Early State Vaccination Data Raise Warning Flags for Racial Equity

The latest data on COVID-19 vaccinations by race/ethnicity is available here.

Federal data show that, as of January 19, 2021, over 12 million COVID-19 vaccines had been administered across the country. As vaccine distribution continues, ensuring racial equity will be important for mitigating the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on people of color, preventing widening health disparities, and achieving broad population immunity. Some states have centered equity as a key principle in their vaccine distribution plans. Across states, data to understand access to and uptake of the vaccine by race/ethnicity and other demographic factors will be central to efforts to ensure equity. These data are necessary to move past “color blind” policies that reinforce systematic racism and inform decisionmakers on how to develop culturally responsive interventions and direct resources to ensure equitable distribution and uptake of the vaccine. KFF is compiling and will regularly update state-reported data on vaccination by race/ethnicity through its COVID-19 state data and policy tracker.

As of January 19, 2021, 17 states were publicly reporting COVID-19 vaccination data by race/ethnicity. All but one of these states report the distribution of vaccinations by race/ethnicity, while North Dakota reports vaccination rates by racial/ethnic group. States vary in whether they report total doses administered, total first doses administered, and/or total people vaccinated by race/ethnicity.

To date, vaccination patterns by race and ethnicity appear to be at odds with who the virus has affected the most. Based on vaccinations with known race/ethnicity, the share of vaccinations among Black people is smaller than their share of cases in all 16 reporting states and smaller than their share of deaths in 15 states. For example, in Mississippi, Black people account for 15% of vaccinations, compared to 38% of cases and 42% of deaths, and, in Delaware, 8% of vaccinations have been received by Black people, while they make up nearly a quarter of cases (24%) and deaths (23%). Similarly, Hispanic people account for a smaller share of vaccinations compared to their share of cases and deaths in most states reporting data. For example, in Nebraska, 4% of vaccinations are among Hispanic people, while they make up 23% of cases and 13% of deaths. There are fewer and smaller gaps between the share of vaccinations and cases among Asian people, and data on their share of deaths remain limited. Gaps remain in data available for American Indian and Alaska Native as well as Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander people. Reflecting these trends, the share of vaccinations among White people is larger than their share of cases in 13 of the 16 reporting states and larger than their share of deaths in 9 states. For example, in Maryland, White people account for nearly two-thirds of vaccinations (65%), but 39% of cases and 50% of deaths. Similarly, in North Carolina, 82% of vaccinations have been among White people, while they make up 62% of cases and 65% of deaths.

Data also show that the shares of vaccinations among Black and Hispanic people are lower compared to their shares of the total population in most reporting states. In contrast, the share of vaccinations among White people is higher than their share of the total population in most states. While this will be an important metric to track over time, it is still early in the process to interpret these data since the vaccines are not yet broadly available to the public.

