More than 170 million people in the US are covered by many different group and individually purchased private health plans. People cannot take for granted that every plan covers the same benefits, applies the same cost sharing and utilization review standards, or offers access to the same network of participating hospitals, doctors, labs, and other providers. Research demonstrates that out-of-pocket costs can, and frequently do, effectively limit access to needed care for insured patients. Public health experts warn that efforts to control spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 will be less effective if people fail to seek appropriate diagnosis or care due to the cost.

Congress recently passed a new law, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, that will, among other things, require most private health plans to cover testing for the coronavirus with no cost sharing during the emergency period. Some states have adopted similar requirements for insurers they regulate, and many private insurance companies will voluntarily expand coverage for testing.

To date, fewer changes have been adopted or considered with respect to treatment for complications from the disease.

This brief reviews current coverage standards for private health plans and how these may change in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

What health services might patients need for COVID-19?

COVID-19 is an infectious respiratory disease caused by a new coronavirus. No vaccine or cure or specific treatment for COVID-19 has yet been developed.

Testing – Diagnosis of COVID-19 is confirmed by a test that is currently available via public health departments and, increasingly, via private laboratories. Testing also typically involves a visit to a physician office, clinic, or emergency room to collect the patient’s specimen.

Treatment – Once diagnosed, treatment for complications from COVID-19 would vary based on the patient and severity of the case. According to the World Health Organization, 80% of people who become infected will recover without needing special treatment. However more than 105 million adults in the U.S. have a higher risk of developing serious illness if they are infected with coronavirus, due to their older age (60 and older) or health condition, that could require more extensive care, such as hospitalization, respiratory therapy and other services.

What does private health insurance cover?

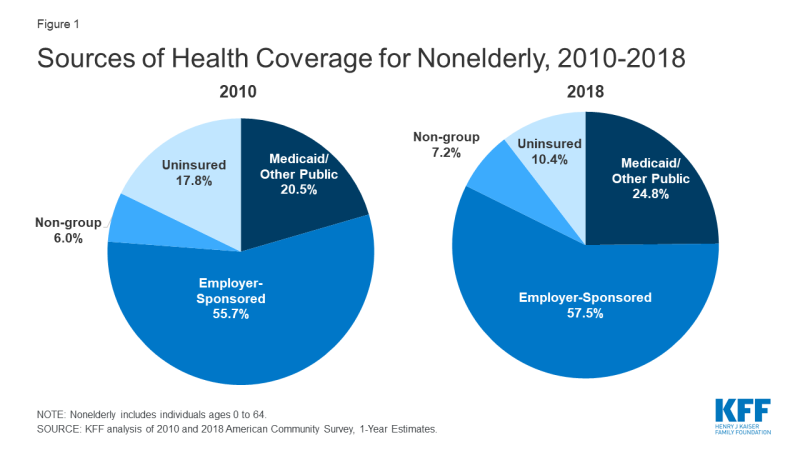

Most Americans under the age of 65 (about 6 in 10) are covered under one of many different job-based group health plans. Another 7 percent of the nonelderly are covered under one of thousands of different private insurance policies offered in the non-group market.

To understand what private health insurance covers, one must consider

- what benefits and services are covered under a plan;

- what level of cost sharing, if any, applies to covered benefits;

- how, if at all, the plan covers care from out-of-network providers, which could result in “balance billing.”

In general, private plans can vary in each of these respects.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) sets a few minimum coverage standards that apply to most private health plans. For example, the ACA requires most private plans to cover designated preventive services with no cost sharing. Even these ACA coverage standards do not apply to all private coverage, however, including short-term policies, health care sharing ministries, and certain Farm Bureau health plans that are not subject to any federal minimum coverage standards.

States also regulate and set coverage standards for private health plans, although a federal law, ERISA, preempts state regulation of many employer-provided health plans.

Within this regulatory framework, private health plans vary, at least to some extent, in terms of their covered benefits, cost sharing, and benefit limits.

Benefits

The ACA requires policies in the individual and small group health insurance markets to cover 10 categories of essential health benefits (EHB), including hospitalization, ambulatory care, lab tests, and prescription drugs. However, the details of covered benefits within each category can and do vary from plan to plan – for example, whether the ambulatory care EHB category covers telemedicine visits. In addition, large group health plans and self-insured group health plans of any size are not required to cover EHB, though most provide major medical coverage.

Coronavirus testing – The new law passed by Congress requires all group health plans and individual health insurance coverage to cover testing and associated visits related to the diagnosis of the COVID-19 during the emergency period.

This new law will not apply to some types of private coverage sold to individuals. For example, regulations issued by the Trump Administration in 2018 promote the sale of short-term policies that are not required to cover EHB.

In addition, health care sharing ministries are a private health coverage arrangement not subject to federal standards.

