How Corporate Executives View Rising Health Care Cost and the Role of Government

Introduction

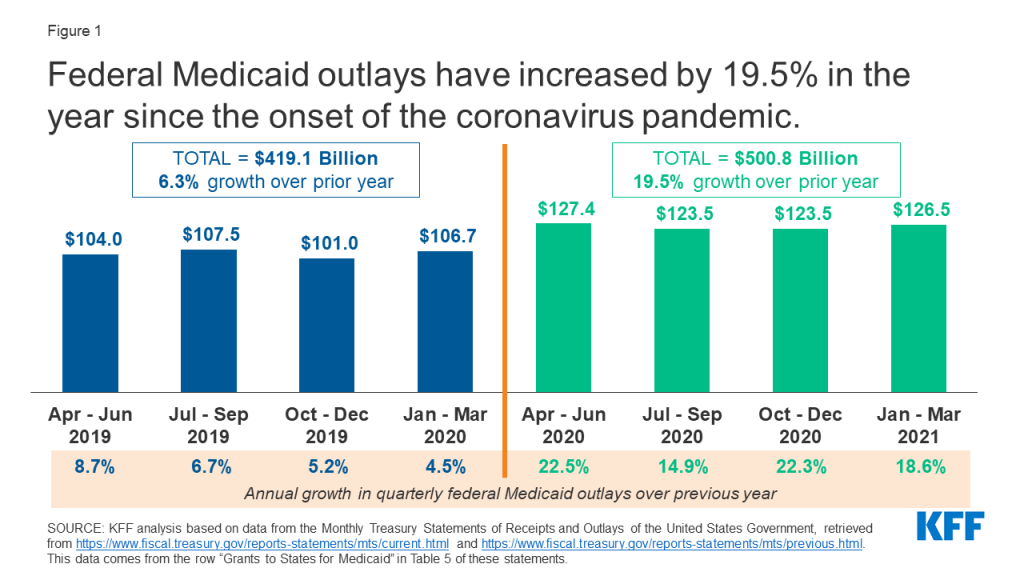

With the events of past year, how we view health care in the United States is changing. The COVID pandemic has made even more clear the problems with our current system, including high costs, incomplete coverage, limited access to care, under-investment in public health, and serious racial and ethnic inequities. All of this, occurring against a backdrop of ever-rising health care costs, is causing many to re-think their priorities and positions on key health care policy issues.

In addition, the recent election has changed the political landscape and extended the range of policy options that likely will be discussed at the national level. During his campaign, President Biden proposed new coverage options that would broaden access to public coverage. One would create a Medicare-like public health coverage option that some people could elect in lieu of their current coverage. Another would lower the age of eligibility for Medicare to age 60. In addition, there appears to be bipartisan support for strengthening antitrust enforcement and limiting anti-competitive actions that are used by some health care entities to gain market power and increase prices, including proposals that would regulate or cap prices for high-cost drugs. Each of these proposals interject an expanded public role in providing coverage and restraining costs for populations that are largely now served by private health plans. Since these proposals are controversial and likely to face opposition from large parts of the health care industry, it is important to assess the level of support among key stakeholders.

Large employers are a primary source of private coverage, and thus are important stakeholders who will be influential in policy debates. Their views on health policy issues, however, are largely unknown. Many assume that business leaders tend to favor market solutions and oppose government involvement, but this is untested. Our objective was to find out what business leaders felt about health care issues – especially cost and coverage – and their opinions about potential government actions to address these problems.

To better understand how large employers may react to these and similar proposals, the Purchaser (formerly “Pacific”) Business Group on Health (PBGH) and the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) surveyed executive decision-makers at over 300 large private employers about how they view the costs of health care and health coverage and the potential advantages and disadvantages of increasing the government’s role in providing health coverage and reducing costs. The interviews were conducted in December 2020 and January 2021 by Beresford Research. The research project was supported by a grant from the Gary and Mary West Health Institute.

At a high level, we found significant concerns regarding health care costs. A significant majority of responding large employers “moderately” (49%), considerably (28%), or “strongly” (6%) agreed that the cost of health benefits is excessive. Employers did not blame any single cause for excessive costs, with large shares agreeing that the cost of prescription drugs, provider market consolidation and increased market power, volume-based payments, and unhealthy behaviors each are “moderate” or “considerable” or “very large” factors for high costs.

