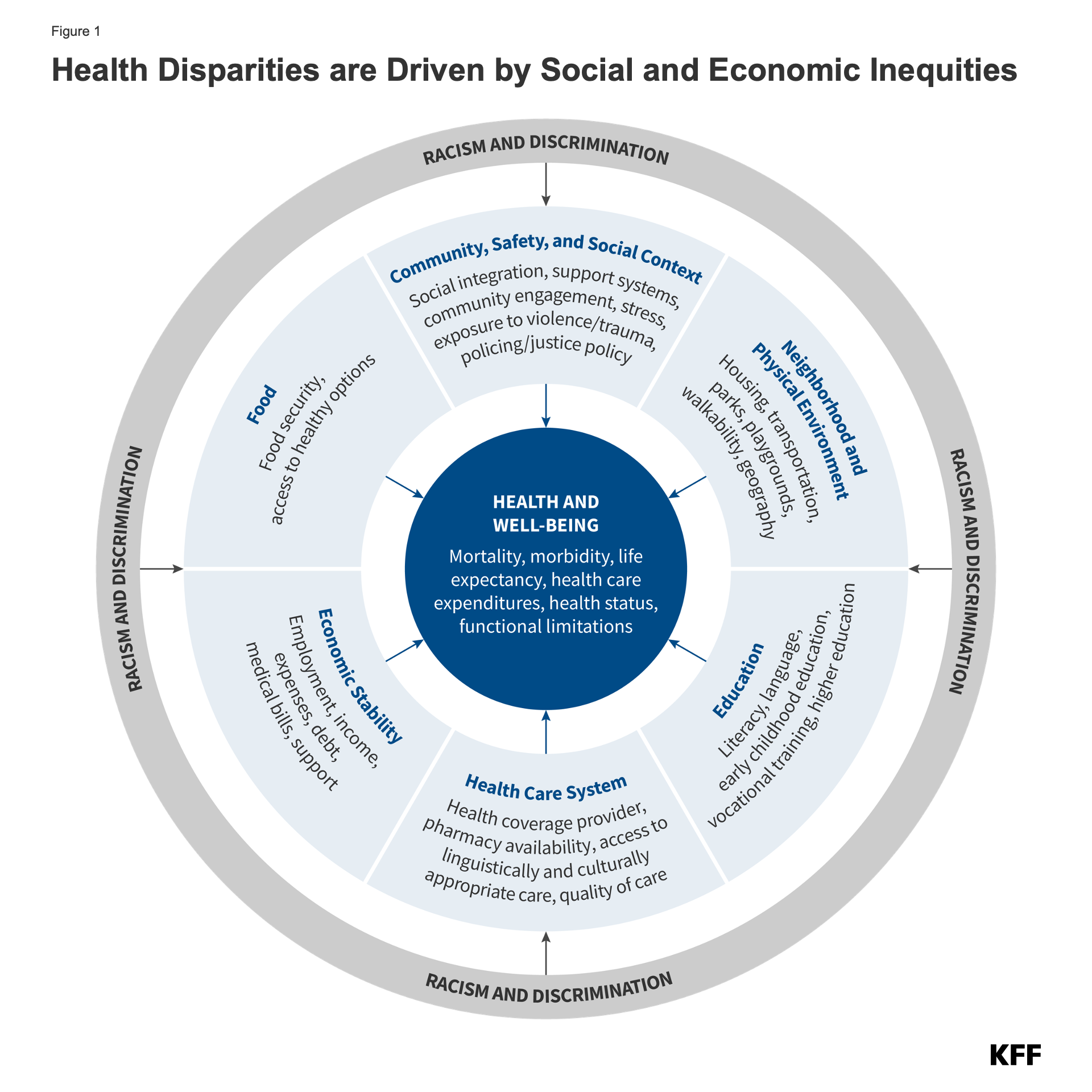

Health and health care disparities refer to preventable differences in health and health care among groups that stem from broader social and economic factors. Despite the recognition of disparities for decades and overall improvements in population health over time, many disparities persist, and in some cases, have widened over time. Disparities limit the overall health of the nation and result in unnecessary costs. This chapter provides an overview of what health and health care disparities are, the factors that drive them, the status of racial and ethnic health and health care disparities today, how recent federal actions may impact disparities, and future considerations. The information and data included in this chapter are current as of July 2025.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and racial reckoning following the murders of George Floyd and others, the federal government as well as many states and private entities increased efforts focused on addressing health disparities. Since taking office, the Trump administration has taken a range of actions to eliminate federal diversity and disparities-related initiatives, restructured and eliminated federal staff and offices that played key roles in identifying and addressing disparities, and implemented policies focused on restricting immigration and increasing interior enforcement to support mass deportation of immigrants. Moreover, the 2025 federal budget reconciliation law makes large cutbacks to federal spending for Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) provisions. These actions will likely lead to widening disparities in health and health care going forward.

Nambi Ndugga

Nambi Ndugga  Latoya Hill

Latoya Hill  Drishti Pillai

Drishti Pillai  Samantha Artiga

Samantha Artiga