Consumer Assistance in Health Insurance: Evidence of Impact and Unmet Need

Summary

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) created new health coverage options and financial assistance to expand coverage and help people remain insured even when life changes, such as job loss, might otherwise disrupt coverage. The ACA also established in-person consumer assistance programs to help people identify coverage options and enroll. A variety of professionals provide consumer assistance, including Navigator programs that are funded through state and federal marketplaces, brokers who receive commissions from insurers when they enroll consumers in private health plans, local non-profit organizations, and health care providers. Recent funding cuts have reduced the availability of Navigator programs.

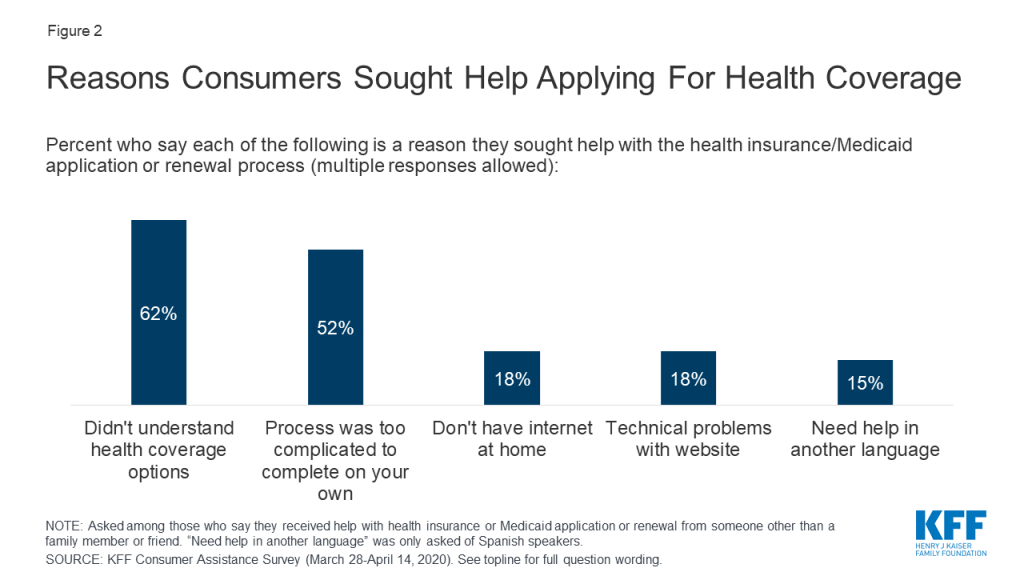

In the spring of 2020, KFF surveyed consumers most likely to use or benefit from consumer assistance—nonelderly adults covered by marketplace health plans (also called qualified health plans, or QHPs) or Medicaid, and people who were uninsured—to learn who uses consumer assistance, why they seek help, and what difference it makes as well as who does not get help and why. The survey also explored differences in help provided by marketplace assister programs and brokers. Key findings include:

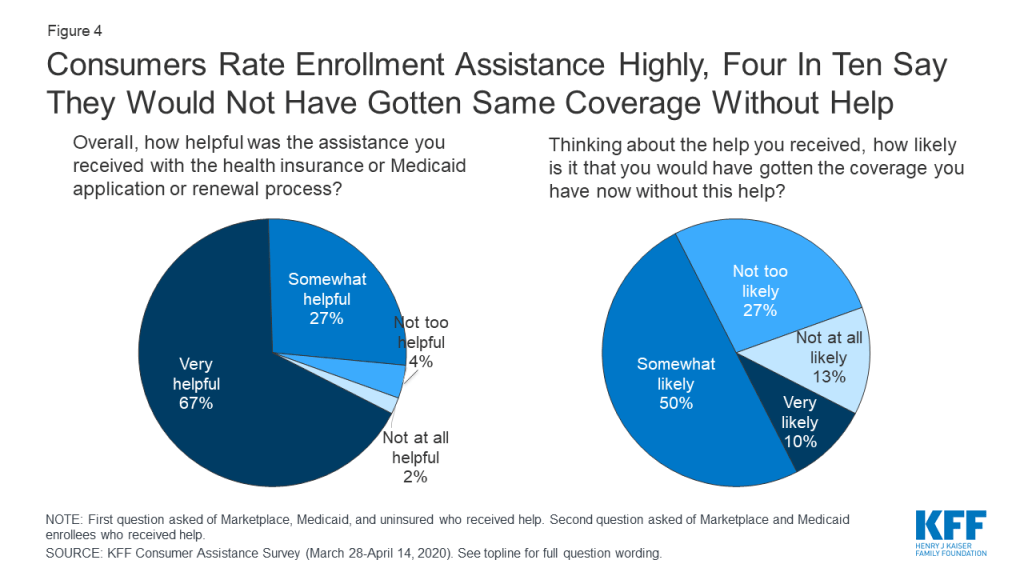

- Nearly one in five (18%) consumers who looked for coverage or actively renewed their coverage, or about seven million people, received consumer assistance in the past year. Most who enrolled in coverage with help said assistance made a difference; 40% think it is unlikely they would have found coverage without help.

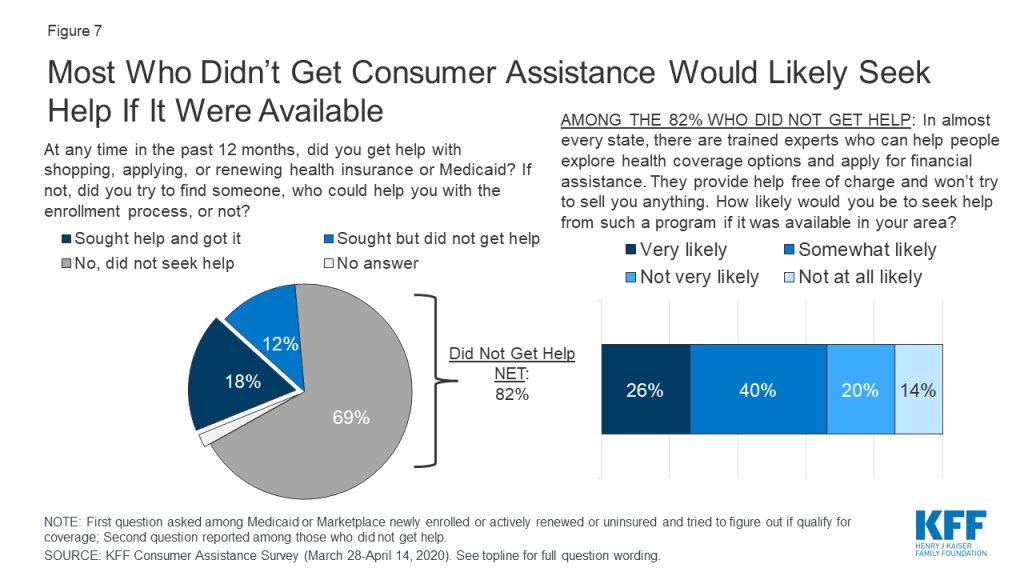

- Another 12% of target consumers—nearly five million people—tried to find help but did not get it, suggesting there is a shortage of consumer assistance. Among target consumers who were not helped in the past year, two-thirds said they would likely seek consumer assistance if it were available.

