Individual Insurance Market Performance in 2018

Issue Brief

Note: An analysis of first quarter 2019 data for the individual insurance market is available here.

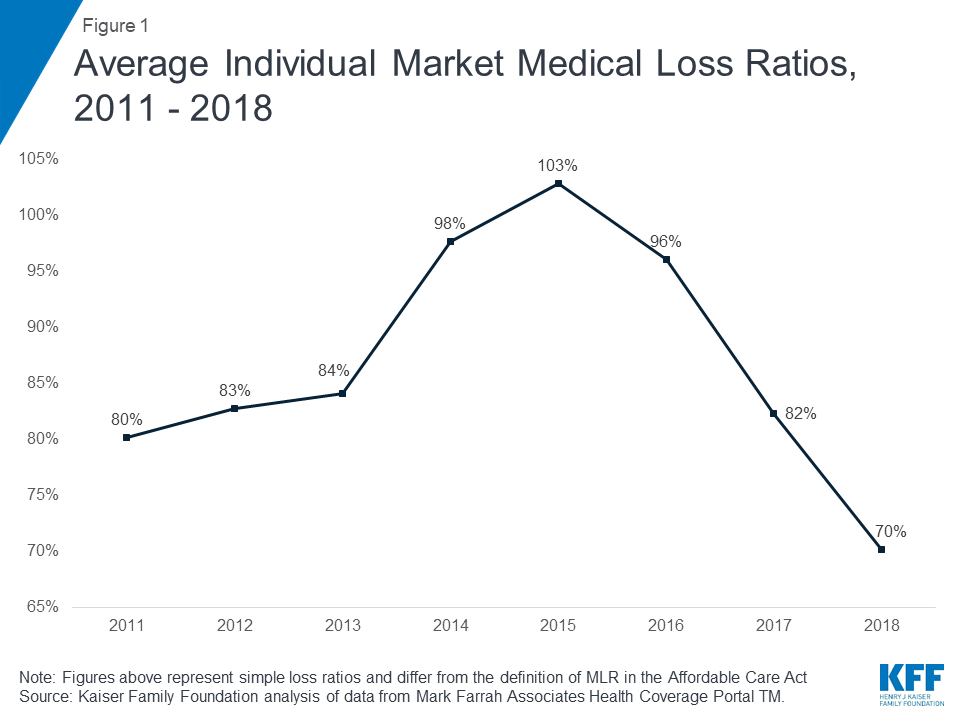

The early years of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) exchanges and broader ACA-compliant individual market were marked by volatility. Markets in some parts of the country have remained fragile, with little competition, an insufficient number of healthy enrollees to balance those who are sick, and high premiums as a result. By 2017, however, the individual market generally had begun to stabilize. Absent any policy changes, it is likely insurers would have required only modest premium increases to regain or maintain profitability in 2018.

However, by mid-2017 when insurers were considering 2018 premiums and participation, it was unclear whether the individual mandate would be enforced, cost-sharing subsidies would be paid, or the ACA as a whole would remain law. In October 2017, the Trump Administration ceased payments for cost-sharing subsidies, which led some insurers to exit the market or request larger premium increases than they would have otherwise. The Administration also reduced funding for advertising and outreach. And, Congress ultimately repealed the individual mandate penalty, effective for 2019. Amid these policy changes and legislative uncertainty, insurers raised benchmark premiums by an average of 34% going into 2018.

In this analysis, we find individual market insurers saw better financial performance in 2018 than in all the earlier years of the ACA and returned to, or even exceeded, pre-ACA levels of profitability. Premiums fell slightly on average for 2019, as it became clear that some insurers had raised 2018 rates more than was necessary. It is likely premiums would have fallen even more if the individual mandate penalty were still in effect.

In this brief, we use financial data reported by insurance companies to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners and compiled by Mark Farrah Associates to look at the average premiums, claims, medical loss ratios, gross margins, and enrollee utilization from 2011 through 2018 in the individual insurance market, as well as the amount of medical loss ratio rebates insurers expect to issue to 2018 enrollees. These figures include coverage purchased through the ACA’s exchange marketplaces and ACA-compliant plans purchased directly from insurers outside the marketplaces (which are part of the same risk pool), as well as individual plans originally purchased before the ACA went into effect.

