What Issues Will Uninsured People Face with Testing and Treatment for COVID-19?

With COVID-19 cases rising in the US, issues surrounding access to testing and treatment for uninsured individuals have taken on heightened importance. Efforts to limit the spread of the coronavirus in the United States are dependent on people who may have been exposed to the virus or who are sick getting tested and seeking medical treatment. However, the uninsured are likely to face significant barriers to testing for COVID-19 and any care they may need should they contract the virus.

In 2018, there were nearly 28 million nonelderly people in the US who lacked health insurance. States that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA generally have higher uninsured rates than states that did. Adults, low-income individuals and people of color are at greater risk of being uninsured. Most uninsured lack coverage because of high cost or because of a recent change in their situation that led to a loss of coverage, such as a loss of a job. Though most uninsured people have a full time worker (72%) or part-time worker (11%) in their family, many people do not have access to coverage through a job, and some people, particularly poor adults in states that did not expand Medicaid, remain ineligible for financial assistance for coverage.

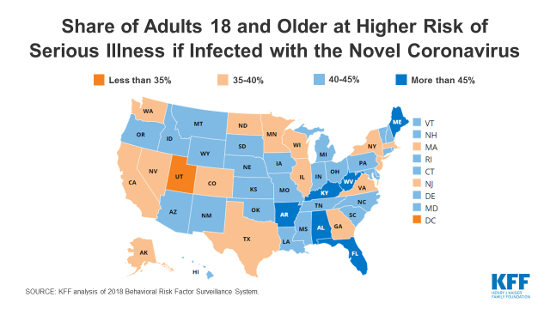

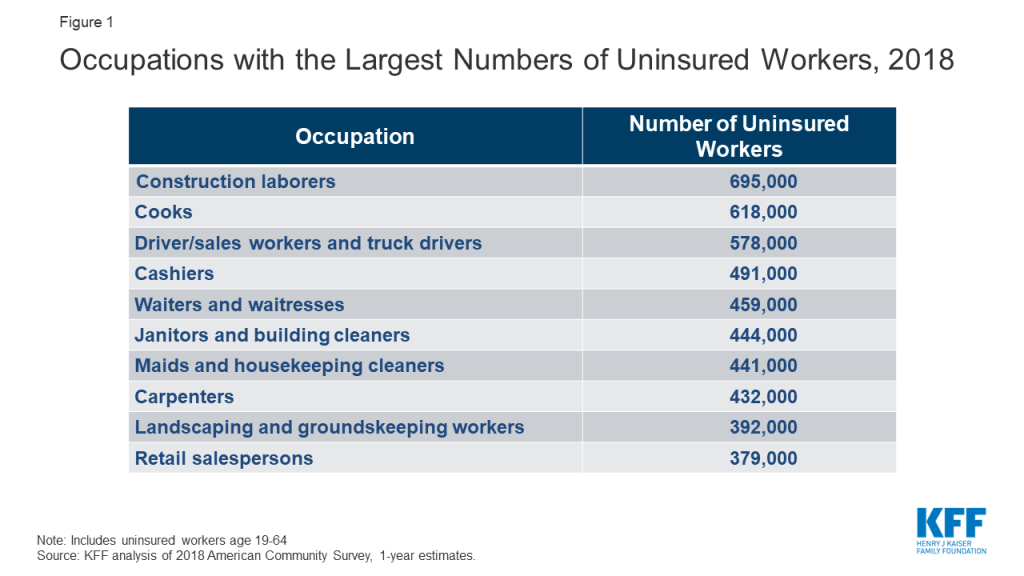

Many uninsured adults work in jobs that may increase their risk of exposure to COVID-19. Most uninsured adults are working. Because of the jobs they have, uninsured workers may be at greater risk of exposure to the disease. Among the top ten occupations reported by the uninsured, many are service-oriented, such as drivers, cashiers, restaurant servers and cooks, and retail sales that cannot be performed through telework and bring the uninsured into regular contact with the public (Figure 1). In addition, data analysis finds that nearly six million adults who are at higher risk of getting a serious illness if they become infected with coronavirus are uninsured.

