KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: What We’ve Learned

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project tracking the public’s attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and qualitative research, this project tracks the dynamic nature of public opinion as vaccine development and distribution unfold, including vaccine confidence and acceptance, information needs, trusted messengers and messages, as well as the public’s experiences with vaccination.

KFF launched the COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor in December 2020 to track the dynamic nature of the U.S. public’s attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccination as distribution efforts unfold across the country. As many states have opened up eligibility to everyone ages 16 and over and the remainder of states are poised to do so soon, this brief summarizes some of the key findings and themes from this research based on interviews with more than 11,000 adults across the nation to date.

Key takeaways

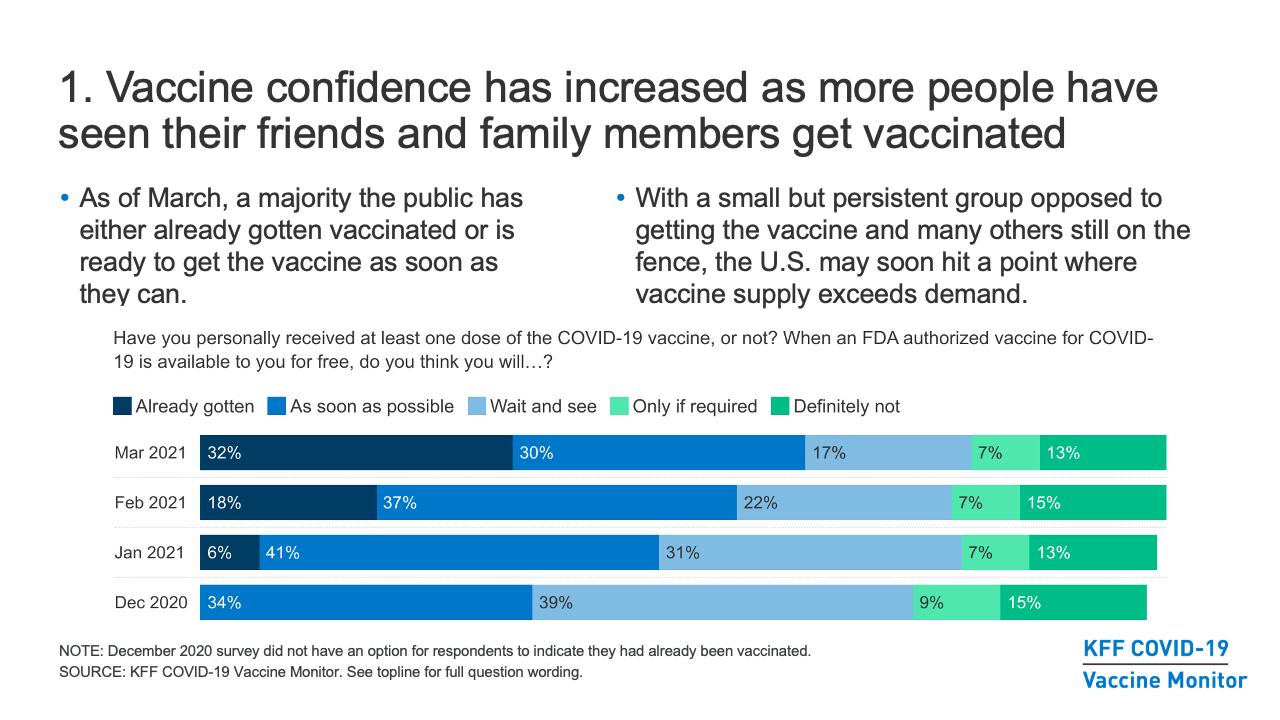

- Broadly, the COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor has found that vaccine confidence in the U.S. has increased as more and more people have seen their friends and family members get vaccinated, and now a majority of the public has either already gotten vaccinated or is ready to get the vaccine as soon as they can. Yet with a small but persistent group opposed to getting the vaccine and many others still on the fence, the U.S. may soon hit a point where vaccine supply exceeds demand, a situation that is already the case in certain communities.

