Round 3: Legal Challenges to Contraceptive Coverage at SCOTUS

Key Takeaways

- For the third time, legal challenges to the regulations that implement the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) contraceptive coverage requirement have been brought before the Supreme Court. This requirement, which took effect in August 2012, provides a guarantee of no-cost contraceptive services and supplies to most women with private insurance (with the exception of those who work for a house of worship or are in a grandfathered plan).

- In November 2018, The Trump Administration issued final regulations greatly expanding the types of employers that are exempt from the ACA contraceptive coverage requirement. One of the regulations allows any nonprofit or for-profit employer with an objection to contraceptive coverage based on religious beliefs to qualify for a full exemption and drop contraceptive coverage from their plans. The other regulation exempts employers with moral objections to contraception from rule with the exception of those who are publicly traded.

- Seventeen states and DC have challenged the Trump regulations. In the challenge brought by PA and NJ, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s decision to issue a nationwide stay, thus temporarily blocking the regulations from being implemented.

- The Trump Administration and the Little Sisters of the Poor (LSOP), a religious nonprofit serving the elderly poor, have appealed the case to the Supreme Court. The states challenging the Trump regulations contend that the regulations exceed agency authority, while the Trump Administration says the law at least permits, if not requires, the expanded employer exemptions.

- The ruling will determine whether nearly any employer has the right to be exempt from a regulation to which they have religious or moral objection or whether women and their dependents have a right to no-cost contraceptive coverage under the ACA. Depending on the outcome, the ruling could also pave the way for broader religion exemptions to laws protecting LGBTQ people, people living with HIV, and others from discrimination in the work place, in health care settings, in housing, and other areas of society.

Introduction

On May 6, 2020, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments for Trump v. Pennsylvania, and a related case, Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, marking the third round of litigation involving the Affordable Care Act’s regulations on contraceptive coverage that has reached the high court. In these cases, it is Pennsylvania and New Jersey, not religious employers, that are leading the challenge to the Trump Administration’s contraceptive coverage regulations under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) giving employers wide latitude to claim an exemption from the requirement. In previous cases, the Supreme Court rulings tried to balance the beliefs of religious employers with women’s entitlement to receive no-cost contraceptive coverage. Since the Court last considered these regulations, Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh have joined the Court forming a solid conservative majority that may influence the outcome of these cases. This brief explains how the new regulations issued by the Trump Administration would change the contraceptive coverage requirement for employers and affect women’s coverage, the legal positions for challenging and defending these regulations, the potential rulings, and the broader ramifications.

Background

The ACA is the first law to set preventive coverage requirements for health insurance across all markets – individual, small group, large group and self-insured plans. As part of these preventive requirements, there is a provision that charges the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to identify preventive services for women. Starting in 2012, HRSA required all new private plans were to cover, without cost-sharing, the full range of contraceptive services and supplies approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as prescribed for women. In 2018, an estimated 43.3 million women ages 15 to 49 had employer sponsored health insurance. The ACA contraceptive coverage rules implementing this recommendation have evolved through litigation and new regulations.

While the cases currently before the Supreme Court involve the Trump Administration’s regulations published in November 2018, at the core of these cases is an unresolved issue from the previous litigation. Although the Supreme Court has previously reviewed two cases involving challenges from religious employers to the ACA contraceptive coverage requirement, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby and Zubik v. Burwell, the Court never decided whether the Obama Administration’s regulations violate the religious rights of religiously affiliated nonprofit employers. While PA and NJ contend there is no legal justification for the Trump Administration‘s regulations expanding employer exemptions, the Trump Administration and the LSOP maintain that the accommodation crafted by the Obama Administration violates the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and that the Supreme Court needs to address this undecided issue from Zubik v. Burwell.

