Management and Delivery of the Medicaid Pharmacy Benefit

Issue Brief

Managing the Medicaid prescription drug benefit and pharmacy expenditures is a perennial policy priority for state Medicaid programs. Though Medicaid prescription drug spending growth has slowed in recent years, similar to the overall US trend, state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending growth. Since the structure of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program means that state Medicaid programs essentially must cover all drugs, states cannot limit the scope of drugs covered in an effort to control drug costs. Instead, states have typically used an array of utilization controls to manage utilization of prescription drugs. The administration of the pharmacy benefit has evolved over time to include delivery through managed care and more reliance on pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). However, as costs continue to grow, the use of managed care and PBMs has expanded, and new “blockbuster” drugs come to market, states face new challenges in managing pharmacy benefits. This brief explores key questions about state management and delivery of Medicaid pharmacy benefits, including:

- What tools have states traditionally used to manage drug utilization in Medicaid?

- How has the administration of the pharmacy benefit evolved over time?

- What are current policy debates and proposals about Medicaid pharmacy management?

What tools have states traditionally used to manage drug utilization in Medicaid?

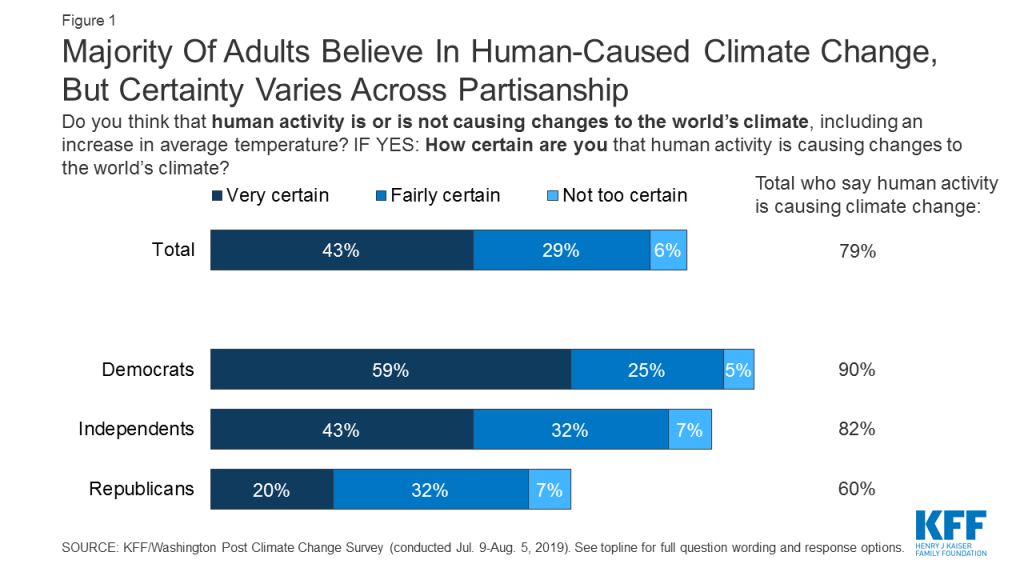

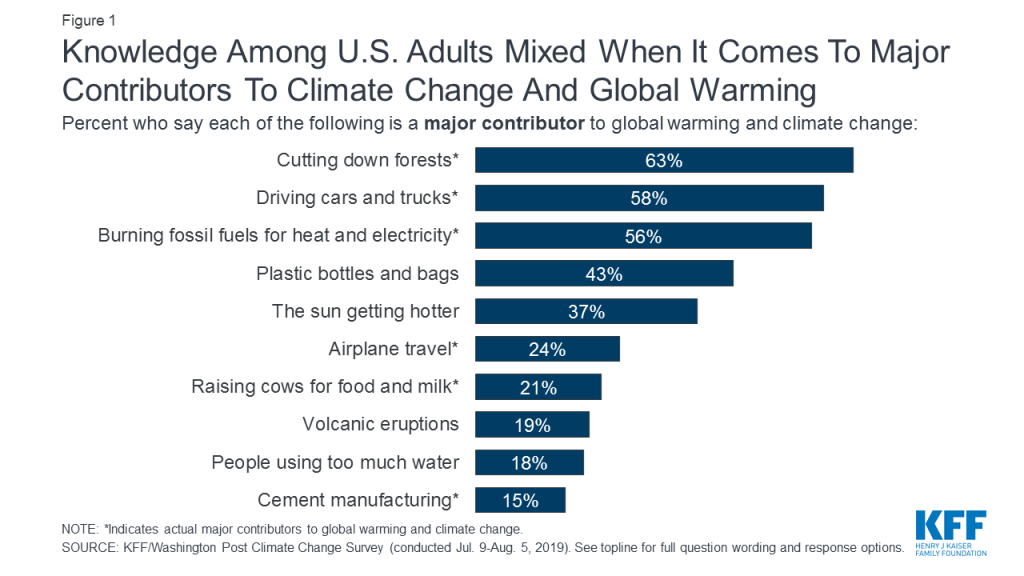

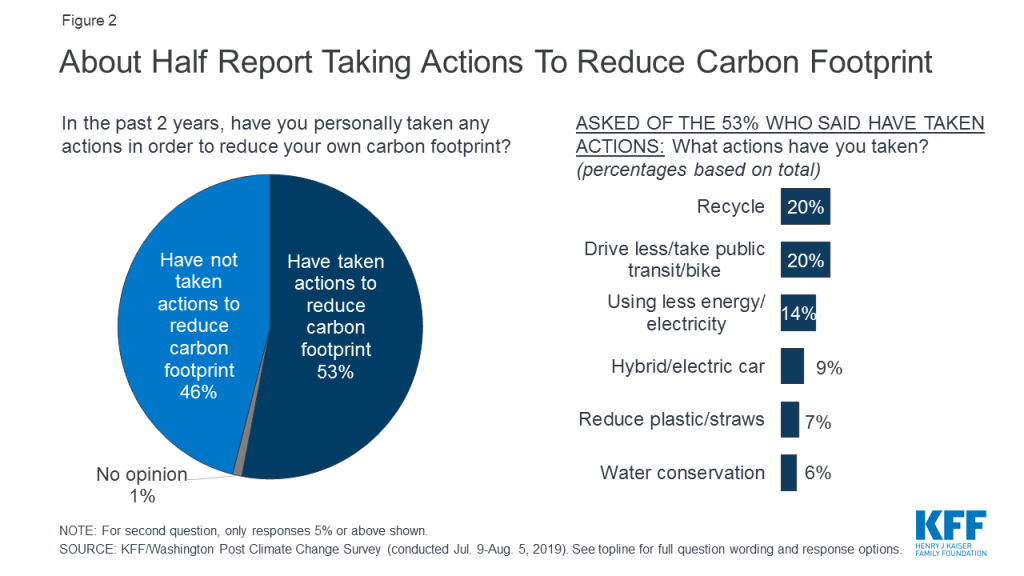

Most states use an array of measures to control utilization of prescription drugs in Medicaid. Under federal rules regarding the federal rebate agreement and medical necessity requirements, states have flexibility in administering their Medicaid prescription drug programs. As pharmacy expenditure growth became a greater Medicaid budget concern in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, most states implemented pharmacy cost containment strategies, including preferred drug lists (PDLs), supplemental rebate programs, state maximum allowable cost programs, multi-state purchasing pools, and prior authorization policies linked to clinical criteria. Prescription drug costs continue to be an area of concern for states, though growth has slowed from a peak in 2014 (Figure 1). States continue to routinely update and refine their drug utilization controls to respond to changes, especially new product offerings, in the pharmaceutical marketplace. In addition, states may implement prescription limits or impose beneficiary cost-sharing for certain groups to control prescription drug utilization.1 ,2

Preferred Drug Lists