- Roughly one in four marketplace enrollees who were helped by a broker or commercial health plan representative said they were offered a non-ACA compliant policy as an alternative or supplement to a marketplace policy. Brokers and commercial health plan representatives rarely help with Medicaid enrollment.

- The COVID-19 pandemic could disrupt health coverage for potentially millions of people, but the findings suggest that public understanding of available coverage options and how to apply is limited. Most people who are uninsured or have marketplace of Medicaid coverage do not know or are unsure if the ACA has been overturned, if their state has expanded Medicaid eligibility, or time frames when they can apply. Consumer assistance could help people identify and navigate replacement coverage options.

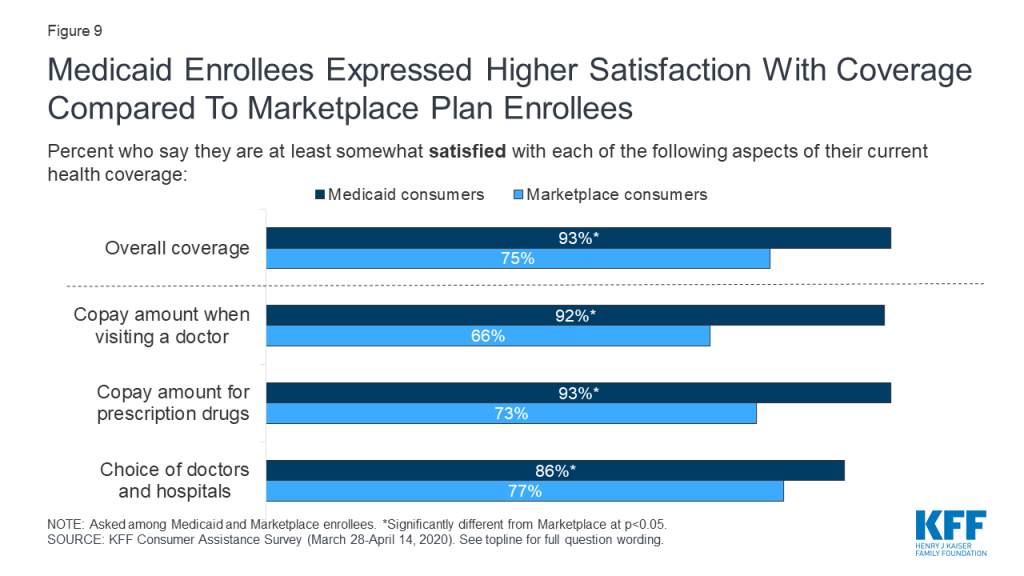

- Consumer satisfaction with marketplace plan coverage is generally high; satisfaction with Medicaid is even higher. Three-fourths of marketplace enrollees said, overall, they were very or somewhat satisfied with their plan coverage; among Medicaid enrollees, it was 93%. Medicaid enrollees were also significantly more satisfied with the level of cost sharing and with their choice of doctors and hospitals compared to marketplace enrollees.

Issue Brief

Introduction

Getting, keeping, and understanding health insurance has long been challenging for consumers. While most non-elderly Americans obtain health insurance through their employers, ten years after enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), many consumers without job-based coverage remain unsure of other coverage options or rules for applying. Many even struggle to understand basic health insurance terms and concepts. The ACA provided new, ongoing capacity for professional consumer assistance to help individuals get and keep health insurance, educate the public about coverage options and financial assistance, and resolve consumer questions and insurance problems.

By law, the ACA marketplaces operated by states or the federal government must establish Navigator programs that work year round, including during annual open enrollment, to help consumers apply for coverage and financial assistance through the marketplace – a single, “no-wrong-door” application is used to determine eligibility for marketplace subsidies and for coverage under Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Navigators help consumers enroll in marketplace plans as well as Medicaid, and they also conduct outreach and public education and provide post-enrollment assistance. The marketplaces also certify, but do not finance, consumer assistance programs operated by nonprofit community organizations, community health centers, and others, collectively known as certified application counselor (CAC) programs. Health insurance agents and brokers, who are paid commissions by insurers for the policies they sell, also provide professional consumer assistance.

KFF surveys of consumer assister programs have found that millions of consumers turn to these professionals for help each year. The process of learning about health coverage options and applying for financial help can be complicated, and many people lack confidence to complete it on their own. KFF assister program surveys have found that while there is overlap in the services provided and people served by Navigators, CACs, and brokers, they are not interchangeable. Navigator programs, compared to CACs, tend to be more trained and resourced, and more likely to help consumers with complex applications. Brokers are less likely than marketplace assister programs to help consumers who are uninsured, or need help in another language, or who apply for Medicaid.

Since 2017, the Trump Administration reduced Navigator funding in 32 federal marketplace states by 84% on average, from $63 million to $10 million, and many counties now have no Navigator service. Other recent program changes included eliminating the requirement that Navigators maintain a physical presence in the area they serve. The Administration also reduced funding for outreach/advertising during open enrollment by 90%. In explaining funding reductions, the Administration said consumers have grown more familiar with marketplace enrollment procedures, private health insurers have increased spending on outreach and advertising, and enrollment assistance from brokers is more cost efficient.

This report presents data from a March-April 2020 national survey of individuals who are most likely to use and benefit from consumer assistance with health insurance shopping or enrollment: those ages 18-64 who had coverage through marketplace policies (qualified health plans, or QHPs) or Medicaid or who were uninsured at the time of the survey. The survey asked respondents whether they received help applying for coverage in the past year, the nature of help received, and the reasons they sought help or not. The survey also asked respondents about their interest specifically in Navigator assistance, their awareness of financial help and marketplace rules, and their confidence in finding new coverage if they were to become unable to afford current coverage as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Who gets consumer assistance

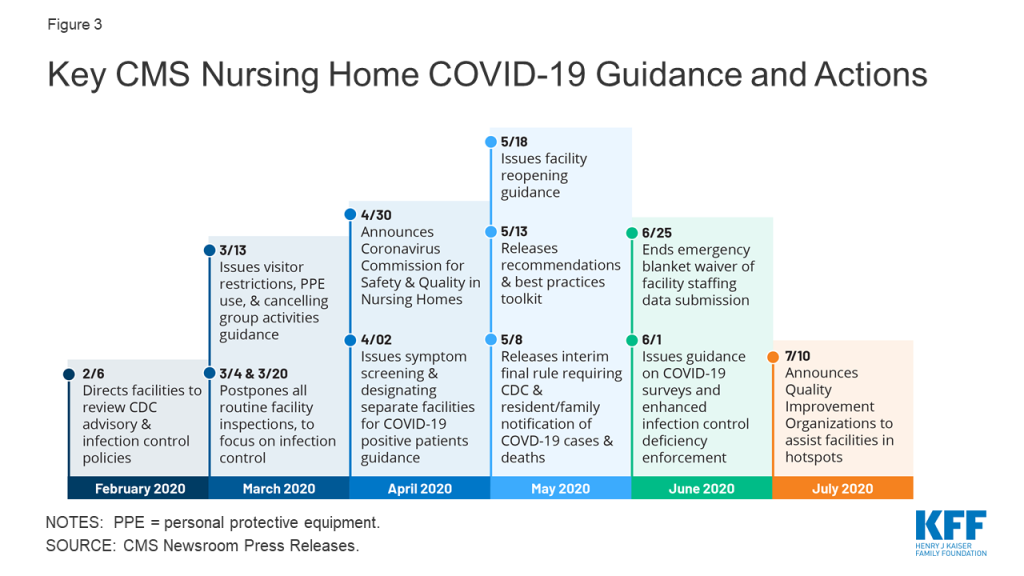

Overall, 18% of consumers with marketplace or Medicaid coverage or uninsured consumers who looked for coverage reported getting help from someone other than a friend or family member (Figure 1). We estimate this represents about seven million individuals who received consumer assistance in the past 12 months (see Methods section for description).

