Most Antiretrovirals Covered by Medicare Part D (as of 2017) Are Brand-Name, Single Source Medications

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Drug price concerns in the U.S., including for antiretrovirals, the mainstay of HIV treatment and, increasingly prevention, have prompted the introduction of several policy proposals. One proposal would require manufacturers to provide a rebate to Medicare if prices increase faster than inflation. As a drug class, ARVs lack competition in the U.S. market and few generic options are available, leading to particular concerns over their pricing. We assessed list price changes between 2016 and 2017 for ARVs under Medicare Part D, which is required to cover all or substantially all ARVs. During this period, 48 ARVs were covered by Part D, 38 of which were brand medications and 30 were single source.

According to our analysis:

These findings suggest that current proposals that seek to control Part D prices relative to inflation could yield savings.

Ongoing concerns about prescription drug pricing and affordability in the United States have prompted the introduction of policy proposals from the White House, members of Congress, and presidential candidates. Some of these proposals would require drug manufacturers to pay a rebate to the federal government if their prices for drugs covered under Medicare Part B and Part D increase by more than the rate of inflation. Indeed, a recent KFF analysis found that list price increases for more than half of Medicare Part D drugs exceeded inflation in 2017, in some cases by a substantial margin, suggesting opportunities for significant savings under these plans.

We used the same methodology to assess price changes for antiretroviral medications (ARVs) under Part D, which is required to cover all or substantially all ARVs as one of six protected drug classes. ARVs are the mainstay of HIV treatment and, increasingly prevention. National treatment guidelines recommend initiating ARV treatment upon an HIV diagnosis; for those at high risk, pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, with ARVs is recommended to prevent HIV acquisition.

While only a small share of people in the U.S. have HIV or are on PrEP, spending on ARVs has an outsized impact on prescription drug spending across payers. In addition, concerns have been raised about ARV drug pricing and affordability specifically, where list prices for a typical recommended HIV treatment regimen could range from $22,000 to $38,000 per year. High prices are, in part, driven by the lack of manufacturer competition and minimal availability of generic substitutes within the U.S. ARV market, the very types of drugs targeted by several of the prescription drug policy proposals.

To assess changes in the list prices of ARVs covered by Medicare Part D relative to inflation, we used data from the CMS Medicare Part D Spending Dashboard to identify ARVs used in the two most recent years available (2016 and 2017). List price changes were measured by one-year (2016-2017) changes in average spending per dosage unit amounts reported. Our analysis is based on unit prices that do not reflect manufacturer rebates and discounts to plans, which are considered proprietary and therefore not publicly available (the major proposals being considered are not based on post-rebate prices). Inflation was measured over the same period using the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers (CPI-U), which was 1.7% between 2016 and 2017. A full methodology can be found here.

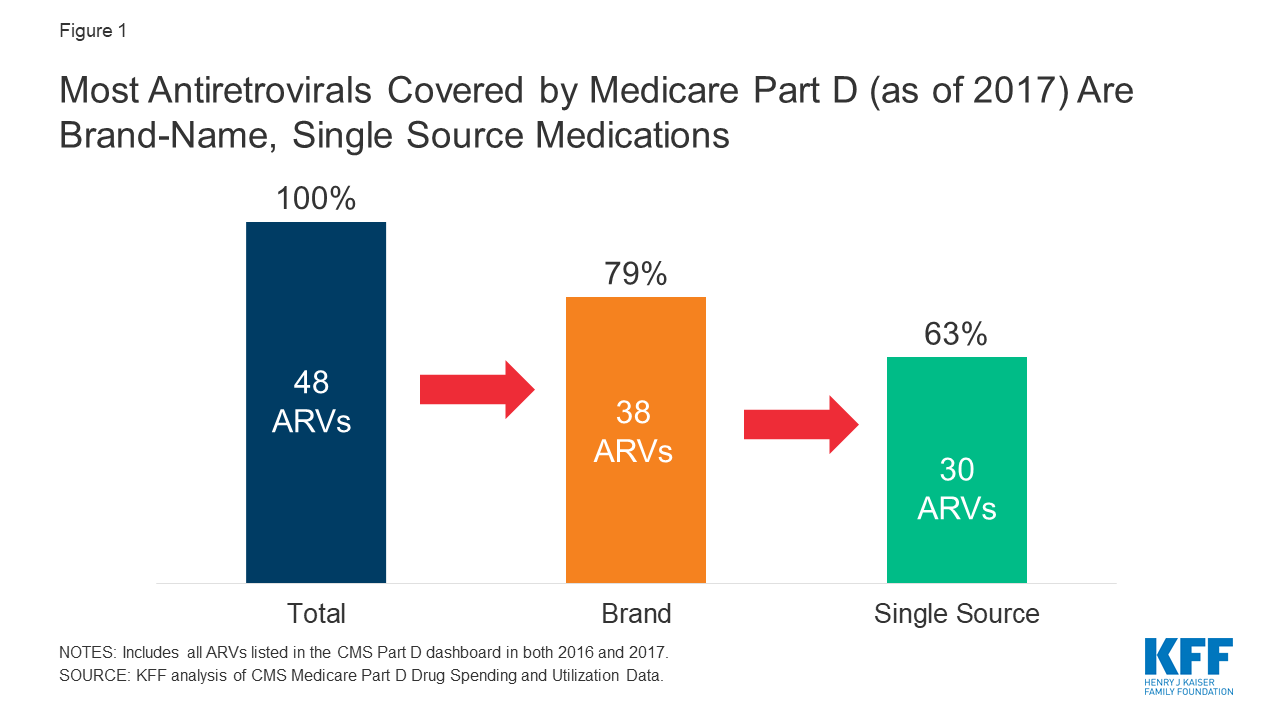

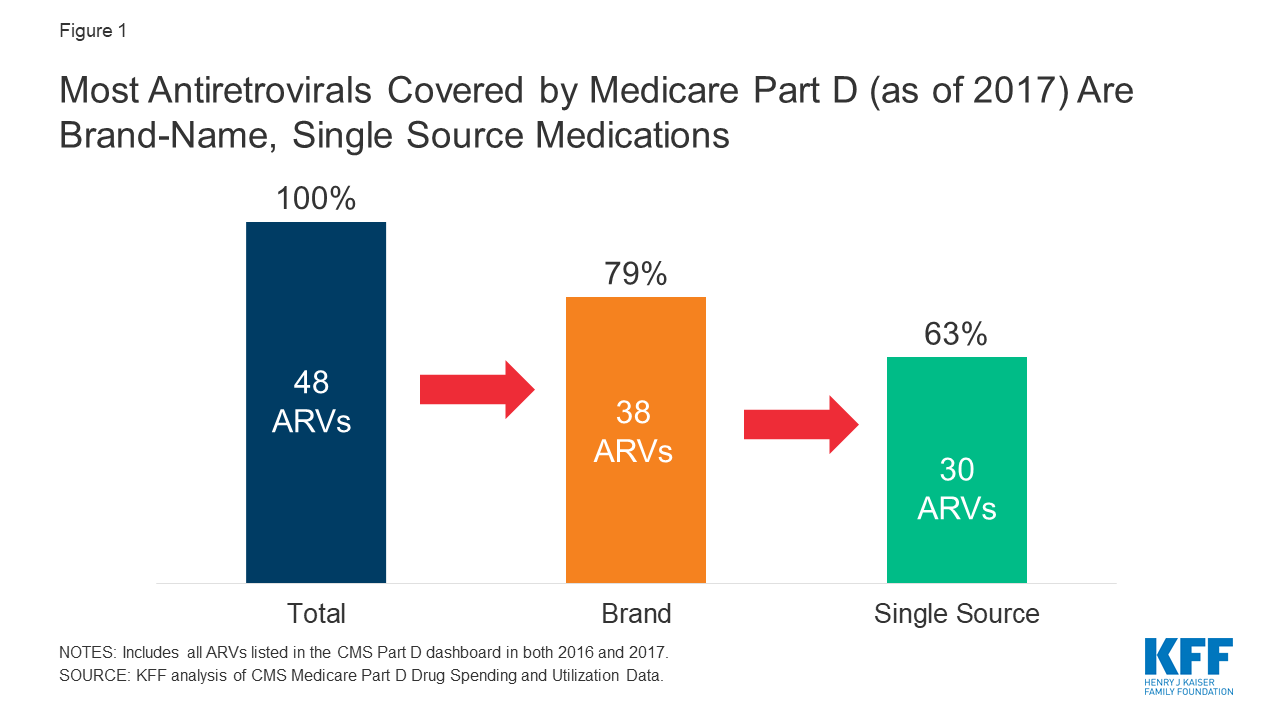

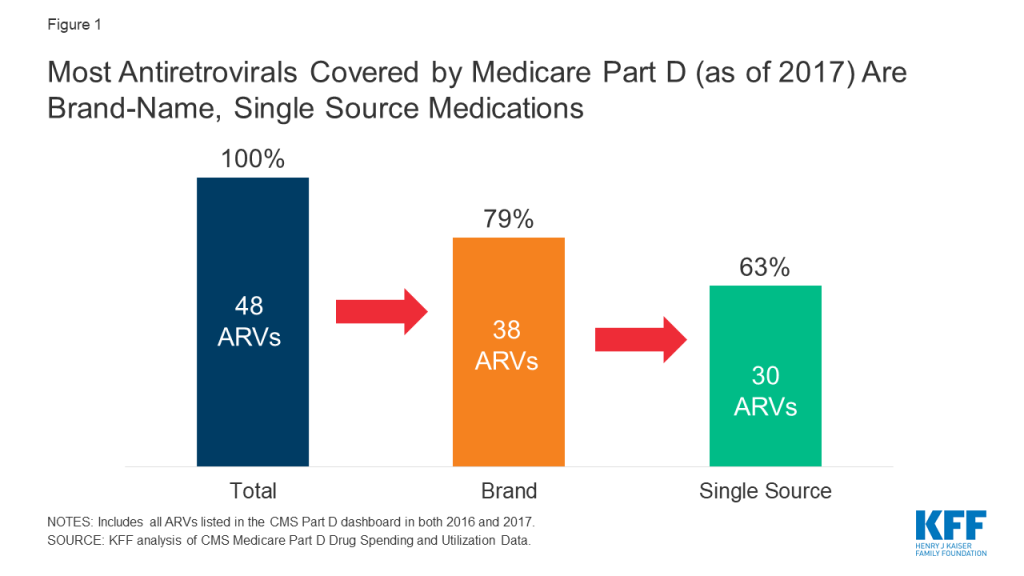

The 2019 Medicare Part D Spending Dashboard includes 48 antiretrovirals that were utilized in 2016 and 2017, including both brand and generic drugs (see Table 1). Most ARVs (38 or 79%) were brand medications and almost two-thirds (30 or 63%) were single source, meaning they had no generic alternative (see Figure 1).