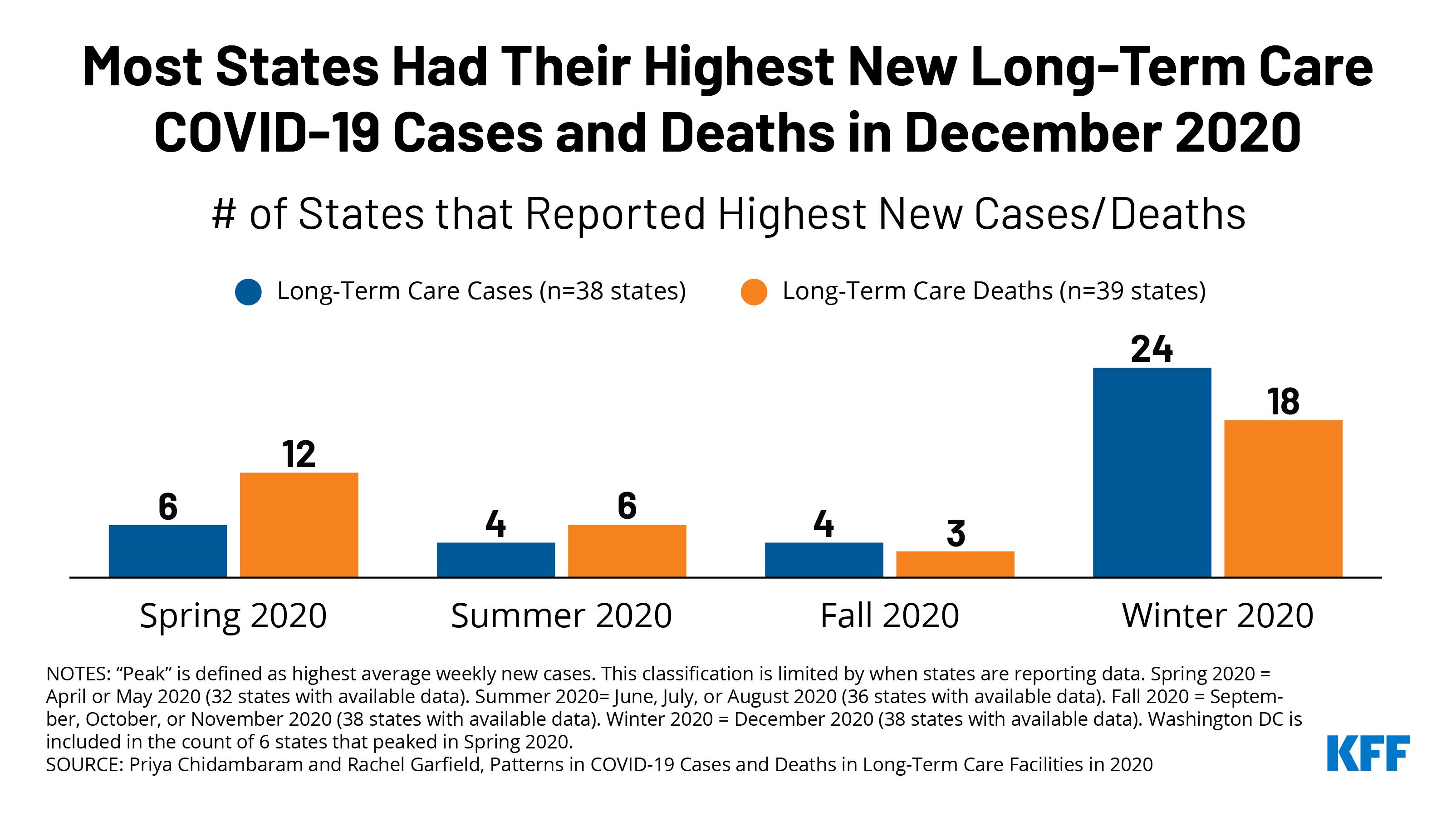

Together the data raise some early warning flags about potential racial disparities in access to and uptake of the vaccine, but it is difficult to draw strong conclusions given that the vaccines are not yet broadly available and due to data limitations. As noted, the vaccines still are not yet broadly available to the public as the early priority groups for vaccination have primarily been health care workers and long-term care residents and staff. Different patterns may emerge as the vaccines roll out more broadly. In addition, there remain gaps and inconsistencies in the data. In some states, race/ethnicity is unknown for a significant share of vaccinations, and the share unknown may not be distributed equally across racial/ethnic groups. For example, in three states (Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Tennessee), race/ethnicity is unknown for over half of vaccinations. In addition, as noted above, states vary in what vaccination data they are reporting, with some reporting doses administered and others reporting people vaccinated. States also vary in their racial/ethnic classifications, limiting the comparability of data across states. For example, some include Hispanic people in their racial categories, while others limit racial groups to non-Hispanic people. Additionally, some states report Asian and Pacific Islander people in a combined group, while others disaggregate data for Asian and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander people.

Comprehensive standardized data across states will be vital to monitor and ensure equitable access to and take up of the vaccine. Given the dearth of COVID-19 data by race/ethnicity at the outset of the pandemic, it is encouraging that some states are reporting vaccinations by race/ethnicity during this early stage of the vaccine rollout. However, most states are not yet reporting these data, and the data that are reported are incomplete and inconsistent, limiting their usefulness. In a recent KFF briefing, President Biden’s COVID-19 Equity Task Force Chair, Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, emphasized the importance of accurate, high-quality data for addressing disparities noting, “we cannot address what we cannot see.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has outlined COVID-19 vaccine data reporting and sharing requirements that include the collection of race/ethnicity data. However, since “unknown” or “unable to report due to policy or law” are response options, data completeness will hinge on collection efforts, which may vary across states and providers given potential burdens and challenges associated with collecting it.

KFF will keep a close eye on vaccination data going forward and continue to report additional state and national data as they become available.