The Status of Funding for Zika: Comparing the President’s Request and Congressional Proposals

Zika, a mosquito-transmitted infection that in pregnant women can cause microcephaly as well as other serious birth defects, has recently become a global challenge, and with the first cases of local transmission now reported in the U.S., a domestic one as well. No new funding for Zika has yet been appropriated by Congress. While the President requested emergency funding from Congress to address Zika last February, it has yet to approve any funding and its own proposals differ significantly from the President’s. As lawmakers return from summer recess and consider funding for the Zika virus again, a new issue brief from the Kaiser Family Foundation provides a landscape of where the debate stands and compares the President’s emergency Zika request to Congressional proposals thus far.

The brief highlights that the President’s emergency request to Congress is significantly above the amount proposed in three Congressional bills. The proposals also differ by whether the funding would be “new” appropriations or entirely offset by changes to prior appropriations, the period of time for which funds would be available, the activities supported, and restrictions on how the funding would be utilized. In all proposals, the Department of Health and Human Services would receive the majority of resources, while the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development would receive the remaining funding.

Key Implementers of U.S. Global Health Efforts

Summary

To carry out global health efforts around the world, the U.S. government (USG) funds a wide range of implementing entities, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), multilateral/international organizations, private sector organizations, educational institutions, and other governments. This brief provides an analysis of the implementing organizations that received U.S. global health funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in FY 2015. It helps to provide a more complete picture of key implementers of U.S. government global health efforts, building on earlier KFF analyses that focused on NGOs only.1 It finds that:

- In FY 2015, 773 organizations received $6.65 billion to implement global health programs in 90 countries around the world.

- Funded activities spanned all 9 major program areas of the U.S. global health portfolio, including HIV, tuberculosis, and family planning/reproductive health (FP/RH).

- Most implementing organizations were NGOs (46%), followed by private sector organizations (41%). The largest share of funding (41%) was directed to NGOs; private sector organizations received about a quarter of funding (24%). While multilateral/international organizations made up only 2% of implementing organizations, they received more than a quarter of funding (28%). Foreign governments received only a small share of funding directly (1%).

- While most implementing organizations were based outside the U.S. (55%), most funding was provided to U.S.-based organizations (62%); non-U.S.-based organizations, including local NGOs, received just 9% of funding.

- The majority of funding (56%) was provided to just 10 organizations, most of which (7) were U.S.-based; none were local NGOs.

- The greatest proportion of funding was provided to organizations working on HIV (54%), followed by maternal and child health (MCH) (13%), malaria (10%), and FP/RH (10%).

Issue Brief

Introduction

To carry out global health efforts around the world, the U.S. government (USG) funds a wide range of implementing entities, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), multilateral/international organizations, private sector organizations, educational institutions, and other governments.

This brief provides an overview of the implementing organizations that received U.S. global health funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in FY 2015.2 It is based on analysis of data on USAID spending by implementing entity.3 Such spending includes funding received by USAID directly from Congress as well as through interagency transfers (primarily from the Department of State but also from the U.S. Department of Agriculture), which together account for the majority of U.S. global health spending.4 See Appendix A for a detailed methodology.

Findings

Overview

In FY 2015, 773 organizations5 received $6.65 billion in U.S. global health funding (see Table 1) to carry out global health activities in 90 countries,6 as follows:

- Six main types of organizations received funding: NGOs,7 multilateral/international organizations, private sector organizations,8 educational institutions, foreign governments, and USG agencies and departments.

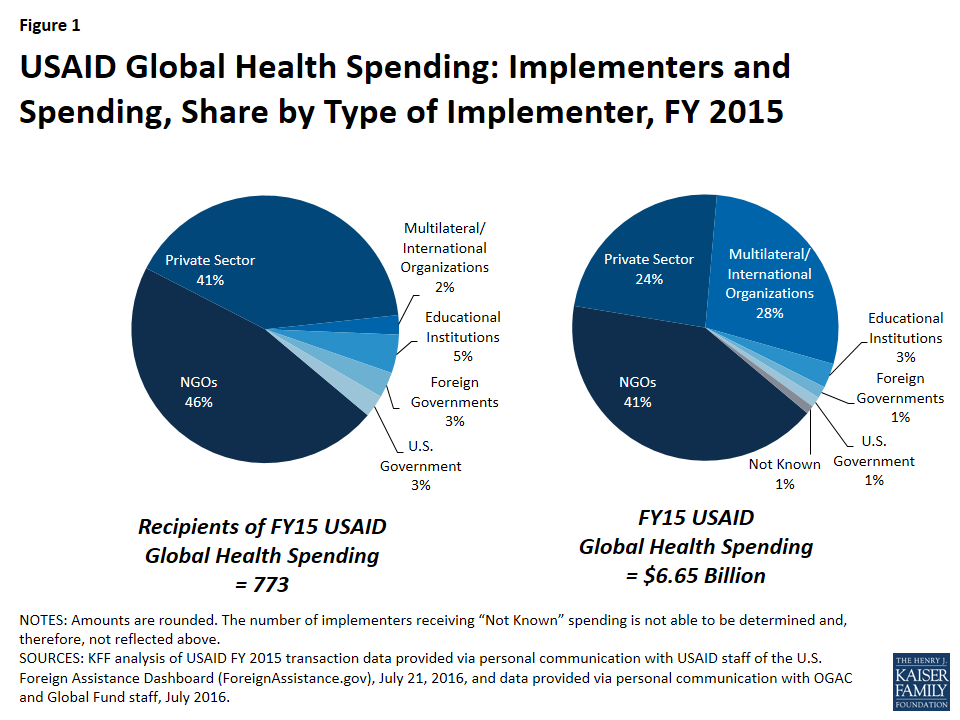

- Most implementing organizations were NGOs (46%), followed by private sector organizations (41%). Multilateral/international organizations made up only 2% of implementing organizations. See Table 1 and Figure 1.

- The largest share of U.S. global health funding went to NGOs (41%). Multilateral/international organizations received more than a quarter of funding (28%), while private sector organizations only received less than a quarter of funding (24%), followed by educational institutions (3%). Only a small share went to foreign governments (1%) or to USG agencies (1%). See Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Table 1: USAID Global Health Spending – Number of Implementers and Spending, by Type of Implementer, FY 2015 | ||

| Type of Implementer | Number of Implementers | Spending($ millions) |

| Total | 773 | 6,650 |

| NGOs | 359 | 2,760* |

| Multilateral/International Organizations | 18 | 1,864* |

| Private Sector | 315 | 1,581* |

| Educational Institutions | 36 | 197 |

| Foreign Governments | 24 | 96 |

| U.S. Government | 21+ | 84 |

| Not Known | n/a | 68 |

| NOTES: Amounts are rounded. In the data, organizations are identified by implementer type; inaccurate categorizations appearing in the data would affect the totals above. * indicates a small amount of funding was “unattributed” to an implementing organization. + indicates the number of organizations/entities reflects entities, departments, operating divisions, etc., that were individually reflected in the data. n/a indicates the number of organizations could not be accurately determined because of redacted data. | ||

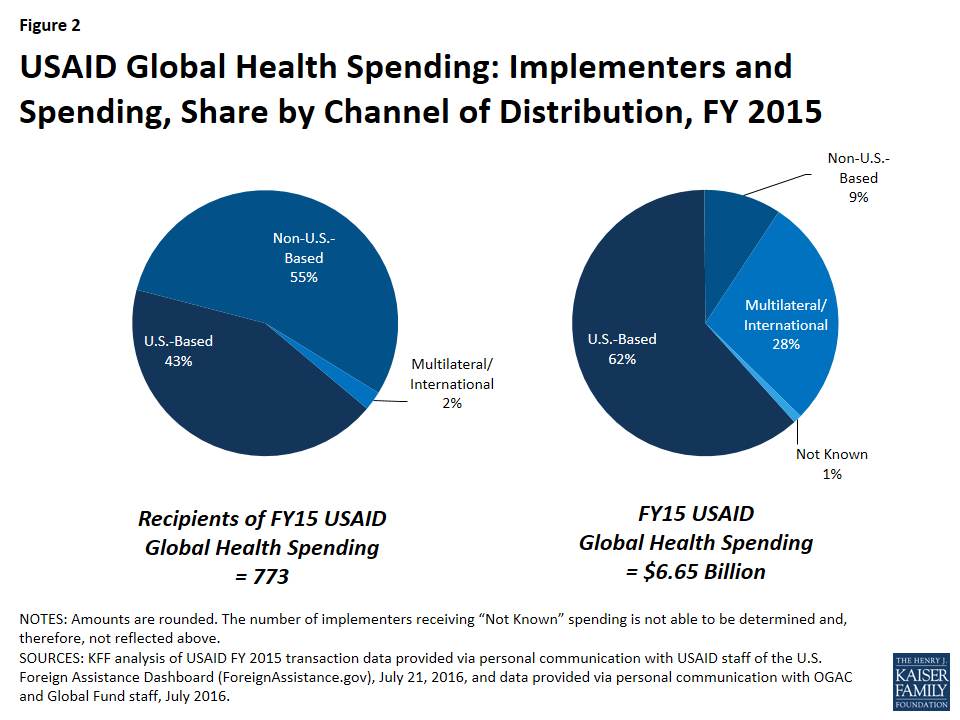

- Most implementing organizations were based outside the U.S. (55%); the rest were U.S.-based (43%) or multilateral/international organizations (2%). See Table 2 and Figure 2.

- On the other hand, most funding went to U.S.-based organizations, which accounted for $6 of every $10 (62%). The rest was provided through multilateral and international channels (28%) and to organizations that were based outside the U.S. (9%). See Table 2 and Figure 2.

| Table 2: USAID Global Health Spending – Number of Implementers and Spending, by Channel of Distribution, FY 2015 | ||

| Channel of Distribution | Number of Implementers | Spending($ millions) |

| Total | 773 | 6,650 |

| U.S.-Based | 332 | 4,093 |

| Non-U.S.-Based | 423 | 626 |

| Multilateral/International | 18 | 1,864 |

| Not Known | — | 68 |

| NOTES: Amounts are rounded. In the data, organizations are identified by implementer type and country of origin; inaccurate categorizations appearing in the data would affect the totals above. — indicates the number of organizations could not be accurately determined because of redacted data. | ||

- The majority of funding was provided to just 10 organizations (56%, $3.757 billion); of these, 3 were U.S.-based private sector organizations, 4 were U.S.-based NGOs, and 3 were multilateral/international organizations. None were local NGOs. See Table 3.

| Table 3: Top 10 Recipients of USAID Global Health Spending, FY 2015 | ||

| Implementer | Spending($ millions) | Type of Implementer |

| Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria | 1,267 | Multilateral/Int’l |

| John Snow, Inc.* | 583 | Private Sector |

| Partnership for Supply Chain Management~ | 552 | NGO |

| FHI Development 360 | 297 | NGO |

| Abt Associates | 226 | Private Sector |

| Jhpiego | 207 | NGO |

| Management Sciences for Health (MSH) | 175 | NGO |

| Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance | 175 | Multilateral/Int’l |

| Chemonics | 149 | Private Sector |

| World Bank | 124 | Multilateral/Int’l |

| NOTES: Reflects organizations that received funding spent by USAID for USG global health efforts. Amounts are rounded. Multilateral/Int’l means Multilateral/International Organization. * indicates company also has a non-profit arm that is counted separately as an NGO (JSI’s non-profit arm is JSI Research & Training Institute). ~ indicates NGO is a separate legal entity established by JSI Research & Training Institute and MSH to implement specific work. | ||

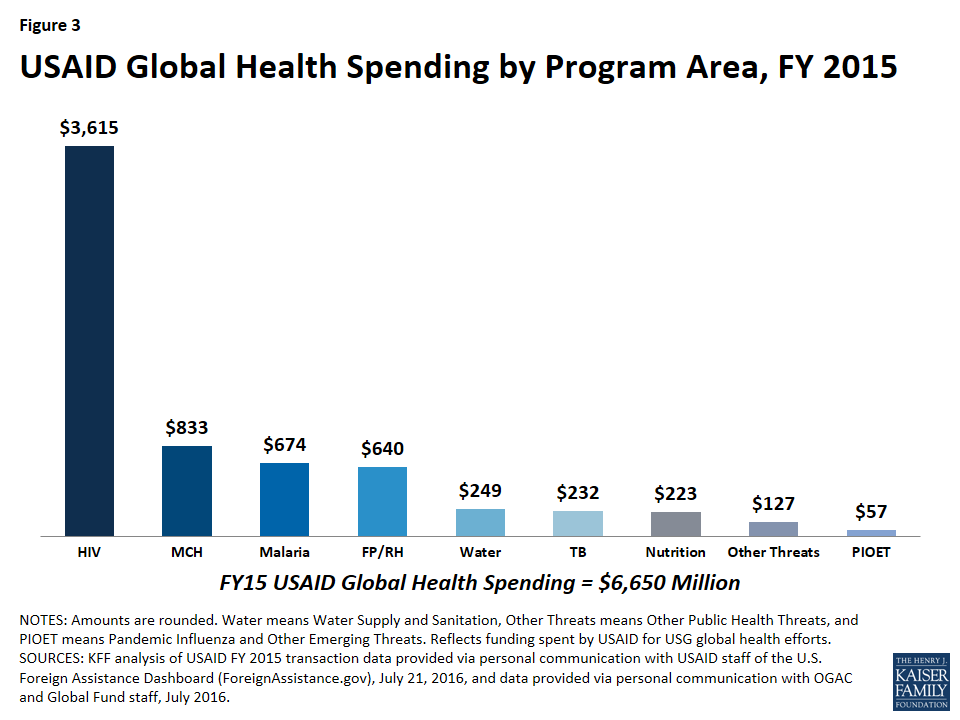

- Organizations received funding in all 9 major program areas of the U.S. global health portfolio: HIV; tuberculosis (TB); malaria; maternal and child health (MCH); nutrition; family planning/reproductive health (FP/RH); other public health threats, including neglected tropical diseases (NTDs); pandemic influenza and other emerging threats (PIOET); and water supply and sanitation. Most funding went to HIV (54%, $3.615 billion), followed by MCH (13%, $833 million) and malaria (10%, $674 million). See Figure 3.

- The major types of implementer varied by program area. For example, TB funding mostly went to NGOs (48%, $110 million), followed by multilateral/international organizations (30%, $70 million), while malaria funding mostly went to the private sector (67%, $451 million), followed by NGOs (21%, $140 million). See Table 4.