Also, two states have authorized their Farm Bureaus to sell private coverage that, explicitly, is not defined or regulated as health insurance.

- As of 2017, 73,000 people were enrolled in Farm Bureau plans in Tennessee. The State of Iowa also has a law specifying that private coverage offered by the Farm Bureau is not insurance.

Under the new federal law, however, people enrolled in these types of non-compliant private coverage will be considered uninsured. The law also gives states the option to provide free Medicaid coverage for coronavirus testing for their uninsured residents. In addition, the new law appropriates $1 billion to the National Disaster Medical System to reimburse providers for the costs associated with diagnosis and testing of uninsured individuals.

Treatment for complications of COVID-19 – While most private health plans likely cover most items and services needed to treat complications due to COVID-19, there is no clear federal requirement to do so.

The EHB standard under the ACA defines categories of services to be covered, but it is left to states to designate “benchmark” policies that define specific covered services. As a result, coverage for at least some services needed to treat COVID-19 – such as home-delivered care, telemedicine visits, or respiratory therapy visits – could vary under health insurance plans that are subject to EHB.

Large employer health plans are not required to cover EHB. Most large employers offer major medical coverage under their group health plans, but some do not.

- About 4 percent of large firms offer so-called “mini-med” plans to some or all workers as a less expensive option. For example, one mini-med plan currently marketed covers preventive services, 4 doctor visits per year, and no hospitalization or emergency care. Such plans would provide limited, if any coverage, for services to treat complications of COVID-19.

Short-term plans, health sharing ministries, and certain Farm Bureau plans are not subject to any federal coverage standards. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act does not address coverage of COVID-19 treatment costs for people who are uninsured.

Cost sharing

Private health plans typically apply cost sharing – deductibles, copays, or coinsurance – to covered benefits other than preventive services.

Coronavirus testing – The Families First Coronavirus Response Act requires all group health plans and individual health insurance coverage to waive all cost sharing for testing and associated visits related to the diagnosis of the COVID-19 during the emergency period.

Coronavirus vaccine – Certain preventive services under ACA-regulated private plans must be covered with no cost sharing. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, and other agencies are tasked with periodically reviewing and recommending preventive services to be covered under this requirement, and this would likely include a coronavirus vaccine, if developed. The ACA preventive services coverage requirement takes effect for each new service 1 year after it is recommended.

Treatment for complications of COVID-19 – There is no federal requirement for private plans to waive cost sharing for COVID-19-related treatment. While many private health insurers recently announced they will voluntarily waive cost sharing for testing, industry leaders have clarified that this waiver does not generally apply to treatment. The ACA limits the amount of cost sharing that can apply for in-network covered benefits under most private plans to $8,150 in 2020 for single coverage, $16,300 for family policies. Within these limits, privately insured COVID-19 patients could face significant out-of-pocket costs for covered care.

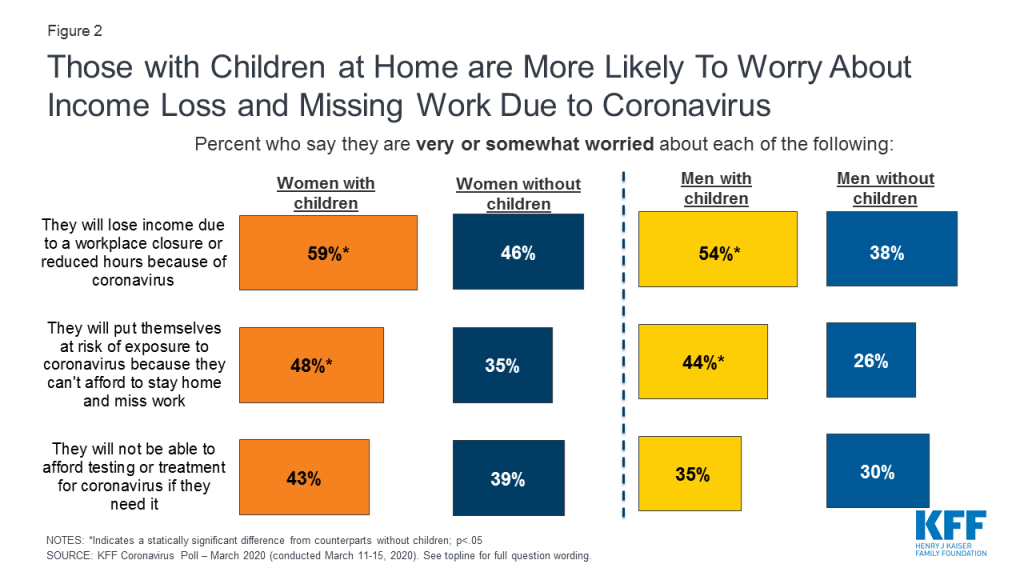

- Increasingly, cost sharing is becoming unaffordable for many private health plan enrollees. Half of adults covered under job-based plans report foregoing or delaying needed care in the past year due to cost. Among adults who do skip or delay needed care due to cost, 13% report their health condition worsened as a result.