Of the 48 ARVs reported in the 2017 Part D dashboard, almost three-quarters (35 drugs or 73%) had list price increases that exceeded inflation between July 2016 and July 2017 (1.7%). This compares to 60% of Part D medications overall. Most of these price increases were more than 3 times the rate of inflation. Almost all drugs with price increases exceeding inflation were brand-name medications (32), and the vast majority were single source (27). Of the remaining ARVs, 10% (or 5 drugs) had list price increases below inflation between 2016 and 2017, and 17% (8 drugs) had price decreases over this period. All 8 of the ARVs with price decreases were available as generics (see Figure 2).

We examined price increases for ARVs with the highest spending and utilization among Part D enrollees. Among the 10 ARVs with the highest Part D spending in 2017, all were brand-name, single source medications, and all had list price increases exceeding inflation by at least 5 percentage points (see Figure 3). For instance, Genvoya, the ARV with the highest Part D spending, had a price increase of 7.4%. Triumeq, the ARV with the second highest spending, had a price increase of 9.6%, nearly six times the rate of inflation. Truvada, used for HIV treatment as well as PrEP, had the fourth highest Part D spending, and a list price increase of 7.5%. Until 2019, Truvada was the only ARV approved for PrEP.

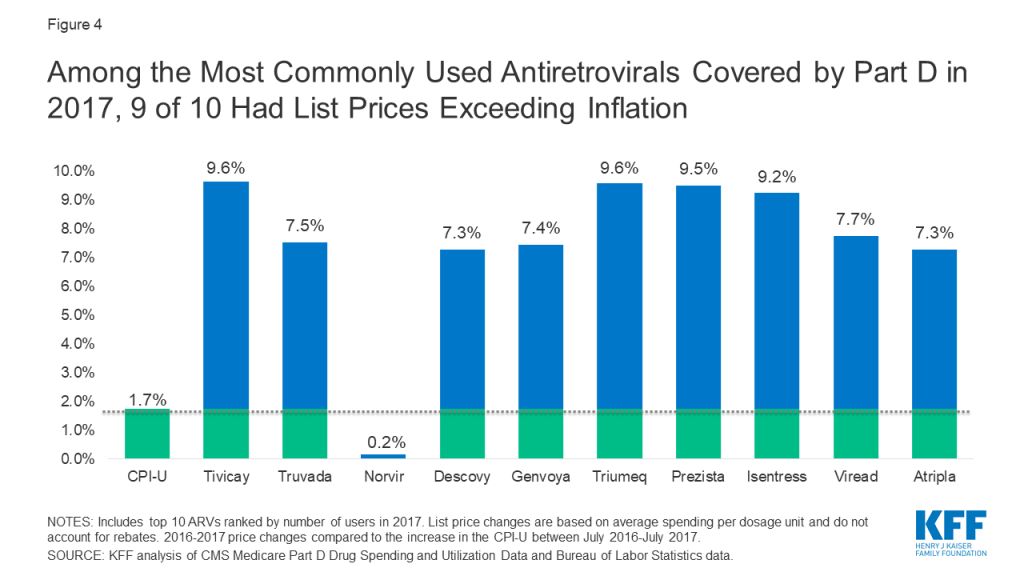

Among the top 10 most commonly used ARVs, 9 had list price increases exceeding inflation by at least 5 percentage points and, as with spending, all were brand-name, single source drugs (see Figure 4). The top two most commonly used ARVs – Tivicay and Truvada, each with over 36,000 users in 2017 – had list prices that increased by 9.6% and 7.5%, respectively.

As with Medicare Part D drugs overall, the majority of ARVs had price increases that exceeded the rate of inflation by several percentage points. Moreover, reflecting the lack of competition within the U.S. ARV market, most of these were brand-name, single source medications, including those with the highest spending and greatest utilization, the very types of medications targeted by current policy proposals. These findings suggest that such proposals could yield savings for public and private payers and for patients. However, proposals that place limits on year-to-year drug price increases may incentivize manufactures to introduce newer medications at higher prices. This could present particular challenges in the case of HIV, where several newer treatment and prevention regimens are on the near-term horizon.

| Table 1: List Price Changes Between 2016-2017 for ARVs by Total Medicare Part D Spending in 2017 | |||

| Drug Name | Total Part D Spending in 2017 | Number of Users in 2017 | 2016-2017 List Price Change |

| Genvoya | $689,941,011.34 | 28,632 | 7.4% |

| Triumeq | $650,941,450.22 | 27,561 | 9.6% |

| Tivicay | $518,431,674.93 | 36,611 | 9.6% |

| Truvada | $416,800,910.94 | 36,552 | 7.5% |

| Atripla | $415,313,758.64 | 18,148 | 7.3% |

| Descovy | $404,070,231.27 | 31,533 | 7.3% |

| Prezista | $350,738,609.34 | 27,211 | 9.5% |

| Isentress | $320,942,015.53 | 25,667 | 9.2% |

| Odefsey | $228,725,946.87 | 10,664 | 7.2% |

| Prezcobix | $223,824,222.87 | 16,153 | 9.0% |

| Stribild | $171,008,928.08 | 7,411 | 8.4% |

| Viread | $166,748,054.55 | 20,409 | 7.7% |

| Reyataz | $145,194,479.40 | 11,682 | 6.6% |

| Complera | $109,054,960.06 | 5,263 | 8.3% |

| Norvir | $100,716,172.19 | 35,212 | 0.2% |

| Intelence | $99,729,416.45 | 9,108 | 10.2% |

| Sustiva | $57,430,302.28 | 6,195 | 7.5% |

| Selzentry | $49,645,406.08 | 3,282 | 9.4% |

| Kaletra | $38,421,347.87 | 4,721 | 7.1% |

| Abacavir-Lamivudine | $36,163,620.28 | 9,471 | -30.2% |

| Edurant | $33,470,096.30 | 3,957 | 9.1% |

| Evotaz | $32,508,946.37 | 2,426 | 7.4% |

| Epzicom | $26,139,505.74 | 4,150 | -2.0% |

| Lexiva | $17,792,125.43 | 1,541 | 9.1% |

| Abacavir | $16,159,350.36 | 8,022 | -5.8% |

| Lamivudine | $12,136,669.35 | 9,734 | -7.3% |

| Abacavir-Lamivudine-Zidovudine | $10,164,840.09 | 973 | 3.2% |

| Emtriva | $9,769,395.38 | 2,828 | 0.2% |

| Lamivudine-Zidovudine | $8,943,870.54 | 4,035 | -20.1% |

| Nevirapine ER | $8,783,702.01 | 2,042 | -10.1% |

| Viracept | $7,356,137.42 | 799 | 8.9% |

| Fuzeon | $5,917,901.94 | 198 | 6.5% |

| Invirase | $3,824,859.01 | 350 | 6.6% |

| Aptivus | $2,780,380.01 | 196 | 7.8% |

| Combivir | $1,129,748.72 | 165 | 2.0% |

| Nevirapine | $956,975.66 | 2,585 | 1.4% |

| Didanosine | $885,882.06 | 522 | 10.8% |

| Ziagen | $861,764.65 | 331 | -6.5% |

| Trizivir | $799,844.30 | 94 | 3.6% |

| Viramune XR | $757,400.11 | 212 | 7.3% |

| Zidovudine | $562,555.68 | 1,857 | -0.5% |

| Crixivan | $510,444.65 | 145 | 0.2% |

| Epivir | $437,552.20 | 466 | 58.3% |

| Viramune | $437,525.85 | 86 | 5.4% |

| Stavudine | $310,975.88 | 531 | 7.0% |

| Tybost | $182,986.76 | 163 | 6.7% |

| Rescriptor | $104,025.14 | 24 | 7.3% |

| Videx EC | $8,506.46 | — | 0.6% |

| NOTE: List price changes are based on average spending per dosage unit and do not account for rebates. – indicates data not available due to small sample size.SOURCE: KFF analysis of CMS Medicare Part D Drug Spending and Utilization Data, 2016-2017. | |||

