COVID-19 Vaccination among American Indian and Alaska Native People

Summary

With the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine underway, ensuring equitable and rapid distribution to the U.S. population will be important for mitigating the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic for people of color, preventing widening racial health disparities going forward, and achieving broad population immunity. Reflecting underlying inequities, the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected American Indian and Alaskan Native (AIAN) people who account for over 5 million people in the U.S. At the same time, vaccination rates among AIAN people have been higher than average to date. This brief presents available data on COVID-19 vaccinations among AIAN people from federal and state sources and discusses factors contributing to success in these vaccination efforts. It finds:

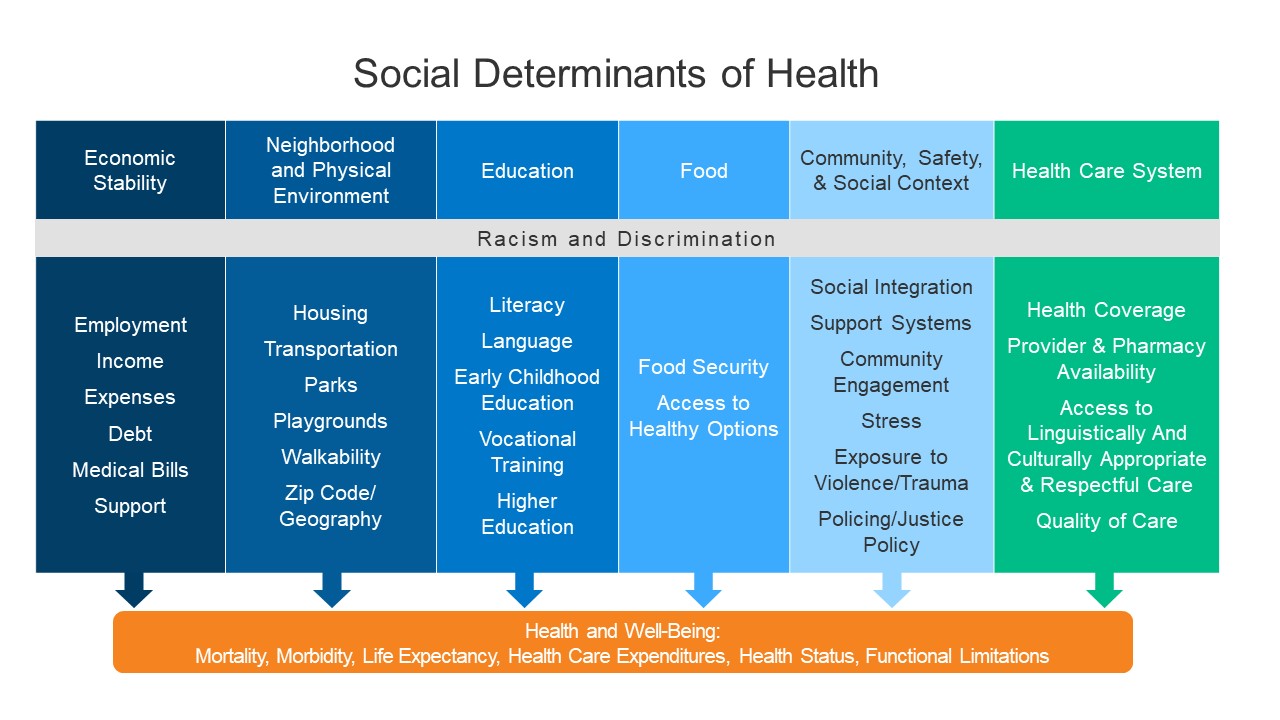

Underlying inequities that existed prior to the pandemic contribute to AIAN people facing increased barriers to accessing health care and being disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Chronic underfunding of the Indian Health Service (IHS) relative to health needs and high uninsured rates contribute to barriers to health care among AIAN people. Existing social, economic, and health inequities have also led to higher rates of illness and death among AIAN people due to COVID-19.

