KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Parents and the Pandemic

Findings

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project tracking the public’s attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and qualitative research, this project tracks the dynamic nature of public opinion as vaccine development and distribution unfold, including vaccine confidence and acceptance, information needs, trusted messengers and messages, as well as the public’s experiences with vaccination.

Key Findings

- As children around the country head back to school, nearly half of parents of children ages 12-17, the age group currently eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, say their child has already been vaccinated (41%) or they will get the vaccine right away (6%). The vaccination status of children closely mirrors that of parents, with larger shares of older parents, Democrats, those with higher incomes and college degrees (all demographic groups with higher vaccine rates among adults), saying their child is vaccinated compared with their counterparts. Nearly four in ten Republican parents (37%) and half of parents who are unvaccinated themselves say they will “definitely not” get their 12-17 year-old vaccinated.

- Parents of younger children who are not yet eligible to be vaccinated continue to take a cautious approach to COVID-19 vaccines, with four in ten parents of children under 12 saying that once a vaccine is authorized for their child’s age group they will “wait a while to see how it is working” before getting their child vaccinated. About half of parents, regardless of their child’s age, say they are very or somewhat worried about their child getting seriously sick from coronavirus.

- For parents of unvaccinated teens, their top concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine center around the potential for long-term or serious side effects in children. However, we also find that as surveys of adults have identified, Hispanic and Black parents are more likely than White parents to cite concerns that reflect access barriers to vaccination, including not being able to get the vaccine from a trusted place, believing they may have to pay an out-of-pocket cost, or difficulty traveling to a vaccination site. A larger share of Hispanic parents than White parents also reports being concerned about needing to take time off work to get their child vaccinated.

- Few working parents – particularly those with lower incomes – say their employer offers them paid time off to get their children vaccinated or care for them if they experience vaccine side effects. One quarter of working parents of unvaccinated 12-17 year-olds say they would be more likely to get their child vaccinated if their employer offered them paid time off to do so.

- Four in ten parents of children ages 12-17 say their teen’s school provided information about COVID-19 vaccines for children or encouraged parents to get their children vaccinated. Those who say their school did either one of these things are more likely to say their child has received a COVID-19 vaccine than parents who say their school did not do these things, even after controlling for other demographic factors associated with higher vaccination rates, suggesting that schools could play a role in increasing vaccine uptake among 12-17 year-olds.

- A majority (58%) of parents of 12-17 year-olds say their child’s school should not require students to be vaccinated for COVID-19, and a similar share (54%) of parents of all school-age children say schools should not require vaccination even once the FDA has fully approved the use of a COVID-19 vaccine in children. Majorities of Democrats and parents of children who are already vaccinated support schools requiring vaccinations in both scenarios, while majorities of Republican parents and those whose children are unvaccinated are opposed.

- More than six in ten (63%) of all parents of children who attend school think their child’s school should require unvaccinated students and staff to wear masks at school, although most Republican parents (69%) oppose such a requirement and parents of unvaccinated children are evenly divided.

- Pediatricians continue to be a top trusted source of information on COVID-19 and kids, though most parents have not yet talked to their child’s pediatrician about the vaccine. Among parents of teens who discussed the vaccine with their pediatrician, most say the doctor recommended their child get vaccinated, and three-quarters of those whose pediatrician recommended vaccination say their child has received at least one shot.

- A majority of parents say they have talked about the COVID-19 vaccines with their 12-17 year-olds, including almost half who say they have discussed the vaccines “a lot.” Among parents of unvaccinated teens, four in ten say their child has expressed concerns about getting a COVID-19 vaccine and 12% say their child has said that they want to be vaccinated.

