Editorial Note: This brief was updated on July 18, 2023, with newer data. It was originally published on July 8, 2022.

In 2020 and 2021, firearms contributed to the deaths of more children ages 1-17 years in the U.S. than any other type of injury or illness. The child firearm mortality rate has doubled in the U.S. from a recent low of 1.8 deaths per 100,000 in 2013 to 3.7 in 2021.

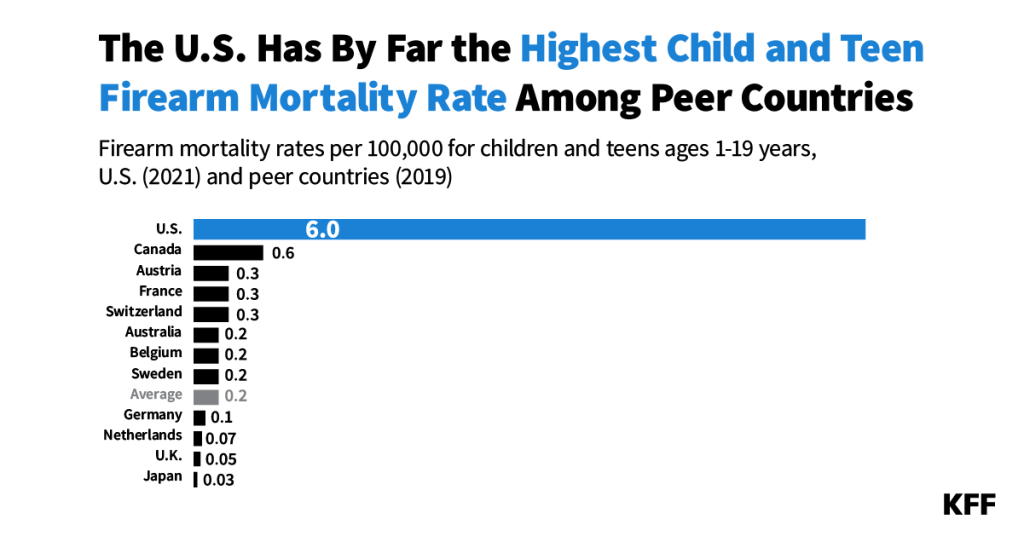

The United States has by far the highest rate of child and teen firearm mortality among peer nations. In no other similarly large, wealthy country are firearms in the top four causes of death for children and teens, let alone the number one cause. U.S. states with the most gun laws have lower rates of child and teen firearm deaths than states with few gun laws. But, even states with the lowest child and teen firearm deaths have rates much higher than what peer countries experience.

In 2020 and 2021, firearms were involved in the deaths of more children ages 1-17 than any other type of injury or illness, surpassing deaths due to motor vehicles, which had long been the number one factor in child deaths. In 2021, there were 2,571 child deaths due to firearms—a rate of 3.7 deaths per 100,000 children, which is an increase of 68% in the number of deaths since 2000 and 107% since a recent low of 2013.

While the rate of firearm deaths among children has increased since 2000, the rate of motor vehicle deaths is now significantly lower than it had been. The number of motor vehicle deaths among children in 2021 was 49% lower than in 2000, though it did grow during the pandemic by 22% from 2019. Though fewer in number than firearm deaths among children, deaths due to poisonings, which include drug overdoses, have also grown, increasing 186% since 2000 and 103% since 2019.

Provisional CDC data from 2022 indicate that firearms continued to be the number one factor in child deaths for the third year in a row.

Because peer countries’ mortality data are not available for children ages 1-17 years old alone, we group firearm mortality data for teens ages 18 and 19 years old with data for children ages 1-17 years old in all countries for a direct comparison.

On a per capita basis, the firearm death rate among children and teens (ages 1-19) in the U.S. is over 9.5 times the firearm death rate of Canadian children and teens (ages 1-19). Canada is the country with the second-highest child and teen firearm death rate among similarly large and wealthy nations.

As might be expected, teenagers have higher firearm mortality rates than children. In the U.S., teens ages 18 and 19 have a firearm mortality rate of 25.2 per 100,000, compared to a rate of 3.7 per 100,000 for children ages 1-17 in the U.S. Even so, the child firearm mortality rate in the U.S. (3.7 per 100,000 people ages 1-17) is 5.5 times the child and teen mortality rate in Canada (0.6 per 100,000 people ages 1-19).

If the child and teen firearm mortality rate in the U.S. had been brought down to rates seen in Canada, we estimate that approximately 30,000 children’s and teenagers’ lives in the U.S. would have been saved since 2010 (an average of about 2,500 lives per year). This would have reduced the total number of child and teenage deaths from all causes in the U.S. by 13%.

The child and teen (ages 1-19 years) firearm mortality rate varies by state in the U.S. from 2.1 deaths per 100,000 in New York and New Jersey to 17.6 deaths per 100,000 in Louisiana. Even in New York and New Jersey, which have the lowest child and teen firearm mortality rates among those with available data, the rate is still over three times that in Canada.

Because there is no comprehensive national firearm registry, it is difficult to track gun ownership in the U.S. Instead, we look at the correlation between the number of child and teen firearm deaths and the number of gun laws in U.S. states (based on the State Firearm Law Database, which is a catalog of the presence or absence of 134 firearm law provisions across all 50 states).