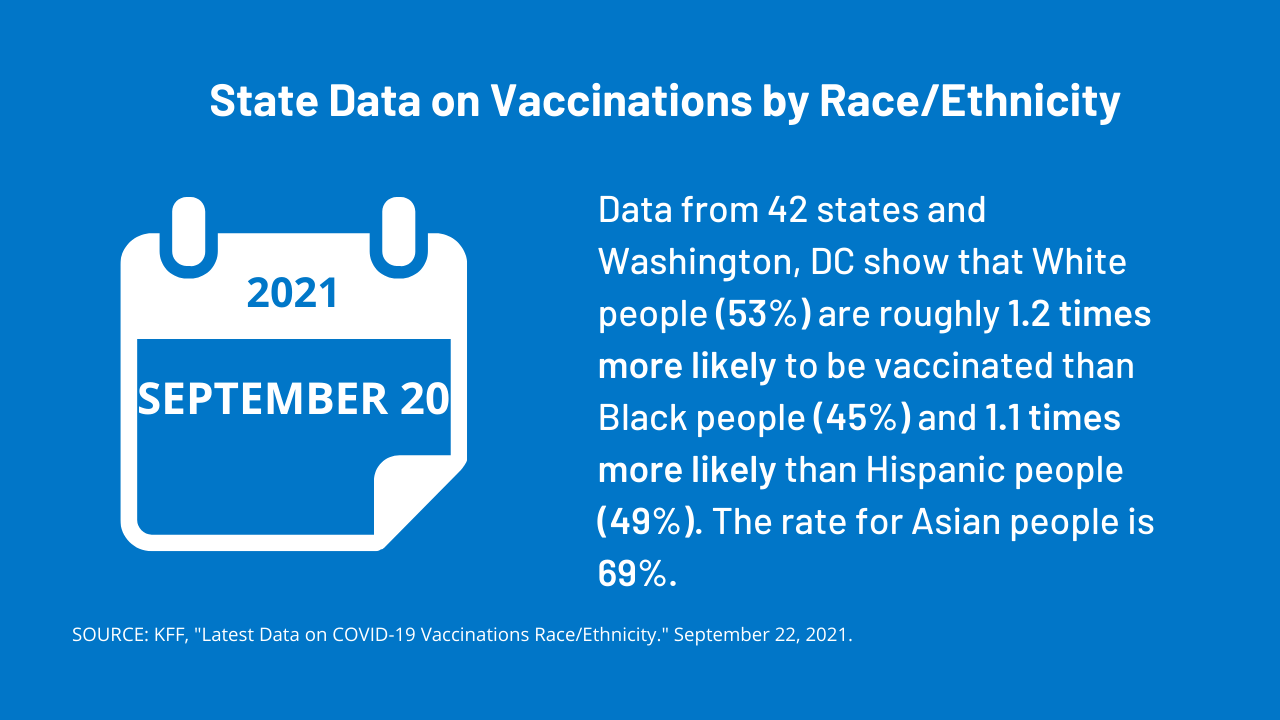

Data available to date show that AIAN people are being vaccinated at a higher rate compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Federal data show that 32% of AIAN people had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, compared to 19% of White people, 16% of Asian people, 12% of Black people and 9% Hispanic people of as of April 5, 2021.State data similarly find higher vaccination rates among AIAN people compared to other groups.

The high vaccination rate among AIAN people largely reflects Tribal leadership in implementing vaccine prioritization and distribution strategies that meet the preferences and needs of their communities. The high rates may also, in part, reflect the greater supply of vaccine doses delivered to the IHS relative to the number of people served compared to state vaccination programs. Tribes have supported and built on existing trusted community resources and providers to distribute vaccines. The success Tribes have achieved in vaccinating their communities provide lessons learned that may help inform broader vaccination efforts going forward.

Background: Health and Health Care for AIAN People

Under treaties and laws, the federal government has a unique responsibility to provide health care services to AIAN people. The IHS is the primary vehicle through which the federal government fulfills this responsibility for members of federally recognized tribes, who make up approximately 2.6 million of the over 5 million individuals who self-identify as AIAN nationwide. The IHS provides services directly, through Tribally operated health programs, and through services purchased from private providers. The IHS also funds Urban Indian Organizations to make health care services accessible to people who reside in urban areas, who include most of the AIAN population.