Most state Medicaid programs maintain a preferred drug list (PDL) of outpatient prescription drugs, which is a list of outpatient drugs states encourage providers to prescribe over others. At least 45 states use PDLs in their fee-for-service (FFS) drug programs.3 ,4 A state may require prior authorization for a drug not on a preferred drug list or attach a higher co-pay, creating incentives for a provider to prescribe a drug on the PDL when possible. Since states are required to make available nearly all prescribed drugs from manufacturers with a national rebate agreement in both managed care and fee-for-service settings, PDLs allow states to manage utilization. In addition, PDLs often include drugs which are lower-cost or for which a manufacturer has provided supplemental rebates, as PDL placement is a primary lever that states use to negotiate supplemental rebate agreements.

Prior Authorization

One of the primary tools state have long used to manage the utilization of drugs is prior authorization. Prior authorization requires prescribers to obtain approval from the state Medicaid agency (or its contractor) before a particular drug can be dispensed.5 Goals of prior authorization include encouraging patient adherence, ensuring appropriate utilization, and discouraging waste.6 Prior authorization processes for covered outpatient drugs must meet two federal requirements: 1) they must respond to requests for authorization within 24 hours; and, 2) they must make available a 72-hour supply of medications in an emergency situation. Medicaid managed care plans’ prior authorization procedures must meet the same criteria.7 All states use prior authorization in FFS drug programs and at least 30 states apply the same prescription criteria to FFS and managed care for one or more drugs.8 ,9

States may require prior authorization for any drug covered by Medicaid but often do so for high-cost specialty drugs or non-preferred drugs. Prescriptions for non-preferred drugs (i.e., those not on the PDL) often require prior authorization. States may also require prior authorization for newly approved therapies while they examine the drug’s effectiveness and safety.

Drug Utilization Review (DUR)

States are required by federal law to have a drug utilization review (DUR) program in place to help ensure appropriate drug use.10 Drug utilization review programs must establish standards to ensure prescriptions are appropriate, medically necessary, and unlikely to lead to adverse medical results. DUR programs must also include evaluation for problems like duplicate prescriptions, incorrect dosage, and clinical misuse.11

DUR is a two-step process conducted by state Medicaid agencies, consisting of both prospective and retrospective drug utilization review. In prospective DUR, state Medicaid agencies employ electronic monitoring systems to screen prescription drug claims for concerns like duplicate prescriptions, incorrect dosage or duration of treatment, contraindications, and clinical misuse or abuse. Retrospective DUR is ongoing and involves periodic examination of claims data to identify patterns of fraud, abuse, underutilization, and medically unnecessary care.12 States are required to establish a DUR board to create the standards for appropriate drug use and to conduct retrospective drug utilization review. The board membership must consist of at least two-thirds physicians and pharmacists.13