- NGOs received the most funding in five program areas (HIV, FP/RH, TB, nutrition, and other public health threats); private sector organizations received most in two program areas (malaria, and water supply and sanitation); multilateral/international organizations received most in one program area (MCH); and educational institutions received most in one program area (PIOET). See Table 4.

| Table 4: USAID Global Health Spending – Spending by Program Area, FY 2015 | ||||||||

| Program Area | Share of Spending by Type of Implementer(%) | Spending($ millions) | ||||||

| NGOs | Multilateral/International | Private Sector | Educational Institutions | Foreign Governments | U.S. Government | Not Known | ||

| HIV | 42 | 38 | 15 | 2 | <1 | 1 | 1 | 3,615 |

| MCH | 36 | 38 | 17 | 2 | 6 | <1 | <1 | 833 |

| Malaria | 21 | 5 | 67 | 3 | 1 | 3 | <1 | 674 |

| FP/RH | 48 | 3 | 39 | 5 | 3 | <1 | <1 | 640 |

| Water* | 35 | 5 | 53 | 4 | 3 | <1 | <1 | 249 |

| TB | 48 | 30 | 19 | <1 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 232 |

| Nutrition | 85 | 7 | 5 | 2 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 223 |

| Other Threats^ | 73 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | <1 | 127 |

| PIOET | 14 | 24 | 16 | 31 | <1 | 11 | 5 | 57 |

| NOTES: Percentages and $ amounts are rounded, except <1 shows those percentages under 1%. Percentages may not sum to 100%. Abbreviations mean: Multilateral/International means Multilateral/International Organizations, MCH – Maternal and Child Health, FP/RH – Family Planning and Reproductive Health, TB – Tuberculosis, PIOET – Pandemic Influenza and Other Emerging Threats. * means Water Supply and Sanitation. ^ means Other Public Health Threats, which includes NTDs. + indicates that funding for the Global Fund is attributed by USAID in the data to HIV only rather than to HIV, TB, and malaria. | ||||||||

Implementers by Type

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

As mentioned above, NGOs9 received the largest share of U.S. global health funding in FY 2015 (41%, $2.76 billion). The vast majority of this funding went to U.S.-based NGOs (85%), versus NGOs based outside the U.S. (15%). On the other hand, less than half of the NGOs who received funding were U.S.-based (41%, 148); most were based outside the U.S. (59%, 211). Additionally:

- About half (49%, $1.346 billion) of this funding went to the top 5 highest-funded NGOs, which were all U.S.-based; see Table 5.

- The majority of funding provided to NGOs was for activities related to HIV (55%), followed by FP/RH (11%) and MCH (11%); see Table 7.

| Table 5: Top 5 Recipients of USAID Global Health Spending, FY 2015 – NGOs and Multilateral/International Organizations | |

| Implementer | Spending($ millions) |

| NGOs | |

| Partnership for Supply Chain Management ~ | 552 |

| FHI Development 360 | 297 |

| Jhpiego | 207 |

| Management Sciences for Health (MSH) | 175 |

| Catholic Relief Services (CRS) | 114 |

| Multilateral/International Organizations | |

| Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria | 1,267 |

| Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance | 175 |

| World Bank | 124 |

| World Health Organization (WHO) | 107 |

| United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) | 70 |

| NOTES: Reflects organizations across selected implementer types that received funding spent by USAID for USG global health efforts. Amounts are rounded. ~ indicates NGO is a separate legal entity established by JSI Research & Training Institute and MSH to implement specific work. | |

Multilateral/International Organizations10

Nearly 20 multilateral/international organizations received more than a quarter of U.S. global health funding – the second largest share – in FY 2015 (28%, $1.864 billion). Additionally:

- The vast majority (94%, $1.743 billion) of this funding went to the top 5 highest-funded multilateral/international organizations; see Table 5. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund; an independent, international financing institution established in 2001 that provides grants to countries to address HIV, TB, and malaria)11 alone accounts for more than two-thirds of this funding (68%, $1.267 billion)12 and is the largest organizational recipient of U.S. global health funding.13

- Nearly three quarters of funding provided to multilateral/international organizations was for activities related to HIV (73%).14 See Table 7.

Private Sector

Private sector organizations received less than a quarter of U.S. global health funding in FY 2015 (24%, $1.581 billion). Nearly all funding went to U.S.-based private sector organizations (93%), versus those based outside the U.S. (7%). On the other hand, less than half of the private sector organizations that received funding were U.S.-based (44%, 139); more than half were based outside the U.S. (56%, 176). Additionally:

- Nearly three quarters (72%, $1.131 billion) of this funding went to the top 5 highest-funded private sector organizations, which were all U.S.-based; see Table 6.

- A third of funding provided to the private sector was for activities related to HIV (34%), followed by malaria (29%) and FP/RH (16%); see Table 7.

| Table 6: Top 5 Recipients of USAID Global Health Spending, FY 2015 – Private Sector, Educational Institutions, Foreign Governments, and U.S. Government Entities | |

| Implementer | Spending($ millions) |

| Private Sector | |

| John Snow, Inc.* | 583 |

| Abt Associates | 226 |

| Chemonics | 149 |

| University Research Co., LLC* | 120 |

| Futures Group International+ | 53 |

| Educational Institutions | |

| Johns Hopkins University | 75 |

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | 35 |

| Eastern Virginia Medical School | 27 |

| University of California | 14 |

| Florida International University | 9 |

| Foreign Governments | |

| Afghanistan | 46 |

| Liberia | 18 |

| Egypt | 7 |

| Pakistan | 6 |

| Tanzania | 5 |

| U.S. Government/Other Agencies | |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | 35 |

| Department of State | 8 |

| U.S. Census Bureau | 4 |

| General Services Administration (GSA) | 4 |

| Naval Medical Research Center (NMRC) | 1 |

| NOTES: Reflects organizations across selected implementer types that received funding spent by USAID for USG global health efforts. Amounts are rounded. * indicates company also has a non-profit arm that is counted separately as an NGO. For example, URC’s non-profit arm is The Center for Human Services. + indicates now known as Palladium. | |

Educational Institutions

Educational institutions received a small share of U.S. global health funding in FY 2015 (3%, $197 million). Nearly all of this funding went to U.S.-based institutions (97%), versus those based outside the U.S. (3%). Two-thirds of the educational institutions were U.S.-based (67%, 24); the rest were based outside the U.S. (33%, 12). Additionally:

- The vast majority (81%, $160 million) of this funding went to the top 5 highest-funded institutions, which were all U.S.-based; see Table 6.

- Nearly half of funding provided to educational institutions was for activities related to HIV (45%), followed by FP/RH (18%); see Table 7.

Foreign Governments

Foreign governments received a very small share of U.S. global health funding in FY 2015 (1%, $96 million). This funding went to the governments of 24 countries, which is about a quarter of the overall number of countries reached by U.S. global health funding in FY 2015. Additionally:

- Five foreign governments accounted for the vast majority (85%, $81 million) of this funding; see Table 6.

- Almost half of funding provided to foreign governments was for activities related to MCH (48%), followed by FP/RH (22%) and water (9%); see Table 7.

U.S. Government

USAID also provided approximately 1% ($84 million) of funding for global health to USG agencies:

- Five other USG agencies/departments accounted for more than half (61%, $52 million) of this funding; see Table 6. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was the largest recipient ($35 million).

- Nearly half of funding transferred to USG entities was for activities related to HIV (47%), followed by malaria (24%); see Table 7.

| Table 7: USAID Global Health Spending – Spending by Type of Implementer, FY 2015 | ||||||||||

| Type of Implementer | Share of Spending by Program Area(%) | Spending($ millions) | ||||||||

| HIV | MCH | Malaria | FP/RH | Water* | TB | Nutrition | Other Threats^ | PIOET | ||

| NGOs | 55 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 3 | <1 | 2,760 |

| Multilateral/International | 73+ | 17 | 2 | <1 | <1 | 4 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1,864 |

| Private Sector | 34 | 9 | 29 | 16 | 8 | 3 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1,581 |

| Educational Institutions | 45 | 9 | 9 | 18 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 197 |

| Foreign Governments | 7 | 48 | 8 | 22 | 9 | 2 | <1 | 3 | <1 | 96 |

| U.S. Government | 47 | 6 | 24 | 6 | 1 | 3 | <1 | 5 | 7 | 84 |

| Not Known | 78 | 5 | 3 | 6 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 2 | 4 | 68 |

| NOTES: Percentages and $ amounts are rounded, except <1 shows those percentages under 1%. Percentages may not sum to 100%. Abbreviations mean: Multilateral/International means Multilateral/International Organizations, MCH – Maternal and Child Health, FP/RH – Family Planning and Reproductive Health, TB – Tuberculosis, PIOET – Pandemic Influenza and Other Emerging Threats. * means Water Supply and Sanitation. ^ means Other Public Health Threats, which includes NTDs. + indicates that funding for the Global Fund is attributed in the data to HIV only rather than to HIV, TB, and malaria. | ||||||||||

Conclusion

To carry out its global health programs, the U.S. government funds a wide range of implementing organizations. In an effort to shed light on this landscape, this brief provides an analysis of the implementing organizations that received U.S. global health funding from USAID during FY 2015. As it finds, NGOs represent the largest group of implementers and receive the greatest share of U.S. global health funding. In addition, most implementers are based outside of the U.S. However, the analysis also finds that most funding is concentrated among a subset of implementers and is directed to U.S.-based organizations, which may have implications for longer term sustainability and country ownership. Taken together, these findings provide new information on the types of implementing organizations funded to carry out U.S. global health efforts around the world and point toward areas for further research.

Appendix

Appendix A: Detailed Methodology

This report is based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of USAID global health funding data for FY 2015, which were provided to KFF on request by USAID staff working on the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard website and by OGAC and Global Fund staff, and additional research on some of the funded organizations.

The analysis uses transaction-level data on funding disbursed by USAID to organizations for global health activities as well as the reported U.S. contribution to the Global Fund.15 Data include funding that was appropriated by Congress to USAID for global health activities and then disbursed to organizations, as well as funding that was appropriated to other agencies for global health efforts, transferred to USAID, and then disbursed to organizations.16 It does not include funding that was directly disbursed by other USG departments/agencies, such as the Department of State or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to organizations.

Funding totals are likely under-estimates, because some USAID spending has not been categorized into a specific category of activity (e.g., health, environment, economic development, etc.) in the transaction data and may include health funding.

Additionally, note:

-

Organizations were classified by implementer type based on existing categories in the data, specifically non-profit organization (referred to as NGOs in the analysis17 ), for-profit (referred to as private sector in the analysis), educational institution, government, redacted (referred to as “not known” in the analysis, and public international organization (referred to as multilateral/international organizations in the analysis). The only exception to this were entries in the “not known” type that included the name of an implementing organization: six of these organizations appeared under a specific implementer type elsewhere in the data and were re-categorized accordingly, while eight of these organizations did not appear elsewhere in the data and were re-categorized using standard conventions. Five entries that included the name of an individual (which is usually redacted in this dataset) under the “not known” type were not re-categorized and were not counted as implementing organizations.

It is possible that implementer type misclassifications by USAID are present in the data, meaning that one or more organizations may have been classified as a certain implementer type by USAID in the data when another type would have been more appropriate.

Funding totals shown in this report represent net disbursements, which include positive and negative disbursed funding amounts as well as zero-dollar disbursed funding amounts. For zero-dollar transactions, we included only transactions we could verify as no-cost extensions.18

The numbers of organizations reflected under each type were calculated based on available data, reflecting how each organization/entity appears in the data, where possible. It was not possible to calculate the number of organizations receiving funding included under the “not known” implementer type, due to redacted data on the implementing organization. Similarly, it was also not possible to precisely calculate the number of organizations receiving funding included under the non-profit organizations, private sector, and multilateral/international organizations types, due to redacted data on the implementing organization – resulting in small amounts of unattributed funding.

Funding totals in this brief should not be compared with earlier KFF analyses of USAID global health spending via NGOs, due to several differences between the datasets examined (including the availability of data on transferred funding to USAID from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which was ultimately disbursed by USAID, in the dataset used for this analysis) as well as minor differences in methodology (including NGOs and other non-profit organizations not being delineated into distinct categories in this analysis, versus the prior analyses).

Endnotes

- Figures in this analysis should not to be compared to earlier KFF analyses of USAID spending to NGOs due to data and methodology differences. See Appendix A for more information. Earlier reports include KFF: The Role of NGOs in the U.S. Global Health Response, July 2015; Foreign NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: Foreign NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, May 2015; NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: U.S.-Based NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, Dec. 2014. ↩︎

- Figures in this analysis should not to be compared to earlier KFF analyses of USAID spending to NGOs due to data and methodology differences. See Appendix A for more information. Earlier reports include KFF: The Role of NGOs in the U.S. Global Health Response, July 2015; Foreign NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: Foreign NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, May 2015; NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: U.S.-Based NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, Dec. 2014. ↩︎

- KFF analysis of USAID FY 2015 transaction data provided via personal communication with USAID staff of the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard, ForeignAssistance.gov, July 21, 2016; and KFF personal communication with OGAC and the Global Fund, July 2016. ↩︎

- Based on KFF analysis of USAID FY 2015 transaction data provided via personal communication with USAID staff of the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard, ForeignAssistance.gov, July 21, 2016; FY 2015 transaction data from the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard website, ForeignAssistance.gov, downloaded July 14, 2016; and data from the Office of Management and Budget, Agency Congressional Budget Justifications, and Congressional Appropriations Bills, and the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard website, ForeignAssistance.gov. ↩︎

- Some recipients were not identified in the data, i.e., the information was redacted, most likely for privacy reasons because the recipient was an individual. ↩︎

- Funding through U.S.- and non-U.S.-based channels directly supported activities in 90 countries; some of this funding supported “worldwide” activities and regional activities spanning five regions (Africa, Asia, Europe & Eurasia, Latin America & the Caribbean, and the Middle East) and may have reached additional countries. Additionally, funding through multilateral and international channels indirectly supported activities that may have reached additional countries/regions as well. ↩︎