States with more restrictive firearm laws in the U.S. generally have fewer child and teen firearm deaths than states with fewer firearm law provisions. Even so, these states on average have a much higher rate of child and teen firearm deaths than that of Canada and other countries. Among comparably large and wealthy countries, Canada has the second highest child and teen firearm death rate to the U.S. However, Canada generally has more restrictive firearm laws and regulates access to guns at the federal level. In the U.S., guns may be brought to states with strict laws from out-of-state or unregistered sources.

In 2020 and 2021, firearms were involved in more deaths for children and teens (ages 1-19 years) in the United States than any other type of injury or illness. In 2021, firearms were involved in 4,733 child and teen deaths.

With the exception of Canada, in no other peer country were firearms among the top five causes of childhood and teenage death. Motor vehicle accidents and cancer are the two most common causes of death for this age group in all other comparable countries.

The categories in the chart above are more specific than CDC’s rankable causes of death. We use CDC’s data grouped by injury mechanism and illness. However, given differences in how deaths are grouped by CDC and IHME, we adapt CDC data to be comparable to IHME data. For example, pedestrian deaths are included with motor vehicle and pedestrian deaths in the chart above. See Methods for more details.

Combining all child and teen firearm deaths in the U.S. with those in other OECD countries with above median GDP and GDP per capita, the U.S. accounts for 97% of gun-related child and teen deaths, despite representing 46% of the total population in these countries. Combined, the eleven other similarly large and wealthy countries account for only 153 of the total 4,886 firearm deaths for children and teens ages 1-19 years in these nations, and the U.S. accounts for the remainder.

Firearms account for 20% of all child and teen deaths in the U.S., compared to an average of less than 2% of child and teen deaths in similarly large and wealthy nations.

The U.S. also has the highest rate of each type of child and teen firearm death—suicides, assaults, and unintentional or undetermined intent—among similarly large and wealthy countries.

In 2021 in the U.S., the overall child and teen firearm assault rate was 3.9 per 100,000 children and teens. In the U.S., the overall suicide rate among children and teens was 3.8 per 100,000; and 1.8 per 100,000 child and teen suicide deaths were by firearms. In comparable countries, on average, the overall suicide rate is 2.8 per 100,000 children and teens, and 0.2 per 100,000 children and teens suicide deaths were by firearms.

If the U.S. child and teen suicide by firearm rate was brought down to the same level as in Canada, the peer country with the next highest rate, over 1,000 fewer children and teens would have died in 2021 alone.

The spike in 2020 and 2021 in child and teen firearm deaths in the U.S. was primarily driven by an increase in violent assault deaths. The child and teen firearm assault mortality rate reached a high in 2021 with a rate of 3.9 per 100,000, a 7% increase from the year before and a 50% increase from 2019. The firearm suicide mortality rate among children and teenagers in the U.S. increased 21% from 2019 to 2021.

Exposure and use of firearms also have implications for mental health. Research suggests that youth may experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety in response to gun violence. Specifically, survivors of firearm-related injuries, including youth survivors, may be at increased risk of mental health conditions and substance use disorders. Furthermore, gun violence disproportionately affects many children of color, particularly Black children, and children living in areas with a high concentration of poverty.

Methods

Data from CDC Wonder 2021 Underlying Cause of Death database and IHME Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 study (Level 2 Causes of Death) were used. CDC Wonder Underlying Cause of Death grouped by Injury Mechanism and All Other Leading Causes data are used for the U.S., and IHME GBD data are used for other countries. While CDC Wonder data are available by single-year age, IHME data are only available by broad age groups (e.g., ages 1-4 years and 5-19 years). Given that international estimates are not available for children ages 1-17, we use ages 1-19 for comparisons to other countries.

Mortality rates for comparable countries were calculated using population estimates from United Nations (UN) Population Prospects data. Mortality rates for the U.S. were taken from CDC Wonder. For the calculations of potential lives saved in the U.S., we use the upper limits of IHME’s estimates of number of deaths to minimize risk of overestimation. For estimating child and teen firearm mortality over time in the U.S., Underlying Cause of Death by Bridged-Race Categories were used between 2000 and 2018, and Underlying Cause of Death by Single-Rate Categories for 2018 through 2021.

Differences in the categorization of causes of death between the CDC and IHME were addressed by adapting the Level 2 Causes of Death categories from IHME’s GBD study. The top 20 causes of death, aggregated regardless of intent, were ranked. These top 20 causes of death include: firearms, motor vehicle traffic, other injuries, congenital diseases, cancer, substance use disorders, cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, respiratory infections, neurological disorders, diabetes and kidney diseases, maternal and neonatal complications, digestive diseases, nutritional deficiencies, HIV/AIDS and STIs, musculoskeletal disorders, skin and subcutaneous diseases, other mental disorders, and neglected tropical diseases. Unintentional firearm deaths include undetermined intent firearm deaths. Motor vehicle deaths include motor vehicle, pedestrian, other transport, being struck by or against a vehicle in traffic, and other land transport deaths. Other injuries encompass all injuries that are not from firearms, motor vehicles, or poisonings from substance use disorders, but not from injuries incurred via medical care. Cancer includes both malignant and in situ neoplasms. Congenital diseases include congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal disorders, as well as any disease/disorder that could not be identified via laboratory tests or examinations. Other mental disorders (not shown in the tables above but accounted for in analyses) include all deaths from mental health disorders, excluding suicide via firearm or other injury or poisonings via substance use disorder.