For the most part, there were few differences in demographic characteristics between consumers who got help and those who did not. Consumers who were newly applying for coverage were as likely to get or seek assistance as were those who actively renewed health plans (consumers enrolled in marketplace plans can actively renew their coverage by returning to the marketplace and looking for a new plan or, if they take no action, can be auto-renewed). Additionally, consumers sought help at about the same rate regardless of their age or income, or whether they lived in metropolitan or non-metro areas. Hispanic consumers were more likely to receive assistance than were White consumers. Hispanic consumers may be more likely to seek help because of language barriers or immigration concerns.

| Table 1: Share of Consumers Who Got Help or Sought Help with Health Plan Shopping or Renewal in the Past Year, by Key Demographics | |||||||||||||

| Among target consumers, percent who: | Race/Ethnicity | Income | Age | MSA | |||||||||

| White | Black | Hispanic | < 138% FPL | 138-249% FPL | 250-399% FPL | 400%+ FPL | 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | Metro area | Non-metro area | ||

| Got help with shopping, applying, or renewing health insurance or Medicaid from someone other than a family member or friend in the past 12 months | 16% | 18% | 23%* | 15% | 16% | 21% | 23% | 18% | 17% | 19% | 19% | 15% | |

| Did not get help in the last 12 months (NET) | 84 | 81 | 76 | 84 | 84 | 78 | 76 | 81 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 85 | |

| Tried to get help | 10 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 13 | |

| Did not try to get help | 72 | 71 | 63 | 71 | 72 | 67 | 64 | 67 | 72 | 68 | 69 | 73 | |

| Base: Newly enrolled or actively renewed Medicaid or Marketplace plan, or uninsured and tried to figure out if qualify for Medicaid or financial assistance in the past year* Indicates statistically significant difference between White and Hispanic groups (p<0.05) | |||||||||||||

Among consumers who renewed coverage this year without assistance, about one in five said they got help in a prior year when they first signed up for that coverage. Roughly a quarter (26%) of marketplace enrollees and one in five Medicaid enrollees who did not get help this year reported getting help when they first enrolled in their current coverage (Table 2).

| Table 2: One in five consumers with Marketplace or Medicaid coverage who were not helped this year received consumer assistance when they first signed up | |||

| Thinking back to when you first signed up for coverage, did someone other than a friend or family member help you with the process? | Insurance type | ||

| Total | Marketplace enrolled | Medicaid enrolled | |

| Yes | 22% | 26% | 20% |

| No | 67% | 67% | 67% |

| Not sure/Don’t remember/Refused | 12% | 8% | 13% |

| Base: Marketplace or Medicaid enrollees who did not received help in past 12 months | |||

Reasons consumers seek help

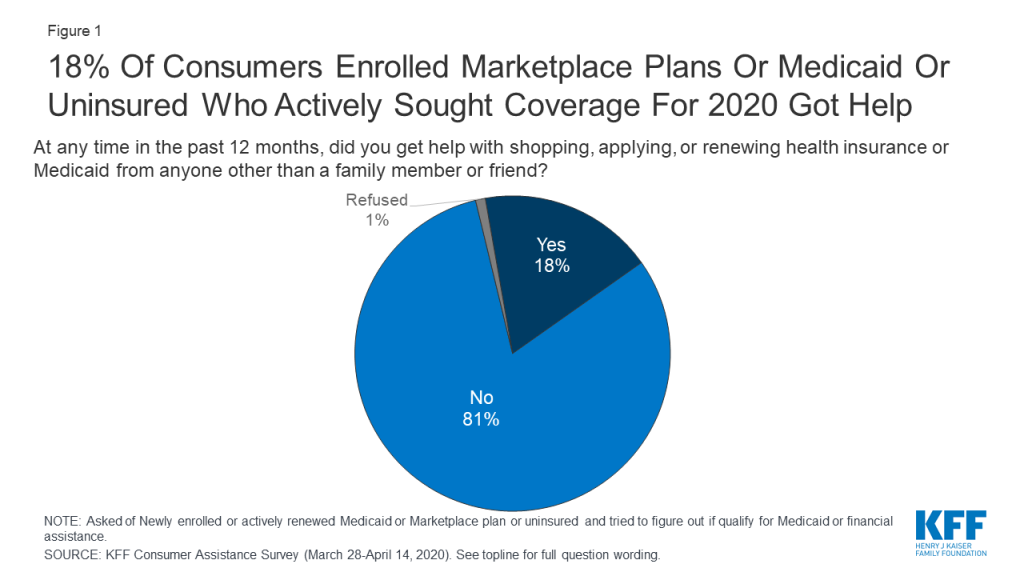

Consumers sought help for a variety of reasons, including lack of knowledge about coverage options and a complicated application process. Among consumers who received help 62% said they did not understand their coverage options and 52% said the process of applying was too complicated to complete on their own (Figure 2). Some consumers also sought help because they did not have internet access at home (18%), they had problems with the marketplace website (18%), or they needed assistance in Spanish (15%).

