February State Data for Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas

Issue Brief

Arkansas is one of eight states for which CMS has approved a Section 1115 waiver to condition Medicaid eligibility on meeting work and reporting requirements and the first state to implement this type of waiver.1 The new requirements were phased in for most enrollees ages 30-492 beginning in June 2018 and for individuals ages 19-29 starting in January 2019. Unless exempt, enrollees must engage in 80 hours of work or other qualifying activities each month and must report their work or exemption status by the 5th of the following month using an online portal; as of mid-December 2018, they also may report by phone.3 Monthly data related to the new requirements released by the Arkansas Department of Human Services show that over 18,000 people were disenrolled from Medicaid for failure to comply with the new requirements in 2018. Those who fail to comply with the requirements for any three months in 2019 can lose coverage beginning in April 2019,4 unless a federal district court ruling prevents new coverage losses from going into effect.5 This brief looks at data for February 2019. Separate reports look at early implementation of the new requirements and enrollee experiences.

How many people have lost or are at risk of losing coverage due to the work and reporting requirements?

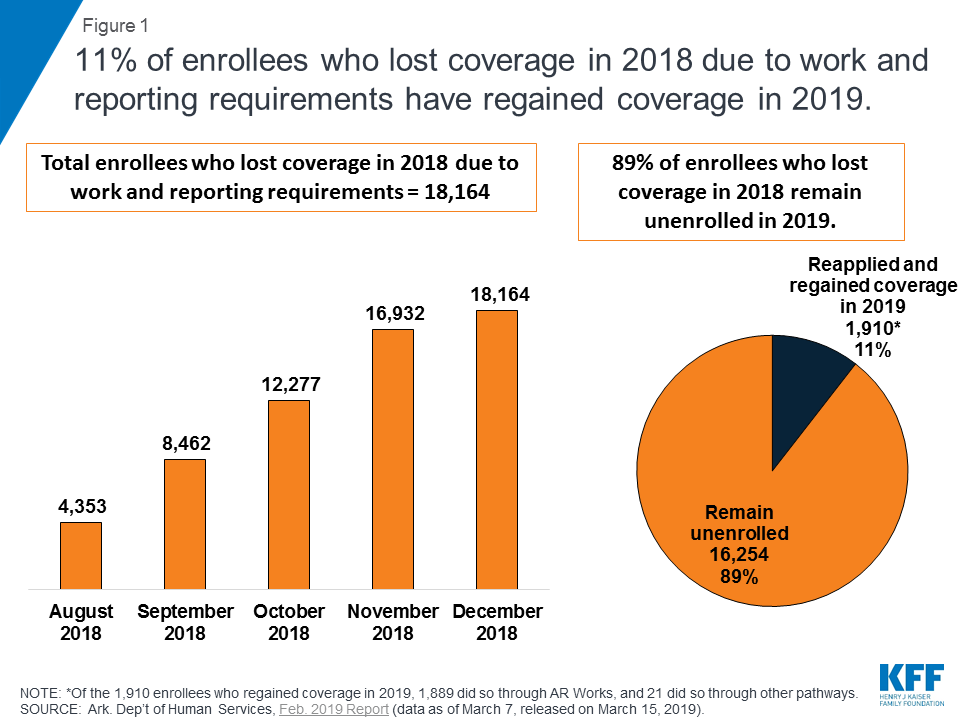

A total of 18,164 individuals lost coverage in 2018 due to failure to meet the work and reporting requirements, and few have regained coverage in 2019 (Figure 1). Under the waiver, enrollees lose coverage for the rest of the calendar year after not meeting the requirements for any three months and are barred from regaining coverage until the following January. Of the 18,164 individuals who lost coverage in 2018, 11%, or 1,910, have reapplied for and regained coverage in 2019.6 The data do not indicate whether those who remain unenrolled have obtained other coverage or are uninsured. Other research shows that additional administrative burdens on eligibility and enrollment processes, such as having to re-apply to regain coverage, result in some eligible people remaining unenrolled.

