Key Findings

- As the nation’s economy and rising prices are on the forefront of the public’s mind, the latest KFF Health Tracking Poll finds the public wants lawmakers to prioritize out-of-pocket health care costs as Congress debates current health legislative priorities. A majority of the public (61%) say limiting how much drug companies can increase the price of prescription drugs each year to not surpass the rate of inflation should be a “top priority” for Congress. Slight majorities also say capping out-of-pocket costs for insulin at $35 a month (53%) and placing a limit on out-of-pocket costs for seniors (52%) are top priorities for Congress to take action on in the coming months. Majorities across partisans say many of the health care priorities asked about are important for Congress to work on in the coming months.

- As many people move on from the COVID-19 pandemic, only about a quarter of the public say providing more funding to continue the COVID-19 pandemic response (25%) or making permanent the financial help that was part of the COVID-19 relief bill for people who buy their own insurance (21%) are top congressional health care priorities.

- Twelve years since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, a majority of the public (55%) continue to view the law favorably, but opinions towards the 2010 health reform law are still divided by partisanship. Majorities of Democrats (87%) hold favorable views of the law and many (43%) say the law has directly helped them and their families. On the other side of the political aisle, most Republicans (79%) view the law unfavorably and four in ten say the ACA has hurt them and their families.

- The No Surprises Act went into effect earlier this year and began protecting people with private health insurance from receiving surprise out-of-network medical bills when they received care from an in-network hospital. However, more than half of adults, 18-64, with private insurance say they know nothing at all about this legislation (56%), with an additional one in five (22%) saying they only know “a little.”

- With a renewed focus from the Biden administration on reforming long-term care facilities such as nursing homes that have been much in the news during the COVID pandemic, KFF polling finds majorities of adults say this country’s nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other long-term facilities are doing a “bad job” of maintaining adequate staffing levels (70%), offering affordable care (64%), or providing high-quality care to residents (54%). Views of the type of care provided by long-term facilities is even more negative among the one-fourth of adults who have a direct, recent connection with a long-term care facility. On the other hand, many (55%) say the country’s nursing homes are doing a “good job” of protecting residents and staff from COVID-19.

Economy and Inflation Are Public’s Top Concerns, Many Worry About Affording Basic Living Expenses

The latest KFF polling finds more than half of the public (55%) say inflation and rising prices is the biggest problem facing the U.S. right now, more than three times the share who say the same about any other issue included in the survey. About one in five (18%) say the Russian invasion into neighboring Ukraine is the biggest problem facing the U.S., followed by six percent each who say the same about the COVID-19 pandemic, crime, and climate change.

Inflation and rising prices is the top issue across partisans, with about half of Democrats (46%) and independents (53%) and seven in ten Republicans (70%) saying it is the biggest problem facing the U.S. About one in four Democrats (23%) say the Russian invasion into Ukraine is the biggest problem, as do 17% of independents and 14% of Republicans. One in ten Democrats also say either climate change (10%) or the COVID-19 pandemic (9%) is the country’s biggest problem, but few Republicans agree.

The economy, inflation, and rising prices are also the top issue for voters as the country begins the ramp up to the 2022 midterm elections. When asked to name in their own words the issue they think will be most important when deciding which candidate to vote for, more than one-third of voters (37%) offer responses related to the economy. A handful of other issues also mentioned by voters include climate change (4%), crime (3%), the Russian invasion into Ukraine (3%), taxes (2%), the COVID-19 pandemic (2%), gas or energy (2%), or immigration (2%).

In Their Own Words: Thinking about the 2022 congressional elections later this year, what issue do you think will be the most important?

“People need to get back to work and prices need to come down” – 57-year-old female, White non-Hispanic, Pennsylvania

“Rising price of gasoline” – 69-year-old male, White non-Hispanic, California

“The most important issue is economy and someone who can get the economy started up again” – 34-year-old male, Hispanic, New Jersey

“The war going on in Ukraine” – 71-year-old male, Black, South Carolina

“Lowering prices of gas and houses” – 24-year-old female, Hispanic, Texas

The economy is also the top voting issue across partisan voters, with three in ten Democratic voters, more than a third of independent voters (36%), and nearly half of Republican voters (48%) offering economic issues as their top voting concern. Some partisan voters offer things other than policy issues as the biggest driver of their vote, including wanting to vote their party’s candidates into office: one in ten (11%) Democratic voters say the most important thing to them is voting for Democratic candidates, while 6% of Republican voters offer voting Republican as the most important aspect of their voting decision.