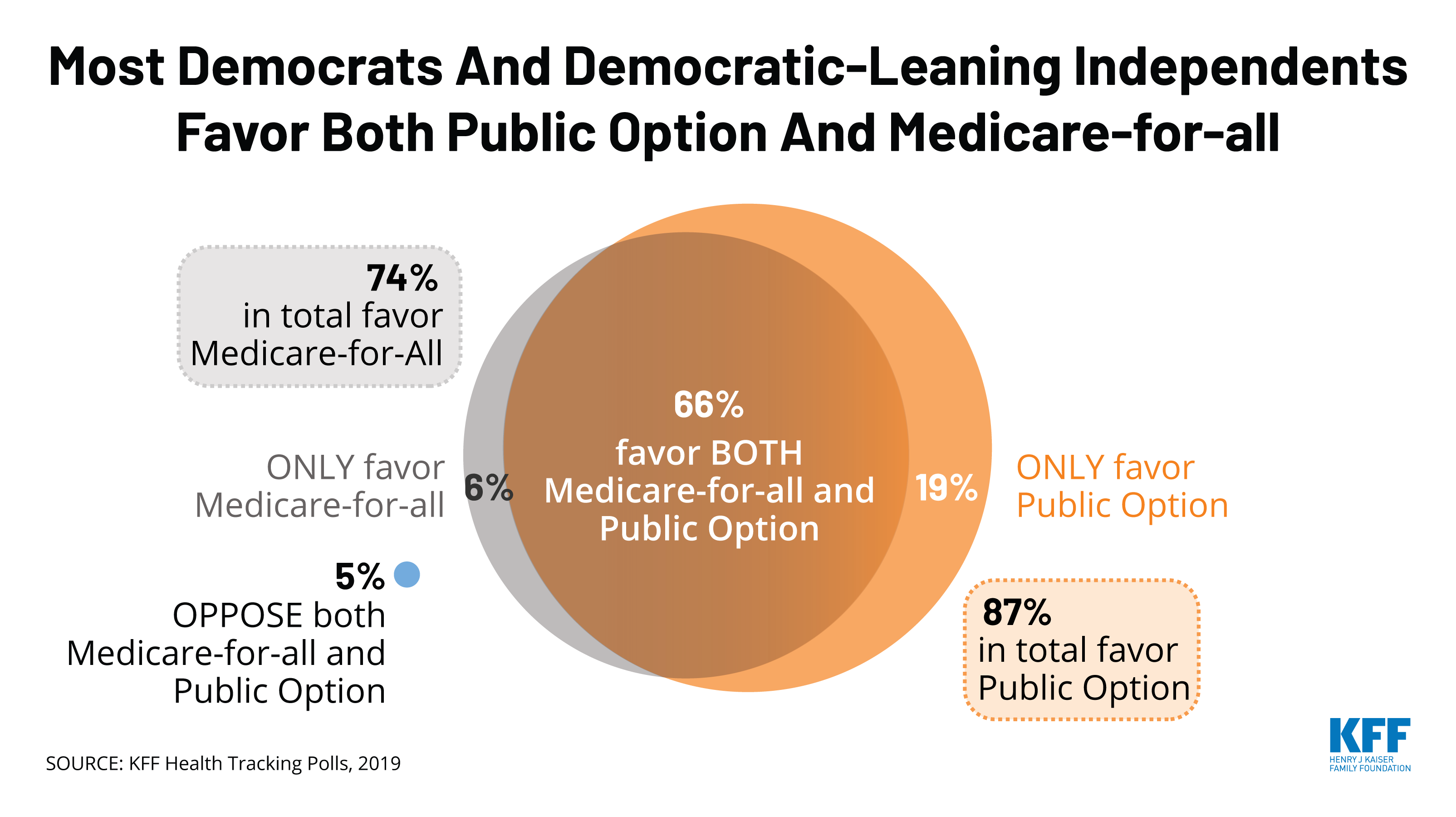

As the Democratic presidential candidates continue to debate and campaign for their party’s 2020 nomination, health care ranks high on the list of issues that Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents want the candidates to discuss. KFF offers independent, non-partisan policy analysis, polling and other research and has experts who can provide context, explain trade-offs and provide key data points on health care issues that may arise in the debates and broader campaign. Some key resources:

Medicare-for-all and Other Proposals to Expand Public Coverage

Affordable Care Act and Protections for Pre-Existing Conditions

Prescription Drug Costs

Health Costs and Surprise Medical Bills

Abortion and Other Reproductive Health Issues

Medicaid and the Uninsured

Climate Change

If you have questions about any of these resources or want to talk to a KFF expert, please contact Rakesh Singh, Craig Palosky, Chris Lee or Nikki Lanshaw for assistance.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) continues to promote state adoption of work and reporting requirements as a condition of Medicaid eligibility for certain nonelderly adults, although several such waivers have been set aside by federal courts. While most Medicaid adults are already working, some states and health plans have developed voluntary work support programs for nonelderly adults who qualify for Medicaid through non-disability pathways. These programs offer services that support work without conditioning Medicaid eligibility on having a job. This brief examines opportunities for and limitations on federal and state support of such programs, highlights several state and health plan initiatives, and explores their common themes. Key findings include the following:

KFF analysis shows that 63% of Medicaid adults1 are already working, many in jobs that do not offer health insurance, and that those who are not working often face barriers to employment.2 Caregiving responsibilities, illness or disability, and school attendance are the most common reasons that Medicaid enrollees report for not working, while those in better health and with more education are more likely to be working. Among Medicaid adults who are working, the majority (53%) work full-time for the entire year. These enrollees may be eligible for Medicaid in expansion states if they are working low-wage jobs, while those working in non-expansion states could earn enough to become ineligible for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for Marketplace subsidies (which require income of 100% to 400% of the poverty level), while also not necessarily receiving health coverage through their jobs. Only about four in ten working Medicaid adults have access to employer-sponsored insurance.

CMS issued guidance in January 20183 for state Medicaid waiver proposals that condition Medicaid eligibility on work and reporting requirements, and several states have received approval for or are pursuing these waivers.4 The administration says that such policies are designed to address health determinants, such as employment, to improve health outcomes.5 The waivers seek to promote work by making individuals’ health coverage contingent on meeting certain requirements – like reporting minimum monthly work hours – versus supporting employment through voluntary efforts that focus on identifying barriers to work and facilitating links to services that address those barriers. The January 2018 CMS guidance notes the importance of employment supports while stating that such support services are not eligible for federal Medicaid funds.

The experience of Arkansas, the first state to implement a Medicaid work requirement, reveals widespread coverage losses and little measurable increase in employment as a result of the requirement. The work requirement phased in beginning in June 2018, and state data revealed that, by December 2018, over 18,000 Medicaid enrollees had been disenrolled6 from the program for failure to comply with the new requirements, with most of this coverage loss resulting from failure to report activities. By February 2019, only 11% of those enrollees had regained coverage in Medicaid. While the state did not track whether enrollees began work activities in response to the requirement, an independent study found no significant change in employment in response to implementation of the requirement.7 Arkansas’s waiver that authorizes its work requirement was set aside by a federal court in March 2019, suspending the requirement’s implementation; an appeal is currently pending.

Medicaid supports employment by providing affordable health coverage, which helps low-wage workers get care that enables them to remain healthy enough to work. Research has shown that access to affordable health insurance and care promotes individuals’ ability to obtain and maintain employment. For example, in studies on the effects of Medicaid expansion in Ohio and Michigan before CMS approved work requirements in these states, previously unemployed individuals reported that Medicaid enrollment made it easier for them to seek employment, while employed individuals reported that enrollment allowed them to perform better at work or made it easier to continue working.8 A study of Montana’s Medicaid expansion, including the state’s voluntary Medicaid work support program (HELP-Link), found an increase of four to six percentage points in labor force participation among low-income, non-disabled adults ages 18-64 following expansion, compared to higher-income non-Medicaid Montanans and to the same population in other states.9

Medicaid also supports work by providing eligibility pathways for individuals with disabilities and home and community-based services (HCBS) that support employment and target barriers to work.10 Under Medicaid buy-in programs, states can elect to cover people with disabilities who choose to work, supporting their participation in the workforce without carrying the risk of coverage loss. The median income limit for this pathway is 250% FPL, well above the income limit for other coverage groups.11 HCBS help individuals with disabilities with self-care and household activities to enable them to live independently in the community. These services can support work for individuals with disabilities who choose to work by addressing physical, mental health, or cognitive needs that create barriers to employment.12 States can also provide voluntary supported employment services to targeted Medicaid populations, such as pre-employment services (e.g., employment assessment, assistance with identifying and obtaining employment, and/or working with employer on job customization) and employment sustaining services (e.g., job coaching and/or consultation with employers).13

State Medicaid programs have limited flexibility to support employment for nonelderly Medicaid adults eligible through non-disability pathways. The transitional medical assistance (TMA) pathway allows low-income parents who lose eligibility for cash assistance due to earned income to remain eligible for Medicaid for at least six months and, at state option, up to a year if their earnings increase through work and exceed the Medicaid eligibility threshold. Although states are not able to use federal Medicaid funds to pay the direct costs of non-medical services that address social needs (e.g., housing, food assistance, employment supports), states can link enrollees to social service programs through case management or targeted case management benefits. In addition, many states that contract with Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) to deliver services to enrollees are leveraging MCO contracts to promote strategies to address enrollee social needs. According to a KFF survey of state Medicaid programs14 released in October 2019, about three-quarters of the 41 managed care states will require MCOs to screen enrollees for social needs, provide enrollees with referrals to social services, or partner with community-based organizations in FY 2020. Under federal Medicaid managed care rules, health plans also have some flexibility to pay for non-medical services directly, but it is currently unclear how frequently plans engage in funding these types of activities, as states have provided little guidance to health plans in this area to date.15 ,16

In the spring of 2019, CMS released further guidance17 on implementing, monitoring, and evaluating Medicaid work requirement waivers, which contains strategies that states interested in developing voluntary work support programs could adopt as well. The guidance includes a detailed implementation plan template18 with a section on establishing beneficiary supports and modifications, requiring states to describe in detail how they will provide supports to beneficiaries (e.g., transportation, child care, language) to ensure that they are able to meet work requirements. Although CMS developed the guidance for states pursuing policies to condition coverage on meeting work and reporting requirements, it provides numerous examples of practical strategies that state Medicaid programs interested in developing voluntary work support initiatives could implement as well.

While most Medicaid adults are already working, some states have launched initiatives to support employment for Medicaid enrollees who qualify for Medicaid through non-disability pathways, without making employment a condition for eligibility. While states like Arkansas and Indiana offered voluntary employment referral programs for Medicaid expansion enrollees before implementing work requirements, those programs relied on general enrollee notices rather than targeted outreach and follow-up and saw limited participation.19 Other states have taken a more proactive approach to maximize the success of their voluntary work support programs, incorporating intensive targeted outreach and case management services. These states — Montana, Louisiana, and Maine — provide examples of work support activities that provide Medicaid expansion enrollees with targeted employment-related services and trainings and/or connect them with appropriate existing state and federal workforce programs. In addition to state agencies, some MCOs have developed work support initiatives in an effort to address their members’ social determinants of health.