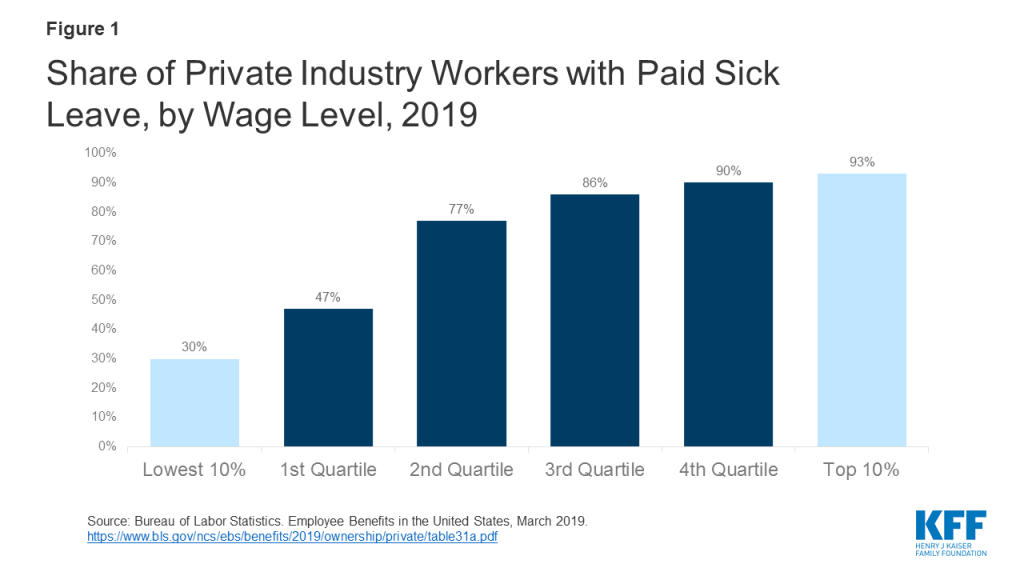

Uninsured workers who must take off work because they or family members are sick could face significant financial consequences. The U.S. does not have a federal law guaranteeing paid sick leave, and only 11 states and DC currently require paid sick leave. The burden of the lack of paid sick leave falls more heavily on low-wage and uninsured workers. In 2018, just over a quarter (26%) of uninsured workers said they had paid sick leave. Facing the risk of not getting paid or possibly losing their position if they do not show up for work, uninsured workers who are not provided sick leave may be reluctant to take time off, which could put their health at risk and could undermine efforts to control the spread of coronavirus.

Congress enacted legislation that would require certain employers to provide paid sick leave during this public health crisis; however, this new policy will not reach all uninsured workers. Under the emergency paid sick leave provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, workers in all public agencies as well as at some private firms with between 50 and 500 employees must be compensated at least a portion of their regular pay for 14 days if they take time off to address health needs for themselves or family members or to care for children due to school closures. If workers need more than 14 days off work to care for children due to school closures, they may be able to obtain up to 2/3 of their typical compensation for up to three months, but this policy does not extend to all workers and excludes employees at businesses with more than 500 employees. These new leave policies take effect two weeks after enactment of the legislation and the benefits are not retroactive, which means that uninsured workers who already took leave due to coronavirus would not be compensated for that time.

