Introduction

Addressing health care needs of people moving into and out of the criminal justice system and staff who work with justice-involved individuals is an important component of coronavirus response efforts. Millions of people interact with the correctional system, including individuals moving into and out of jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers, as well as staff, health care workers, vendors, and visitors. Given the close quarters and shared spaces within correctional facilities, coronavirus and other infectious diseases may spread easily among individuals who interact with correctional system and extend into the broader communities in which facilities are located, including through transmission through workers and visitors. Further, justice-involved individuals are at increased risk for experiencing complications from coronavirus due to high rates of underlying health conditions. This brief provides an overview of health risks for the justice-involved population, discusses the role Medicaid can play in response efforts for justice-involved individuals, and identifies other steps states and localities can take to mitigate risk and spread of coronavirus among this population to protect and promote public health.

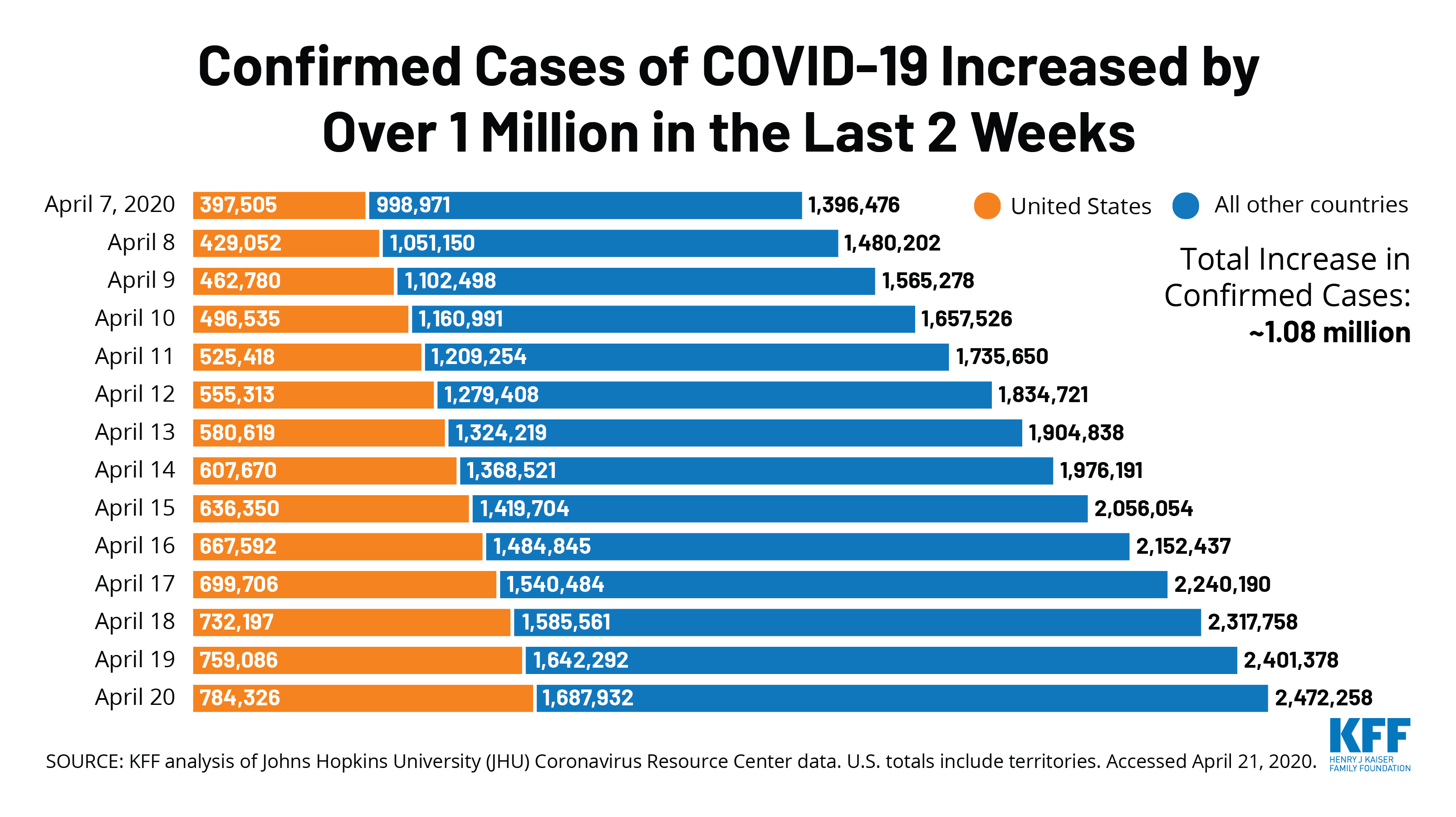

Data on Coronavirus Cases and Deaths

Data show confirmed coronavirus cases within federal and state correctional facilities and immigration detention centers. As of April 14, 2020, there were 694 confirmed coronavirus cases in the nation’s federal prisons, including 446 incarcerated individuals and 248 staff as well as 14 reported deaths among federal inmates.9 Comprehensive data is not available for state and local correctional systems. However, in New York City – one of the epicenters of the COVID-19 crisis – the Board of Correction reported two deaths and 961 confirmed cases of coronavirus among detained individuals (334 cases) and staff (627 cases) as of April 14, 2020.10 In Illinois, the Cook County Sherriff’s office reported three deaths and 323 confirmed cases of coronavirus among detained individuals, including 21 hospitalized individuals as of April 14, 2020.11 ICE reported 89 confirmed cases of coronavirus in detention centers operated or contracted by ICE, including local jails and prisons; 21 staff in ICE detention centers; and 80 staff that are not assigned to detention facilities as of April 14, 2020.12