In addition, we found a significant amount of agreement with the need for greater government roles in providing coverage and addressing health care costs. A majority of responding large employers expressed some level of agreement with policy changes that would create a public option for employees and lower the Medicare eligibility age, both for their own employees and for the public more generally. Equally interesting, only small shares expressed disagreement with these ideas.

Majorities of responding large employers also expressed agreement with the need for more government involvement in containing health care costs. Interventions including capping hospital prices in non-competitive markets, limiting out-of-network charges, and negotiating or limiting drug prices in certain cases all had majority support. There was considerable support for pursuing policies that would increase transparency of prices and costs and that would increase antitrust enforcement or otherwise address non-competitive conduct. Overall, large shares of respondents agreed that a greater role for the government in providing coverage and containing health care costs would better for their business (83%) and better for their employees (86%).

Findings

APPROACH

PBGH and KFF worked with Beresford Research to survey key decision-makers at large U.S. employers that provide health benefits to their employees. Respondents were surveyed about their views around the cost of health benefits and potential expansion of government roles in providing benefit alternatives and in addressing health care costs. The survey was designed by researchers at KFF, PBGH, and Beresford Research. Telephone surveys were completed by Beresford Research with a convenience sample of representatives from 302 employers with at least 5,000 employees, widely distributed by region and industry. Respondents were chief executive officers, chief financial officers, chief operational officers, chief human resource officers, or people directly reporting to those positions. A detailed breakout of respondents is shown (see Toplines). Follow-up conversations were completed with 10 of the respondents to get additional information and perspective on their views. The telephone surveys were completed in December 2020 and January 2021. KFF and PBGH researchers analyzed the responses and prepared this report.

BACKGROUND

Health benefits make up a meaningful share of employee compensation, averaging 7.3 percent for private-sector employers. While annual growth in benefit costs has been modest in recent years (at least relative to prior decades), benefit costs are already high and they continue to increase faster than wages and prices in general. Employer health plans already pay much higher prices for health care goods and services than public coverage programs, and the gap is growing. Provider consolidation, particularly among hospitals, limits the potential for competitive strategies to reduce benefit costs. Pricing for new pharmaceutical products, where manufacturers have significant power to set prices, also fuels cost growth. Innovative approaches developed by employers and other payers to address costs (e.g., centers of excellence for back surgeries; expanding virtual care alternatives; value-based cost-sharing) may affect the rate of cost growth, but they have had little impact on reducing cost levels or reducing the gap with respect to public payment rates.

The recent election brought into office policymakers, including the new President, who support more expansive governmental roles in both coverage and cost containment. As a candidate, President Biden proposed providing people with the choice to enroll in a new public health insurance option, similar to Medicare, that would negotiate prices with health care providers. The option would be broadly available, including to employees and family members now covered through employer-based coverage. People offered employer-based plans generally are not eligible for this assistance now, though President Biden’s campaign plan would remove that restriction. Candidate Biden also proposed, as part of the Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force proposals, that people be given the option of enrolling in Medicare when they turned age 60.

In terms of health care costs, President Biden made several proposals to restrain prices and cost growth that could assist sponsors and enrollees in employer-based plans including government negotiating of drug prices, limiting price growth for new brand, biotech, and certain generic drugs, aggressively using anti-trust authority to address consolidation in health care markets, restricting surprise medical bills, and accelerating the development and use of generic drugs and biosimilars.

FINDINGS

The responding employers largely believe that the cost of health benefits is excessive. While in general respondents felt that employers individually or collectively can have an impact on health care costs, more than four in five believe that the cost of providing health benefits will become unsustainable at some point in the next five to ten years, and that there will need to be a greater role for government in providing coverage and controlling costs. Respondents generally expressed some agreement with a variety of policies that would expand the government’s role in health benefits, including limiting provider prices in non-competitive situations and expanding options for employees and others to enroll in public programs.

Cost of Health Benefits

Nearly all respondents agreed that health benefit costs are excessive. About half (49%) of respondents moderately agreed with the statement that employer costs for health benefits are excessive, with another 33% considerably or strongly agreeing. Only 4% of respondents disagreed with the statement.

Respondents did not single out any one factor as the primary reason for excessive costs. We asked respondents about the importance of four contributors to high health care costs: prescription drug prices; market consolidation among hospital and health care provider consolidation (with increased market power to raise prices); unhealthful behaviors among large segments of the population; and payments to hospitals and clinicians based on volume of services and not on patient outcomes. The pattern of responses was similar for each, with large shares of respondents saying that each was a “moderate” or “considerable” reason for high costs.