- Our earlier analyses of FY 2013 and FY 2014 health spending by USAID focused specifically on NGOs and include a definition of NGOs. This category also includes other non-profit organizations, which would include those that were not identified in the data as PIOs nor, in earlier analyses, by KFF as NGOs (e.g., hospitals, educational institutions, organizations with ties to government(s), and foundations supporting these) as well as recipients that were redacted in the data but were categorized as non-profit organizations in the data. In this report, we did not categorize non-profit organizations as NGOs and other non-profits specifically and, therefore, did not delineate between them, but many of the NGOs and other non-profits identified in our earlier analyses also appear in the FY 2015 USAID health spending data. Earlier analyses demonstrated that nearly all support for non-profits went to NGOs. See KFF: The Role of NGOs in the U.S. Global Health Response, July 2015; Foreign NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: Foreign NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, May 2015; NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: U.S.-Based NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, Dec. 2014. ↩︎

- For-profit organizations. ↩︎

- This also includes other non-profit organizations, which are organizations identified in the data as non-profits that were neither identified as public international organizations in the data, nor would they classified as NGOs (see KFF definition of NGOs used in earlier analyses); they might include hospitals, educational institutions (specifically, those not classified separately as such in the data), organizations with ties to government(s), and foundations supporting these. See KFF: The Role of NGOs in the U.S. Global Health Response, July 2015; Foreign NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: Foreign NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, May 2015; NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: U.S.-Based NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, Dec. 2014. ↩︎

- Referred to in the data as Public International Organizations (PIOs), which are defined in USAID, ADS Chapter 308: Awards to Public International Organizations, April 3, 2014, as “an international organization composed principally of countries or such other organization as designated pursuant to” a section therein, and also in USAID, ADS Glossary, April 30, 2014, as “an organization in which the U.S. participates composed principally of governments.” ↩︎

- For more information on the Global Fund, see KFF, “The U.S. & The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria,” fact sheet. ↩︎

- This is the amount of funding that the U.S. government and the Global Fund reported as the U.S. contribution for FY 2015, although a portion of it was disbursed in FY 2016 due to congressional requirements on the overall level of U.S. funding for the Global Fund. KFF personal communication with OGAC and the Global Fund, July 2016. ↩︎

- This funding is provided by Congress to the Department of State, which in turn provides it as a pass-through to USAID. KFF personal communication with OGAC, March 2016; CRS, U.S. Agency for International Development: Background, Operations, and Issues, July 21, 2015, R44117. ↩︎

- Funding for the Global Fund is attributed by USAID in the data to HIV only rather than to HIV, malaria, and TB. ↩︎

- This is the amount of funding that the U.S. government and the Global Fund reported as the U.S. contribution for FY 2015, although a portion of it was disbursed in FY 2016 due to congressional requirements on the overall level of U.S. funding for the Global Fund. KFF personal communication with OGAC and the Global Fund, July 2016. ↩︎

- For example, USAID transaction data analyzed for this report include funds transferred from the Department of State to USAID for HIV efforts, which were then obligated and eventually disbursed to various implementing organizations. ↩︎

- Our earlier analyses of FY 2013 and FY 2014 health spending by USAID focused specifically on NGOs and include a definition of NGOs. Other non-profit organizations would include those that were not identified in the data as PIOs, nor would they classified as NGOs (see KFF definition of NGOs used in earlier analyses); they might include hospitals, educational institutions (specifically, those not classified separately as such in the data), organizations with ties to government(s), and foundations supporting these. See KFF: The Role of NGOs in the U.S. Global Health Response, July 2015; Foreign NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: Foreign NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, May 2015; NGO Engagement in U.S. Global Health Efforts: U.S.-Based NGOs Receiving USG Support Through USAID, Dec. 2014. ↩︎

- Positive and negative disbursements along with zero-dollar disbursements that are no-cost extensions are each closely linked to the recent completion or ongoing execution of global health activities, providing the best approximation available for showing where work is being done. ↩︎

Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: August 2016

Findings

KEY FINDINGS:

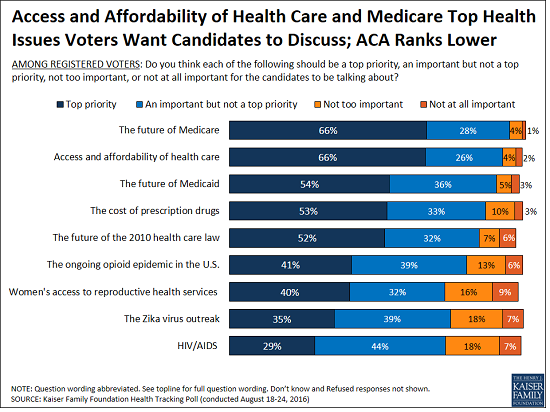

- Two-thirds of voters say the future of Medicare and access and affordability of health care are top priorities for the candidates to be talking about during the 2016 presidential campaign.

- More voters trust Hillary Clinton to do a better job dealing with health care issues than trust Donald Trump, although few believe their own ability to access affordable health care would get better regardless of which candidate is elected. Voters, age 65 and older, are split between which candidate they trust to do a better job dealing with the future of Medicare with a similar share saying they trust Trump (44 percent) as say they trust Clinton (47 percent).

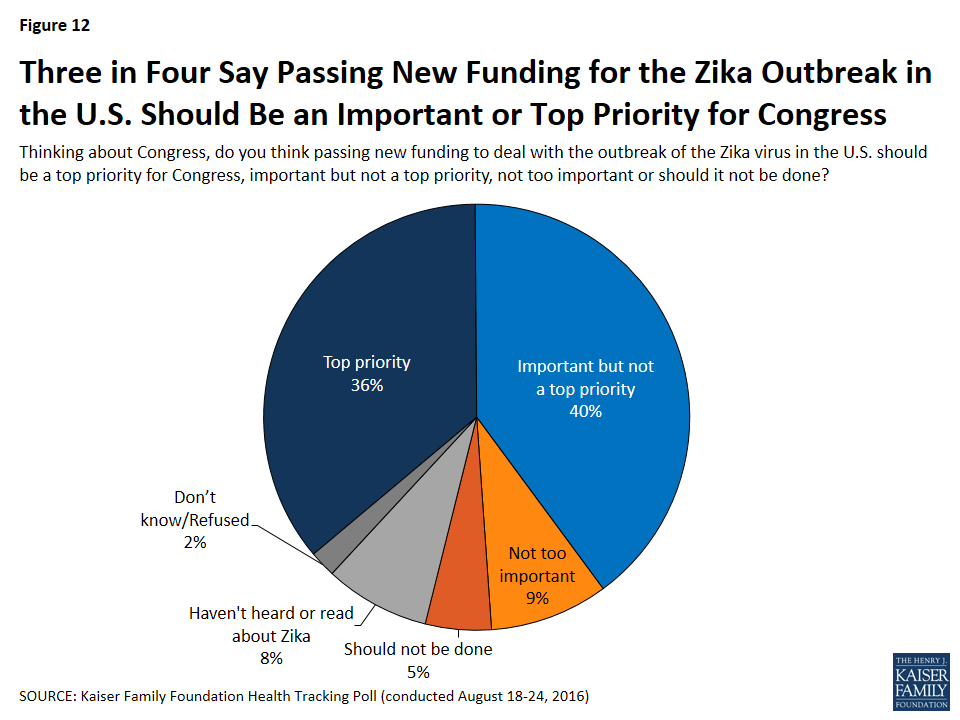

- Almost all Americans have heard or read about the Zika virus (92 percent), and one-third (36 percent) say that passing new funding to deal with the outbreak in the U.S. should be a top priority for Congress, with an additional 40 percent saying it should be an important but not a top priority. A large majority of all partisans say that new Congressional funding should be at least an important priority for Congress.

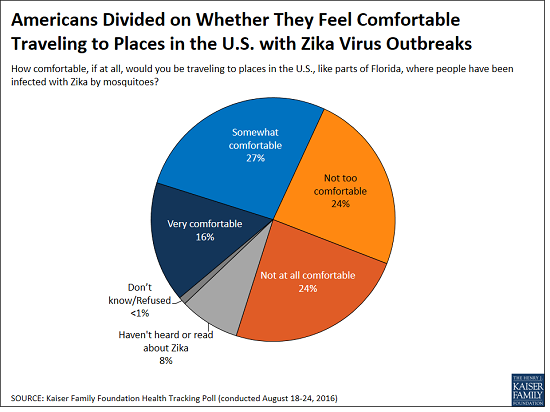

- About half of the public says they would not feel comfortable traveling to places like parts of Florida where people have been infected with the Zika virus by mosquitoes. In addition, three-fourths (77 percent) say these places are generally unsafe for pregnant women. The Kaiser Family Foundation has been tracking public opinion on Zika since February 2016; for more poll results, visit the up-to-date Zika slideshow.

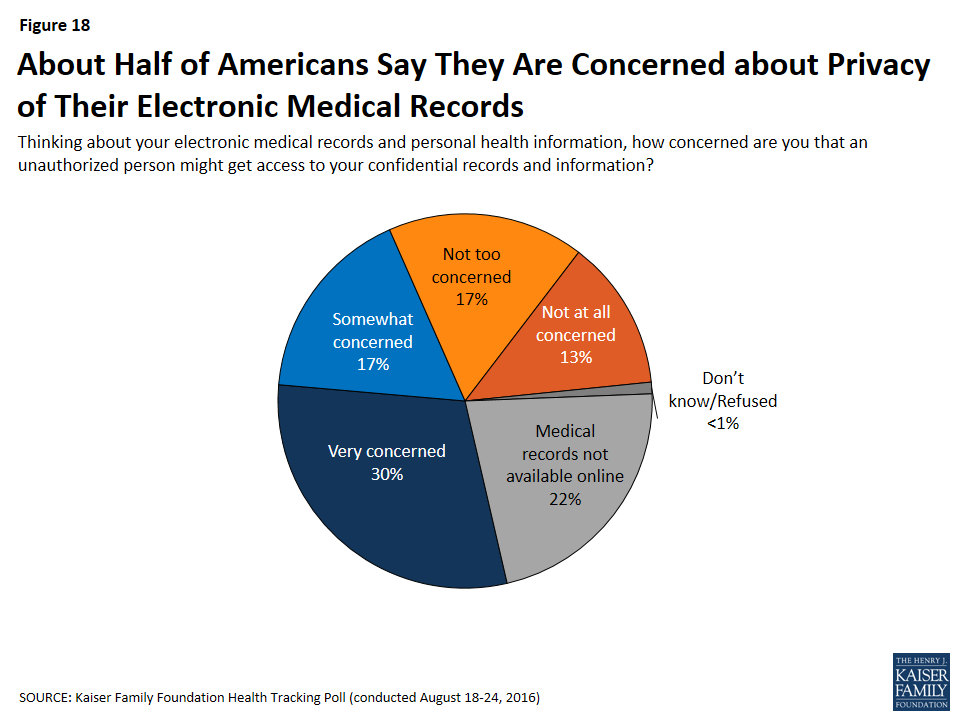

- About half of Americans are concerned that an unauthorized person might get access to their confidential records and information; despite this, 80 percent say it is important that their doctors use online medical records.

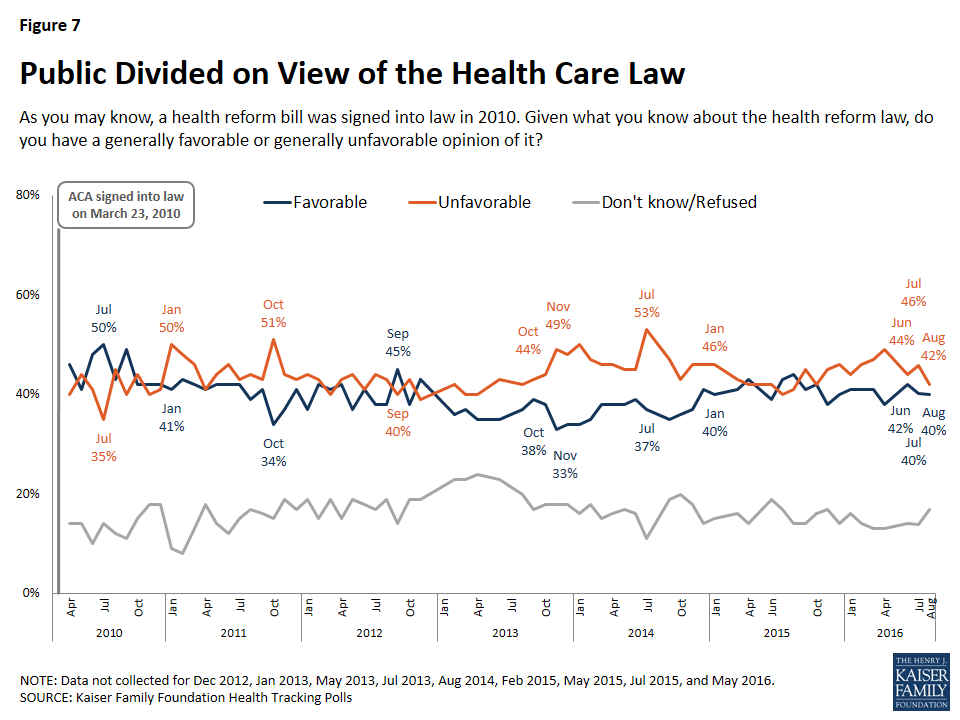

- Americans’ opinion of the health care law remains split, with 40 percent saying they have a favorable view and 42 percent saying they have an unfavorable view.

Voters and the 2016 Presidential Campaign

There are less than 10 weeks until the 2016 general election and no shortage of issues for the presidential candidates to discuss on the campaign trail and in upcoming debates. While health care has generally taken a backseat so far in the 2016 presidential election,1 during the past month, there have been several health policy stories garnering media attention including the Zika virus outbreak, prescription drug costs, health insurers leaving ACA marketplaces, and the ongoing opioid epidemic. These are in addition to other health policy issues the next president will almost certainly have to address.

When asked which health issues the presidential candidates should prioritize discussing during the 2016 presidential campaign, two-thirds of voters say the future of Medicare and access and affordability of health care are top priorities for the candidates to be talking about. About half of voters also say the future of Medicaid (54 percent), the cost of prescription drugs (53 percent), and the future of the health care law (52 percent) are top priorities. Fewer than half say the ongoing opioid epidemic (41 percent) and women’s access to reproductive health services (40 percent) are top priorities, with 35 percent saying the same about the Zika virus outbreak and 29 percent saying the same about HIV/AIDS. While the Zika virus outbreak is not viewed by the majority of voters as a top priority for candidates to discuss during the campaign, it is the most closely followed health policy news story during August.

Partisans hold differing opinions on which health issues are a “top priority” for the presidential candidates to be talking about during the presidential campaign. Three-fourths (77 percent) of Democratic voters say access and affordability of health care is a top priority; however, this opinion is shared by a smaller majority of independent voters (62 percent) and Republican voters (55 percent). Six in ten Republican voters say the future of Medicare is a top priority for the candidates to be talking about, which is equal to the share of independent voters who say the same, and lower than the share of Democratic voters (73 percent) who say the same.