RFRA was enacted in 1993 to protect “persons” from generally applicable laws that burden their free exercise of religion. The employers that challenged the Obama regulations asserted that the regulations violated RFRA. When an individual with a sincerely held religious belief challenges a law that “substantially burdens” their exercise of religion, the Act requires the government to show the law furthers a “compelling interest” in the “least restrictive means.” In the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the “closely held” for-profit corporations had religious beliefs that were being substantially burdened by the contraceptive coverage requirement. In the Court’s Hobby Lobby ruling, Justice Alito, wrote about the accommodation as a “less restrictive means,” to provide contraceptive coverage. The Court, however, did not decide whether the accommodation is lawful: “We do not decide today whether an approach of this type complies with RFRA for purposes of all religious claims. At a minimum, however, it does not impinge on the plaintiffs’ religious belief that providing insurance coverage for the contraceptives at issue here violates their religion, and it serves HHS’s stated interests equally well.”

In May 2016, with only eight justices, the Supreme Court remanded Zubik v. Burwell, sending seven cases brought by religious nonprofits objecting to the contraceptive coverage accommodation back to the respective district Courts of Appeal. The Supreme Court instructed the parties to work together to “arrive at an approach going forward that accommodates petitioners’ religious exercise while at the same time ensuring that women covered by petitioners’ health plans receive full and equal health coverage, including contraceptive coverage.” The Court also stated: “Nothing in this opinion, or in the opinions or orders of the courts below, is to affect the ability of the Government to ensure that women covered by petitioners’ health plans ‘obtain, without cost, the full range of FDA approved contraceptives.’”

However, the Trump Administration has stated that they do not believe it is feasible to resolve the religious objection of employers while still ensuring that the affected women receive full and equal health coverage that includes contraceptive coverage. Instead, the Administration suggests women could receive contraceptive services through Title X clinics or other governmental programs. However, most women who lose employer coverage for contraceptives will likely not qualify for free Title X services designed to offer services to low-income women, and over 25% of clinics have recently dropped out of Title X program in response to other Trump Administration regulations.

In October 2017, one week after issuing interim final regulations to expand the exemptions to the contraceptive requirement, the Trump Administration negotiated settlements with many of the nonprofit employers with ongoing legal challenges to the Obama contraceptive coverage regulations. The settlements give these employers permission to exclude contraceptive coverage from their plans, and in some case paid for some of the organizations’ legal fees.