Federal law requires states to make an annual DUR report on their Medicaid prescribing patterns, cost-savings associated with DUR, board activities and program operations. According to CMS, states saved an average of $57 million in 2017 through prospective DUR, and $1.46 million through retrospective review.14 However, due to heterogeneity in the methodologies used by states to calculate savings, comparisons of program cost-savings between states are unreliable.15

Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) Committees

To establish a PDL, federal law requires a state Medicaid agency to establish a committee of physicians and pharmacists to inform the development of the PDL, review drugs, and develop coverage decisions. 16 In many, but not all, states, these activities are performed by a pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee. In general, P&T committees are responsible for reviewing information on drug effectiveness and issuing evidence-based recommendations on coverage criteria, such as placement of drugs on the PDL and utilization controls. In addition to effectiveness and safety, the committee may also factor in price considerations to their decisions. P&T committees also may utilize contractors to assist in reviewing evidence, usually the state’s PBM or an academic institution in the state. States also have the option under federal law to use their drug utilization review board to fill this role.17

Since there are few federal requirements for P&T committees, the composition, structure, and operations of P&T committees may vary from state to state. Federal requirements for committee composition specify pharmacists, physicians and other “appropriate” individuals, but otherwise leave states with flexibility for determining committee operations.18 Meeting frequency and procedures can vary between P&T committees. Under federal Medicaid rebate rules, states are required to cover all drugs from a manufacturer that has a rebate agreement in place once they are approved by the FDA and enter the market. This requirement means states must quickly decide how to categorize the drug and if it will be on the PDL.19 States often require prior authorization of a new drug before it is reviewed by the P&T committee and clinical guidelines are developed. The length for the evaluation of a drug and development of coverage criteria is typically one to three months but can be as long as one year.20 It often takes longer for committees to review breakthrough or first-in-class drugs and therapies than for a new formulation of a drug or a new drug in an existing class.

Cost-sharing and Prescription Limits

States have the authority to implement cost-sharing to control utilization and costs of prescription drugs. For example, states may implement different co-payments for drugs on a preferred drug list or generic drugs, compared to non-preferred or brand drugs. Most states now utilize some measure of cost-sharing in their Medicaid pharmacy benefit. In fiscal year (FY) 2018, 35 states and DC reported having co-payments for prescription drugs in place for Medicaid non-exempt beneficiaries.21 Co-payments are statutorily capped at $4 for preferred drugs. For non-preferred drugs, states may require co-pays up to $8 for most beneficiaries with income at or below 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL).22

In addition to implementing cost-sharing, states may limit the number of prescriptions a beneficiary may access without prior authorization. These restrictions may include a limit on the total number of prescriptions per month or a limit on the number of brand drugs. Medicaid programs allow prescribers and pharmacists to submit prior authorization requests to override these limits when medically necessary or under other specific circumstances, subject to federal requirements for prior authorization processes. In addition, states are authorized under federal law to set minimum or maximum numbers of pills or doses per prescription as well as the number of refills.23 In order to implement prescription coverage restrictions that are not expressly permitted by federal statute,24 states need waiver authority from CMS. For example, Tennessee implemented a prescription coverage limit of five prescriptions per month for adult beneficiaries not in long-term care in its TennCare demonstration.25 However, the state exempts many medications from the prescription limit and allows prescribers to submit exception requests for beneficiaries.26

How has the administration of the pharmacy benefit evolved over time?

States continue to use pharmacy utilization management strategies in Medicaid, but because most states have adopted most of these strategies, activity is generally around refining them. However, such actions have slowed in recent years as states reach the limits of utilization controls allowed under federal law. The rise in prevalence of managed care in Medicaid and in pharmacy benefits has also led to changes in how states manage their benefits.

Capitated managed care is now the dominant way in which states deliver services, including prescription drugs, to Medicaid beneficiaries. States pay managed care organizations (MCOs) a monthly fee (capitation rate) to cover the cost of services provided to beneficiaries and any administrative expenses. Thirty-three of the 40 states with comprehensive risk-based managed care enroll at least 75% of their Medicaid beneficiaries in MCOs.27 As more states have enrolled additional Medicaid populations into managed care arrangements over time and included pharmacy benefits in managed care contracts, MCOs have played an increasingly significant role in administering the Medicaid pharmacy benefit. Although MCOs provide comprehensive services to beneficiaries, states may carve specific benefits, including the pharmacy benefit, out of MCO contracts to FFS systems.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended federal statutory rebates to prescription drugs provided under Medicaid managed care arrangements, and most states now “carve in” prescription drugs. Prior to the ACA, manufacturers only had to pay rebates for outpatient drugs purchased on a fee-for-service basis, not those purchased through managed care. This practice encouraged states to “carve out” prescription drugs to obtain rebates. In FY 2011, 21 states reported having full or partial carve-outs of prescription drugs.28 Extending rebates to drugs purchased through managed care has resulted in more states carving drug coverage back into managed care. Of the 40 states contracting with comprehensive risk-based MCOs in 2018, 35 states reported that the pharmacy benefit was carved in, with some states reporting exceptions such as high-cost or specialty drugs.29