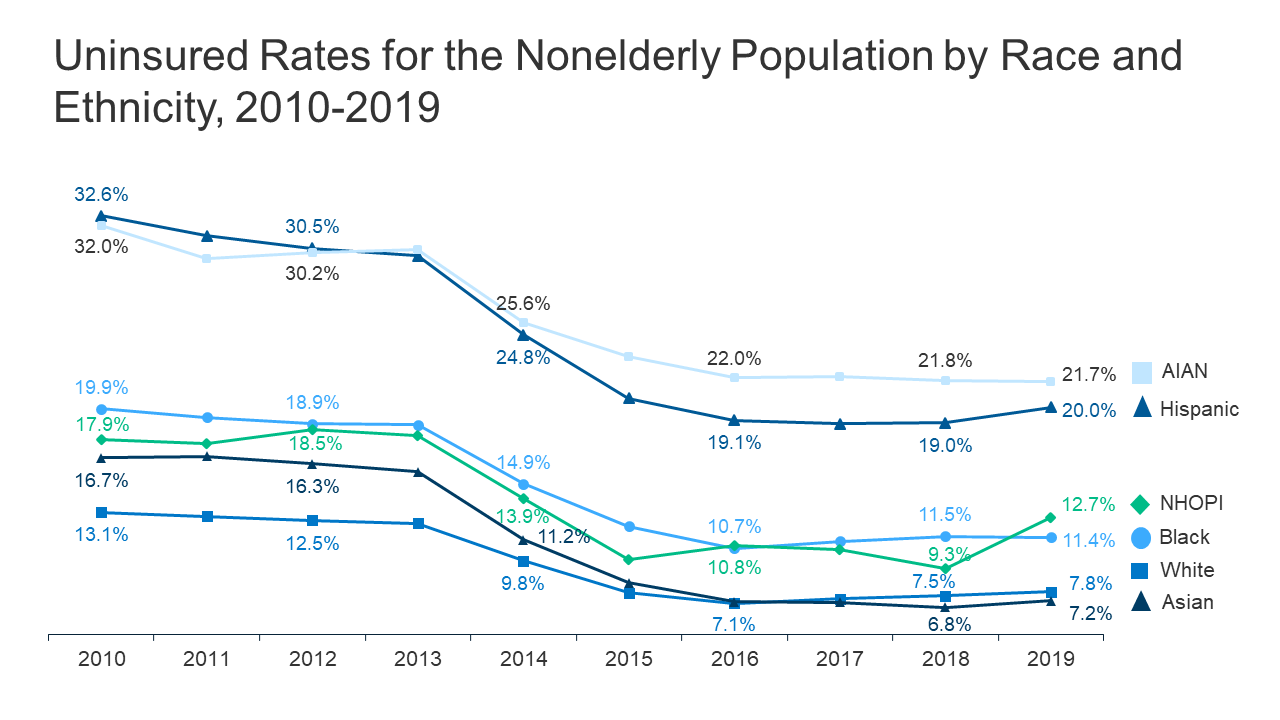

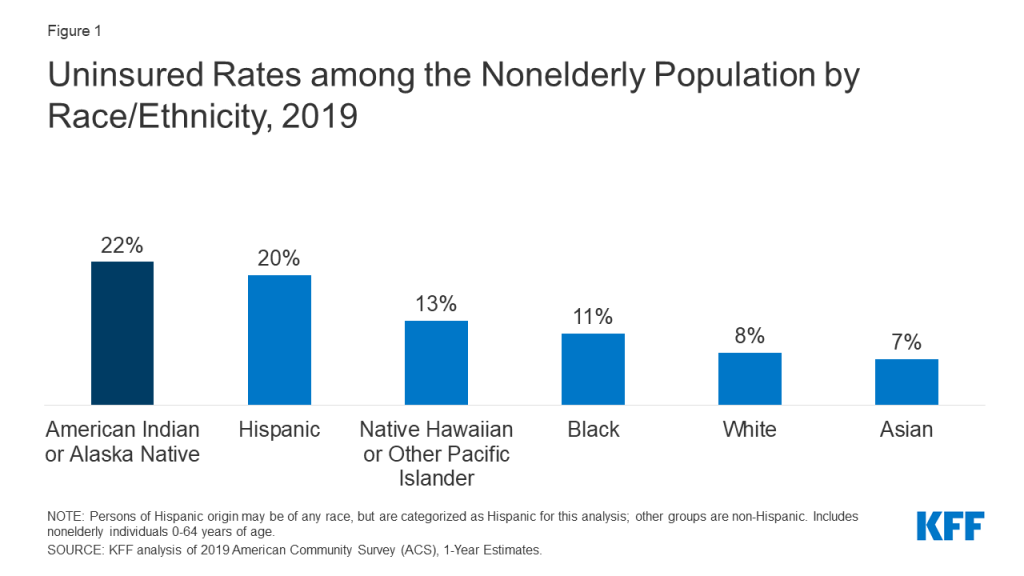

Due to longstanding limitations and underfunding of the IHS, AIAN people face disproportionate barriers to accessing health care. IHS services generally are limited to members of or descendants of members of federally recognized Tribes, and not all individuals who self-identify as AIAN belong to one of these Tribes. IHS historically has been underfunded to meet the health care needs of AIAN people, and access to services through IHS often varies across locations. Given the limitations of IHS, Medicaid and other sources of health insurance remain important for expanding access to care for AIAN people. However, as of 2019, 22% of AIAN nonelderly people were uninsured, the highest of all racial and ethnic groups (Figure 1).