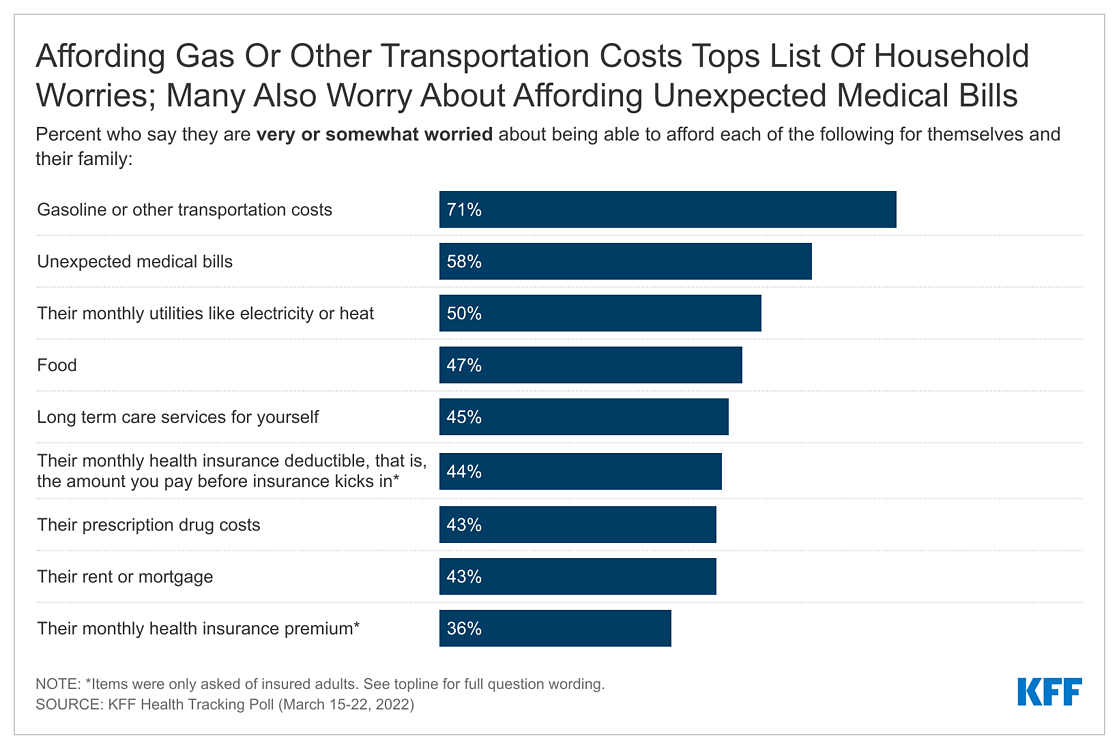

Many Americans are also concerned about being able to afford basic living expenses for their families. At least half say they are either “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about being able to afford gasoline or other transportation costs (71%), unexpected medical bills (58%), or monthly utilities like electricity (50%). At least four in ten are worried about being able to afford food (47%), long-term care services for themselves or a family member (45%), their health insurance deductible (44%), their rent or mortgage (43%), or their prescription drug costs (43%). More than one-third (36%) are also worried about being able to afford their monthly health insurance premium. The share of people who say they are now worried about affording gas prices and monthly utilities has increased since February 2020, when roughly four in ten were worried about paying for gas (40%) and monthly utilities (38%).

Worries about being able to afford living expenses are also largely dependent on an individual’s household income, with at least six in ten of those living in households with incomes of less than $40,000 annually saying they are worried about being able to afford gasoline or other transportation costs (79%), unexpected medical bills (66%), monthly utilities (65%), their rent or mortgage (63%), or their food costs (62%). However, with gas prices averaging over $4 a gallon across the country, a majority of individuals, regardless of income, report worries about being able to afford gasoline or other transportation costs.

In addition to being worried about affording health care costs along with other household expenses, half of adults (51%) report that they have delayed or gone without medical services due to costs in the past year. This includes more than one-third who have put off dental services (35%), and one-fourth who have put off vision care (25%) or general visits to their doctor or health care provider (24%). Fewer say they have put off mental health care (18%) or hospital services (14%) due to cost. One in ten say they have put off hearing services including getting hearing aids due to cost – including one in five (18%) older adults (ages 65 and older) who report this.

Lowering the price of prescription drugs has been a major tenet of President Biden’s health care agenda and a constant source of debate among legislators. The latest polling finds three in ten adults (29%), including four in ten (43%) adults with household incomes of less than $40,000, saying they have either not filled a prescription, cut pills in half or skipped doses, or taken an over-the-counter medication instead due to the cost of their prescription drugs.