The Justice-Involved Population

The criminal justice system is comprised of a range of different types of correctional facilities. Correctional facilities include prisons, which typically house longer-term felons or inmates serving a sentence of more than one year, and jails, which house individuals awaiting trial or sentencing and those convicted of misdemeanors and serving shorter terms that are typically less than one year. In addition, juvenile justice facilities house youth who have been convicted of offenses or who have not responded to intermediate sanctions. There also are several forms of community-based corrections, including probation, parole, and halfway houses. The federal government and states oversee prisons, while local cities or counties typically govern jails. There are over 3,200 jails nationwide housing individuals awaiting trial or serving a short sentence for a misdemeanor.13

About 2.2 million individuals are incarcerated in prison or jail each year, but millions more interact with the correctional system annually.14 Approximately 1.5 million individuals were incarcerated in prisons as of the end of 2016.15 Over the course of the year, about 600,000 individuals are admitted to prison and a similar number are released.16 As of midyear 2017, approximately 745,000 individuals were held in jails.17 About six in ten (65%) jail inmates were not convicted and awaiting court action; the remaining nearly four in ten (35%) were sentenced or convicted offenders awaiting sentencing.18 Given the shorter terms of jail inmates compared to prisoners, there is rapid churn among the jail population. Between July 2016 and June 2017, an estimated 10.6 million people were admitted to local jails and, on average, jails experienced a weekly turnover rate of 54%.19 The jail population is largely concentrated in large jails (that have an average daily population of 1,000 or more inmates), which house more than four in ten (43%) jail inmates but only account for 5% of all jail jurisdictions.20 In addition to individuals incarcerated in prisons and jails, there were an estimated 423,000 correctional officers nationwide as of May 2019.21 An additional 4.5 million adults were under community supervision as of the end of 2016, and there were roughly 5 million entries to and exits from community supervision over the course of 2016.22 About 80% of adults under community supervision are on probation, while the remainder are on parole.23