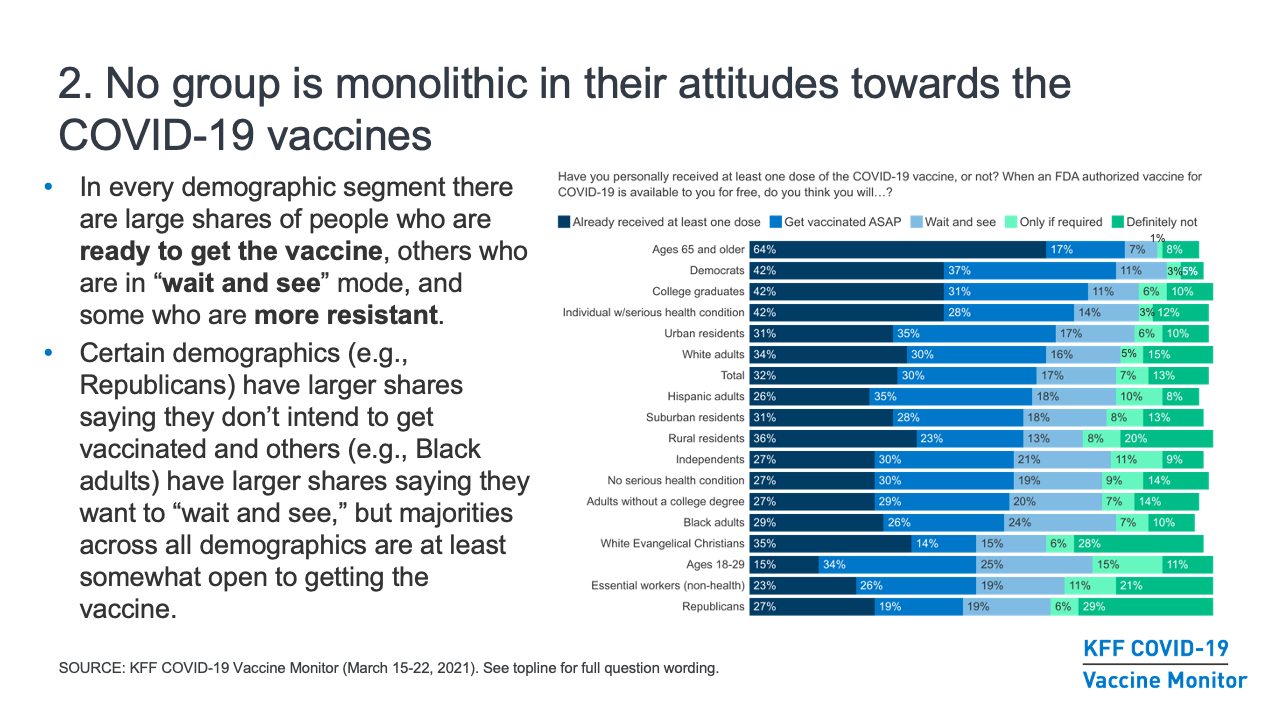

- While some media narratives have focused on which groups are most “vaccine hesitant,” our research finds that no group is monolithic in their vaccine attitudes, and in every demographic segment there are large shares of people who are ready to get the vaccine, others who are in “wait and see” mode, and some who are more resistant. Even though certain demographics (for example, Republicans) have a higher share than other groups saying they don’t intend to get vaccinated and others (for example, Black adults) have a higher share saying they want to “wait and see,” we’ve found that majorities across all demographic groups are at least somewhat open to getting the vaccine.