As of March 7, 2019, 7,066 enrollees had one month of non-compliance with the requirements, and 6,472 enrollees had two months of non-compliance in the new calendar year. Each enrollee’s count of noncompliance months reset to zero at the beginning of 2019. Those with two months of non-compliance in 2019 are at risk of losing coverage in April if they fail to meet the work or reporting requirements in March, or later in 2019 if they fail to meet the requirements in another subsequent month.

In February 2019, almost 5% (10,854) of all Arkansas Works enrollees had their cases closed for reasons other than failure to meet the work and reporting requirements. Nearly half (49%) of total case closures were due to problems with communication (i.e., 19% due to inability to locate client or client moved out of state, and 30% due to failure to return requested information).7 Some of these statistics can be explained from information learned from enrollee focus groups, which revealed that some individuals (especially college students or individuals who move in and out of homelessness) did not receive notices due to address changes; some enrollees were not receiving notices at their correct address, despite having reported an address change to the state. Focus group participants also described confusion when monthly reporting for the work requirement coincided with the need to separately provide similar information to the state for their annual eligibility renewal. Other research shows that any additional administrative burdens on eligibility and enrollment processes result in loss of coverage among those who remain eligible.

How many enrollees are subject to the work and reporting requirements?

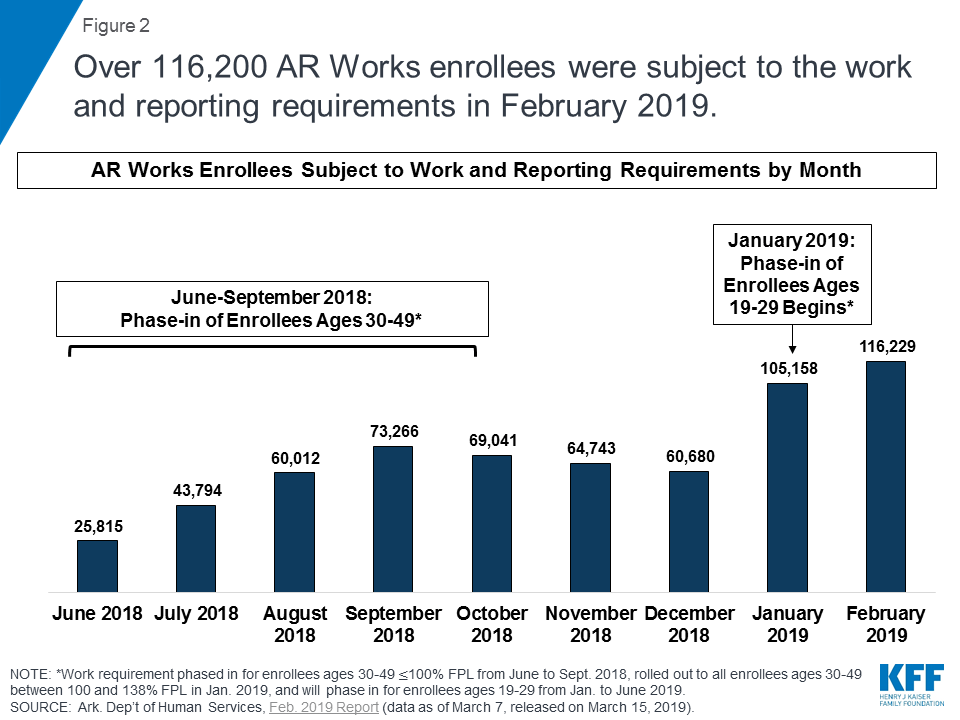

A total of 116,229 individuals were subject to the work and reporting requirements in February 2019, an 11% increase over January as more enrollees continued to be phased in. The work and reporting requirements were phased in for enrollees ages 30-49 at or below 100% FPL from June to September 2018, rolled out to all enrollees ages 30-49 between 101 and 138% FPL in January 2019, and are phasing in for all enrollees ages 19-29 from January to June 2019. (Figure 2). Those subject to the new requirements account for half of the 238,870 Arkansas Works enrollees as of February 2, 2019. Those ages 50 and older are not subject to the requirements.