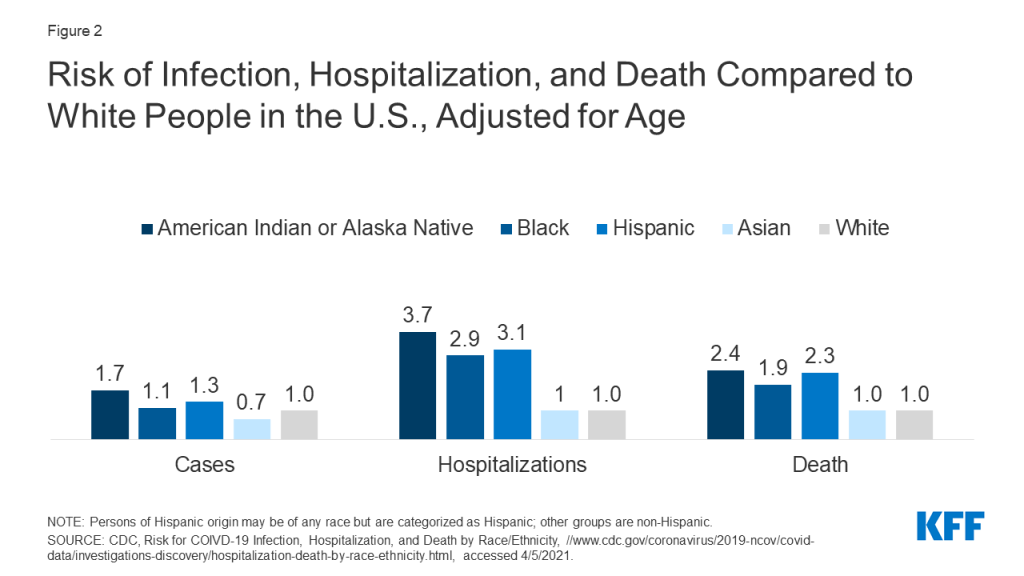

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected AIAN people. AIAN people face increased risk of exposure to the virus to due underlying social and economic factors and have higher high rates of health conditions that put them at increased risk for serious illness if they contract coronavirus. Reflecting these increased risks, AIAN people are nearly twice as likely to be infected with the virus, nearly four times likely to be hospitalized, and nearly two and half times as likely to die due to COVID-19 as their White counterparts, based on age-adjusted data (Figure 2).

COVID-19 Vaccination among AIAN People

The federal government is allocating COVID-19 vaccines directly to the IHS, and Tribal health programs and Urban Indian Organizations choose whether to receive vaccines directly from the IHS or through their respective state distribution mechanisms. As of March 15, 2021, 351 of the 609 IHS facilities, Tribal health programs, and Urban Indian Organization facilities had elected to receive vaccines directly through IHS; facilities can change their election. When Tribal health programs and Urban Indian Organizations elect to receive vaccines through the state, the CDC provides the state a “sovereign nation supplement” of vaccine doses. CDC data shows that as of April 5, 2021, nearly 1.5 million vaccine doses had been delivered to IHS, over 1 million doses had been administered via IHS, and more than 630,000 people had received at least one dose through IHS, making up over 30% of the population served by IHS.