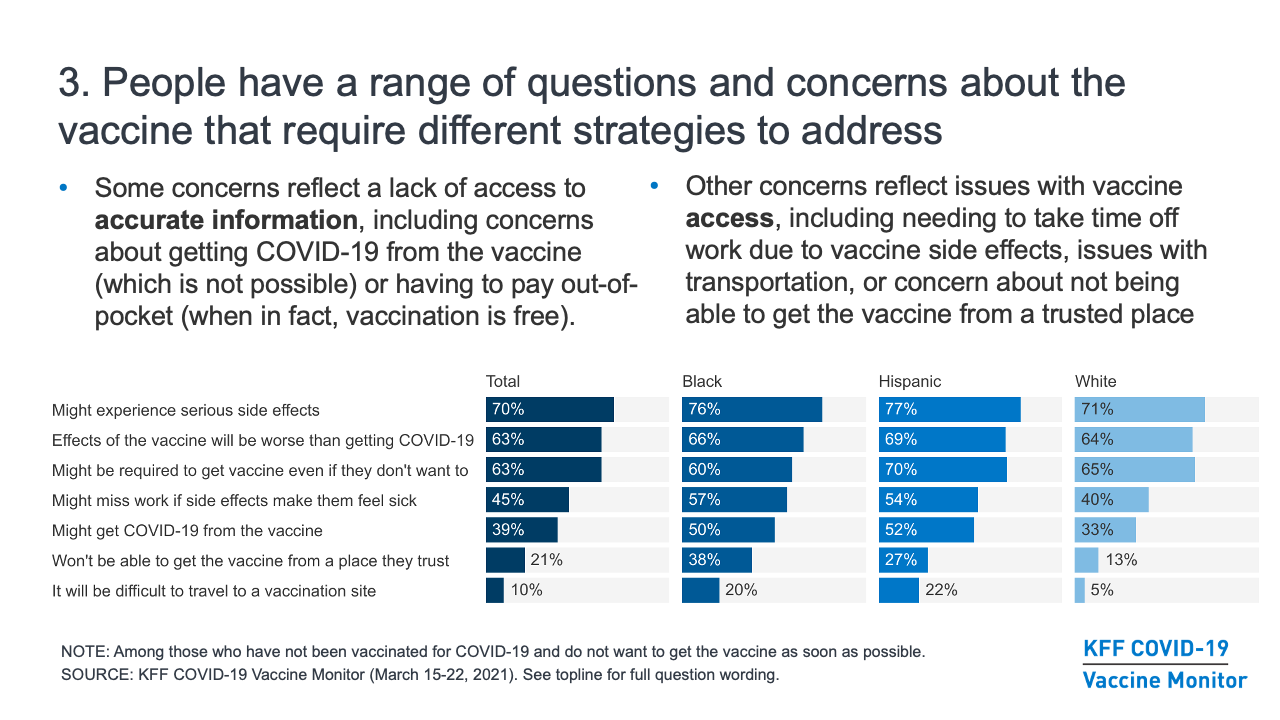

- Those who are not ready to get vaccinated for COVID-19 right away have a range of questions and concerns about the vaccine that require different strategies to address. The top concern across groups has been the potential side effects of the vaccine, including a substantial share who are worried about missing work due to side effects. Other concerns reflect a lack of access to accurate information; for example, many are concerned that they might get COVID-19 from the vaccine (which is not possible) or that they will have to pay out-of-pocket costs to get vaccinated (when in fact, vaccination is free). And other concerns reflect issues with vaccine access, including needing to take time off work to get vaccinated, issues with transportation, or concern about not being able to get the vaccine from a trusted place. Rather than a single messaging strategy, these concerns point to the need for a combination of information, outreach, and policies to both bolster confidence in COVID-19 vaccines and make vaccination accessible across communities.

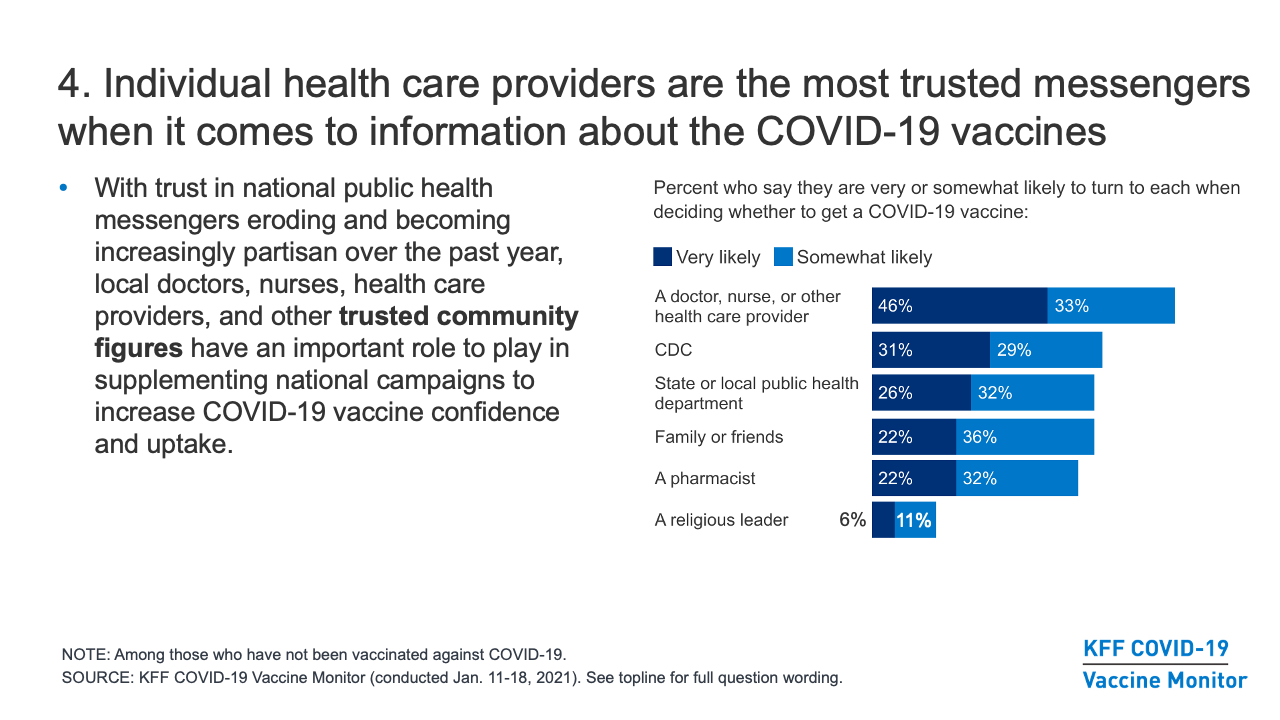

- Individual health care providers are the most trusted messengers when it comes to information about the COVID-19 vaccines. With trust in national public health messengers eroding and becoming increasingly partisan over the past year, local doctors, nurses, health care providers, and other trusted community figures have an important role to play in supplementing any national campaigns to increase COVID-19 vaccine confidence and uptake.