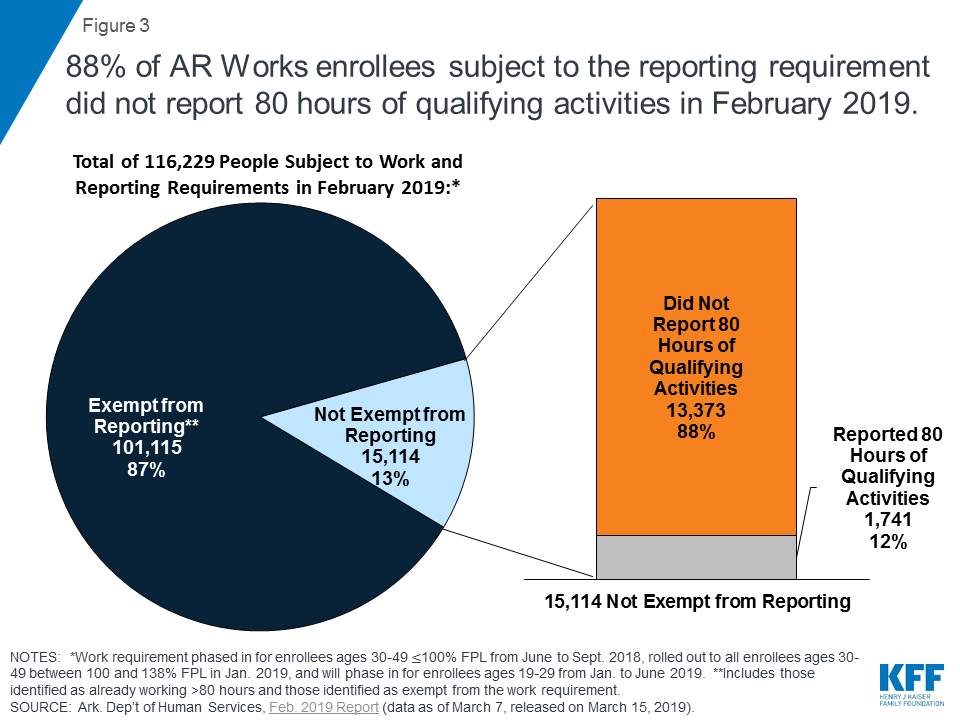

Nearly 9 out of 10 (88%) of those not exempt from the work and/or reporting requirements did not report 80 hours of qualifying activities in February (Figure 3). The large majority (87%) of individuals subject to the work requirements were exempt from the reporting requirements. Of those required to report, only 12% reported 80 hours of qualifying activities.8

Consistent with prior months, nearly all enrollees (almost 99%) who failed to report 80 hours of qualifying activities reported no work activities. This could mean that they did not create and link the online accounts required to enable them to report online, they experienced difficulty accessing or navigating the online portal, or they were unable to report successfully by phone. A small number of enrollees (197 out of 13,373) did report some work activities, but not 80 hours of qualifying activities.9 Individuals who fail to complete 80 hours of qualifying work activities and/or fail to timely report their activities each month can request a good cause exception. From June 2018 through February 2019, the state reviewed a total of 1,017 good cause requests; of these, the state granted 676, denied 77, determined that 263 were “not a good cause issue,” and noted that verification was not received for one request.10

How many enrollees were exempt from the work and reporting requirements and why?