A smaller share of Republican voters than Democratic voters say that each health issue should be a top priority for the presidential candidates to discuss during the presidential campaign, with one notable exception — the future of the 2010 health care law. Similar shares of Republican voters (55 percent) and Democratic voters (59 percent) say the health care law should be a top priority for the candidates to be talking about, compared to a smaller share (44 percent) of independent voters.

| Table 1: Top Health Priorities for the Candidates to Discuss During the 2016 Presidential Election | ||||

| The percent who said the following should be a “top priority” for the presidential candidates to be talking about during the 2016 presidential campaign | All Registered Voters | RepublicanVoters | DemocraticVoters | IndependentVoters |

| Access and affordability of health care | 66% | 55% | 77% | 62% |

| The future of Medicare | 66 | 60 | 73 | 60 |

| The future of Medicaid | 54 | 43 | 64 | 50 |

| The cost of prescription drugs | 53 | 47 | 63 | 48 |

| The future of the 2010 health care law | 52 | 55 | 59 | 44 |

| The ongoing heroin and prescription painkiller addiction epidemic in the U.S. | 41 | 34 | 51 | 35 |

| Women’s access to reproductive health services | 40 | 21 | 59 | 37 |

| The Zika virus outbreak | 35 | 30 | 44 | 30 |

| HIV/AIDS | 29 | 18 | 38 | 28 |

Who Do the Voters Trust On Health Issues?

When it comes to dealing with health issues facing the country, a larger share of voters say they trust Hillary Clinton to do a better job than say they trust Donald Trump to a better job. In fact, across all of the health issues included in this survey, at least half of voters say they trust Clinton to do a better job, and on the majority of the health issues, she has a double digit percentage point advantage over Trump. The largest difference between the two presidential candidates is on women’s access to reproductive health services; 64 percent of voters say they trust Clinton to do a better job dealing with this compared to 28 percent of voters who say they trust Trump to do a better job, giving Clinton a 36 percentage point advantage. A majority of female voters (71 percent) say they trust Clinton to do a better job on women’s access to reproductive health services compared to one in five (20 percent) who say they trust Trump. The smallest difference is on the future of the 2010 health care law, on which Clinton has a 9 percentage point advantage over Trump (50 percent compared to 41 percent). Voters, age 65 and older, are split between which candidate they trust to do a better job dealing with the future of Medicare with a similar share saying they trust Trump (44 percent) as say they trust Clinton (47 percent).

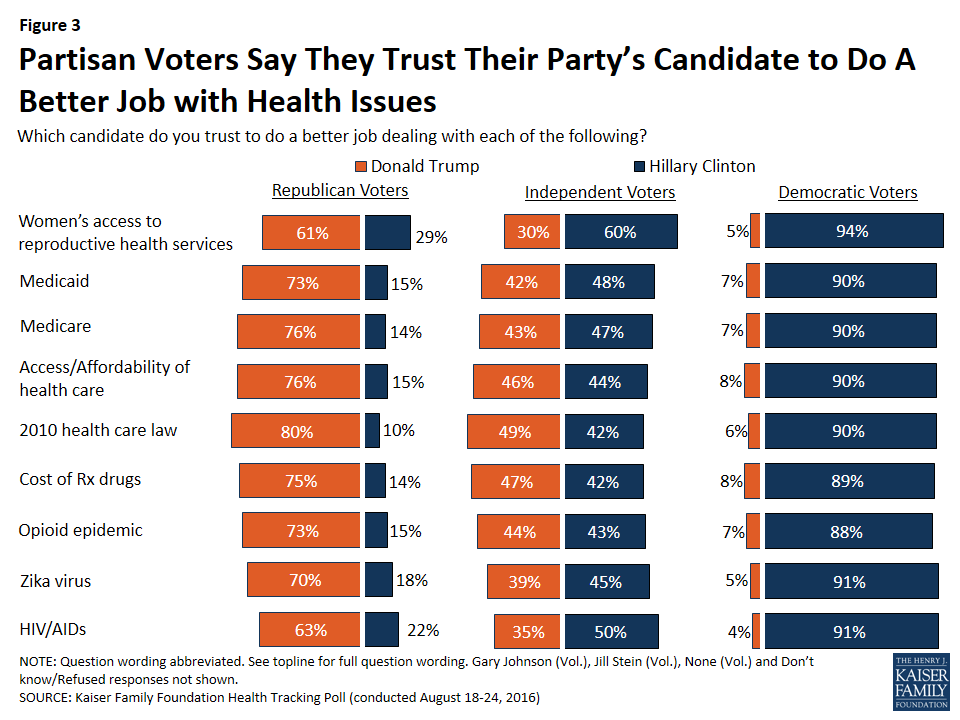

Majorities of voters from each political party say they trust their party’s candidate to do a better job dealing with each of the health issues compared to the other party’s candidate. Across all health issues, about nine out of ten Democratic voters say they trust Clinton to do a better job while a smaller share, yet still a majority, of Republican voters say they trust Trump to do a better job. Independent voters are more divided on all of these health care issues.

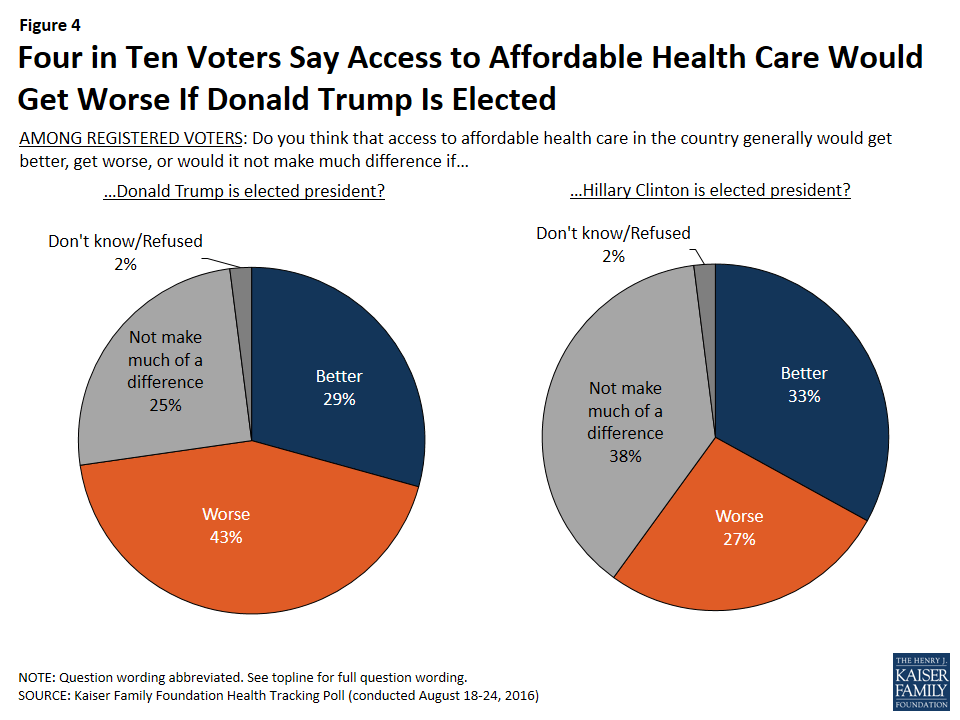

Access and Affordability of Health Care

When asked about how access to affordable health care in the country would change if Trump were elected, four in ten voters (43 percent) say that it would get worse, three in ten (29 percent) say it would get better, and one-fourth say it would not make much of a difference. When asked the same about if Clinton were elected president, 27 percent of voters say access to affordable health care in the country generally would get worse, one-third say it would get better, and four in ten (38 percent) say it would not make much of a difference.

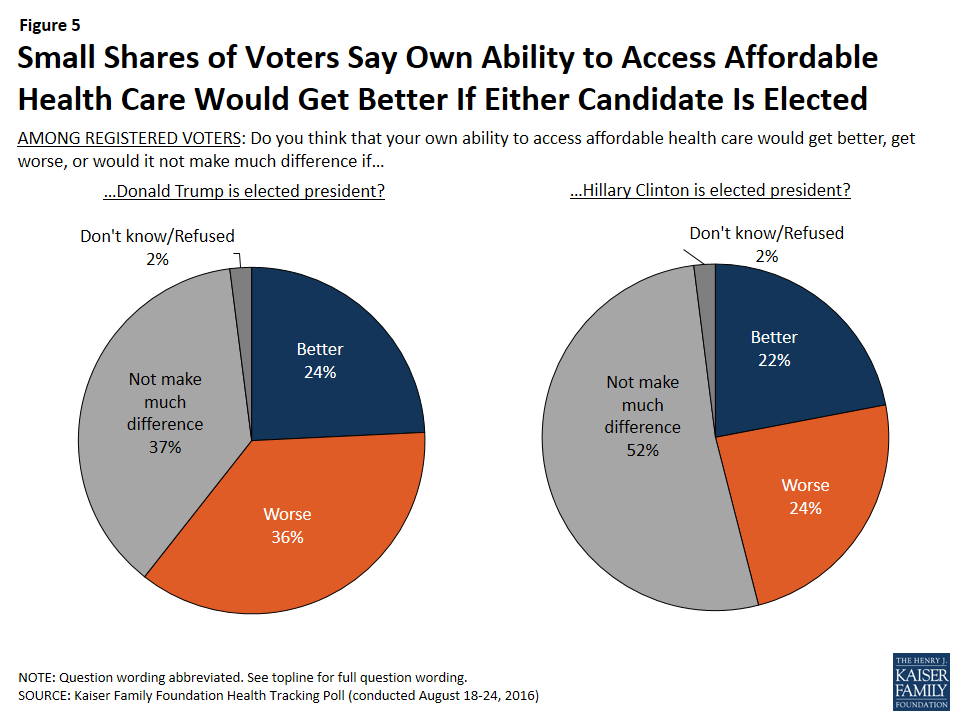

When asked how a Trump or Clinton presidency would affect their own ability to access affordable health care, half of voters (52 percent) say if Clinton is elected president it would not make much of a difference, while similar shares say it would get better (22 percent) as say it would get worse (24 percent). This is compared to 37 percent of voters who say that if Trump is elected, it would not make much of a difference in their own ability to access affordable health care, 36 percent who say it would make their own ability to access affordable health care get worse, and 24 percent who say it would get better.

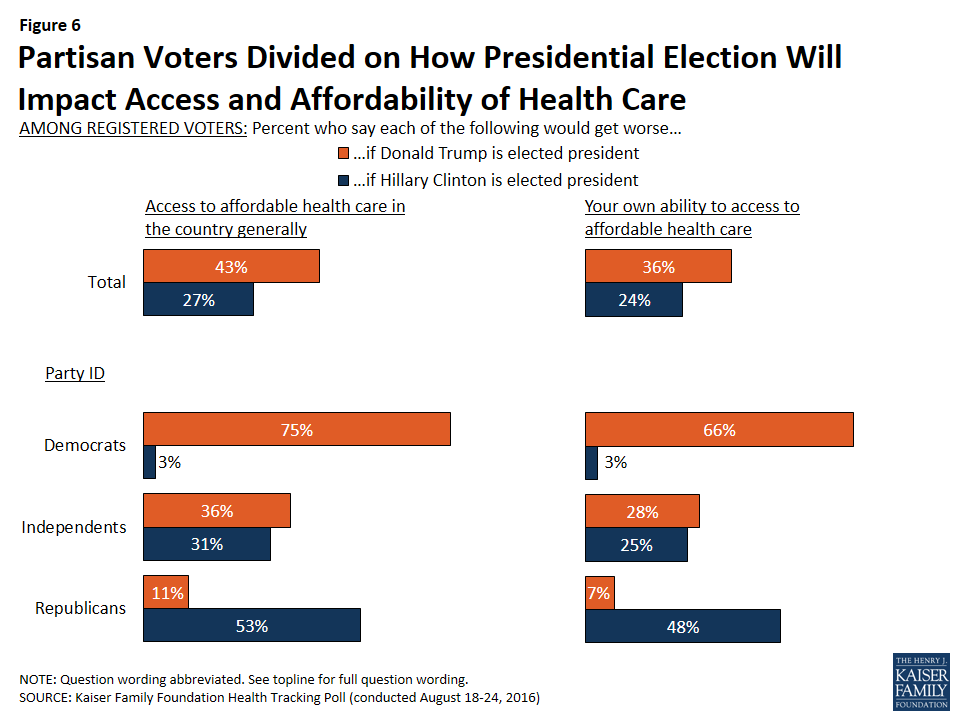

Partisan voters are divided on how access to affordable health care would change, both in the country generally and for them personally, under a Trump or Clinton presidency. Three-fourths of Democratic voters say that if Donald Trump were elected president, access to affordable health care in the country generally would get worse (compared to 11 percent of Republican voters); two-thirds of Democratic voters say their own ability to access affordable health care would get worse if Trump were elected (compared to 7 percent of Republican voters). On the other hand, if Hillary Clinton were elected president, 53 percent of Republican voters say access to affordable health care in the country generally would get worse (compared to 3 percent of Democratic voters), and 48 percent say their own ability to access affordable health care would get worse (compared to 3 percent of Democratic voters). Independent voters are split on what would happen if Trump or Clinton is elected, with about one-fourth saying their own ability to access affordable health care would get worse if either candidate was elected.

Americans’ Opinions of the Affordable Care Act

Americans’ opinion of the health care law remains divided, with 40 percent saying they have a favorable view and 42 percent saying they have an unfavorable view.

Furthermore, partisans continue to hold widely differing views; two-thirds of Democrats (67 percent) report a favorable view, while three-fourths of Republicans (76 percent) report an unfavorable view and independents tilt negative, with 37 percent saying they have a favorable opinion and 47 percent saying they have an unfavorable opinion.

When asked about the news media’s coverage of the health reform law, four in ten say that the coverage is mostly balanced while 27 percent say it is biased in favor of the law and 21 percent say it is biased against the law. About half (47 percent) of Republicans say the news media coverage of the health reform law is biased in favor of the law while half of Democrats and 43 percent of independents say the news coverage is mostly balanced.

