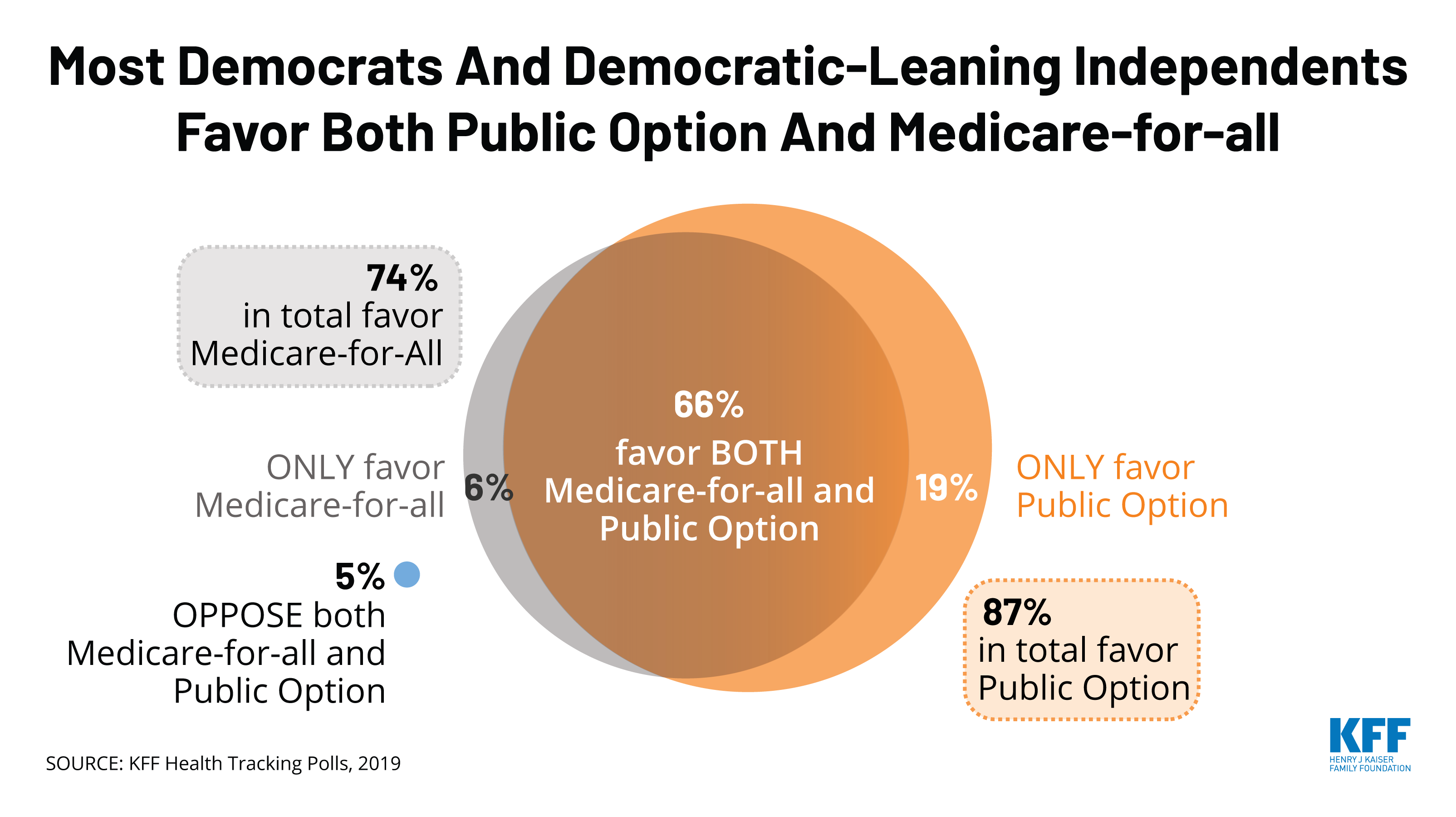

Several democratic presidential primary candidates and Members of Congress have proposed or endorsed a “public option” to expand health coverage and lower health care costs, giving people the choice between private insurance and a publicly-sponsored plan. The approaches of public option proposals differ from Medicare-for-all in that they expand upon, rather than replace, current sources of coverage (e.g., employer-sponsored plans, the marketplaces, Medicare, and Medicaid). Similar to Medicare-for-all, a public option could make broader use of Medicare-like provider payment rates, lowering the cost of coverage relative to private insurance. Recent polls find greater support for a public option than for Medicare-for-all.