Barriers to COVID-19 Testing and Treatment

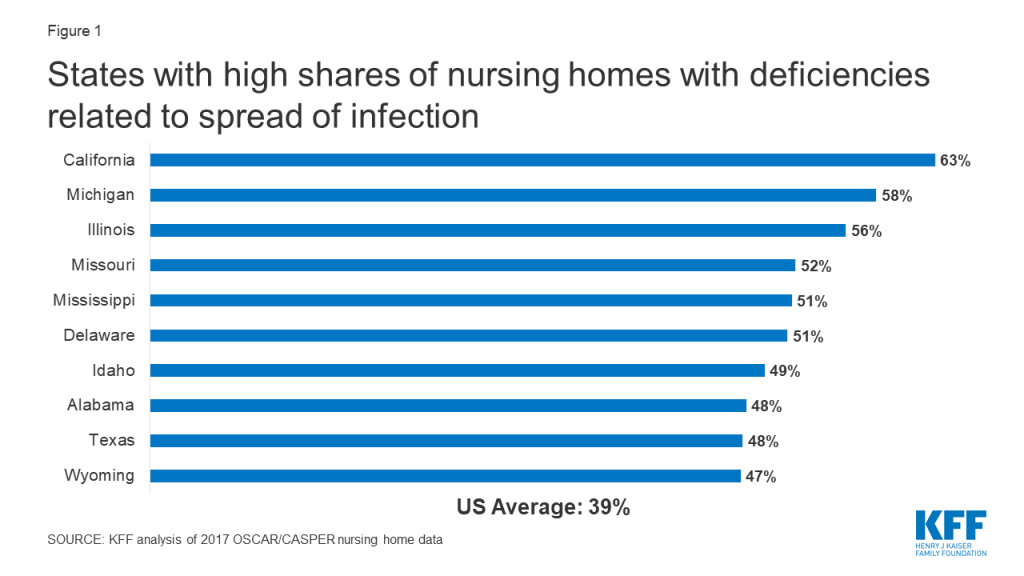

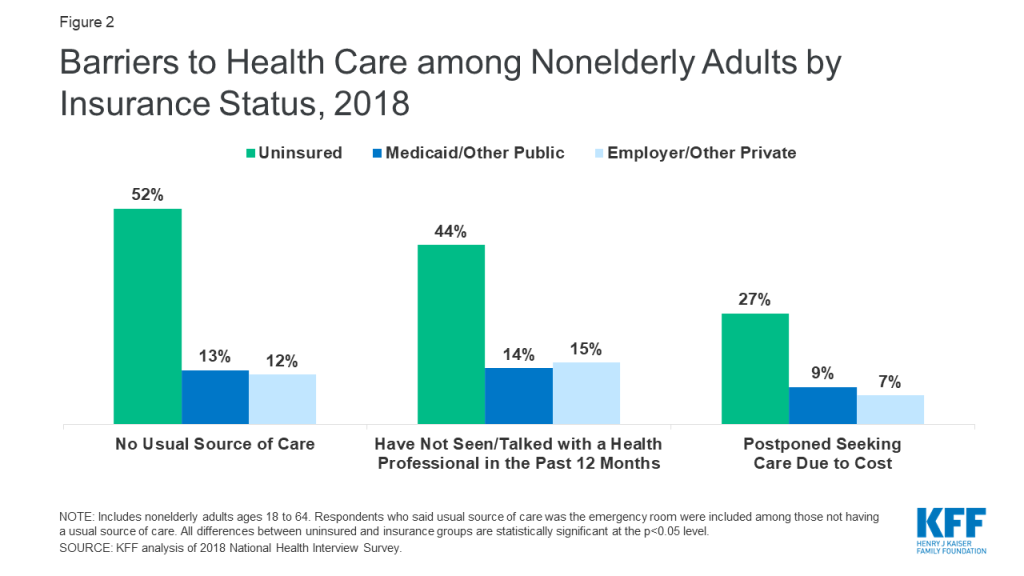

People who are uninsured will likely face unique barriers accessing COVID-19 testing and treatment services. Over half of the uninsured do not have a usual place to go when they need medical care, and one in five uninsured adults in 2018 went without needed medical care due to cost (Figure 2). Studies repeatedly demonstrate that uninsured people are less likely than those with insurance to receive services for major health conditions and chronic diseases. Without a usual source of care, the uninsured may not know where to go to get tested if they think they have been exposed to the virus and may forego testing or care out of fear of having to pay out-of-pocket for the test. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act requires hospitals to screen and stabilize patients with emergent conditions, however, they are not required to provide the care at no cost for patients who cannot pay, and they are not required to provide treatment for non-emergent conditions. As a result, uninsured individuals are less likely to use the emergency department than people with insurance, and the high costs of ED care may dissuade those without coverage from seeking care in that setting.