States are increasingly implementing uniform requirements30 across their pharmacy programs, including uniform PDLs and uniform clinical protocols, which are state-prescribed requirements for drug utilization that apply across FFS and MCOs.31 These uniform requirements can give the state more leverage in negotiations with manufacturers for supplemental rebates. Uniform requirements can also ensure that MCOs follow state rules and comply with how states want the program administered even when prescription drugs are carved in. Nearly all states use prior authorization and PDLs in FFS programs. In 2018, 14 states reported having in place a uniform PDL for at least one drug class, with three states indicating plans to implement a uniform PDL in FY 201932 and four states indicating plans to implement in FY 2020.33 Uniform clinical protocols are more common, with 30 states reporting them in place in FY 2018.34

In conjunction, states are also increasingly utilizing PBMs in their Medicaid prescription drug programs to help administer the pharmacy benefit. While the relationship between state Medicaid programs and PBMs is not new, the extent to which states rely on PBMs has grown significantly in the past ten years. While states once primarily contracted with PBMs for administrative support, like claims processing, states are now also using PBMs to negotiate supplemental rebates and conduct clinical drug class reviews that inform PDL decision-making, largely due to resource limitations.35

PBMs perform a variety of financial and clinical services for Medicaid programs, including adjudicating claims, administering rebates, monitoring utilization, supporting DUR processes, and overseeing and formulating preferred drug lists.36 States may utilize PBMs in both managed care and fee-for-service settings but payment rules differ for prescription drugs purchased through FFS and MCOs. Those purchased through MCOs have fewer restrictions and regulations on the prices paid to pharmacies. Federal rules state that MCOs must set payment rates sufficient to guarantee beneficiary access, but are not bound by rules regarding ingredient costs like drugs purchased through FFS.37 PBMs acting on behalf of managed care companies negotiate individual prices with pharmacies and can set PDLs and proprietary maximum allowable costs (MACs).38

What are key policy issues in management of the Medicaid pharmacy benefit?

PBM Regulation, Transparency, and Spread Pricing

The financial responsibilities PBMs take on, including negotiating prescription drug rebates with manufacturers and dispensing fees with pharmacies, have generated considerable policy debate about price transparency and spread pricing. Spread pricing refers to the difference between the payment the PBM receives from the MCO and the reimbursement amount it pays to the pharmacy.39 Lack of transparency and regulations have allowed PBMs to keep this “spread” as profit.

States are beginning to question whether use of PBMs produces savings or generates additional costs. While states turned to these arrangements to limit their financial exposure, recent evidence indicates that they may increase costs overall. In 2018, a report by Ohio’s state auditor found that PBMs cost the state program nearly $225 million through spread pricing in managed care.40 Similar analysis by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission found that PBMs charged MassHealth MCOs more than the acquisition price for generic drugs in 95% of the analyzed pharmaceuticals in the last quarter of 2018.41 Michigan found that PBMs had collected spread of more than 30% on generic drugs and a report found that the state had been overcharged $64 million.42 Other states have released similar reports finding high amounts of spread on generic prescriptions.43 Concerns about Medicaid spread pricing led CMS to issue guidance in May 2019 on how managed care plans should report spread pricing in order to more accurately calculate plans’ medical loss ratios (MLRs).44

Some states are reassessing their use of PBMs and turning to a variety of policies to limit spread pricing, like licensure requirements, reporting requirements, and increased oversight. For example, after the 2018 report, Ohio prohibited its managed care plans from contracting with PBMs that use spread pricing.45 Since then, the state has announced it will move to contract with a single PBM for its entire managed care program starting July 2020, with enhanced transparency reporting requirements.46 Michigan is planning to no longer use PBMs and to use FFS to pay for its prescription drugs.47 Other states like Nevada have implemented policies establishing PBMs as fiduciaries with a duty to act in the best interest of pharmacies and beneficiaries.48 A similar proposal that passed both chambers of government in New York requires PBMs to act primarily in the interest of covered individuals and health plans, in addition to transparency reporting requirements.49 Federal legislative proposals would prohibit spread pricing by PBMs in Medicaid managed care.50

P&T and DUR Variation and Conflict of Interest

Variation in P&T committees and DUR procedures across the states has led to recent policy proposals for federal standards in these procedures.51 Advocates of federal standards argue that establishing a period for public comment on decisions, setting a minimum meeting frequency, and other such measures relating to P&T committee operations can ensure transparency for all Medicaid beneficiaries and aid comparison between states. Similarly, proposals have also suggested standardizing the methodology for calculating cost-savings in the DUR program.52 Some have raised concerns about discrepancies between DUR requirements for Medicaid managed care plans and fee-for-service. Though managed care plans that perform their own prospective and retrospective DUR activities must meet the same federal requirements as fee-for-service programs, only four states required plans to use the same criteria as fee-for-service in 2017.53

Conflict-of-interest policies for members of the P&T board are also not standardized by statute, leading to recent state and federal proposals requiring conflict-of-interest policies for P&T committees and DUR boards.54 Recent investigations into the influence of pharmaceutical companies on the Medicaid drug review process have called more attention to the limits of conflict-of-interest policies for P&T committees.55 After a 2018 investigation by NPR and the Center for Public Integrity revealed that some P&T committee members were receiving inappropriate financial remuneration from drug manufacturers, ostensibly in exchange for coverage decisions,56 some states introduced bills to address industry influence and financial disclosures in state P&T committees.57 ,58 Legislation recently introduced in the Senate would also place conflict-of-interest requirements on P&T committees & DUR Boards.59

