National health spending totaled $4.5 trillion in 2022—17% of gross domestic product (GDP)—and is projected to grow faster than GDP through 2031, contributing to higher costs for families, employers, states, and the federal government. As policymakers consider a variety of strategies to make health care more affordable, they have been increasingly attentive to consolidation in health care markets—including mergers and acquisitions of health care providers—and the potential effects of consolidation on the cost and quality of care and other outcomes. Consolidation may allow providers to operate more efficiently, and could help struggling providers keep their doors open in underserved areas, but also often reduces competition. A substantial body of evidence has found that consolidation has led to higher prices, but the evidence on quality is unclear.

In response to concerns about the effects of consolidation and reduced competition on prices and quality, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recently authorized a lawsuit to block a hospital acquisition in North Carolina. And, just last month, the FTC, Department of Justice, and Department of Health and Human Services issued a request for information (RFI) seeking input on the effects of consolidation involving health care providers and related products and services as part of a broader effort to clamp down on anticompetitive practices.

This issue brief identifies ten things to know about consolidation in health care provider markets, touching on topics such as the different types of consolidation, trends, ways in which consolidation can be beneficial or harmful for patients and other consumers, some key findings from existing research, and policy options for increasing competition. This brief focuses on consolidation among health care providers, rather than health insurers, and builds on a 2020 KFF issue brief on provider consolidation. More recent research has not altered the key takeaways pulled from that brief.

Efforts to promote more competitive provider markets could help address health spending and affordability issues, but also entail a number of challenges, given that many markets are already highly concentrated and that some regions cannot support competitive markets. Some have considered more direct regulation of prices and spending, and the two approaches could play complementary roles when addressing rising health care costs, such as by encouraging providers to compete on quality when prices are regulated.

Health care consolidation often refers to scenarios where hospitals and other health care entities join together under common ownership through either a merger or acquisition (referred to as “mergers” in this brief). There are three main types of mergers:

- Horizontal mergers occur when there is consolidation between entities that offer the same or similar services, such as when a health system acquires a hospital or when two physician practices that provide overlapping services merge. For instance, in August 2023, Oregon Health & Science University and Legacy Health—two of the largest health systems in the Portland area—announced plans to merge.

- Vertical mergers occur when there is consolidation between entities that offer different services along the same supply chain, such as when a hospital or health plan acquires a physician practice. For instance, in May 2023, the health system HCA Healthcare announced a deal to acquire 41 urgent care centers in Texas, where HCA already had a large presence. Some mergers may entail both vertical and horizontal consolidation (e.g., if a health system acquires a physician practice that provides services offered by the system’s existing physician group).

- Cross-market mergers occur when there is consolidation between two providers that operate in different geographic markets for patient care. For example, in March 2024, Kaiser Permanente closed its merger with Geisinger Health through a new organization called Risant. These systems operate in different regions of the United States, with Kaiser Permanente operating in five states in the West (including California) and Georgia, Maryland, Virginia, and DC and Geisinger operating in Pennsylvania.

Aside from merging, health care entities can form other types of affiliations without necessarily changing ownership, which may also have implications for patient care. Examples include the creation of accountable care organizations (i.e., groups of doctors, hospitals, and other providers who form partnerships to collaborate and share accountability for the cost and quality of care delivered to their patients) and joint ventures (i.e., agreements to collaborate on a particular goal, such as a health system and group practice that work together to create a new ambulatory surgery center). These affiliations can raise similar issues as mergers and are sometimes referred to as “soft” forms of consolidation.

