Rising health care prices have led premiums and deductibles for employer-sponsored coverage to grow faster than wages and general inflation, creating affordability challenges for employers and employees. One proposal to address the high prices paid by private insurers is to cap these prices at a multiple of Medicare rates. States, including Montana and Oregon, have adopted this approach for certain providers under their public employee health plan. In Washington state, the public option in the individual market ties payments to a percent of Medicare rates. This brief considers the potential implications for inpatient admissions and spending of applying a price cap to all private insurance hospital payments in the large employer group market.

In this analysis, we look at in-network payment rates for inpatient hospital stays, other than maternity/newborn admissions, among large employer plans relative to Medicare payment rates. To do so, we analyzed data from the 2018 IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database that includes health claims from a sample of 18 million non-elderly people, representing about 82 million covered lives in large employer plans. Specifically, we examined the share of non-maternity inpatient hospital admissions and associated spending among large employer plans for in-network inpatient admissions paid above various ratios of private-to-Medicare rates. We then focus on 15 common types of admissions (classified using diagnosis related groups, or DRGs), representing more than a quarter of all non-maternity inpatient spending in the large group market (see methods for additional information). This analysis is intended to be illustrative and does not assess potential spillover effects on volume, access, or quality of a policy that caps prices for the privately insured.

Findings

About half of non-maternity inpatient hospital admissions in the large group market would be affected by a cap on prices set to 150% of Medicare rates. Based on our analysis, 52% of inpatient admissions were paid above 150% of Medicare rates, meaning just over half of all admissions would be affected by a cap on payments set at this level. Moving from 150% to 200% of Medicare rates, the share drops to just about one-third of admissions (32%). If the payment rate was capped at 300% of Medicare rates, 13% of admissions would be affected (Figure 1).

A cap set at a multiple of Medicare rates would affect a sizeable amount of inpatient spending in the large group market, even if set at 300% of Medicare rates. Just over one-third of non-maternity inpatient spending in the large group market is for spending associated with the portion of prices above 150% of Medicare rates. In other words, if no admission was paid more than 150% of Medicare, all else equal, spending would be 36% lower. Capping prices at 300% of Medicare rates would affect 13% of spending covered by employer plans (Figure 1).

Across 15 common types of admissions, the share of in-network admissions paid above 150% of Medicare varies substantially. For example, among patients covered by large group plans, 71% of admissions for hip and knee joint replacements (DRG 470) are paid more than 150% of Medicare rates, whereas only 15% of admissions for psychosis (DRG 885) are paid above 150% of Medicare rates.

Among these same 15 DRGs, between 3% and 19% of large group plan admissions have payments above 300% of the Medicare rates. For 6 of these 15 DRGs, at least 15% of inpatient stays in the large group market are paid above 300% of Medicare rates (DRG 247, DRG 460, DRG 219, DRG 025, DRG 871 and DRG 853). Figure 2 shows the share of admissions paid within different ranges of multiples of Medicare rates.

In other words, because the distribution of current prices varies widely across DRGS, the choice of where to set a cap would matter more for some types of admissions than others (Figure 2). It would also have different affects across individual hospitals depending on their current prices and distribution of admissions.

The average price for an in-network large group admission would fall more for admissions that currently have higher prices relative to Medicare. To illustrate how a cap set at a percent of Medicare rates might work, we repriced admissions currently paid above each multiple of the Medicare payment rate and recalculated the average price for the DRG in the large employer market. If a cap is set at 200% of Medicare rates, we assumed all large group admissions that are currently paid a at a higher rate would be paid the lower price of 200% of Medicare. For example, for hip and knee replacements, the average price paid by large employer plans would decrease from $30,506 to $25,366. The decrease would be smaller for psychoses under the same scenario, falling from $9,425 to $8,420 (Figure 3). In these illustrative calculations, we made no assumptions about spillover effects on the volume of admissions or prices paid underneath the cap. In practice, volume could increase to compensate for lower average prices with a cap, and the price for admissions below the cap could rise for the same reason.