| Table 1: Overview of the Criminal Justice-Involved Population |

| Prisoners |

| Number of Prisoners as of December 31, 2017 | 1,489,400 |

| Number of Admissions of Sentenced Prisoners during 2017 | 606,600 |

| Number of Releases of Sentenced Prisoners during 2017 | 622,400 |

| Jail Inmates |

| Number of Inmates in Local Jails as of June 2017 | 745,200 |

| Number of Persons Admitted to Local Jails, July 2016-June 2017 | 10,600,000 |

| Weekly Turnover Rate, week ending June 30, 2017 | 54% |

| Adults Under Community Supervision |

| Number Under Community Supervision as of December 31, 2016 | 4,537,100 |

| Number Entering Community Supervision during 2016 | 2,469,300 |

| Number Exiting Community Supervision during 2016 | 2,527,400 |

| Staff Working in Correctional Facilities |

| Number of Correctional Officers and Jailers, as of May 2019 | 423,100 |

| SOURCES: Danielle Kaeble, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2016, (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, April 2019); and Jennifer Bronson and E. Ann Carson, Prisoners in 2017, (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, April 2019); and Zhen Zeng, Jail Inmates in 2017 (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, April 2019); and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2019, 33-3012 Correctional Officers and Jailers.” Last updated April 3, 2019, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics). |

ICE manages and oversees the nation’s civil immigration detention system, detaining individuals who are awaiting the outcome of their immigration cases or pending removal. People in ICE custody are housed in a variety of facilities, including ICE-owned and operated facilities; local, county, or state facilities; and contractor-owned and operated facilities.24 Individuals held in ICE facilities include asylum seekers transferred from ports of entry, as well as community residents taken into custody by ICE in their homes, neighborhoods, or after an interaction with the criminal legal system. ICE uses dedicated facilities to house families with children who are going through immigration proceedings. ICE operates or contracts to operate over 200 detention facilities across the U.S. and, in fiscal year FY 2019, reported over 510,000 book-ins to those facilities, a 29% increase from the year prior.25 The average length of stay for individuals in detention was over a month (34.3 days). Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) detains individuals on a short-term basis to allow for initial processing but will then transfer individuals to other agencies like ICE.26

Health Risks for Justice-Involved Population

Coronavirus and other infectious diseases may spread easily among individuals who interact with correctional system given the close quarters and shared spaces within correctional facilities. Incarcerated individuals live in close contact with other individuals, including shared cells and shared living spaces, such as laundry and eating areas. Moreover, transmission can occur between facilities and the community in which they are located given that many individuals, such as staff and visitors, move into and out of facilities on a daily basis and the very high turnover rate in jails. Deficiencies in medical and hygiene practices within correctional facilities and immigration centers may also exacerbate risks of transmission. For example, previous research has found previous outbreaks of infectious diseases in ICE detention centers, reflecting conditions in the facilities.27 Research also shows that, although correctional facilities and immigration detention centers are required to provide health care services, many individuals detained in these facilities go without needed care, receive inadequate or delayed care, or experience living conditions that present health risks, such as mold and unusable toilets.28

People in jails and prisons are at risk for experiencing complications from coronavirus due to high rates of underlying health conditions. Chronic disease is prevalent among the population with higher rates of tuberculosis, asthma, diabetes, hypertension, HIV, hepatitis, stroke, and sexually transmitted disease compared to the general population.29 They also have significant behavioral health needs. Over half of prison and jail inmates have a mental health disorder, with local jail inmates experiencing the highest rate (64%).30 Moreover, the majority of inmates with a mental health disorder also have a substance or alcohol use disorder.31

Individuals moving into and out of the criminal justice system also face a variety of social challenges that are associated with poorer health and increased barriers to accessing health care. Poverty, unemployment, lower education levels, housing instability, and homelessness are all more prevalent issues among criminal justice-involved population than the general population.32 This population also generally has higher rates of learning disabilities and lower rates of literacy.33 Moreover, there are stark variations in incarceration rates by race and ethnicity. For example, the state imprisonment rate among Black adults is nearly six times the rate for White adults and Blacks and Hispanics represent disproportionately higher shares of the sentenced prison population compared to their share of the total adult population.34 Data suggest that communities of color are at higher risk for health and economic challenges associated with COVID-19 and early data suggest that groups of color are experiencing disproportionately high rates of infection and death.35