2. There has been a large amount of consolidation in provider markets over the past 30 years

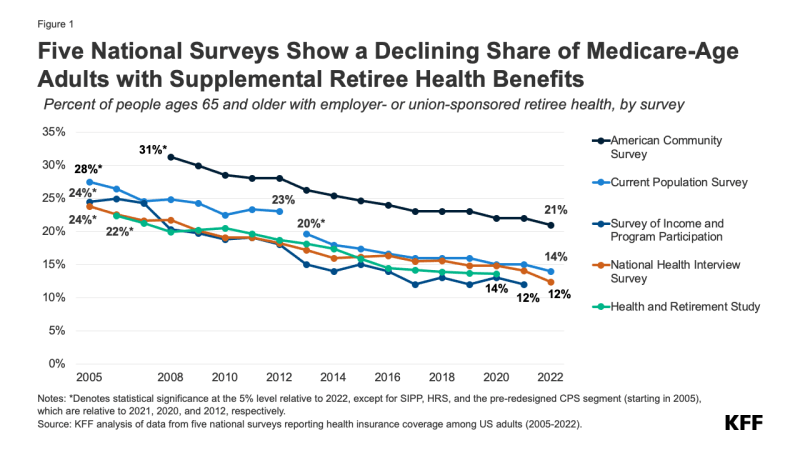

Provider markets have become increasingly consolidated over the past 30 years. Following a wave of consolidation in the early- and mid-1990s, there were 1,573 hospital mergers from 1998 to 2017 and another 428 hospital and health system mergers announced from 2018 to 2023. The share of community hospitals that are part of a larger health system also increased from 53% in 2005 to 68% in 2022 (see Figure 1). Relatedly, the share of physicians working for a hospital or in a practice owned at least partially by a hospital or health system increased from 29% in 2012 to 41% in 2022.

Consolidation has also contributed to the emergence of large health systems. For example, the ten largest health systems (see Table 1) accounted for about one in five (22%) of nonfederal general acute care hospital beds in 2022. These systems are the size of large corporations. For example, HCA Healthcare, which operates the largest number of nonfederal general acute care hospital beds in the country, had greater operating revenues than each of Netflix, Uber, and Starbucks in 2023. AdventHealth, the smallest of the ten largest health systems in terms of beds, had greater operating revenues than Zoom and Lyft combined in 2023 (as did Community Health Systems, the smallest of the ten largest systems in terms of operating revenues). Consolidation, which often occurs between providers based in the same region, has also contributed to highly concentrated markets where patients have limited options among large provider organizations.

Today, many provider markets are highly concentrated, particularly markets for hospital care. One study estimated that the vast majority (90%) of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) had highly concentrated hospital markets in 2016, while another estimated that the share of metro areas with highly concentrated hospital markets increased from 71% to 77% over the period from 2017 to 2021 (differences in magnitudes across these studies likely reflect their distinct methods, including market definitions). The former also found that most MSAs (65%) had highly concentrated specialist physician markets in 2016, and nearly two in five (39%) had highly concentrated markets for primary care physicians. Physician markets may have become more concentrated in recent years due to the ongoing trends in consolidation described above.

3. Corporations such as CVS, Amazon, and UnitedHealth and private equity firms have recently acquired many physician practices

In addition to hospitals and health systems, other types of entities have also been involved in a large number of acquisitions in recent years:

- Corporate buyers. Corporations that have not traditionally specialized in the provision of health care services—including large national companies such as CVS, Amazon, and UnitedHealth—have acquired many physician practices in recent years. The share of physicians employed by corporate entities increased over a three-year period from 15% in January 2019 to 22% in January 2022. Optum, a division of the insurer UnitedHealth, now employs or is affiliated with about 10% of all practicing physicians. Some policymakers have expressed concern about the role that large corporate buyers could have in increasing consolidation and reducing competition, which could lead to higher costs and reduced quality, although evidence is not yet available on this trend.

- Private equity firms. Private equity is a form of corporate ownership that often entails relying on loans to acquire a business, taking it private (if not so already), and attempting to increase its value with the goal of selling it at a profit in three to seven years. One common strategy is to consolidate providers through a series of mergers and acquisitions. Private equity provider acquisitions have increased by a large amount since 2010—e.g., with physician practice deals increasing more than six-fold from 2012 to 2021—though deals have slowed somewhat since a peak in 2021. Some policymakers have expressed concern about the role of private equity in consolidation and the effect of the short-term profit motive of private equity firms on the prices, quality, and financial standing of acquired providers.