Democratic candidates Biden, Buttigieg, Steyer, and Warren have each proposed a public option approach that aims to broaden coverage and make health care more affordable. Senator Warren describes her public option as an incremental measure before pushing for subsequent passage of separate Medicare-for-all legislation. Public option proposals vary in how many people would gain coverage, the number of people who shift from their current health plan to the public option, the potential size of the public option, the affordability of coverage, and changes in spending by the federal government and other payers. The impact on coverage and affordability would depend on factors such as eligibility criteria, the scope of covered benefits, the level of subsidies provided, and provider payment rates. See Table 1 for short descriptions of each proposal.

This issue brief presents a high-level view of key questions regarding current public option proposals supported by both presidential candidates and Members of Congress.

Background

As Congress debated the Affordable Care Act (ACA) ten years ago, some lawmakers supported a public option to address anticipated concerns about private insurer participation in new ACA marketplaces and the stability of private plan offerings, and to leverage greater competition to help lower costs and premiums in the marketplaces. The House-passed version of the ACA included a public option, offered only through the marketplace, which would cover the same benefits and be subject to the same standards as other marketplace plans. Ultimately, that provision was dropped from the final legislation when it was considered by the Senate.

Since then, some policymakers have continued to press for a public option. Congressional bills to establish a public option since 2017 have evolved and included other ACA enhancements. This year, presidential candidates have proposed public options that could be even more expansive, offering more Americans a choice between their current private-sector coverage and a public option. Some are described as a glide path or transition to Medicare-for-all.

The health insurance industry and many provider organizations have opposed a public option. Private insurers raise concerns that they would have difficulty competing on a level playing field with a public option, and ultimately would be put out of business. Hospitals and other health care providers raise concerns about the adequacy of payment rates in a public option and potential loss of revenues.

1. How would a public option differ from Medicare-for-all?

Unlike Medicare-for-all, a new public option would be offered as an option for eligible individuals rather than replacing current sources of coverage. Under most proposals, the public option would be administered by the federal government, as Medicare is today. An alternative approach would allow states to build a public option based on the Medicaid program.

Medicare-for-all proposals aim to achieve universal and cradle-to-grave coverage. In contrast, under a public option proposal, people could still be at risk for coverage lapses when life events (such as job loss or a change in income) force transitions. Some proposals try to minimize coverage gaps by providing for the automatic enrollment of the uninsured or others into the public option. The extent to which a public option would move toward universal coverage would depend in large part on how much it would increase affordability of insurance through lower payment rates to providers and increased subsidies for individuals.

2. Who would be eligible for the public option?

Eligibility for the public option varies across proposals, and some proposals would provide for auto-enrollment of certain individuals. Examples of eligibility differences include:

- Marketplace participants only – Some proposals would offer the public option only in the marketplace; others would further limit the option to marketplace eligible individuals age 50-64.

- Employers – Employers would also have access to the public option under some proposals. Several congressional bills would allow small employers to purchase or provide group coverage through the public option, as would the proposal by presidential candidate Buttigieg; one of these bills also opens the public option to large employers and permits employees to remain in the public option if they change jobs.

- People who are offered employer coverage – Presidential candidates Biden, Buttigieg, Steyer, and Warren as well as a congressional proposal, known as Medicare for America, would adopt a more expansive approach that allows workers (and their dependents) who are offered job-based coverage to instead enroll in the public option and receive subsidies for their coverage. This approach differs from current law in that those with an offer of job-based coverage are generally ineligible for marketplace subsidies.1 Allowing people to get coverage through a subsidized public option, instead of their employer, could make the public option a particularly attractive alternative for low-wage workers and their families.