Role of Medicaid

Access to Medicaid for justice-involved individuals varies across states depending on whether they have adopted the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults. In the 37 states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion, nearly all adults with incomes up to 138% FPL ($17,609 for an individual as of 2020) are eligible for Medicaid. Eligibility for adults remains very limited in the remaining 14 states, where parent eligibility levels are often limited to less than half the poverty level and adults without dependent children generally are not eligible regardless of their income.

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, Medicaid coverage will be important for covering costs of inpatient hospital care provided to incarcerated individuals and for facilitating access care for individuals upon release. Current rules allow individuals to be enrolled in Medicaid while incarcerated, but Medicaid reimbursement for incarcerated individuals is limited to inpatient care provided at facilities that meet certain requirements. States can facilitate access to Medicaid coverage for people moving into and out of incarceration by suspending rather than terminating Medicaid coverage for enrollees who become incarcerated, which over 40 states reported doing as of January 2019.36 Suspending eligibility expedites access to federal Medicaid funds if an individual receives inpatient care while incarcerated, which will be of increasing importance if inpatient care needs grow due to coronavirus. Suspending Medicaid coverage also allows individuals to have their coverage active immediately upon release, facilitating access to health care services in the community. In addition, some states take steps to enroll uninsured individuals into Medicaid and connect individuals to care in the community prior to release, which is particularly important for maintaining treatment and continuity of care for people with substance use disorder.37

Some states are seeking waiver authority to expand the scope of services provided to incarcerated individuals that can qualify for Medicaid reimbursement as part of coronavirus response efforts. Section 1115 waivers allow states to test new approaches in Medicaid that differ from federal rules if they promote the objectives of the Medicaid program. Illinois has submitted a Section 1115 waiver to allow the state to claim federal Medicaid matching funds for the testing, diagnosis, and treatment of COVID-19 or other services provided in jails and prisons, and California has submitted a waiver proposal to allow for Medicaid coverage of testing and treatment.38 In addition, South Carolina has submitted a Section 1115 waiver request to allow for federal matching funds for inpatient care provided to incarcerated individuals by a correctional facility.39 Because South Carolina has not adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, few adults in facilities will likely qualify for Medicaid-covered services. CMS has not previously waived the inmate exclusion, and the proposed waivers would not address issues related to whether services provided in correctional facilities meet other Medicaid standards, for example, related to quality, transparency, and infrastructure. States can also obtain Section 1135 waivers to waive certain Medicaid requirements during a national emergency, which has been declared due to COVID-19. States could pursue Section 1135 waivers to allow for greater flexibility over requirements that facilities must meet to receive Medicaid reimbursement for inpatient care, for example, to allow reimbursement for emergency facilities that primarily serve justice-involved individuals or to house justice-involved individuals within a single unit within a health care facility. This could help ensure care for people involved in the justice system while minimizing burdens on local hospitals serving the broader community and reduce correctional staff needs by eliminating requirements for one-to-one staff management requirements that are otherwise required for individuals in an inpatient setting.40

Other Actions to Mitigate Risk

Correctional systems can take a range of other steps to mitigate risks of coronavirus among justice-involved individuals to protect and promote public health. For example, correctional facilities can reduce admissions, increase the number of people released from jails and prisons, and reduce unnecessary contacts within facilities, as described below. While these steps can help mitigate risks within facilities, individuals may face an array of challenges upon re-entry into the community, which may leave them at high risk for health, social, and economic challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic.41

- Some state and local correctional systems have implemented policies to reduce the number of people entering into facilities. For example, several governors have issued executive orders to limit admissions into jails and prisons. In Alabama, the governor issued a proclamation to provide police officers discretion to issue a summons of complaint in lieu of arrest for minor crimes; California’s governor issued an order to temporarily halt the intake and/or transfer of inmates and youth in the state’s prisons and youth correctional facilities; and the governor in Illinois issued an order to suspend all admissions from county jails. Other examples include Jails in King County, Washington, which are no longer accepting people brought in for misdemeanors that do not pose a serious public safety concern, and Maine releasing over 12,000 bench warrants for outstanding fines.42