4. A substantial body of evidence shows that consolidation has led to higher prices, but the evidence on quality is unclear

Consolidation could in principle benefit consumers in some instances and be harmful in others. On the one hand, consolidation could allow providers to operate more efficiently, such as by obtaining supplies at steeper discounts (by purchasing them in greater volume); sharing resources (such as medical imaging equipment); and achieving the scale necessary to participate in value-based payment programs. These potential efficiencies could in turn benefit patients, for example, if they lead to higher quality care or reduced costs (e.g., if providers share savings through lower prices), and the latter could benefit health plan enrollees more generally to the extent that it leads to lower plan spending and premiums. On the other hand, consolidation often reduces market competition and therefore the pressure on providers to lower prices or invest in quality improvement. Critics have also questioned the extent to which mergers allow providers to operate more efficiently. Efficiencies may depend, in part, on the degree to which providers integrate their operations, which can be complex and may or may not be a priority.

The following discussion describes key findings from the research.

A substantial body of research shows that consolidation has led to higher health care prices, as noted in a 2020 KFF issue brief on provider consolidation. The evidence that consolidation leads to higher prices is strongest for hospitals, though studies that have evaluated physician and hospital-physician consolidation have also tended to find that they are associated with higher prices. Studies that have looked specifically at consolidation among nonprofit hospitals—which account for 58% of all community hospitals—have found price increases as well. A RAND Corporation review from 2022 (which also informs other sections of this brief) found that estimated price increases associated with hospital mergers have ranged from 3 to 65 percent. The large variation in estimated price increases may reflect differences in the types of mergers that were evaluated (e.g., the extent to which they reduced competition), the context of these mergers (e.g., the competitiveness of local insurance markets), and methodology. In addition to increases in the prices that commercial insurers pay providers, consolidation can also lead to higher Medicare reimbursement rates, as the program often provides greater reimbursement for a given service when provided in a hospital outpatient department versus a freestanding physician office (see discussion of site-neutral payment reforms below).

Relatedly, studies have typically found that consolidation leads to higher health care spending, which could increase costs for families, employers, states, and public programs, like Medicare and Medicaid. Several studies have found that consolidation leads to higher spending, which reflects both the price and volume of care. This includes studies evaluating hospital consolidation and hospital-physician consolidation. Only a small number of studies have evaluated physician consolidation, with mixed results. Increases in health care spending can be passed onto health plan enrollees through higher premiums and workers with employer-sponsored insurance through lower wages. Notably, a couple of studies have found an association between consolidation and premium increases, and one study found that hospital mergers led to decreases in wages among non-health care workers with employer health plans.

The evidence on the effect of provider consolidation on the quality of patient care is unclear. The evidence on the impact of horizontal and vertical consolidation on quality has been mixed, as described in a 2020 KFF issue brief and 2022 RAND Corporation review. For example, most of the research on horizontal hospital consolidation has found no difference1 in or a negative impact on quality. Among other analyses, one study found that increased market concentration was associated with higher risk-adjusted one-year mortality rates for heart attacks and another found that hospital mergers were associated with a small decrease in patient experience measures and no changes in 30-day readmission and mortality rates (with inconclusive findings regarding clinical process measures). However, some studies have included mixed or positive findings relating to hospital consolidation. For example, a study funded by the American Hospital Association found that mergers were associated with decreases in 30-day readmission rates but no change in 30-day mortality rates (though an earlier version of the study found decreases in mortality rates as well).

The evidence is also mixed on the effects of vertical hospital-physician consolidation on quality. For example, one fairly recent study found that clinical process and patient experience measures were “marginally” higher for patients when their primary care physician was part of a system, another study found no difference in patients’ 30-day readmission rates when their primary care physician was part of a large system, and a third study found that complications following colonoscopies were higher for patients when their gastroenterologist was part of a system (though the evidence was less clear for clinical process measures).