- People eligible for Medicare or Medicaid – With the exception of the congressional proposal, Medicare for America, the other public option congressional proposals would not allow people eligible for the current Medicare or Medicaid programs to enroll in the public option. Medicare for America would replace Medicare and Medicaid with the new public program. Buttigieg and Warren open the public option to individuals enrolled in Medicaid, while Biden and Steyer would allow states to shift some or all of their Medicaid enrollees into the public option. In addition, Biden, Buttigieg and Steyer would automatically enroll into the public option all eligible low-income individuals living in states that have not expanded Medicaid..Warren’s proposal would enroll all children and adults with incomes below 200% of poverty who are younger than age 50 into the public option, though individuals may opt out for other coverage.2 Warren would make older adults (50-64) eligible for expanded coverage under the existing Medicare program. The Warren approach would offer an alternative to Medicaid coverage for the majority of low-income people currently eligible for Medicaid.

- Immigrants – Most proposals would exclude undocumented immigrants from coverage. Warren would extend eligibility for marketplace subsidies to those eligible for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which would make them eligible for her public option, and Steyer would allow undocumented immigrants to enroll in the public option. Other proposals do not specify.

As noted above, several proposals would auto-enroll certain individuals into the public option with no premium, with an “opt out” if they prefer other coverage – an approach that would expand the size of the public program. The Medicare for America bill would auto-enroll everyone in the public option, while allowing people with access to qualified employer coverage to opt out.

3. How would benefits under a public option compare to other coverage?

Under the Biden and Buttigieg proposals and others the public option would cover essential health benefits, similar to marketplace qualified health plans (QHPs) and most employer-sponsored health plans.3 Biden’s proposal would extend the “full scope of Medicaid benefits” to enrollees with income up to 138% of poverty. Congressional proposals to create a Medicare buy-in option for older adults would give enrollees the same benefits as the current Medicare program, which differ somewhat from essential health benefits; for example, the current Medicare program does not have a limit on out-of-pocket spending.

Several proposals specify that reproductive services, including abortion, would be covered under the public option, and that the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits federal funding for abortion services in most circumstances, would be repealed.

Under Senator Warren’s proposal and the Medicare for America bill, the public option would cover a substantially broader set of benefits, including long-term services and supports (LTSS), dental benefits, and others. A public option that covers more comprehensive benefits with a broader network of providers than private plans could attract a sicker and more expensive population, which could increase the cost of the public option (and taxes required to support it) while relieving families and others of these expenses.

4. What about cost sharing and cost-sharing subsidies in the public option?

Rising deductibles and cost-sharing requirements are a growing concern for people with job-based and marketplace coverage. Over the past decade, deductibles in employer plans have risen six times faster than wages. The average deductible under silver-tier marketplace plans is $4,544 per person in 2020 (unweighted), though cost-sharing reduction (CSR) subsidies, available to people with income up to 250% of the federal poverty level (FPL), reduce silver plan deductibles for about half (52%) of marketplace enrollees.

Candidates Biden, Buttigieg, and Steyer would reduce ACA cost-sharing for those in both marketplace plans and the new public option. Their proposals would set the benchmark marketplace plan at the gold level, instead of silver, to lower deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs. Some proposals would expand eligibility for cost-sharing subsidies to those with income above 250% FPL, and up to 400% FPL in some cases.4 Proposals that let would employees elect the public option and receive subsidies instead of job-based coverage could extend cost sharing relief to some low-wage workers.

Warren takes a different approach. In addition to enhancing marketplace cost-sharing subsidies as do the other candidates, cost sharing under the public option would be even lower. Cost sharing in Warren’s public option would be set at the platinum level (which covers 90% of costs) instead of gold (which covers 80% of costs). In addition, deductibles would be eliminated for all public option enrollees, and there would be no cost sharing for enrollees with income up to 200% FPL. Co-insurance would apply for people with incomes above 200% FPL up to an out-of-pocket cap, but would phase out over time. These features would reduce out-of-pocket health care spending for many people relative to private insurance.

5. How would premiums and premium subsidies work?

How attractive the public option is to individuals will largely depend on the relative affordability of premiums in the public option. The availability and level of premium subsidies will be an important factor, particularly to individuals who are currently ineligible for marketplace subsidies due to income or because they are offered employer coverage. Other factors that could affect the premium in the public option include benefits and cost sharing, and provider payment rates. Premiums for public option enrollees could be higher (or lower) depending on the risk profile of individuals who elect coverage under the public option. If the public option experiences adverse selection, premiums could be higher than private insurance and rise over time, although in virtually all proposals, public option premiums would be capped as a percentage of income for enrollees.