Access to New, Breakthrough Drugs

The cost burden of high-cost and specialty drugs makes new and first-in-class drugs a pressing policy area for Medicaid agencies. Since Medicaid must cover nearly all drugs, the introduction of new drugs can be particularly challenging for programs in the initial phases of coverage. This challenge was particularly acute with the introduction of costly direct acting antivirals (DAAs) to treat hepatitis C in 2013. In order to manage their Medicaid budgets, states created narrow coverage criteria and implemented prior authorization restrictions.60 In addition to restrictions based on clinical need, some states also required that a patient meet with a specialist, as well as drug counseling, drug testing, and periods of abstinence from drugs and alcohol. However, these restrictions were inconsistent with treatment recommendations and with federal law,61 and federal class action suits led states to loosen restrictions on DAAs. 62 In addition, although states have placed particular focus on DAAs, they remain vigilant about other high cost drugs as well, such as hemophilia, oncology, and diabetes classes of drugs.

States are taking a variety of approaches to balancing beneficiary access to pharmacy benefits and spending for “blockbuster” drugs. Notably, Louisiana’s recently implemented modified subscription model, or “Netflix” model, allows the state to increase beneficiary access to hepatitis C drugs while capping gross spending.63 The five-year supplemental rebate agreement between the state and manufacturer sets a capped expenditure amount, beyond which the state will continue to receive drugs at no additional cost.64 Idaho actively manages specialty drugs following the introductory phase by conducting manual prior authorization of all claims for the first six months a new drug is available.65 Other states limit the ability of Medicaid agencies to place utilization controls on certain classes of drugs, like hepatitis C drugs, hemophilia factor, and HIV antiretrovirals. Federal proposals include having CMS work more closely with states to proactively monitor state compliance with drug coverage requirements for new specialty drugs66 or creating a drug coverage grace period after the introduction of new drugs that would provide states with more time to review scientific literature and establish appropriate coverage criteria.67

Closed Formularies

There is some limited federal and state interest in moving Medicaid benefits management beyond PDLs and PA to having a closed formulary, but such efforts face legal and administrative challenges. The structure of the federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program essentially creates an open formulary in Medicaid. This approach stands in contrast to a closed formulary, under which only specific drugs in each therapeutic class are covered. A small number of states have sought waiver authority for a closed formulary in Medicaid. In 2017, Massachusetts submitted an application to CMS that included a provision to amend its Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waiver to create a closed formulary.68 Their proposal was rejected by CMS because the state proposed to continue collecting rebates through the MDRP while excluding drugs from coverage.69 In November 2019, Tennessee submitted to CMS a Section 1115 waiver request that includes a proposal similar to that of Massachusetts. The waiver proposes a “commercial-style closed formulary” but does not specify whether the state is proposing to opt out of the statutory rebate program. The proposal is pending a decision from CMS at the time of this writing.70 The Trump administration has also expressed interest in closed formularies in Medicaid through a proposed new Medicaid demonstration authority to enable up to five state Medicaid programs to create their own formularies and negotiate directly with manufacturers instead of participating in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. Currently no states are participating in the demonstration.

Summary

Budget and fiscal challenges are a top priority of Medicaid programs, including managing and responding to high cost prescription drugs and managing pharmacy expenditures. States are limited in their leverage when it comes to controlling drug spending and use a variety of strategies to manage utilization. States continue to update their management tools over time, including an increased reliance on managed care and PBMs. As policymakers debate proposals that include provisions related to Medicaid pharmacy benefits, it is important to understand the challenges state Medicaid programs face and how policy proposals may impact Medicaid beneficiaries and costs.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Endnotes

- For individuals with incomes above 150% of the FPL, rules allow states to establish higher cost-sharing, including coinsurance of up to 20% of the cost of the drug, for non-preferred drugs. See 78 Federal Register 42159-42322 (July 15, 2013), and Laura Snyder and Robin Rudowitz, Premiums and Cost-sharing in Medicaid (Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2013), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/premiums-and-cost-sharing-in-medicaid-a-review-of-research-findings/. ↩︎

- State Health Facts, “Medicaid Benefits: Prescription Drugs, 2018,” KFF, https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/prescription-drugs. ↩︎

- Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Barbara Coulter Edwards, Aimee Lashbrook, Elizabeth Hinton, Larisa Antonisse, and Robin Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 (KFF, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/. ↩︎

- As of 2015, 45 states reported using a PDL, and none have reported removing it in subsequent years. See Vernon Smith, Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Robin Rudowitz, Laura Snyder, and Elizabeth Hinton, Medicaid Reforms to Expand Coverage, Control Costs and Improve Care: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2015 and 2016 (KFF, October 2015), http://files.kff.org/attachment/report-medicaid-reforms-to-expand-coverage-control-costs-and-improve-care-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2015-and-2016. ↩︎

- Jane Tilly and Linda Elam, Prior Authorization for Medicaid Prescription Drugs in Five States: Lessons for Policy Makers (KFF, April 2003), http://files.kff.org/attachment/report-prior-authorization-for-medicaid-prescription-drugs-in. ↩︎