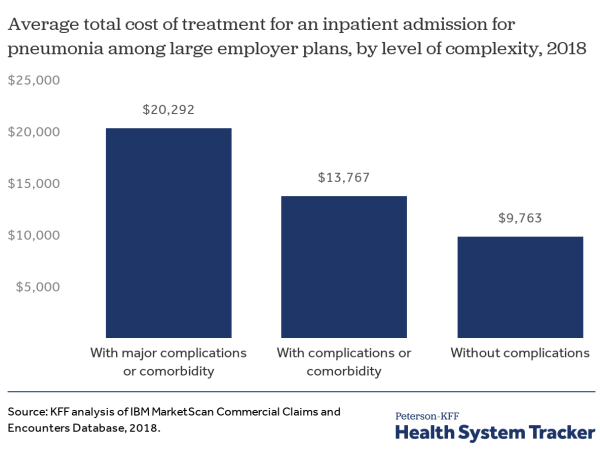

Uninsured individuals who contract COVID-19 and need medical care will likely receive large medical bills, even if they have low incomes and are unable to pay. When uninsured individuals need medical care, the costs can be prohibitive. Uninsured people pay the full cost of care, often at higher rates than those with insurance whose coverage may negotiate lower rates than a hospital otherwise charges. While some uninsured can get care at community health centers and other safety net providers, these providers have limited resources and capacity, and not all uninsured have geographic access to a safety net provider. Because the U.S. lacks a comprehensive hospital charity care policy, uninsured individuals who use hospital care will be billed for the services. Uninsured individuals who meet certain criteria may qualify for a hospital’s charity care program to reduce any hospital bills; however, not all hospitals are required to offer charity care programs, and among those that do, the eligibility criteria can vary widely. Fear of large and unaffordable medical bills can deter uninsured individuals from getting the care they need. In the context of a public health emergency, decisions to forego care because of costs can have devastating consequences.

Options for Reducing Barriers to COVID-19 Testing and Treatment

Federal legislation enacted in response to the coronavirus crisis ensures free testing for uninsured individuals. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act signed into law on March 18, 2020 includes a provision that gives states the option to expand Medicaid coverage to uninsured individuals in their state to provide coverage for COVID-19 diagnosis and testing with 100% federal financing. Although the coverage is limited to testing services, it will ensure more uninsured can access free testing, since the legislation also requires state Medicaid programs to cover diagnosis and testing for COVID-19 with no cost sharing. The legislation also appropriates $1 billion to the National Disaster Medical System to provide reimbursement to providers for the costs associated with diagnosis and testing of uninsured individuals. However, the legislation does not address coverage of COVID-19 treatment costs for people who are uninsured.