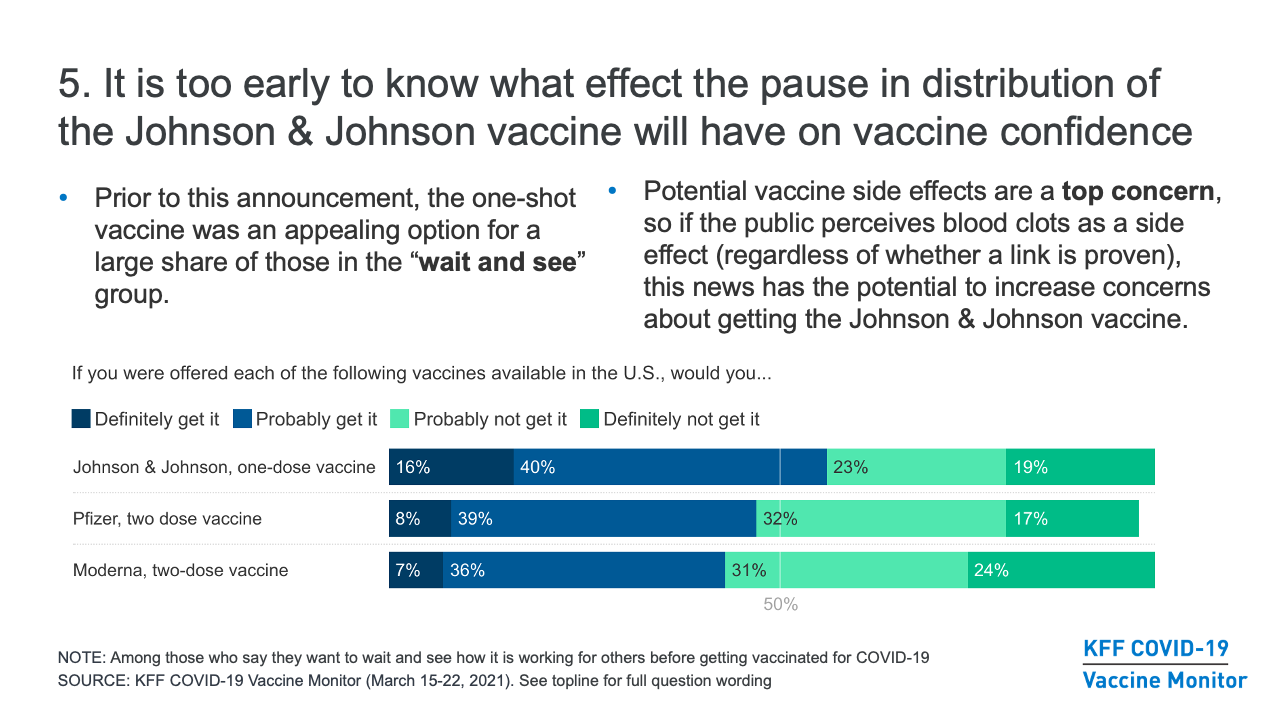

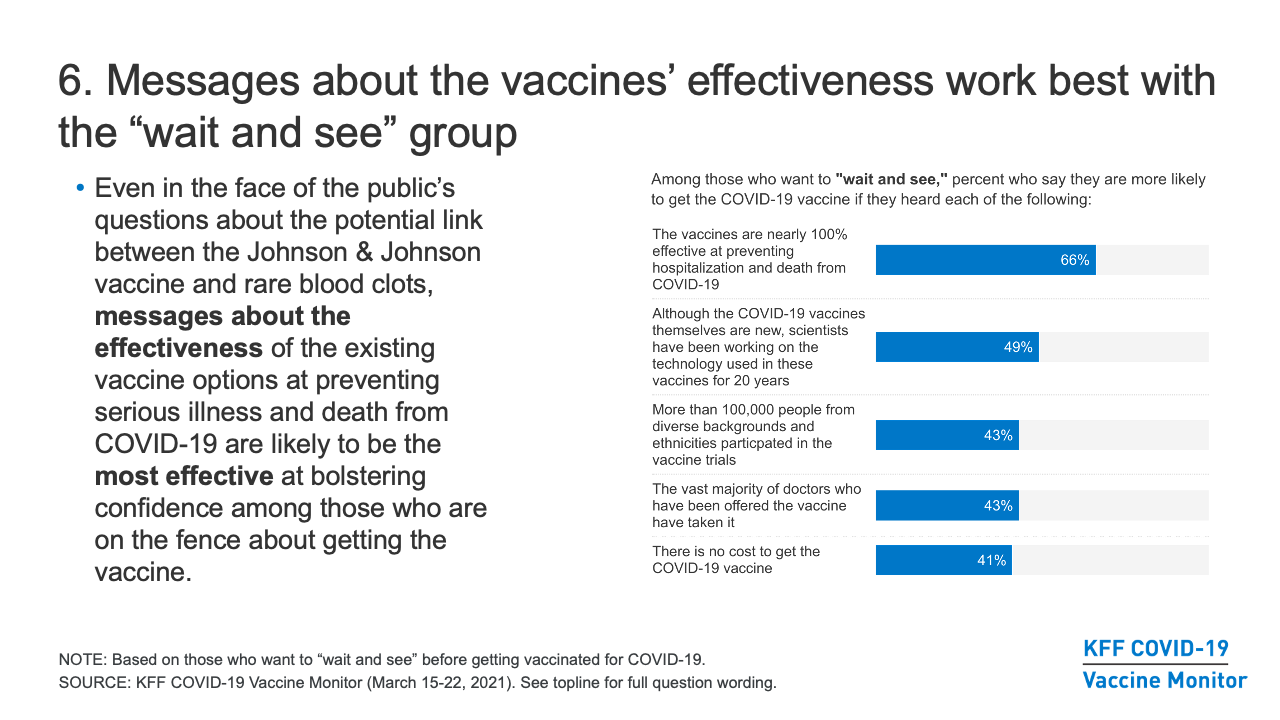

- It is too early to know what effect the recent announcement about the pause in distribution of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine will have on COVID-19 vaccine confidence. Prior to this announcement, our research found that the one-shot vaccine was an appealing option for a large share of those in the “wait and see” group. However, the potential side effects of the vaccine are a top concern for those who have not yet been vaccinated, so if the public perceives blood clots as a potential side effect (regardless of whether a link is proven), this news does have the potential to increase concerns about getting the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. In the meantime, messages about the effectiveness of the existing vaccine options at preventing serious illness and death from COVID-19 are likely to be the most effective at bolstering confidence among those who are on the fence about getting the vaccine.

Vaccination intentions: trends and demographics

- The share of the public that is eager to get the COVID-19 vaccine has been increasing over time, including across subgroups by race/ethnicity, partisanship, and urbanicity. As of March, six in ten adults said they had already gotten at least one dose of the vaccine (32%) or would get it as soon as it was available to them (30%), a share that has increased steadily since December, when 34% said they would get the vaccine as soon as possible. The share saying they want to “wait a while and see how it’s working for others” before getting vaccinated themselves declined steadily from 39% in December to 17% in March. Where we have not yet seen much movement is in the shares saying they definitely won’t get the vaccine (13% in March) or will do so only if required for work, school, or other activities (7%).

- People at higher risk for serious complications and death from COVID-19 tend to be more enthusiastic about getting the vaccine. For example, in March, 82% of adults ages 65 and older and 70% of individuals with a serious health condition say they’ve already been vaccinated or will get the vaccine as soon as they can, compared to smaller shares of younger adults and those without serious health conditions. This at least partially reflects early access these groups had to the vaccine compared to others, but also the fact that larger shares of younger and healthier adults say they want to wait and see, will get the vaccine only if required, or will definitely not get vaccinated.

