KFF Health Tracking Poll – July 2020

Coronavirus

Coronavirus: Reopening, Schools, And The Government Response

Key Findings

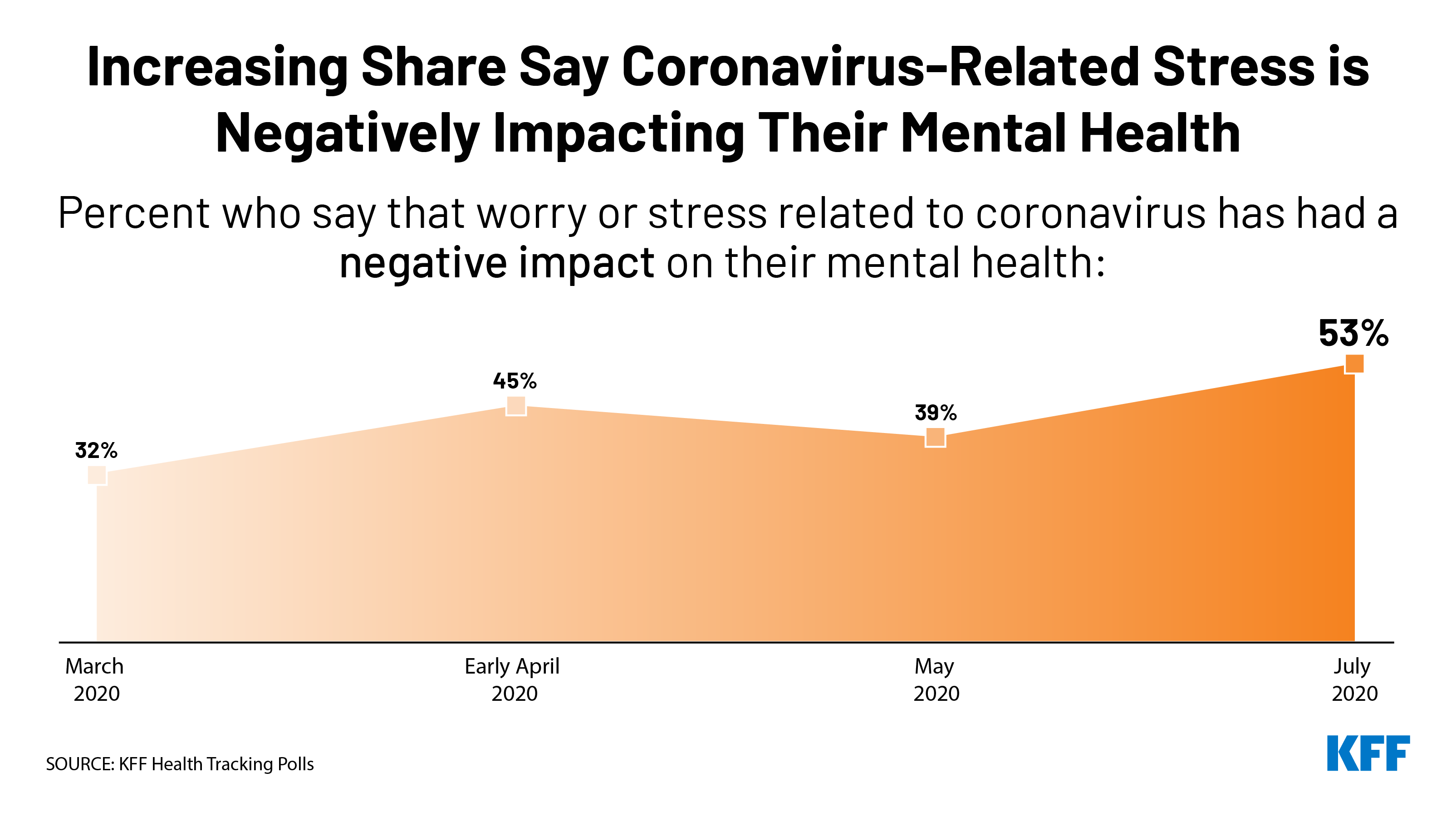

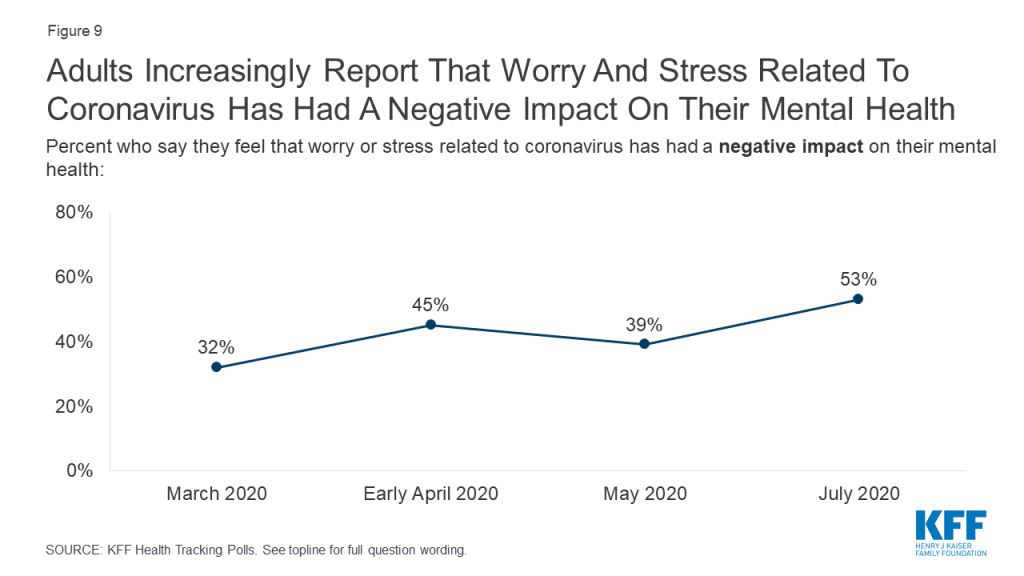

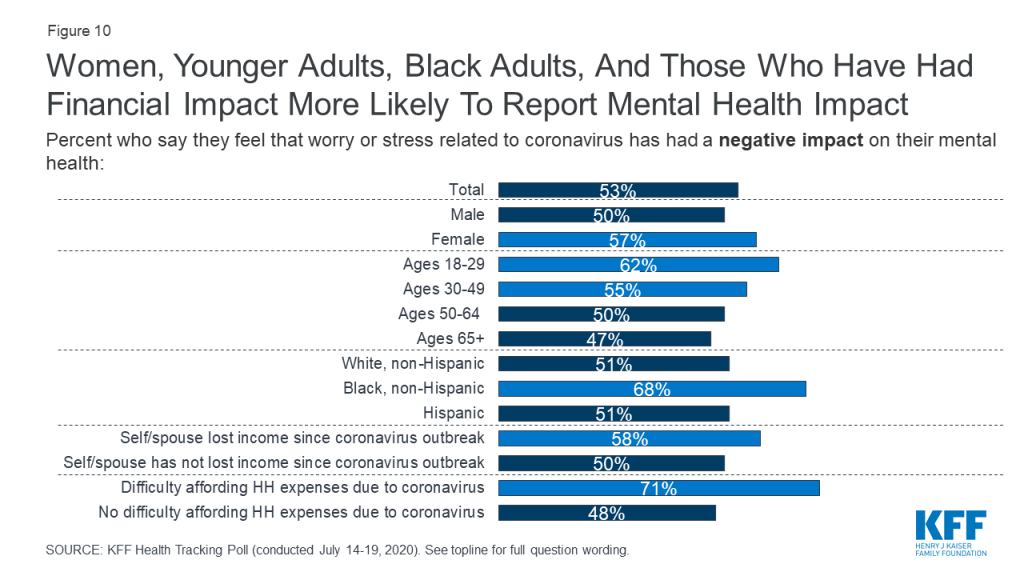

- Amid a surging coronavirus pandemic and record numbers of new cases in many states, the latest KFF Health Tracking Poll finds most U.S. adults feel the worst effects of the pandemic are yet to come, and seven in ten (including four in ten Republicans) rate the federal government response to the pandemic as fair or poor. The survey also indicates that the pandemic is increasingly taking an emotional toll, with a majority of U.S. adults (53%) saying that worry and stress related to coronavirus has had a negative impact on their mental health, up from 39% in May.