Our analysis also finds that insurers are expecting to pay a record total of about $800 million in rebates to individual market consumers for not meeting the ACA medical loss ratio threshold, which requires them to spend at least 80% of premium revenues on health care claims or quality improvement activities. This comes from initial estimates reported by insurers; actual rebates could end up being either higher or lower. In total, across the individual, small group, and large group markets, insurers expect to issue about $1.4 billion in rebates this year based on their 2018 performance. If insurer expectations hold true, these will be the largest consumer rebates issued since the MLR program began.

These new data from 2018 offer further evidence that insurers in the individual market are regaining profitability, though more recent policy and legislative changes taking effect in 2019 – the repeal of the individual mandate penalty as part of tax reform legislation and the proliferation of loosely-regulated short-term insurance plans – continue to cloud expectations somewhat for the future.

Medical Loss Ratios

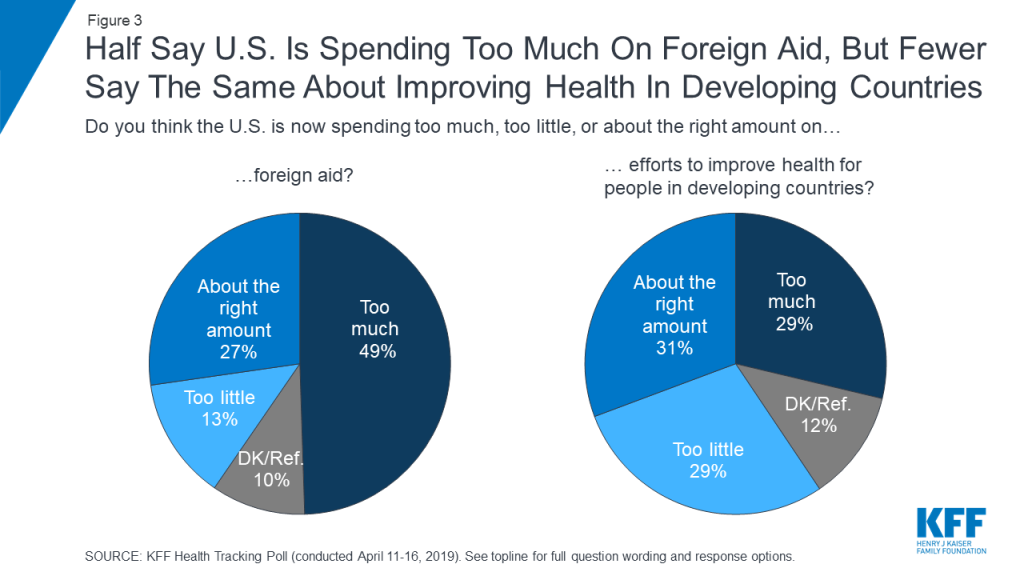

As we found in our previous analysis, insurer financial performance as measured by loss ratios (the share of health premiums paid out as claims) worsened in the earliest years of the ACA Marketplaces, but began to improve more recently. This is to be expected, as the market had just undergone significant regulatory changes in 2014 and insurers had very little information to work with in setting their premiums.

The chart below shows simple loss ratios, which differ from the formula used in the ACA’s MLR provision.1 Loss ratios began to decline in 2016, suggesting improved financial performance. In 2017, following relatively large premium increases, individual market insurers saw significant improvement in loss ratios, a sign that individual market insurers on average were beginning to better match premium revenues to claims costs. Loss ratios have continued to decline, averaging 70% in 2018. This suggests insurers were able to build in the loss of cost-sharing subsidy payments when setting premiums and some insurers likely over-corrected.