Montana provides a leading example of a state that supports employment for Medicaid enrollees without conditioning eligibility on work. While Montana did submit a proposed work requirement waiver amendment to CMS in August 2019 as a condition of continuing its Medicaid expansion — and has since delayed the implementation of the requirement20 — the state has several years of experience with providing voluntary work supports to expansion enrollees with identified barriers to work. As part of the 2015 “Health Economic Livelihood Partnership” (HELP) legislation that established the state’s ACA Medicaid expansion, Montana created “HELP-Link,” a free voluntary workforce support program for eligible expansion adults. HELP-Link, which launched on January 1, 2016, provides individualized career planning and training assistance, and participation in the program may help individuals who fall behind in paying Medicaid premiums to maintain coverage, as nonpayment can otherwise result in disenrollment.21 Montana’s stated objective for HELP-Link is to “improve the employment and wage outcomes of individuals enrolled in certain types of Montana Medicaid, with the goal of reducing clients’ reliance on Medicaid for health insurance and improving Montana’s workforce.”22

Since states cannot receive federal Medicaid funds for employment support services for Medicaid enrollees, Montana administers the HELP-Link program with state funds. The state’s Department of Labor and Industry (MTDLI) operates the HELP-Link program in partnership with Montana’s Department of Health and Human Services. Montana allocated state workforce training funds specifically for HELP-Link, which offers more intensive one-on-one services and case management than other MTDLI programs. In serving Montana Medicaid enrollees found eligible for HELP-Link, the state often leverages other federally funded workforce programs to help stretch HELP-Link dollars. Of the roughly 32,000 Montana Medicaid expansion adults who received career or workforce training services through an MTDLI program from the launch of HELP-Link through June 30, 2019, 4,257 people received services with targeted HELP-Link funds.23 HELP-Link clients can also co-enroll in multiple workforce programs. The state appropriated $1.8 million for HELP-Link for the first year and a half of the program, spent $1.6 million in SFY 2018, and allocated almost $889,000 for SFY 2019, supplementing that initial SFY 2019 allocation with $50,620 in additional state funds.24 Of total HELP-Link spending, 53% went directly to participants and 32% to case management and other client services.25 HELP-Link was initially a pilot program scheduled to expire in July 2019, but the 2019 state legislation that required submission of the work requirement waiver appropriated $3.5 million to extend the program through SFY 2021, although some of this funding will be used to create another state workforce program.26

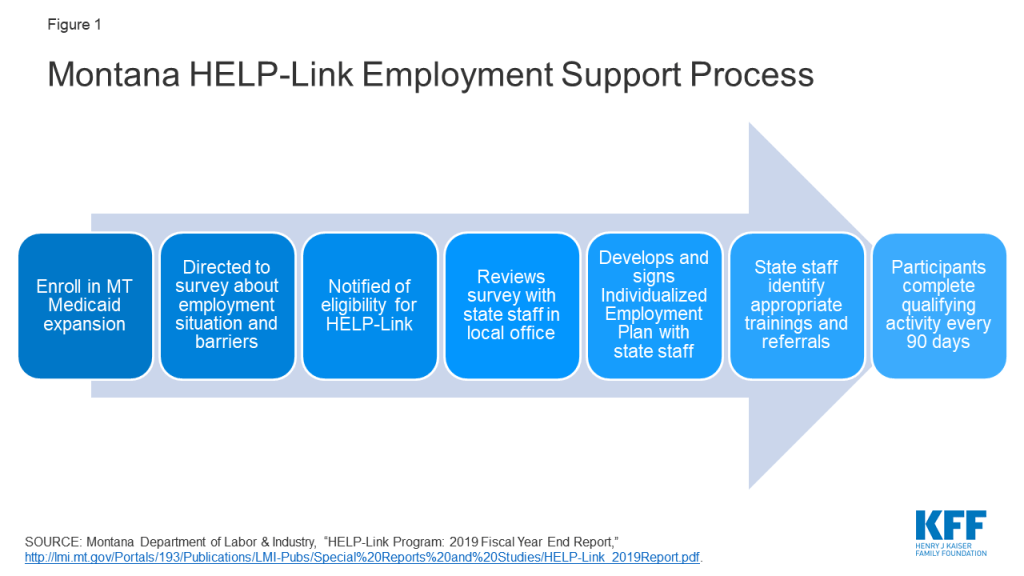

The HELP-Link program uses a screening survey, employment support services, and referrals to identify enrollee goals and needs and connect them to the appropriate resources (Figure 1). As soon as Montanans enroll in Medicaid expansion, they are automatically directed to a state website to complete a survey about their employment status and barriers to work and invited to participate in state workforce programs. Individuals can also complete the survey in person in a Job Service Montana office. If found eligible for HELP-Link, individuals must meet in person with Job Service Montana staff to develop an Individualized Employment Plan that serves as a step-by-step checklist that can assist HELP-Link participants in achieving their employment goals. The state acknowledges that this in-person interview can be a barrier to participation for individuals who live in rural or reservation areas or far from a Job Service office, although the state notes that participants may request a phone appointment if “extenuating circumstances” prevent an in-person visit.27

HELP-Link assists participants across five domains, which require different levels of resources. The domains include employment services and career planning (e.g., resume assistance, mock interview practice, local job opportunity information); workforce and educational training; work-based learning (including wage subsidies for on-the-job training); supportive services (financial assistance to address specific barriers); and referrals to other service providers (e.g., for needs related to transportation, childcare, or domestic violence). Most HELP-Link participants receive less resource-intensive career services, which could include referrals to other federal workforce programs, while a smaller group of participants receive support for educational and job training programs, which could take several years to complete. The level of HELP-Link funds required for different types of services varies by resource intensiveness. For example, the majority of SFY 2019 HELP-Link funding went to employment-related training and support ($1,703 per client for 250 clients), while the state spent $176 per participant on case management services for 1,159 participants. Montana has noted that this tiered support system, in which individuals with greater need receive more intensive program services, may serve as a cost-effective method of operation.28

To address participant barriers to work such as lack of transportation, housing, internet access, or childcare, Montana Job Service staff can use HELP-Link funds both to meet these needs directly and to refer participants to other state and federal programs or community-based organizations that provide appropriate resources. HELP-Link stresses the provision of customized and flexible support to its participants, tailored to meet individual needs. For example, HELP-Link funds can cover qualifying individuals’ enrollment in educational or training programs that can help them attain credentials that further their careers. HELP-Link funds can also cover supportive services, providing financial assistance to help resolve barriers to employment (e.g., to pay for gas, auto repairs, or job-related equipment). To remain eligible to receive work supports through HELP-Link after signing their employment plans, participants must complete a qualifying workforce planning, training, or job search activity every 90 days.

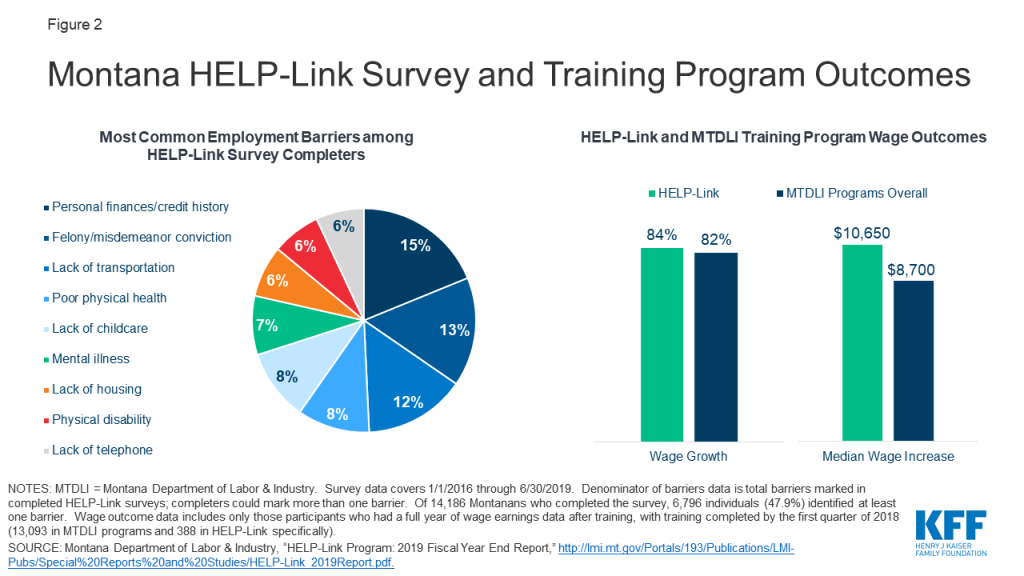

Outcomes from the first two years of HELP-Link implementation, alongside other MTLDI programs, reveal several common barriers to work, along with high rates of participant employment and wage growth after receipt of HELP-Link training (Figure 2). The most common barriers to employment for those individuals who completed the survey included personal finances and credit history; felony or misdemeanor conviction; lack of transportation, childcare, housing, or telephone access; poor physical health; mental illness; and physical disability. Because of limited HELP-Link funds, some Medicaid expansion enrollees received employment services through HELP-Link specifically, while others participated in other MTDLI workforce development programs. Wage outcomes for enrollees who participated in training activities varied according to whether the individuals received HELP-Link-funded training or training funded through MTDLI programs more broadly.29 Large shares of both those in MTDLI workforce programs overall and those who received the additional training resources and services available under the HELP-Link program saw wage growth among employed participants (82% and 84%, respectively). However, those receiving HELP-Link-funded services saw higher median wage increases a full year after completing training ($10,650, versus $8,700 for those participants in MTDLI programs overall).30 These outcomes include only participants who completed training by the first quarter of 2018 (388 in HELP-Link and 13,093 in MTDLI workforce training programs) and had a full year of wage earning data available after completion.31 The most common occupations pursued by HELP-Link participants include truck drivers, registered nurses, and personal care and service workers.

On a smaller scale than Montana, Louisiana has taken a local approach to voluntary Medicaid enrollee work supports. After Louisiana rejected legislation to condition Medicaid eligibility on work, the state invested in a pilot program to link certain Medicaid expansion enrollees with targeted work training programs through Louisiana Delta Community College (LDCC).32 Under the program, LDCC identifies a subset of unemployed and underemployed Medicaid recipients living in Ouachita Parish whom it considers able to benefit from the program, and LDCC and the Louisiana Department of Health (LDH) collaborate to conduct outreach to those individuals. Individuals who accept the invitation to enroll in the pilot program then participate in an intake process to identify work experience and interests, which leads to the formation of an individualized participant plan with the assistance of designated pilot staff members. Participants are then matched with tailored support services and enroll in select work training programs with assignment to an LDCC mentor. Support services may include job readiness and job search resources, while available training programs include those for occupations such as certified nurse assistants and environmental services technicians. The time that participants have to complete their programs will depend on the courses of study that they select.33 Public state documents do not specify the source of funding for this program, but the governing legislation establishes that a partnership of state agencies, led by the executive director of the Louisiana Workforce Commission, will design and administer the program.34

Maine provides another example of a state that has chosen to emphasize vocational training and workforce supports rather than impose a work requirement as a condition of eligibility in its Medicaid program. After Maine’s voters approved a 2016 ballot initiative to expand Medicaid (which did not include a work requirement), the governor in office at the time refused to adopt it and instead submitted a waiver request to CMS seeking approval of a work requirement. Once the current governor took office in early 2019, she adopted the voter-approved Medicaid expansion and chose not to accept the federal government’s terms for a work requirement,35 electing instead to increase the accessibility and use of existing state and federal programs devoted to work training.