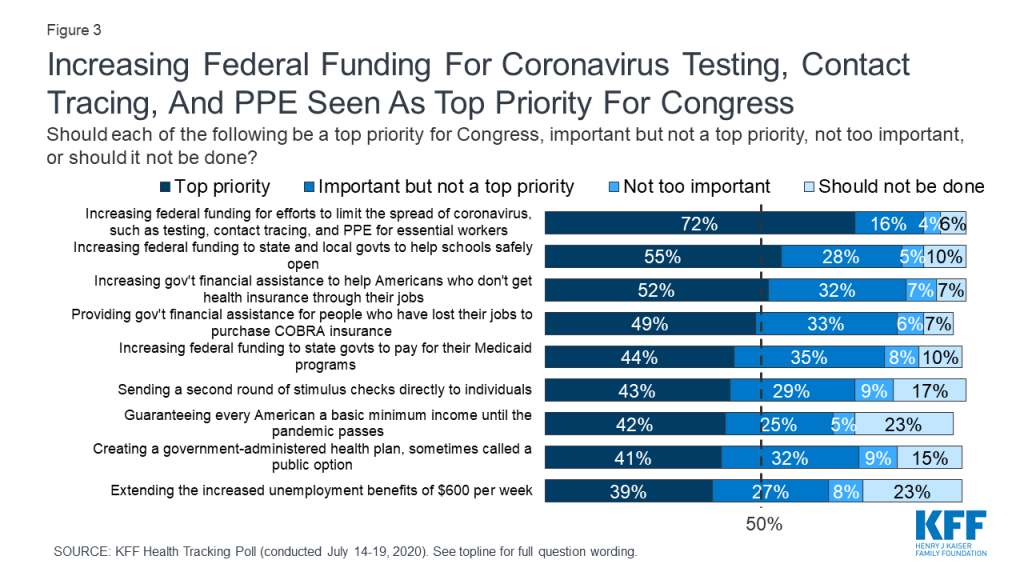

- With Congress set to consider its next coronavirus relief package, a clear majority of the public across political party affiliation says that top priority should be given to increasing federal funding for efforts to limit the spread of the virus such as testing, contact tracing, and personal protective equipment for essential workers. Most Democrats, and about half of independents and Republicans, also say Congress should prioritize increasing federal support for state and local governments to help schools reopen safely. Large shares of the public also see various measures to bolster individuals’ financial health and increase access to health insurance amid the economic downturn as important things for Congress to tackle, though partisans divide on the priority that should be placed on these measures.

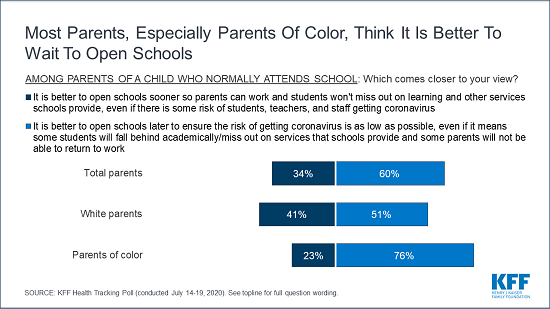

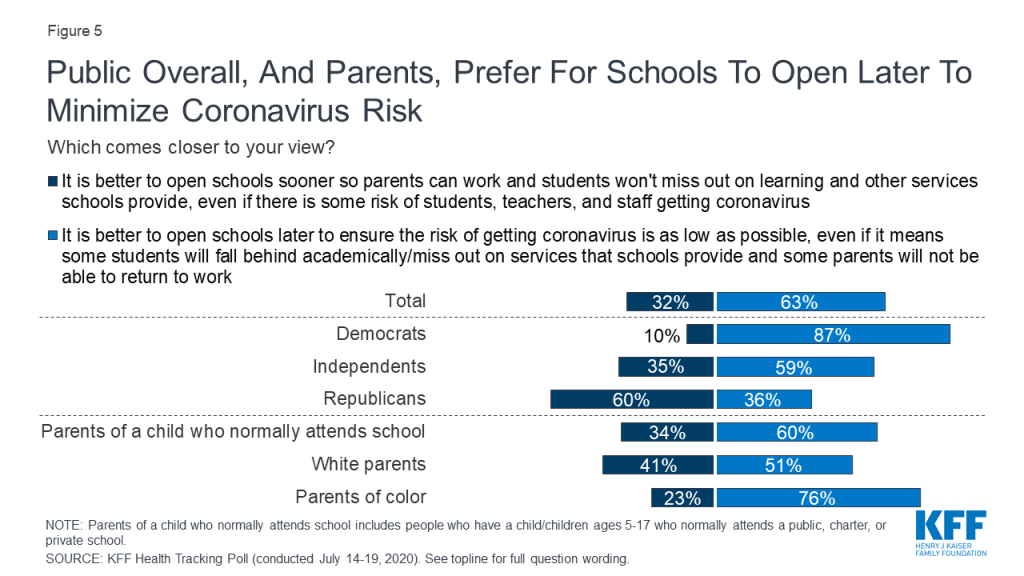

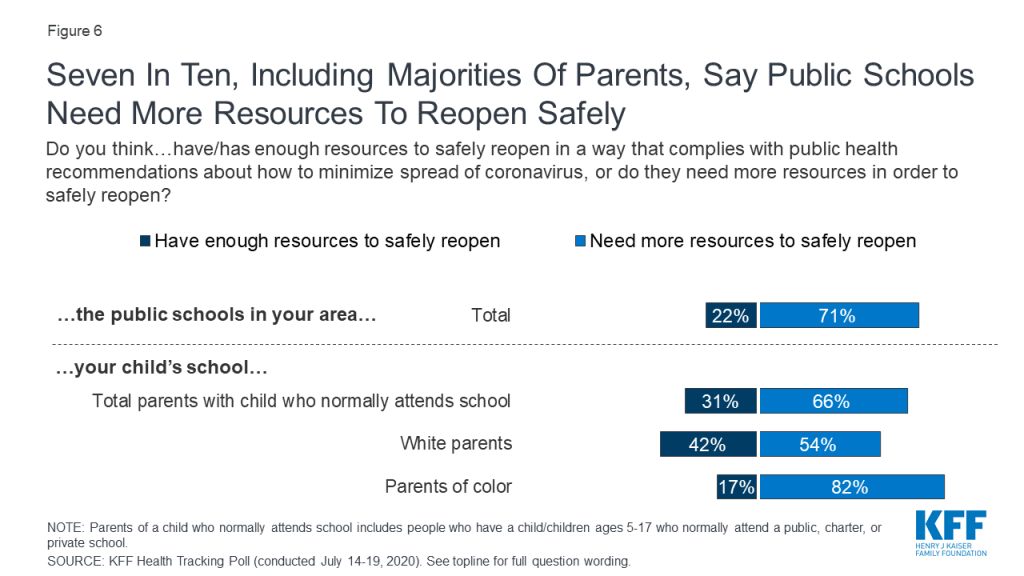

- With the new school year quickly approaching, the issue of whether and how to reopen schools looms large for both parents and policymakers. On balance, most parents with kids in school (60%) say it is better to open schools later to minimize infection risk, even if students miss out on academics and social services and some parents will not be able to work, while about half as many (34%) say it’s better to open schools sooner so parents can work and kids can get services, even if there’s some risk of infection. A majority (71%) of the public overall say that public schools in their area need more resources to reopen safely, and 66% of parents say the same about their own child’s school. Parents of color are more likely than White parents to say it is better for schools to open later to minimize infection risk, and to say that their own child’s school lacks the resources it needs to reopen safely.1