Parents and COVID-19 Vaccines

COVID-19 Vaccination Status of Parents

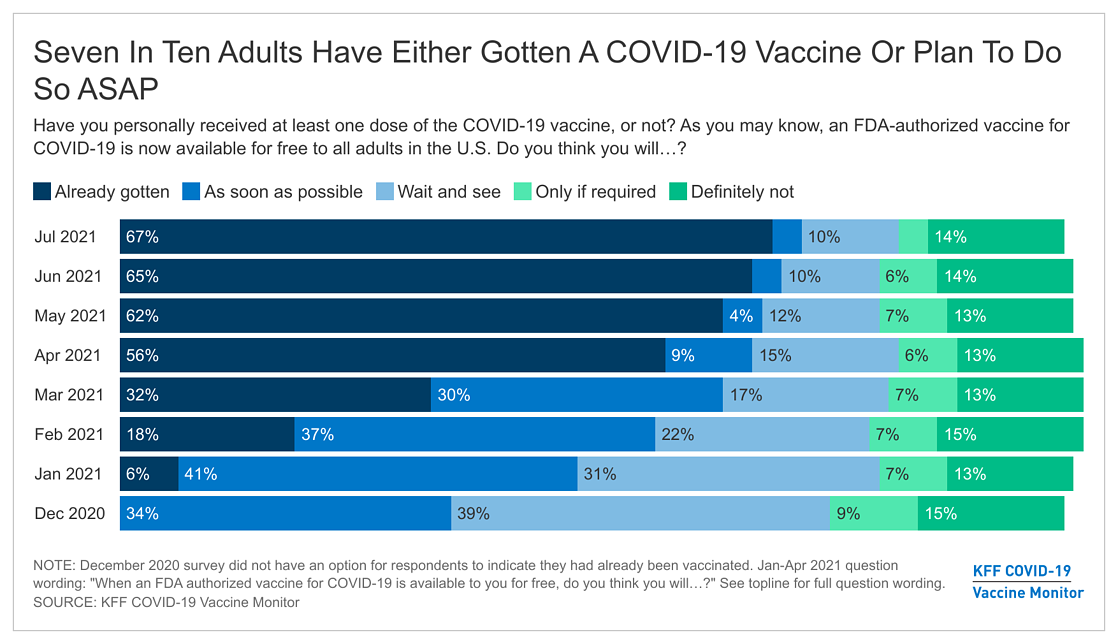

One way for parents to protect their children from the risk of COVID-19 is to get vaccinated themselves. The latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds 61% of parents say they have personally received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, which is somewhat lower than the 71% among adults without children (largely due to the fact that parents are younger on average than non-parents).

Among parents, some groups stand out as having lower vaccination rates than others, largely reflecting differences seen among the general population. For example, about half of those without health insurance (56%), Republican parents (54%), those with incomes under $40,000 per year (53%), parents ages 18-39 (50%), those without a college degree (49%), and Black parents (46%) say they have not received a COVID-19 vaccine.

Vaccination Intentions Among Parents Of Children Currently Eligible For COVID-19 Vaccination

Among parents of children ages 12-17, for whom the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine is currently authorized, 41% now say their child has received at least one dose of a vaccine, up from 34% in June1 . An additional 6% of parents of 12-17 year-olds say they intend to get their child vaccinated “right away.” Nearly one quarter of parents (23%) say they want to “wait and see” how the vaccine is working before getting their adolescent child vaccinated, while one in ten (9%) say they will only get their child vaccinated “if their school requires it,” and one in five say they will “definitely not” vaccinate their child.

Not surprisingly, parents’ vaccination intentions for their children are largely correlated with their own vaccination status. Six in ten parents who have received the vaccine themselves say their 12-17 year-old is vaccinated, compared to just 4% of unvaccinated parents. Among parents who have not been vaccinated themselves, half say they will “definitely not” vaccinate their child.

Besides vaccination status, parents’ vaccination intentions for their children differ along similar lines as adults overall. Parents who identify as Democrats, older parents, and those with higher levels of income and education are more likely to say their child is already vaccinated or they will get them vaccinated right away. Notably, nearly four in ten (37%) Republican parents say they will “definitely not” get their 12-17 year-old vaccinated.

While there have been gaps in COVID-19 vaccine uptake among adults by race and ethnicity, the current survey does not find a statistically significant difference in child vaccination uptake between Hispanic, Black, and White parents. However, White parents of children ages 12-17 are twice as likely as Hispanic parents to say they will “definitely not” get their child vaccinated (24% vs. 12%).

Parents’ intentions towards the COVID-19 vaccine for 12-17 year-olds are not necessarily a reflection of their behaviors with regards to other childhood vaccines. The vast majority of parents (90%) say they normally keep their children up-to-date with recommended vaccines such as the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, while just 9% say they have delayed or skipped some childhood vaccines for their children. Yet even among parents of 12-17 year-olds who say their children are up-to-date on other childhood vaccines, fewer than half (43%) say their child has received a COVID-19 vaccine. (The sample of parents of 12-17 year-olds who have skipped or delayed other vaccines is too small for analysis.)