- The federal government and some state and local correctional systems have also taken some steps to release detained individuals.43 In early April, Attorney General William Barr instructed the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to maximize the use of home confinement for federal prisoners while prioritizing the hardest hit facilities and public safety.44 ,45 Following the Attorney General’s memo, the BOP has placed 566 inmates on home confinement.46 In addition, several governors have taken action to increase the number of people eligible for release from prison or jail. For example, governors in New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, and Pennsylvania have directed correctional systems to take steps focused on releasing individuals who are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Other local jail systems and some state departments of corrections also have taken steps to release detained individuals, with most efforts targeted on release of nonviolent, low-level offenders (Box 1).47

Box 1: Examples of Actions to Release People from Incarceration

California is preparing to expedite the release of up to 3,500 inmates from state prisons who have less than 60 days left on their sentence and were convicted of non-violent offenses.48

New Jersey plans to release 1,000 inmates from jails who are serving sentences for probation violations, municipal court convictions, low-level crimes, and disorderly persons offenses.49

The Iowa Department of Corrections has expedited the release of 700 inmates who were previously determined to be eligible for parole. Other states, including Illinois, Colorado, and North Dakota, have taken steps to expedite or ease restrictions for granting parole.50 ,51

Los Angeles County released approximately 1,700 inmates from local jails, or roughly 10% of the inmate population. All had been convicted of non-violent crimes and had less than 30 days left on their sentences.52

New York City is also considering all inmates who are older or have a high-risk preexisting condition for release on a case-by-case basis, and has so far released 900 inmates.53 ,54 ,55

- All 50 states have implemented some form of restriction on visitation to correctional facilities, with 15 states suspending all visitation and 37 states suspending all visitation except for legal visits.56

Outside of facilities, courts can grant extensions on deadlines and suspend in-person proceedings and law enforcement agencies can limit arrests and/or expand citation in lieu of arrest policies. For individuals under community supervision, agencies can suspend all in-person reporting and check-ins, lengthen reporting periods, and or allow people to connect remotely. Supervision agencies could also recommend early termination of supervision and/or suspend incarceration for noncompliance with supervision terms.

Similarly, ICE has authority to curtail civil immigration enforcement and release individuals from custody to minimize public health risks of coronavirus. ICE reported that, as of March 18, 2020, it would focus enforcement activities on public-safety risks and individuals subject to mandatory detention based on criminal grounds.57 ICE also reiterated that, under existing policy, it will not carry out enforcement operations at or near health care facilities except in the most extraordinary of circumstances and that individuals should not avoid seeking medical care because they fear civil immigration enforcement. However, following the March 18th announcement, Administration officials indicated that they will continue enforcement actions and that those actions would not be limited to individuals convicted of a crime or who pose a threat to public safety.58 Also, although ICE has an existing policy of not carrying out enforcement actions at or near health care facilities, some individuals still may forego accessing health care services, including testing for coronavirus, due to fear. Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, research documented elevated fears of accessing health care and other services due to the current immigration policy environment.59 ICE reports that it is screening individuals in detention for coronavirus and is housing individuals at risk for spreading coronavirus separately from the general population. ICE also has suspended social visitation in all detention facilities.60 However, to date, it has taken limited steps to release individuals from detention facilities. A federal judge recently ordered ICE to release ten detained immigrants due to risks of contracting coronavirus and medical experts and civil rights groups have called for broader release actions.61 As of early April, media accounts report that ICE has identified 600 individuals held in detention for possible release because they are deemed as vulnerable to coronavirus and that 160 have already been released for these reasons. As of April 11, 2020, ICE reported holding 32,309 individuals held in detention.62