A First Look at North Carolina’s Section 1115 Medicaid Waiver’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots

Executive Summary

Medicaid funds typically cannot be used to pay for non-medical interventions that target the social determinants of health. However, in October 2018, CMS approved North Carolina’s Section 1115 waiver which provides financing for a new pilot program, called “Healthy Opportunities Pilots,” to cover evidence-based non-medical services that address specific social needs linked to health/health outcomes. The pilots will address housing instability, transportation insecurity, food insecurity, and interpersonal violence and toxic stress for a limited number of high-need enrollees. This waiver differs from others recently approved by the Trump Administration that aim to address health determinants by conditioning coverage on meeting work requirements. The pilot program may yield important evidence about how addressing certain non-medical needs may impact program costs and health outcomes. However, the scope and impact of the program is restricted by its limited funding. Implementing a long-term program on a broader scale would require larger sustainable financing streams and it’s unclear at this point whether CMS will use this waiver as a model for other states. This brief summarizes key features of the Healthy Opportunities Pilots.

Healthy Opportunities Pilots Key Highlights

Funding – CMS authorized $650 million in Medicaid funding for the pilot over five years, $100 million of which will be available for capacity building.

Pilot area – will include two to four regions of the state and is expected to serve approximately 25,000 to 50,000 beneficiaries, or about 1% to 2% of total Medicaid enrollees in North Carolina.

Eligible beneficiaries – must be enrolled in a managed care plan and must have at least one physical or behavioral health risk factor and at least one social risk factor.

Pilot services – will include evidence-based enhanced case management and other services, which must be approved by CMS, to address enrollee needs related to housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal safety.

Health plans – will manage the pilot budget and, working in close collaboration with care managers, will determine enrollee eligibility and authorize the delivery of pilot services.

Lead Pilot Entities (LPEs) – will develop, contract with, and manage the network of human service organizations that will deliver pilot services.

Timeline – The state will release an RFP for LPEs by November 2019 and anticipates beginning to deliver pilot services in late 2020.

Issue Brief

Background

There has been growing recognition that although health care is essential to health many broader social and environmental factors play a major role in shaping health. Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.1 They include factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, nutrition/food security, and social support networks, as well as access to health care. In recent years, a broad range of initiatives have been launched at the federal, state, and local levels and by plans and providers to address social determinants of health, including efforts within Medicaid. These efforts stem from increasing rates of coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), new funding and demonstration authorities provided through the ACA, and an increasing shift across the health system toward value- or outcome-based payments and “whole person” care.

Under a new waiver, North Carolina’s Medicaid program will pay for non-medical interventions that address housing instability, transportation insecurity, food insecurity and interpersonal violence & toxic stress for a limited number of high-need enrollees

Within Medicaid, states can use a range of optional state plan and waiver authorities (e.g., 1915(i), 1915(c), or Section 1115) to add certain non-clinical services to the Medicaid benefit package including case management, housing supports, employment supports, and peer support services for people who need help with self-care or household activities as a result of disability or chronic illness. Generally, states have not been able to use federal Medicaid funds to pay the direct costs of non-medical services like housing and food. Under federal Medicaid managed care rules, managed care plans have some limited flexibility to pay for non-medical services.2 Additionally, other recent Medicaid payment and delivery system reforms, like the formation of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), may provide flexibility or opportunities to cover non-medical services that support health.

Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers provide states an avenue to test new approaches in Medicaid that differ from what is allowed by federal statute. States can obtain approval for Section 1115 demonstration waivers that test broad changes in Medicaid eligibility, benefits and cost-sharing, and payment and delivery systems as long as the Secretary determines that the demonstration is furthering the objectives of the Medicaid program. Waivers generally reflect priorities identified by states and CMS and often reflect changing priorities from one administration to another.