Just over half of parents (54%) say their child normally gets a flu vaccine each year. Among parents of 12-17 year-olds who say their child normally gets a flu shot, 57% say their adolescent has received a COVID-19 vaccine, which is twice the share of parents who say their child does not normally get a flu vaccine who have gotten the COVID-19 vaccine (25%).

Vaccination Intentions Among Parents Of Younger Children

While uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among 12-17 year-olds has increased over time, parents continue to report a more cautious attitude when it comes to vaccinations for children younger than 12. About a quarter (26%) of parents of children between the ages of 5-11 say they will vaccinate their child “right away” once a vaccine is authorized for their age group, as do one in five parents with children under 5. Four in ten parents in each age group say they will “wait and see” how the vaccine is working before having their younger child vaccinated. One-quarter say they will “definitely not” get their 5-11 year-old vaccinated and three in ten parents say the same about their children under age 5.

Parents’ Concerns and Reasons For Holding Off On Child COVID-19 Vaccinations

Parents of unvaccinated children ages 12-17 cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety and side effects at the top of the list. A large majority (88%) of these parents say they are “very” or “somewhat” concerned that not enough is known about the long-term effects of the COVID-19 vaccine in children, and nearly as many (79%) say they are concerned their child might experience serious side effects from the COVID-19 vaccine. Nearly three-quarters of parents of unvaccinated adolescents (73%) report being concerned that the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future, even though the CDC states there is “no evidence that any vaccines, including COVID-19 vaccines, cause female or male fertility problems.”2 Two-thirds of parents of unvaccinated adolescents (65%) say they are concerned that their child might be required to get the COVID-19 vaccine even if they don’t want them to.

Notably, parents whose teens are unvaccinated but who have received a COVID-19 vaccine themselves are somewhat less likely than unvaccinated parents to express concern that their child will experience serious vaccine side effects (70% vs. 86%), that the vaccine might impact their child’s future fertility (58% vs. 85%), and that they will be required to get the vaccine even if the parent doesn’t want them to (50% vs. 78%).

A smaller share of parents overall cite concerns that may reflect access barriers to getting a COVID-19 vaccine for their child, though many of these concerns are more prevalent among Hispanic and Black parents than they are among White parents. For example, half (49%) of Hispanic parents of unvaccinated adolescents are concerned they might need to take time off work to get their child vaccinated or care for them if they experience side effects, twice the share of White parents (24%) who express the same concern. Similarly, among parents of unvaccinated 12-17 year-olds, larger shares of Hispanic and Black parents compared to White parents are concerned that they won’t be able to get their child the vaccine at a place they trust, they might have to pay an out-of-pocket cost to get their child vaccinated, or they will have difficulty traveling to a vaccine site for their child.