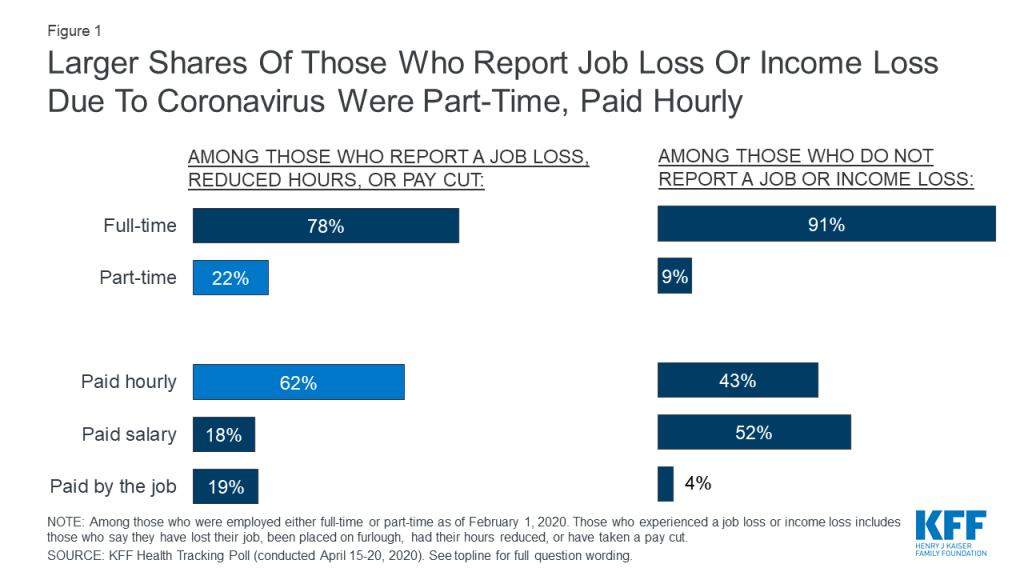

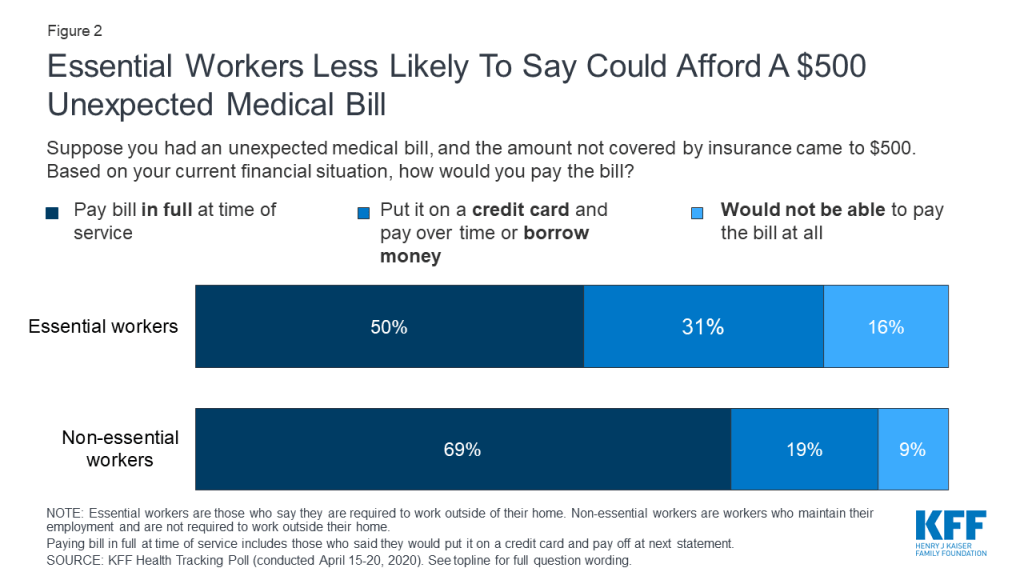

After issuing interim final rules without notice or comment, the Trump Administration issued final regulations in November 2018 greatly expanding the types of employers that may be exempt from the ACA‘s contraceptive coverage requirement (Figure 1). The Trump Administration’s final regulations greatly expand eligibility for the exemption to all nonprofit and closely-held for-profit employers with objections to contraceptive coverage based on religious beliefs or moral convictions, including private institutions of higher education that issue student health plans. In addition, publicly traded for-profit companies with objections based on religious beliefs also qualify for an exemption. There is no guaranteed right of contraceptive coverage for their female employees and dependents or students.

The accommodation developed by the Obama Administration is broadened to be available to any employer now eligible for the exemption as well as employers that previously qualified for the accommodation. The Trump Administration argues that these new rules will have only a limited impact on the number of women losing contraceptive coverage. How many employers who were not eligible for either the exemption or accommodation under the Obama-era regulations will now seek a full exemption is unknown, as is the number of employers previously utilizing the accommodation who will now opt for an exemption (resulting in the loss of contraceptive coverage for their employees and dependents). In the preamble to the regulations, Health and Human Services (HHS) estimates between 70,500 and 126,400 women would lose contraceptive coverage, and that the cost of losing contraception is $584 per woman annually and therefore the financial transfer effects attributable to these final rules on those women would be between approximately $41.2 million and $73.8 million.

Legal Basis of the Lawsuit

Unlike the previous litigation challenging the Obama Administration’s regulations, the plaintiff states are not claiming the regulations violate RFRA, however the Trump Administration is using RFRA to defend their authority to issue the regulations. The States challenging the regulations contend that thousands of women would be without birth control coverage due to these rules and may turn to state-funded programs to receive contraception and the states will incur additional healthcare costs due to an increase in unintended pregnancies. The states are arguing that they also “possess strong interests in protecting the medical and economic health or their residents, minimizing unintended pregnancies and abortions, and ensuring that all of their residents—both men and women— are free and able to fully participate in the workforce, maximize their social and economic status, and contribute to their economies without facing discrimination on the basis of sex.” They argue federal agencies lack the authority either from RFRA or the ACA to create these new expanded exemptions, and that the regulations violate the civil rights protections in the ACA prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex and other protected categories in most healthcare programs and categories.