The Zika Virus Outbreak

The Zika virus outbreak continues to be the health policy story most followed by Americans. In July, health officials confirmed the first cases of individuals being infected by mosquitoes in the U.S. in a Miami, Florida neighborhood, and a subsequent travel advisory recommended that pregnant women stay away from the area.2

The August tracking poll takes a look at the public’s knowledge of these recent developments, their attitudes about travel to – and safety of – areas affected by Zika, and their views on the importance of Congressional funding to deal with the outbreak in the United States. The Kaiser Family Foundation has been tracking public opinion on Zika since February 2016; for more poll results, visit the up-to-date Zika slideshow.

Knowledge of Local Transmission and Domestic Travel Warnings

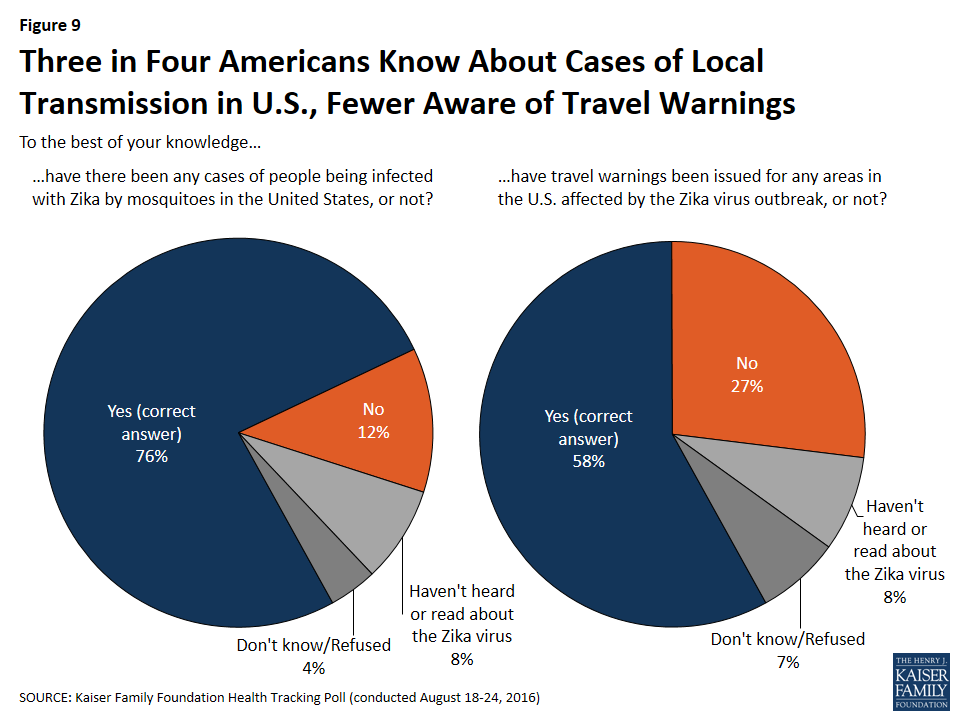

Three-fourths of the public (76 percent) are aware that there are cases of local transmission in the country – that is, cases where people are being infected with the Zika virus by mosquitoes. A smaller share, but still a majority, report being aware of travel warnings issued for areas in the United States affected by the outbreak (58 percent).

Attitudes Toward Traveling to Places Affected by Zika

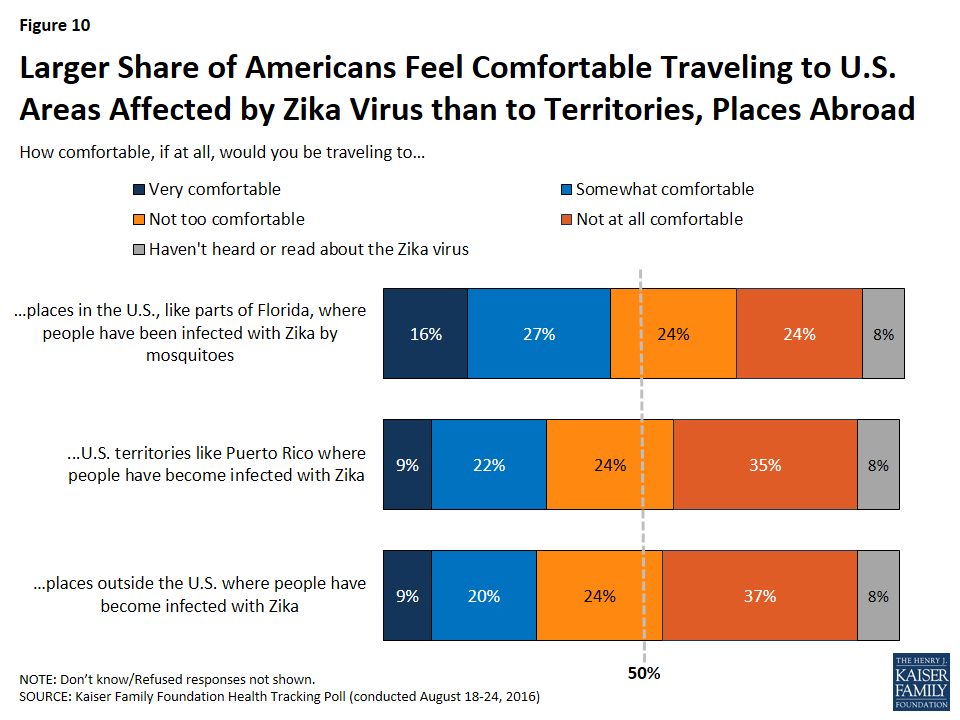

About half of the public (48 percent) say that they would be “not too” or “not at all” comfortable traveling to places in the U.S., like parts of Florida, where people have been infected with Zika by mosquitoes. In contrast, six in ten say they would be not be comfortable traveling to U.S. territories like Puerto Rice where people have become infected (59 percent) or to places outside the U.S. where people have become infected (61 percent).

Individuals who report being aware of travel warnings for areas in the U.S. affected by Zika are more likely to say they are not comfortable traveling to places affected by the virus. For example, when asked about traveling to places in the U.S. like Florida where people have been infected by mosquitoes, 59 percent of individuals aware of travel warnings say that they would not be comfortable, compared to 39 percent of those who thought travel warnings had not been issued. In addition, women are not as comfortable traveling to places affected by Zika than men. Fifty-three percent of women, compared to 43 percent of men, report being not comfortable traveling to places in the U.S. where people have been infected by mosquitoes.

Evaluations of Safety for Pregnant Women

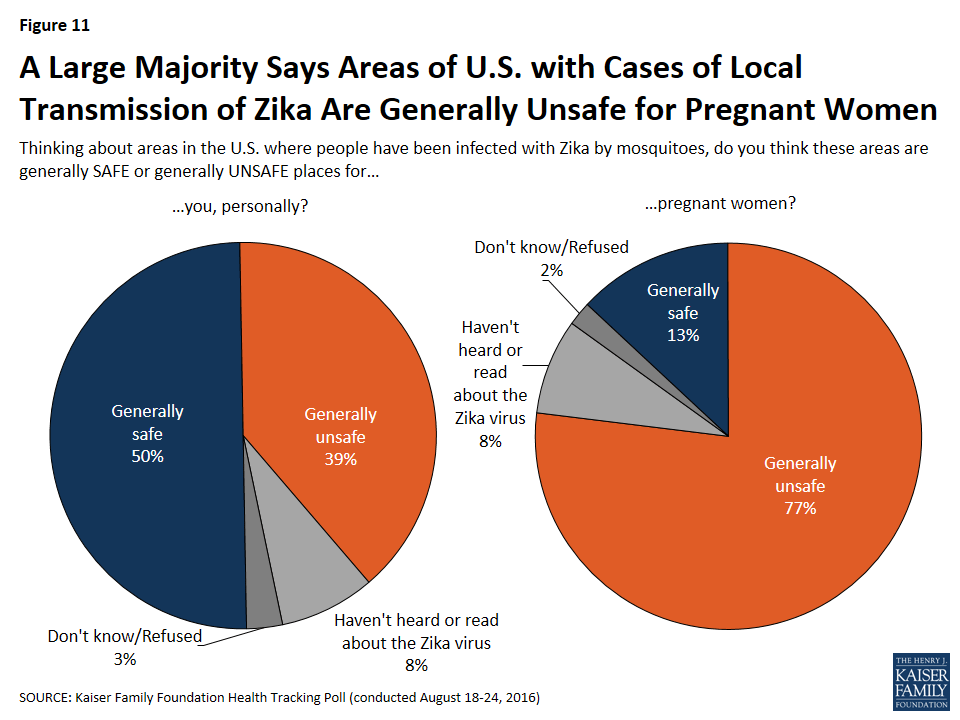

A large majority – 77 percent – of the public say they think areas in the U.S. where people have been infected by mosquitoes are generally unsafe for pregnant women. A small share appears concerned about the safety of these places for themselves, with half saying that areas in the U.S. where people have been infected with Zika by mosquitoes are generally safe for them, personally and 39 percent saying they are generally unsafe.

Individuals aware of the travel warnings issued for places in the U.S. affected by Zika are more likely to say that places with local transmission are generally unsafe for pregnant women (89 percent v. 77 percent of those who thought travel warnings had not been issued). They are also more likely to say that such places are generally unsafe for them, personally (47 percent v. 32 percent). Furthermore, women are more likely than men to say that places with local transmission are generally unsafe for pregnant women (81 percent v. 74 percent) and to say they are generally unsafe for themselves, personally (43 percent v. 35 percent).

Most See Congressional Funding to Deal with the Virus as an Important Priority

Despite President Obama’s February request for almost $1.9 billion to deal with the Zika virus outbreak,3 U.S. Congress has not passed any additional funding. Thirty-six percent of the public say that passing new funding to deal with the outbreak in the U.S. should be a top priority, with an additional 40 percent saying it should be an important but not a top priority. Nine percent think passing new funding is not too important, and 5 percent say that new funding should not be passed at all.

There are partisan differences in these findings, with a larger share of Democrats than independents or Republicans saying Congressional funding to deal with the Zika virus outbreak should be a top priority (46 percent v. 34 percent and 27 percent). However, a large majority of all partisans say that new Congressional funding should be at least an important priority of Congress.

| Table 2: Majorities of Democrats, Independents, and Republicans Say New Funding to Deal with Zikafrom Congress Should at Least Be an Important Priority | ||||

| Percent who say new Congressional funding to deal with the Zika virusoutbreak in the U.S. should… | Total | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| Be a top priority | 36% | 46% | 34% | 27% |

| Be an important but not top priority | 40 | 36 | 41 | 46 |

| Be not too important | 9 | 6 | 12 | 10 |

| Not be done | 5 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

Electronic Health Records

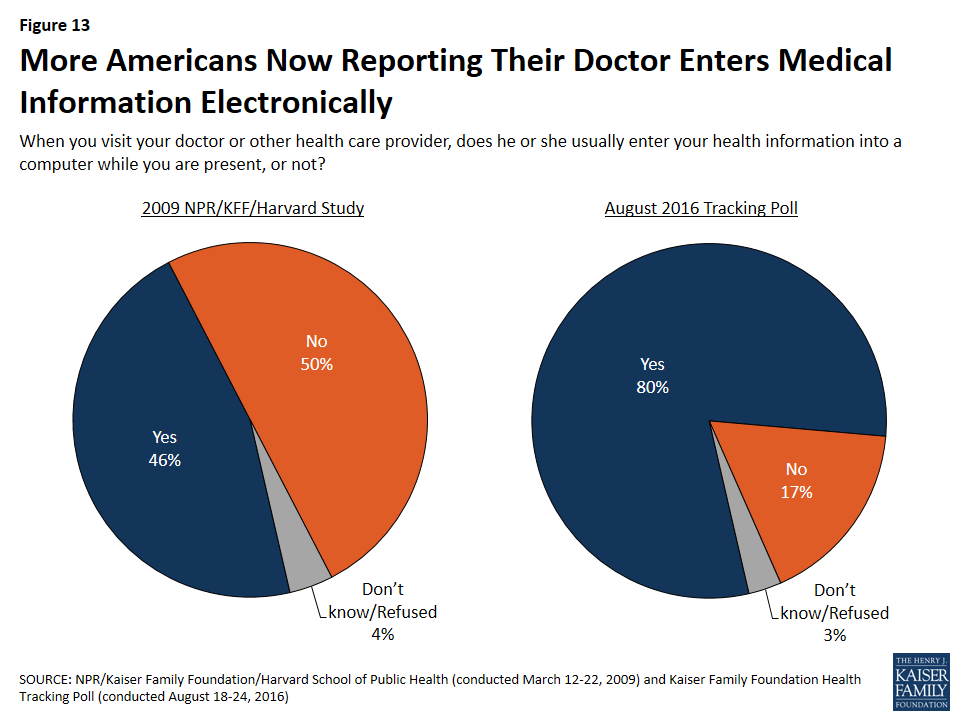

In 2009, the federal government passed the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act which allocated $27 billion for an incentive program encouraging health care providers to adopt electronic health records systems (EHR).4 In a 2009 poll5 conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation, NPR, and the Harvard School of Public Health, about half of the public (46 percent) reported that their doctor entered their health information into a computer during a visit. In the most recent survey, eight in ten Americans say their doctor or health care provider enters their health information into a computer during a visit.

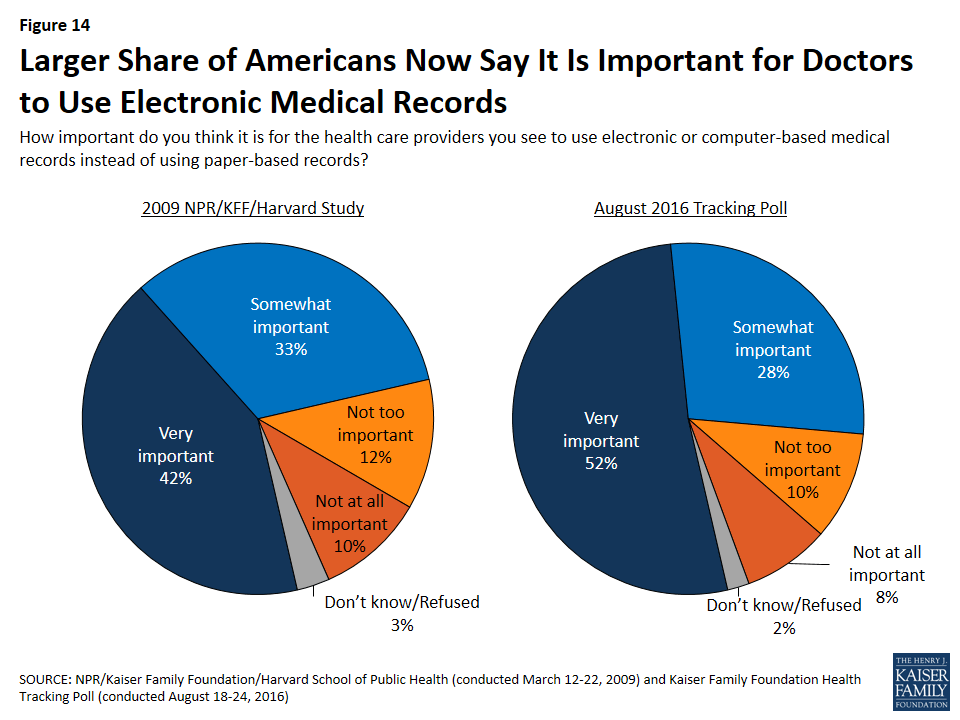

In addition, half (52 percent) of Americans say it is “very important” for their health care provider to use electronic or computer-based medical records instead of using paper-based records, up from 42 percent in 2009.