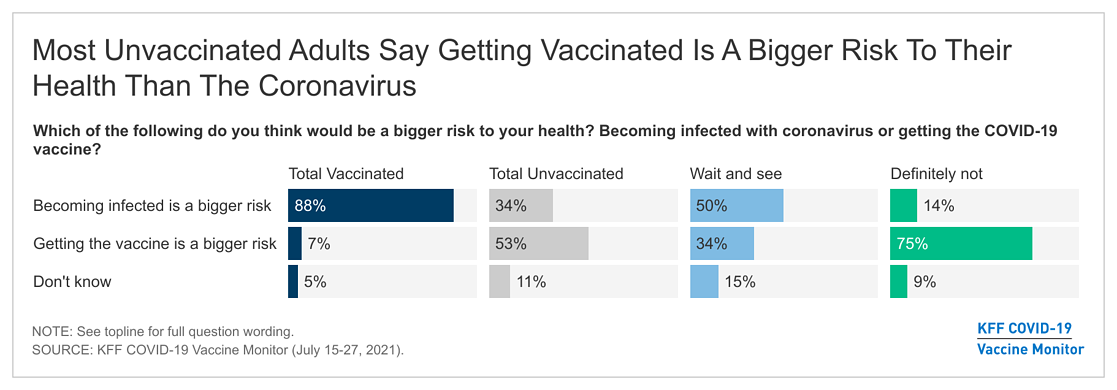

In addition to these concerns, many parents of unvaccinated 12-17 year-olds view the vaccine as a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting sick from COVID-19. Overall, six in ten (62%) parents of 12-17 year-olds say becoming infected with coronavirus is a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting the COVID-19 vaccine, while about half as many (34%) say getting the vaccine is a bigger risk. The share saying the vaccine is a bigger risk rises to 55% among Republican parents and 73% among parents who are unvaccinated themselves. Among parents of unvaccinated 12-17 year-olds, 55% say the vaccine is a bigger risk, including 91% of those who say they will “definitely not” get their child vaccinated.

When parents of adolescent children who have not yet been vaccinated are asked to name in their own words the main reason why their child has not received a COVID-19 vaccine, the top reasons include that not enough is known about the vaccines or wanting more research on the vaccines in children (19%), they are concerned about side effects (13%), their child does not want the vaccine (13%), they do not believe a vaccine is necessary (7%), and they don’t trust the vaccines (5%).

In their own words: What is the main reason your child has not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine?

Need more information/tests/research (19%)

“Because it's not been long enough to see what the long term effects are” – White father in Arkansas, will wait and see before getting child vaccinated

“Have not seen results reported on safety or effectiveness of this vaccine on children 12-17” – Hispanic father in California, will wait and see before getting child vaccinated

“Not enough information on how it affects children” – Black mother in Delaware, will wait and see before getting child vaccinated

“Because I feel as a parent this vaccine has not been tested enough…And my child is not a test dummy” – Black mother in Michigan, will definitely not get child vaccinated

“It is still experimental” – White father in North Dakota, will definitely not get child vaccinated

Side effects/reactions (13%)

“He was involved with summer school, and mom did not want side effects to interfere.” Hispanic mother in Alaska, will get child vaccinated right away

“Potential side effects outweigh risk of even contracting COVID” – White mother in Florida, will definitely not get child vaccinated

“I'm concerned about the short and longer term side effects” – Hispanic mother in Texas, will wait and see before getting child vaccinated

“Just concern it might be unhealthy for them. My oldest daughter got the Johnson & Johnson and then we found it there were issues about them.” – White mother in Washington, will wait and see before getting child vaccinated

Child doesn't want it/their choice (13%)

“She does not want it and her mother does not either” – Black father in Georgia, will only get child vaccinated if required

“I gave him a choice. He chose not to” – White mother in Idaho, will definitely not get child vaccinated

“I don't feel comfortable forcing him to get it since he is 17 and nearly an adult. I have strongly encouraged it though” – White mother in Wisconsin, will wait and see before getting child vaccinated

Not worried about COVID-19/Don't think vaccine is necessary (7%)

“Children in this age group are less at risk than vaccinated adults…Getting struck by lightning or winning the lottery are greater chances than death or serious illness from COVID in this age range” – Hispanic mother in Arizona, will definitely not get child vaccinated

“I haven't really been concerned about her getting the virus and she hasn't really been concerned about getting it” – White mother in Florida, will only get child vaccinated if required

“I think my child is healthy enough to battle the Covid-19 virus without a vaccine” – Hispanic mother in Georgia, will wait and see before getting child vaccinated

Don't trust the vaccine (5%)

“Too many that’s not trustworthy involved” – Black father in Arkansas, will definitely not get child vaccinated

“Don't trust the vaccine yet, need more info” – Hispanic mother in New York, will wait and see before getting child vaccinated

“Because I don't trust it” – White mother in Ohio, will definitely not get child vaccinated

Potential Role Of Employers In Facilitating COVID-19 Vaccinations For Children

Seven in ten parents of children under age 18 say they are employed, including six in ten who are employed full-time. More than a third of employed parents say their employer offers them paid time off to get a COVID-19 vaccine (39%) or to recover from side effects themselves (35%). However, most say their employer does not provide paid time off for them to get their children vaccinated (36%) or they are not sure if their employer offers this (42%). Similar shares say the same about paid time off to care for a child experiencing vaccine side effects.

Notably, parents with lower household incomes are even less likely than those earning higher incomes to say their employer provides paid time off for either their own vaccination and side effects or that of a child.