Interpreting the evidence on quality is further complicated by the fact that there are many dimensions and measures of quality that have been or could be used to assess the effects of consolidation and that it could take time for changes in quality to materialize. Additionally, it is likely that the effects of consolidation vary based on the extent to which providers have integrated their operations and across different patient populations.

5. Mergers between hospitals and health systems can lead to higher prices even when entities operate in different markets

While policymakers and regulators have historically focused on consolidation within the same region, many mergers have occurred between hospitals and health systems that operate in different regions, as discussed in a KFF issue brief, including several multi-billion dollar deals over just the past couple of years. The small number of studies that have focused on cross-market mergers have estimated price increases ranging from 6% to 17%, even though these deals entail hospitals and health systems that are not competing against each other in the same area. There are a few reasons why cross-market mergers might lead to price increases. For instance, a combined health system with providers in, say, different areas of a state may be able to use its dominant position in one market to negotiate higher prices in another when contracting with a given health plan (e.g., a state employee plan with enrollees that reside in several markets). As another example, a large system that, say, acquires a small hospital may have more expertise in bargaining with insurers, which it could use to negotiate for higher prices.

6. The impact of consolidation on the availability of health care services for rural and other underserved patients is unclear

Consolidation could in principle have mixed implications for access to care. For example, it is conceivable that the acquisition of a small, financially struggling, rural hospital by a large health system based in another region could increase the availability of services in the community in some instances and reduce it in others. On the one hand, being acquired could benefit the hospital financially—such as by providing access to a wide range of resources, managerial expertise, and capital—which could help the hospital keep its doors open and maintain or expand the services it offers. On the other hand, the system that acquires the rural hospital may be less responsive to the needs of the local community, such as when deciding whether to close the hospital or to stop offering certain services, such as maternity care (an outcome supported by some research, as described below).

A small number of studies have evaluated the association between consolidation with rural hospital closures and service eliminations, with mixed results. Two studies found that rural hospitals that merged with other hospitals or health systems were more likely to eliminate certain service lines, such as obstetrics care, and another study found that independent hospitals (urban and rural) that joined a health system were more likely to stop offering inpatient pediatric services. One study found that system affiliation was associated with a lower likelihood of closing among rural hospitals with weaker finances but a higher likelihood among those with stronger finances.

A small number of studies have evaluated the association between consolidation and access to care among Medicaid patients, also with mixed results. On the one hand, two studies found that physician practices were more likely to accept Medicaid patients after becoming affiliated with a health system. This may be because the broader system has a commitment or obligation to treat patients regardless of their ability to pay (e.g., for emergency care) or because efficiencies allow providers to treat more patients. On the other hand, one study found that increases in hospital market concentration were associated with fewer Medicaid admissions and a shift in care from nonprofit to public hospitals. This could be because increases in commercial prices resulting from greater market concentration may lead private hospitals to focus more on commercial versus Medicaid patients. Another study found that system affiliation was associated with a decrease in Medicaid as a percentage of all hospital discharges, although that study also found that the number of beds in a hospital or health system was associated with an increase in Medicaid discharges as a share of the total.

A small number of studies have evaluated the effect of consolidation on hospital charity care and total community benefits, with mixed results. For example, one study found no association between the acquisition of independent hospitals and charity care or total community benefit spending overall but a decrease in the latter when focusing on hospitals acquired by an out-of-state system. Another study found that the association of higher market concentration with hospital charity care varied depending on the method used, with an increase under one approach and no difference under another. One study found that higher market concentration was associated with higher income thresholds for charity care eligibility, which effectively increases the number of patients who could qualify for charity care in a hospital.