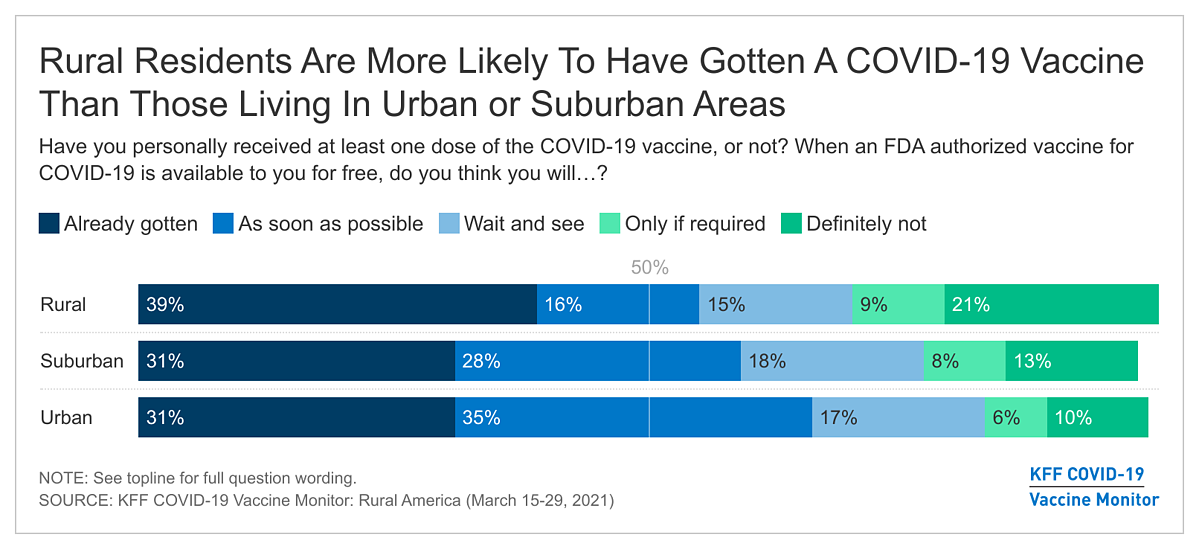

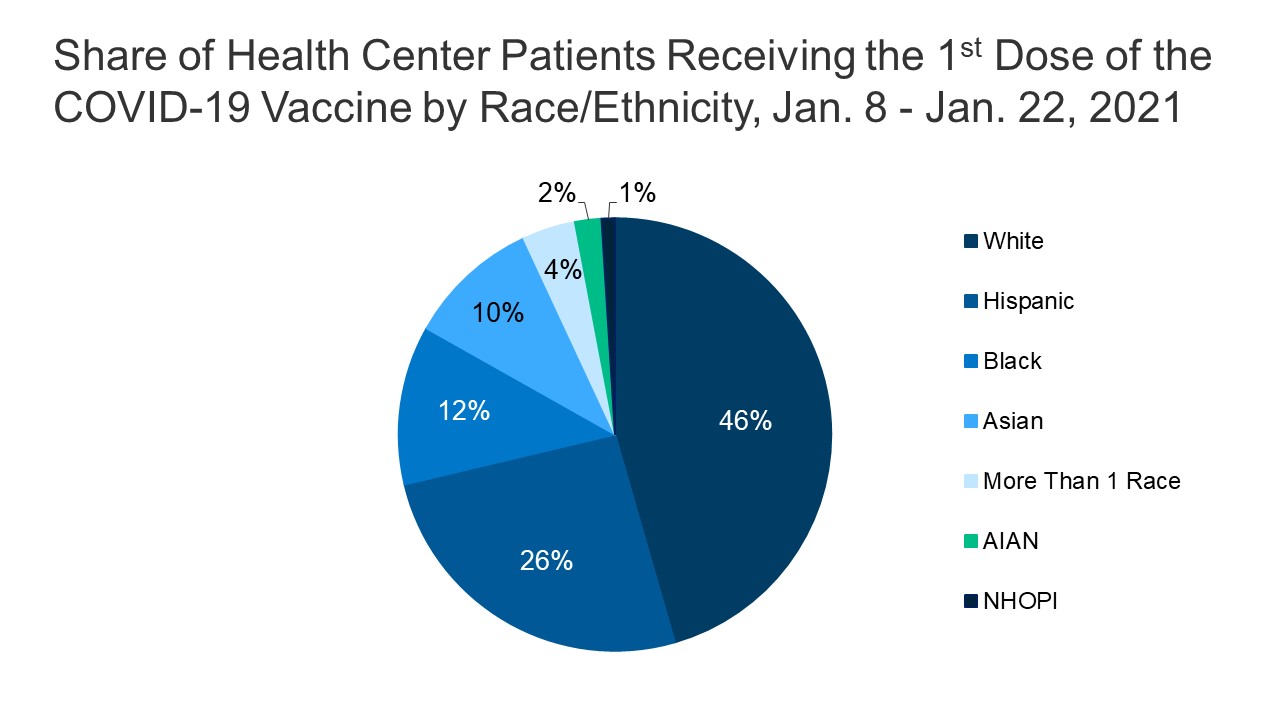

Data available to date suggest that AIAN people are being vaccinated at a higher rate compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Data gaps limit the ability to have a complete picture of who is being vaccinated and how vaccination rates vary across groups. However, data available to date show that AIAN people are being vaccinated at a higher rate relative to other racial/ethnic groups. For example, federal data from CDC, which were available for about half of people who have received at least one dose as of April 5, 2021, suggest that over 720,000 AIAN people had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, making up over 30 percent of the 2.2 million people who self-identify solely as AIAN (Figure 3). In contrast, these data show 19% of White people, 16% of Asian people, 12% of Black people, and 9% of Hispanic people had received at least one vaccine dose.

State-level data on vaccinations among AIAN people is limited. Only 36 states were reporting vaccinations among AIAN people as of March 29, 2021. Moreover, the state-reported data does not reflect vaccines administered through allocations received through IHS, and, as such, may understate vaccination rates and further limit the ability to calculate reliable estimates. However, data from several states show that AIAN people are being vaccinated at higher rates compared to other groups. For example, in Alaska, 22% of vaccinations have gone to AIAN people while they account for 15% of the population. The pattern is similar at the county-level. As of April 5, 2021, counties with high shares of AIAN people had a higher average vaccination rate (20%) when compared to the average across counties and counties with low shares of AIAN people (19% and 18%, respectively).1