Among employed parents of unvaccinated 12-17 year-olds, one-quarter say they’d be more likely to get their child vaccinated if their employer gave them paid time off, while somewhat smaller shares of this group say they’d be more likely to vaccinate their child if their employer arranged for a medical provider to come to their workplace to vaccinate children and families (19%), or provided free transportation to a vaccine site (14%).

With lower rates of reported COVID-19 vaccination among parents with lower incomes, employer policies have the potential to reduce these income gaps somewhat. For example, just 29% of employed (non self-employed) parents with household incomes under $90,000 say their 12-17 year-old has been vaccinated for COVID-19 compared to over half (54%) of employed parents with higher incomes. Among employed parents with incomes under $90,000, an additional one in five say they’d be more likely to get their child vaccinated if their employer offered them paid time off, and some say they’d be more likely to vaccinate their child if their employer arranged for a medical provider to vaccinate children and families at their workplace (14%) or provided free transportation to a vaccination site (12%).

Parents’ Worries About Kids and COVID-19

While research has shown that children are less likely than adults to become seriously ill from coronavirus infection, parents may nevertheless worry about their children being exposed or passing an infection on to other family members, particularly when it comes to children under the ages of 12 who are not eligible for COVID-19 vaccination. The latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor reports that about half of parents of children ages 12-17 (48%) and under age 12 (52%) say they are worried about their child getting seriously ill from coronavirus. Similarly, about half of parents across child age groups say they are worried about their child being exposed to coronavirus and passing it on to family members or that they may personally be exposed to coronavirus and pass it on to their child.

Across child age groups, Black and Hispanic parents are much more likely than White parents to say they are worried about personally getting sick, about their child getting sick, about their child infecting someone else in the family, and about personally passing an infection on to their child. For example, among parents of children ages 12-17, 71% of Hispanic parents and 64% of Black parents are worried about their child getting seriously sick from coronavirus compared to 38% of White parents.

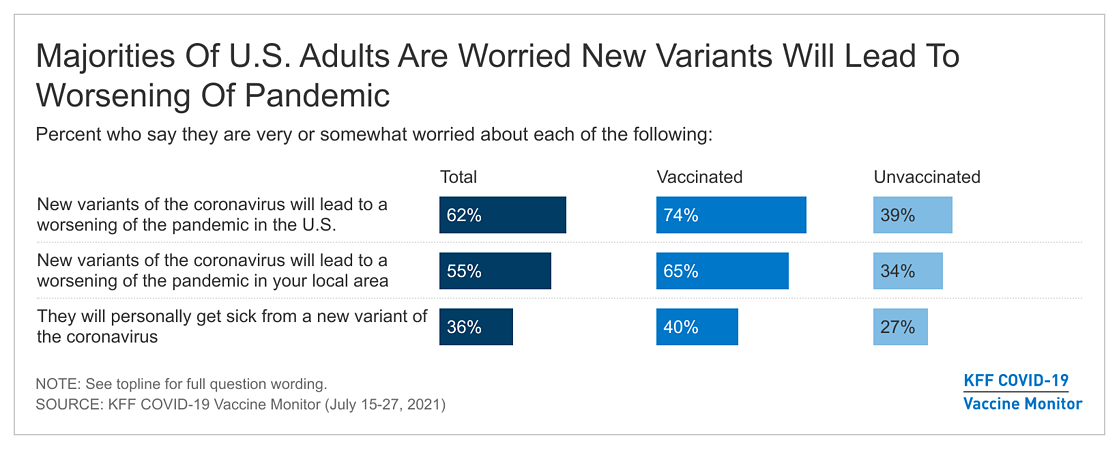

The July KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor found that despite being at higher risk for contracting the disease, unvaccinated adults are less likely than vaccinated adults to worry about getting sick from COVID-19. A similar pattern holds among parents. Parents of vaccinated children ages 12-17 are more likely than parents of unvaccinated children in this age range to worry about their child getting seriously sick from coronavirus (56% vs. 42%) and about their child becoming infected and passing the virus on to someone else in their family (60% vs. 44%).