Like marketplace plans, the public option premiums generally could vary by age, geography, family size, and tobacco use.

Most proposals would expand premium subsidies relative to those that are currently available to marketplace enrollees. Several would make the public option free for low-income people – those with income up to 200% FPL under Warren’s proposal, and up to 138% FPL for some or all people under proposals by Biden, Buttigieg, and Steyer. Many would also cap premium contributions for people with higher incomes. Premiums would be capped at 5% of income under Warren, 8% under Medicare for America, and 8.5% under Biden, Buttigieg, and Steyer. These caps are lower than the current 9.78% premium cap, which is only available to people with incomes up to 400% of poverty. Premiums would be eliminated over time under the Warren proposal. In addition, all of the candidate proposals and the Choose Medicare Act (Sen. Merkley/ Rep. Richmond) would enhance marketplace premium subsidies by changing the benchmark plan, on which subsidies are based, from silver level to gold level.

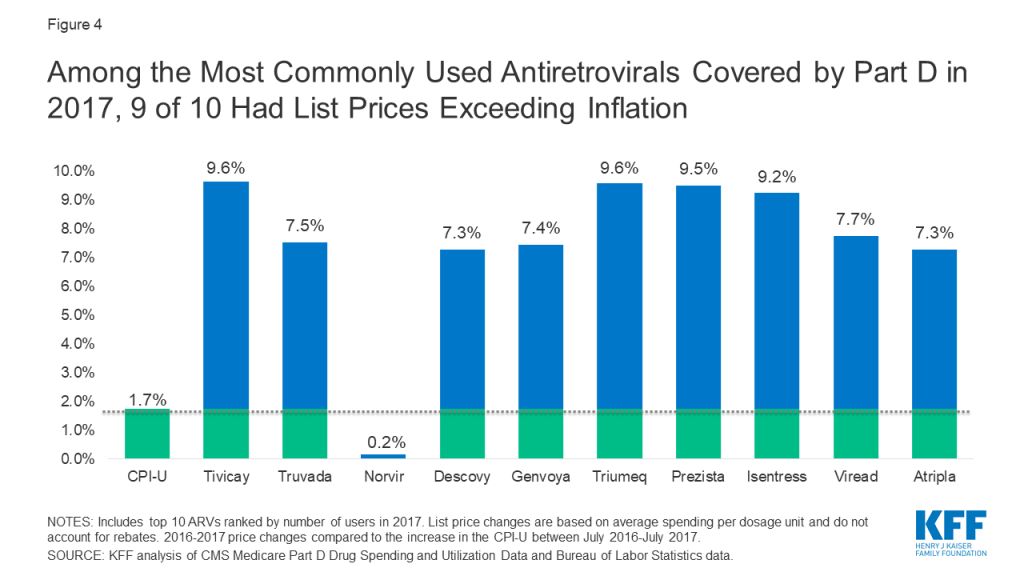

6. How would health care providers be affected?

The relative affordability of the public option would also depend on the level of provider payments. This is because private insurers typically pay higher prices than Medicare for covered services. For example, a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis found that Medicare hospital payment rates were 47% below those of commercial insurers, on average, though with wide variation by geography and other factors.5 Medicare’s role in setting payment rates has contributed to slower growth in spending for Medicare than private insurance. Adopting Medicare rates could also reduce or eliminate the problem of surprise medical bills, as Medicare limits what providers can charge and prohibits balance billing.

However, health care providers are likely to oppose this approach, based on concerns about the adequacy of payment rates, and the impact on patient care. An ongoing question is how hospitals and other health care providers would respond to lower payment rates, and whether they would be able to achieve efficiencies without jeopardizing quality of care.