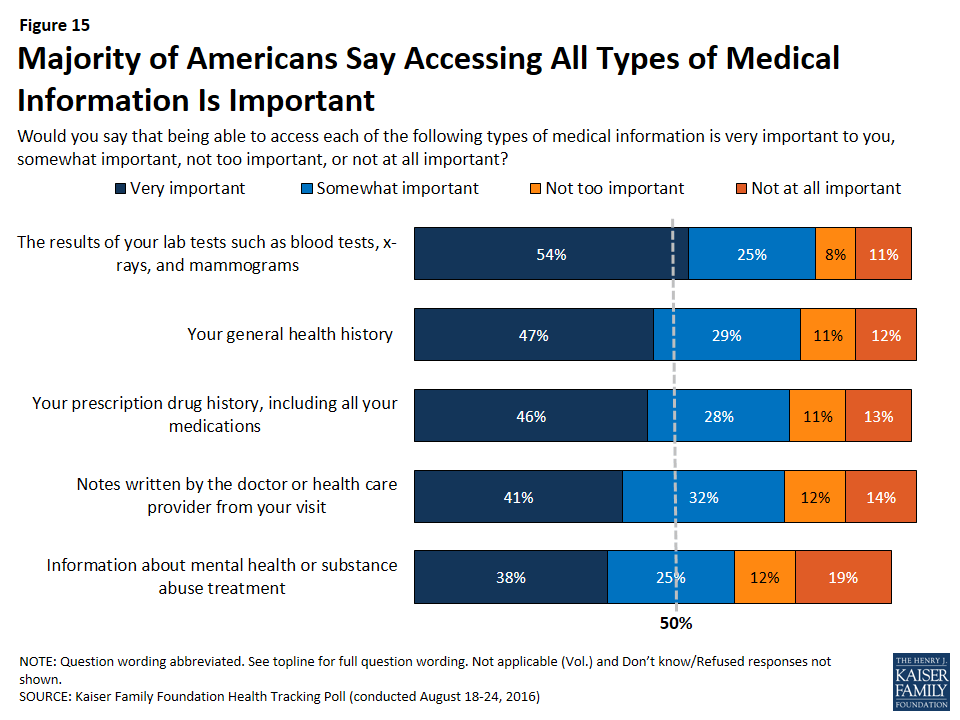

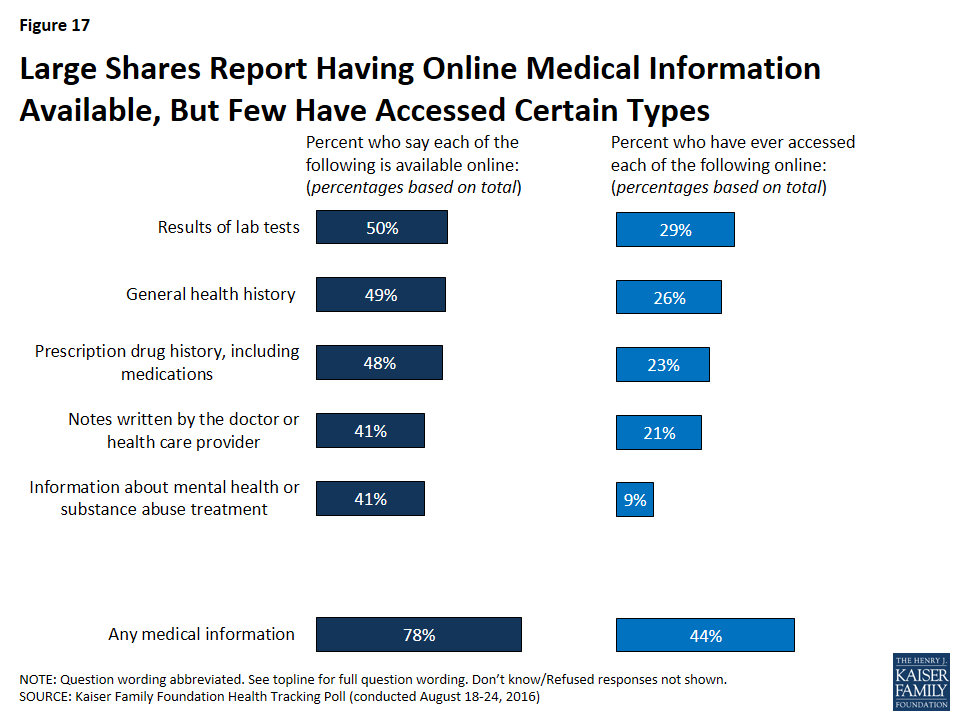

When asked about what type of medical information is important to be able to access, the majority of the public say each type of information included in the survey is at least “somewhat” important. Eight in ten (79 percent) say being able to access the results of their lab tests is at least somewhat important. This is followed by about three-fourths who say the same about being able to access their general health history (75 percent), their prescription drug history (74 percent), and the notes written by their doctor of health care provider from their visit (73 percent). A smaller share (63 percent) say accessing information about their mental health or substance abuse treatment is at least somewhat important.

Some Availability But Limited Accessing of EHRs

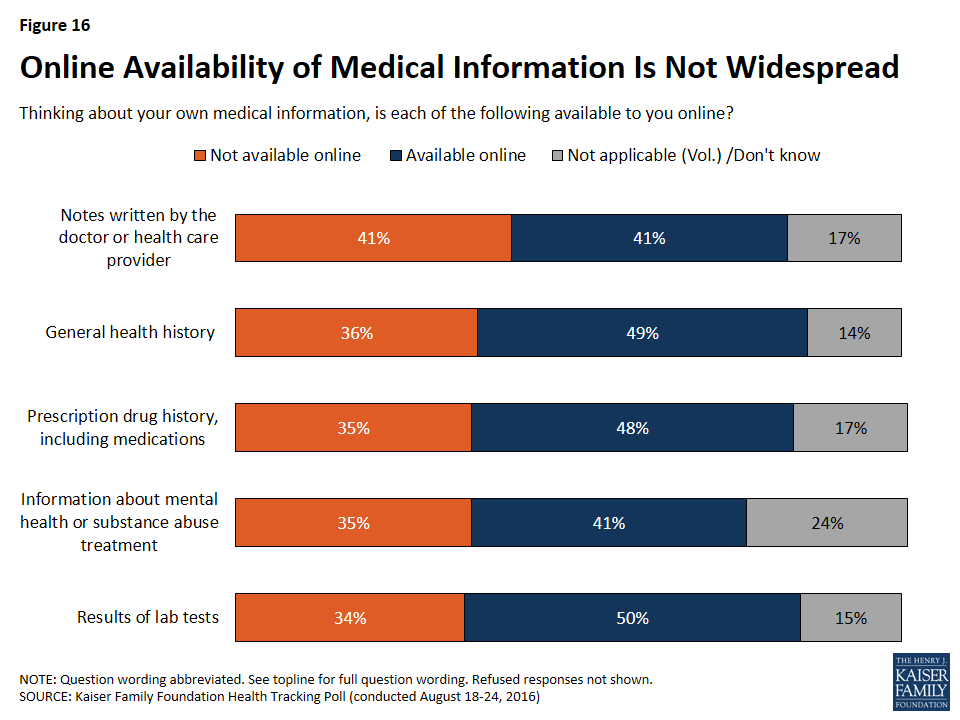

While the vast majority of Americans say it is important for their health care provider to use electronic medical records and most say that being able to access different types of medical information is important, a large share currently say their medical information is not available online. Across all the different types of health information, about a third say these types of information are not currently available to them online, with a slightly larger share (41 percent) saying the notes written by their doctor or health provider are not available.

While 78 percent of Americans report that at least some of their medical information is available online, much smaller shares report accessing this information. Less than half of Americans report having accessed any type of medical information online. When they do access medical information, 29 percent say they have accessed the results of lab tests, such as blood tests, x-rays, and mammograms, 26 percent say they have accessed general health history, 23 percent say they have accessed prescription drug history, and 21 percent say they have accessed notes written by their doctor or health care provider. A much smaller share report accessing information about mental health or substance abuse treatment (9 percent).

Majority of Americans Have Security or Privacy Concerns Regarding Online Medical Records

About eight in ten (78 percent) Americans have at least some medical records and personal health information available online. Of these, 60 percent (47 percent of total population) say they are either “very” or “somewhat” concerned that an unauthorized person might get access to their confidential records and information. Larger shares of Hispanic individuals (58 percent of total) and Blacks (56 percent of total) report having privacy concerns than Whites (42 percent of total).

Why Some Americans Still Don’t Access Online Medical Records

One-third of Americans report that they have the ability to access their medical records or personal health information online but have not done so. The main reason given is that they did not have a need to access the information (49 percent), followed by not having access to the internet (15 percent), not knowing how to access the information (13 percent), and being concerned about privacy or security (11 percent).

In addition, accessing online medical records or health information is seemingly dependent on education level and income, but noticeably, not on age. Almost half of individuals who have not accessed their own medical records have a high school diploma or less (49 percent) or earn less than $40,00 a year (47 percent).

| Table 3: Demographics of Those Who Have and Have Not Accessed Their Own Medical Records or Personal Health Information Online | |||

| Have Accessed | Have Not Accessed | Total | |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 31% | 49% | 40% |

| Some college | 30 | 31 | 30 |

| College+ | 39 | 20 | 29 |

| Income | |||

| <$40K | 34 | 47 | 40 |

| $40K to less than $90K | 29 | 31 | 30 |

| >$90K | 26 | 12 | 20 |

| Age | |||

| 18-29 | 19 | 21 | 20 |

| 30-49 | 35 | 30 | 32 |

| 50-64 | 29 | 28 | 29 |

| 65+ | 17 | 20 | 19 |

Kaiser Health Policy News Index: August 2016

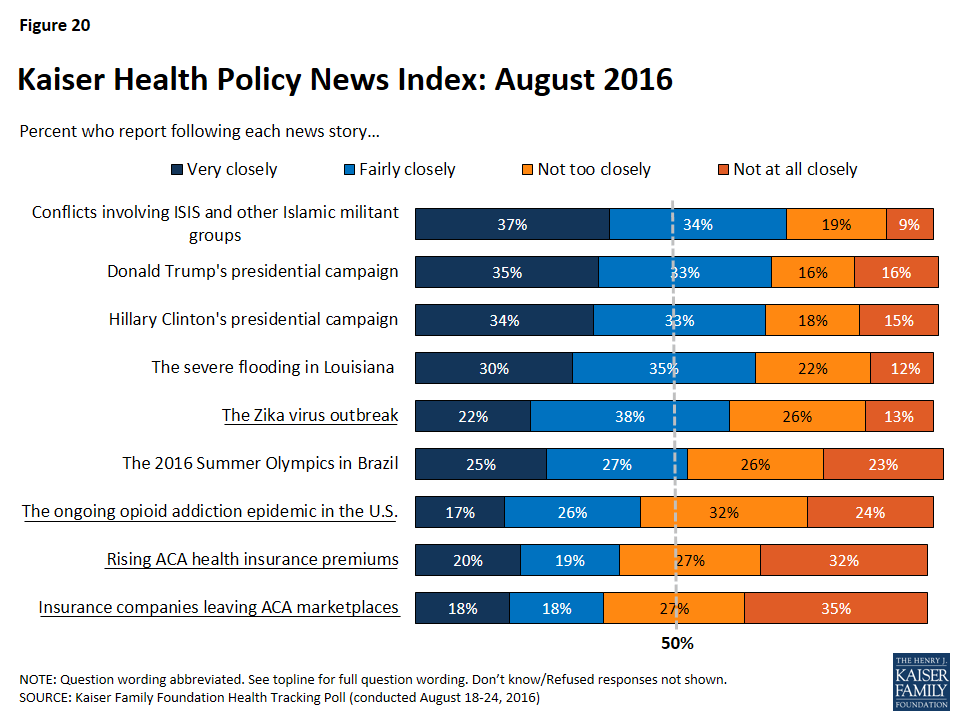

The August Kaiser Health Tracking Poll finds that the majority of Americans (71 percent) are following stories about conflicts involving ISIS and other Islamic militant groups as well as both Donald Trump’s presidential campaign (68 percent) and Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign (67 percent). Other stories that capture the attention of Americans this month include the severe flooding in Louisiana (65 percent) and the Zika virus outbreak (60 percent). About half of Americans say they have been following stories about the 2016 Summer Olympics, which took place in Brazil from August 5th to 21st. While a majority of the public say they follow news about the Zika virus outbreak, fewer Americans report following three additional health policy stories: the ongoing heroin and prescription painkiller addiction epidemic in the U.S. (43 percent), reports about rising ACA health insurance premiums (39 percent), and news of health insurance companies leaving ACA marketplaces (36 percent).

Methodology

This Kaiser Health Tracking Poll was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The survey was conducted August 18-24, 2016, among a nationally representative random digit dial telephone sample of 1,211 adults ages 18 and older, living in the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). Computer-assisted telephone interviews conducted by landline (423) and cell phone (788, including 473 who had no landline telephone) were carried out in English and Spanish by Princeton Data Source under the direction of Princeton Survey Research Associates International (PSRAI). Both the random digit dial landline and cell phone samples were provided by Survey Sampling International, LLC. For the landline sample, respondents were selected by asking for the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the opposite gender. For the cell phone sample, interviews were conducted with the adult who answered the phone. KFF paid for all costs associated with the survey.