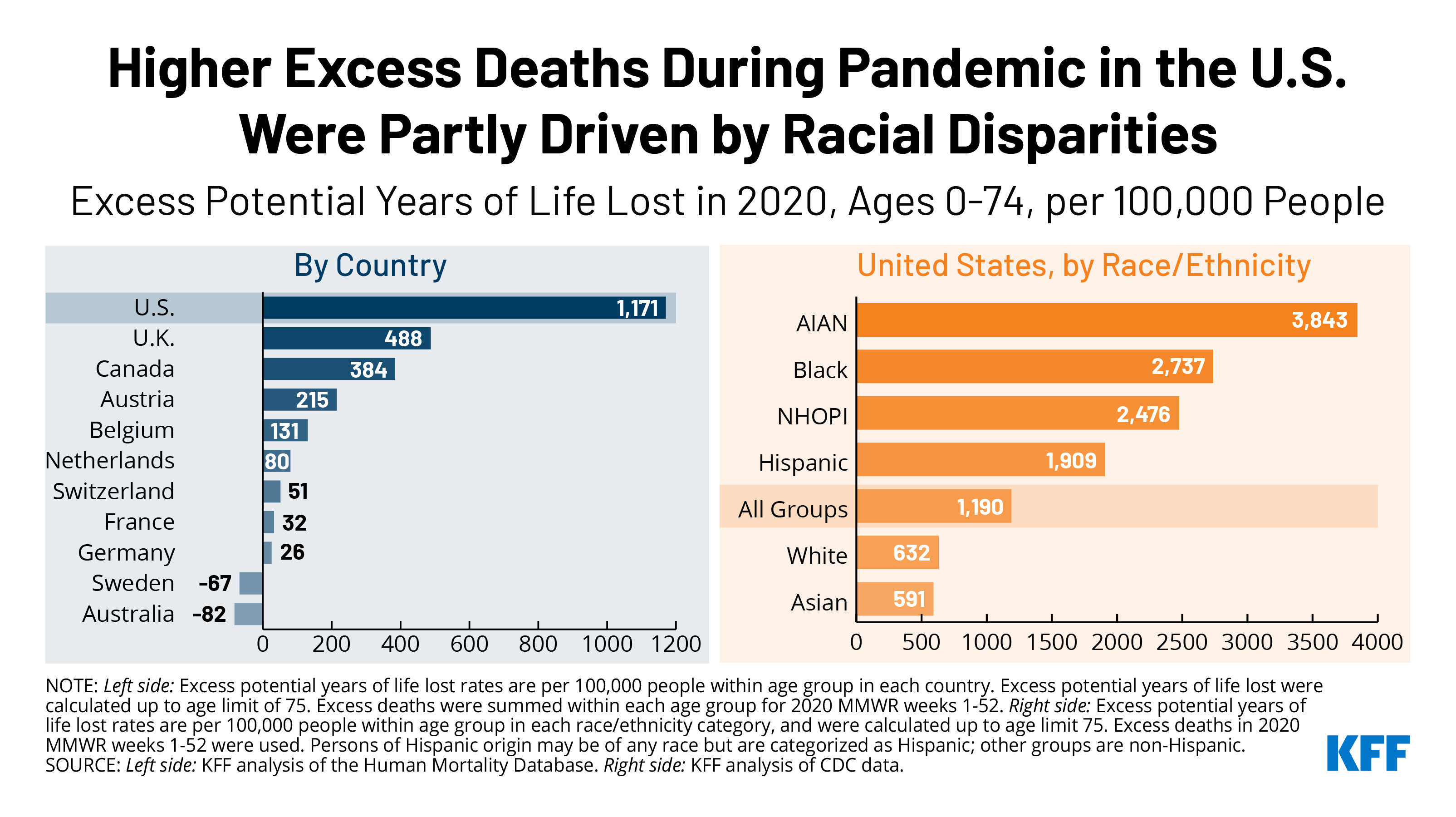

- While enthusiasm for getting the vaccine increased dramatically among Black adults between February and March (from 41% to 55% saying they’d already gotten vaccinated or intended to do so as soon as possible), Black adults remain somewhat more likely than White adults to say they want to “wait and see” (24% vs. 16%). In earlier months, Hispanic adults were also somewhat more likely to say they wanted to “wait and see,” but by March the share among Hispanic adults decreased to 18%.

- Education is also a dividing factor in vaccination intentions, with college-educated adults more likely than those without college degrees to say they’ve already gotten vaccinated or will do so as soon as they can (73% vs. 56% in March).

- Vaccination intentions have also divided along party lines since December, reflecting the broader partisan dialogue about the pandemic over the past year. About eight in ten Democrats (79%) are eager to get the vaccine or say they have done so already, compared to nearly six in ten independents (57%) and just under half of Republicans (46%). About three in ten Republicans (29%) say they will “definitely not” get vaccinated, a share that has not changed substantially over time.

- In addition, 28% of White Evangelical Christians say they will definitely not get the vaccine, reflecting the fact that two-thirds (66%) of this group either identifies as Republican or leans towards the Republican party. One in five rural residents also say they will definitely not get vaccinated, about twice the share as in urban areas, a gap largely explained by the concentration of Republicans and White Evangelical Christians who live there.

Challenges and opportunities that cross demographic groups

Concerns and messages

- The potential side effects and the newness of the vaccine seem to be driving a lot of the concern among people who have not yet been vaccinated. Among the 37% of adults in March who were not yet convinced to get the vaccine as soon as possible, seven in ten said they were concerned they might experience serious side effects from the vaccine, and over six in ten were concerned the effects of the vaccine might be worse than getting COVID-19. In addition, when those who say they will definitely not get the vaccine are asked to state their main reason in their own words, the most common response is that the vaccine is too new and/or that not enough is known about the long-term effects.

- Different groups respond to messaging and information at different levels, but of the messages we’ve tested, emphasizing the effectiveness of the vaccine at preventing serious illness and death is the most effective across groups (two-thirds of those in the “wait and see” group and four in ten in the “only if required” group say they’d be more likely to get vaccinated after hearing the vaccines are nearly 100% effective at preventing hospitalizations and death from COVID-19).

- The “wait and see” group is an important target for outreach and messaging, since they express some concerns about getting vaccinated, but will likely be much easier to convert from vaccine-hesitant to vaccine-acceptant than those who say they will “definitely not” get the vaccine or will get it “only if required” to do so. Other messages/information that are effective at persuading many in the “wait and see group” include that scientists have been working on the technology used in the new COVID-19 vaccines for 20 years; that more than 100,000 people from diverse backgrounds took part in the vaccine trials; that the vast majority of doctors who have been offered the vaccine have taken it; and that there is no cost to get the vaccine.