- Use of Medicare payment rates – Several proposals would build on the Medicare provider payment system. The Warren proposal, for example, would phase down payment rates before ultimately paying 110% of Medicare rates for hospitals and Medicare rates for other providers once the Medicare-for-all program takes effect. Buttigieg would limit out-of-network payment rates for all hospitals and providers at 200% of Medicare rates, with the public option presumably paying no more than that; rural providers would receive higher payments. Some other proposals do not specify the level of provider payments under the public option, saying more generally that they would be “based on” Medicare rates..Another approach included in the Merkley/Richmond bill would allow self-funded employer plans to contract with the public option as a third party administrator (TPA). This would give employers access to the public option’s provider network and payment rates. Under this proposal, over time, the public option could move toward an all-payer-rate setting system, even while preserving private employer coverage and financing.

- Provider participation in the public option – Proposals also vary in whether they encourage providers to participate in the public option. Under proposals by Warren and Steyer, hospitals, physicians and other health care providers who participate in the current Medicare (and Medicaid) programs would also participate in the public option. In other proposals, such as the Medicare-X Choice Act introduced by Senator Bennet, provider participation in the public option would not be linked to participation in Medicare. Others, such as Biden and Buttigieg, do not specify.–Part of the appeal of the current traditional Medicare program is its broad and national provider network. If provider participation in the new public option is not tied to Medicare, this could result in a narrower provider network, which could be a concern for enrollees. Moreover, voluntary participation could undermine the government’s ability to set lower payment rates than it could if all or virtually all providers participated, as is now the case with the current Medicare program.

One controversial element of Medicare-for-all is that it would replace private coverage that people have today. Public option proposals would instead retain current coverage and offer an additional choice. Candidates Biden, Buttigieg, Warren and Steyer all would let people with job-based plans opt for the public option and receive subsidies for that coverage (this is also a feature of the Medicare for America bill). Warren would also offer substantially more generous benefits under the public option than most employers offer today. The relative attractiveness of the public option – e.g. due to its covered benefits or subsidies – could lead more workers to elect it over time, ultimately diminishing the role of employer coverage.

The broad availability of a public option could also lead some employers to decide to stop offering plans they sponsor today. Whether and which firms continue offering private coverage would depend on a number of factors, including how many enrollees would prefer to keep their employer plan, the average cost of covering remaining employees, and the employer’s cost of maintaining the plan relative to the cost of paying the large employer mandate penalty under the ACA. The substantial federal tax preference accorded to employer-sponsored group health benefits today could also affect decisions of firms to keep offering job-based coverage and worker decisions to participate. Unlike wages, health benefits are not subject to federal income or payroll tax.

The public option could also significantly affect non-group insurance. A public option could strengthen incentives for private insurers to compete on value and cost. A new public option could offer consumers an additional plan choice, particularly in marketplace areas served by a single insurer. On the other hand, if private insurers are unable to compete effectively, the public option could draw substantial enrollment away from them and might become the sole option in at least some areas.

8. How would public option proposals affect the current Medicare program?

All of the public option proposals would retain the current Medicare program. Although many invoke the Medicare name, such as Medicare For All Who Want It, Medicare Choice, and Medicare Part E, the new public options are intentionally structured to be separate from the current Medicare program and differ from it in many respects.

Most proposals would not allow people who are eligible for the current Medicare program to enroll in the new public option, and most leave the current program as is. Some create a firewall between the new public option and Medicare, explicitly stating that the new public option will not have any effect on premiums in the current Medicare program or finances (e.g. the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund).

Some proposals would make improvements to the current Medicare program. The Buttigieg proposal and the Merkley bill, for example, would add an out-of-pocket limit to traditional Medicare. The Higgins bill would create a new voluntary Medigap option to make cost sharing more affordable for people with Medicare. Virtually all of the proposals would address the price of prescription drugs in Medicare as they do for the public option (e.g., allow the government to negotiate lower prices). Warren’s proposal would match benefits under the current Medicare program to the public option “to the extent possible”.

In contrast to other proposals, the Warren proposal would lower the age of eligibility for Medicare to 50, but would allow people age 50-64 to go in (or out) of the Medicare program. Her proposal would automatically enroll all 50-64 year olds who are uninsured or living on incomes below 200% of poverty into the Medicare program with no premiums, deductibles or cost sharing. This approach would substantially increase the size of the current Medicare program, and could potentially affect the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund unless safeguards are put in place. At the same time, the infusion of younger adults into the current Medicare program could lead to lower per capita costs, which could result in lower Medicare premiums.