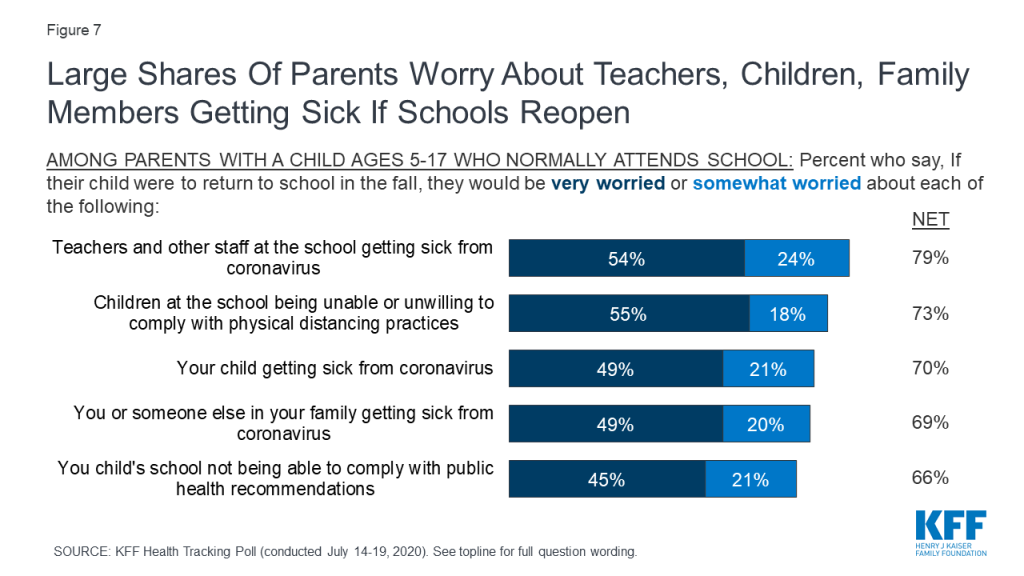

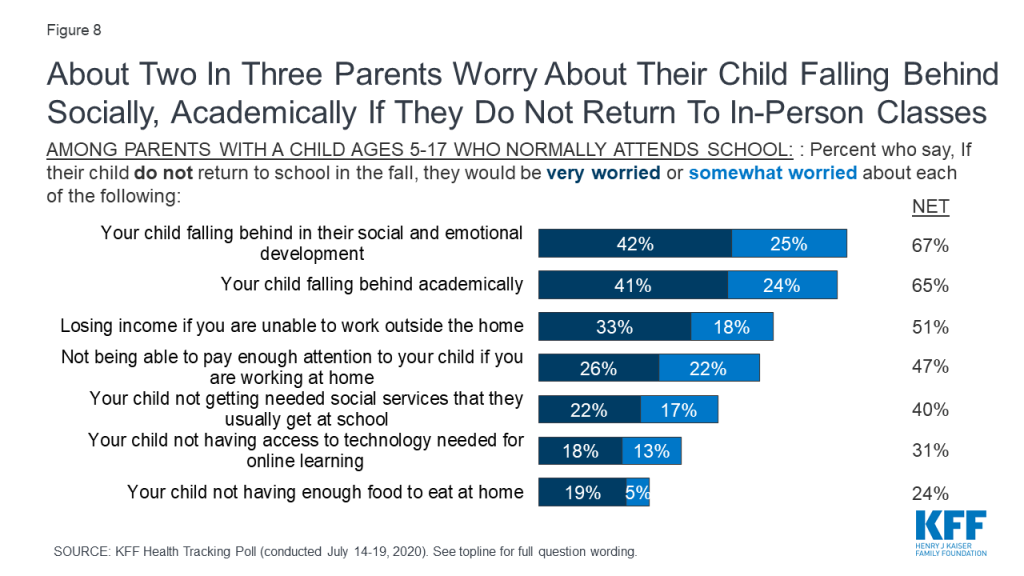

- Parents – particularly parents of color and those with lower incomes – have a variety of worries related to both a school reopening scenario, and one in which schools remain closed. When it comes to reopening, majorities are worried that their child, family members, or teachers may get sick from the virus, and most also worry about schools’ and students’ ability to comply with physical distancing and other public health guidance. If schools don’t reopen, about two-thirds of parents are worried about their children falling behind socially and emotionally (67%) and academically (65%), and about half worry about losing income if they can’t go to work (51%) or not being able to pay enough attention to their kids if they’re working at home (47%). The inability to access other services schools provide is a concern for some parents: 40% worry about their child not getting needed social services if schools remain closed, 31% worry they won’t have access to technology needed for online learning, and 24% worry about their children having enough food to eat at home. Many of these worries – both about the risks of school reopening and the loss of learning and social services – are much higher among parents of color and those with lower incomes than they are among White and higher-income parents.

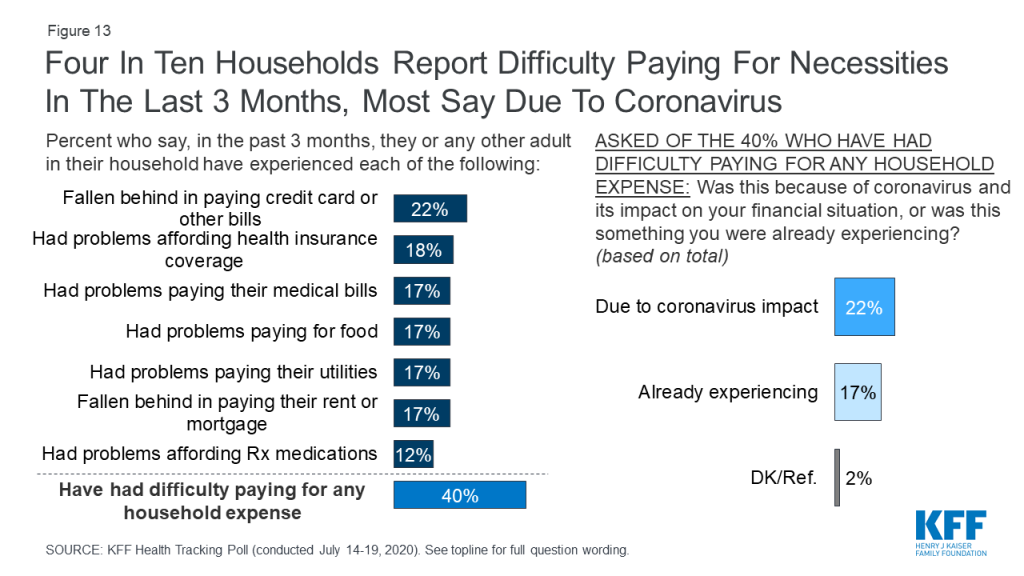

- The latest KFF Health Tracking Poll also finds that more than four months in, the coronavirus pandemic continues to take an economic toll on Americans. Four in ten report trouble affording basic necessities or falling behind on household or medical bills in the past 3 months, including 22% who say they experienced this directly because of coronavirus and its impact on their financial situation, and 17% who say they were experiencing these problems before coronavirus.

View On The State Of The Pandemic And Government Response

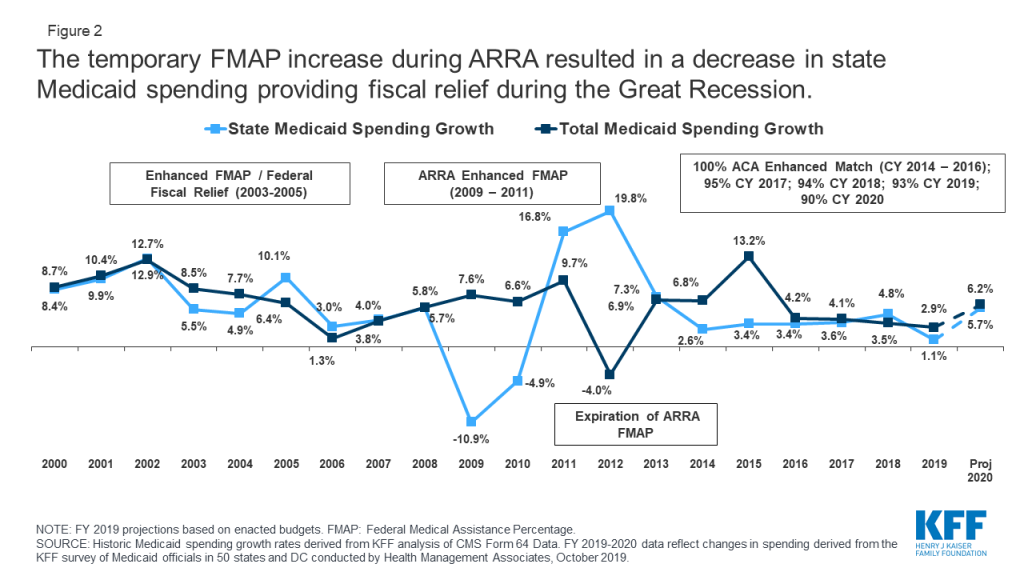

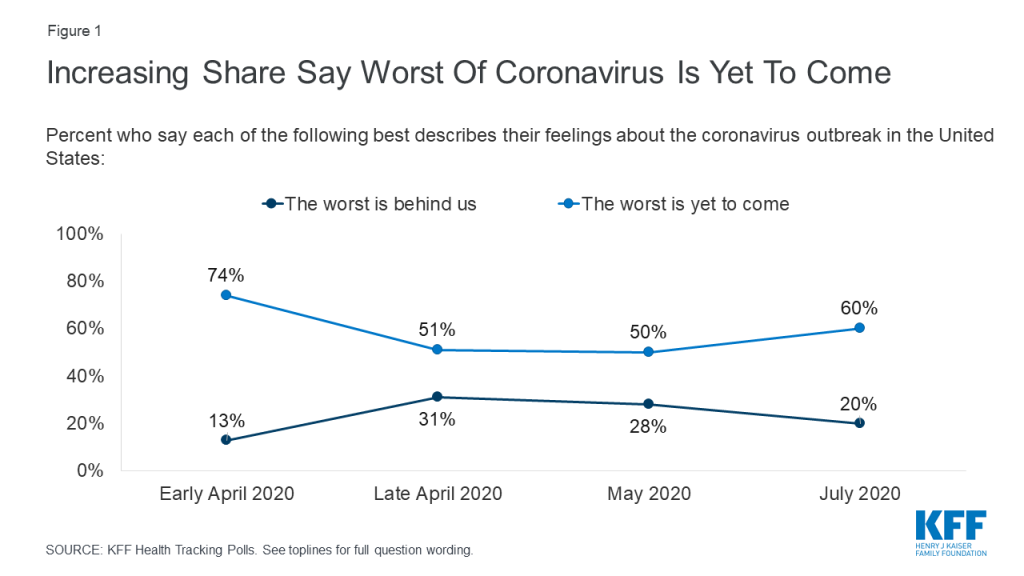

With a mounting death toll and coronavirus cases surging throughout much of the U.S., a majority of the public (60%) think that the worst is yet to come, up from 50% in May, though not as high as the 74% of adults in early April who thought things were likely to get worse. One in five adults (20%) currently think that the worst of the coronavirus outbreak is behind us. The overall numbers mask a deep partisan divide, with a slight majority of Republicans saying either “the worst is behind us” (31%) or that they don’t think the coronavirus is or will be a major problem (23%), while about eight in ten Democrats (79%) and a majority of independents (57%) say “the worst is yet to come.”