Maine’s work support activities for both expansion and non-expansion Medicaid enrollees include collaborating with other state agencies and connecting enrollees to federal programs that address their employment and social needs.36 At a high level, the state’s governor directed the Commissioners of Labor and Health to coordinate their departments’ activities to maximize the accessibility of work-related opportunities to Medicaid enrollees, with the Commissioner of Health noting that access to health care is the first step in supporting employment. For example, the governor indicated that the state would take steps to ensure that its existing vocational training workforce programs, including those under public benefit programs such as TANF and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), are available to Medicaid enrollees “at every opportunity, while increasing access to needed services that will keep them in the workforce.” She noted that work mandates without appropriate employment supports would likely “leave more Maine people uninsured without improving their participation in the workforce,” and that “Maine believes that providing appropriate educational opportunities and vocational training, along with critical health care, is the most effective way to lift people out of poverty and into the workforce.” 37 While emphasizing cross-agency collaboration and maximization of existing funding to support work, the state does not specify whether new resources will be available for such efforts.

In addition to state-led initiatives, Medicaid managed care plans can take steps to connect their members with job services and employment, as well as other support services. In a 2017 survey of Medicaid MCOs, 77% of MCOs reported that they had undertaken activities in the previous year to address enrollee needs in housing, 73% in nutrition and food security, and 51% in education. The survey further shows that 31% of MCOs reported efforts in the previous year to address their members’ employment needs directly, and 52% reported offering social services, such as WIC application assistance and employment counseling referrals, to their members in the previous year. The scope and depth of plan activities in these areas were not clear from the survey responses.

Some states require MCOs to assist their members with addressing barriers to work and finding employment. For example, West Virginia’s managed care contracts require MCOs to refer members who seek information about workforce opportunities to local workforce offices for additional assistance.38 For members that have behavioral health or medical needs that interfere with their ability to establish employment, the MCO is required to enroll the member in care management and establish a care plan to address those barriers to work. Massachusetts also requires its MCOs to develop care plans for their members that address identified social needs, including employment.39

CareSource, which operates a program called JobConnect in Georgia, Indiana, and Ohio, provides direct employment assistance to its members. JobConnect is part of a larger CareSource initiative called Life Services, which focuses on social determinants of health, particularly for low-income members. JobConnect is a voluntary program that offers members the chance to work one-on-one with life coaches to identify personal strengths and areas of social need. Interested members first enroll in JobConnect by completing a Health Risk Assessment, calling or emailing CareSource, or being referred by a community partner.40 Personal life coaches then assess participants’ resources, skills, interests, and needs, and they connect participants with community partners that provide social services to address members’ barriers to work, such as food banks, transportation vouchers, and other public benefit programs like SNAP and TANF. JobConnect life coaches also link participants with employment opportunities by working directly with employers and connecting members with work support resources such as free computer classes. CareSource directly funds several other employment-related supports, including fee contributions for High School Equivalency exams and transportation to test preparation classes.41 In addition, CareSource offers such JobConnect services to non-member parents whose children are enrolled in CareSource.42 JobConnect has served 2,870 members since its 2015 inception and is 90% funded by CareSource and 10% from external grants. Outcomes for Life Services more broadly show 5,016 total community referrals, and 86% of members retaining employment.43 CareSource offers multiple lines of business, so the degree to which Life Services and JobConnect serve Medicaid enrollees specifically is unclear.

Across state and MCO voluntary employment support programs, several themes emerge. First, due to their voluntary nature, they all allow Medicaid enrollees to keep their coverage. The programs often take a targeted approach to the county, locality, or individuals that they serve, including a focus on identifying the specific barriers that may prevent a particular individual from working and providing services to address those barriers and support enrollees’ ability to work. These programs also often incorporate coordination among state agencies or public benefit programs, such as TANF and SNAP, as well as community-based organizations that can help meet enrollees’ needs. Finally, the most robust programs include high-touch referrals to these partners as well as follow-up to track enrollee progress.

State Medicaid agency and MCO employment initiatives customize their programs to the county or locality that they serve. For example, Louisiana’s program is designed to operate in a specific local context, with the express goal of replicability by and customization to other locales. Eligible participants are a subset of those in the Medicaid expansion population who reside in the state’s Oachita Parish and whom LDCC identifies as standing to benefit from work training. Similarly, CareSource’s JobConnect program draws its life coaches from the communities that they serve, allowing for greater connection with local resources and opportunities.

Voluntary employment support programs emphasize the importance of identifying individuals who are not working but currently are in a position to work, and then assessing and addressing their barriers to employment. For example, in Montana, the HELP-Link program begins with a formal assessment of participants’ personal barriers and challenges to employment or higher earnings. Job Service staff then analyze these assessments and connect the enrollees to personalized services that will address the barriers that they have identified. Such services can include childcare referrals for parents, help with resumes, or job training. MTDLI has conducted HELP-Link outreach with limited funds and focused resources on those who completed the survey or indicated interest in the program. This targeted outreach resulted in higher take-up for HELP-Link than other MTDLI programs. Similarly, Louisiana’s pilot program with LDCC includes an intake process that involves completion of a participant assessment tool and an individual participant plan.44 The assessment tool includes a participant’s work experience, skills, challenges, and interests, while the plan then establishes the support services and educational activities identified for that participant.

Voluntary employment support programs for Medicaid enrollees often involve coordination with other state agencies and programs, as well as community-based organizations, to connect enrollees with targeted services. For example, both Montana’s and Maine’s Medicaid agencies partner with their TANF and SNAP programs to connect Medicaid enrollees with work supports available through those programs. Both HELP-Link and JobConnect link participants with community-based organizations, such as local non-profit partners, that can assist them with needs such as financial counseling, food security, or internet service. Louisiana’s pilot program involves cross-agency collaboration, as the state’s Department of Health partners directly with LDCC to run the initiative.

HELP-Link and JobConnect also demonstrate the importance of high-touch referrals and follow-up to the success of their employment programs. After development of the individualized employment plan, state workforce consultants regularly follow up to help participants achieve the goals outlined in their plans. They employ a team approach designed to coach clients through a variety of applications and paperwork for training programs. If a participant’s barriers to work fall under the mission of another state agency or community-based organization, HELP-Link staff will refer that participant to the appropriate partner. After employers for specific jobs, the most common referrals are to the state’s workforce programs, as well as its Office of Public Assistance for help with housing, childcare, food stamps, or TANF.45 HELP-Link staff then work with those partner organizations to provide participants with comprehensive case management. Similarly, CareSource’s JobConnect life coaches work closely with participants throughout every step of the program, from initial screenings to post-employment check-ins, to ensure that members are receiving services that address their barriers to employment and then allow them to advance in new jobs.

Across initiatives, state resources may not be adequate to provide the full level of support required to address low-income Medicaid enrollees’ barriers to work. For example, while Montana operates HELP-Link with specifically allocated state funds, the state has acknowledged the insufficiency of those resources to meet demand for the program. As a result, the state has so far targeted resources to a subset of the HELP-Link-eligible population to make most efficient use of available funding, noting that other Montana Medicaid enrollees may face barriers that hinder their participation in the program. Under the 2019 legislation that extended HELP-Link, the state is exploring changes to the program to increase its cost-effectiveness and expand participation. In Louisiana and Maine, the governors have developed new programs or emphasized existing ones that can help address Medicaid enrollees’ barriers to work, but the states have not indicated whether additional staff or funding is available to support these initiatives. Finally, while CareSource is covering 90% of the cost of JobConnect operations, it is unclear whether most managed care plans have sufficient resources to do so, and how managed care plans can fund such initiatives more generally. Such questions about adequate resources pertain to both maintaining existing program operations and expanding the programs to more eligible participants who could benefit from them.

Looking ahead, it will be important to evaluate the effects of the small number of existing voluntary work support programs on enrollee participation and employment rates and to identify common elements of success and key challenges as well as costs needed to administer a successful program. Montana has published state data and reports46 on outcomes through SFY 2019, and there may be an opportunity to compare that experience with a work requirement (including any increase in work, as well as coverage losses due to noncompliance), if it is ultimately implemented in the state. The state’s legislation scheduled the Medicaid work requirement to take effect beginning January 1, 2020, contingent on CMS approval of the Section 1115 waiver that the state submitted in August 2019. However, the state announced in November 2019 that it would not be able to follow that schedule given that it is still awaiting federal approval of its waiver.47 In addition, although Louisiana had planned to release early results from the LDCC pilot program, which is scheduled to run through the end of December 2019, the state has yet to publish implementation documents or initial program findings. MCOs with work support programs like JobConnect can share best practices and collect data to build their evidence base, with a particular focus on Medicaid enrollee participation and outcomes. Evaluation of these and other work support initiatives can help other states, communities, and plans develop similar models.

Voluntary work support programs offer an opportunity to address enrollee employment needs, but funding presents a challenge. State efforts to invest in voluntary work support programs may be able to increase employment rates among Medicaid expansion enrollees without conditioning eligibility on employment. CMS indicated that it cannot make federal Medicaid matching funds available for such programs, so successful models must find other resources to address Medicaid enrollees’ barriers to work. MCOs can explore opportunities to use “value-added” services or other funding mechanisms to address enrollee social determinants of health. As Medicaid work requirements continue to face litigation, and research shows limited gains in employment from such requirements, voluntary programs that support work and can be implemented without waiver authority can provide another option for states interested in supporting work for enrollees who qualify through non-disability pathways. However, their success may be limited without an infusion of new resources.