The current administration has largely marked a new direction for Medicaid demonstration waivers, including the approval of waivers that condition Medicaid eligibility on meeting work and reporting requirements as well as the approval of other policies that restrict eligibility and enrollment. In its approval of these demonstrations, the administration asserts such policies are designed to address health determinants (like employment) and to ultimately improve health outcomes.3 These new waivers run counter to many other efforts to address social determinants of health that focus on identifying social needs and facilitating links to services rather than making individuals’ health coverage dependent on meeting certain requirements – like reporting minimum monthly work hours.

CMS’s approval of North Carolina’s enhanced case management pilots within the state’s new Medicaid managed care delivery system stands in contrast to this recent trend in waiver approvals. This waiver allows the state to use Medicaid to pay directly for non-medical interventions that target the social determinants of health, although the program scope is restricted by its limited funding.

Overview of North Carolina’s Section 1115 Waiver

In 2015, the North Carolina General Assembly passed legislation that required the state’s Medicaid program to transition from its long-standing enhanced PCCM model to capitated managed care.4 Although the use of capitated managed care does not require Section 1115 waiver authority, as part of this transition, the state pursued certain elements, including an “Institution for Mental Disease” (IMD) waiver, pilots to address targeted health-related needs, a tribal uncompensated care pool, workforce innovation fund, and behavioral health home capacity-building funds which required submission of a Section 1115 waiver.5 ,6 In October 2018, CMS approved North Carolina’s Section 1115 waiver, including its transition from a fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid delivery system to a capitated managed care program. North Carolina aims to transition approximately 1.5 million of its 2 million Medicaid enrollees to the new managed care delivery system.7 The state will begin transitioning enrollees by region to managed care “standard” plans in November 2019. Standard plans will cover physical, behavioral health, and pharmacy benefits. In 2021, the state plans to launch “tailored” plans for enrollees that have more significant mental health, intellectual or developmental disabilities, substance use, and traumatic brain injury needs.8 The state will also add “specialized” plans for foster care youth and former foster care youth. The state will require health plans to contract with local care management entities, including advanced medical homes and local health departments.

Within the new Medicaid managed care delivery system and care management infrastructure, CMS also approved a Healthy Opportunities Pilot program. All health plans must implement standardized screening questions to assess enrollees’ non-medical needs. If unmet needs are identified, plans will connect beneficiaries to community resources. Plans will have access to a statewide tool – NCCARE360 – to identify community resources and track and monitor referrals.9 Beyond these statewide efforts, in select regions, the Healthy Opportunities Pilots will authorize the use Medicaid funds to pay for enhanced case management and other support services for certain high-risk enrollees that meet physical or behavioral health and social risk factor criteria. The program aims to reduce health care costs and improve health outcomes by providing services to address housing instability, transportation insecurity, food insecurity, and interpersonal violence and toxic stress. The program is the first of its kind approved by CMS, allowing Medicaid funds to be used to pay for non-medical interventions that target the social determinants of health. CMS authorized $650 million in Medicaid funding for the pilot over five years. Funding for the pilot is part of the broader Section 1115 waiver in which the state must demonstrate budget neutrality to the federal government – meaning federal costs under the waiver must not exceed what federal costs would have been for that state without the waiver.10

Key Features of the Healthy Opportunities Pilots

The state will operate the Healthy Opportunities Pilot program in two to four regions. Reflecting the program’s funding limitations, it expects to serve approximately 25,000 to 50,000 beneficiaries (or about 1% to 2% of total Medicaid enrollees) through the pilot program.