- N. Pinson, A. Thielke, V. King, J. Beyer, and R. Driver, Medicaid and Specialty Drugs: Current Policy Options (Center for Evidence-based Policy, Oregon Health & Science University), http://centerforevidencebasedpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/MED_Medicaid_and_Specialty_Drugs_Current_Policy_Options_Final_Sept-9-2016.pdf ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8 (d) (5) ↩︎

- Gifford, Ellis, Edwards, Lashbrook, Hinton, Antonisse, and Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 (KFF, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/. ↩︎

- Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Aimee Lashbrook, Mike Nardone, Elizabeth Hinton, Robin Rudowitz, Maria Diaz, and Marina Tian, A View from the States: Key Medicaid Policy Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020 (KFF, October 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/a-view-from-the-states-key-medicaid-policy-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2019-and-2020/. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. §1396r-8 (g) ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. §1396r-8 (g) ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Drug Utilization Review,” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/drug-utilization-review/index.html. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. §1396r-8 (g) (3) ↩︎

- CMS, “Drug Utilization Review,” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/drug-utilization-review/index.html. ↩︎

- Sergio Prada and Johan Loaiza, “Comparing the Medicaid Prospective Drug Utilization Review Program Cost-Savings Methods Used by State Agencies in 2015 and 2016,” American Health & Drug Benefits 12, no. 1 (February 2019): 7-12, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6404806/. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. §1396r-8 (d) (4) ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. §1396r-8 (d) (4) (A) ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. §1396r-8 (d) (4) ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, Next Steps in Improving Medicaid Prescription Drug Policy (MACPAC, June 2019), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Next-Steps-in-Improving-Medicaid-Prescription-Drug-Policy.pdf. ↩︎

- MACPAC, Next Steps in Improving Medicaid Prescription Drug Policy (MACPAC, June 2019), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Next-Steps-in-Improving-Medicaid-Prescription-Drug-Policy.pdf. ↩︎

- State Health Facts, “Medicaid Benefits: Prescription Drugs, 2018,” KFF, https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/prescription-drugs. ↩︎

- States may also charge up to 20% of the amount Medicaid pays for people with income above 150% FPL. See MACPAC, “Cost sharing and premiums,” https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/cost-sharing-and-premiums/. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. §1396r-8 (d) (6) ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. §1396r-8 (d) (1) ↩︎

- CMS, TennCare II Section 1115 Demonstration Fact Sheet (CMS, February 2016), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/tn/tn-tenncare-ii-fs.pdf. ↩︎

- Division of TennCare, “Pharmacy,” https://www.tn.gov/tenncare/members-applicants/pharmacy.html. ↩︎

- Gifford, Ellis, Lashbrook, Nardone, Hinton, Rudowitz, Diaz, and Tian, A View from the States: Key Medicaid Policy Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020 (KFF, October 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/a-view-from-the-states-key-medicaid-policy-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2019-and-2020/. ↩︎

- Vernon Smith, Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Robin Rudowitz, and Laura Snyder, Moving Ahead Amid Fiscal Challenges: A Look at Medicaid Spending, Coverage and Policy Trends: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2011 and 2012 (KFF, October 2011), https://modern.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/8248.pdf. ↩︎

- Gifford, Ellis, Edwards, Lashbrook, Hinton, Antonisse, and Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 (KFF, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/. ↩︎

- Gifford, Ellis, Edwards, Lashbrook, Hinton, Antonisse, and Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 (KFF, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/. ↩︎

- Uniform PDL requirements are state-prescribed requirements for designating a specific drug product as preferred or non-preferred. Uniform clinical protocols are state-prescribed medical necessity criteria for a specific drug product. ↩︎

- Gifford, Ellis, Edwards, Lashbrook, Hinton, Antonisse, and Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 (KFF, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/. ↩︎

- Gifford, Ellis, Lashbrook, Nardone, Hinton, Rudowitz, Diaz, and Tian, A View from the States: Key Medicaid Policy Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020 (KFF, October 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/a-view-from-the-states-key-medicaid-policy-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2019-and-2020/. ↩︎

- Gifford, Ellis, Edwards, Lashbrook, Hinton, Antonisse, and Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 (KFF, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/. ↩︎

- Jenny Gaffney, Marielle Kress, Caroline Pearson, Tanisha Carino, John Connolly, and Robin Rudowitz, The Role of Clinical and Cost Information in Medicaid Pharmacy Benefit Decisions: Experience in Seven States (KFF, September 2011), https://modern.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/8233.pdf. ↩︎

- States that use PBMs in administering the prescription drug benefit in a fee-for-service setting pay the PBM administrative fees for these services. See Magellan Health, Medicaid Pharmacy Trend Report, Second Edition (Magellan Rx Management, 2017), https://www1.magellanrx.com/media/671872/2017-mrx-medicaid-pharmacy-trend-report.pdf. See also https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Drug-Brief1.pdf. ↩︎

- 81 Federal Register 5169-5357, (February 1, 2016). ↩︎

- MACPAC, Medicaid Payment for Outpatient Prescription Drugs (MACPAC, May 2018), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Medicaid-Payment-for-Outpatient-Prescription-Drugs.pdf. ↩︎