- Separate from concerns about the effects of the vaccine itself, about six in ten of those who are not yet convinced to get the vaccine right away are concerned that they might be required to get the vaccine even if they don’t want to.

Information and misinformation

- Reaching people with information about how to access vaccines is an ongoing challenge. As of March, many people say they still don’t have enough information about when (46%) and where (33%) they’ll be able to get the vaccine, and three in ten are not sure if they are currently eligible in their state (rising to four in ten among Hispanics, young adults, and those with lower incomes).

- Many are unaware of some basic facts about the vaccines and how they work. As of January, 34% of all those who had not been vaccinated had heard and believed or were unsure about several common “myths” about the vaccine (that it contains the live virus that causes COVID-19, that it causes infertility, or that one must pay out-of-pocket to get vaccinated), rising to 41% among the “wait and see” group and 53% among those who say they will “definitely not” get vaccinated. Around four in ten of those who are not yet convinced to get the vaccine right away (rising to half among Black and Hispanic adults) are concerned that they might get COVID-19 from the vaccine.

- Health care providers are the top source people say they will turn to for information when making decisions about whether to get vaccinated (79%, far outranking other sources in January). However, just one-quarter of those who had not yet been vaccinated said they have asked a provider about the vaccine as of February. Regardless of the sources they trust or say they will turn to, the media is a more prominent source where people are actually getting information. Asked where they have gotten information about the vaccine in recent weeks, cable (43%), network (41%), and local TV news (40%) are top sources, along with family and friends (40%). However, social media, most notably Facebook, is among the most prominent sources of information for those who want to “wait and see” about the vaccine (37%) as well as those who say they “definitely won’t” get vaccinated (40%).

Vaccine access and experiences

- While most of those who were vaccinated as of February say they were able to find or schedule a vaccine appointment on their own, about four in ten say someone else helped them, including larger shares of those with lower incomes and without college degrees. Among those who believe they are eligible but had not yet been vaccinated as of March, about a third have tried to schedule a vaccination appointment including 16% who did so successfully and 17% who say they tried but were unable to make an appointment.

- Making access to vaccines more convenient may improve uptake among some groups. Among the “wait and see” group, half say they’d be more likely to get vaccinated if their doctor offered it during a routine appointment, and four in ten of those with jobs say they’d be more likely to get it if their employer arranged for them to get vaccinated at work. Employer incentives could also play a role (38% of the employed “wait and see” say they’ be more likely to get vaccinated if their employer paid them $200), as could airline travel requirements (almost half in both the “wait and see” and “only if required” groups say they’d be more likely to get vaccinated if it was required to fly).

Challenges and opportunities for key subgroups

Despite the demographic differences in vaccination intentions noted above, no group is monolithic in their attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccines. In each demographic group, there are many who are eager to get the vaccine right away and some who say they won’t get it under any circumstances. Importantly, across all the groups we’ve analyzed, a large majority is at least somewhat open to getting the vaccine and no more than one-third say they will “definitely not” get it. Still, our in-depth survey work has revealed some insights that may be helpful for those looking to understand vaccine attitudes and increase confidence in specific populations, and those are outlined in the sections below.

Black and Hispanic adults

- Concern about getting sick with COVID-19 is high among Black and Hispanic adults who want to wait and see before getting vaccinated, but concern about experiencing serious side effects of the vaccine is also high. Given this, messages focused on protecting individuals and families from illness, while also acknowledging and/or addressing concerns about serious side effects may be most successful.

- People express a range of other concerns about the vaccine that can be addressed with better access to information and policies that make it easier for people to get the vaccine from trusted places, and many of these concerns are expressed at higher rates among people of color. In particular, among those who are not convinced to get the vaccine as soon as possible, at least half of Black and Hispanic adults are concerned that they might get COVID from the vaccine or that they might have to miss work if they have side effects. Addressing these misperceptions in conversations and outreach may be helpful.

- For Black adults in particular, reluctance to get vaccinated may be related to mistrust of the health care system that reflects both historical mistreatment and personal experiences with racism and discrimination. In fact, 38% of Black adults and 27% of Hispanic adults who are not yet convinced to get the vaccine are worried they won’t be able to get it from a place they trust.

- Black and Hispanic adults say they will turn to a wide range of information sources when making vaccine-related decisions, including individual health care providers, pharmacists, friends and family, and government health agencies. While religious leaders rank lower on the list of overall sources of information, among those who want to “wait and see,” Black adults (35%) and Hispanic adults (28%) are more likely than white adults (14%) to say they’ll turn to them for information, indicating a possible effective messenger to reach some the Black and Hispanic communities.