Medicaid provides health coverage and long-term care services and supports for low-income individuals and families, covering more than 76 million Americans and accounting for about 1 in 6 dollars spent on health care.1 Medicaid is a large source of spending in both state and federal budgets, making program integrity efforts important to prevent waste, fraud, and abuse and ensure appropriate use of taxpayer dollars. Recent audits and improper payment reports have brought program integrity issues back to the forefront. This brief explains what program integrity is, recent efforts at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to address program integrity, and current and emerging issues. It finds:

Program integrity refers to the proper management and function of the Medicaid program to ensure it is providing quality and efficient care while using funds–taxpayer dollars–appropriately, with minimal waste. Improper payments, which are often cited when discussing program integrity, are not necessarily the same as criminal activities like fraud and abuse, which are a subset of improper payments. The federal government and states share the responsibility of promoting program integrity. CMS conducts a range of actions focused on program integrity. Outside of CMS, other federal agencies, including the Office of Inspector General (OIG) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO), undertake program integrity and oversight efforts.

Recent CMS actions to promote program integrity have focused on federal audit and oversight functions. CMS released a program integrity strategy in June 2018 and a notice in June 2019 highlighting program integrity as a priority and emphasizing new and planned actions centered on stronger audit and oversight functions, increased beneficiary eligibility oversight, and enhanced enforcement of state compliance with federal rules

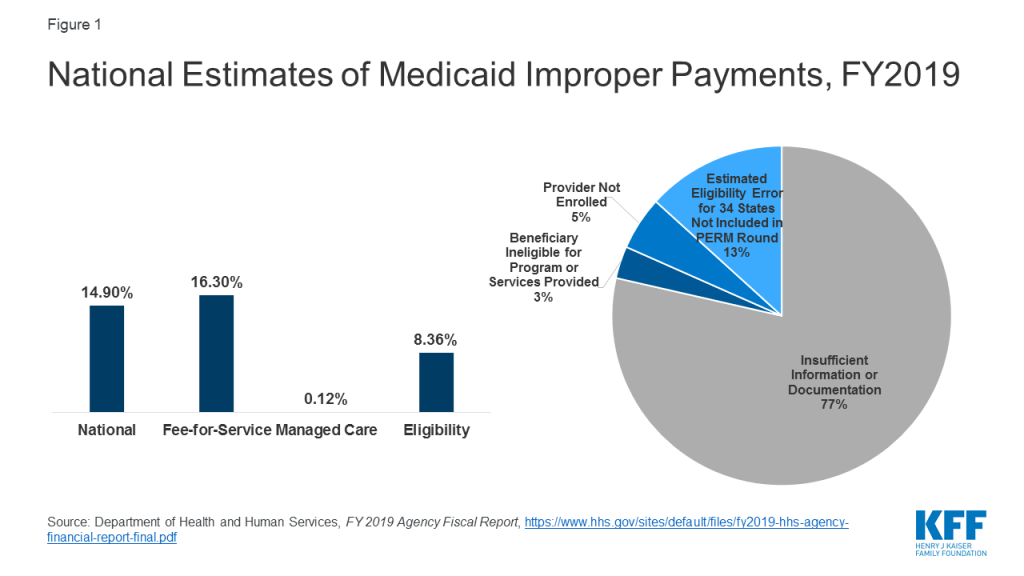

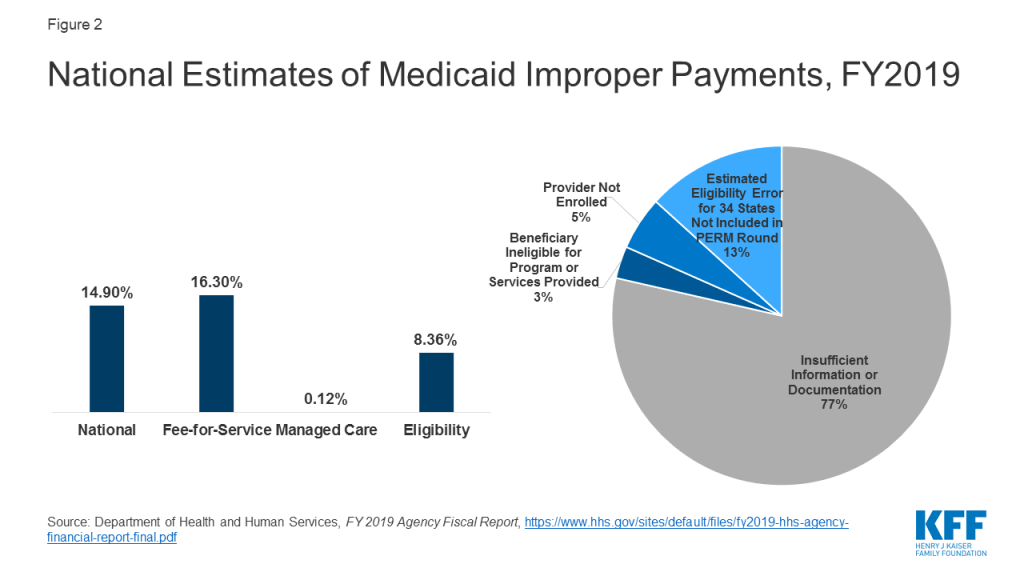

CMS released Payment Error Rate Measurement (PERM) estimates for Medicaid that include eligibility determinations for the first time since implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The PERM estimate is based on reviews of fee-for-service and managed care claims and eligibility determinations. The eligibility component was suspended for several years as states implemented the ACA and was reintegrated into the 2019 rate. The national Medicaid improper payment rate for 2019 is 14.90% or $57.36 billion.2 A separate HHS report shows a 16.3% error rate for fee-for-service claims, an 8.36% error rate for eligibility, and a 0.12% error rate for the managed care claims (Figure 1). HHS reports that 77% of improper payments were due to missing information and/or states not following the appropriate process for enrolling providers and/or determining beneficiary eligibility. These payments do not necessarily represent payments for ineligible providers or beneficiaries, since they may have been payable if the missing information had been on the claim and/or the state had complied with requirements. It finds 8% of improper payments were for ineligible providers or beneficiaries.

CMS’s heightened focus on reducing errors in eligibility determinations could have trade-offs that make it more difficult for eligible people to obtain and maintain coverage. CMS plans to change eligibility rules to tighten standards for eligibility verification.3 While such changes could reduce instances of ineligible people being enrolled in the program and other eligibility errors, they also could also result in greater enrollment barriers for people who are eligible for the program at the same time. PERM error rates do not capture errors associated with eligible people being disenrolled or denied enrollment.

Focusing program integrity efforts on areas identified as contributing to larger amounts of improper payments could yield greater returns on program integrity efforts. HHS indicates that Medicaid improper payment rates have been driven by errors associated with screening and enrollment of providers.4 Moreover, PERM only represents one tool to measure improper payments and does not fully capture all losses associated with program waste, fraud, and abuse.

Through administrative actions related to program integrity, CMS is making changes that could have broader implications for eligibility and spending. As noted, CMS guidance and planned changes to eligibility rules to tighten standards for verification could restrict enrollment in the program. Further, through guidance and regulation, CMS has heightened oversight of state claiming for the ACA expansion, increased oversight of and made changes to state claiming for federal funds under Section 1115 waivers, and proposed changes to supplemental payments. These changes could reduce federal spending on the program and limit states ability to access federal matching funds. In some cases, reduced federal spending may be tied to additional oversight to ensure states are complying with current rules, while in other cases the reductions may reflect CMS changes or proposed changes in policies.

Program integrity refers to the proper management and function of the Medicaid program to ensure it is providing quality and efficient care while using funds–taxpayer dollars–appropriately with minimal waste. Program integrity efforts work to prevent and detect waste, fraud, and abuse, to increase program transparency and accountability, and to recover improperly used funds. The goal of program integrity initiatives is to help ensure that: eligibility decisions are made correctly; prospective and enrolled providers meet federal and state participation requirements; services provided to enrollees are medically necessary and appropriate; and provider payments are made in the correct amount and for appropriate services.5

There are an array of challenges associated with implementation of an effective and efficient Medicaid program integrity strategy. Some challenges cited by MACPAC include: overlap between federal and state responsibilities; lack of collaboration and information sharing among federal agencies and states; lack of information on the effectiveness of program integrity initiatives and appropriate performance measures; lower federal matching rates for state activities not directly related to fraud control; incomplete and outdated data; and few program integrity resources.

Improper payments are often cited when discussing program integrity, but they are not the same as fraud and abuse. The GAO reports improper payments across all government programs, including Medicaid. There are also other audits specific to Medicaid that measure errors and improper payments. These improper payment and error measures are often cited when discussing program integrity. However, improper payments may result from a variety of circumstances including errors, waste, abuse, and fraud. Errors and waste may result in unnecessary expenditures or improper payments, but are not criminal activities like fraud and abuse (see Box 1 for definitions).

Box 1: Definition of Terms

Improper Payment: Any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount (including overpayments and underpayments) under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other requirements. It includes any payment to an ineligible recipient, any payment for an ineligible good or service, any duplicate payment, any payment for a good or service not received, and any payment that does not account for credit for applicable discounts. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance instructs agencies to report as improper payments any payments for which insufficient or no documentation was found.

Error: The inadvertent product of mistakes and confusion.

Waste: Inappropriate utilization of services and misuse of resources.

Abuse: Action that is inconsistent with acceptable business and medical practices

Fraud: The intentional act of deception and misrepresentation.

One of CMS’s primary enforcement mechanisms to support program integrity is disallowance. CMS has the ability to work with states regarding the repayment of the federal share of improper payments. When an improper payment is identified, states can voluntarily return federal funds or CMS can issue a disallowance. CMS has been working through backlogs of potential disallowances. However, corrective action plans, rather than disallowances, are the typical enforcement mechanism for dealing with error rates found through the PERM process.