The Public’s Health Care priorities For Congress Are Focused on Bringing Down Costs

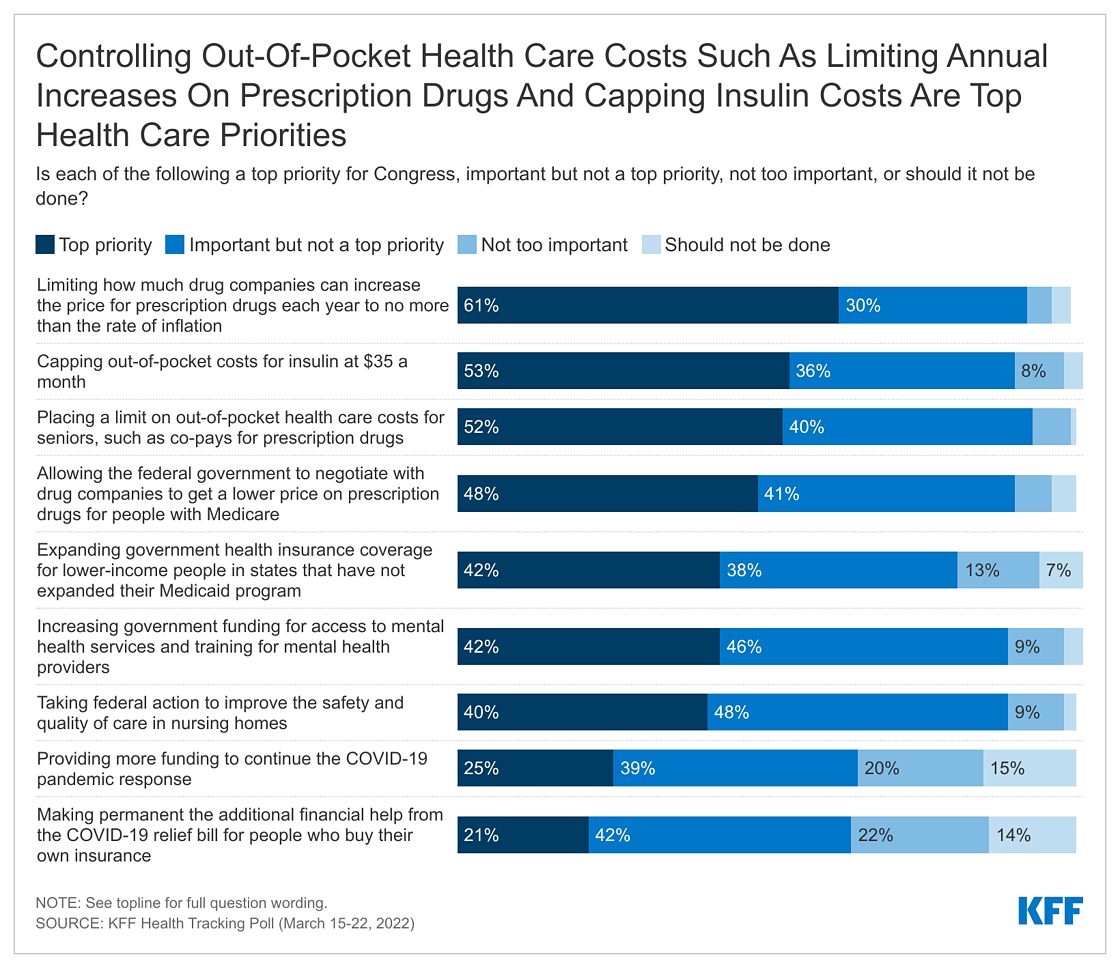

With economic issues at the forefront of the public’s mind, it is perhaps unsurprising that the top health care priorities the public wants Congress to focus on involve controlling out-of-pocket costs for families and individuals. Six in ten (61%) say limiting how much drug companies can increase the price of prescription drugs each year to not surpass the rate of inflation should be a “top priority” for Congress. Slight majorities also say capping out-of-pocket costs for insulin at $35 a month (53%) and placing a limit on out-of-pocket costs for seniors (52%) are top priorities for Congress to take action on in the coming months. About half of the public (48%) continue to say allowing the federal government to negotiate with drug companies to get a lower price on prescription drugs for people with Medicare is a top priority. Four in ten say expanding health coverage to people with lower incomes in states that have not expanded their Medicaid programs (42%), increasing government funding for access to mental health services and training for mental health providers (42%), and taking federal action to improve the safety and quality of nursing home care (40%) are top priorities for Congress. Smaller shares say providing more funding to continue the COVID-19 pandemic response (25%) or making permanent the financial help that was part of the COVID-19 relief bill for people who buy their own insurance (21%) should be top congressional health care priorities.

Across most of the health care priorities asked about, majorities – regardless of partisanship – say each is at least an “important priority” while many rise to the “top priority” more often among Democrats. Large majorities of Democrats, independents, and Republicans say limiting how much drug companies can increase the prices of prescription drugs, allowing the federal government to negotiate with drug companies to get a lower price on prescription drugs for people with Medicare, capping out-of-pocket costs for insulin at $35 a month, taking federal action to improve the safety and quality of care in nursing homes, and increasing government funding for access to mental health care are important priorities for Congress to work on in the coming months. Smaller shares of Republicans say expanding coverage for lower-income people living in non-expansion states and providing more funding for the COVID-19 pandemic response are important priorities for Congress.