Consumers also reported challenges with multiple aspects of the application and plan selection process. Consumers applying for coverage and financial assistance must complete a multi-step process that typically begins with creating an online account. Those applying for financial assistance must report information about their income and household size; and are sometimes required to submit additional documentation by a deadline. Then consumers must review their plan options, including covered benefits, drug formularies, and provider networks and select one that best fits their needs. The process may vary somewhat depending on the type of coverage in which the person enrolls or whether they apply through the marketplace or through their state Medicaid agency. Each of these steps can pose challenges for consumers. Among uninsured adults who tried to find coverage, about eight in ten (83%) found at least one of these steps somewhat or very difficult. About six in ten (61%) consumers who enrolled in marketplace policies experienced difficulties. Consumers who enrolled in Medicaid were less likely to face challenges, though nearly four in ten found at least one step in the process somewhat or very difficult (Table 3).

| Table 3: Difficulties Faced by Consumers in Finding and Enrolling in Coverage | ||||

| Percent who say it was difficult to do each of the following when signing up/renewing/applying for a plan: | Insurance Type | |||

| Total | Marketplace enrollees | Medicaid enrollees | Uninsured, sought coverage | |

| Find a health plan to meet their needs | 28% | 38%* | 15% | 60%*^ |

| Compare your costs under different plans | 33 | 33 | N/A | N/A |

| Compare the doctors and hospitals they could see under each plan | 31 | 37* | 23 | 49* |

| Figure out if income qualifies them for financial assistance or Medicaid | 25 | 28* | 17 | 57*^ |

| Provide required documentation | 20 | 24* | 13 | 40*^ |

| Set up or access an online account | 19 | 22* | 16 | 29* |

| Understand and meet deadlines | 17 | 17* | 11 | 43*^ |

| Any of the above difficult | 51 | 61* | 38 | 83*^ |

| Base: Newly enrolled or actively renewed Medicaid or Marketplace plan, or uninsured and began an application for Medicaid or marketplace in the past year* Indicates statistically significant difference from Medicaid enrollees (p<0.05)^ Indicates statistically significant difference from Marketplace enrollees (p<0.05)N/A: only marketplace enrollees were asked about difficulty comparing costs under different plans | ||||

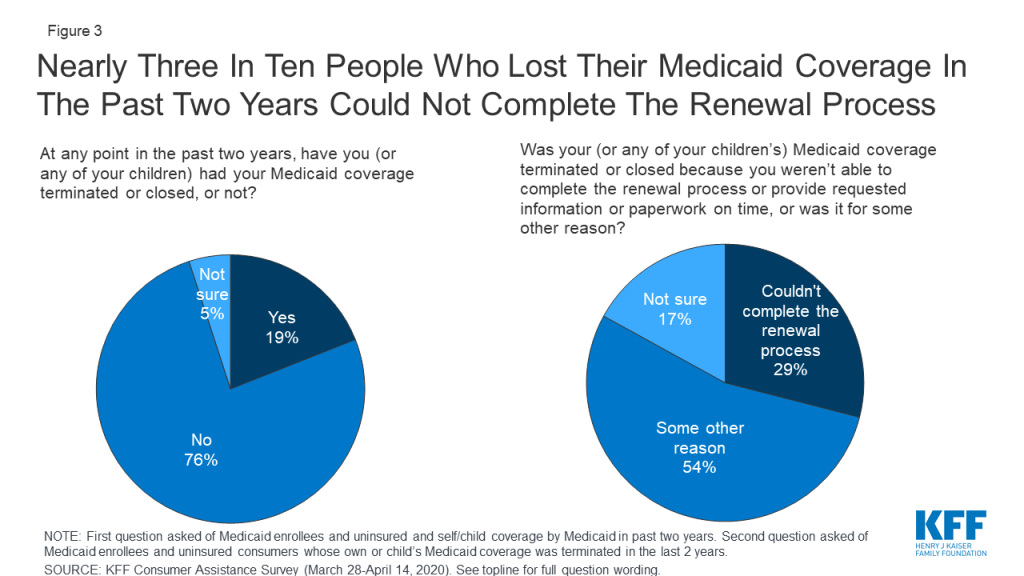

Some consumers struggled to complete the Medicaid renewal process. About one in five (19%) of those covered by Medicaid in the past two years said their or their child’s coverage was terminated at some point. While a relatively small share of current Medicaid consumers (11%) reported a coverage termination, a larger share (41%) of uninsured consumers who had been covered by Medicaid themselves or had a child covered by Medicaid said that coverage had been terminated. Among those whose Medicaid coverage had been terminated at some time in the past two years, nearly three in ten (29%) said it was because they could not complete the redetermination process (Figure 3). Until recently, many states had experienced a decline in Medicaid enrollment, due in part to increased use of periodic eligibility checks and redetermination requirements that the Trump Administration had encouraged. If individuals were unaware of the need to complete the redetermination process or were unable to complete the process within the required timeframe, their coverage would be terminated even if they remained eligible. However, since this survey was conducted, states have had to suspend most Medicaid terminations until the end of the COVID-19 emergency period in return for receiving enhanced federal Medicaid matching funding.

Measures of the benefits of consumer assistance

Consumers valued help they received and many questioned whether they would have obtained coverage without assistance. Overall, 94% of consumers who got assistance said it was very or somewhat helpful. Four in ten consumers who got help enrolling in coverage said it was somewhat or very unlikely they would have gotten their coverage without help; 50% said it was somewhat likely they would have gotten coverage (Figure 4). In addition, 27% of consumers who received help enrolling said they returned to their assister with help for other post-enrollment questions, such as help understanding how to use their new insurance.

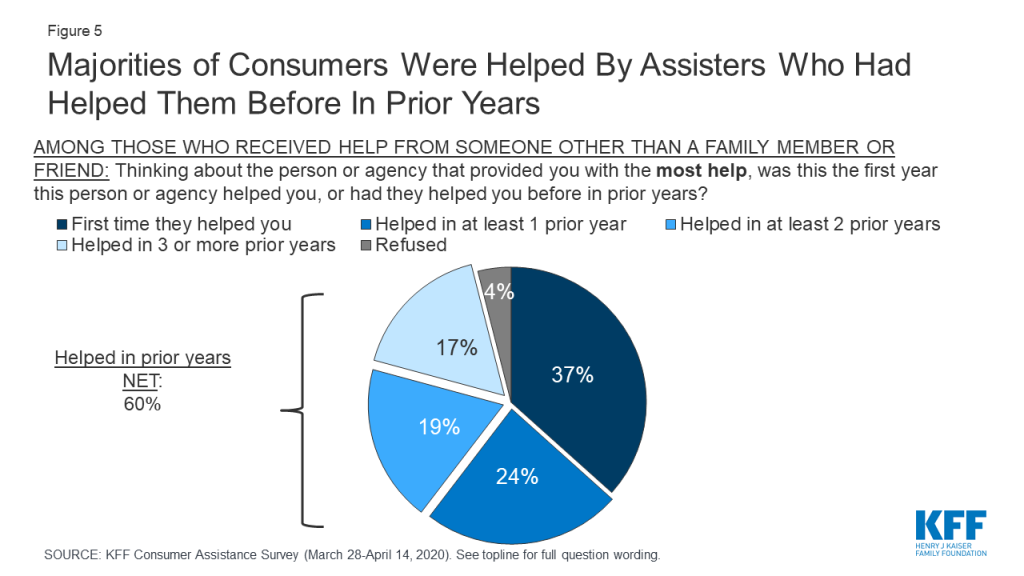

Many consumers sought help from the same assisters in previous years. Another indication of how consumers value enrollment assistance is the rate at which they return to assisters for help year after year. Most who received consumer assistance (60%) this year returned to someone who had helped them in the past, with 36% reporting they had been helped in two or more prior years by the person or agency who helped them this year (Figure 5).