Schools and COVID-19 Vaccines

With some schools around the country already open for the 2021-2022 school year and many others set to open later this month, this Vaccine Monitor report examines parents’ views on vaccines and other protective measures in their children’s schools. We find that while most parents of school-age kids say their children attended school at least partially online during the previous school year, a large majority expect school to happen all or mostly in person during the upcoming school year (87% of parents of 12-17 year-olds and 89% of parents of 5-11 year-olds).

Among parents of children ages 12-17 who are enrolled in school for the upcoming school year, about four in ten (42%) say the school has provided them with information about how to get a COVID-19 vaccine for their child and a similar share (40%) say the school has encouraged parents to get their children vaccinated. Higher-income parents are more likely than those with lower incomes to say their child’s school did either of these things; about half of parents with household incomes of $90,000 or more say their child’s school provided vaccine information or encouraged vaccination compared to between one-third and four in ten among parents with lower incomes.

Fewer parents of 12-17 year-olds say their child’s school asked about their child’s COVID-19 vaccination status (11%) or said that they will require students to be vaccinated in order to return to school in-person (7%).

Parents of 12-17 year-olds who say their child’s school provided information about COVID-19 vaccination are more likely than those whose school did not provide information to say their child has received a COVID-19 vaccine (58% vs. 32%). Similarly, about twice as many parents whose school encouraged vaccination report that their child is vaccinated compared to those whose schools did not (62% vs. 30%).

These differences may be at least partially due to differences in other demographic characteristics of parents whose schools provided information or encouraged vaccination compared to those who did not. However, using a statistical technique called multiple logistic regression, we find that parents whose children’s schools provided information or encouraged vaccination are more likely to say their child is vaccinated, even after controlling for demographic characteristics associated with child vaccination, including parents’ own vaccination status, age, race, ethnicity, education, income, party identification, urbanicity, and region. This suggests that more schools providing information and encouraging COVID-19 vaccination could contribute to higher vaccination rates among students.

Overall, most parents of children in the 12-17 age group currently eligible for vaccination say they do not think their child’s school should require students to get a COVID-19 vaccine (58%) while four in ten parents (42%) say their school should require this. Views on this question diverge along partisan lines, with two-thirds of parents who identify as Democrats (66%) saying their child’s school should require students to be vaccinated and nearly nine in ten Republican parents (87%) saying it should not. Majorities of White parents and Black parents say their school should not require students to be vaccinated, while Hispanic parents are more evenly divided on this question (51% should, 47% should not).

Not surprisingly, there is a huge divide in opinion of school vaccine mandates among parents by their child’s vaccination status: 75% of parents of children ages 12-17 who have received a COVID-19 vaccine say their child’s school should require vaccination while 83% of parents of unvaccinated children ages 12-17 say they should not.

Parents’ views on schools requiring COVID-19 vaccinations remain divided even when asked how they would feel if the FDA were to grant full approval for the use of a vaccine in children. Among all parents of school-age children (ages 5-17), just under half (45%) say that once a COVID-19 vaccine receives full FDA approval, “schools should require students to be vaccinated for COVID-19 as they do for most other diseases like measles and tuberculosis” while just over half (54%) say schools should not require COVID-19 vaccinations in this scenario.

Similar to the question about their own child’s school, majorities of Democrats, Hispanic parents, and parents of children who have already received a COVID-19 vaccine say schools should require students to receive a COVID-19 vaccine once one is approved by the FDA, while majorities of Republicans, Black parents, White parents, and parents of unvaccinated 12-17 year-olds say they should not.

In general, parents are more supportive of mask mandates in schools than they are of vaccine mandates. Over six in ten parents of children enrolled in school (63%) say their child’s school should require unvaccinated students and staff to wear masks while they’re in school while 36% say they should not. Previous Vaccine Monitor reports have shown that mask-wearing among adults divides largely along partisan lines and the same is true when it comes to opinions about mask mandates in schools. Large majorities of parents who identify as Democrats (88%) and independents (66%) say their child’s school should require masks while most Republican parents (69%) say they should not. In addition, larger shares of Black parents (83%) and Hispanic parents (76%) compared to White parents (54%) support a mask requirement at their child’s school. Among parents of 12-17 year-olds, a large majority (85%) of those whose child has received a COVID-19 vaccine say their school should require unvaccinated students and staff to wear masks while those whose child is unvaccinated are evenly split.