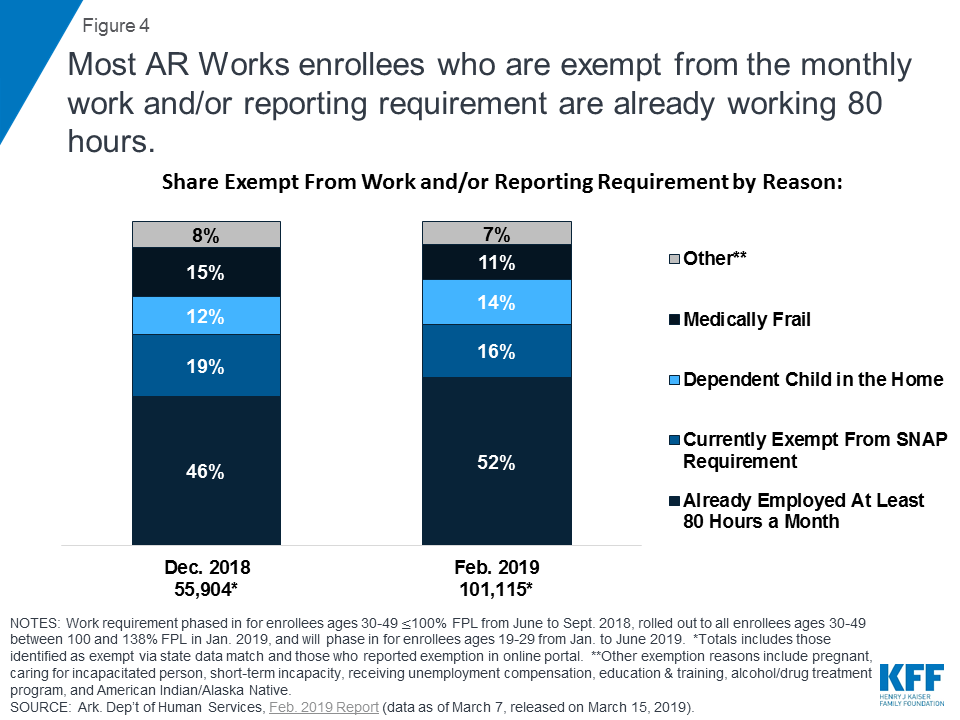

Most of the enrollees exempt from the reporting requirement in February were already working at least 80 hours per month. These 101,115 enrollees who were exempt from reporting represent 98% of those who met the requirements in February. The state identified many of these enrollees through a data match, and they should have received a notice indicating that they were subject to the work requirement but exempt from the reporting requirement. Overall, most exempt enrollees fell into four categories: those who were already working at least 80 hours per month, followed by those currently exempt from SNAP employment and training requirements, those with a dependent child in the household, and those identified as medically frail (Figure 4).11 While the shares falling into these categories were nearly identical in January and February, some of the shares of exemption categories shifted compared to December, with more enrollees identified through the state data match as already working 80 hours and fewer exempt due to SNAP compliance or medical frailty. These shifts are consistent with the phase-in of the enrollees ages 30-49 at 101-138% FPL in January, as enrollees at that income level are likely to be working already. State data about enrollees who are working do not indicate whether the individual newly obtained a job as a result of the new requirements.

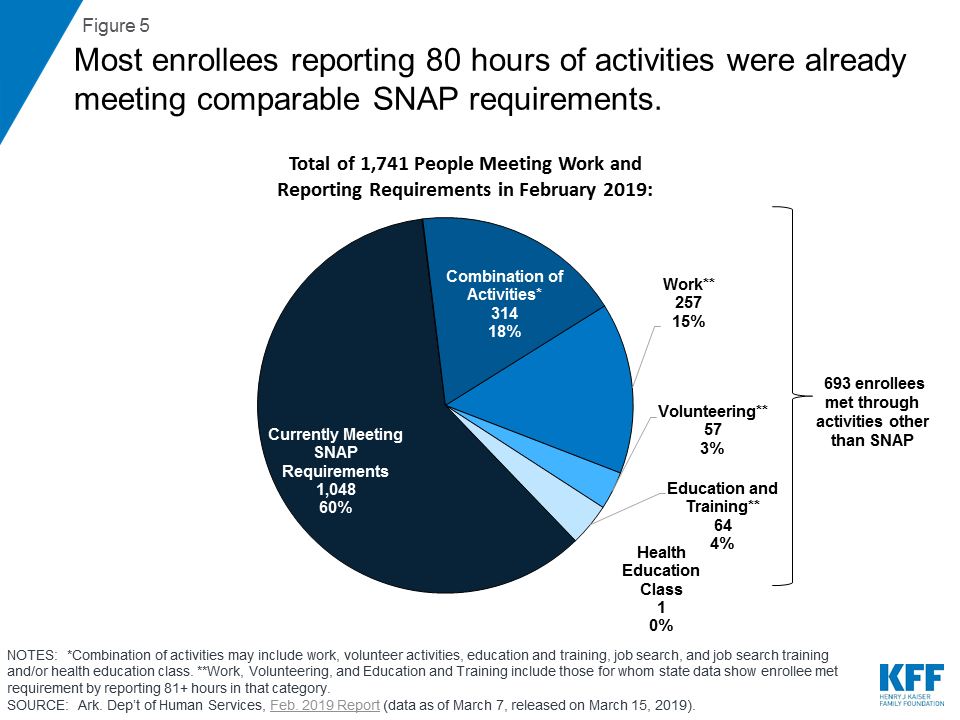

How many enrollees actively met the reporting requirement and through what activities?