Although respondents largely agreed that the cost of health benefits is excessive, large shares believe that employers can change the cost of health care to some extent, both overall and for their own companies. Over half (56%) of respondents agreed that employers collectively can change health care costs to a moderate extent, with another 29% agreeing that employers can change costs to a considerable or large extent. For their own companies, 42% said that they could change health care costs to a moderate extent while 35% said that they could change costs to a considerable or large extent.

When asked why they believed that employers could influence costs, respondents mentioned things such as the ability to adjust employee costs (deductibles and worker contributions) or benefits as well as the potential of wellness programs to moderate costs. Others noted that many factors were outside of employer control. Large shares of respondents said that they were at least moderately likely to implement one or more cost-control practices, ranging from value-based benefit designs to higher deductibles.

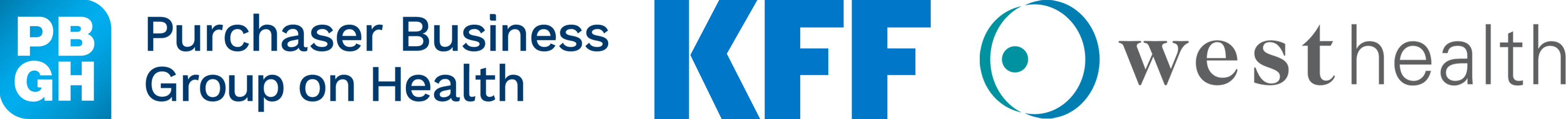

Even while a majority of respondents felt that they could change the costs of health care, 87% of respondents believe that the cost of providing health benefits to employees will become unsustainable in the next 5 to 10 years, and 85% believe that there will need to be greater government roles in providing coverage and containing costs.

Greater Government Roles in Cost and Coverage

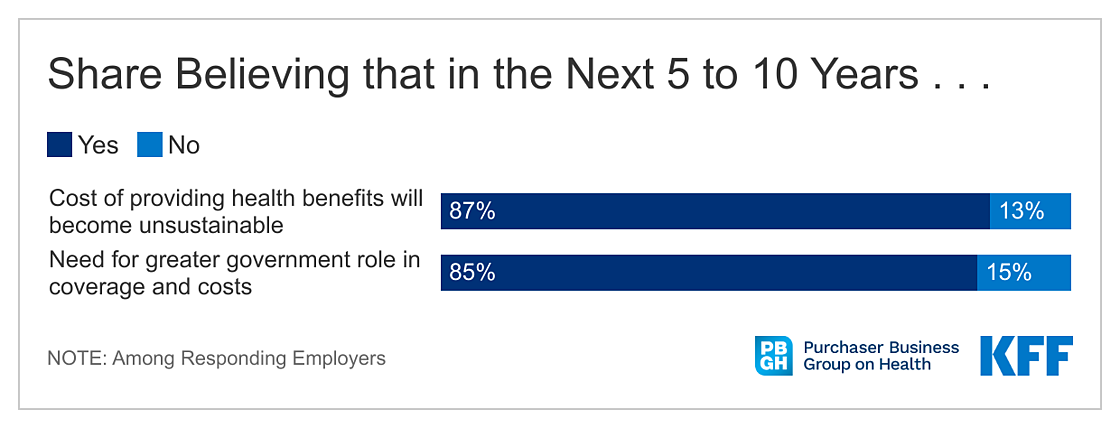

Respondents overwhelmingly believe that a greater government role in providing coverage and containing costs would be better for their business (83%) and better for their employees (86%). Respondents who said that a greater government role might be better for their business or their employees were asked why they thought so; among those who believed it would be better for their business, 43% said that it could reduce employee premium costs and 42% said that it could reduce costs for employers. Other potential benefits mentioned by these respondents included improving employee health and productivity and providing more benefit options for employees.

We asked respondents about their support for more specific government policies that would increase the government’s role in controlling health care costs, particularly in non-competitive market situations. Large shares of respondents agreed that policymakers should pursue policies that would strengthen anti-trust enforcement and prohibit anti-competitive conduct by providers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and health plans (92%) or improve the transparency of prices and the total cost of care (90%). Although less well supported, 56% of respondents thought policymakers should pursue policies to reduce barriers to the development and use of generic drugs and biosimilar products.