The combined landline and cell phone sample was weighted to balance the sample demographics to match estimates for the national population using data from the Census Bureau’s 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) on sex, age, education, race, Hispanic origin, and region along with data from the 2010 Census on population density. The sample was also weighted to match current patterns of telephone use using data from the July-December 2015 National Health Interview Survey. The weight takes into account the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection in the combined sample and also adjusts for the household size for the landline sample. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total | 1211 | ±3 percentage points |

| Registered Voters | ||

| Total RV | 1020 | ±4 percentage points |

| Democratic RV | 340 | ±6 percentage points |

| Republican RV | 256 | ±7 percentage points |

| Independent RV | 340 | ±6 percentage points |

| Party Identification | ||

| Democrats | 381 | ±6 percentage points |

| Republicans | 286 | ±7 percentage points |

| Independents | 404 | ±6 percentage points |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 630 | ±5 percentage points |

| Women | 581 | ±5 percentage points |

| Zika Travel Warnings | ||

| Aware of domestic travel warnings related to Zika | 742 | ±4 percentage points |

| Say there aren’t domestic travel warnings related to Zika | 308 | ±6 percentage points |

Endnotes

- See previous KFF Health Tracking Polls including the July 2016 Tracking Poll which found that about one-third of voters say health care is “extremely important” to their vote for president this year, https://modern.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-july-2016/. ↩︎

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2016/08/01/florida-announces-10-new-zika-cases-a-travel-advisory-is-expected/ The Centers for Disease Control has since expanded their warning after new cases of local transmission were confirmed in another neighborhood. ↩︎

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/zika-is-spreading-in-florida-but-congress-still-hasnt-approved-cash-to-fight-it/2016/08/23/cafe91e2-6966-11e6-99bf-f0cf3a6449a6_story.html?utm_term=.e96a1d4a23ea ↩︎

- https://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/health-it-legislation ↩︎

- https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/the-public-and-the-health-care-delivery-2/ ↩︎

Campaign 2016: Voters Give Clinton Wide Edge Over Trump on Trust to Handle Health Care Issues; ACA Ranks Lower Among Health Issues Voters Want Discussed

Zika Outbreak: Half of Public Would Be Uncomfortable Visiting Affected Parts of Florida; Large Majority Says New Zika Funding Is a Top or Important Priority for Congress

Electronic Medical Records: Eight in 10 Americans Say It Is Important for Providers to Computerize Records, But Half Worry About Unauthorized Access to Online Information

With the 2016 elections just 10 weeks away, voters give Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton a substantial advantage over Republican nominee Donald Trump on a wide array of health care issues, the latest Kaiser Health Tracking Poll finds.

Two thirds of voters (66%), including large shares of Democrats, Republicans, and independents, identify access and affordability of health care and the future of Medicare, an issue not being widely discussed on the campaign trail, as top priorities for the presidential candidates to talk about during the campaign. Smaller majorities of voters say the same about Medicaid’s future (54%), prescription drug costs (53%), and the future of the 2010 health care law (52%).

On each of those issues and several other health policy issues, more voters say they trust Clinton to do a better job than say they trust Trump, the poll finds. For example, Clinton leads Trump on Medicare’s future (53% compared to 38%), access and affordability to health care (52% to 39%), Medicaid’s future (54% to 37%), prescription drug costs (51% to 39%), and the Zika virus outbreak (54% to 34%). Among the nine issues asked about, Clinton’s largest lead is 36 percentage points on women’s access to reproductive health care (64% to 28%), while her smallest lead is on the future of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (50% to 41%).

A majority of female voters (71%) say they trust Clinton to do a better job on women’s access to reproductive health services compared to one in five (20%) who say they trust Trump. Voters, age 65 and older, are split between which candidate they trust to do a better job dealing with the future of Medicare with a similar share saying they trust Trump (44%) as saying they trust Clinton (47%).

In spite of Clinton’s edge with voters on these issues, most voters don’t expect much improvement in access to affordable care regardless of who wins the election. A third (33%) of voters say access to affordable care would get better across the country generally if Clinton wins; a similar share (29%) say so if Trump were to win. The poll also shows few voters expect their own ability to access affordable care to improve under either candidate. On each question, more voters say they expect the situation to get worse if Trump were elected than if Clinton were elected.

KFF has been tracking public opinion on the Zika virus outbreak since February 2016, and this month’s survey finds three quarters (76%) of the public are aware that people in the United States have become infected from the bite of mosquitoes locally. A smaller majority (58%) is aware that travel warnings have been issued for areas in the United States affected by the outbreak.

About half of the public (48%) say that they would not be comfortable traveling to places in the United States, like parts of Florida, where people have been infected by mosquitoes. Slightly more say the same about traveling to U.S. territories like Puerto Rico or to places outside the United States where people have become infected (59% and 61%, respectively).

With Congress set to return from its August recess after Labor Day, the poll finds a third (36%) of the public views passing new funding to combat Zika as a top priority for Congress. An additional 40 percent say it is an important, but not top, priority. Democrats are more likely than Republicans or independents to view Zika as a top Congressional priority, though large majorities within each group consider it at least an important priority.

The survey also probes the public’s experience and views with electronic medical records. Today, 80 percent of the public says their doctor or other healthcare provider usually enters their health information into a computer while they are present – up sharply since 2009, when an earlier KFF poll found 46 percent said this usually happened. Half (52%) now say it is “very important” for their providers to use electronic medical records, up from 42 percent in 2009.

About eight in ten (78%) Americans say they have at least some medical records and personal health information available online. Of these, 60 percent (47% of total population) say they are either “very” or “somewhat” concerned that an unauthorized person might get access to their confidential records and information.

Other poll findings include:

- Americans’ opinion of the health care law remains split with 40 percent saying they have a favorable view and 42 percent saying they have an unfavorable view.

- When asked about the news media’s coverage of the health reform law, four in ten say that the coverage is mostly balanced while 27 percent say it is biased in favor of the law and 21 percent say it is biased against the law. About half (47 percent) of Republicans say the news media coverage of the health reform law is biased in favor of the law while half of Democrats and 43 percent of independents say the news coverage is mostly balanced.

Designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation, the poll was conducted from August 18-24 among a nationally representative random digit dial telephone sample of 1,211 adults. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish by landline (423) and cell phone (788). The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points for the full sample. For results based on subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher.

Preliminary Data on Insurer Exits and Entrants in 2017 Affordable Care Act Marketplaces

In October 2016, the Foundation issued a updated version of this analysis with a new county-level interactive map and slideshow

The following charts provide a preliminary picture of the potential effect insurer exits and entrants may have on competition and consumer choice in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces. This analysis was done at the request of the Wall Street Journal. Our earlier analysis found that UnitedHealth’s absence from these markets would leave many parts of the country with fewer marketplace insurers, and that the number of counties with a single insurer would likely increase substantially if there were no new entrants. Similarly, our July analysis of insurer participation in 17 states with detailed, publicly available premium and participation data found that on average there would be fewer insurers participating in 2017 in these states than there had been in 2016 or 2015.

Since the time of our earlier analyses, more details have emerged on the degree to which some insurance companies, most recently Aetna and Oscar, are planning to scale back or withdrawing their participation on the marketplaces. Meanwhile other insurers, including Cigna, have noted their intent to enter into new markets or expand their offerings in their 2017 rate filings to state regulators.

Despite these new details, much is still unknown and the majority of states’ 2017 filings are either redacted or unavailable publicly. Because only premium changes, and not new entrant premiums, are posted on Healthcare.gov’s rate review site, it is also likely that more is known at this time of market exits than is known of entrants. Complete information on insurer participation and premiums across all states does not typically become public until shortly before the beginning of the open enrollment season. It is therefore likely that the complete picture of how entrants and exits are shaping these markets in 2017 will not come into focus for two more months.

Given these limitations, it is too soon to say with certainty how many marketplace insurers enrollees will have available to them when they go to shop for coverage in November. In this analysis, we start with insurers’ participation in 2016 and make adjustments for reported entrants, exits, scale-backs, and expansions. More information on our methods and limitations can be found below. We intend to update this analysis when more complete data are available.

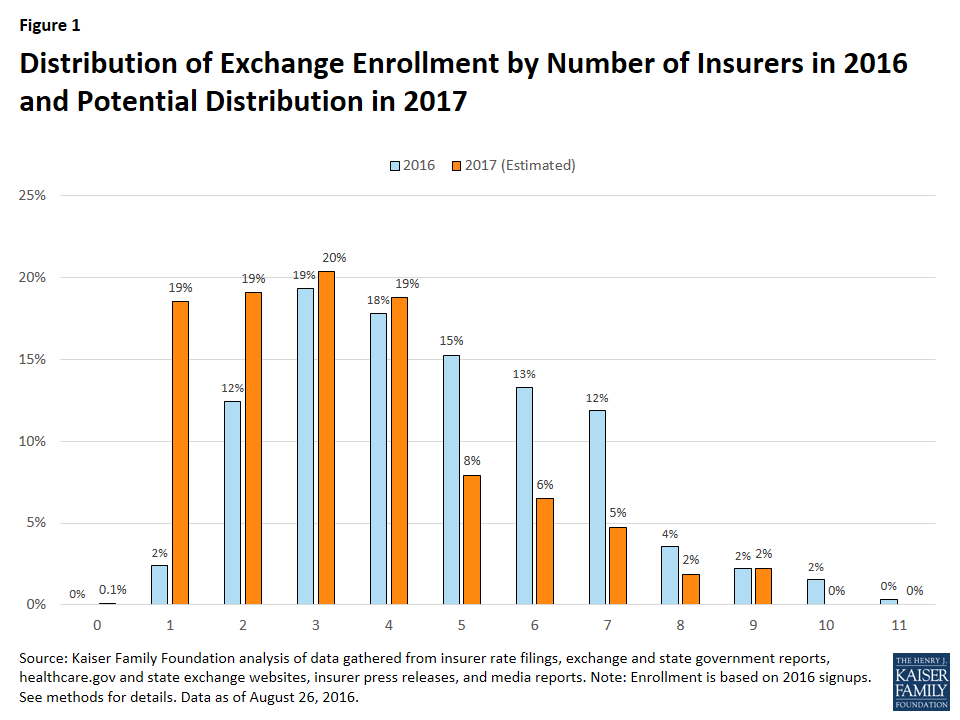

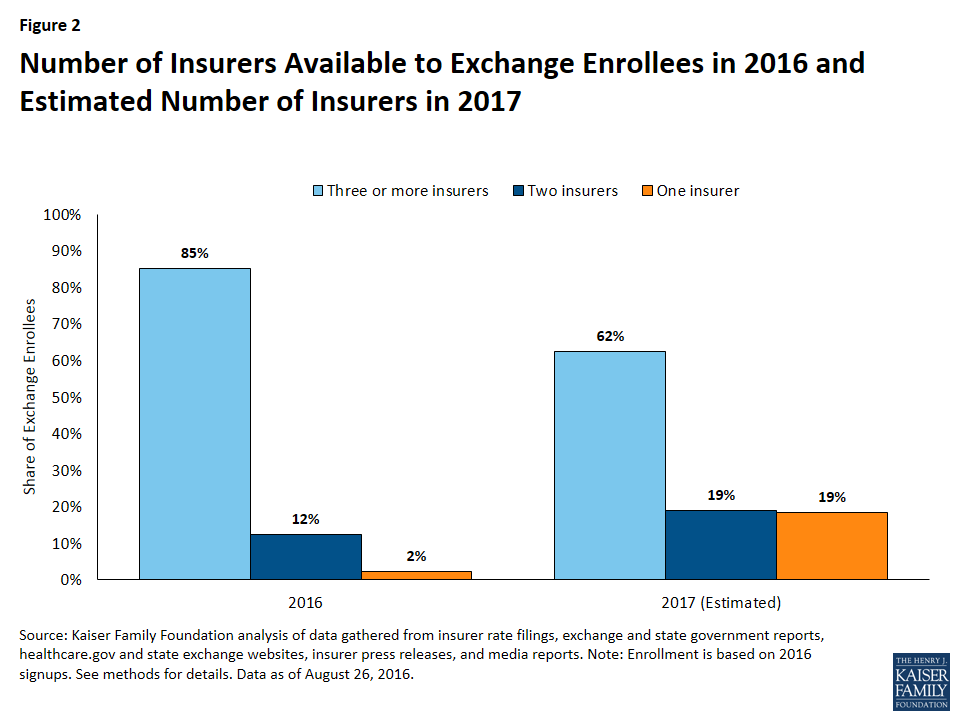

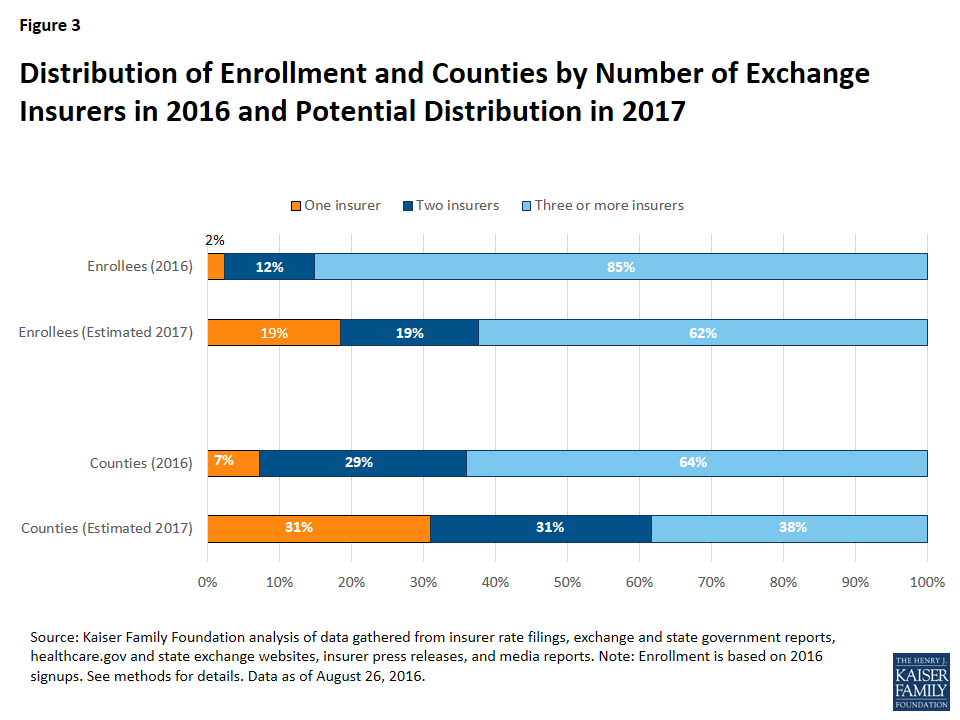

We find that most marketplace enrollees will likely continue to have a choice of three or more plans in 2017, based on what is currently known of marketplace insurer participation and changes next year. However, assuming county-level enrollment holds steady from 2016 to 2017, a smaller share of enrollees will likely have a choice of three or more insurers in 2017 than in previous years. We estimate that 62% of enrollees in 2017 will have a choice of three or more insurers, compared to 85% of enrollees in 2016.