Factors Contributing to High AIAN Vaccination Rates

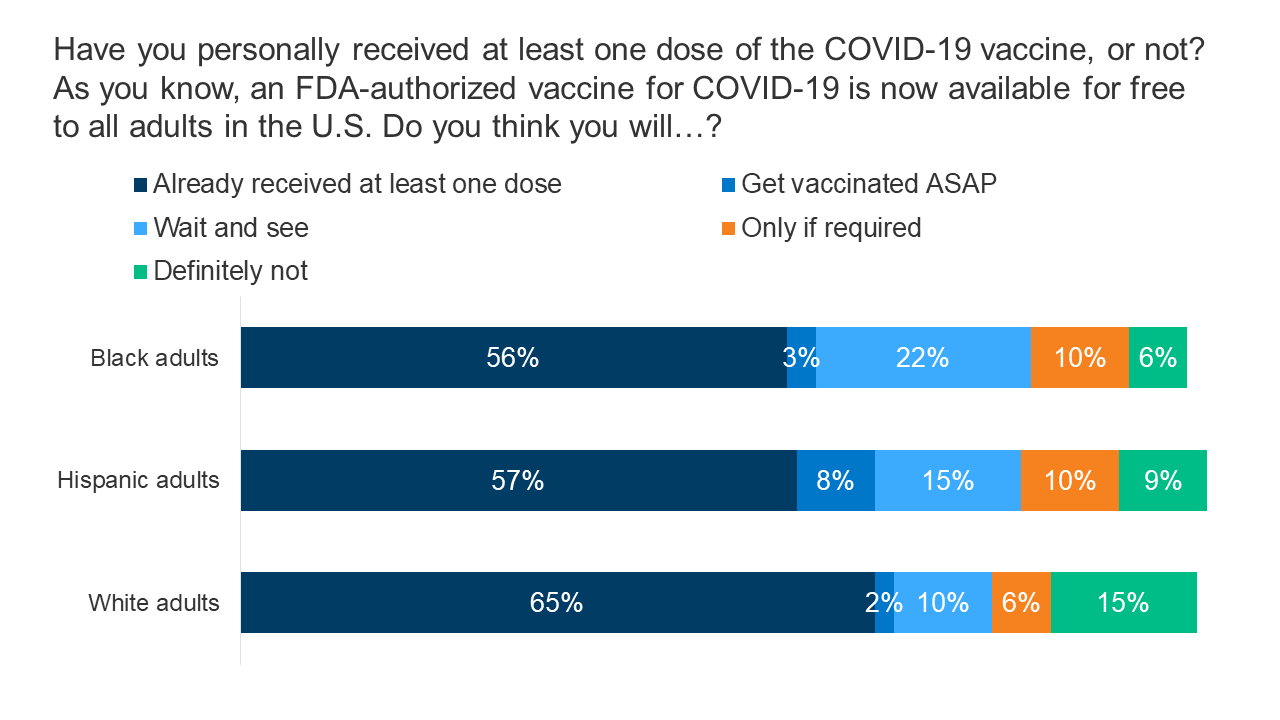

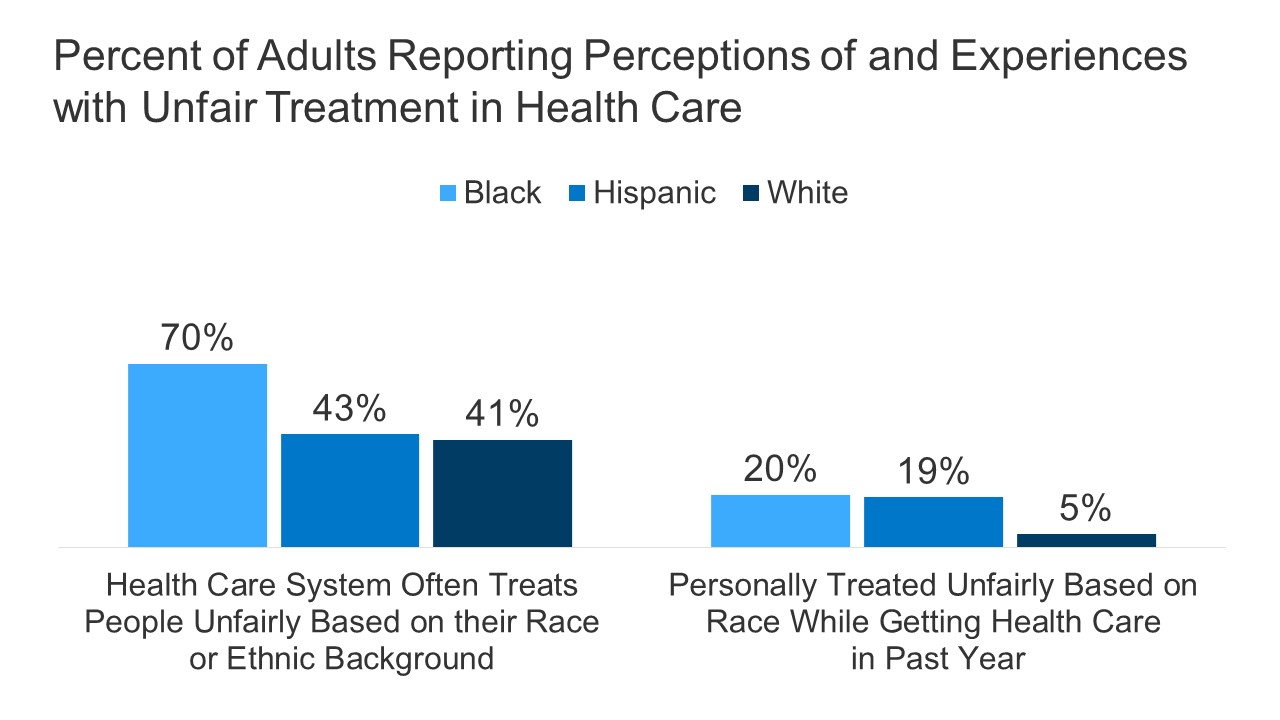

The high vaccination rate among AIAN people stands in stark contrast to the gaps in vaccinations for Black and Hispanic people observed to date. The underlying inequities and barriers to health care facing AIAN people similarly could have led to barriers to vaccination. However, experiences suggest that the autonomy provided to Tribes to design and implement vaccine distribution efforts among their communities has contributed to success in vaccinating the population. The high rates may also, in part, reflect the greater supply of vaccine doses delivered to the IHS relative to the population served compared to state vaccination programs. As of April 5, 2021, over 1.5 million doses had been delivered to IHS, which represents roughly nearly 75,000 per 100,000 people served by the IHS. Only 2 states and Washington DC had higher rates of doses delivered than the IHS, although the IHS rate of doses administered is lower compared to these states. Additionally, the availability of more complete race/ethnicity data for AIAN people receiving the vaccine, since many are receiving it through IHS, Tribal health, and Urban Indian Organization facilities, may also be contributing to the high rates. Federal and some state data have high shares of vaccinations with unknown or “other” race/ethnicity, which may affect vaccination rates across racial/ethnic groups.

IHS, Tribal health programs, and Urban Indian Organizations have autonomy and flexibility to implement priority and distribution strategies that meet the needs and preferences of their communities. The IHS developed a COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force (VTF) to advance plans for prioritization strategies, vaccine administration, distribution, data management, safety and