Who provides consumer assistance

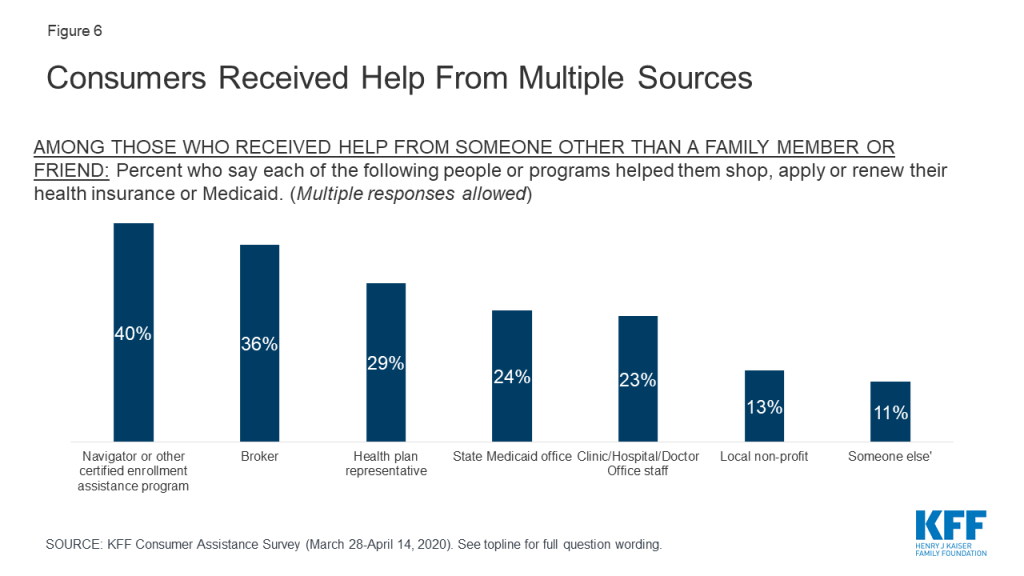

Consumers received help from a variety of sources, and often from multiple sources. A variety of entities provide consumer assistance, including Navigators, health insurance brokers, representatives from health plans, staff from health clinics, doctor’s offices, or hospitals, and community-based non-profits. People applying for Medicaid can also apply at state or local Medicaid offices. For consumers, identifying Navigator programs as such can be a challenge. In only in a handful of states is the Navigator program specifically branded – e.g. the NC Navigator Consortium in North Carolina. Navigator programs in most states are housed in community-based non-profits or in health clinics or hospitals; however, non-Navigator CAC programs also tend to be offered by non-profits, clinics, and hospitals. The Find Local Help Link in healthcare.gov does not distinguish Navigators from other CAC assister programs, although it does clearly identify brokers. According to the survey, among consumers who received assistance, 42% said they got help from more than one source. Including all sources of help, four in ten consumers who got help reported getting help from a Navigator, 36% said they got help from a broker, and 29% received help from a health plan representative. Fewer received help from a state Medicaid office or from a health care provider (Figure 6).

Consumers most frequently cited marketplace websites and word of mouth as the ways they learned about the person or organization that provided the help. About four in ten (42%) consumers who got help said they found assistance through a state or federal marketplace websites and 39% relied on word of mouth. Three in ten said they learned about assistance from a Medicaid office, and about one in five said the received a call or email from person or organization that helped them (21%) or heard about help through an advertisement or news coverage (18%). Fewer consumers cited outreach events (15%) or social media (6%).

Brokers provided assistance primarily to marketplace enrollees. Fourteen percent of marketplace enrollees overall reported receiving assistance from brokers compared to just 2% of Medicaid enrollees and 4% of people who were uninsured and sought coverage (Table 4). At the same time, both Medicaid enrollees and people who were uninsured were more likely than marketplace enrollees to have gotten help from a state Medicaid agency. Navigators helped consumers at about the same rate whether they were uninsured or enrolling in marketplace coverage or Medicaid.

| Table 4: Sources of Consumer Assistance, by Coverage Status | ||||

| Percent who say they received help from each of the following sources: | Insurance Type | |||

| Total | Marketplace enrollees | Medicaid enrollees | Uninsured, sought coverage | |

| Any source other than family member or friend | 18% | 21% | 15% | 20% |

| Navigator | 7 | 9 | 5 | 9 |

| Broker | 6 | 14* | 2 | 4 |

| Health plan representative | 5 | 6 | 3 | 9* |

| State Medicaid office | 4 | 1 | 6^ | 6^ |

| Clinic, hospital, or physician office staff | 4 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| Local non-profit | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Base: Newly enrolled or actively renewed Medicaid or Marketplace plan, or uninsured and tried to figure out if qualify for Medicaid or financial assistance in the past year. Multiple responses allowed.* Indicates statistically significant difference from Medicaid enrollees (p<0.05)^ Indicates statistically significant difference from Marketplace enrollees (p<0.05) | ||||

Some people helped by brokers or health plan representatives or who bought their coverage directly from a web broker or insurer web site were offered non-ACA compliant products. The Trump Administration has encouraged the use of brokers as a replacement for Navigators, and promoted enrollment in marketplace QHPs via health insurer and commercial web broker sites, called enhanced direct enrollment (EDE) sites, instead of healthcare.gov. About one in five (22%) marketplace enrollees who were helped by brokers or plan representatives or who enrolled through EDEs say they were offered an alternative to QHPs, such as short-term policies with lower premiums that exclude pre-existing conditions and other benefits required of ACA-compliant plans (Table 5). One-quarter said they were offered other noncompliant policies, such as cancer policies or hospital indemnity policies, to buy as a supplement to marketplace coverage. Additionally, 81% of marketplace enrollees who signed up through EDE sites or who were assisted by brokers or health plan representatives said that the person or site recommended a specific policy that would be best for that consumer. By contrast, Navigators and certified application counselors are prohibited from recommending non-ACA compliant policies and are required to provide only objective information.

| Table 5: Experiences of Marketplace Enrollees Helped by Brokers and Health Plan Representatives or who Bought Coverage on a Web Broker or Health Plan Web Site | ||

| When you chose or renewed your current plan, did the broker/web broker/health plan representative…? | Marketplace Enrollees | |

| Show you plans you could buy instead of a marketplace policy, such as short-term health plans | Yes | 22% |

| No | 59% | |

| Unsure | 19% | |

| Show you plans to buy in addition to a marketplace policy, such as policies that cover deductibles, pay daily cash benefits while in the hospital, or cover a single condition like cancer? | Yes | 25% |

| No | 59% | |

| Unsure | 16% | |

| Recommend a specific policy that would be best for you | Yes | 81% |

| No | 19% | |

| Unsure | 1% | |

| Base: Marketplace enrollees who got help from a health insurance broker or health plan representative, or who purchased health insurance from a broker, directly from an insurance company, or from a website offering plans sold by multiple insurance companies. | ||

More were interested in consumer assistance than got it

Among people who actively looked for QHP or Medicaid coverage in the past year, more expressed interest in consumer assistance than received it. Of consumers who actively looked for coverage, 12%, or nearly 5 million consumers, tried to find enrollment assistance without success.