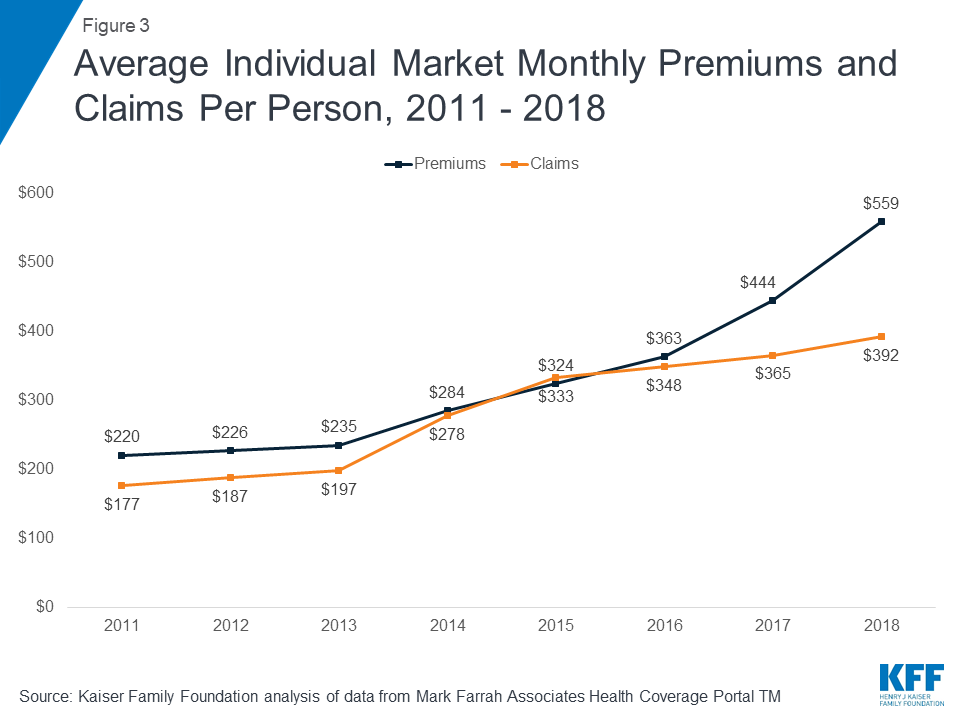

To be eligible to participate in the pilot program, beneficiaries must be enrolled in a managed care plan (standard, tailored, or a specialized plan) and must have at least one physical or behavioral health risk factor and at least one social risk factor (Figure 1). Health risk factors include adults with two or more chronic conditions or repeated emergency room use or hospital admissions; high-risk pregnant women (e.g., multifetal gestation, chronic condition likely to complicate pregnancy); and high-risk infants and children (e.g., prematurity, low birth weight, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, or one or more uncontrolled chronic conditions). Social risk factors include homelessness and housing insecurity, food insecurity, transportation insecurity, and being at-risk of witnessing or experiencing interpersonal violence. Participation in the pilot is voluntary and enrollees may opt out at any time.

Pilot services will include evidence-based enhanced case management and other services designed to address enrollee needs related to: housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal safety. For example, pilot services may include housing modifications (e.g., carpet replacement, air conditioner repair) to improve a child’s asthma control, travel vouchers to a community-based food pantry or a medically-targeted healthy food box for an adult with diabetes living in a rural food desert, or assistance securing safe housing for a pregnant woman experiencing interpersonal violence.11 The care manager will recommend pilot services at the lowest intensity level that can be reasonably expected to meet an individual’s needs. Pilot transportation services include non-emergency health-related transportation including transportation to social services or to access pilot services. (Transportation services under the pilot are in addition to the non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit states are required to provide which helps ensure Medicaid beneficiaries have transportation to and from medical providers.) Approved pilot services are outlined in the waiver special terms and conditions.12 Any changes to the pilot services list must be reviewed and approved by CMS. Currently approved pilot services are also broadly outlined in Figure 1 (see Appendix for additional detail).