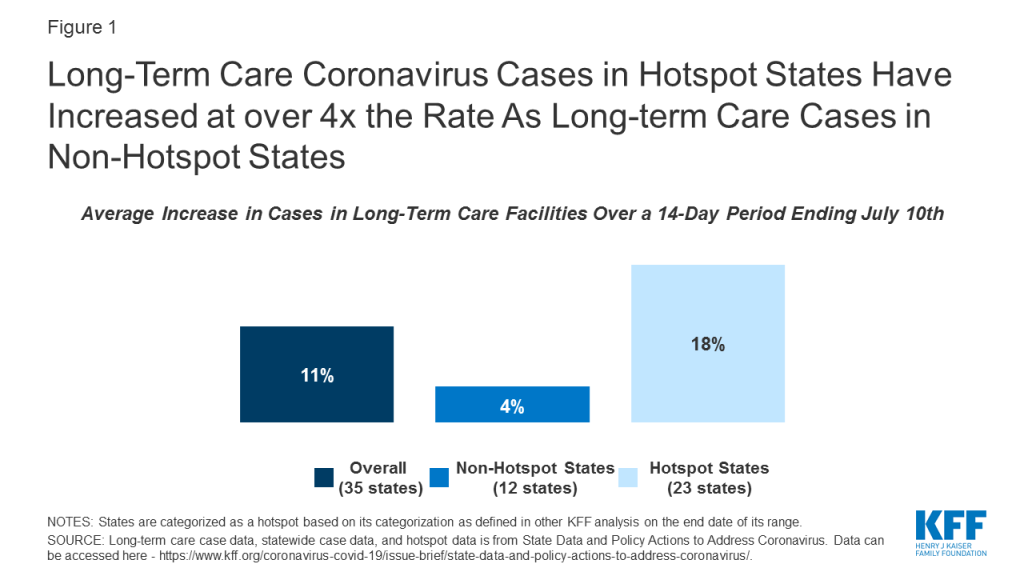

Amid what many see as a botched federal response to the virus, about half of U.S. adults (48%) rate the federal government response to the pandemic as “poor” while another 23% call it “fair.” Just 28% rate the federal response as “good” or “excellent.” Even among Republicans, who are generally supportive of President Trump and his Administration, 42% rate the federal government response to the pandemic as “fair” or “poor.” The public is more divided when it comes to assessing state and local governments, with about half of adults giving their state (46%) and local (48%) governments positive marks.

| Table 1: Views of federal, state, and local response to coronavirus by party identification | |||

| How would you rate…to the current coronavirus outbreak? | Party identification | ||

| Democrats | Independents | Republicans | |

| …the federal government’s response… | |||

| Excellent/good | 8% | 26% | 57% |

| Fair/poor | 91 | 73 | 42 |

| …your state government’s response… | |||

| Excellent/good | 55 | 42 | 44 |

| Fair/poor | 44 | 57 | 56 |

| …your local government’s response… | |||

| Excellent/good | 57 | 45 | 50 |

| Fair/poor | 42 | 54 | 47 |

Majorities Across Parties Say Congress Should Prioritize Funding For Testing And Contact Tracing

As Congress discusses its next coronavirus relief package, there are reports that the Trump Administration is resisting allocating additional federal funds for coronavirus testing, contact tracing, and other prevention measures. This is at clear odds with the public’s priorities; when asked about a number of potential actions Congress could take, the highest-ranked priority among the public is increasing federal funding for efforts to limit the spread of coronavirus, such as testing, contact tracing, and personal protective equipment for essential workers. Seven in ten adults overall (72%) say this should be a top priority for Congress, including majorities of Democrats, independents, and Republicans. Schools are another popular priority: a majority (55%) say increasing federal funding to state and local governments to help schools reopen safely should be a top priority, including about two-thirds of Democrats (68%) and about half of independents (53%) and Republicans (48%).

Other measures to provide economic relief or extend insurance benefits are seen as important by large shares of the public overall, but have less broad appeal across partisans. For example, about half the public overall say increasing government financial assistance to help Americans who do not get health insurance from their jobs pay for coverage (52%) and providing financial assistance for people who have lost their jobs to purchase COBRA insurance through their former employers (49%) should be top priorities. However, there are large partisan gaps, with Democrats 42 percentage points more likely than Republicans to say Congress should place a top priority on increasing government financial assistance for individual health insurance, and 26 percentage points more likely to say Congress should place a top priority on providing assistance for people to purchase COBRA coverage.

About four in ten overall say other actions should be top priorities for Congress, including increasing funding to states to help pay for Medicaid (44%), sending a second round of stimulus checks to individuals (43%), guaranteeing every American a basic income until the pandemic passes (42%), creating a public option health insurance plan (41%), and extending the additional unemployment benefits set to expire at the end of July (39%). Views on each of these measures are marked by large partisan differences, with about six in ten Democrats saying each should be a top priority, compared with about a quarter of Republicans.

| Table 2: Views of potential Congressional actions on coronavirus by party identification | |||

| Percent saying each of the following should be a “top priority” for Congress: | Party identification | ||

| Democrats | Independents | Republicans | |

| Increasing federal funding for efforts to limit the spread of coronavirus | 90% | 65% | 57% |

| Increasing federal funding to state and local governments to help schools safely open | 68 | 53 | 48 |

| Increasing government financial assistance to help more Americans who don’t get health insurance through their jobs purchase coverage | 73 | 49 | 31 |

| Providing government financial assistance for people who have lost their jobs to purchase COBRA health insurance | 63 | 47 | 37 |

| Increasing federal funding to state governments to help pay for their Medicaid programs | 63 | 43 | 25 |

| Sending a second round of stimulus checks directly to individuals | 58 | 40 | 27 |

| Guaranteeing every American a basic minimum income until the pandemic passes | 56 | 42 | 27 |

| Creating a public option health plan | 57 | 39 | 26 |

| Extending the increased unemployment benefits of $600 per week which are set to expire on July 31st | 59 | 36 | 25 |

Views On The Pace Of Reopening, Including Schools

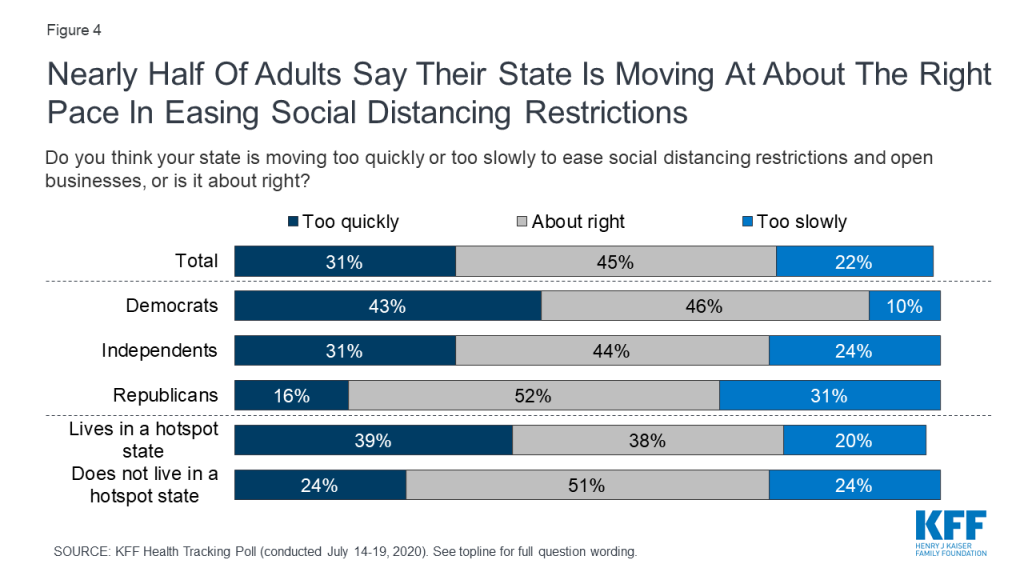

With coronavirus cases surging in many states that took an early approach to reopening, a plurality (45%) of adults overall say their state is moving at about the right pace in easing social distancing restrictions and opening businesses, while three in ten (31%) say their state is moving “too quickly” and about one in five (22%) say their state is opening “too slowly.” Views on reopening vary by both partisanship and location. Democrats are about three times as likely as Republicans to feel their state is moving too quickly, while Republicans are about three times as likely as Democrats to feel their state is moving too slowly. Notably, about four in ten adults (39%) in states that are current coronavirus hotspots (based on case data as of July 18) say their state is moving too quickly to reopen, compared to about one in four (24%) in non-hotspot states.2

Public And Parents Prefer To Delay School Openings To Mitigate Risk

With the new school year quickly approaching, the issue of whether and how to reopen schools for in-person instruction has been at the forefront of discussions for both parents and policymakers. President Trump has stated that he wants schools to reopen for in-person instruction in the fall, and has even suggested that the federal government may withhold money from schools that don’t reopen. When asked to weigh the risks vs. benefits, a majority of the public (63%) thinks it is better to open schools later to ensure the risk of getting coronavirus is as low as possible, even if it means some students will fall behind academically or miss out on services and some parents will be unable to return to work. About a third (32%) think it is better to open schools sooner so that parents can work and students won’t miss out on learning and other services, even if there is some risk to teachers, students and staff. There is a large partisan gap on this issue among the public overall, with 87% of Democrats and 59% of independents preferring schools open later while six in ten Republicans (60%) prefer that schools open sooner.