Consumers who looked for help but did not get it cited various reasons, mostly stemming from limited availability of in-person assistance. About one-third (32%) of consumers who wanted but did not get help said they could not find help close to home, and another three in ten said they could not get an appointment (Table 6). One in ten reported they were unable to get help in Spanish. These barriers reflect actions that many Navigator programs said they would need to take in response to federal funding reductions – including cuts in staff, advertising, and services for non-English speaking consumers. Consumers with QHP coverage in federal marketplace states were less likely to be helped by Navigators (6%) compared to QHP enrollees in state-run marketplace states (18%), — suggesting that federal funding cuts and other changes to Navigator programs may have reduced access to these assisters relative to state-based marketplaces that maintained consumer assistance.

| Table 6: Reasons Why People Who Sought Consumer Assistance Didn’t Get it | |

| Among those who say they did not get help in the past year, but sought help, percent who say each of the following is the reason they did not get help: | |

| Couldn’t find help close enough to your home | 32% |

| Couldn’t get an appointment | 30 |

| Couldn’t find help in person and weren’t comfortable getting help over the phone | 26 |

| Couldn’t find help available in Spanish | 10 |

| Other reasons | 9 |

| Base: Those who did not get help with health insurance shopping, applying, or renewing in the past year, but tried to find someone to help them. Multiple responses allowed. | |

In addition, most consumers who did not get help said they would likely seek consumer assistance if it were available. When asked if they would be interested in receiving marketplace assistance from trained experts who would help them, free of charge, to explore coverage options and apply for financial assistance, two-thirds of consumers who did not receive any consumer assistance said they would likely seek help from such a program if it were available in their area (Figure 7). Lack of awareness is likely a key barrier to obtaining in-person assistance. Although the ACA requires all marketplaces to provide Navigator programs, that a majority of consumers who were not helped said they would likely seek help from such a program if it were available suggests that many do not know if these programs are available or how to find them.

Seven in ten people who actively looked for health coverage in the past year did not receive consumer assistance and did not try to find it. The most frequently offered reason for not seeking help is that they did not feel they needed help (67%). The perceived need for help varied by coverage status. People enrolled in marketplace plans were more likely to say they did not need help compared to Medicaid enrollees and uninsured individuals who looked for coverage (79% vs. 67% and 56%, respectively). Other reasons for not seeking help included not knowing where to look for help (29%) or not having time to look for help (19%) (Table 7). In addition, as noted earlier, 26% of marketplace enrollees and one in five Medicaid enrollees who did not get help this year reported getting help when they first enrolled in their current coverage.

| Table 7: Reasons why Consumers did not Seek Enrollment Assistance | ||||

| Percent who say each of the following is the reason for not seeking consumer assistance: | Insurance Type | |||

| Total | Marketplace enrollees | Medicaid enrollees | Uninsured, sought coverage | |

| You didn’t feel you needed help | 67% | 79%* | 67% | 56% |

| You didn’t know where to look for help | 29 | 27 | 28 | 33 |

| You didn’t have time to look for help | 19 | 19 | 18 | 19 |

| Other | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Base: Newly enrolled or actively renewed Medicaid or Marketplace plan or uninsured and tried to figure out if qualify for Medicaid or financial assistance, did not get help and did not try to find someone to help. Multiple responses allowed.* Indicates statistically significant difference from Medicaid enrollees and Uninsured, sought coverage (p<0.05) | ||||

Consumer assistance during the coronavirus pandemic

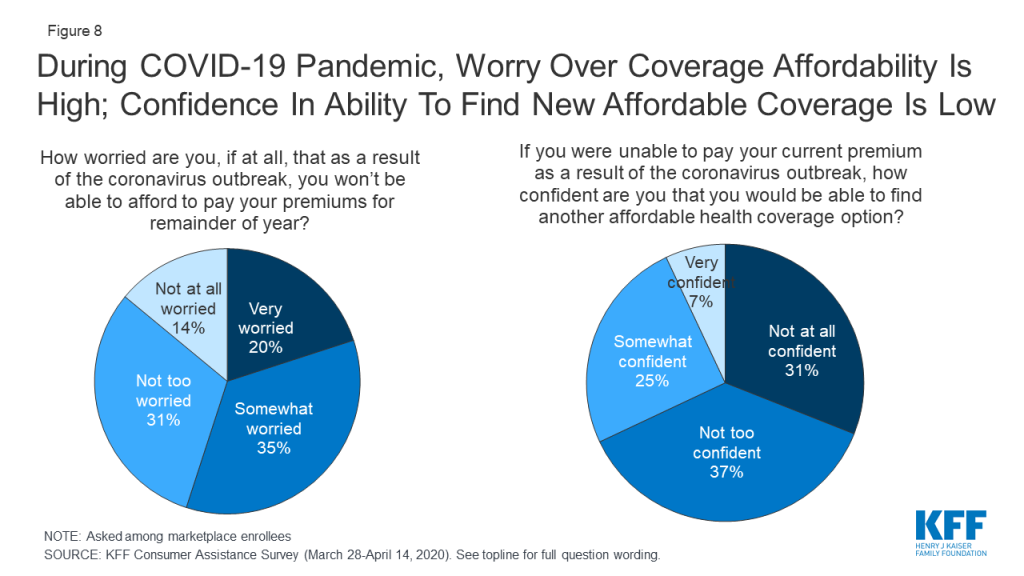

The coronavirus pandemic has caused many to lose their jobs and worry about maintaining their health coverage. The KFF consumer assistance survey was fielded March 28-April 14, 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic was emerging in the U.S. By mid-April, about 600,000 COVID-19 cases had been confirmed, compared to about five million cases today. Among people then enrolled in marketplace coverage, about half (55%) said they worried they would not be able to afford paying their premiums for the rest of this year due to the pandemic (Figure 8). Two-thirds (67%) said that if they were to lose current coverage as a result of the outbreak, they were not confident they would be able to find other coverage they could afford.

Many people have lost their job-based coverage because of the pandemic, but may not be aware of other coverage options. At the time the survey was conducted, 6% of those who were uninsured said they had recently lost health coverage due to the pandemic. Since then, KFF analysis estimates 26.8 million people who lost jobs as of early May are also at risk of losing their health benefits. While most of them would be eligible for other subsidized coverage through the marketplace or Medicaid, whether they can identify and enroll in new coverage for which they are eligible is another question. As noted earlier, about half of consumers experience difficulty with some aspect of the process of searching or applying for marketplace or Medicaid coverage. And even before the pandemic, nearly six in ten uninsured people were eligible for subsidized coverage under the ACA but not enrolled.