7. Hospital consolidation can lead to lower wages for some skilled workers, such as nurses, but the broader evidence on employment and compensation effects is limited

Consolidation could in principle have both benefits and drawbacks for health care workers. On the one hand, consolidation could increase the negotiating leverage of hospitals and their ability to extract concessions from workers. For example, in 2023, a coalition of labor unions filed a complaint with the DOJ that UPMC, a large health system in Pennsylvania, had used its market power to suppress the wages of nurses and other health care workers, increase workloads, and restrict the ability of health care workers to seek better employment elsewhere. Mergers could also lead to layoffs, for example, to the extent that providers consolidate their staff and operations. On the other hand, health care workers could benefit from hospital mergers in some scenarios where consolidation allows hospitals to remain open and operate more efficiently. For example, the acquisition of a struggling rural hospital by a health system could help the facility sustain its operations in certain circumstances, which could protect jobs and possibly bolster wages.

A couple of studies have found that hospital consolidation has led to lower wages for some skilled workers, such as nurses, though the implications of other studies on health care worker wages are less clear. For example, one study found that hospital mergers were associated with lower wages for nurses and pharmacy workers and for skilled nonmedical workers following mergers that caused large increases in market concentration (but not for unskilled workers). Research from the Center for Economic and Policy Research also found that increases in hospital market concentration were associated with lower wages for nurses in small metropolitan statistical areas. An earlier study did not find consistent evidence when evaluating nurses’ wages but did find that hospital mergers in California were associated with greater work effort (as measured by patient caseload). A small number of studies that looked more broadly at the financial impact of consolidation, including average compensation across all hospital workers, have produced mixed results.

Some studies find that hospital consolidation has led to reductions in staffing, though others have not, and the evidence is unclear on whether mergers avert closures, which could preserve jobs. A small number of studies have analyzed the effects of hospital consolidation on employment, with some finding an association with reduced staffing levels. For example, one study evaluating independent hospitals in New York found an association between joining a system and a reduction in employment, especially among employees with overhead and support functions. However, other studies have found no differences or inconsistent or unclear results. Additionally, as noted above, there is no clear evidence regarding the effect of mergers on hospital closures. If mergers lead to efficiencies that prevent closures, they may help preserve jobs.

8. The FTC, the DOJ, and state antitrust agencies each play a role in challenging consolidation and other potentially anticompetitive practices

Federal and state antitrust agencies each play a role in challenging consolidation and other potentially anticompetitive practices of health care providers and other businesses, as described in a KFF issue brief. At the federal level, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) share responsibility for enforcing federal antitrust laws, including the Sherman Act, the Clayton Act, and the FTC Act. State attorneys general (AG) offices also have the authority to bring action under federal antitrust law, as well as under state statutes, which sometimes expand upon federal law. Antitrust agencies challenge mergers, acquisitions, and other practices that may hinder competition (such as the use of anticompetitive contract clauses). They do so to promote competitive markets, often for the benefit of consumers (such as patients and health plan enrollees).

There are at least a few challenges that may limit the ability of the federal government and states to foster competitive provider markets through antitrust enforcement:

- It is difficult to break up mergers after they have already occurred, and many provider markets are already highly concentrated. Breaking up a merger after providers have already consolidated can be difficult. At the same time, regulating the behavior of merged providers—such as through restrictions on the prices they charge—may be difficult to monitor and enforce on an ongoing basis.

- Some regions cannot support competitive provider markets. For instance, rural communities may not have enough residents to support several providers that offer the same service.

- Antitrust litigation can be complex and expensive. Without adequate funding, it may be impractical to challenge a large number of provider business practices that raise anticompetitive concerns.

- Antitrust agencies may have difficulty staying ahead of market trends. For example, it could take time for the government to develop strong guidelines for challenging vertical or cross-market mergers and to accumulate enough evidence to convince courts that these practices harm competition. In the meantime, these mergers will likely continue.