Less than 2% of enrollees who met the requirements in February 2019 did so by actively reporting activities, with 60% of this group doing so by meeting comparable SNAP requirements (Figure 5). A small number of enrollees (693) actively reported an activity other than SNAP compliance. The decrease in enrollees reporting compliance with comparable SNAP requirements (from 65% in January to 60% in February) was offset by small increases in the shares reporting work (12% to 15%) or a combination of activities that include work, volunteer activities, education and training, job search, job search training, and/or health education classes (15% to 18%). It is unclear if any activities actively reported by enrollees were initiated due to the new requirements.

What will future data reporting and research show?

Despite stakeholder concerns in 2018 about the complex new rules and coverage losses, additional enrollees continue to become newly subject to the work and reporting requirements in 2019. An early look at implementation in fall 2018 found that many enrollees had not been successfully contacted about the new requirements, despite substantial outreach and education efforts and concern that many who remain eligible would lose coverage for failure to navigate the process to verify work status or qualify for an exemption. As a result, over 18,000 people lost coverage for failure to comply with the new requirements over the first seven months of implementation in 2018. In January 2019, two new groups of enrollees — the first phase of those ages 19-29 and all of those ages 30-49 between 101 and 138% FPL — became subject to the requirements, and the 19-29 age group continued to be phased in in February 2019. Changes in state policy in December started to allow reporting by phone, and the state indicated that it would engage in additional outreach and education as new groups face the work and reporting requirements. Research shows that additional reporting or administrative burdens create barriers to eligible people retaining coverage. Going forward, it will be important to monitor the experience of the enrollees newly subject to the requirements in 2019 and assess the effect of policy changes that expand reporting options.

In addition, it will be important to understand more about the characteristics and experience of enrollees who lost coverage. Follow-up with enrollees who lost coverage will provide information about their awareness of the new requirements, their issues with compliance, and whether they gained alternative coverage or are uninsured after leaving Arkansas Works. Early implementation findings point to the potential that coverage losses will result in gaps in care and increased uncompensated care costs. Additional research is needed to examine the longer-term effects of coverage losses and lock-outs for enrollees, providers, and health plans. Over the coming months, it will be important to continue to monitor the status of enrollees and the number who fail to meet the new requirements for three months, putting them at risk of losing coverage in April 2019.

Another development to watch is the federal district court’s decision in the lawsuit challenging the HHS Secretary’s approval of Arkansas’ waiver, including the work and reporting requirements, which is expected by the end of March. Last year, the court set aside Kentucky’s waiver as an invalid exercise of the Secretary’s Section 1115 authority.12 The Medicaid enrollees challenging the Arkansas waiver argue that HHS committed the same error in approving Arkansas’ waiver as it did in Kentucky, by failing to consider the waiver’s impact on coverage. If the court finds that HHS’s approval of Arkansas’ waiver is flawed, it could stop implementation while the case is appealed, which would avert potential disenrollments scheduled for April 2019. The ruling could also have implications for other states implementing or pursuing similar waivers.