Among parents with a child age 5-17 that normally attends school, six in ten (60%) think it is better to reopen schools later in order to ensure the risk of coronavirus is as low as possible, while about half as many (34%) think it is better to reopen sooner. Parents of color (76%) are even more likely to prefer a later reopening compared to their White counterparts (51%).

The public’s caution towards reopening schools may be reinforced by a sense that schools do not have the necessary resources to safely reopen in a manner that complies with public health recommendations on how to minimize the risk of spreading coronavirus. Seven in ten adults overall say that public schools in their area need more resources in order to safely reopen, while just 22% say schools have enough resources. This sentiment is echoed by parents of school-aged children when they are asked about their own child’s school. Two-thirds of parents (66%) say their child’s school needs more resources in order to safely reopen. Notably, parents of color are more likely than their White counterparts to say their child’s school lacks the resources necessary to safely reopen (82% vs. 54%).

Parents – Particularly parents of color and those with Lower Incomes – Worry about both school reopening And remaining closed

With many schools’ academic year commencing in August and early September, about half of parents with children who typically attend school (52%) said their child’s school had not yet announced whether they would be having in-person classes this fall at the time they took the survey. This month’s poll asked parents about worries related to both a school reopening scenario and one in which schools remain closed to in-person instruction. When it comes to reopening, large shares of parents with a child enrolled in school are worried about teachers and staff getting sick from coronavirus (79% very or somewhat worried) and children being unable or unwilling to comply with physical distancing practices (73% very or somewhat worried). About seven in ten are also worried about their child (70%) or themselves or a family member (69%) getting sick from coronavirus, while two-thirds (66%) worry about their child’s school being unable to comply with public health recommendations.

Reflecting the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus pandemic on those with lower incomes and on communities of color, there are some notable differences in worry levels between parents of color and White parents, and between those with lower and those with higher household incomes. Nine in ten parents of color (91%) say they are either “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about their child getting sick with coronavirus if they return to school in the fall, compared to 55% of White parents who say the same. Similarly, about nine in ten of parents of color say they are worried about teachers and other staff getting sick with coronavirus (92%), children being unable or unwilling to physically distance (91%), and that they or a family member will get sick with coronavirus (90%). Far fewer White parents say they are worried about each of these concerns.

In addition, parents who have a household income under $90,000 are more likely than their higher-income counterparts to say they are worried about children being unable or unwilling to physically distance (82% vs. 62%) or teachers and staff getting sick from the coronavirus (84% vs. 73%).

| Table 3: Worries about school reopening among parents by race/ethnicity and household income | |||||

| Percent who say they are “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about each of the following if their child DOES return to school in-person: | All parents with a child who normally attends school | Race/ethnicity | Household Income | ||

| Parents of color | White Parents | Parents with HH income under $90,000 | Parents with HH income $90,000+ | ||

| Teachers and other staff at school getting sick from coronavirus | 79% | 92% | 69% | 84% | 73% |

| Children at the school being unable or unwilling to comply with physical distancing practices | 73 | 91 | 60 | 82 | 62 |

| Their child getting sick with coronavirus | 70 | 91 | 55 | 75 | 65 |

| They or someone else in their family getting sick from coronavirus | 69 | 90 | 53 | 72 | 66 |

| Their child’s school being unable to comply with public health recommendations | 66 | 88 | 49 | 68 | 66 |

Parents also express a number of worries related to schools remaining closed for in-person instruction in the fall. If schools don’t reopen, about two-thirds of parents say they would worry about their children falling behind socially and emotionally (67%) and academically (65%), and about half say they would worry about losing income if they can’t go to work (51%) or not being able to pay enough attention to their kids if they’re working at home (47%). Other services schools provide are also a concern for some parents: 40% worry about their child not getting needed social services if schools remain closed, 31% worry they won’t have access to technology needed for online learning, and 24% worry about their children having enough food to eat at home.

Similar to the findings on parental worries about their child returning to school in-person in the fall, parents of color and those with lower household incomes are also more likely than their counterparts to say they worry about possible outcomes if their children do not return to in-person classes.

Parents of color are more likely than White parents to say they are “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about their child not getting social services they usually get at school (52% vs. 32%), are almost three times as likely to worry their child won’t have access to the technology needed for online learning (49% vs. 17%), and about five times as likely to worry their child will not have enough to eat at home (44% vs. 9%). Parents of color are also more likely than White parents to worry about losing income if they are unable to work outside the home (65% vs. 41%).

Similarly, parents with household incomes under $90,000 more likely than their higher income counterparts to be worried that their child will not have access to social services they usually get at school (47% vs. 26%), will not have enough to eat at home (34% vs. 6%), or won’t have access to the technology needed for online learning (43% vs. 10%). Moreover, lower-income parents are more likely than those with higher incomes to worry about losing income if they are unable to work outside the home (61% vs. 35%).

| Table 4: Worries about schools remaining closed among parents by race/ethnicity and household income | |||||

| Percent saying they are “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about each of the following if their child DOES NOT return to school in-person: | All parents with a child who normally attends school | Race/ethnicity | Household Income | ||

| Parents of color | WhiteParents | Parents with HH income under $90,000 | Parents with HH income $90,000+ | ||

| Their child falling behind on their emotional and social development | 67% | 76% | 62% | 68% | 65% |

| Their child falling behind academically | 65 | 73 | 60 | 66 | 63 |

| Losing income if they are unable to work outside the home | 51 | 65 | 41 | 61 | 35 |

| Not being able to pay enough attention to their child if they are working from home | 47 | 56 | 41 | 49 | 48 |

| Their child not getting needed social services they usually get at school | 40 | 52 | 32 | 47 | 26 |

| Their child not having enough to eat at home | 24 | 44 | 9 | 34 | 6 |

| Their child not having access to the technology needed for online learning | 31 | 49 | 17 | 43 | 10 |

The Continuing Impact Of The Coronavirus Pandemic On Mental Health, Wellbeing, And Financial Health

over half report a negative impact on mental health

As life with the coronavirus pandemic wears on, Americans increasingly say it is taking a negative toll on their mental health. For the first time since KFF began tracking this question in March, a majority of adults (53%) now say that stress and worry related to the pandemic has had a negative impact on their mental health. This is up 14 percentage points since May, and up 8 percentage points since the previous high of 45% in early April. About one in four (26%) say worry and stress related to coronavirus has had a “major impact” on their mental health, while a similar share (28%) say it has had a “minor impact.”

Notably, younger adults are more likely older adults, and women are more likely than men, to say stress and worry related to coronavirus has had a negative impact on their mental health. About seven in ten Blacks adults (68%) and those who have had difficulty paying household bills in the past three months due to the financial impact of the coronavirus outbreak (71%) say that stress and worry related to the pandemic has had a negative impact on their mental health.

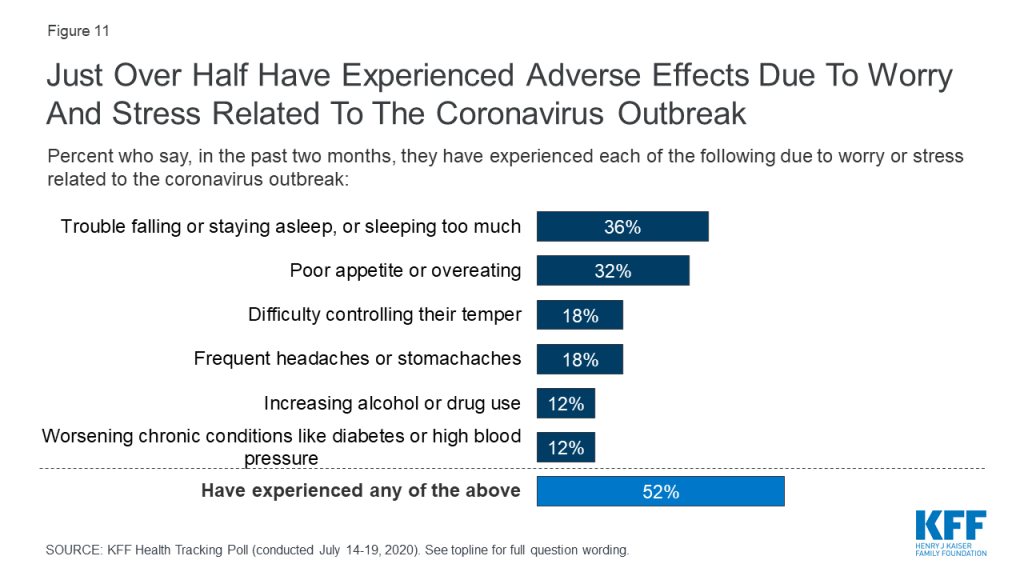

In addition to reporting a general negative impact on their mental health, about half (52%) of adults report that worry and stress related to the coronavirus outbreak has had adverse effects on their mental health and wellbeing in specific ways. About a third say coronavirus-related worry or stress has led to problems with their sleep (36%) or has led to a poor appetite or overeating (32%). About one in five say worry or stress related to the pandemic has caused them to experience frequent headaches or stomachaches (18%) or difficulty controlling their temper (18%), while 12% each say it has led to increased alcohol or drug use or worsening chronic health conditions.