In this case, the religious employers and the Trump Administration are aligned, and they contend that RFRA at least authorizes, if not requires, the federal agencies to create the broader religious exemptions. They also maintain that the ACA authorizes the new moral exemptions. In the preamble to the regulations, the Trump Administration explains that the moral exemption is necessary to “protect sincerely held moral objections of certain entities and individuals. The rules, thus, minimize the burdens imposed on their moral beliefs, with regard to the discretionary requirement that health plans cover certain contraceptive services with no cost-sharing, which was created by HHS through guidance promulgated by the Health Resources and Services.” Both the Administration and the LSOP contend that the ACA grants HRSA, and in turn the Agencies, significant discretion to shape the content and scope of any preventive services guidelines adopted pursuant to the preventive services provisions of the ACA, and this discretion includes shaping which entities must include coverage for all the preventive services. The Administration further explains in the preamble to the regulations, “Congress’s grant of discretion in section 2713(a)(4), and the lack of a mandate that contraceptives be covered or that they be covered without any exemptions or exceptions, lead the Departments to conclude that we are legally authorized to exempt certain entities or plans from a contraceptive Mandate if HRSA decides to otherwise include contraceptives in its Guidelines.” The Administration counters the states’ argument that the regulations discriminate on the basis on sex by stating that “any distinctions in coverage among women are not premised on sex, but on the existence of a religious or moral objection to facilitating the provision of contraceptives. Thus, the Rules do not violate Title VII’s prohibition on sex-based disparate treatment.”

The other major issues in dispute include whether the Trump Administration violated the Administrative Procedure Act, and whether a national injunction blocking implementation of the regulations for the whole country is the appropriate remedy or whether the remedy should be limited to the plaintiff states (Table 1).

One of the controversies is whether the Little Sister of the Poor (LSOP) has legal standing to appeal this case. In May 2018, with the Trump Administration no longer defending the Obama regulations, the LSOP obtained a permanent injunction from the federal district court of Colorado blocking government enforcement of the Obama regulations against the LSOP. As result, the Third Circuit found that the LSOP no longer have an injury and therefore denied appellate standing to the LSOP. The LSOP maintain they could be injured if they switch health plans, and the broad exemptions allowed by the Trump regulations are not implemented (Box 1).

| Table 1: Summary of the Parties’ Legal Positions | |

| Question: Did the Trump Administration violate the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) which governs the process by which federal agencies develop and issue regulations? The APA includes requirements for notice, public comment, and standards for judicial review | |

PA and NJ Position:

| Trump Administration & LSOP Position:

|

| Question: Do the federal agencies have the statutory authority to promulgate the final rules? | |

PA and NJ Position:

| Trump Administration & LSOP Position:

|

| Question: Do the Little Sisters of the Poor have legal standing to appeal this case? | |

PA and NJ Position:

| Little Sisters of the Poor Position:

|

| Question: Is it proper to issue a nationwide injunction in this case? | |

PA and NJ Position:

| Trump Administration & LSOP Position:

|

Box 1: The Little Sisters of the Poor and the ACA Contraceptive Coverage Requirement

The Little Sisters of the Poor, an international order of religious women devoted to caring for the elderly, have been challenging the contraceptive coverage requirement since 2013. Represented by the Becket Fund, they contend the accommodation crafted by the Obama Administration did not address their concerns, and they were part of a class action lawsuit filed in September 2013. In 2013, both the US District Court for the District of Colorado and the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals denied their request for relief, on the grounds that the accommodation was not a substantial burden. The LSOP then filed an emergency appeal with the Supreme Court, and Justice Sonia Sotomayor granted an emergency injunction while the litigation continued.

Special Rules for Self-Insured Church Plans: LSOP, have a self-insured church plan, which is a plan “established and maintained for its employees (or their beneficiaries) by a church or by a convention or association of churches.” Church plans are not limited to traditional church entities, but may include entities controlled by or associated with a religious denomination such as church-related hospitals, educational institutions and nonprofits that provide services to the aging, children, youth and family. Because church plans are not regulated by ERISA like other self-insured plans, they are not required to follow the ACA-related health reform mandates incorporated into the ERISA law. The Internal Revenue Code also lacks the authority to compel third party administrators of church plans to provide contraceptive coverage. Any provision of coverage made by a third party administrator for a self-insured church plan would be entirely voluntary. The third party administrator that operates the LSOP’s church plan is Christian Brothers Services, which also objects to contraceptive services. It is not clear that the LSOP have ever been subject to enforcement of the contraceptive coverage requirement.