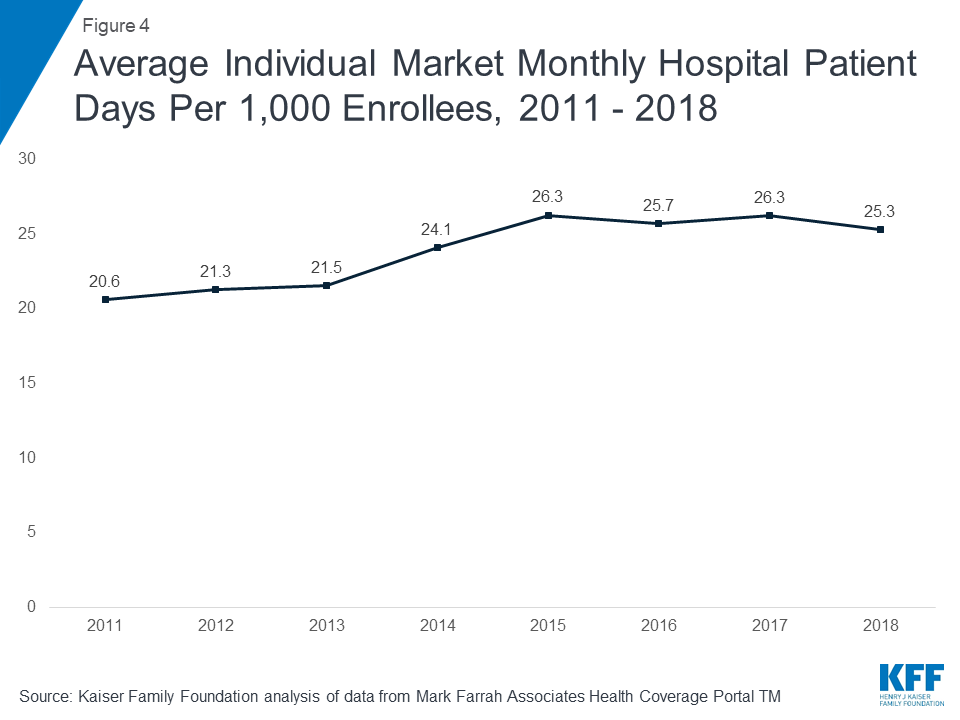

The state will require health plans to participate in the pilot program if they operate within any of the selected pilot regions. Health plans will be responsible for managing their pilot budget and may set enrollment caps/restrictions, if approved by the state – if/when the plan has limited funding capacity to serve all eligible enrollees (Figure 2). Health plans, in collaboration with care managers, will identify eligible enrollees and will seek consent from them to participate in the pilot program. Care managers will use standardized screening questions to assess health-related unmet resource needs.13 Health plans and their care managers will determine the pilot services to be provided to each enrollee and will work in collaboration with the lead pilot entity (LPE) to track enhanced case management and other pilot services. Every three months, health plans will review the pilot services each enrollee is receiving to ensure the services are meeting the enrollee’s needs. Plans must reassess enrollee pilot eligibility every six months. Health plans will also be required to participate in “learning communities” to disseminate best practices across regions.

Each region will have one lead pilot entity (LPE) that will serve as the regional pilot coordinator and will be accountable for pilot operations. The state will select LPEs through a competitive procurement process. The state expects LPEs to be rooted in their communities, indicating entities best positioned for this role may include, community-based organizations, county-based public agencies, local health departments, social services or multiservice agencies, community health centers, community health foundations, associations, or a partnership of agencies.14 The state expects LPEs will be “anchored by” a community-based health or social service organization and will not be led by a health system. LPEs will develop, contract with, and manage the network of participating pilot providers, including community-based organizations, social service agencies, and health care providers, that will deliver pilot services. LPEs will develop payment protocols and procedures and will track payments made to pilot providers. They will monitor and track pilot services and report on metrics for rapid cycle and summative evaluations. LPEs will provide technical assistance to health plans and providers and will participate in “learning communities.”