Margins

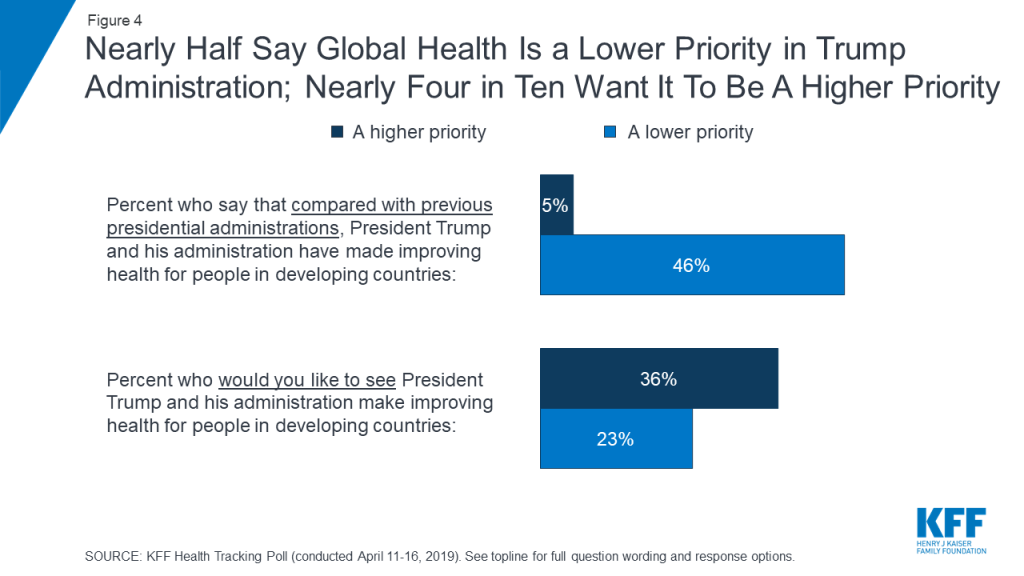

Another way to look at individual market financial performance is to examine average gross margins per member per month, or the average amount by which premium income exceeds claims costs per enrollee in a given month. Gross margins are an indicator of performance, but positive margins do not necessarily translate into profitability since they do not account for administrative expenses.

Gross margins show a similar pattern to loss ratios. Insurer financial performance improved dramatically through 2018 (increasing to $167 per enrollee, from a recent annual low of -$9 in 2015). These data suggest that insurers in this market are now financially healthy, on average.

Underlying Trends

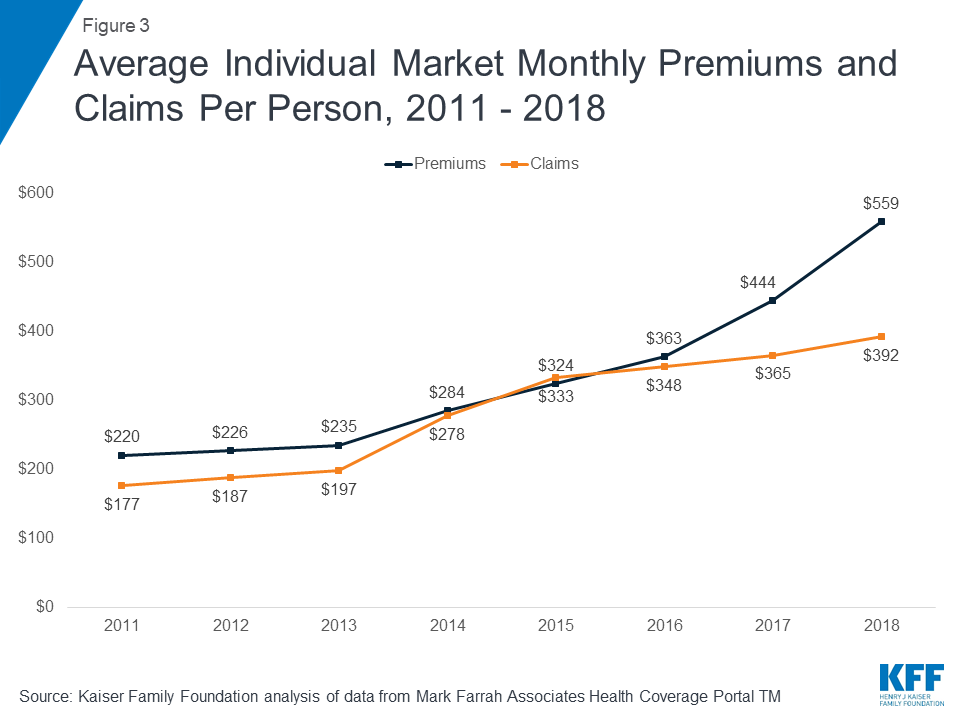

Driving recent improvements in individual market insurer financial performance are the premium increases in 2018 combined with more modest growth in claims for medical expenses. On average, premiums per enrollee grew 26% from 2017 to 2018, while per person claims grew only 7%. This growth in premiums is in part due to the loss of cost-sharing subsidy payments; insurers are required by law to provide cost-sharing subsidies to eligible enrollees, but are no longer being reimbursed by the federal government. Rate hikes to offset the termination of federal cost-sharing subsidy payments were a major factor in 2018 premium increases.