Prescription drug costs

When the public are asked which party they think deserves the most blame if Congress is unable to pass legislation lowering the cost of prescription drugs, they place the blame evenly across policymakers from both sides of the aisle. About half of the public say that either President Biden (23%) or Democrats in Congress (29%) will deserve the most blame, while more than four in ten (44%) say Republicans in Congress will deserve the most blame.

The vast majority of Democrats say the blame will fall on Republicans in Congress (82%), while equal shares say the blame falls on President Biden (8%) and Democrats in Congress (8%). Among Republicans, Democrats in Congress get the majority of the blame (58%), while 29% say the blame will fall on President Biden. Four in ten independents (43%) say Republicans in Congress will deserve the most blame, while about half say Democrats in Congress (24%) or President Biden (27%) will.

Affordable Care Act and No Surprises Act

On the 12th anniversary of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the latest KFF polling finds a majority (55%) of the public continue to hold favorable views of the 2010 health reform law. This is consistent with KFF polling from last fall with no significant changes among key demographic groups. Since 2017, views of the ACA have consistently been more favorable than unfavorable, but are still largely driven by partisanship: nearly nine in ten Democrats (87%) along with six in ten independents (58%) view the law favorably, while eight in ten Republicans (79%) hold unfavorable views.

In addition, partisans hold very different perceptions of whether the ACA has directly helped or hurt them and their families. Four in ten Democrats (43%) say the ACA has “helped” them and their families, compared to one-fourth of independents (24%) and seven percent of Republicans. On the other hand, four in ten Republicans (40%) say the ACA has “hurt” them, compared to one in six independents (16%) and six percent of Democrats. At least half of all adults, regardless of self-identified party affiliation, say the ACA has had “no direct impact” on them or their family members.

About half of those who say the ACA helped them say allowing someone in their family to get or keep their health coverage has been the main way the health care law has helped them (48%, or 12% of total adults). Three in ten say the law has made it easier for them to get the health care they need (7% of total) and one in five say it has lowered the cost of their health care or health insurance (5% of total).

On the other side, more than half of those who say the ACA has hurt them believe it has increased the cost of their health care or health insurance (59%, 12% of total). This is more than twice the share who say the main way the ACA has hurt them is by making it more difficult to get the care they need (22%, 5% of total), or causing someone in their family to lose their health coverage (11%, 2% of total).

There are twelve states that have not expanded their Medicaid programs to cover more lower-income adults as part of the ACA. Among those living in non-expansion states, two-thirds (65%) say they think their state should expand Medicaid to cover more low-income uninsured people, while one-third (34%) say they think their state should keep Medicaid as it is today.

No Surprises Act

Earlier this year, a new law went into effect protecting people with private health insurance from receiving large medical bills when they accidentally received out-of-network care. Among adults, 18-64 years old, with private health insurance, about one in five say they know “a lot” (3%) or “some” (18%) about this new law. More than half say they know nothing at all about this new law (56%) while one in five say they know “a little.” Notably, partisanship does not seem to have affected awareness of the No Surprises Act with similar shares of Democrats (27%) and Republicans (22%) with private health insurance saying they knew “a lot” or “some” about the law but at least half saying they don’t know anything.

Many Are Concerned About Quality And Cost Of Care At Long-Term Care Facilities

In his State of the Union address on March 1, 2022, President Biden announced steps to improve care for residents at nursing homes, assisted living, and other long-term care facilities. The latest polling finds that nearly half of adults (45%), including 51% of adults 50 and older, worry about being able to afford long-term care services like nursing home care, and less than half rate the quality and cost of care at this country’s nursing homes positively.

Majorities of adults say this country’s nursing homes, assisted living facilities, or other long-term facilities are doing a “bad job” of maintaining adequate staffing levels (70%), offering affordable care (64%), or providing high-quality care to residents (54%). However, many (55%) say the country’s nursing homes are doing a “good job” of protecting residents and staff from COVID-19.

Views of long-term care facilities are consistent across age groups: majorities, regardless of age, say the facilities are performing poorly in maintaining adequate staffing and providing high-quality or offering affordable care. One-fourth (24%) of adults have a direct, recent connection with a long-term care facility, with them or a family member being a resident in the past three years. These individuals with a direct connection are more likely to say these facilities are doing a “bad job” at offering affordable care (70%, compared to 62% of those without a direct connection) or providing high-quality care (62% v. 51%).

In addition, nine percent of adults and six percent of older adults, ages 65 and older, say there was time in the past twelve months when they or a family member did not get long-term care because they couldn’t afford the cost.