- Sarah Lanford and Maureen Hensley-Quinn, New PBM Laws Reflect States’ Targeted Approaches to Curb Prescription Drug Costs (National Academy for State Health Policy, August 2019), https://nashp.org/new-pbm-laws-reflect-states-targeted-approaches-to-curb-prescription-drug-costs/. ↩︎

- Ohio Auditor of State, Ohio’s Medicaid Managed Care Pharmacy Services (Ohio Auditor of State, August 2018), https://audits.ohioauditor.gov/Reports/AuditReports/2018/Medicaid_Pharmacy_Services_2018_Franklin.pdf. ↩︎

- Massachusetts Health Policy Commission, “Cracking Open the Black Box of Pharmacy Benefit Managers: PBM Pricing for Generic Drugs in Massachusetts Medicaid Programs and the Commercial Market,” HPC Datapoints 12 (June 2019): 1-8, https://www.mass.gov/doc/datapoints-issue-12-printable-version/download. ↩︎

- Michigan similarly found that PBMs had collected spread of more than 30% on generic drugs and a report found that the state had been overcharged $64 million. The state has since decided to no longer use PBMs and to use FFS to pay for its prescription drugs. See 3 Axis Advisors, Analysis of PBM Spread Pricing in Michigan Medicaid Managed Care (Michigan Pharmacists Association, April 2019), https://www.michiganpharmacists.org/Portals/0/resources/3AA%20MI%20Medicaid%20managed%20care%20analysis %20-%20Final%2004.10.19.pdf?ver=2019-04-30-064856-343&ver=2019-04-30-064856-343. ↩︎

- A report sponsored by Pharmacists Society of the State of New York found that in Q4 of 2017, the managed care PBM spread was 39% of the state’s overall generic spend, and that between 4/1/17 and 3/30/18, the spread was 24% of the overall generic spend. The report suggested that “managed care PBMs are pricing most generic drugs below a pharmacy’s cost to dispense and potentially using these savings to subsidize spread pricing on the remaining generic drugs.” A report prepared in response to Kentucky Senate Bill 5 found that PBMs in the state reported a spread of 12.9% ($123.5 million not paid to pharmacies and kept by the PBMs. See 3 Axis Advisors, Analysis of PBM Spread Pricing in New York Medicaid Managed Care (Pharmacists Society of the State of New York, January 2019), https://files.constantcontact.com/599cc597301/971bd1aa-2a80-464b-a85c-e3afaa8a577a.pdf; Office of Health Data Analytics, Medicaid Pharmacy Pricing: Opening the Black Box (Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, February 2019), https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/ohda/Documents1/CHFSMedicaidPharmacyPricing.pdf. ↩︎

- CMS, “CMS Issues New Guidance Addressing Spread Pricing in Medicaid, Ensures Pharmacy Benefit Managers are not Up-Charging Taxpayers,” CMS Newsroom (May 15, 2019), https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-issues-new-guidance-addressing-spread-pricing-medicaid-ensures-pharmacy-benefit-managers-are-not ↩︎

- Ohio Department of Medicaid, “Guidance for Managed Care Plans, August 14, 2018,” https://issuu.com/thecolumbusdispatch/docs/mco_pass_through_ltr_8.14.18. ↩︎

- Ohio H.B. 166, “Creates FY 2020-2021 operating budget,” 133rd General Assembly (2019), https://www.legislature.ohio.gov/legislation/legislation-summary?id=GA133-HB-166. ↩︎

- Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, “Proposed Policy Draft: Medicaid Health Plan Pharmacy Drug Coverage Transition,” https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/1936-Pharmacy-P_673863_7.pdf ↩︎

- Nevada S.B. 539, “Revises provisions relating to prescription drugs,” 79th Session (2017), https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/79th2017/Bill/5822/Overview. ↩︎

- New York A. 2836 / S. 6531, “An act to amend the public health law,” 2019-2020 Legislative Session (2019), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/a2836/amendment/a. ↩︎

- U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, Description of the Chairman’s Mark: The Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act (PDPRA) of 2019 (Senate Finance, July 2019), https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FINAL%20Description%20of%20the%20Chairman’s%20Mark %20for%20the%20Prescription%20Drug%20Pricing%20Reduction%20Act%20of%202019.pdf. ↩︎

- MACPAC, Next Steps in Improving Medicaid Prescription Drug Policy (MACPAC, June 2019), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Next-Steps-in-Improving-Medicaid-Prescription-Drug-Policy.pdf. ↩︎

- Prada and Loaiza, “Comparing the Medicaid Prospective Drug Utilization Review Program Cost-Savings Methods Used by State Agencies in 2015 and 2016,” American Health & Drug Benefits 12, no. 1 (February 2019): 7-12, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6404806/. ↩︎

- Edwin Park, How to Strengthen the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program to Address Rising Medicaid Prescription Costs (Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, January 2019), https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Medicaid-Rx-Policy-Options-v4.pdf. ↩︎

- Nicole Yvonne Nguyen and Lisa Bero, “Medicaid Drug Selection Committees and Inadequate Management of Conflicts of Interest,” JAMA Internal Medicine 173, no. 5 (March 2013): 338-343, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/1570087; and Nirav Shah, “Managing Potential Conflicts of Interest in State Medicaid Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committees: Seeking Harmony,” JAMA Internal Medicine 173, no. 5 (March 2013): 344, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/1570097. ↩︎