Endnotes

- CMS has also approved work requirement waivers in Arizona, Kentucky, Indiana, Michigan, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Wisconsin. CMS approved a work requirement in Maine, but Maine’s new governor rejected the waiver. Work requirement implementation began in Indiana in January, in New Hampshire in March, and is set to begin in Kentucky in July. ↩︎

- In 2018, the work requirement was phased in for those ages 30-49 with income at or below the federal poverty level. In January 2019, the work requirement also was applied to those ages 30-49 between 101% and 138% FPL. ↩︎

- On December 12, 2018, the state issued a press release indicating that enrollees would be able to report work activity by phone with DHS beginning on December 19. ↩︎

- According to state notices, coverage is terminated after the last day of the month (e.g., March 31st) if enrollees were not compliant in two earlier months and did not report 80 hours of qualifying activities by the last day of the month. However, individuals have until the 5th of the following month (e.g., April 5th) to report activities and could have coverage reinstated if they do so. Individuals who were disenrolled due to the work or reporting requirements in 2018 must file a new application to have coverage restored as of January 2019, and all enrollees subject to the new requirements have their non-compliance months reset to zero at the start of the new calendar year. For the next group of enrollees facing coverage loss due to any three months of non-compliance, notices will go out in March to those already non-compliant in two earlier months in 2019, informing recipients that their coverage will terminate as of April 1st but could be reinstated if they report 80 qualifying hours for March by April 5th. ↩︎

- On March 14, 2019, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia heard oral argument in a case brought by a group of Arkansas Medicaid enrollees challenging the U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary’s approval of Arkansas’s Section 1115 waiver including the work and reporting requirements. At the hearing, the judge indicated that he expected to issue a decision before April 1st. Gresham v. Azar, No. 1:18-cv-1900 (D.D.C.). ↩︎

- Of these 1,910 individuals, 1,889 regained coverage through Arkansas Works, meaning that they will again be subject to the work and reporting requirements, and 21 did so through other Medicaid eligibility pathways. ↩︎

- Another 22% of case closures were for unspecified “other” reasons. ↩︎

- The share of those not reporting in February (88%) was similar to the share not reporting in January (87%). ↩︎

- Of those 197 enrollees, 25 reported 80 or more hours of job search or job search training. Each month, however, enrollees are able to count only 39 hours of job search or job search training toward the required 80 hours of qualifying work activities, which means that those engaged in job search or job search training also must complete 41 hours of another qualifying activity or activities to meet the monthly requirement. One enrollee reported over 80 hours of health education classes, but enrollees are only able to count 20 hours of these classes per year. Seventy-five (75) of the 197 enrollees reported work that fell short of the 80-hour requirement in February, including 23 enrollees with at least 61 but fewer than 81 hours of work. Two enrollees reported education and training that fell short of the 80-hour requirement, including 2 with at least 61 but fewer than 81 hours. Nineteen enrollees reported volunteer hours that fell short of the 80-hour requirement, including 2 with at least 61 but fewer than 81 hours. ↩︎

- The state’s quarterly report for July 1, 2018 – September 30, 2018 has additional detail regarding reasons for good cause exemptions. Of the 140 good cause exemptions granted in September 2018, 31 were for failure to work and 109 were for failure to report. The majority of good cause exemptions for failure to work were for an enrollee with a disability (55%). Other reasons include family member disability (13%), hospitalization (13%), life-changing event (6.5%), technical issue (9.7%) or serious illness (3.2%). The large majority of good cause exemptions for failure to report were for technical issues (68%). Other reasons include enrollee disability (10%), hospitalization (6.4%), life-changing event (6.4%), family member disability (5.5%), serious illness (2.8%) and death of family member living in the home (1%). Ark. Dep’t of Human Servs. Ark. Works Program, Nov. 2018 Report (data as of Dec. 7, 2018, released Dec. 17, 2018), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/Health-Care-Independence-Program-Private-Option/ar-works-qtrly-rpt-jul-sep-2018.pdf ↩︎

- Other exemptions, accounting for about 7% of total exemptions, include pregnancy, caring for someone who is incapacitated, short-term incapacity, receiving unemployment benefits, receiving education and training full-time, participating in an alcohol or drug treatment program and American Indian / Alaska Natives. American Indian / Alaska Natives are subject to the requirements but will be phased in at a later date. ↩︎

- The same court also will decide whether HHS’s re-approval of Kentucky’s Section 1115 waiver exceeded the Secretary’s Section 1115 authority. Decisions in both cases are expected simultaneously. The Kentucky decision will address whether HHS has been able to successfully remedy the errors in the original Kentucky waiver approval. This issue bears on whether HHS might be able to similarly correct any errors in the original Arkansas waiver approval. ↩︎