Republicans

- While about a third of Republicans say they will “definitely not” get the vaccine or will get it “only if required,” another 19% are in “wait and see” mode and may be receptive to messages and information aimed at increasing vaccine uptake. However, even within the “wait and see” group, partisan differences emerge that suggest different messaging strategies will be required. For example, two-thirds (67%) of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents in the “wait and see” group view vaccination as a personal choice, and half (51%) believe the seriousness of COVID-19 is being exaggerated in the news, according to the January Monitor. This suggests that messages focused on helping people make the right choice to protect their own health are more likely to resonate with Republican audiences than those that emphasize the seriousness of the pandemic or the need to get vaccinated for the collective good.

- Government sources of information (including the CDC and state and local health departments) are less trusted by Republicans than by Democrats in the “wait and see” group, so individual health care providers, pharmacists, and friends and family are a better conduit for messaging/information to Republicans.

- Republicans – who tend to be particularly concerned about personal liberty – are more likely to be concerned about being required to get vaccinated against their will. Among those who are not convinced to get vaccinated right away, a larger share of Republicans (71%) compared to independents (57%) and Democrats (53%) say they are concerned that they might be required to get the vaccine even if they don’t want to.

- Two-thirds (66%) of White Evangelical Protestants identify as Republicans or independents who lean toward the Republican Party, so there is a lot of overlap between their attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine and the attitudes of Republicans in general.

Rural residents

- In a large survey of over 1,000 adults living in rural areas, we found signs of strong early uptake and access to vaccines in rural areas. A slightly larger share of adults in rural areas compared to urban and suburban areas reported having received at least one dose of the vaccine (39% vs. 31%), and an additional 16% of rural residents want to get the vaccine as soon as they can. In addition, most adults living in rural areas feel their community has enough vaccination locations and vaccine supply to serve local residents. However, Black adults living in rural areas are less likely than White or Hispanic adults to say their community has adequate supply of these things.

- While one in five rural residents say they will “definitely not” get vaccinated, this is largely due to the disproportionate share of Republicans and White Evangelical Christians living in these areas. The concerns that rural residents have about the vaccine and the messages that resonate most to convince them to get vaccinated mirror the concerns and effective messages for the public at large.

The “definitely nots”

- Those who say they will “definitely not” get the vaccine (13% of the overall public) have a very different view of the overall pandemic compared to the rest of the population. For example, 75% of this group believes the seriousness of coronavirus has been exaggerated by the media (compared to 32% of the public overall), and 82% are not worried about themselves or a family member getting sick from COVID-19 (compared to 50% of the public overall).

- This group not only views the vaccine differently, but they also hold different views on other protective measures. For example, 96% of those in the “definitely not” group say getting vaccinated for COVID-19 is a personal choice rather than part of everyone’s responsibility to protect others (compared to 46% of the public overall who say this), and 65% believe that wearing a mask does not prevent the spread of coronavirus (compared with 20% of the public overall).

- This group is highly distrustful of government sources of information; 83% say they trust the U.S. government “not too much” or “not at all” to look out for the interests of people like them, and 71% say they do not trust the CDC for reliable information about COVID-19 vaccines.

- Of the messages and incentives we’ve tested to see what might make people more likely to get the vaccine, none are effective at moving more than a very small share of the “definitely not” group. For example, fewer than one in ten among this group say they’d be more likely to get vaccinated after hearing the vaccines are nearly 100% effective at preventing hospitalization and death from COVID-19 or that scientists have been working on the technology used in the vaccines for 20 years. A similarly small share say they’d be more likely to get vaccinated if airlines required it or if it was offered to them during a routine medical visit.

Frontline health care workers

- A KFF/Washington Post survey of frontline health care workers, including those who work in various functions such as treating patients, performing administrative duties, or assisting with patient’s daily activities and housekeeping, found that half (52%) of all frontline health workers reported receiving at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of early March and another one in five (19%) had scheduled or were planning to receive the vaccine. Another nearly one in five (18%) said they did not plan to get vaccinated and 12% had not made up their mind.

- As among the general public, COVID-19 vaccination intention among health care workers divides by race/ethnicity and education, as well as by work location and type of job duties. For example, while the large majority of those working in hospitals have been gotten the vaccine or intend to do so, almost half of those working in patients’ homes say they won’t get vaccinated or are undecided. And among physicians (and nurses with graduate degrees), nearly nine in ten report either already being vaccinated or plan to get a vaccine.

- Health care employers have a role to play in making sure their employees can get vaccinated. The share of health care workers who were offered a COVID-19 vaccine from their employer was much lower among those working in patients’ homes compared to those working hospitals and other settings.

- The potential side effects of the vaccine – a top concern among the public – are also a top concern for health care workers who have not yet been vaccinated; 82% say worry about possible side effects is a major factor in their decision about whether to get vaccinated.