- Liz Essley Whyte, Alison Fitzgerald Kodjak, and Joe Yerardi, “How Drugmakers Sway States to Profit Off of Medicaid,” Center for Public Integrity (July 18, 2018), https://publicintegrity.org/state-politics/how-drugmakers-sway-states-to-profit-off-of-medicaid; and Brenna Goth, “Arizona Medicaid Committee Must Disclose Drug-Company Ties,” Bloomberg Law (July 30, 2018), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/arizona-medicaid-committee-must-disclose-drug-company-ties. ↩︎

- Whyte, Kodjak, and Yerardi, “How Drugmakers Sway States to Profit Off of Medicaid,” Center for Public Integrity (July 18, 2018), https://publicintegrity.org/state-politics/how-drugmakers-sway-states-to-profit-off-of-medicaid. ↩︎

- Edwin Park, “Senate Finance Committee Considers Bipartisan Bill to Lower Federal and State Medicaid Drug Costs,” Say Ahhh! Georgetown CCF (July 23, 2019), https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2019/07/23/senate-finance-committee-considers-bipartisan-bill-to-lower-federal-and-state-medicaid-drug-costs/; and Whyte, Kodjak, and Yerardi, “How Drugmakers Sway States to Profit Off of Medicaid,” Center for Public Integrity (July 18, 2018), https://publicintegrity.org/state-politics/how-drugmakers-sway-states-to-profit-off-of-medicaid. ↩︎

- Goth, “Arizona Medicaid Committee Must Disclose Drug-Company Ties,” Bloomberg Law (July 30, 2018), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/arizona-medicaid-committee-must-disclose-drug-company-ties; and Arizona E.O 2018-06, “Increasing Transparency and Eliminating Undue Influence by Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Companies,” (2018), https://azgovernor.gov/sites/default/files/executive_order_2018-06_0_0.pdf. ↩︎

- U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, Description of the Chairman’s Mark: The Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act (PDPRA) of 2019 (Senate Finance, July 2019), https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FINAL%20Description%20of%20the%20Chairman’s%20Mark %20for%20the%20Prescription%20Drug%20Pricing%20Reduction%20Act%20of%202019.pdf. ↩︎

- Soumitri Barua, Robert Greenwald, Jason Grebely, Gregory J. Dore, Tracy Swan, and Lynn E. Taylor, “Restrictions for Medicaid Reimbursement of Sofosbuvir for the Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the United States,” Annals of Internal Medicine 163, no. 3 (August 2015): 215-223, https://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/2362306/restrictions-medicaid-reimbursement-sofosbuvir-treatment-hepatitis-c-virus-infection-united. ↩︎

- CMS, “For State Technical Contacts: Assuring Medicaid Beneficiaries Access to Hepatitis C (HCV) Drugs,” (CMS, November 2015), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/prescription-drugs/downloads/rx-releases/state-releases/state-rel-172.pdf. ↩︎

- A settlement in April 2017 made this provision permanent. See N.C. and L.J. v. Washington State Health Care Authority, Public Employees Benefits Board, and Dorothy Teeter in her official capacity, N.A., Case No. 16-2-08002-2 SEA (King County Superior Court, 2016), https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/ump/Hep-C-settlement-agreement.pdf. ↩︎

- Division of Pharmacy, “Louisiana SPA #19-0018,” CMS, https://www.medicaid.gov/State-resource-center/Medicaid-State-Plan-Amendments/Downloads/LA/LA-19-0018.pdf. ↩︎

- For more on VBPs in supplemental rebates, see Rachel Dolan, Understanding the Medicaid Prescription Drug Rebate Program (KFF, November 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-medicaid-prescription-drug-rebate-program/ ↩︎

- Pinson, Thielke, King, Beyer, and Driver, Medicaid and Specialty Drugs: Current Policy Options (Center for Evidence-based Policy, Oregon Health & Science University), http://centerforevidencebasedpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/MED_Medicaid_and_Specialty_Drugs_Current_Policy_Options_Final_Sept-9-2016.pdf ↩︎

- MACPAC, Next Steps in Improving Medicaid Prescription Drug Policy (MACPAC, June 2019), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Next-Steps-in-Improving-Medicaid-Prescription-Drug-Policy.pdf. ↩︎

- MACPAC, Next Steps in Improving Medicaid Prescription Drug Policy (MACPAC, June 2019), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Next-Steps-in-Improving-Medicaid-Prescription-Drug-Policy.pdf. ↩︎

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts, “MassHealth Section 1115 Demonstration Amendment Request Submitted to CMS,” (September 8, 2017), https://www.mass.gov/doc/section-1115-demonstration-amendment-request-submitted-to-cms-1/download. ↩︎

- Virgil Dickson, “CMS denies Massachusetts’ request to choose which drugs Medicaid covers,” Modern Healthcare (June 27, 2018), https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180627/NEWS/180629925/cms-denies-massachusetts-request-to-choose-which-drugs-medicaid-covers ↩︎

- Division of TennCare, “TennCare II Demonstration: Amendment 42 Modified Block Grant and Accountability,” (November 20, 2019), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/tn/tn-tenncare-ii-pa10.pdf ↩︎