monitoring, and communications. Consistent with the federal recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Policies (ACIP), IHS first prioritized health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities. Initial doses allocated to IHS were estimated to be sufficient for 100% of its health care workforce and residents of long-term care facilities. Like states, Tribes and Urban Indian Organizations have authority to make their own prioritization decisions. Many chose to prioritize elders and some, like the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, prioritized speakers of native languages, to protect against further losses of culture and traditions that the pandemic has threatened. Several Tribes, including Chickasaw Nation, Cherokee Nation, and Lummi Nation, have already had so much success in vaccinating their priority groups that they have expanded distribution to include non-Native members of the public.

Tribes are building on and supporting existing trusted community resources and providers to distribute vaccines. Tribes are utilizing the networks and resources in the community and drawing upon years of experience to reach tribal members with various access barriers. For example, the Navajo Nation has vaccinated between 4,000 and 5,000 homebound citizens by collaborating with public health workers to reach those residents in rural communities. In Alaska, tribal health organizations relied on longstanding strategies developed to reach geographically isolated communities, including partnering with local pilots to transport pharmacists and vials of vaccines to such areas. In addition, many Tribes have established vaccine sign-up systems that match the resources and preferences of their populations. For example, media reports suggested that many Tribes have set up call centers to answer inquiries, book appointments, and reach out to people.