9. How would public option proposals affect Medicaid?

Proposals also differ in what happens to the Medicaid program and in how they address the coverage gap in states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion. Many congressional proposals would retain the Medicaid program and would not permit people eligible for Medicaid to enroll in the public option; they also would not address the lack of coverage for poor adults living in states that did not expand Medicaid. In contrast, the presidential candidates’ proposals and the Medicare for America bill would have broader implications for Medicaid, and most would cover low-income adults in non-expansion states.

Candidates Biden, Buttigieg, and Steyer would auto-enroll into the public option low-income uninsured individuals living in the 14 states that did not expand Medicaid. These individuals would receive free coverage through the public option. The Buttigieg plan would allow individuals who are uninsured, have private coverage or Medicaid to opt into the public option while plans offered by Biden and Steyer would allow states to shift some or all of their Medicaid enrollees into the public option and make a maintenance of effort (MOE) payment instead, though how that MOE would work is not specified. These proposals do not specify whether the public option would cover all benefits that are currently covered by Medicaid, such as LTSS and non-emergency medical transportation, for this population.

Warren’s proposal would auto-enroll into the public option, with an opt out, a much larger group of people, including people who are currently eligible for Medicaid or in the Medicaid coverage gap. Children up to age 18 would be auto-enrolled, as would adults up to age 50 with incomes below 200% of poverty. Adults age 50-64 would be eligible for Medicare. Under this proposal, the public option and expanded Medicare program would be offered as an alternative to Medicaid and CHIP. States would also be permitted to move other Medicaid enrollees into the public option and make an MOE payment instead, thus eliminating Medicaid altogether in these states.

This proposal raises a number of important questions for the Medicaid population, particularly adults age 50-64 with long-term care needs, as well as for states. For example, while the public option would guarantee coverage vision, dental, and LTSS, these benefits would only be provided to the “greatest extent possible” under Medicare. The proposal also does not specify if low-income individuals ages 50-64 in Medicare would have access to free coverage, as would be the case for younger adults and children under the public option.

Unlike other proposals, the Medicare for America bill would explicitly eliminate the Medicaid program, moving all Medicaid enrollees into the public option. To ensure Medicaid enrollees receive the same coverage under the public option, Medicare for America would cover all benefits provided by state Medicaid programs as part of the benefit package.

One congressional bill (Schatz/Lujan) differs from the others in that it would permit states to build on the existing Medicaid infrastructure to create a Medicaid-like public option. Yet, even with this proposal, the Medicaid program would remain intact for existing Medicaid enrollees — the Medicaid buy-in would target those who are eligible for marketplace coverage, not those currently eligible for Medicaid. Although it seeks to address the coverage gap, it would do so by extending 100% federal financing for the expansion for three years for any state that newly adopts the expansion. Individuals with incomes below 138% of poverty in states that continue to refuse to adopt the expansion would remain uninsured and without an affordable coverage option.

10. What do we know about the cost of these proposals?

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has not estimated any of the public option bills introduced in the 116th Congress. In general, a public option can be expected to have less of an effect on federal spending and revenues than Medicare-for-all. The federal cost of a public option could be higher or lower depending on many factors, including benefits, subsidies, the number of people who enroll, and the extent to which costs shift from individuals and other payers to the public option. Federal spending could also rise due to induced demand resulting from more people with coverage, and lower cost-related barriers to care. New federal costs could be offset somewhat to the extent the public option uses lower provider payment rates. The cost of federal marketplace subsidies could also be offset to the extent that public option premiums are lower than what commercial insurers charge today, depending on the details of how subsidies are determined.

A public option could also affect costs borne by individuals, employers and states. Proposals that provide enhanced cost-sharing and premium subsidies in the public option, and make more people eligible for these subsidies, could improve affordability for millions of Americans. However, public option proposals do not go as far as Medicare-for-all proposals that eliminate premiums and cost-sharing and provide comprehensive benefits. Employers could realize savings if employees opt into the public option, subject to contribution requirements. Employers could also achieve savings if they are able to access public option provider payment rates. The fiscal impact on states would depend on the extent to which Medicaid enrollees would shift to the public option, and related MOE requirements.