While some parents may be concerned about their child’s risk of exposure to coronavirus at school or in social settings, about four in ten parents of children ages 12-17 (41%) say they don’t know what share of their child’s close friends have been vaccinated for COVID-19 and about half (48%) say the same about their child’s schoolmates. Parents of vaccinated children are much more likely than parents of unvaccinated children to say all or most of their child’s friends (32% vs. 2%) and schoolmates (14% vs. 1%) are vaccinated, while parents of unvaccinated 12-17 year-olds are more likely to say they don’t know the vaccination status of their child’s friends (45% vs. 34%) and schoolmates (55% vs. 38%).

Sources of Information and Information Needs

Throughout efforts to vaccinate adults for COVID-19, the Vaccine Monitor has documented gaps in information about COVID-19 vaccines, including that Black and Hispanic adults and those with lower incomes have been more likely to say they don’t have enough information about vaccine side effects and access.

The latest survey finds that the same is true when it comes to parents’ feelings about information on COVID-19 vaccines for children. While about four in ten parents say they have enough information, over half say they don’t have enough information about the effectiveness (57%) or the potential side effects (60%) of the COVID-19 vaccines in children.

Larger shares of mothers, younger parents, Black and Hispanic parents, those with lower incomes, and parents without a college degree say they don’t have enough information about effectiveness and side effects of vaccines in kids compared to fathers, older parents, White parents, and those with higher incomes and college degrees.

Parents’ Trusted Sources Of Information On COVID-19 Vaccines For Kids

Overall, pediatricians are a top source for trusted information when it comes to COVID-19 vaccines and children. About eight in ten parents overall (78%) say they trust their child’s pediatrician “a great deal” or “a fair amount” to provide reliable information about COVID-19 vaccines for kids. Over six in ten also say they trust the CDC (66%) and their local public health department (62%) at least a fair amount, while a majority of insured parents trust their health insurance company (58%) and over half of working parents trust their employer (53%). Schools and other parents are lower on parents’ list of trusted information sources, with 44% saying they trust their child’s school or daycare for vaccine information and 38% saying the same about other parents they know.

Reflecting partisan divisions in trusted information sources among all adults in previous Vaccine Monitor reports, parents who identify as Republicans are far less likely than those who identify as Democrats to trust most sources of information, with the exception of pediatricians (who are highly trusted by parents across the political spectrum) and other parents (who rank lower as a trusted resource regardless of partisanship).

A key target group for information is parents of unvaccinated children ages 12-17, who are currently eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Among these parents, nearly two-thirds (64%) trust their child’s pediatrician at least a fair amount to provide reliable information about COVID-19 vaccines and children, but fewer than half trust any of the other information sources tested. Notably, among those who say they will “definitely not” vaccinate their child, four in ten (39%) say they trust their child’s pediatrician and fewer than one-third put at least a fair amount of trust in any of the other information sources included in the survey.

Parents’ Vaccine Conversations with Pediatricians And With Their Children

While pediatricians are a top trusted source of information, most parents have not yet discussed COVID-19 vaccinations with their child’s pediatrician. Three in ten parents of children under age 18 say they have talked to their children’s pediatrician about the COVID-19 vaccine, including a somewhat higher share of parents who have children between the ages of 12-17 (35%). Among parents of children in this age range who discussed the vaccine with their child’s pediatrician, 72% (one quarter of all parents of 12-17 year-olds) say the pediatrician recommended that their child get vaccinated for COVID-19.

Parents who say their child’s pediatrician recommended vaccination are about two and half times as likely to say their child has received a COVID-19 vaccine compared to parents who did not talk to a pediatrician or say the pediatrician did not recommend vaccination (75% vs. 31%). However, the extent to which a pediatrician’s recommendation was a deciding factor for these parents is unclear, since parents who are more inclined towards getting their children vaccinated for COVID-19 may have been more likely to initiate these conversations with pediatricians in the first place.

Parents more commonly report discussing the COVID-19 vaccine with their children than with their pediatrician. Among parents of 12-17 year-olds, nearly half (46%) say they have talked with their child about the vaccine “a lot” and another third (32%) say they have discussed it “some.” Parents with college degrees and those who have received the COVID-19 vaccine themselves are more likely to report discussing the vaccine with their adolescent children. In addition, more than six in ten parents of children who have received at least one dose of the vaccine say they have talked with their child “a lot” about the vaccine compared with about a third (35%) of parents of unvaccinated 12-17 year-olds.