Current Status and Legal Standing: In May 2018, with the Trump Administration no longer defending the Obama regulations, the LSOP obtained a permanent injunction from the federal district court of Colorado blocking government enforcement of the Obama regulations against them. In the current case, the LSOP continue to maintain that this injunction is dependent on them keeping their current health insurance plan, and they therefore hypothetically could be subject to the contraceptive coverage requirement at a later date if the Trump Administration’s broad exemptions are not implemented. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals found that the LSOP no longer have any injury and lack standing. LSOP has appealed this decision on standing, as well as the merits of the case, to the Supreme Court.

Potential Rulings and Broader Ramifications

If the Court does not hold that the violations of the APA are consequential, federal agencies may bypass notice and comment periods in the future. If the court rules that the Trump Administration violated the APA, then the Administration would need to start over by properly posting proposed regulations with notice and a public comment period. With upcoming election in November, there is a possibility the rulemaking would not be complete while President Trump is in office. If the Obama regulations remain in effect, the Little Sisters of the Poor and other religious nonprofits would undoubtedly continue to challenge these regulations, but women would still have access to contraceptive coverage regardless of their employers’ religious or moral beliefs.

Given the current conservative majority, the Court may rule that RFRA requires the broad religious exemptions. However, RFRA does not include moral exemptions, and it is therefore less clear how the Court will view the moral exemptions. If the Court allows Trump Administration’s new regulation for religious exemptions to go into effect, it is unknown how many of employers and colleges will opt for the exemption, leaving their students, employees and dependents without no-cost coverage for the full range of contraceptive methods. For some women, choice of contraceptive methods may be limited by cost, placing some of the most effective yet costly methods out of financial reach. In addition, the decision may encourage similar broad religious exemptions regarding coverage for other services without regard to harm to people who are guaranteed these services under the ACA. The Trump Administration is likely to publish final regulations that remove protections for LGBTQ patients from discrimination granted by the anti-discrimination provisions of Section 1557 of the ACA. These new regulations will likely be challenged, and the Supreme Court’s decision in the current contraceptive coverage case could support or rebuke HHS’s authority to create these sweeping changes.

Unless the Court rules in favor of the States, it does not have to issue a decision about the scope of the injunction ordered by the district court and upheld by the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. However, even if the Court rules in favor of the Trump Administration, it may want to weigh in on the practice of district courts issuing national injunctions for federal policies. This practice has become more common in the last decade, and is controversial. Proponents of national injunctions argue they are necessary to ensure the law is uniform throughout the country. Critics of nationwide injunctions contend they are overly broad, and do not give the opportunity for other courts to decide the issue for their jurisdiction. In a case brought by California and four other states challenging the Trump Administration’s interim final regulations for contraceptive coverage, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals limited the scope of the preliminary injunction issued by the district court to plaintiff states. Attorney General Barr has called for an end to nationwide injunctions. Justice Thomas wrote in a concurring opinion in Trump v. Hawaii in 2019 that nationwide injunction are “legally and historically dubious.” If the Court issues a ruling limiting the scope of injunctions, the decision could impact other cases challenging federal policies and result in federal policies becoming effective in some states, while being blocked in other states.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court will likely publish its ruling in late June 2020. The Obama administration tried to accommodate employers with religious objections and still guarantee women full contraceptive coverage without cost sharing. In contrast, the Trump Administration has acknowledged they do not think this is possible, and have prioritized broad exemptions for employers over women’s coverage. While the case once again pits the rights of women to receive health insurance that includes no-cost coverage for contraceptive services and supplies against those of employers who hold religious and moral objections to contraceptives, the ruling could have implications that go far beyond birth control coverage for thousands of women. The decision could also pave the way for broad exemptions to other laws protecting LGBTQ people, people living with HIV, and others from discrimination in the work place, in health care settings, in housing, and other areas of society. The contraceptive coverage provision of the ACA has been one of the most litigated aspects of the law. This could be final case or if the Court does not allow these broad exemptions, employers with religious or moral objections will likely continue to challenge the regulations.