Discussion

Recent polls have shown substantial support for a public option, relative to Medicare-for-all, in part because it would give individuals another “choice” rather than require all people to be covered under one program that replaces current sources of coverage. Public support for Medicare-for-all drops when people are told that it would eliminate private insurance and employer-sponsored coverage, and threaten the Medicare program. The public option is viewed as less disruptive than Medicare-for-all, even though it could replace a significant amount of private plan coverage under some proposals. In fact, support for a public option drops when people are told it could reduce payments to hospitals and doctors or lead to too much government involvement in health care.

A public option could have a modest or significant effect on health coverage and costs in the U.S., depending on how it is structured. The effect could be minimal if the public option is available to a limited subset of the population, with benefits, cost sharing and subsidies similar to marketplace coverage, and if providers can participate voluntarily with little change in their payment rates. However, a public option could have a more dramatic impact on coverage and costs if it is widely available, offers more comprehensive benefits at lower costs, extends subsidies to people now in job-based plans, and uses Medicare provider payment rates.

Ultimately, with many different proposals on the table, it is important to examine key details that could determine the impact of a public option on coverage and affordability, and the level of disruption to the current health care system.

| Table 1: Public Option Proposals Introduced by Presidential Candidates |

| PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES’ PUBLIC OPTION PROPOSALS |

| Proposal | General Approach |

| Biden The Biden Plan To Protect & Build On The Affordable Care Act | - Creates a federal public option available to marketplace-eligible individuals, people with employer coverage, and low-income adults in the Medicaid coverage gap; low-income uninsured in coverage gap states automatically enrolled

- Allows Medicaid expansion states to move expansion adults into the public option with MOE

- Covers ACA essential health benefits; provides “full scope of Medicaid benefits” to those <138% FPL

- Sets Gold-level plan as marketplace benchmark plan to increase premium subsidies and lower deductibles and out-of-pocket costs for all marketplace enrollees

- Eliminates income limit on eligibility for premium tax credits and caps premium payments at 8.5% of income; no premiums <138% FPL; those with job-based coverage eligible for subsidies

- Negotiates payments to providers; provider participation requirements not specified

|

| Buttigieg Medicare For All Who Want It | - Creates a federal public option available to marketplace-eligible individuals, people with employer coverage and Medicaid; low-income uninsured in coverage gap states automatically enrolled

- Allows employers to buy into the public option

- Covers ACA essential health benefits

- Sets Gold-level plan as marketplace benchmark plan to increase premium subsidies and lower deductibles and out-of-pocket costs for all marketplace enrollees

- Eliminates income limit on eligibility for premium tax credits and caps premium payments at 8.5% of income; no premiums <138% FPL; those with job-based coverage eligible for subsidies

- Pays rural hospitals and certain other providers higher than current Medicare rates; provider participation requirements are not specified

|

| Steyer Every American Has a Right to Health Care | - Creates a federal public option available to marketplace-eligible individuals, people with employer coverage, low-income adults in the Medicaid coverage gap, and undocumented immigrants; low-income uninsured automatically enrolled in public option or Medicaid

- Allows Medicaid expansion states to move covered adults into the public option; small employers can buy into public option

- Sets Gold-level plan as marketplace benchmark plan to increase premium subsidies and lower deductibles and out-of-pocket costs for all marketplace enrollees

- Caps premium payments at 8.5% of income for those above 400% FPL; no premiums <138% FPL; those with job-based coverage eligible for subsidies

- Negotiates payments to providers; providers that participate in Medicare or Medicaid must participate in public option

|

| Warren My First Term Plan For Reducing Health Care Costs In America And Transitioning To Medicare For All | - Creates a federal public option available to all children, and adults who are not otherwise eligible for Medicare; auto-enrolls all children and low-income uninsured under age 50, with opt out for other coverage allowed

- Encourages states to move Medicaid enrollees into the public option with MOE

- Covers essential health benefits, dental, vision, hearing, and long-term care in public option