Ensuring program integrity in Medicaid is the responsibility of both the federal government and the states. State Medicaid agencies manage the day-to-day operations of Medicaid (conducting enrollment and eligibility verification; licensing and enrolling providers; setting rates and paying providers; monitoring quality of care and provider claims (“data-mining”); conducting audits; detecting improper payments and recovering overpayments; and investigating and prosecuting provider fraud and patient abuse or neglect).6 In addition, states are required to have a Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) that is separate from the Medicaid agency to conduct criminal investigations and prosecutions related to fraud. The federal government oversees and helps finance state program integrity efforts and monitors and enforces state compliance with federal rules; reviews state agency performance; audits, evaluates, and investigates individuals or organizations suspected of fraud; imposes sanctions; and provides training and guidance to the states.7 For more information on responsibilities of each agency, see Appendix A.

Since the enactment of Medicaid in 1965, the statute has evolved to promote program integrity. Key recent program integrity legislative milestones include the following:

The focus of program integrity efforts have also evolved at CMS in response to changing legislation, policy developments and priorities. Program integrity efforts historically focused on the recovery of misspent funds, but initiatives included in the ACA attempted to move beyond “pay and chase” models to focus more heavily on prevention and early detection of fraud and abuse and other improper payments.

Recent actions by CMS to promote program integrity have focused on federal audit and oversight functions. CMS released a program integrity strategy in June 2018 and a notice in June 2019 highlighting program integrity as a priority and emphasizing new and planned actions centered on stronger audit and oversight functions, increased beneficiary eligibility oversight, and enhanced enforcement of state compliance with federal rules. Specifically, CMS points to initiatives focused on audits of state claiming for federal match and rate setting, including high-risk vulnerabilities identified by the GAO and OIG, which include improper payment rates, state use of supplemental payments, and oversight of waiver demonstration programs.13 It also indicates that it will conduct new audits of state beneficiary eligibility determinations with a focus on the impact of changes to state eligibility policy as a result of the ACA Medicaid expansion. Below are a range of recent CMS program integrity efforts and initiatives, including those highlighted in its recent guidance. This is not necessarily a comprehensive list of all current CMS program integrity strategies, but highlights recent areas of focus and new or planned future actions. Moreover, the list does not capture the full range of program integrity efforts of states and other federal agencies. Outside of CMS, other federal agencies, including the OIG and GAO, also are engaged in program integrity and oversight efforts.

The PERM program measures improper payments in Medicaid and CHIP and produces error rates for each program.14 The error rates are based on reviews of the fee-for-service and managed care claims and eligibility determinations in the fiscal year under review. The error rate is not a “fraud rate” but a measurement of payments made that did not meet statutory, regulatory or administrative requirements. Each state is audited on a rolling three year basis and annually produces national and state-specific improper payments. In light of the major changes to the way states determine eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP under the ACA, the eligibility determinations component of PERM was temporarily suspended between 2015 and 2018.

In November 2019, CMS released the first PERM estimates with eligibility determinations reintegrated into the review since implementation of the ACA. Estimated improper payments for Medicaid were 14.9% or $57.36 billion in 2019 across all three components included in the PERM review (fee-for-service, managed care, and eligibility).15 Given the reintegration of the eligibility component, the overall rates and payments are not comparable with prior years.16 In a separate report, HHS released estimates for each component in PERM, showing a 16.30% rate for fee-for-service, 0.12% rate for managed care, and 8.36% rate for eligibility.17 These data show that the fee-for-service component accounted for the highest improper payment rate (Figure 2). GAO has reported that the managed care component does not fully account for all program risks in managed care, and points to overpayments and unallowable costs that have not been accounted for by previous estimates.18

HHS reports that the majority of improper payments do not necessarily represent expenses that should not have occurred. HHS identified a range of factors contributing to improper payments, including the reintegration of the eligibility component, improper payments due to insufficient documentation, and noncompliance with screening and enrollment of providers.19 HHS finds that over three-quarters (77%) of Medicaid improper payments were due to instances where information was missing and/or states did not follow the appropriate process for enrolling providers and/or determining beneficiary eligibility, which do not necessarily represent payments for ineligible providers or beneficiaries.20 HHS notes that if the missing information had been on the claim and/or had the state complied with the enrollment or redetermination requirements, then the claims may have been payable. It finds that 8% of improper payments were for ineligible providers or beneficiaries.

In June 2019 guidance, CMS reminded states about program integrity obligations particularly related to expenditures claimed at the enhanced match for the ACA Medicaid expansion group. The guidance details a program readiness checklist to ensure accurate eligibility determinations and claiming at the appropriate match rate. The guidance encouraged states to use periodic data matching to identify beneficiaries who may have had a change in circumstance that affects their eligibility. The guidance also indicated that state program integrity reviews, PERM, Medicaid Eligibility Quality Control (MEQC) and other audit findings will be part of oversight activities. Additionally, CMS noted plans to propose regulations to make changes to eligibility rules to increase requirements around verification, monitoring of changes in beneficiary circumstances, and eligibility redeterminations.

As noted, PERM measures eligibility determinations as one component of improper payments in Medicaid. As described above, CMS resumed the eligibility component of PERM reviews in 2019. For the eligibility component, a federal contractor assesses states’ application of federal rules and the state’s documented policies and procedures related to beneficiary eligibility. Examples of noncompliance with eligibility requirements include a state: enrolling a beneficiary when he or she is ineligible for Medicaid; determining a beneficiary to be eligible for the incorrect eligibility category, resulting in an ineligible service being provided; not conducting a timely beneficiary redetermination; or not performing or completing a required element of the eligibility determination process, such as income verification.21 While PERM payment errors may capture over and underpayments and errors in eligibility determinations, they do not capture errors associated with eligible people being disenrolled or denied enrollment.

The MEQC program uses state directed reviews in the two off-cycle PERM years to conduct eligibility reviews. Under the MEQC program, states design and conduct projects, known as pilots, to evaluate the processes that determine an individual’s eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP. States have great flexibility in designing pilots to identify vulnerable or error-prone areas. The MEQC program does not generate an error rate.

Based on audits from the OIG, CMS is conducting eligibility audits in select states. As a result of OIG findings tied to eligibility, CMS is conducting additional audits in California, New York, Kentucky, and Louisiana.22 These audits will be in addition to PERM and MEQC reviews.

CMS has issued guidance related to oversight of federal matching funds provided to states through Section 1115 waivers. Specifically, in guidance, CMS has noted oversight concerns related to states obtaining federal Medicaid matching funds under waivers for Designated State Health Programs that previously were fully state-funded and described several actions it is taking to increase documentation and review of claiming of federal funds for these programs. CMS also noted that it will no longer accept state proposals for new or renewing Section 1115 demonstrations that rely on federal matching funds for these programs. In separate guidance, CMS outlined recent changes to its approach to calculating budget neutrality for Section 1115 waiver extensions that are intended to strengthen fiscal accountability and prevent the federal government’s exposure to excessive expenditures.

In November 2019, CMS proposed regulations to make changes to supplemental payments that it indicates are designed to promote program integrity and increase transparency. The proposed rule would establish new reporting requirements for states to provide CMS with certain information on supplemental payments to Medicaid providers and applicable upper payment limits. The proposed rule also places new limits on supplemental payments (up to 150% of fee-for-service base rates or 175% of base rates in rural areas) and adds new requirements for states to use financing mechanisms such as intergovernmental transfers (IGTs), certified public expenditures (CPEs), and provider taxes and donations.

CMS plans to conduct additional audits of high-risk areas. CMS has indicated plans to conduct additional audits of state claiming of federal matching dollars to address areas that have been identified as high-risk by GAO and OIG, as well as other behavior previously found detrimental to the Medicaid program.23

Beginning in 2014, CMS implemented enhanced review of state capitation rates for coverage of the new expansion population.24 CMS has since expanded that review to all managed care capitation rates and adopted a regulation providing more detailed requirements related to rate setting. All managed care rates are reviewed to ensure that the rates are actuarially sound and in compliance with Medical Loss Ratios (MLRs).25 CMS has indicated plans to release additional guidance on the Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule from 2016 to further state implementation and compliance with program integrity safeguards, such as reporting overpayments and possible fraud.26 In November 2019, CMS published an informational bulletin outlining changes to the Medicaid managed care contract approval process and future steps to streamline the process.

Provider screening and enrollment is required for all providers in Medicaid fee-for-service or managed care networks. Additionally, the ACA requires states to terminate provider participation in Medicaid if the provider was terminated under Medicare or another state program, such as CHIP. CMS has multiple tools to assist states with provider screenings and enrollment compliance, including leveraging Medicare data. CMS pointed to additional provider screening efforts in its 2018 program integrity strategic plan and noted that it has released guidance regarding Medicaid provider screening and enrollment for Medicaid managed care organization network providers.27 It also referenced plans to implement a pilot to screen Medicaid providers on behalf of states. CMS indicates that these actions are designed to improve efficiency and coordination across Medicare and Medicaid, reduce state and provider burden, and address one of the biggest sources of error included in the PERM rates.

CMS is engaged in several efforts to increase access to data as part of program integrity and transparency efforts. CMS is developing enhanced administrative data through T-MSIS, which will provide increased eligibility, utilization and claims data that will be used broadly to monitor enrollment, payment, access, quality, and program integrity efforts.28 CMS has released a Medicaid Scorecard that presents selected state performance measures related to their Medicaid programs. The CMS Medicaid program integrity strategy also highlights data analytic pilots and efforts to increase data sharing with states.

Conducting outreach and education for states and providers is an additional component of program integrity efforts. The Medicaid Integrity Institute (MII) provides training and education to state Medicaid program integrity staff annually. CMS also has initiatives to collaborate with states and other entities to share best practices and conducts State Program Integrity Reviews to assess the effectiveness of states’ program integrity efforts. CMS has indicated plans for provider education efforts that will focus on providers who have high error rates and educate them on billing requirements as well as educating providers through Comparative Billing Reports, which show providers how their billing patterns compare to their peers.29

Through administrative actions related to program integrity, CMS is making policy changes that could have broader implications for eligibility and spending, particularly related to the ACA Medicaid expansion. Through guidance and regulation, CMS recently heightened the focus on federal oversight of state claiming for the ACA expansion, increased oversight of and made changes to state claiming for federal funds and budget neutrality for Section 1115 waivers, and proposed changes to supplemental payments and other financing mechanisms. CMS has also issued guidance to states on eligibility practices and indicated plans to issue regulations to make changes to eligibility rules to tighten standards for verification. While CMS has taken these actions as part of its goals to increase program integrity and transparency, these changes could have broader implications for eligibility and spending. For example, the changes to eligibility practices and rules could restrict enrollment in the program and the changes to state claiming for federal funds and budget neutrality rules for Section 1115 waivers and some of the proposed changes to supplemental payments and other financing mechanisms could reduce federal spending on the program and limit states ability to access federal matching funds. In some cases, reduced federal spending may be tied to additional oversight to ensure states are complying with current rules, while in other cases the reductions may be tied to CMS changes or proposed changes in policies.

