What Happens to Medicaid Drug Policy if the ACA is Overturned?

Policy discussions around the potential elimination of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) under the court challenge California v. Texas have largely focused on coverage provisions related to the exchanges, Medicaid and preexisting condition protections. The repeal of the ACA could mean loss of Medicaid coverage for up to 15 million that were enrolled in the ACA Medicaid expansion group prior to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, repeal could also mean significant changes to Medicaid prescription drug policy with implications for state and federal spending for prescription drugs for non-expansion Medicaid enrollees.

Under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), manufacturers who want their drugs covered by Medicaid must enter a federal rebate agreement under which they rebate a specified portion of the Medicaid payment for the drug to the states, who in turn share the rebates with the federal government. The rebate amount is set by statute and includes two main components: a rebate based on a percentage of average manufacturer price (AMP) or the largest “best price” discount provided to most private purchasers, and an inflationary component to account for price increases. The ACA made changes to the amount of rebates and also expanded states’ ability to collect rebates on drugs delivered through managed care plans. In 2010, CBO originally estimated more than $38 billion in federal savings over 10 years for the Medicaid drug-related provisions in the ACA.

How did the ACA affect Medicaid prescription drug policy?

The ACA increased federal drug rebates under the MDRP. The ACA increased base rebate amounts for both generic and brand drugs: the minimum rebate for brand drugs increased from 15.1 percent to 23.1 percent and the base rebate for generic drugs increased from 11 percent to 13 percent. The federal government captures all additional savings. In addition, the ACA established additional rebates for new formulations of existing productions (line extensions), minimum rebates for certain clotting and pediatric drugs, and capped the total rebate amount for drugs at 100% AMP. The law also excluded certain manufacturer discounts from AMP (the price used to calculate rebates) which increase AMP and manufacturer rebate obligations.

The ACA also extended eligibility for rebates to drug benefits provided through managed care. Previously, rebates were only available for drugs purchased through fee-for service (FFS) and many states carved out their drug benefit even if they otherwise provided services through managed care.

The ACA also made other changes to limit Medicaid payment for drugs. These changes include a decrease in federal limits on pharmacy reimbursement for certain multiple source drugs, drugs that have both a brand and generic (FULs).

What are the implications for states and the federal government if the ACA is overturned?

Overturning the ACA could increase federal Medicaid drug spending. Rebates under the MDRP provide a significant offset to Medicaid prescription drug spending, amounting to nearly 60% in 2018. Medicaid base rebates would return to lower, pre-ACA levels and the Medicaid program would receive smaller rebates on generic drugs and certain brand drugs for traditional Medicaid populations. This would largely impact federal spending, as the rebate increase from the ACA accrues to the federal government. Medicaid would also no longer receive additional rebates for line extension drugs and the federal reimbursement benchmark (FUL) would increase to pre-ACA amounts for certain multisource drugs. In addition, the AMP for some drugs could decrease without the exclusion of certain manufacturer discounts, lowering rebates and increasing spending for both states and the federal government.

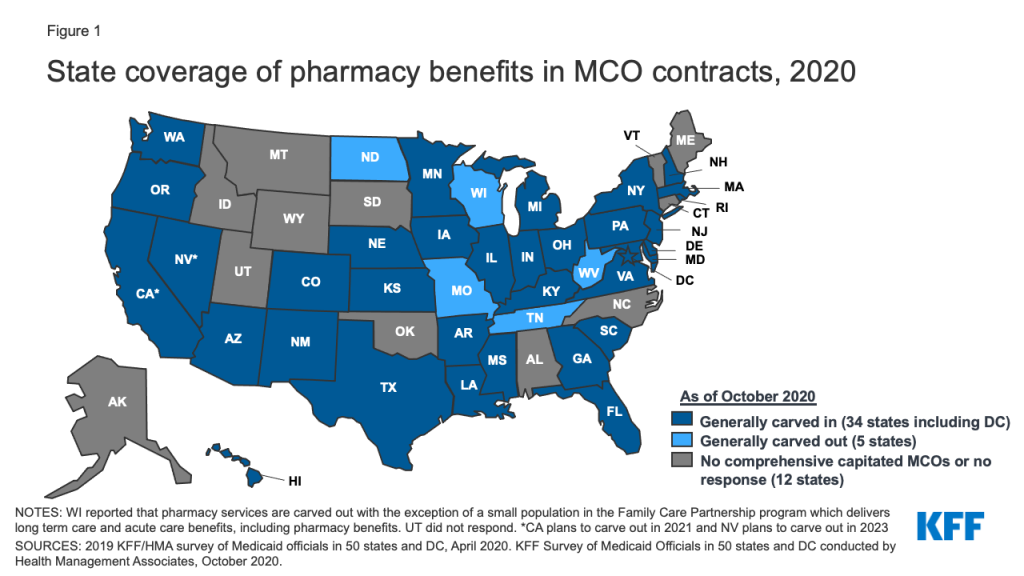

States would no longer be able to collect rebates for drugs provided through managed care. This would be a significant loss in rebates for states and the federal government, and to avoid these losses, states would need to carve out the pharmacy benefit from managed care. Over the 2010–2015 period, CBO estimated the share of Medicaid outpatient drug spending covered through Medicaid managed care plans grew from about 10 percent to roughly half. As of October 2020, 34 of 40 MCO states carved in the pharmacy benefit (Figure 1). States could negotiate additional supplemental rebates with manufacturers but they would be unlikely to offset other rebate losses.

The elimination of the ACA would have fundamental implications for access to care for up to 15 million individuals in the expansion group, but would also increase federal drug spending for non-expansion Medicaid enrollees. Federal Medicaid drug spending could increase as the federal government would receive lower rebates on drug spending for traditional Medicaid populations. States would also need to restructure how the drug benefit is delivered to avoid rebate losses as most now provide the benefit through managed care.