Conclusions

High and rising health care costs, driven by high and rising prices, and exacerbated by increasing provider consolidation, are contributing to affordability challenges for people with employer-sponsored coverage. To counteract these effects, some have considered capping prices as a multiple of Medicare rates, following the lead of states, such as Montana, that have adopted this policy for its state employees’ health insurance plan.

Our analysis finds that a cap of 150% of Medicare rates would affect 52% of in-network admissions and 36% of in-network spending, while a cap of 300% of Medicare rates would affect 13% of in-network admissions and 13% of in-network spending, with variation across types of admissions. A lower cap would affect a larger share of admissions than of spending, because at lower levels more admissions are currently paid just above the potential cap. A cap on prices could potentially apply to both in- and out-of-network services, as has been proposed in other contexts. Our analysis examines in-network admissions, which account for the vast majority of spending in the group market. Therefore, our findings are illustrative of the range of admissions that could be affected and would not be substantially different if we included out-of-network admissions.

A cap on prices paid in the group market could be disruptive depending on the level at which the cap is set and the number of services to which it applies. At the same time, if a cap achieved meaningful savings, it could make health care more affordable - tradeoffs that warrant careful attention. In our analysis, we do not attempt to model any changes that may follow from a cap on prices, such as an increase in volume or an increase in prices for admissions that are below the cap. However, in Montana, capping prices at a multiple of Medicare rates resulted in net savings and utilization did not increase. There could also be effects on networks. In Washington state, some hospitals are not participating in the network for the public option in the individual market because the cap on prices of 160% of Medicare is too low. While it is unlikely that hospitals could forgo the large group market entirely, it is possible that some hospitals would choose to contract with fewer plans, creating access concerns.

While this analysis does not consider the potential impact on quality, it is possible that some high-priced inpatient admissions are of high quality and restricting prices could have a negative impact in those cases. There is some evidence this may be the case in unconcentrated (more competitive) markets. Additionally, a recent report by the Congressional Budget Office notes a correlation between prices and quality, though states there is not evidence of causality and it is not clear whether higher prices lead to higher quality or vice versa.

Capping the prices employer-sponsored plans pay for inpatient admissions would likely reduce hospital revenue. The magnitude of the impact would depend on the level of the cap, and whether volume changed in response. While affected providers could respond by operating more efficiently, it is also possible that decreases in revenue could lead to lower pay for hospital staff, fewer capital investments, and efforts to shift admissions away from payers who pay lower prices. These changes could be especially unpalatable during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has prompted billions of dollars in federal funding to help support and stabilize hospital finances.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Methods

To calculate private insurance payment rates, we analyzed a sample of medical claims obtained from the 2018 IBM Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. We only included claims for people under the age of 65. This analysis used claims for 18 million people representing about 22% of the 82 million people in the large group market in 2018. Weights were applied to match counts in the Current Population Survey for enrollees at firms of a thousand or more workers by sex, age, and state. Weights were trimmed at eight times the interquartile range. We exclude admissions accounting for 12% of total spending in Marketscan, namely DRGs related to childbirth. When selecting common DRGs, we did not include DRGS with fewer than 800 observations, regardless of the amount of spending attributed to those cases.

Averages represent the amounts paid to the hospitals for an admission. Across all the DRGs, hospital spending represented about 87% of the total cost of the admission. Costs include both amounts paid by enrollees in the form of cost sharing and spending by the plan. Hospital costs are trimmed to exclude the highest 0.5% of hospital costs within a DRG and admissions below 5% of the median. This is intended to exclude admissions in which the claims do not capture all the spending on the admission. These data reflect cost sharing incurred under the benefit plan, but do not include balance-billing payments that beneficiaries may make to health care providers for out-of-network services delivered during the admission or out-of-pocket payments for non-covered services. Only admissions with in-network room and board charges are included. Limiting to in-network admissions does not qualitatively affect our findings. In-network spending is about 90% of total spending after trimming outliers.

To calculate Medicare payment rates, we analyzed average payments to hospitals for admissions identified through the DRG, as reported in Inpatient Charge Data FY 2018. According to CMS documentation, the DRG reimbursements are "the average total payments to all providers for the DRG including the MS-DRG amount, teaching, disproportionate share, capital, and outlier payments for all cases. Also included in average total payments are co-payment and deductible amounts that the patient is responsible for and any additional payments by third parties for coordination of benefits." These files are prepared by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) using Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) data. For more information see: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Downloads/Inpatient_Methodology.pdf.