We estimate that 2.3 million marketplace enrollees, or 19% of all enrollees, could have a choice of a single insurer in 2017, which is an increase of 2 million people compared to 2016. Going into marketplace open enrollment in 2016, about 303,000 enrollees (2%) had a single insurer option.

Similarly, we estimate that the number of counties with a single marketplace insurer is likely to increase, from 225 (7% of counties) in 2016 to 974 (31% of counties) in 2017. Approximately 6 in 10 counties could have 2 or fewer marketplace insurers in 2017. The bulk of the increase in single-insurer counties is a result of the UnitedHealth exit, as the company was often the second insurer in rural areas.

In 2016, counties with a single marketplace insurer are concentrated in a handful of states, particularly rural ones: Wyoming (where 100% of counties have one insurer), West Virginia (82%), Utah (69%), South Carolina (63%), and Nevada (59%).

Given what is known at this time of entrants and exits, four additional states are likely to have a single marketplace insurer in all counties: Alabama, Alaska, Oklahoma, and South Carolina, for a total of five states (including Wyoming, which already had one insurer in the state). Other states with significantly more single-insurer counties in 2017 will likely include Arizona (87% of counties in 2017, compared to none in 2016), Mississippi (80% vs. 0%), Missouri (85% vs. 2%), Florida (73% vs. 0%), North Carolina (90% vs. 23%), and Tennessee (60% vs. 0%). With the exception of Alaska, the states left with the most limited exchange participation as a result of 2017 market exits are likely to be in the south.

One county, Pinal County in Arizona, could be at risk of having no insurer options on the marketplace, given what is currently known of exits in the state. However, this could change as another plan that offers elsewhere in the state could expand its service area. In the figures cited in the paragraph above, Pinal County is grouped with single-insurer counties in Arizona.

Rural areas have historically had lower insurer participation, so even one exit can have a significant effect on consumer choice. About 629,000 marketplace enrollees who live in primarily rural counties will likely have a single insurer in 2017, representing 41% of all marketplace enrollees living in mostly rural counties (up from 7% in 2016). Marketplace enrollees living in some urban areas will also have less choice as a result of the exits. As many as 1.7 million enrollees who live in primarily urban counties could have a single marketplace insurer in 2017, representing 15% of all enrollees living in mostly urban counties (up from 2% in 2016).

About 7.9 million enrollees are likely to have three or more choices of marketplace insures in 2017, based on information currently available on entrants and exits. Of these enrollees with at least three choices, the vast majority (7.4 million) live in counties that are primarily urban, while 504,000 live in counties that are primarily rural. Our analysis of information currently available finds that about two out of every three enrollees in primarily urban counties (66%) will likely have a choice of at least three marketplace insurers in 2017, while one in three enrollees in primarily rural counties (33%) are likely to have a choice of three or more insurers.

The map below shows counties where we estimate there could be one or two marketplace insurers in 2017, and the 50-state tables show changes in the number of counties with one insurer from 2016 to 2017 in each state.

| Table 1: Distribution of Counties by Number of Exchange Insurers in 2016 and Potential Distribution in 2017 | ||||||||

| State | 2016 | 2017 (Estimated) | ||||||

| No Insurer | 1 Insurer | 2 Insurer | 3+ Insurer | No Insurer | 1 Insurer | 2 Insurer | 3+ Insurer | |

| AL | – | – | 60 (90%) | 7 (10%) | – | 67 (100%) | – | – |

| AK | – | – | 30 (100%) | – | – | 30 (100%) | – | – |

| AZ | – | – | 8 (53%) | 7 (47%) | 1 (7%) | 12 (80%) | 2 (13%) | – |

| AR | – | – | – | 75 (100%) | – | – | – | 75 (100%) |

| CA | – | – | 1 (2%) | 57 (98%) | – | – | 27 (47%) | 31 (53%) |

| CO | – | – | 4 (6%) | 60 (94%) | – | – | 47 (73%) | 17 (27%) |

| CT | – | – | – | 8 (100%) | – | – | 8 (100%) | – |

| DE | – | – | 3 (100%) | – | – | – | 3 (100%) | – |

| DC | – | – | 1 (100%) | – | – | – | 1 (100%) | – |

| FL | – | – | 44 (66%) | 23 (34%) | – | 49 (73%) | 8 (12%) | 10 (15%) |

| GA | – | – | 30 (19%) | 129 (81%) | – | 77 (48%) | 49 (31%) | 33 (21%) |

| HI | – | – | 5 (100%) | – | – | – | 5 (100%) | – |

| ID | – | – | – | 44 (100%) | – | – | – | 44 (100%) |

| IL | – | – | – | 102 (100%) | – | 8 (8%) | 69 (68%) | 25 (25%) |

| IN | – | – | – | 92 (100%) | – | – | 27 (29%) | 65 (71%) |

| IA | – | – | 21 (21%) | 78 (79%) | – | – | 49 (49%) | 50 (51%) |

| KS | – | – | 105 (100%) | – | – | – | 105 (100%) | – |

| KY | – | – | 66 (55%) | 54 (45%) | – | 54 (45%) | 48 (40%) | 18 (15%) |

| LA | – | – | – | 64 (100%) | – | – | 59 (92%) | 5 (8%) |

| ME | – | – | – | 16 (100%) | – | – | – | 16 (100%) |

| MD | – | – | – | 24 (100%) | – | – | – | 24 (100%) |

| MA | – | – | – | 14 (100%) | – | – | – | 14 (100%) |

| MI | – | 14 (17%) | 24 (29%) | 45 (54%) | – | 14 (17%) | 27 (33%) | 42 (51%) |

| MN | – | – | – | 87 (100%) | – | – | 26 (30%) | 61 (70%) |

| MS | – | – | 50 (61%) | 32 (39%) | – | 66 (80%) | 16 (20%) | – |

| MO | – | – | 2 (2%) | 113 (98%) | – | 98 (85%) | 13 (11%) | 4 (3%) |

| MT | – | – | – | 56 (100%) | – | – | – | 56 (100%) |

| NE | – | – | – | 93 (100%) | – | – | 2 (2%) | 91 (98%) |

| NV | – | 10 (59%) | 4 (24%) | 3 (18%) | – | 10 (59%) | 4 (24%) | 3 (18%) |

| NH | – | – | – | 10 (100%) | – | – | – | 10 (100%) |

| NJ | – | – | – | 21 (100%) | – | – | – | 21 (100%) |

| NM | – | – | – | 33 (100%) | – | – | – | 33 (100%) |

| NY | – | – | 3 (5%) | 59 (95%) | – | – | 3 (5%) | 59 (95%) |

| NC | – | 23 (23%) | 38 (38%) | 39 (39%) | – | 90 (90%) | 10 (10%) | – |

| ND | – | – | 4 (8%) | 49 (92%) | – | – | 4 (8%) | 49 (92%) |

| OH | – | – | – | 88 (100%) | – | – | 5 (6%) | 83 (94%) |

| OK | – | – | 77 (100%) | – | – | 77 (100%) | – | – |

| OR | – | – | – | 36 (100%) | – | – | – | 36 (100%) |

| PA | – | – | – | 67 (100%) | – | 5 (7%) | 34 (51%) | 28 (42%) |

| RI | – | – | – | 5 (100%) | – | – | 5 (100%) | – |

| SC | – | 29 (63%) | 15 (33%) | 2 (4%) | – | 46 (100%) | – | – |

| SD | – | – | 66 (100%) | – | – | – | 66 (100%) | – |

| TN | – | – | 57 (60%) | 38 (40%) | – | 57 (60%) | 24 (25%) | 14 (15%) |

| TX | – | 58 (23%) | 110 (43%) | 86 (34%) | – | 88 (35%) | 129 (51%) | 37 (15%) |

| UT | – | 20 (69%) | 3 (10%) | 6 (21%) | – | 20 (69%) | 2 (7%) | 7 (24%) |

| VT | – | – | 14 (100%) | – | – | – | 14 (100%) | – |

| VA | – | – | 37 (28%) | 97 (72%) | – | 29 (22%) | 38 (28%) | 67 (50%) |

| WA | – | – | 6 (15%) | 33 (85%) | – | 5 (13%) | 11 (28%) | 23 (59%) |

| WV | – | 45 (82%) | 10 (18%) | – | – | 45 (82%) | 10 (18%) | – |

| WI | – | 3 (4%) | 7 (10%) | 62 (86%) | – | 4 (6%) | 13 (18%) | 55 (76%) |

| WY | – | 23 (100%) | – | – | – | 23 (100%) | – | – |

| US | – | 225 (7%) | 905 (29%) | 2,014 (64%) | 1 (0%) | 974 (31%) | 963 (31%) | 1,206 (38%) |

| Source: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis as of August 26, 2016. | ||||||||

| Table 2: Distribution of Enrollees by Number of Exchange Insurers in 2016 and Potential Distribution in 2017 | ||||||||

| State | 2016 | 2017 (Estimated) | ||||||

| No Insurer | 1 Insurer | 2 Insurer | 3+ Insurer | No Insurer | 1 Insurer | 2 Insurer | 3+ Insurer | |

| AL | – | – | 130,000 (67%) | 65,000 (33%) | – | 195,000 (100%) | – | – |

| AK | – | – | 23,000 (100%) | – | – | 23,000 (100%) | – | – |

| AZ | – | – | 31,000 (15%) | 172,000 (85%) | 10,000 (5%) | 36,000 (18%) | 157,000 (78%) | – |

| AR | – | – | – | 74,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 74,000 (100%) |

| CA | – | – | 1,000 (0%) | 1,575,000 (100%) | – | – | 86,000 (5%) | 1,489,000 (95%) |

| CO | – | – | 8,000 (5%) | 143,000 (95%) | – | – | 30,000 (20%) | 120,000 (80%) |

| CT | – | – | – | 116,000 (100%) | – | – | 116,000 (100%) | – |

| DE | – | – | 28,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 28,000 (100%) | – |

| DC | – | – | 23,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 23,000 (100%) | – |

| FL | – | – | 268,000 (15%) | 1,475,000 (85%) | – | 352,000 (20%) | 258,000 (15%) | 1,133,000 (65%) |

| GA | – | – | 20,000 (3%) | 568,000 (97%) | – | 81,000 (14%) | 83,000 (14%) | 424,000 (72%) |

| HI | – | – | 15,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 15,000 (100%) | – |

| ID | – | – | – | 101,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 101,000 (100%) |

| IL | – | – | – | 388,000 (100%) | – | 56,000 (14%) | 99,000 (26%) | 233,000 (60%) |

| IN | – | – | – | 196,000 (100%) | – | – | 24,000 (12%) | 172,000 (88%) |

| IA | – | – | 5,000 (10%) | 50,000 (90%) | – | – | 17,000 (31%) | 38,000 (69%) |

| KS | – | – | 102,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 102,000 (100%) | – |

| KY | – | – | 31,000 (33%) | 63,000 (67%) | – | 26,000 (28%) | 32,000 (35%) | 35,000 (38%) |

| LA | – | – | – | 214,000 (100%) | – | – | 131,000 (61%) | 83,000 (39%) |

| ME | – | – | – | 84,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 84,000 (100%) |

| MD | – | – | – | 162,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 162,000 (100%) |

| MA | – | – | – | 214,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 214,000 (100%) |

| MI | – | 13,000 (4%) | 57,000 (17%) | 276,000 (80%) | – | 13,000 (4%) | 59,000 (17%) | 274,000 (79%) |

| MN | – | – | – | 84,000 (100%) | – | – | 13,000 (16%) | 70,000 (84%) |

| MS | – | – | 47,000 (43%) | 62,000 (57%) | – | 63,000 (58%) | 46,000 (42%) | – |

| MO | – | – | 4,000 (1%) | 286,000 (99%) | – | 101,000 (35%) | 136,000 (47%) | 53,000 (18%) |

| MT | – | – | – | 58,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 58,000 (100%) |

| NE | – | – | – | 88,000 (100%) | – | – | 1,000 (1%) | 87,000 (99%) |

| NV | – | 3,000 (3%) | 6,000 (7%) | 79,000 (90%) | – | 3,000 (3%) | 6,000 (7%) | 79,000 (90%) |

| NH | – | – | – | 55,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 55,000 (100%) |

| NJ | – | – | – | 289,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 289,000 (100%) |

| NM | – | – | – | 55,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 55,000 (100%) |

| NY | – | – | 2,000 (1%) | 269,000 (99%) | – | – | 2,000 (1%) | 269,000 (99%) |

| NC | – | 50,000 (8%) | 155,000 (25%) | 409,000 (67%) | – | 490,000 (80%) | 123,000 (20%) | – |

| ND | – | – | 1,000 (3%) | 21,000 (97%) | – | – | 1,000 (3%) | 21,000 (97%) |

| OH | – | – | – | 244,000 (100%) | – | – | 3,000 (1%) | 241,000 (99%) |

| OK | – | – | 145,000 (100%) | – | – | 145,000 (100%) | – | – |

| OR | – | – | – | 147,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 147,000 (100%) |

| PA | – | – | – | 439,000 (100%) | – | 173,000 (39%) | 143,000 (33%) | 124,000 (28%) |

| RI | – | – | – | 35,000 (100%) | – | – | 35,000 (100%) | – |

| SC | – | 91,000 (39%) | 116,000 (50%) | 25,000 (11%) | – | 232,000 (100%) | – | – |

| SD | – | – | 26,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 26,000 (100%) | – |

| TN | – | – | 79,000 (29%) | 190,000 (71%) | – | 79,000 (29%) | 69,000 (26%) | 121,000 (45%) |

| TX | – | 55,000 (4%) | 123,000 (9%) | 1,128,000 (86%) | – | 162,000 (12%) | 383,000 (29%) | 761,000 (58%) |

| UT | – | 34,000 (19%) | 6,000 (3%) | 136,000 (77%) | – | 34,000 (19%) | 3,000 (2%) | 139,000 (79%) |

| VT | – | – | 29,000 (100%) | – | – | – | 29,000 (100%) | – |