Mirroring the findings on overall negative impact on mental health, younger adults and women are more likely than their counterparts to say coronavirus-related stress has caused adverse effects on their mental health or wellbeing. Notably, three in four adults who have had difficulty paying household bills in the past three months due to the financial impact of coronavirus say they have also experienced adverse effects their mental health and wellbeing, as do about six in ten Hispanic adults and Black adults.

four in ten have problems affording household expenses or health care

With the country facing a double-digit unemployment rate, four in ten adults say they or an adult in their household has had problems paying bills or difficulty affording medical care or basic expenses in the past three months. This includes about one in five who say they have fallen behind on their credit card bills (22%), 18% who have had trouble affording health insurance, and similar shares who say they have had trouble paying medical bills (17%), paying for food (17%), paying utility bills (17%) or have fallen behind on their rent or mortgage (17%). Additionally, 12% say they have had problems affording their prescription medications. Notably, among the 40% of adults who have experienced difficulty paying household or medical bills in the last three months, most (54%, or 22% of all adults) say it was due to the coronavirus outbreak and its impact on their financial situation, while 42% (17% of all adults) say this something they were already experiencing before the pandemic.

Politics

Coronavirus and the 2020 Election, ACA

Key Findings

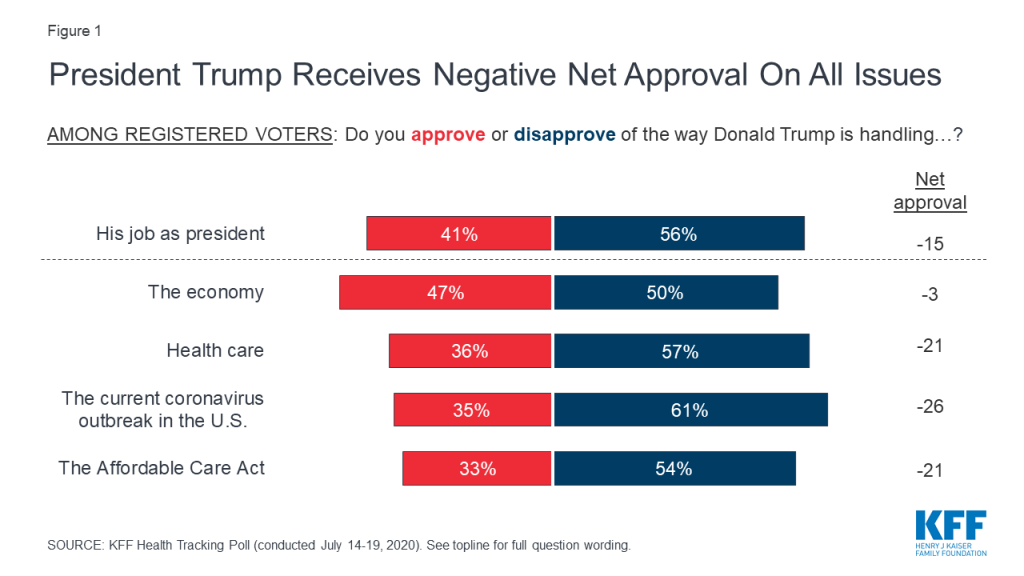

- Less than four months before the 2020 presidential election, the latest KFF Health Tracking Poll finds President Trump receiving his lowest ratings ever from voters on his handling of the coronavirus outbreak. President Trump still garners majority support from Republican voters on all key issues.

- With the number of coronavirus cases in the U.S. now exceeding 4 million people, nearly twice as many voters give President Trump negative marks on his handling of this issue as give him positive marks (61% v. 35%).

- The July poll also explores how two key groups of voters for the 2020 election (swing voters and Electoral College battleground voters) view the job President Trump is doing. About half of these voters approve of President Trump’s handling of the U.S. economy, but similar to overall voters, they disapprove of his handling of other issues.

- President Trump also receives low marks on his handling of health care and the Affordable Care Act, the 2010 health care law which the Trump administration is currently challenging in court. About one-third of voters say they approve of the president’s handling of health care generally (35%) and the Affordable Care Act specifically (33%). Partisans have very different views on President Trump’s handling on both of these issues with most Democrats disapproving while majorities of Republicans approving.

- The public’s views of the Affordable Care Act have largely remained unchanged over the course of the coronavirus pandemic, with half of the public continuing to view the law favorably. There are strong partisan differences in how the public views both the ACA and the pending Supreme Court case challenging the legality of the 2010 law, with Republicans overwhelmingly wanting to see the law overturned while most Democrats want to see the ACA remain in place and largely disapprove of recent Trump administration actions challenging the law.

The 2020 Election

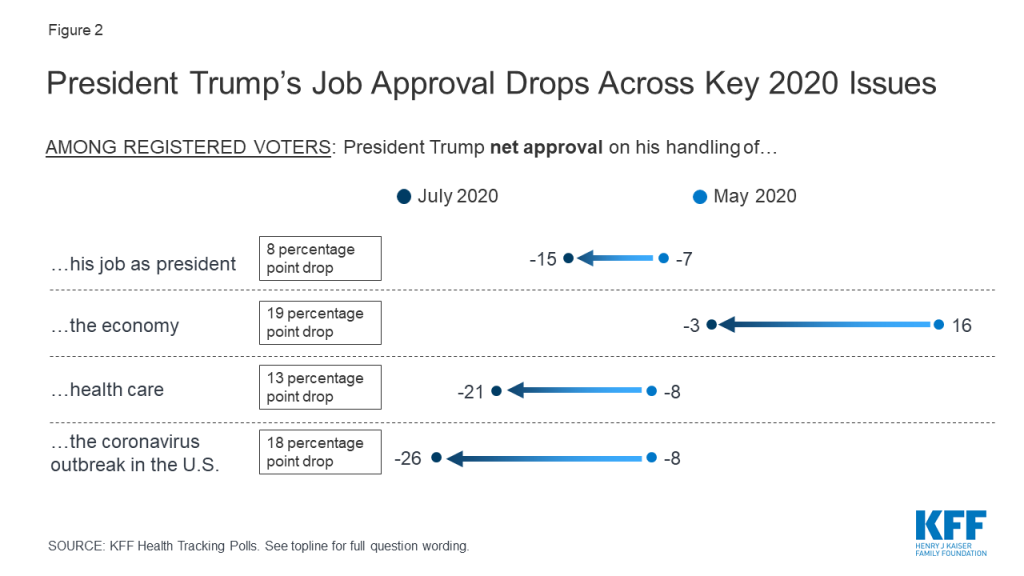

Four months out from 2020 election, voters give President Trump negative ratings on his overall job approval as well as his handling of key issues that will likely decide the election President Trump also now garners his lowest net approval on the handling of the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. since KFF began polling on the topic. One-third (35%) of voters approve of his handling of the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. while six in ten (61%) voters disapprove (net approval of -26 percentage points). President Trump also receives negative ratings on his handling of health care more broadly (net approval of -21 percentage points) as well as his handling of the Affordable Care Act (net approval of -21 percentage points). While President Trump had previously received positive marks on his handling of the economy, voters are now split with 47% approving of his handling of the nation’s economy, and 50% disapproving (resulting in a negative net approval—approval minus disapproval—of -3 percentage points). Overall, four in ten voters (41%) approve of how President Trump is handling his job as president while a majority disapprove (56%).

Voters’ attitudes on President Trump’s handling of both the economy and the coronavirus outbreak have dropped sharply since May 2020. The latest KFF Health Tracking Poll finds President Trump’s overall net approval on these two key issues has dropped nearly 20 percentage points over the course of the summer (economy: 19 percentage point drop in net approval; coronavirus: 18 percentage point drop in net approval).

