/BILLS-116s1895rs.pdf; H.R. 2296, “The FAIR Pricing Act,” available at: https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr2296/BILLS-116hr2296ih.pdf ↩︎

- Senator Klobuchar is also a co-sponsor of S. 377, “Medicare Negotiation and Competitive Licensing Act”. ↩︎

- Ron Wyden (D-OR) has introduced a proposal that would eliminate cost sharing above the catastrophic threshold, but would fully implement this change in 2020 instead of a phased-in approach. See S.475, “The RxCap Act of 2019,” available at https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/s475/BILLS-116s475is.pdf ↩︎

- Members of the Ways and Means Committee have recommended a proposal that pairs an out-of-pocket limit with higher plan liability (and lower Medicare reinsurance) in the catastrophic phase. See https://waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/documents/ptD-drug-reinsur_01_xml.pdf ↩︎

- The Administration’s Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is also moving forward with a model that would modify reinsurance under Part D to create stronger incentives for plans to reduce costs. The model keeps the current catastrophic phase coverage allocation in the Medicare Part D benefit design (which cannot be modified without a change in law) with the same liability (5 percent for enrollees, 15 percent for plans, 80 percent for Medicare), but tests an approach where plans that choose to participate take on two-sided risk. Based on a plan’s federal reinsurance expenditures, CMS will make performance-based payments to plans that experience savings, but plans will also be subject to a penalty for any reinsurance spending above its target benchmark. The model is scheduled to begin January 2020. ↩︎

- The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) also recently proposed a restructured standard benefit design similar in nature to the Senate Finance Committee and House proposals, but without specifying threshold amounts or what share of liability each payer would bear for catastrophic costs. Under the current structure of the Part D benefit, brand manufacturers provide discounts in the coverage gap benefit phase of 70 percent, while beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs in the coverage gap benefit phase are 25 percent, and plans’ share is 5 percent. The MedPAC approach proposes eliminating the coverage gap benefit phase altogether and applying the manufacturer discount to the catastrophic phase, also called a “cap discount”. The American Action Forum also has a proposal that would change plan liability in the catastrophic phase, including increasing liability for plans and manufacturers during this phase: https://www.americanactionforum.org/print/?url=https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/redesigning-medicare-part-d-realign-incentives-1/ ↩︎