CMS authorized $650 million in federal and state Medicaid funding for the pilot over five years, $100 million of which will be available for capacity building. The state will distribute funding for the pilots to the participating health plans. Funding for each plan, which is outside of their capitation rate, will be a capped allocation based on the volume and cost of pilot services delivered to enrollees, including an administrative fee. Health plans will distribute funds to lead pilot entities. The LPEs will then distribute funds to providers authorized to deliver pilot services. The majority of pilot funding must be used to deliver pilot services. To ensure pilot funding is not used for a single domain (e.g., housing) or for a single population, the state plans to establish requirements regarding the minimum share of pilot funds that must be used for each of the four domains and across populations. LPEs may use capacity building funding to develop infrastructure/systems to prepare providers to deliver services, receive payment, and report on managing patient care. LPEs may also use capacity building funds for monitoring and program integrity purposes as well as for providing technical assistance. Federal financial participation (FFP) will be calculated based on aggregated amounts actually paid by the state to pilot providers, LPEs, and health plans.15

Pilot services will be reimbursed through two methods: fee-for-service/cost-based reimbursement and bundled payments. The state must develop and submit fee schedules, cost-based reimbursement service sets, and bundled payment fee schedules to CMS for review no later than July 1, 2019. Over the course of the demonstration, the state must incorporate value-based payments for pilot services, increasingly linking payments for pilot services to health outcomes. The state will incorporate incentive payments in demonstration years one and two, withholds in years three and four, and shared savings arrangements in year five.

The state must develop an evaluation design for the pilot program, and must use an independent evaluator to conduct a summative pilot program evaluation as well as rapid cycle assessments. The rapid cycle assessments will help the state identify which interventions are most and least effective, so the state can make any necessary mid-course adjustments. Evaluation activities will also help the state identify effective services to incorporate into managed care statewide after the pilot ends.

The state’s Section 1115 waiver was approved for a 5-year period from November 1, 2019 through October 31, 2024. The state will release a Request for Proposal (RFP) in two to four regions detailing roles and responsibilities for LPEs by November 1, 2019. The state anticipates that the pilots will begin delivering services in late 2020.16

Looking Ahead

CMS’s approval of North Carolina’s enhanced case management pilots within the state’s new Medicaid managed care delivery system is notable, as Medicaid funds typically cannot be used to pay directly for non-medical interventions that target the social determinants of health and as the Trump administration has been largely focused on more restrictive policies that may result in coverage loss, like work requirements, in its effort to help states address determinants of health and improve health outcomes. In contrast, the pilots approved in North Carolina will use coverage, and service provision, to support health-related needs. The pilot program may yield important evidence involving how addressing certain non-medical needs may impact program costs and health outcomes. However, the scope and impact of the program is restricted by its limited funding. Implementing a long-term program on a broader scale would require larger sustainable financing streams and it’s unclear at this point whether CMS will use this waiver as a model for other states. managed care delivery system is notable, as Medicaid funds typically cannot be used to pay directly for non-medical interventions that target the social determinants of health and as the Trump administration has been largely focused on more restrictive policies that may result in coverage loss, like work requirements, in its effort to help states address determinants of health and improve health outcomes. In contrast, the pilots approved in North Carolina will use coverage, and service provision, to support health-related needs. The pilot program may yield important evidence involving how addressing certain non-medical needs may impact program costs and health outcomes. However, the scope and impact of the program is restricted by its limited funding. Implementing a long-term program on a broader scale would require larger sustainable financing streams and it’s unclear at this point whether CMS will use this waiver as a model for other states.

Appendix

| Healthy Opportunities Pilot Services Examples | |

| Housing | Tenancy support and sustaining services

Housing quality and safety improvement services

Legal assistance

Securing housing payments

Short-term post-hospitalization

|

| Food | Food support services

Meal delivery services

|

| Transportation | Non-emergency health-related transportation

|

| Interpersonal Violence (IPV) / Toxic Stress | IPV-related transportation

IPV and parenting

Support resources

Legal assistance

Child-parent support

|

SOURCE: North Carolina’s Medicaid Reform Demonstration, approved October 19, 2018, see Attachment G.