Voters’ opinions of President Trump’s handling of the issues probed in the poll are largely partisan, with Republicans giving him much higher marks across all of the issues asked about. Majorities of Republican voters approve of President Trump’s handling of his job as president (84%), the economy (87%), health care (78%) and the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. (74%), yet his net approval on each of these issues is down by double digits among Republicans since May.

| Table 1: Across Issues, Trump Net Approval Has Dropped From May to July 2020 Among Partisans | |||||||

| Do you approve or disapprove of the way President Trump is handling… | Democratic voters | Independent voters | Republican voters | ||||

| May 2020 | July 2020 | May 2020 | July 2020 | May 2020 | July 2020 | ||

| …his job as president | Approve | 9% | 5% | 45% | 43% | 90% | 84% |

| Disapprove | 90 | 93 | 54 | 55 | 9 | 15 | |

| Net Approval | -81 | -88 | -9 | -12 | 81 | 69 | |

| Difference in net Approval | 7 percentage point drop | 3 percentage point drop | 12 percentage point drop | ||||

| …the economy | Approve | 23 | 14 | 57 | 47 | 93 | 87 |

| Disapprove | 74 | 84 | 41 | 49 | 6 | 10 | |

| Net Approval | -51 | -70 | 16 | -2 | 87 | 77 | |

| Difference in net Approval | 19 percentage point drop | 18 percentage point drop | 10 percentage point drop | ||||

| …health care | Approve | 9 | 7 | 41 | 33 | 88 | 78 |

| Disapprove | 89 | 89 | 53 | 58 | 9 | 16 | |

| Net Approval | -80 | -82 | -12 | -25 | 79 | 62 | |

| Difference in net Approval | 2 percentage point drop | 13 percentage point drop | 17 percentage point drop | ||||

| …the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. | Approve | 12 | 5 | 44 | 36 | 88 | 74 |

| Disapprove | 88 | 92 | 54 | 61 | 11 | 23 | |

| Net Approval | -76 | -87 | -10 | -25 | 77 | 51 | |

| Difference in net Approval | 11 percentage point drop | 15 percentage point drop | 26 percentage point drop | ||||

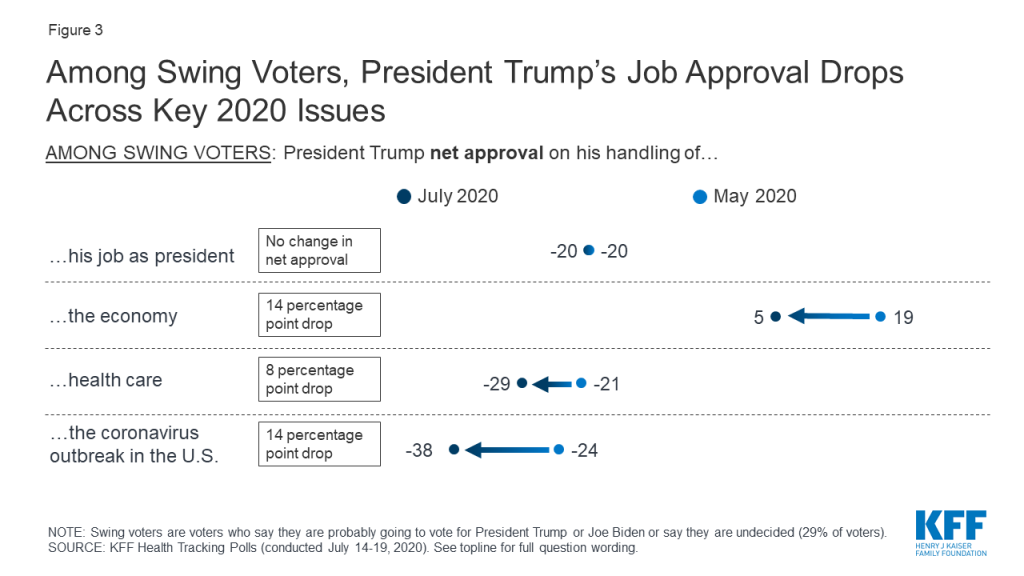

2020 Voters to Watch: Swing Voters

Swing voters, a crucial group of voters who have not yet decided which candidate they will vote for in November, are also negative in their assessments of President Trump’s presidency and his handling of most national issues – but remain positive in their assessment of his handling of the economy. Swing voters (who comprise 29% of all voters) largely disapprove (57%) of the way President Trump is handling his job overall and are also negative in Trump’s handling of both the coronavirus outbreak (66% disapprove) and health care (58% disapprove).

Defining Swing Voters

When asked about their intentions for the upcoming election, voters say they are either “definitely going to vote for President Trump” (30%), or “definitely going to vote for Joe Biden” (36%), while about three in ten voters either say they are undecided in their 2020 vote choice (8%), don’t know yet who they will vote for (2%), or are probably going to vote for President Trump (8%) or Democratic nominee Joe Biden (11%) but have not made up their minds yet.

Swing voters are more positive in views of how President Trump is handling the economy, but at a smaller margin than their assessments in May, with a net approval of +5 percentage points compared to +19 percentage point net approval in May. Swing voters’ assessments of Trump’s handling of health care and the coronavirus outbreak have also become more negative, with the assessments of the president’s handling of health care down 8 net percentage points, and the current coronavirus outbreak down 14 net percentage points.

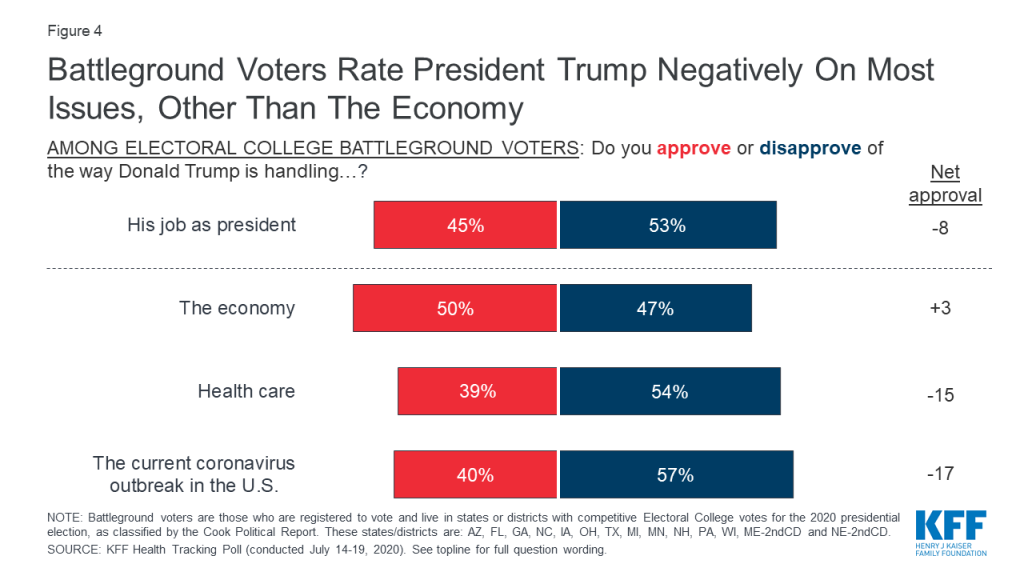

2020 Voters to Watch: Electoral College Battleground Voters

Another important group of voters to watch in 2020 are voters living in states where the election outcome is less predictable. The attitudes of these Electoral College battleground voters will be important in the upcoming election, as their states and districts are likely to swing the Electoral College towards President Trump or Joe Biden.3 This group of voters, representing 38% of all voters, are evenly split in their party preferences, with three in ten saying they are Democrats, Republicans and Independents (31%, 30% and 31% respectively).

President Trump fares slightly better with these battleground voters on all key issues. Half of these voters approve of President Trump’s handling of the economy and 45% say they approve of his handling of his job as president. But similar to the views of all voters and swing voters, President Trump fares slightly worse on his handling of health care and the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S.. Partisan voters in these battleground states and districts fall largely along the same party lines in their evaluations of President Trump, as partisan voters overall.

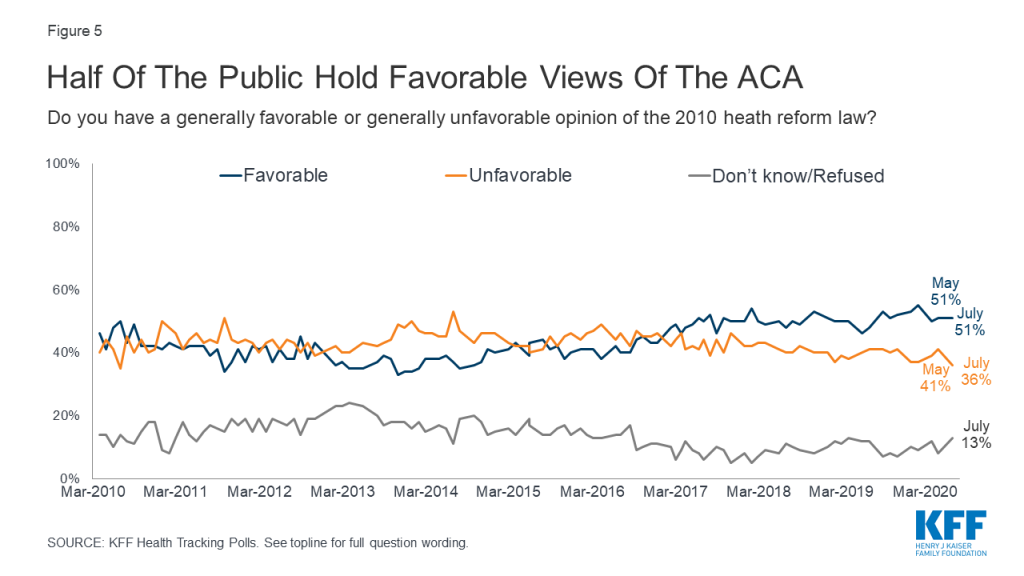

The Affordable Care Act

The public’s attitudes towards the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) have remained relatively unchanged over the past 5 months, with half (51%) now saying they hold a favorable opinion of the law, while 36% hold an unfavorable view.