- Eliminates premiums and cost sharing in the public option for all children, and adults below 200% FPL. For other adults, sliding scale premiums capped at 5% of income and cost sharing scaled modestly with caps on out-of-pocket costs; no deductibles; people offered job-based coverage eligible for public option subsidies; premiums and cost sharing eliminated over time

- Sets Gold-level plan as marketplace benchmark plan; lifts income limit for eligibility for premium subsidies and lowers cap on premium payments for all marketplace enrollees; increases eligibility for cost sharing subsidies

- Requires Medicare providers to participate in public option; payment rates set higher than Medicare rates initially but gradually reduce to Medicare rates

- Expands Medicare eligibility to adults 50-64; uninsured adults 50-64 are automatically enrolled in expanded Medicare with opt out for other coverage allowed and adds dental, vision, hearing and LTC to the “greatest extent possible”

|

| CONGRESSIONAL PUBLIC OPTION PROPOSALS |

| Proposal | General Approach |

| Cardin S.3, Keeping Health Insurance Affordable Act of 2019 | - Creates a federal public option available to marketplace-eligible individuals

- Does not change marketplace subsidies

- Requires Medicare providers to participate in public option; Medicare payment rates used initially, with adjustments by the Secretary starting in 2023

|

| Stabenow/ Higgins S 470, HR 1346, Medicare at 50 Act | - Creates a Medicare buy-in option for individuals 50 and over

- Applies marketplace premium and cost sharing subsidies to the Medicare buy-in; cost sharing subsidies enhanced for others in Marketplace (Higgins only)

- Covers Medicare benefits; Medicare cost sharing applies for those not eligible for subsidies

- Pays Medicare rates for the buy-in, and providers that participate in Medicare also participate in the buy in

|

| Schatz S.489, State Public Option Act | - Allows states to offer a public option based on Medicaid

- States set premiums and cost sharing, federal matching payments for any losses; no other changes to marketplace subsidies’

- Pays Medicare rates to primary care providers, Medicaid rate to all others; Medicaid providers and managed care organizations participate in public option

|

| Bennet/ Delgado S.981 / H.R.2000, Medicare-X Choice Act of 2019 | - Creates a federal public option available to marketplace-eligible individuals

- Enhances marketplace subsidies for eligible participants

- Requires Medicare providers to participate in public option; Medicare payment rates used; Secretary may increase payments up to 25% for rural providers

|

| Schakowsky H.R.2085, CHOICE Act | - Creates a federal public option available to marketplace-eligible individuals

- Does not change marketplace subsidies

- Requires Medicare providers to participate in public option, with opt out; Secretary to negotiate payment rates, with current Medicare rates as default

|

| Merkley S.1261, Choose Medicare Act | - Creates a federal public option available to marketplace-eligible individuals and large and small employers

- Permits large, self-funded employer plans to hire public option as third-party administrator

- Enhances marketplace subsidies for eligible participants

- Requires Medicare providers to participate in public option; Secretary establishes public option provider payment rates between Medicare and commercial rates

|

| DeLauro H.R.2452, Medicare for America Act of 2019 | - Creates a federal public program with comprehensive benefits available to all U.S. residents with allowable opt-out for other qualified coverage

- Eliminates premiums and cost sharing below 200% of the FPL; income-related premiums and cost sharing to 600% FPL with cap on premium payments of 8% of income

- Covers essential health benefits, dental, vision, hearing, long-term care, all other current Medicaid-covered benefits

- Requires Medicare and Medicaid providers to participate in public option; higher of Medicare or Medicaid payment rates used with hospitals paid 110% of applicable rate

- Replaces marketplaces, Medicaid, individual health insurance, Medicare, and CHIP; employers can continue to offer qualified group plan coverage

|

| NOTES: Candidate proposals are listed by order of introduction within each category. Amy Klobuchar also supports a public option, per her campaign website, but does not outline a specific proposal. Andrew Yang announced his support for giving employees the option to enroll in Medicare-for-all instead of an employer plan. Elizabeth Warren has also introduced a separate proposal for Medicare-for-all; she describes her public option plan as a transition to Medicare-for-all. Congressional proposals are listed by order of introduction within each category. For more detail on congressional bills, see Compare Medicare-for-all and Public Plan Proposals |