- Among covered workers in job-based plans with a deductible for self-only coverage in 2019, the average deductible was $1,655. Employer-sponsored health plan deductibles have increased six times faster than average wages over the past decade.

- Under non-group plans, deductibles are even higher – on average more than $4,500 for self-only coverage in silver plans this year – although half of marketplace enrollees qualify for subsidies to significantly reduce deductibles and other cost sharing.

Provider networks

Nearly all private health plans use networks of participating hospitals, doctors, laboratories, and other providers, which could have implications for those in need of coronavirus testing or care, depending on where they present for services. Claims for out-of-network services, other than emergency services, can be denied by HMOs and other plans with closed networks. Under PPO plans that provide some coverage for out-of-network care, patients can be face higher cost sharing (e.g. patients might be required to pay 20% coinsurance for in-network claims and 50% coinsurance for out-of-network claims.)

In addition, out-of-network care exposes patients to “balance billing,” or the difference between the provider’s undiscounted charge and the amount the health plan considers reasonable. Private plan enrollees generally try to seek care from in-network providers, though sometimes they receive out-of-network care inadvertently, resulting in surprise medical bills.

- Analysis of emergency visits by patients covered by large employer plans found 18% included at least one out-of-network charge.

- Among non-emergency stays at in-network hospitals and facilities, 16% involved at least one out-of-network claim (e.g., by an anesthesiologist).

Coronavirus testing – Surprise medical bills could result if patients seek testing in an emergency room; even at an in-network emergency facility, physicians and other providers who work there may not be in-network. Surprise medical bills could also result in other ambulatory care settings, for example, if a patient’s in-network primary care doctor sends her test to an out-of-network commercial lab.

Treatment for complications of COVID-19 – Patients could also receive surprise out-of-network bills for treatment services, particularly when patients are hospitalized. New analysis finds that patients hospitalized at in-network hospitals for pneumonia (one complication that can arise from COVID-19 infection) are 20% more likely than average to incur at least one out-of-network charge.

Other limits on covered benefits

In addition to network restrictions on covered benefits, most private plans employ other medical management and utilization review techniques, such a requiring referrals or prior authorization for certain services before they will be covered, which could also have implications for those with COVID-19. Congress is poised to enact a law requiring waiver of prior authorization for coronavirus testing.

For most private plans, the ACA prohibits most annual or lifetime dollar limits on covered benefits, and prohibits plans from denying coverage for pre-existing conditions. These standards do not apply to short-term plans, health sharing ministries or to certain Farm Bureau plans.

Changes in Private Plan Standards for COVID-19

The policy landscape is changing rapidly as the outbreak spreads. Notable recent developments include:

The new law passed by Congress requires ACA-regulated health plans to cover coronavirus testing and to waive cost sharing and prior authorization. In addition to the test, itself, this requirement applies to visits in physician offices, urgent care centers, and emergency rooms associated with testing. This standard does not apply to short-term plans, sharing ministries, or certain Farm Bureau plans. The law does not address standards for private health plan coverage or cost sharing for COVID-19 treatment. Nor does it address balance billing.

Voluntary coverage changes by the insurance industry – Before Congress acted, many private health insurers had announced voluntary efforts to extend and expand coverage for coronavirus testing under their fully-insured policies, although in general, private insurers have not addressed balance billing (surprise bills). A few private insurers, including one serving federal employees, committed to waiving cost sharing for COVID-19-related treatment, as well. Insurers making coverage changes not otherwise required by law note that self-insured group health plans, which they administer, have the option to adopt or reject these changes. Sixty percent of covered workers in employer-sponsored plans are in self-insured coverage arrangements.

Changes in requirements for state-regulated plans – A number of state insurance commissioners have issued directives to health insurers they regulate regarding COVID-19. For example, in Washington state, all state-regulated health insurance plans and short-term medical plans must suspend prior authorization for treatment or testing of COVID-19, waive cost sharing for testing, and allow enrollees to receive testing and treatment from an out-of-network medical provider if the plan’s network does not provide reasonable access. The order also requires plans to allow enrollees a one-time refill of prescription medications before the waiting period on refills expires. In New York, guidance requires state regulated plans to cover COVID-19 testing and waive cost sharing for the lab test and the associated patient visit to in-network physician offices, urgent care centers, or emergency departments. New York-regulated insurers also must cover out-of-network testing if in-network providers are unable to provide COVID-19 testing, waive prior authorization for COVID-19 testing, and cover telehealth services. New York’s surprise medical bill protections also apply for patients who receive out-of-network bills in certain circumstances, including when in-network physicians send specimens to an out-of-network laboratory or pathologist for testing.

Federal law preempts state regulation of employer-sponsored health plans.