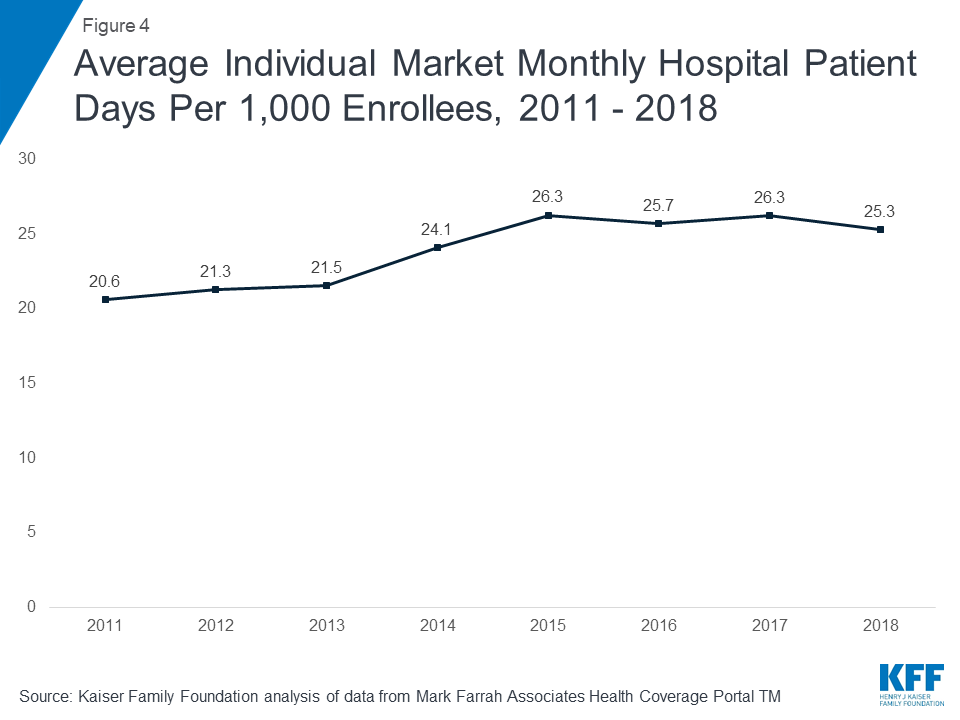

One concern about rising premiums in the individual market was whether healthy enrollees would drop out of the market in large numbers rather than pay higher rates. While the vast majority of exchange enrollees are subsidized and sheltered from paying premium increases, those enrolling off-exchange would have to pay the full increase. Despite this dynamic, the average number of days individual market enrollees spent in a hospital in 2018 was slightly lower than inpatient days in the previous three years.2

Taken together, these data on claims and utilization suggest that the individual market risk pool is relatively stable, though sicker on average than the pre-ACA market, which is to be expected since people with pre-existing conditions have guaranteed access to coverage under the ACA. Despite concerns that healthier enrollees may be dropping out of the market in recent years, somewhat lower average inpatient days indicate that the individual market did not get sicker, on average, during 2018.

Expected Rebates

The medical loss ratio (“MLR”) provision of the ACA requires most insurance companies that cover individuals to spend at least 80% of their premium income on health care claims and quality improvement, leaving the remaining 20% for administration, marketing, and profit. Beginning in 2012, insurers failing to meet the applicable MLR standard for the prior year (2011) were required to issue rebates to consumers and employers. Thus far, the 2011 rebates had remained the largest ever issued – totaling $399 million in the individual market alone (and $1.071 billion across the individual, small group, and large group markets).

Insurers’ preliminary estimates indicate they expect to issue about $800 million in rebates to 2018 individual market enrollees, which would be the highest total for the individual market by far since the program began. While this represents initial insurer estimates, and the actual rebate amount issued could be lower or higher3 , these high expected rebates provide further evidence that some insurers over-corrected in raising individual market premiums for 2018.

Insurers estimate more than 3 million 2018 individual market enrollees, or 26%, are eligible to receive rebates. Insurers owing rebates expect to issue about $260 per member, on average. All rebates must be issued by September 30 of the year following the applicable MLR reporting period (i.e., September 2019 for the 2018 reporting period).

Across all commercial markets – individual, small group, and large group – rebates are expected to total approximately $1.4 billion. If insurer estimates hold true, these will be the largest rebates issued since the MLR program began. These higher rebates are mostly driven by the individual market. Rebates in the small and large group markets are expected to be larger than average, but not significantly so.