IBM assigns a DRG to each admission using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Grouper 37. This method selects a DRG for the admission based on the diagnosis and procedures a patient received during the case. The total payments to hospitals in the Marketscan data reflect the payments made to the hospitals. Some variation in the payment rates of admissions is accounted for by differences in the intensity or types of services that a patient receives, and not differences in the rates paid for those services. The rates Medicare uses to reimburse DRGs are designed to account for this variation in the intensity of cases and services. This analysis compares the average of DRG payment rates in Medicare to admissions in Marketscan. CMS suppresses DRGs with low counts; in order to use the most DRGs, we use national averages rather than the price in particular States or MSAs. Therefore, this analysis does not account for regional variation in Medicare reimbursement.

In Medicare, hospital admissions are reimbursed based on DRGs that reflects a patient’s clinical conditions and treatment. In contrast, private insurers pay for hospital admissions using different approaches that may vary with the procedures performed during the stay, including per diem payments, discounted fee-for-service payments, DRGs or other combinations of payments and performance incentives. Therefore, the variation in payment within DRG among large group plans, may reflect both variation in the intensity of services and the length of stay, as well as the prices being paid for those services.

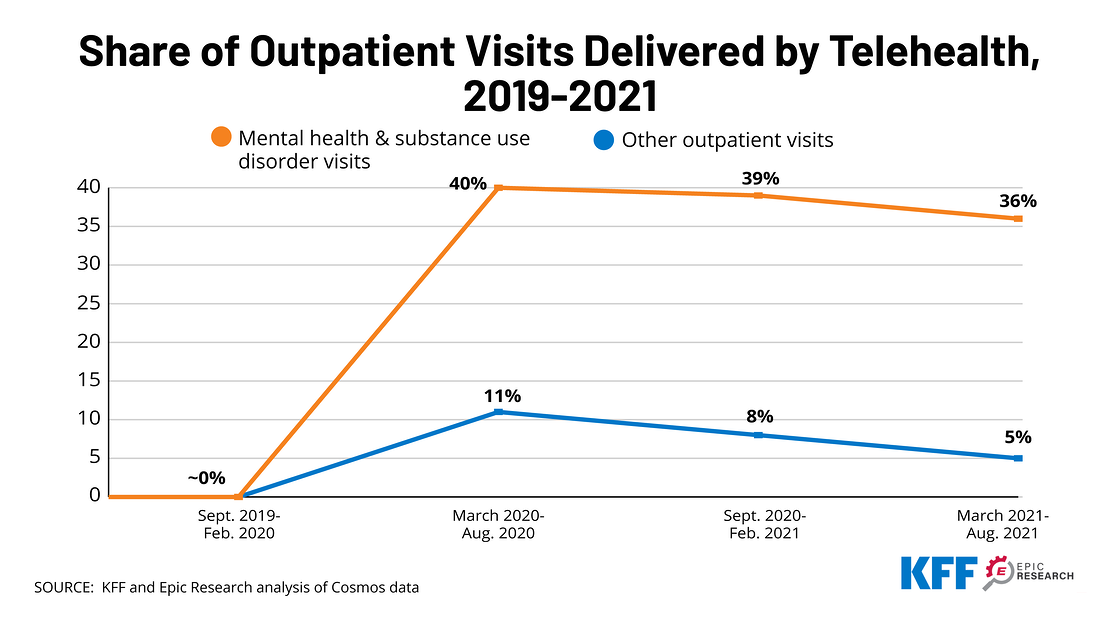

A new analysis from KFF and Epic Research finds that telehealth visits for outpatient mental health and substance use services went from virtually zero percent in 2019 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic to a peak of 40% in mid-2020 – and continued to account for more than a third (36%) of such visits in the six months ending in August 2021.

A new analysis from KFF and Epic Research finds that telehealth visits for outpatient mental health and substance use services went from virtually zero percent in 2019 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic to a peak of 40% in mid-2020 – and continued to account for more than a third (36%) of such visits in the six months ending in August 2021.