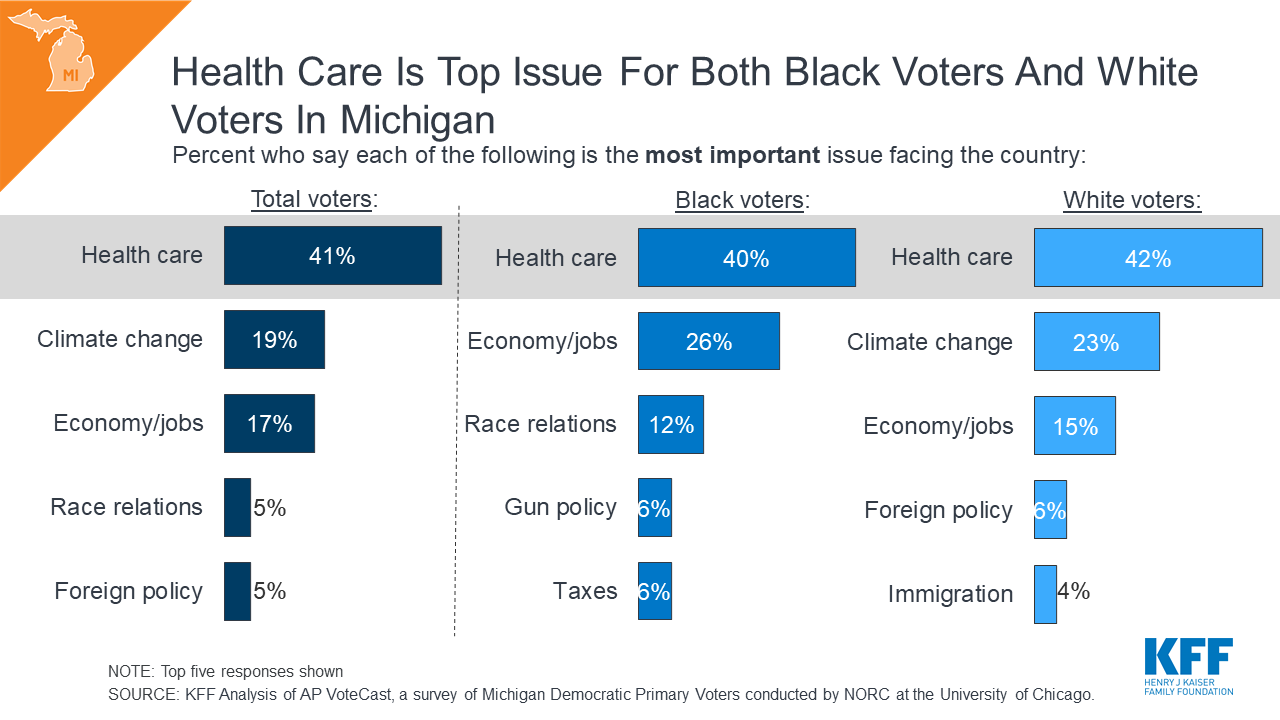

While the federal legislation will reduce barriers to COVID-19 testing, additional steps will be required to reduce barriers to accessing treatment for uninsured individuals who get sick. Expanding comprehensive coverage options to the uninsured would facilitate access to COVID-19 treatment for those who need it. Decisions by states that have not yet adopted the Medicaid expansion to do so would provide eligibility for coverage to the 2.3 million nonelderly uninsured adults in the coverage gap. In addition to adopting the Medicaid expansion, the federal government could provide flexibility to states to use Medicaid Section 1115 waiver and/or Section 1135 waiver authority to cover individuals who would not otherwise be eligible for coverage during the public health crisis, and potentially beyond. These waivers have been used in past emergencies to expand coverage. Additionally, states that operate their own health insurance marketplaces could provide a special enrollment period (SEP) in response to the coronavirus outbreak to allow uninsured individuals to enroll in coverage. Washington, Massachusetts, and Maryland recently announced coronavirus-related SEPs for uninsured residents. The federal government could also establish a national special enrollment period that would apply across all states, allowing many more uninsured to sign up for coverage.

In lieu of expanding coverage, providing funding to providers to expand COVID-19 services to uninsured individuals or to reimburse them for uncompensated costs they incur could also facilitate access to needed care. The supplemental appropriations legislation to finance the response to coronavirus included $100 million to community health centers to support increased access to testing and primary care services in medically underserved areas. However, this funding does not address costs to hospitals for treatment of infected individuals. Congress could appropriate additional funds to cover hospital costs related to treating uninsured individuals who contract the disease and need hospital care. Programs such as the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS) or Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) program could be used to reimburse hospitals for uncompensated costs; however, additional funding would be needed to cover the treatment costs related to COVID-19. Democratic Presidential candidate, Joe Biden, has proposed utilizing the NDMS by expanding its authority to reimburse providers for the costs of testing, treatment, and vaccines associated with COVID-19 for uninsured individuals and by providing full funding of those costs.