Discussion

Annual results from 2018 suggest that despite significant challenges and recent enrollment declines, insurers in the individual insurance market are now generally profitable. Insurer financial results from 2018 – after the Administration’s decision to cease cost-sharing subsidy payments, but before the repeal of the individual mandate penalty in the tax overhaul went into effect – reveal the most favorable year in the ACA-compliant market’s history.

Premium and claims data support the notion that 2017 premium increases were necessary as a one-time market correction to adjust for a sicker-than-expected risk pool, and premium increases in 2018 were in large part compensating for policy uncertainty and the termination of cost-sharing subsidy payments, though some insurers appear to have over-compensated. Without these policy changes, it is likely that insurers would generally have required only modest premium increases in 2018. Low loss ratios and higher margins indicate that some insurers raised premiums more than was necessary to cover claims and administrative costs and earn a reasonable profit in 2018.

Across the individual market, insurers expect to pay record-high rebates to consumers for failing to meet the medical loss ratio requirement, providing further evidence that insurers over-corrected when setting 2018 premiums. Before the ACA’s MLR provision went into effect, insurers in such a situation would have experienced windfall profits. The MLR rule requires insurers to repay consumers in the form of a cash rebate or premium credit when the prior year’s premiums are determined to have been too high relative to claims costs.

While markets in some parts of the country remain more fragile, the individual market on average is becoming more profitable. Some insurers have exited the market in recent years, but others have been successful and expanded their footprints, as would be expected in a competitive marketplace. Even though repeal of the individual mandate penalty and expansion of loosely-regulated insurance options had an upward effect on 2019 premiums, premiums actually decreased slightly because 2018 premiums were higher than necessary to cover claims costs. In 2019, new insurers have entered and some insurers are reentering markets they had previously exited. While signups through the marketplace during the 2019 open enrollment period declined somewhat compared to 2018, financial results suggest the market is still stable and sustainable.

Methods

We analyzed insurer-reported financial data from Health Coverage Portal TM, a market database maintained by Mark Farrah Associates, which includes information from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The dataset analyzed in this report does not include NAIC plans licensed as life insurance or California HMOs regulated by California’s Department of Managed Health Care; in total, the plans in this dataset represent at least 80% of the individual market. All figures in this issue brief are for the individual health insurance market as a whole, which includes major medical insurance plans and mini-med plans sold both on and off exchange. We excluded some plans that filed negative enrollment, premiums, or claims and corrected for plans that did not file “member months” in the annual statement but did file current year membership.

To calculate the weighted average loss ratio across the individual market, we divided the market-wide sum of total incurred claims by the sum of all unadjusted health premiums earned. Medical loss ratios in this analysis are simple loss ratios and do not adjust for quality improvement expenses, taxes, or risk program payments. Gross margins were calculated by subtracting the sum of total incurred claims from the sum of unadjusted health premiums earned and dividing by the total number of member months (average monthly enrollment) in the individual insurance market. Using earned premiums adjusted for taxes and fees to calculate loss ratios and gross margins increases the MLR by 6 percentage points and decreases the gross margin per member by $42 in 2018. On average across all years, using earned premiums adjusted for taxes and fees increases the MLR by 3 percentage points and decreases the gross margin per member by $14.

Total rebates are based on preliminary estimates from insurers. Since 2014, the total rebate amount issued across the individual, small group and large group markets has varied by 3 to 5% from insurer estimates. At the market level, the difference between estimates and actual rebate totals have been more volatile. Since 2014, individual market estimates have varied by as much as $34 million, or over 20%, as compared to the final actual rebates reported in December of the year following the applicable MLR reporting period. In some years, final rebates are higher than expected and in other years, final rebates are lower.

Endnotes

- The loss ratios shown in this issue brief differ from the definition of MLR in the ACA, which makes some adjustments for quality improvement and taxes, and do not account for reinsurance, risk corridors, or risk adjustment payments. Reinsurance payments, in particular, helped offset some losses insurers would have otherwise experienced. However, the ACA’s reinsurance program was temporary, ending in 2016, so loss ratio calculations excluding reinsurance payments are a good indicator of financial stability going forward. ↩︎

- Hospital patient days for 2014 are not necessarily representative of the full year because open enrollment was longer that year and a number of exchange enrollees did not begin their coverage until mid-year 2014. ↩︎

- See Methods for more discussion on how insurer estimates tend to vary from actual rebate totals. ↩︎