Many people lack basic information about the ACA and available coverage options. About a third (32%) of people correctly said the ACA is still the law; the rest were unsure or thought the law has been overturned (Table 8). While about half (48%) of people knew that marketplace enrollment is generally available only during open enrollment, fewer than four in ten (38%) were aware that Medicaid enrollment is available year-round. In addition, only one in five people knew whether their state had expanded Medicaid.

| Table 8: Consumer Awareness of Affordable Care Act Policies | ||||

| Percent who correctly say each of the following is true: | Insurance Type | |||

| Total | Marketplace enrollees | Medicaid enrollees | Uninsured | |

| The Affordable Care Act is still law. | 32% | 56%*^ | 30%^ | 22% |

| The individual mandate is no longer in effect for people who did not have coverage in 2019. | 39 | 52 *^ | 24 | 44* |

| There is a specific time period each year when most people need to sign up for a private health insurance plan through the ACA marketplaces. | 48 | 76*^ | 37 | 43 |

| People who are eligible for Medicaid can sign up at any time. | 38 | 31 | 49 ŧ^ | 33 |

| Among those in states that have expanded Medicaid | ||||

| Total | Marketplace enrollees | Medicaid enrollees | Uninsured | |

| Percent who correctly say that their state has expanded Medicaid programs to cover more low-income people | 21 | 26^ | 24^ | 14 |

| Among those in states that have not expanded Medicaid | ||||

| Total | Marketplace enrollees | Medicaid enrollees | Uninsured | |

| Percent who correctly say that their state has not expanded Medicaid programs to cover more low-income people | 21 | 27*^ | 19 | 20 |

| * Indicates statistically significant difference from Medicaid enrollees (p<0.05)^ Indicates statistically significant difference from Uninsured (p<0.05)ŧ Indicates statistically significant difference from Marketplace enrollees (p<0.05) | ||||

Consumer satisfaction with coverage

In general, consumers enrolled in marketplace plans or Medicaid expressed satisfaction with their coverage, with Medicaid enrollees expressing even higher levels of satisfaction. Three-fourths of marketplace enrollees said, overall, they were very or somewhat satisfied with their plan coverage; among Medicaid enrollees, it was 93% (Figure 9). Medicaid enrollees were significantly more likely than marketplace enrollees to say they were very or somewhat satisfied with copays or other out-of-pocket costs they face when they visit a doctor (92% vs. 66%) or when they fill a prescription (93% vs. 73%). Medicaid enrollees were also more likely than marketplace enrollees to express satisfaction with their choice of doctors and hospitals (86% vs. 77%).

Marketplace enrollees were less satisfied with the premiums they pay for coverage and with the annual deductibles associated with their plans. While Medicaid generally does not require enrollees to pay monthly premiums and does not have annual deductibles, marketplace plans charge premiums and impose deductibles and, even after accounting for subsidies, many enrollees find these costs burdensome. About one-third (35%) of marketplace consumers said they were somewhat or very dissatisfied with their monthly premium amount, and about half (48%) were dissatisfied with their deductible.

Attitudes toward alternative coverage options

Perceptions of the cost of health coverage discourage many people who are uninsured from applying. Two-thirds of those who are uninsured cited the cost of coverage as the main reason why they did not have health insurance. In part because of the perceived cost of insurance, just 29% of uninsured individuals said they tried to find coverage in the past year, and only one-third of those individuals (10% of all who were uninsured) completed an application. About half (54%) of uninsured consumers reported they have lacked coverage for two years or longer.

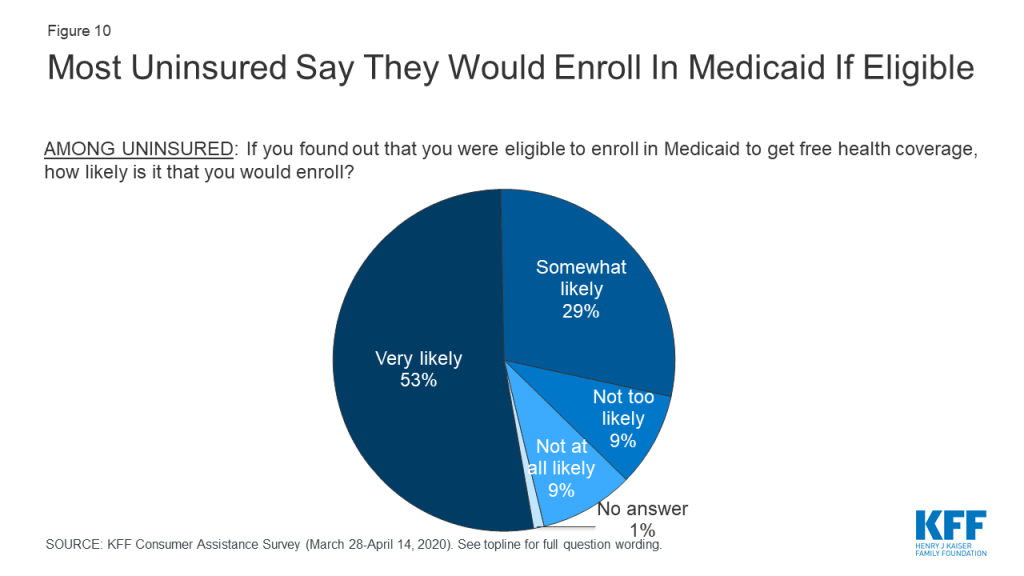

Eight in ten people who were uninsured said they would enroll in Medicaid if told they were eligible (Figure 10). Similar shares of uninsured people in states that had expanded Medicaid and in states that have not yet expanded responded they would enroll in Medicaid. These findings suggest that many uninsured residents in the 13 non-expansion states would enroll if their state expanded Medicaid. According to estimates, 24% of people who are uninsured are eligible for Medicaid, but are not enrolled. Lack of awareness of coverage options and barriers to enrollment may prevent those who are eligible from enrolling in coverage, pointing to the need for additional outreach and enrollment assistance.

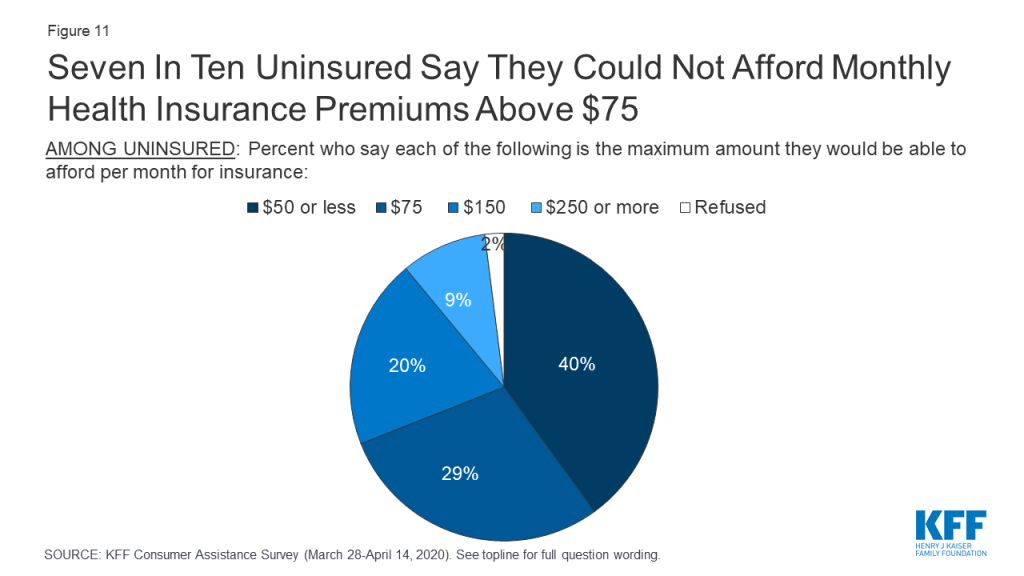

Most uninsured consumers cannot afford to pay a lot for health insurance. When uninsured individuals were asked what premium amount they could afford to pay for coverage each month, about seven in ten said $75 or less, with 24% saying even $50 would be unaffordable (Figure 11). In 2019, the average marketplace enrollee paid a premium of $87 after taking into account premium tax credits.