Endnotes

- “About Social Determinants of Health,” World Health Organization, accessed March 22, 2019, http://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/. ↩︎

- Under federal Medicaid managed care rules, Medicaid MCOs may have flexibility to pay for non-medical services through “in-lieu-of” authority and/or “value-added” services. “In-lieu-of” services are a substitute for covered services and may qualify as a covered service for the purposes of capitation rate setting. “Value-added” services are extra services outside of covered contract services and do not qualify as a covered service for the purposes of capitation rate setting. ↩︎

- The federal court that’s ruled on this issue so far rejected the contention that the Secretary could focus on alternative criteria, including health and well-being, in approving the demonstration project, instead of the objective to promote affordable health coverage. See: https://ecf.dcd.uscourts.gov/cgi-bin/show_public_doc?2018cv1900-58. ↩︎

- Session Law 2015-245, General Assembly of North Carolina, Session 2015, http://www.ncleg.net/Sessions/2015/Bills/House/PDF/H372v8.pdf as amended by Session Law 2016-121, General Assembly of North Carolina, Session 2016, https://www.ncleg.net/EnactedLegislation/SessionLaws/HTML/2015-2016/SL2016-121.html. ↩︎

- North Carolina Amended 1115 Demonstration Application, submitted November 20, 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/nc/nc-medicaid-reform-pa2.pdf. ↩︎

- CMS did not approve a number of provisions requested by the state. The state notes that it will continue to negotiate the following waiver provisions with CMS: uncompensated care pool for tribal providers, workforce innovation fund, and behavioral health home capacity-building funds. See: https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/CMS-1115-Approval-FactSheet-FINAL-20181024.pdf. ↩︎

- North Carolina Amended 1115 Demonstration Application, submitted November 20, 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/nc/nc-medicaid-reform-pa2.pdf. ↩︎

- Prior to the implementation of BH I/DD tailored plans, BH I/DD qualified enrollees will remain in the FFS Medicaid system for physical health services and in the state’s 1915(b) program for BH I/DD services instead of being mandatorily enrolled in the “standard” plan. ↩︎

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots: A Review of Proposed Design for Interested Stakeholders, February 15, 2019, https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/documents/Healthy-Opportunities-Pilot_Policy-Paper_2_15_19.pdf. ↩︎

- For waiver budget neutrality purposes, pilot services are being treated as “hypothetical” – meaning, CMS considers these expenditures would have been eligible to receive FFP elsewhere in the Medicaid program (e.g., under section 1915 or under state plan authority). Subsequently, CMS does not require savings to offset these expenditures as part of the Section 1115 waiver. See: SMD # 18-009 Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects, August 22, 2018, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd18009.pdf. ↩︎

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots: A Review of Proposed Design for Interested Stakeholders, February 15, 2019, https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/documents/Healthy-Opportunities-Pilot_Policy-Paper_2_15_19.pdf. ↩︎

- North Carolina Medicaid Reform Demonstration (11-W00313/4), approved October 19, 2018, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/nc/nc-medicaid-reform-ca.pdf. ↩︎

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Using Standardized Social Determinants of Health Screening Questions to Identify and Assist Patients with Unmet Health-related Resource Needs in North Carolina, April 5, 2018, https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/documents/SDOH-Screening-Tool_Paper_FINAL_20180405.pdf. ↩︎

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots: A Review of Proposed Design for Interested Stakeholders, February 15, 2019, https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/documents/Healthy-Opportunities-Pilot_Policy-Paper_2_15_19.pdf. ↩︎

- For waiver budget neutrality purposes, pilot services are being treated as “hypothetical” – meaning, CMS considers these expenditures would have been eligible to receive FFP elsewhere in the Medicaid program (e.g., under section 1915 or under state plan authority). Subsequently, CMS does not require savings to offset these expenditures as part of the Section 1115 waiver. See: SMD # 18-009 Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects, August 22, 2018, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd18009.pdf. ↩︎

- NC Medicaid, Healthy Opportunities Pilots Fact Sheet, https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/SDOH-HealthyOpptys-FactSheet-FINAL-20181114.pdf. ↩︎