Partisans continue to hold different views of the ACA, with about eight in ten Democrats (79%) holding favorable views while seven in ten Republicans (72%) view the law unfavorably. Half of independents hold favorable views (51%) while a smaller share (35%) say they view the law unfavorably.

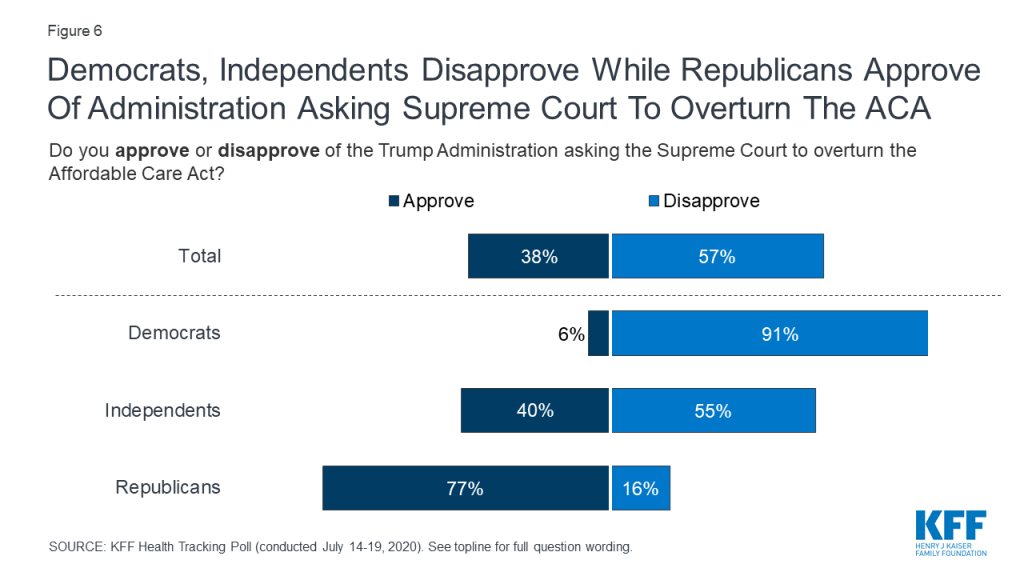

On June 25th, 2020, the Trump administration issued a brief asking the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the entire Affordable Care Act. The brief was filed in support of an ongoing challenge to the ACA by a group of Republican attorneys general in California v. Texas, a case that challenges the legality of the ACA in light of the zeroing out of the individual mandate penalty in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Job Acts. While there is a possibility that the case may be heard in the days leading up to the 2020 election, no opinion is expected to be issued until 2021.

Republicans largely approve (77%) of the Trump administration’s actions, while the vast majority of Democrats (91%) as well as more than half of independents (55%) disapprove of the Trump administration asking the Supreme Court to overturn the ACA.

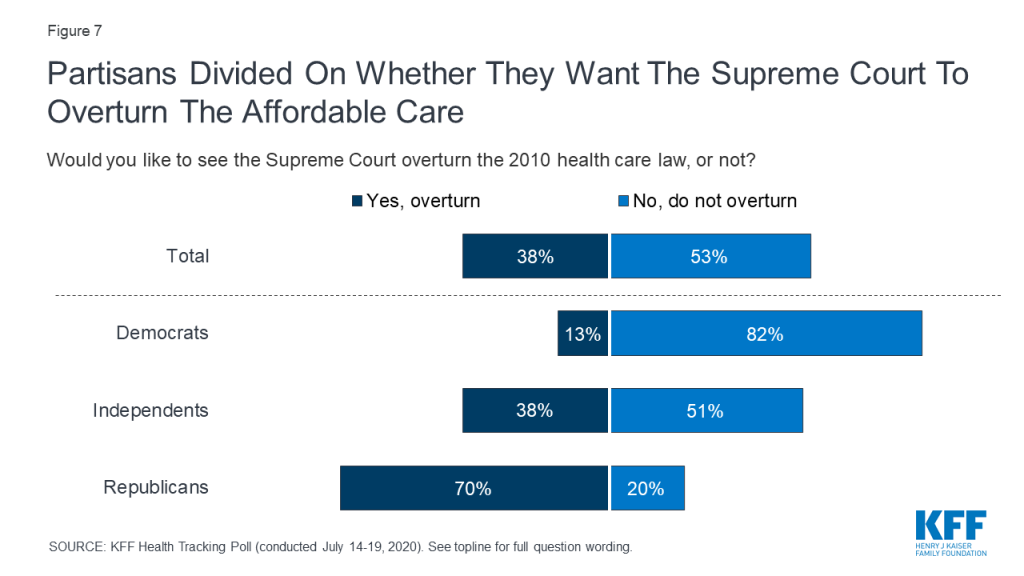

If the Supreme Court sides with the Trump administration and the coalition of Republican attorneys general, all or parts of the 2010 Affordable Care Act would no longer be the law of the land. About half (53%) of the public do not want to see the ACA overturned by the Supreme Court while four in ten (38%) say they want to see the law overturned. Once again, attitudes are largely partisan with eight in ten Democrats (82%) and half of independents (51%) not wanting the law overturned, while seven in ten Republicans say the Supreme Court should overturn the 2010 health care law. Previous KFF polling has found that majorities across partisans want many of the ACA’s protections to remain in place.

Methodology

This KFF Health Tracking Poll was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The survey was conducted July 14-19, 2020, among a nationally representative random digit dial telephone sample of 1,313 adults ages 18 and older, living in the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). The sample included 292 respondents reached by calling back respondents that had previously completed an interview on the KFF Tracking poll at least nine months ago. Computer-assisted telephone interviews conducted by landline (323) and cell phone (990, including 714 who had no landline telephone) were carried out in English and Spanish by SSRS of Glen Mills, PA. To efficiently obtain a sample of lower-income and non-White respondents, the sample also included an oversample of prepaid (pay-as-you-go) telephone numbers (25% of the cell phone sample consisted of prepaid numbers) as well as a subsample of respondents who are parents of children ages 5 to 17 who had previously completed interviews on the SSRS Omnibus and Sports polls (n=101). Both the random digit dial landline and cell phone samples were provided by Marketing Systems Group (MSG). For the landline sample, respondents were selected by asking for the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the opposite gender. For the cell phone sample, interviews were conducted with the adult who answered the phone. KFF paid for all costs associated with the survey.

The combined landline and cell phone sample was weighted to balance the sample demographics to match estimates for the national population using data from the Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) on sex, age, education, race, Hispanic origin, and region along with data from the 2010 Census on population density. The sample was also weighted to match current patterns of telephone use using data from the January-June 2019 National Health Interview Survey. The weight takes into account the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection in the combined sample and also adjusts for the household size for the landline sample, and design modifications, namely, the oversampling of prepaid cell phones and likelihood of non-response for the re-contacted sample. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting. The sample of parents with school-age children was weighted by: gender, age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, and Census region.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total | 1,313 | ± 3 percentage points |

| Party Identification | ||

| Democrats | 398 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Republicans | 330 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Independents | 450 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Parent | ||

| Parent of child(ren) under 18 | 377 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Parent of child(ren) with a child who normally attends school | 308 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Parent/Race | ||

| White Parents | 230 | ± 8 percentage points |

| Parents of color | 136 | ± 11 percentage points |

| Voters | ||

| Registered Voters | 1,117 | ± 4 percentage points |

| Democratic Voters | 353 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Independent Voters | 380 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Republican Voters | 304 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Swing Voters | 285 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Battleground Voters | 419 | ± 6 percentage points |

Cross-tabs

Endnotes

- Due to sample size limitations, we analyzed parents who are Black, Hispanic, Asian, other races, or mixed race as a group (referred to as “parents of color”) compared to their White counterparts. We recognize these groups all have unique experiences; however, the sample size of the poll does not provide sufficient numbers of parents in each of these individual racial/ethnic groups to break out separately. ↩︎

- States were categorized as coronavirus hotspots based on data available from KFF’s COVID-19 Metrics By States on July 20th, 2020 and qualified as a hotspot if cases had increased by 5% of more in the past 14 days and the positivity rate (14-day rolling average) was 10% or greater or if the positivity rate had increased by more than 1 percentage point in the past 14 days. ↩︎

- Using the Cook Political Report’s 2020 Electoral College Ratings, the category of voters living in states and districts classified as “Toss-up”, “Lean Democrat”, and “Lean Republican” are analyzed as Electoral College voters. Voters in this category live in Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska 2nd CD, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Maine 2nd CD, North Carolina, Iowa, Ohio and Texas, constituting 195 volatile electoral votes. ↩︎