- The benefits of competitive provider markets for individuals with health insurance will depend in part on the competitiveness of health insurance markets. One study estimated that most MSAs (57%) had highly concentrated insurance markets in 2016. When insurance markets are not competitive, cost savings from competitive provider markets might not be fully passed along to consumers.

The FTC and DOJ have recently signaled an interest in expanding their scrutiny of different types of mergers. For example, in December 2023, the agencies released updated merger guidelines that indicate that they may challenge a broader range of deals. Among other changes, the guidelines expand the definition of highly concentrated markets, rely on a lower threshold for identifying large changes in market concentration, consider the combined effect of a series of acquisitions (e.g., of a health system acquiring several small physician practices over time), add an explicit discussion of the agencies’ views on how workers may be negatively impacted when their employers merge, and touch on cross-market mergers.

The FTC and DOJ have also indicated an interest in challenging provider acquisitions by private equity firms and private payers. For instance, the agencies, along with HHS, specifically mentioned these types of entities in a March 2024 request for information on the effects of transactions involving health care providers and related products and services. Further, in September 2023, for the first time, the FTC challenged a common strategy of private equity firms that entails amassing market power through a series of physician practice acquisitions.

Policymakers have expressed interest in aligning Medicare reimbursement rates for outpatient services across care settings through “site-neutral payment reforms,” which could directly lower program costs and reduce the incentive for hospitals to buy up physician practices. Under current payment rules, Medicare reimbursement is often higher for a given outpatient service when provided in a hospital outpatient department versus a freestanding physician office or ambulatory surgical center. Two studies have found that these payment differences are associated with an increase in hospital-physician consolidation, which can allow providers to bill Medicare at higher rates.

Through legislation and rulemaking, Medicare has aligned payments for office visits across freestanding physician offices and off-campus hospital outpatient departments—which often resemble physician offices—as well as for other services for relatively new off-campus facilities. Policymakers have considered other site-neutral reforms with varying scope that would extend to additional sites of care and services. Proponents of these reforms assert there are no grounds to pay different amounts for the same service based on site of care (physician office or outpatient hospital department) while hospitals and other opponents counter that patients treated in hospital outpatient settings have greater needs than patients in physician settings and that their cost structure justifies higher payment rates.

10. Policymakers have considered a number of options to increase the competitiveness of provider markets

Several policies have been proposed to rein in provider consolidation or increase the competitiveness of provider markets in other ways:

- Strengthen antitrust enforcement. This approach would make it easier for the FTC and DOJ to enforce antitrust law. Specific policies include: requiring more providers to report planned mergers, lowering the legal standards by which mergers are deemed anticompetitive, and mandating that providers receive approval from the government before merging. Other proposals to strengthen antitrust enforcement include: eliminating state Certificate of Public Advantage (COPA) laws (which some states use to shield mergers from federal antitrust challenges in exchange for state regulation), increasing the scope of antitrust law (such as by giving the FTC full authority to regulate nonprofit providers and outlawing anticompetitive contracting clauses), and providing greater resources to agencies that enforce antitrust law.

- Reduce incentives for health care providers to consolidate. This could include site-neutral payment reforms (as described above), changes to the 340B program (which currently allows certain providers acquired by a 340B entity to purchase drugs at a substantial discount), and efforts to reduce the administrative burden of government regulations on providers (which may incentivize small practices that have difficulty shouldering these requirements to merge with other providers).

- Increase price transparency. Greater price transparency could help patients, plans, and employers shop for health care providers (e.g., to receive care from or include in provider networks) and may in turn encourage greater competition among providers. As discussed in a KFF issue brief, information about hospital and other health care prices remains elusive, despite recent federal transparency rules.

- Allow more providers to enter the market. This could include reforming state Certificate of Need (CON) statues (which can be used to limit, for example, the construction of new health care facilities) and scope of practice laws (which regulate what work various health care professionals, such as nurse practitioners, are allowed to perform).

Each of these proposals would involve tradeoffs that would be important to consider.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.