CMS’s heightened focus on reducing errors in eligibility determinations could have trade-offs that make it more difficult for eligible people to obtain and maintain Medicaid coverage. CMS has increased its focus on beneficiary eligibility determinations as part of program integrity efforts, and indicated that it plans to take steps to change eligibility rules and tighten standards for eligibility verification to reduce improper payment rates associated with eligibility errors.30 As noted, these errors do not necessarily reflect fraud and abuse or that the individual was not eligible for the program. Increased documentation and verification requirements could reduce instances of ineligible people being enrolled in the program and other eligibility errors, but also could result in greater enrollment barriers for people who are eligible for the program at the same time. Recent experiences in some states suggest that eligible individuals may be losing coverage due to increased periodic verification checks or because they failed to receive notices and/or did not provide documentation within required timeframes. While PERM error rates can measure under and over payments, they do not capture errors associated with eligible people being disenrolled or denied enrollment. States can adopt policies to streamline and simplify eligibility, which can reduce error rates and promote stable enrollment. For example, 24 states have adopted 12-month continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid, meaning they remain eligible for the 12-month period, even if they have small changes in income that increase above the eligibility limit. This policy helps reduce churn or people moving on and off the program due to small and/or temporary changes income, for example, due to seasonal work or overtime, as well as potential errors associated with fluctuating incomes.

Focusing program integrity efforts on areas identified as contributing to larger amounts of improper payments could yield greater returns on program integrity efforts. Improper payments are being largely driven by errors associated with screening and enrolling providers rather than beneficiary eligibility. In its program integrity strategy, CMS notes that its efforts to assist states with provider screening are designed to address one of the biggest sources of error measured by PERM.31 As noted, the HHS report shows that the fee-for-service component of PERM accounted for the highest improper payment rate.32 HHS further indicates that, since FY2014, Medicaid improper payment rates have been driven by errors associated with screening and enrollment of providers.33 Moreover, PERM only represents one tool to measure improper payments and may not fully capture all losses associated with program waste, fraud, and abuse. For example, GAO has reported that the managed care component of PERM does not fully account for all program risks in managed care and points to overpayments and unallowable costs that previously have not been accounted for by the estimate.34 Other reports point to losses specific to provider fraud.35 There may also be other program areas that are not currently a focus of program integrity efforts that are contributing to waste in the program. For example, the GAO recently found weaknesses in CMS’s oversight of the administrative costs of Section 1115 waiver demonstrations with work requirements, noting that CMS did not consider administrative costs during approval and that current procedures may be insufficient to ensure costs are allowable and matched at the correct rate, especially for administrative costs.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) – Works to deter, detect, and combat fraud and abuse and take action against those that commit or participate in fraudulent activities. These activities are primarily implemented through the Center for Program Integrity (CPI), which was created to coordinate all program integrity efforts across CMS and other state and federal partners.

Department of Justice (DOJ) – Monitors and enforces federal fraud and abuse laws and prosecutes law violators. Several offices within DOJ are involved in Medicaid program integrity activities, including of the U.S. Attorneys, the Criminal Division, and the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI).36

Office of Inspector General (OIG) of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) – Conducts audits, investigations, and evaluations of HHS programs, including Medicaid. It oversees state Medicaid Fraud Control Units (MFCUs), provides resources and education to the health care industry and the public to combat fraud and abuse.37

Government Accountability Office (GAO) – Is a Congressional agency that investigates the federal spending of tax dollars and individual fraud allegations. GAO can audit agency operations and assess whether programs and policies are meeting objectives.38 Other Congressional agencies involved in program integrity activities include the Congressional Oversight Committee, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), and the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Advisory Commission (MACPAC).

State Medicaid Agency – Develops policies and handles the day-to-day operation of Medicaid. In some states, program integrity responsibilities are distributed across agencies, including the Office of the Attorney General and the Office of the State Auditor.39 Most program integrity efforts implemented by the states are matched at the standard 50 percent administrative match rate, but some efforts receive higher match rates, including the Medicaid Management Information Systems and survey and certification.

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) – Is an entity of state government that investigates program administration and health care providers, prosecutes (or refers) those defrauding the program, and collects overpayments. They also review cases of abuse and neglect and the misuse of patient personal funds in long-term care facilities.40 MFCU costs are matched at a 75 percent rate.

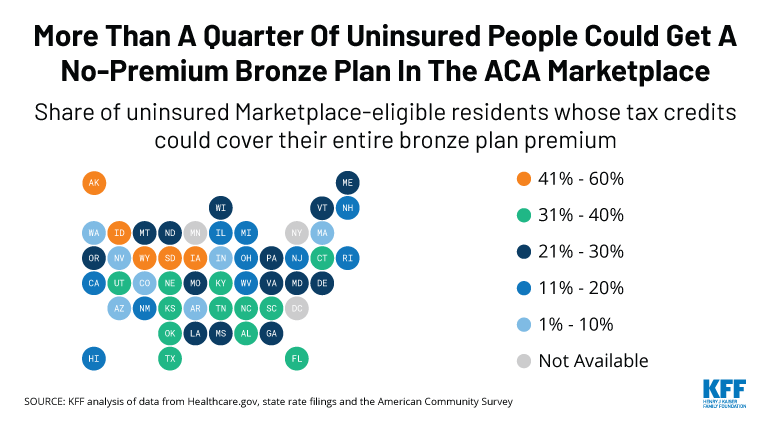

As the Affordable Care Act’s open enrollment period nears an end in most areas this week, a new KFF analysis finds that 4.7 million currently uninsured people could get a bronze-level plan for 2020 and pay nothing in premiums after factoring in tax credits, though the deductibles would be high.

That works out to 28 percent of the 16.7 million uninsured individuals who are potential customers for coverage through ACA marketplaces.

Half of the uninsured who could get a free bronze plan live in one of four large states: Texas (1,151,300 people), Florida (694,800), North Carolina (338,200) and Georgia (303,600). The analysis has detailed data on the number and share of the uninsured in each state who have access to a free bronze plan.

Iowa by far has the largest share (59%) of potential marketplace customers who could enroll in a bronze plan without having to pay a premium. This reflects a combination of factors, including the state’s relatively high premiums for its benchmark silver plan that results in larger tax credits for low- and moderate-income residents.

Other states with large shares of uninsured residents who could sign up for a no-premium bronze plan include Alaska (45%), Wyoming (44%), Idaho (41%), South Dakota (41%), North Carolina (40%), Oklahoma (40%) and South Carolina (40%).

A bronze plan could provide the uninsured with access to some primary care, no-cost preventive services, and financial protection against high health costs, though they come with very high annual deductibles ($6,506 on average in 2020).

Consumers may want to consider paying a premium for a silver plan instead so that they can benefit from cost-sharing subsidies available under the ACA. The ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies are available to people with incomes below 250% of the federal poverty level who sign up for a silver plan, resulting in deductibles ranging from $209 to $3,268 depending on income level.

In most states, potential customers have until Sunday, Dec. 15, to sign up for a marketplace plan, though a few states that run their own marketplaces have extended open enrollment periods. KFF’s Health Insurance Marketplace Calculator allows users to enter their income, age, and family size and get estimates of premiums and available subsidies for insurance purchased on the ACA exchanges. In addition, KFF has updated its searchable online collection of 300 frequently asked questions about the health insurance marketplace, tax credits and other open-enrollment consumer issues.

While the percent of the population without health coverage has decreased since the major coverage expansion in the ACA, at least 10% of the non-elderly population is still uninsured. This analysis looks at how many of the remaining uninsured are eligible for premium subsidies large enough to cover the entire cost of a bronze plan, which is the minimum level of coverage available on the Marketplaces.

The premium tax credits that subsidize Marketplace coverage are calculated using the second-lowest cost silver plan in each rating area as a benchmark. As was the case in 2019, many unsubsidized silver plans continue to be priced relatively high because insurers generally loaded the cost from the termination of federal cost-sharing reduction payments entirely onto the silver tier (a practice sometimes called “silver loading”). The relatively higher price for silver plans means subsidy-eligible Marketplace enrollees will continue to receive large premium tax credits in 2020. These subsidies – which can be used towards the premium of any Marketplace plan – also continue to make lower premium bronze plans more likely to be available for $0 than before cost-sharing reduction payments were terminated.

In this analysis, we focus specifically on the approximately 16.7 million uninsured people who could be shopping on the Marketplace, regardless of whether or not they are eligible for a subsidy.1 We therefore exclude people who are eligible for Medicaid, those over the age of 65, and those who are undocumented immigrants (who are not permitted to buy Marketplace coverage).

We estimate that 28% of uninsured individuals who could shop on the Marketplace, or 4.7 million people nationwide, are eligible to purchase a bronze plan with $0 premiums after subsidies in 2020. This figure is similar to 2019, when 27% of uninsured individuals, or 4.2 million people, could purchase a no-premium bronze plan.

As shown on the map and table below, the availability of free bronze plans varies widely between states. More than half of the uninsured who could get a free bronze plan live in Texas, Florida, North Carolina, or Georgia. Other states with large shares of uninsured residents who could sign up for a no-premium bronze plan include Iowa (59%), Alaska (45%), Wyoming (44%), Idaho (41%), and South Dakota (41%).

Rather than continuing to go without insurance, the 4.7 million uninsured people eligible for no-premium bronze plans would benefit from the financial protection health insurance offers. While bronze plans have high deductibles, they all cover preventive care with no out-of-pocket costs, and a number of bronze plans cover additional services, such as a few physician visits, before the deductible. If a low-income enrollee in a bronze plan needs a hospitalization, they will likely have difficulty affording the deductible, but the deductible will also likely be much less than the cost of a hospitalization without insurance.