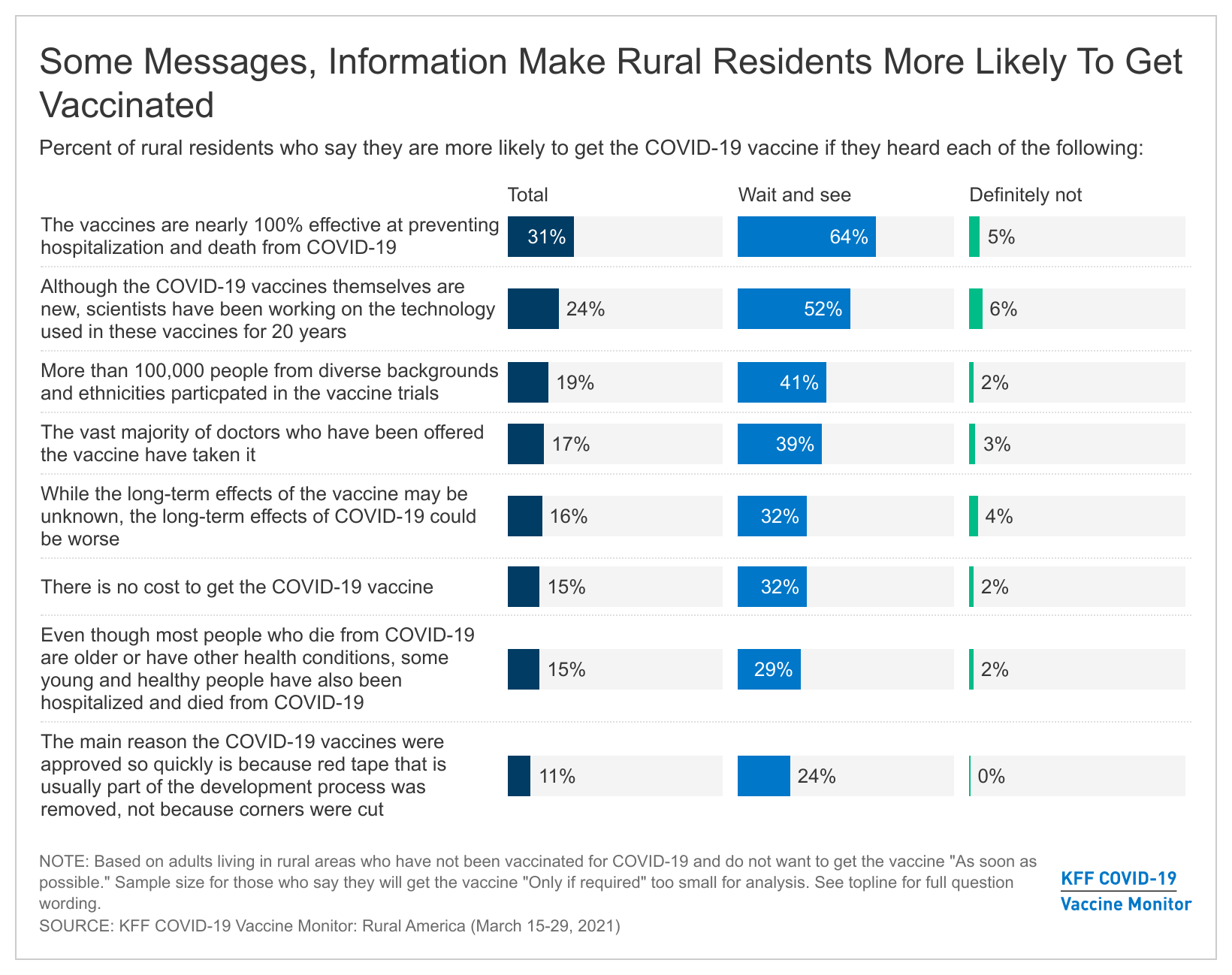

Tribes have launched tailored outreach and communication plans that share culturally relevant messages through trusted individuals in the community. A national survey of AIAN people conducted in late 2020 found that the majority were willing receive a COVID-19 vaccine and that the most commonly held motivation for getting a vaccine was a sense of responsibility to protect the Native community and preserve cultural ways. Regardless of willingness to get a vaccine, the most frequently reported concern about the vaccine was how fast the vaccine moved through clinical trials. Some Tribes have utilized fluent language speakers to address concerns about the vaccine among the community. For example, the Cherokee Nation prioritized Cherokee language speakers to create optimism and show that the vaccine was safe. Similarly, the Navajo Nation employed fluent doctors and health care professionals to serve as trusted sources of information on the vaccine.

Looking Ahead

Given the disparate impacts of COVID-19 on AIAN people and the barriers and challenges they face to accessing health care, ensuring access to the COVID-19 vaccine is particularly important. Data available to date show a high COVID-19 vaccination rate among AIAN people, largely reflecting the role of Tribes in designing and implementing vaccine distribution strategies that meet the needs and preferences of the communities they serve. The success Tribes have achieved in vaccinating their communities provide lessons learned that may help inform broader vaccination efforts going forward. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides IHS with an additional $600 million for vaccine efforts, $1.5 billion to trace COVID-19 infections, $240 million to establish and sustain a COVID-19 public health workforce, and $600 million for COVID-19 related facility improvements, which may further enhance Tribal vaccination efforts and their response to COVID-19.

- KFF analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) COVID-19 Integrated County View data. Counties in which the share of AIAN people is above the national average of 0.7% were classified as counties with high shares of AIAN people. Of the 2,350 reporting counties, 617 fall into the high share of AIAN people category (26% of the counties). ↩︎