About one-third of parents of children ages 12-17 say their child has expressed any concerns to them about getting a COVID-19 vaccine, including one quarter (24%) of parents of vaccinated children and four in ten (41%) parents of unvaccinated children.

Among parents of unvaccinated children ages 12-17, one in eight (12%) say their child has told them that they want to get the vaccine.

When asked to say in their own words the main concern their child has expressed, side effects are at the top of the list, with 29% of parents of children who expressed a concern saying this was their main concern (38% of parents of vaccinated children and 26% of unvaccinated). The second- and third-ranked concerns among parents of unvaccinated children who expressed concerns are not wanting to get the vaccine (16%) and concerns about long-term effects (14%). Among parents of vaccinated children who expressed concerns, 9% say their child was concerned about long-term effects and 8% expressed concerns about the safety of the vaccine.

Methodology

This KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor – Parents and the Pandemic was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The survey was conducted July 15-August 2, 2021 via telephone and online among a nationally representative sample of 1,259 adults who are the parent or guardian of a child under the age of 18 living in their household. The sample includes 351 parents reached through the July 2021 KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor and 908 who were reached online through a probability-based online panel (SSRS Opinion Panel). The Vaccine Monitor respondents were reached through a random digit dial telephone sample of adults ages 18 and older (including interviews from 101 Hispanic parents and 64 non-Hispanic Black parents), living in the United States. Phone numbers used for the telephone component were randomly generated from cell phone and landline sampling frames, with an overlapping frame design, and disproportionate stratification aimed at reaching Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black respondents as well as those living in areas with high rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The sample also included 43 parents by calling back respondents that had previously competed an interview on a KFF poll (n=11) or SSRS omnibus poll (n=32). The comparison sample of non-parents was also drawn from the July 2021 KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. See the July 2021 KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor for further details on the telephone component.

For the online component, invitations were sent to panel members who previously identified as the parent of a child ages 5 to 17. As with the telephone component, Hispanic and Black respondents were oversampled. The SSRS Opinion Panel is a nationally representative probability-based web panel. SSRS Probability Panel members are recruited randomly in one of two ways: (a) Through invitations mailed to respondents randomly sampled from an Address-Based Sample (ABS). ABS respondents are randomly sampled by MSG through the U.S. Postal Service’s Computerized Delivery Sequence (CDS). (b) from a dual-frame random digit dial (RDD) sample, through the SSRS Omnibus survey platform. Sample for the SSRS Omnibus is obtained through Marketing System Groups (MSG).

The combined telephone and online parent samples were weighted to match the sample’s demographics to the national parent population using data from the Census Bureau’s 2019 U.S. American Community Survey (ACS). Weighting parameters included sex, age, education, marital status, child age, and region, within racial/ethnic groups. The weights take into account differences in the probability of selection for each sample type (phone and web). This includes adjustment for the sample design and geographic stratification of the telephone sample, within household probability of selection, and the design of the panel-recruitment procedure.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample of parents is plus or minus 4 percentage points. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request. Sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error and there may be other unmeasured error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF (an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation), the Ford Foundation, and the Molina Family Foundation. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total parents/guardians of children under 18 in household | 1,259 | ± 4 percentage points |

| Parent Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 399 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 372 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Hispanic | 429 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Child Age Groups | ||

| Parents of children under age 5 | 523 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Parents of children ages 5-11 | 674 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Parents of children ages 12-17 | 728 | ± 5 percentage points |

| Comparison sample of non-parents (adults who are not parents or guardians of children under 18) from July 2021 KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor | 1,166 | ± 4 percentage points |

Endnotes

- The survey was conducted July 15 through August 2, with the bulk of interviews being conducted before the most recent data from the CDC indicating the increased risk of the Delta variant to both unvaccinated and vaccinated people. Therefore, the survey may not capture any recent uptick in child vaccinations due to the latest surge in cases. ↩︎

- COVID-19 Vaccines While Pregnant or Breastfeeding (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 29, 2021). Accessed August 9, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/pregnancy.html ↩︎