Most uninsured consumers do not want plans with high out-of-pocket costs. While 28% of the uninsured would qualify for “free” bronze premium this year because the premium tax credit would cover 100% of the monthly premium, 75% of uninsured individuals said they would not be interested in such a policy, whose annual deductible typically exceeds $5,000 per year.

Most marketplace and uninsured consumers would not purchase short-term, limited duration policies, but would be interested in enrolling in a public option. The Trump Administration has promoted other less expensive policies – such as short-term limited duration insurance – that can charge lower premiums because they exclude pre-existing conditions and limit covered benefits. However, about eight in ten (82%) marketplace and uninsured consumers said they would not purchase such a policy (Figure 12). By contrast, 72% of these consumers said they would be interested in a government-administered plan, or public option, as a source of coverage.

Discussion

Consumer assistance in health coverage matters. An estimated seven million people with marketplace or Medicaid coverage or who were uninsured and looked for coverage received consumer assistance. Nine in ten of those who received assistance rated it highly, and 40% of those who enrolled in coverage with assistance think it is unlikely they would have the same coverage today if not for help they received.

There is also evidence of a shortage of consumer assistance. An estimated five million consumers sought help but could not get it. Among consumers who did not receive help, 66% said they would likely seek consumer assistance if it were available. Resources to provide consumer assistance through the marketplace are limited and have been cut severely in recent years. Yet, the need for consumer assistance still appears to be large, with this survey finding about half who apply for coverage find at least some aspect of that process difficult. Also, consumers who are most likely to apply for marketplace coverage or Medicaid generally are not very familiar with coverage options or procedures. Most don’t know if the ACA remains law, or if their state has expanded Medicaid eligibility, or when during the year they can apply for these different types of coverage.

There is evidence brokers are not a substitute for marketplace consumer assistance programs. Brokers rarely help people apply for Medicaid. A significant share of consumers say brokers and web brokers recommend other non-ACA compliant coverage options, which may have lower premiums but also fewer protections.

During this pandemic, millions are at risk of losing their job-based coverage. While most will be eligible for replacement coverage through the marketplace or Medicaid, transitioning to these programs will not be intuitive or easy for many people. Greater availability of consumer assistance would help people losing employer-based insurance navigate their coverage options, but those options still could prove to be unaffordable for some.

This work was supported in part by the Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Methods

The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Consumer Assistance with Health Insurance Survey is based on interviews with a probability-based sample of 2,049 respondents between the ages of 18 and 64 who reported having health insurance purchased from a state or federal marketplace (the “Marketplace” group); being covered by Medicaid, excluding those who receive Supplemental Security Income (the “Medicaid” group); or not being covered by health insurance (the “Uninsured” group). Interviews were administered online from March 28 through April 14, 2020 in English and Spanish. The survey was designed and analyzed by researchers at KFF, and KFF paid for all costs associated with the survey.

Ipsos conducted sampling, interviewing, and tabulation for the survey using the KnowledgePanel, a representative panel of adults age 18 and over living in the United States. KnowledgePanel members are recruited through probability sampling methods using address-based sampling. Panel members who do not have internet access are provided with a netbook and internet service.

For this study, certain types of panelists were selected at disproportionately higher rates in order to allow for subgroup analysis, including those with Marketplace coverage, those living in states with state-based Marketplaces, those living in states that have not expanded Medicaid, and African Americans.

The combined results have been weighted to adjust for the fact that not all survey respondents were selected with the same probability, to address the implications of sample design, and to account for systematic nonresponse along known population parameters. In the first weighting stage, the sample of all respondents selected for the survey (prior to any termination due to ineligibility) was weighted to match the demographic makeup of the 18-64 year-old population by sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, household income, region, metro status, and language proficiency (for Spanish-speaking respondents). Demographic targets came from the Census Bureau’s 2018 Current Population Survey, except for language proficiency which was derived from the 2018 American Community Survey.

In the second weighting stage, eligible respondents were separated into 3 groups (Marketplace, Medicaid, and Uninsured), and the first stage weight was used to create demographic benchmarks for each group. Qualified respondents were then weighted to the resulting benchmarks.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total | 2,049 | ±3 percentage points |

| Marketplace | 731 | ±5 percentage points |

| Medicaid | 680 | ±5 percentage points |

| Uninsured | 638 | ±5 percentage points |

The estimates of the number of people helped and the number of people who sought help but did not get it were calculated by first estimating the universe for the target population, which is comprised of nonelderly adults enrolled in marketplace plans as of March 2020 who are in a new plan or actively renewed their 2019 plan; non-elderly who enrolled in Medicaid in the past year or actively renewed their Medicaid coverage, and who were not receiving SSI benefits as of that date; and nonelderly uninsured who actively sought coverage in the past year.

Marketplace enrollees. According to the Early 2020 Effectuated Enrollment Snapshot, 10.7 million people selected or were reenrolled in a marketplace plan as of March 15, 2020. In addition, based on data from the 2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Data, 880,000 adults enrolled in the Basic Health Plan (BHP) in New York and Minnesota for a total of 11.6 million marketplace and BHP enrollees. From the survey, 72% of marketplace enrollees are either in a new plan for 2020, or actively renewed their 2019 plan. Total marketplace enrollees newly enrolled or actively renewed in 2020 was 8.4 million.

Medicaid enrollees. Current Medicaid enrollment data that separate non-elderly, nondisabled adults are unavailable. Using 2018 data from a KFF analysis of Medicaid enrollees with disabilities, there are an estimated 25.5 million nonelderly, non-disabled adults on Medicaid. To include all the individuals helped, the children of adults on Medicaid were also included. According to the survey 47% of Medicaid enrollees reported one or more children was also enrolled in Medicaid at the time of the survey. Estimating one child per adult is about 12 million children. Total Medicaid enrollees in the sample universe was 37.5 million. This total was then reduced to include only those who enrolled in the past 12 months (20% from the survey or 7.5 million) or who actively renewed their coverage (39% from survey or 14.6 million) for a total of 22 million in the target population.

Uninsured individuals. Using data from 2018, there were 27.9 million nonelderly individuals without health coverage. According to the survey, 29% of people who were uninsured actively looked for coverage for a total of 8.1 million.

Summing the estimates results in 38.5 million people who could have been helped. According to the survey, 18% of people who could have been helped, actually got help or about 7 million people. Additionally, 12% of people who could have been helped sought help but didn’t get it or nearly 5 million people.