Many respondents also expressed some support for more direct government intervention in health care pricing in certain circumstances. More than one-third of respondents “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed with government policies that would cap prices for hospitals in markets with limited or no competition; limit prices charged by out-of-network providers in surprise billing situations, and negotiate prices for high-cost sole-source drugs or setting limits on drug price increases. Fewer than 5% of respondents expressed any disagreement with any of these potential interventions.

In addition to policies to directly control health care prices and spending, we asked respondents about two proposals made by President Biden during his campaign that would extend public benefit coverage options to more people, including people with employment-based coverage. The first would create a public program option, similar to Medicare, broadly available to residents, and the second would provide people the option of enrolling in Medicare when they reach age 60.

These proposals could be of interest to employers because they are potential alternatives to the employment-based benefits that they offer, and which could be available to employees at the employee’s option. Depending on the financing, these options could reduce employer costs by reducing plan enrollment; this could be particularly significant in the case of lowering the Medicare eligibility age because older workers have some of the highest costs on average in employer plans. At the same time, providing options to employees could be disruptive to employer plans and upset planning, at least at the outset, and particularly if employees could move back and forth. Employers also may be concerned that they may be asked to participate in the financing of these options, which could offset any potential cost savings.

Respondents were asked about their level agreement with these two proposals, for either the general public or for their employees. Overall, large shares of responding employers expressed at least slight agreement with each proposal, both for the public in general and for their own employees. Perhaps surprising, few respondents expressed any level of disagreement with the options, with virtually no strong disagreement expressed by any respondent. This lack of disagreement may reflect the lack of detail about how these coverage options might operate or be financed, but it appears that employers may be open to this type of proposal and not opposed in general to extending public coverage options to more people, including their own employees.

More generally, we also asked respondents for their opinions about several potential advantages and disadvantages that could result from greater government roles in health care coverage and costs. As potential positives, about three in five respondents agreed that a greater government role might relieve employers of the responsibility and costs of managing health benefits, with a similar percentage agreeing that it may enable the government to hold down health care costs. Forty-seven percent of respondents said that a greater government role may enable increased consumer choices, while only 29% said that it could reduce administrative costs. As potential negatives, 43% said that the government does not have a great track record of managing big programs effectively, 41% said that the political influence of the health care industry would deter government actions to reduce costs, and 30% said that the government may not be able to design benefits to meet employee needs.

DISCUSSION

The business executives we surveyed showed perhaps a surprising degree of openness to proposals that would increase government roles in health care. Judging from some of the follow-up interviews, this openness appears to be less reflective of a belief that the government operates programs better or more effectively than the private sector, and more reflective of a long-standing frustration with the health care system and what are perceived to be constant and excessive increases in costs with little transparency into why they occur. More than four in five respondents agreed that the cost of providing health benefits would become unsustainable in the not too distant future and that this would necessitate a greater government role in providing coverage and restraining costs. As one respondent noted in a follow-up interview, “if it’s not the government stepping in, who would it be?”

While many respondents are confident that they can affect their own benefit costs at least to some degree, the primary levers they mentioned – increasing employee costs or reducing benefits – are not necessarily appealing or consistent with the goal of having an attractive benefit package for current and prospective employees. From this perspective, proposals to cap or limit prices in cases where markets are not working may be attractive to business executives because they offer employees some respite from high prices without reducing benefits or increasing enrollee costs. One respondent noted in the follow-up interviews about why he felt that government intervention was needed:

Over the long-term, yes. I think it will be business’ approach to continue to cut costs and cut benefits to control costs, simply because we don’t have the scale with which to really affect the change in the cost to us as well as we would want to. The end result is our employees get less benefits and use more of their take-home pay towards their share of their benefits to subsidize what the employer needs. I do think the model has to change because we’re going to be delivering less value to our employees unless the model does change and more pressure is put back in control of pricing to the providers and to the healthcare system generally.

The proposals to expand government programs also may be seen as an opportunity for employers to offload some of their costs, which may explain the clear openness to the ideas without any strong disagreement. In particular, providing people age 60 with the option to enroll in Medicare could help employers with some of their most costly enrollees. While the financing and benefit details associated with these proposals will be very important in how employers ultimately assess them, what seems clear from the responses is that respondents were more worried about the status quo than the prospect of a greater government role in providing health coverage alternatives for their workers.

The new political landscape may portend a new and more viable discussion of expanded roles for government in providing health coverage and restraining prices and costs. While this has long been controversial, the results of this study suggest that the employers are frustrated by the current health care system and their limited opportunities to address cost and that they may be open to options that involve a broader role for government.

This work was supported in part by the West Health Institute. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.